5

The Written Evaluation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain why written performance appraisals are so important.

• Explain why writing performance appraisals are a useful tool for maximizing effective employer-employee relations.

• Describe the importance of establishing a format.

• Identify key writing dos and don’ts.

• Select appropriate language.

Very good managers often write extremely bad performance appraisals. Here is an example, taken from a written review prepared by Rob who is an intelligent, well-respected manager working for a Fortune 500 company. When asked how he would rate his review, he responded, “Overall, I’d say it’s very good: succinct and to the point.”

Here is Rob’s review in its entirety. See what you think:

Job Title: Marketing Assistant

The brevity of Rob’s words, poor language selection, reference to recent events, and failure to establish a format all reflect his lack of understanding as to why written performance appraisals are important, as well as what skills are required to perform this critical task successfully.

Not surprisingly, Rob confided that he is uncomfortable writing performance appraisals, although he could not articulate why. “I just don’t like doing them,” was his response when asked. He added that he does not have an aversion to writing as such. He can write memos or reports of any type or length; he just dislikes writing employee reviews, whether positive or negative.

Rob is not alone in his feelings about writing employee reviews. Many otherwise effective managers are uneasy about writing performance appraisals. Why this is the case will be one of the topics for discussion in this chapter. In addition, we will review important writing dos and don’ts, the importance of establishing a format, as well as appropriate language selection.

If you are like Rob, perhaps by the end of this chapter, you will view the process of writing performance appraisals as less of a chore and more as a useful tool in maximizing employer-employee relations.

WHY WRITTEN PERFORMANCE APPRAISALS ARE IMPORTANT

Effectively written performance appraisals leave little room for misinterpretation by either the employee or the manager. When the written word works in concert with what the appraising manager says during the face-to-face meeting, the nature and level of an employee’s performance is reinforced.

Written appraisals become a permanent record attesting to an employee’s performance for a specified period of time. This record is often used to:

• Justify salary increases

• Support transfers, promotions, or other changes in job status

• Support disciplinary action, up to and including termination

Let’s examine each of these uses more closely.

Justify Salary Increases

It is not uncommon for organizations to link salary increases with annual performance reviews. Furthermore, pay raises are usually driven by merit. Hence, employees receiving high performance ratings are going to anticipate increases in pay commensurate with those ratings.

Let’s look at how this might work. Donna is the human resources representative responsible for reviewing her organization’s performance appraisals once they have been completed and submitted by managers. Her job includes looking for consistency between comments and ratings for each category, as well as consistency between the overall rating/comments and all those ratings/comments preceding it. Once a manager has met with his or employee, and the employee has signed the review (indicating understanding of its contents and not necessarily agreement), Donna places her salary increase chart along side the completed review. Each of her company’s four-term rating’s reflects a corresponding percentage salary increase: Extraordinary = 5–5.5%, Excellent = 4–4.5%, Good = a maximum of 3%, and Poor = 0%. (Note: if an employee receives a “poor” rating in multiple categories and an overall rating of “poor,” one has to ask why he or she is still on payroll.)

If Donna finds consistency throughout each of the appraisal categories, culminating in an overall evaluation that supports the preceding ratings, her job is easy. If, however, there is a lack of uniformity between categories and the final rating seems out of kilter, she then needs to confer with the manager. Generally, either the individual evaluations or the final rating is inaccurate. Sometimes, however, there is one category that the manager feels should weigh more heavily than all the others; hence, the rating for that competency skews the other scores. This is acceptable if the category is job-specific, HR agrees, and most importantly, if the employee is aware of the additional emphasis on this task of area of responsibility.

Salary-related problems arise when there is a lack of consistency between ratings and pay raises. One of the simplest ways to avoid this inconsistency is for managers to submit written reviews to HR for confirmation of consistency prior to meeting with employees. The ideal solution is to separate salary reviews from performance appraisals. Employees are more likely to focus on the manager’s observations and not translate ratings into dollars.

Support Changes in Job Status

Job posting is commonplace in many workplaces, offering employees opportunities for both advancement and lateral transfers to other departments. Performance appraisals act as critical documents in this process, often serving as the main basis for supporting or denying changes in employee job status.

Let’s consider some examples:

• Ralph applies for a promotion to a job requiring critical thinking and quick decisions. His most recent performance appraisal provides several examples of instances in which he has made decisions resulting in increased revenues for the company.

• Joseph likes his work, but finds it difficult to get along with his boss. He applies for a transfer to another department where he will perform essentially the same function. The manager of the department with the opening looks at his last performance appraisal and reads the following comment in the category, independence: “Joseph is too independent; he likes to work without a great deal of supervision.”

The manager realizes that this was intended to be a criticism, but instead views it in a positive manner: she wants someone who can work independently. Perhaps the appraiser’s comment is part of the problem with the working relationship between himself and Joseph, causing the latter to apply for a transfer.

• Ali’s boss is promoted, leaving his job vacant. The person making the replacement selection is the vice president to whom Ali’s boss reported: someone with whom she has had little direct contact. Ali applies, believing she can do the work. Unfortunately, her last review tells a different story: she is described as “having difficulty adhering to company policy” and as being “excessively argumentative.” There are no examples to support either statement. The vice president can now choose to accept what the performance appraisal says without seeking clarification (not recommended), or contact the former incumbent, asking for specific examples. He should also meet with Ali and form his own opinion, mostly by asking competency-based, open-ended, hypothetical, probing, and close-ended questions. (These types of questions will be discussed in Chapter 6.)

Support Disciplinary Action

One of the most important rules of performance appraisals is that nothing said in writing or during an appraisal meeting should come as a surprise to employees. If managers have addressed disciplinary matters throughout the year via coaching and counseling sessions, then a recap of these instances during the formal review is appropriate. If, however, the manager did not do his or her job as a coach and counselor at the time of an occurrence calling for progressive discipline, then it is inappropriate to record it on the appraisal form or discuss it during the face-to-face meeting for the first time.

Let’s continue with the logical progression of what might happen if matters calling for discipline are addressed in a timely fashion and subsequently recorded on the performance appraisal form. Should the employee correct the documented behavior, this should be acknowledged. If, however, the behavior continues or escalates, the written performance appraisal becomes an important point of reference. Consider this excerpt from a written review:

Category: Reliability: The extent to which an employee can be relied upon to complete a given task and follow-up as needed

Rating. Poor

Comment: Despite repeated discussions concerning her failure to meet deadlines in a timely manner (see attached memos reflecting coaching and counseling sessions), Danielle continues to consistently turn her work in late. She has been given two verbal warnings (see attached documentation) and understands, as indicated by her signature, that the continuation of this behavior will lead to further disciplinary action up to and including termination.

If Danielle’s issue with reliability were not addressed in the written review, despite documentation in her file, any future steps toward disciplinary action could be adversely impacted. This would be especially true if the appraising manager rated her using terms that contradicted coaching and counseling documentation on file.

Does your organization link salary increases with performance appraisals? _____ yes _____ no

If it does, what happens if there is inconsistency between comments and ratings for each category, and/or inconsistency between the overall rating/comments and all those ratings/comments preceding it? Specifically, what is the impact on an employee’s salary?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Does your organization offer employees job change opportunities via job posting? _____ yes _____ no

If it does, what is the relationship between an employee being considered for a job change and his or her prior performance appraisal?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Does your organization have a progressive disciplinary system? _____ yes _____ no

If it does, what is the relationship between an employee who has been disciplined and his or her upcoming performance appraisal?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

If managers were made aware that performance appraisals could be used to justify salary increases, support changes in job status, and back up disciplinary action, do you think they would be less resistant to writing them? _____ yes _____ no. Support your answer.

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

WHY MANAGERS DISLIKE WRITING PERFORMANCE APPRAISALS

Despite the fact that written performance appraisals can be used to justify salary increases, support changes in job status, and back up disciplinary action, managers still resist. They are quick to offer many reasons for this, including the following:

1. “There’s too much to say; I can’t possibly fit everything in the space provided.”

2. “I have nothing to say; besides, the employee’s performance speaks for itself.”

3. “I don’t write well; after all, I’m a manager—not a writer.”

4. “I have a problem with praising people; besides I don’t want to embarrass an employee by complimenting him or her too much.”

5. “I have a problem with criticizing people; I know I hate being criticized.”

6. “It’s a thankless task; HR always gets on my case about not doing it right. I’ve given up trying to please them.”

7. “I’m afraid my words will come back to haunt me. What if I’m wrong? Saying something face-to-face is all right—but committing yourself to paper can be dangerous.”

8. “It takes too long; who has that kind of time?”

9. “It’s hard work, especially when you have to criticize someone.”

10. “All employees really care about is how much of a raise they’re getting, so why bother?”

In addition to these reasons, managers have reportedly expressed concern about what could happen if they write what they really think. Fill in the blank of the following statement with any of the terms provided to see what many managers have said they are worried about:

If I write what I really think, employees will _______________.

• Argue with me

• Bad-mouth me

• Be angry with me

• Become defensive

• Behave disruptively

• Cry

• Lie

• Report me

Think About It…

Think About It…

Of the ten reasons cited for disliking writing performance appraisals, I can relate to (write as many as apply):

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

I have reasons of my own for disliking writing performance appraisals, including:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

I cannot relate to any of this; I like writing performance appraisals because:

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

• Turn others against me

• Walk out

• Yell

VIEWING WRITTEN PERFORMANCE APPRAISALS AS A USEFUL TOOL

Managers can learn to view writing performance appraisals as less of a chore and more as a useful tool in maximizing effective employer-employee relations by honestly answering three questions. Let’s examine those three questions via my experience.

I was conducting a performance appraisal seminar for a group of managers whom I knew would resist the idea of writing reviews. After talking briefly about the benefits of written appraisals, it was evident that I was not making any headway. This audience was simply not buying any of my persuasive talk, so I decided on a different approach. Instead of telling them why written performance appraisals were so beneficial, I asked three questions:

Question #1: “Who likes writing performance appraisals?” I queried. Not surprisingly, no one raised his or her hand.

Question #2: “Who thinks written performance appraisals are important?” Again, I was not surprised to see that this time everyone’s hand went up. I smiled and summarized, “You don’t like writing them but agree that they’re important; that’s interesting.”

Question #3: “Who thinks someone else should write the appraisals then?” The room was initially quiet; then some of the managers started murmuring to one another. I asked someone to volunteer what he or she was thinking. “I don’t like the idea of someone else writing a review for one of my employees—I’m the only one who really knows what they can and can’t do,” said one manager. Others nodded in agreement. Another said, “I’d like to tell someone what I think and have him or her write it.” “What kind of sense does that make?” challenged a colleague. “If you’re going to take the time to talk about it, just write it down!”

This exchange continued for about ten minutes, at which point I asked volunteers to summarize what they had concluded. Without hesitation, here’s what they collectively said: (Note: the word “it” refers to the written performance appraisal.) (1) Managers should just do it! (2) Managers should learn how to do it right! (3) If managers learn how to do it, and do it right, it’s a win-win situation for everyone! I could not have agreed more.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ESTABLISHING A FORMAT

The success of any performance appraisal system is rooted in consistency and uniformity; that is, all managers following the same format. This concept extends to the written review. Employees need to know that they are being evaluated according to the same standards as everyone else, that their salary increases are based on the same factors, and that ratings used to gauge the extent of their accomplishments are the same ones used to evaluate the accomplishments of their coworkers.

A Seven-Step Format

The following seven-step format for written performance appraisals (Exhibit 5–1) is simple, yet highly effective when it comes to ensuring consistency and uniformity. The approach is applicable to virtually every workplace, is appropriate for all employee classifications, and works with any type of appraisal form, regardless of the categories included. Optimum results will be achieved if self-evaluations by employees are factored in as well.

Step 1: Overview. Provide a two-to-three sentence summary of the employee’s performance since his or her last review or date of hire. Avoid referencing specific incidences. Here’s an example:

Since the date of her last annual review, Veronica has continued to exhibit an in-depth understanding of her job. She consistently performs her responsibilities in an exemplary fashion, serving as a role model for new hires.

Step 2: Strengths. Identify employee strengths, supported by specific examples. Try to highlight examples reflecting a variety of assignments performed under varying circumstances throughout the year. Try also to reflect different strengths, especially those reflecting growth and development since the time of hire or the last review.

Step 3: Areas Requiring Improvement. Identify areas in which the employee requires improvement, supported by specific examples. Be careful not to preface any statements with terminology like, “I think…” or “In my opinion….”

Think About It…

Think About It…

Can you think of any reason as to why a consistent and uniform written performance appraisal format would not work in your organization?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

What could be done to eliminate this reason from interfering with a uniform and consistent written performance appraisal format in your organization?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

xhibit 5–1

xhibit 5–1

Seven-Step Format for Written Performance Appraisals

Step 1: Overview

Provide a summary of the employee’s performance since his or her last review or date of hire.

Step 2: Strengths

Identify employee strengths, supported by specific examples.

Step 3: Areas Requiring Improvement

Identify areas in which the employee requires improvement, supported by specific examples.

Step 4: Meeting Previously Agreed-Upon Goals

Review the employee’s success in meeting specific goals that were mutually agreed-upon at the time of the last review or time of hire.

Step 5: Setting New Goals

Identify new, mutually agreed-upon goals for the employee to achieve accompanied by a timeline.

Step 6: Career Development

Together, identify how the employee will achieve personal and professional development.

Step 7: Employee Feedback

Solicit the employee’s written comments on the performance appraisal form accompanied by his or her signature.

Areas requiring improvement should be job-specific, as well as tangible or quantitative.

Citing examples of areas requiring improvement can lend itself to a discussion of setting goals (Step 5).

Step 4: Meeting Previously Agreed-Upon Goals. Review the employee’s success in meeting specific goals that were mutually agreed-upon at the time of the last review or time of hire. Cite the goal; then specify exactly what the employee did or did not do toward meeting that goal. Avoid general terms, such as “Richard did a great job meeting all his goals from last year!” or “Jen needs to keep working hard so she can meet the goals she set last year.”

Step 5: Setting New Goals. Identify mutually agreed-upon goals for the employee to accomplish by the date of his or her next appraisal. Goals should be clear, measurable, time-tied, and focused on results. For example, “Launch four new testing programs in the coming fiscal year” is clear, measurable, time-tied, and focuses on results.

Develop a timeline with interim meetings set to review progress and identify any problems encountered by the employee as he or she strives to meet these goals. New goals may also include a carry-over of goals from the last meeting. Revisit and rework them as needed, ensuring that they are achievable and desirable from the employee’s perspective.

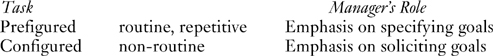

While goals should be mutually agreed-upon, managers play a greater role in specifying goals for work that is primarily prefigured; that is, routine, repetitive tasks. Managers generally solicit goals from the employee for work that is primarily configured; that is, non-routine tasks. Hence:

Think About It…

Think About It…

Do the managers in your organization consistently and uniformly practice the seven-step format for written performance appraisals?

If you answered “no” for any of the steps, what do you think it would take to help managers consistently and uniformly practice the seven-step format for written performance appraisals?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Step 6: Career Development. Managers should encourage employees to discuss career goals and aspirations. Together, they can then identify how the employee will achieve personal and professional development, for example, through seminars, training, and schooling. These goals should be linked, as much as possible, with organizational goals.

Step 7: Employee Feedback. Solicit employee signatures and written comments on the performance appraisal form. As stated earlier, their signature signifies understanding of the contents and not necessarily agreement. Their comments, while unlikely to result in a changed evaluation, can serve to enhance future employer-employee relations.

WRITING GUIDELINES

Conveying the right tone and using an appropriate writing style will set the stage for a productive face-to-face meeting. Simply stated, your tone should be direct, factual, and positive; your style should be moderate to formal, with limited jargon and no clichés.

Writing Dos

Here are some additional guidelines to help managers write effective performance reviews:

1. Do begin planning the written performance appraisal approximately one month prior to the due date, jotting down thoughts as they occur to you.

2. Do write the review and then put it away for a few days. Return to it and read it from multiple perspectives, including your own, that of the employee, and that of human resources.

3. Do use the employee’s position description as the foundation for your written review, striving to link each comment with specific job duties and responsibilities.

4. Do support each rating with multiple examples and facts.

5. Do be prepared to discuss supporting examples.

6. Do try to present a balanced picture of strengths and areas requiring improvement.

7. Do look at an employee’s entire performance record since his or her last review, date of hire, or date of most recent job change—whichever applies.

8. Do consider the employee’s self-evaluation, as well as evaluations solicited from others, such as colleagues and clients.

Think About It…

Think About It…

When managers in your organization write performance appraisals, do they know to

… begin planning the written performance appraisal approximately one month prior to the due date? _____ yes _____ no

… write the review and then put it away for a few days; then reread it from multiple perspectives? _____ yes _____ no

… use the employee’s job description as the foundation for their written review? _____ yes _____ no

… support each rating with multiple examples and facts? _____ yes _____ no

… present a balanced picture of strengths and areas requiring improvement? ____ yes ____ no

… look at an employee’s entire performance record? _____ yes _____ no

… consider the employee’s self-evaluation? _____ yes _____ no

… consider the evaluations of others? _____ yes _____ no

… use language that clearly conveys what is expected and acceptable? _____ yes _____ no

… strive for consistency between reviews and salary recommendations? _____ yes _____ no

… evaluate performance, not personality? _____ yes _____ no

… strive to be honest? _____ yes _____ no

Pat yourself and your organization on the back for all the questions you answered with a “yes”! Then strive to convert the “no’s” into “yes’s,” perhaps via training workshops on effective performance appraisal writing for managers.

9. Do ensure that the written review clearly conveys what is expected of the employee, as well as what is acceptable and what is not.

10. Do strive for consistency between your evaluation and salary increase recommendations.

11. Do evaluate performance, and not personality.

12. Do be honest.

Writing Don’ts

1. Don’t allow superior performance in certain categories to influence your ratings in other categories. For example, an employee’s job knowledge may be outstanding, but it does not make up for the fact that he or she is unreliable.

2. Don’t make up strengths or areas requiring improvement that do not exist for the sake of creating a balanced picture.

3. Don’t be influenced by first impressions or past performance to the extent that you overlook legitimate performance-related issues.

4. Don’t use the same words to evaluate all employees.

5. Don’t use absolutes, such as “always” and “never.”

6. Don’t downplay poor performance because you are concerned about hurting an employee’s feelings or worried that an employee will no longer like you after reading his or her review.

7. Don’t introduce anything new: remember, nothing that is said or written during the performance appraisal process should come as a surprise to an employee.

8. Don’t play it safe by selecting the middle evaluation term for all performance factors.

Think About It…

Think About It…

Of the all the writing “don’ts” identified, which are the three you believe are practiced most frequently by managers in your organization? Why do you think this is so?

_____ Allowing superior performance in certain categories to influence ratings in other categories.

_____ Making up strengths or areas requiring improvement that do not exist.

_____ Being excessively influenced by first impressions or past performance.

_____ Using the same words to evaluate all employees.

_____ Using absolute terminology.

_____ Downplaying poor performance out of concern for the employee’s feelings or worry that the manager will fall out of favor with the employee.

_____ Introducing something new.

_____ Playing it safe by selecting the middle evaluation term.

_____ Being affected by the “recency factor.”

_____ Being swayed by the “similarity factor.”

_____ Being influenced by the “sympathy factor.”

_____ Saying anything that cannot be supported by facts.

9. Don’t be affected by the “recency factor”; that is, a tendency to be substantially influenced by recent job performance—whether positive or negative.

10. Don’t be swayed by the “similarity factor”; that is, a tendency to dole out higher ratings to those whose views or characteristics are similar to your own.

11. Don’t be influenced by the “sympathy factor”; that is, an inclination to overlook performance issues because of personal issues.

12. Don’t say anything that cannot be supported by facts.

LANGUAGE SELECTION

Language selected for written performance appraisals should be objective. Objective words are impartial and likely to be interpreted similarly by most people. On the other hand, subjective language reflects one’s personal opinion, may be subject to interpretation, and fails to communicate relevant, concrete information. An example of an objective statement concerning “job knowledge” would be, “Jill possesses the practical and technical knowledge required for this job.” An example of a subjective statement would be, “I think Jill has what it takes to do this job!”

Subjective language that is supported by specific, job-related facts can be made objective. For example, consider the subjective statement, “I think John is very productive.” It can be made objective in the following way: “I think John is very productive in that he frequently has his station ready on time.”

Objective language can be used to evaluate outstanding, average, and marginal employees. Here are three examples of objective comments appearing on a performance appraisal form for the category “Job Knowledge:”

Outstanding Employee: Carolyn demonstrates an in-depth understanding of both the practical and technical knowledge needed to perform her job, far exceeding that which is required. She is also willing to impart that knowledge to coworkers having difficulty understanding certain aspects of their jobs. (Note: specific examples would elaborate on instances in which Carolyn has helped coworkers.)

Average Employee: Clarke demonstrates a sound understanding of the practical knowledge required for his job, but resists help with certain technical aspects in which he is not as well versed. This, in turn, occasionally prevents him from completing his work in a timely fashion. (Note: specific examples would elaborate on instances in which Clarke’s diminished technical knowledge has prevented him from completing his work on time.)

Marginal Employee: Lana possesses a marginally acceptable level of knowledge with which to perform her job, with her technical knowledge slightly outweighing her practical knowledge. This is not due to a lack of effort on her part; she simply does not seem to grasp the fundamentals required to perform her work. This has resulted in other employees having to perform some of her tasks, producing a growing morale problem.

(Note: specific examples would elaborate on examples of Lana’s effort to become more knowledgeable about her job, as well as to describe specific instances in which Lana’s limited job knowledge has resulted in other employees having to do her work in addition to their own.)

Exercise: Objective and Subjective Language

Exercise: Objective and Subjective Language

Look at the following words in relation to the eleven performance appraisal factors in the left-hand column. If you believe the statement is objective, put a check mark in the “Objective or Subjective” column. If you feel the statement is subjective, reword it so that it is objective. (Note: indicating that a statement is objective does not mean it can or should stand alone; the addition of supporting facts or examples is presumed.)

__________________________________________________________________________

HINTS, SUGGESTIONS, AND SOME ANSWERS

Written performance appraisals are important for several reasons. When effectively prepared, they leave little room for misinterpretation by either the employee or the manager. In addition, when the written word works in concert with what the appraising manager says during the face-to-face meeting, the nature and level of an employee’s performance is reinforced.

Written appraisals also become a permanent record attesting to an employee’s performance for a specified period of time. This record is often used to justify salary increases, support transfers, promotions, or other changes in job status, as well as support disciplinary action, up to and including termination.

Many managers resist writing performance appraisals, despite their many uses. They cite numerous reasons for this resistance, including concern that what they write will come back to haunt them, apprehension connected with criticizing others, and worry over not being able to write well. Managers can learn to view writing performance appraisals as less of a chore and more as a useful tool in maximizing effective employer-employee relations by acknowledging the fact that they best know what employees can and cannot do.

The success of any performance appraisal system is rooted in consistency and uniformity; that is, all managers following the same format. This concept extends to the written review. Employees need to know that they are being evaluated according to the same standards as everyone else, that their salary increases are based on the same factors, and that ratings used to gauge the extent of their accomplishments are the same used to evaluate the accomplishment of their coworkers. A simple, yet highly effective seven-step format helps managers achieve optimum results.

Conveying a certain tone and using a particular style will set the stage for a maximally productive face-to-face meeting. Simply stated, your tone should be direct and positive, and your style moderate to formal.

Language selected for written performance appraisals should be factual, job-related, specific, and objective. Objective words are impartial and likely to be interpreted similarly by most people. On the other hand, subjective language reflects one’s personal opinion, may be subject to interpretation, and fails to communicate relevant, concrete information. Subjective language that is supported by specific, job-related facts can be made objective.

1. The purpose of the important, tone-setting, first step in the seven-step appraisal-writing format is to:

1. (b)

(a) identify employee strengths and areas requiring improvement, supported by specific examples.

(b) provide a summary of the employee’s performance since his or her last review or date of hire.

(c) determine how successful the employee has been in meeting mutually agreed-upon goals at the time of the last review or time of hire.

(d) ascertain agreement from the employee that he or she will ultimately provide support for the contents of the written review via his or her signature.

2. Managers can turn performance appraisal writing into a win-win situation for all concerned if they:

2. (c)

(a) let human resources write the reviews.

(b) rely on employee self-appraisals.

(c) accept the fact that written reviews are useful tools.

(d) refrain from saying anything negative.

3. Objective language is used to evaluate:

3. (a)

(a) outstanding, average, and marginal employees.

(b) average employees only.

(c) marginal employees only.

(d) outstanding employees only.

4. Written performance appraisals become a permanent record attesting to an employee’s performance for a specified period of time. This record is often used to justify salary increases, support disciplinary action, and:

4. (a)

(a) support changes in job status.

(b) make the manager look good.

(c) justify the need for additional human resources.

(d) support what is said during the face-to-face meeting.

5. The “similarity factor” refers to:

5. (d)

(a) the relationship between an employee’s review and the manager’s recommendation for a salary increase.

(b) the correlation between what a manager writes and what he or she says during the appraisal meeting.

(c) the like rating of several employees working in a similar capacity.

(d) a tendency to dole out higher ratings to those whose views or characteristics are similar to one’s own.