CHAPTER 6

A Quota Quandary: Setting Equitable and Profitable Sales Goals

I PULLED INTO THE PARKING LOT of an office building in suburban Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C. It was a brisk autumn day but the environment inside the offices was anything but cool. Over the course of the next three hours, I sat with Jim, a senior sales executive of a leading health insurance company, locked down in his office discussing the quota process and how “unfair” it was to the sales organization. As he ignited yet another cigarette in an already smoke-filled room, I mused about the contradiction between his habit and his line of business and listened as he talked about “the number,” “the quota,” and “the goal.” His business unit had done well this year, and some of his reps had done extremely well. As we worked to set quotas for the next fiscal year, he talked about how he and his team were being penalized for their great performance. “You know, Mark,” he said, “we knock it out of the park and what kind of reward do we get? A bigger quota next year.” I had heard this before in more than a few organizations.

My next stop was a quick flight away in a town outside Boston called Salem, where I visited with another sales executive in the same health insurance company. I took a rental car from Logan Airport, drove carefully through the ancient streets, and found a parking spot near the office. I had a few minutes before my meeting, so I took the scenic walk through the old burial ground and the Salem Witch Trials Memorial. As I read the about the horrific ordeals that took place in Salem in 1692, I thought of Jim’s quota quandary. Were these sales executives being figuratively crushed to death by the unbearable weight of the quotas handed down from the corporate judges?

At the office, there was another conversation about how the team had a great year and how the quotas were simply unrealistic. Again, the same word pattern emerged about “the number” and “the quota.” Following this meeting, I continued these conversations with others throughout the organization. It became apparent that the issue was not about the number; it was about what went behind the number. It was about the quota-setting approach, the assumptions, the top-down nature of the process, and the team’s utter lack of input and confidence in how their numbers were set. For this organization, the problem wasn’t as much a quota issue as it was a people issue and a trust and confidence issue.

In the end, we flipped the quota-setting process upside down and changed the conversations the organization had. We focused not on what the number was but on how the number was set and how people could be involved and own the process. The pressure shifted away from the number and onto the quality of the conversations. The resulting quota number became the product of the combined efforts of the sales team, senior leadership, sales operations, and finance. Did the sales teams get a dramatically different quota for the new year than they would have gotten under the old approach? In many cases, yes; in some cases, no. But the fact that the team owned the quota and knew where it came from got them down to business and able to put their energy into the market rather than into attacking one another. And ultimately, the company had another strong year, despite the prior belief that the goals were insurmountable.

Quotas are the allocation of the company’s goal to the business units, sales teams, and finally the front-line sales organization. At the front line, the quota represents each rep’s ownership of her piece of the revenue plan or profit plan. While quotas arguably may not be part of sales compensation, without them, most sales compensation plans won’t work. A team can painstakingly work through each step of the sales compensation evaluation and design process and create a great plan that can be neutralized by poor quota setting. Given the choice, I’d rather have a good sales compensation design and a good quota-setting process than a phenomenal plan and a bad quota-setting process. “If I see imbalance in compensation, 95 percent of the time it’s because of bad quota setting,” says Paul Johnson, vice president of sales and marketing for Intuit, a provider of business and financial management solutions for small and midsize businesses. “If I see somebody getting significantly underpaid or significantly overpaid, it’s almost always [because] we did a bad job of setting the quota, not structuring the plan.” A balanced combination of a good compensation plan and a strong quota-setting process will likely get the organization closer to its growth goals.

Quota problems are consistently at or near the top of the list of sales compensation challenges for most companies. In our work, we see about 30 percent of companies that do not have quotas ready at the beginning of the year. This is alarming because a company’s reps could continue on the path of last year’s quota for months, all the while knowing that they’ll likely be charged with a big increase before the year’s end. For compensation to be a good communications tool, reps need clear direction on what the company wants them to do.

About half of the companies that set quotas adjust them at some point during the year. Some do it for legitimate reasons: because they shifted strategy, they altered territories, or an anticipated product didn’t launch. Others do it to manage pay. You may have heard the humorous term “Incentives Been Managed” from a few employees of one well-known company. Companies may find that some reps are earning beyond an anticipated range, so they raise or redistribute quotas. We don’t advocate changing quotas during the year if at all avoidable unless there’s a significant change in the growth plan or how the team aligns to the market.

Some Challenges with Quotas

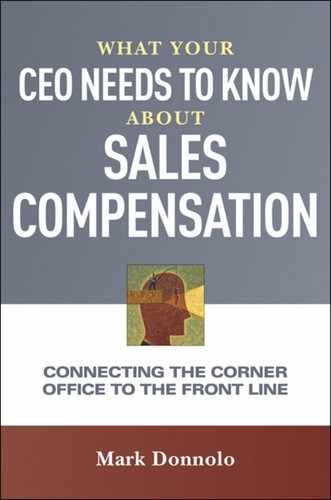

SalesGlobe recently conducted a survey of sales leaders. Figure 6-1 shows some of the biggest quota-setting challenges companies face today, according to the survey.

FIGURE 6-1. QUOTA-SETTING CHALLENGES.

![]() Quotas are driven by historic information that does not represent the opportunity in the market. The natural tendency of most organizations is to consider recent historic performance of the rep or the team and add something to that. However, planning ahead by looking in the rearview mirror doesn’t usually account for the true untapped growth opportunity in a territory or the unrealized capability of the salesperson.

Quotas are driven by historic information that does not represent the opportunity in the market. The natural tendency of most organizations is to consider recent historic performance of the rep or the team and add something to that. However, planning ahead by looking in the rearview mirror doesn’t usually account for the true untapped growth opportunity in a territory or the unrealized capability of the salesperson.

![]() The organization doesn’t have an effective process to accurately set quotas. Quotas are often set by some method that’s not seen as accurate or reliable. Whether there is a good process or not, the perception that the process is ineffective can be just as big of an issue.

The organization doesn’t have an effective process to accurately set quotas. Quotas are often set by some method that’s not seen as accurate or reliable. Whether there is a good process or not, the perception that the process is ineffective can be just as big of an issue.

![]() The sales organization doesn’t believe in the quota-setting process. The organization may have a process. Managers and reps may even be part of the process, giving their “bottom-up” input to what they think is attainable in their territories. However, the mystery is that no matter how much input the field provides, the number still comes back as if it was a completely top-down decision. Reps and managers wonder why they should bother.

The sales organization doesn’t believe in the quota-setting process. The organization may have a process. Managers and reps may even be part of the process, giving their “bottom-up” input to what they think is attainable in their territories. However, the mystery is that no matter how much input the field provides, the number still comes back as if it was a completely top-down decision. Reps and managers wonder why they should bother.

![]() The organization doesn’t have accurate information to set quotas. The organization would like to set quotas well, but the data doesn’t exist or isn’t reliable. This was a more common issue a decade ago, but with ever improving customer and market data, the possibility of setting good quotas is now better than ever.

The organization doesn’t have accurate information to set quotas. The organization would like to set quotas well, but the data doesn’t exist or isn’t reliable. This was a more common issue a decade ago, but with ever improving customer and market data, the possibility of setting good quotas is now better than ever.

![]() Quotas create a performance penalty in the next year for high performers. The organization perceives that a good year will be met with an unrealistic growth expectation for the following year. This can be a real hurdle for the rep if some of last year’s great performance came from a sizable onetime deal that isn’t realistically repeatable year after year.

Quotas create a performance penalty in the next year for high performers. The organization perceives that a good year will be met with an unrealistic growth expectation for the following year. This can be a real hurdle for the rep if some of last year’s great performance came from a sizable onetime deal that isn’t realistically repeatable year after year.

![]() The quota-setting process is not transparent, and people don’t know how their quotas were set. A number comes to the rep on a sheet of paper or by word of mouth without a clear explanation of how it was developed. Sometimes managers and reps think of this as spreading the pain because the overall number may simply be seen as unachievable.

The quota-setting process is not transparent, and people don’t know how their quotas were set. A number comes to the rep on a sheet of paper or by word of mouth without a clear explanation of how it was developed. Sometimes managers and reps think of this as spreading the pain because the overall number may simply be seen as unachievable.

While quota setting is often thought of as a quantitative, numbers-driven discipline, four of the top six challenges presented above are not related to the numbers but instead are related to the process, the people, and their belief in the process. Quota setting is as much a people challenge as a numbers challenge.

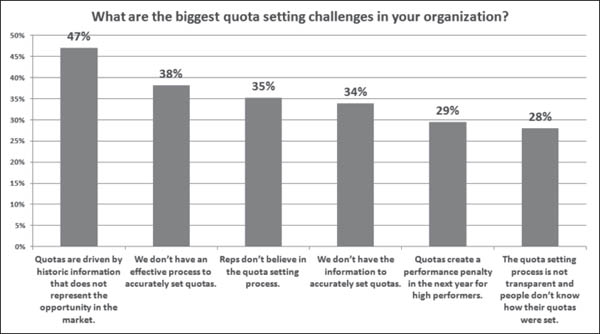

These problems can’t be ignored. Most companies recognize the dangers that come from not resolving their quota issues. Our survey results also indicated the risks companies face by not resolving their quota problems, as shown in Figure 6-2. These risks include de-motivation of the sales organization, missed growth targets for the business, high sales organization turnover, and lower impact of the sales compensation plan. For some organizations, bad quota setting has a domino effect. A pattern of missed goals over a period of years can create a trend of decreasing company performance. Quota setting can ultimately impact the company’s top line growth.

FIGURE 6-2. RISKS OF NOT IMPROVING THE QUOTA PROCESS.

The Forensics: Do You Have a Quota Issue or a Sales Effectiveness Issue?

Sometimes what looks like a quota issue is actually something else. Thinking back to the Revenue Roadmap from Chapter 1, what shows up as a downstream quota issue in the Enablement layer may actually be a symptom of another sales effectiveness challenge further upstream in the Customer Coverage or Sales Strategy layers. When you examine your organization’s quota performance, one of the first visuals you’ll likely see from your team is a histogram distribution of quota attainment, similar to Figure 6-3.

This example, from a technology hardware company, shows the number of reps who reached a certain percentage attainment of quota. Reps are divided into 10 percent performance groups—for example, from 20 percent to 29 percent of quota on up to the quota dotted line and above. In most high-performing sales organizations, we see about 50 percent to 70 percent of reps at or above quota with a fairly normal or bell-shaped distribution. This ensures that most of the group is reaching quota and that the company is at or above quota overall.

FIGURE 6-3. QUOTA ATTAINMENT DISTRIBUTION.

Occasionally, an executive wants quota attainment to be a special occurrence, with only about 30 percent or 40 percent of reps at that level. While this type of distribution may still work, it puts the majority of the organization in a situation where sales-people see themselves as below-standard performers—not the best frame of mind for a sales culture. Also, it’s unlikely that the organization will reach its goal with that type of performance distribution, and it may rely on heavy over-allocation of the quota to reach its goal.

In the example shown in Figure 6-3, only about 20 percent of reps are at or above quota for their primary revenue measure. This pattern had continued for the company for a couple of years, and it appeared that the organization had a quota problem. The questions came up: “What’s causing this? What is the situation?” Very often a company gets to this point and says, “The distributions are bad, so we need to fix quota setting.” But it helps to try to figure out what’s going on underneath that. Snapping on our rubber gloves and digging into our forensics kit, we looked at how the quota situation in this company had evolved over the past few years. Sure enough, a trend of quota attainment comparing one year to the next revealed something.

In an environment of steady performance, a company might expect to see reps consistently performing to quota. A rep might be a 100 percent performer two years in a row, moving along pretty consistently, or some reps might be consistently above or below quota. But Figure 6-4 (regarding the same company) shows a shotgun distribution—complete randomness. The R squared shown on the graph is a statistical measure of how well the trend line fits with the data points or explains the data points. An R squared of 1.00 would indicate a perfect fit to the line and perfect consistency if each rep performed exactly the same from one year to the next. The R squared of 0.10 in this situation indicates that the trend line explains only about 10% of the variation of the data points . . . a very low relationship. Someone who did well on quota attainment in year one might have done very poorly on quota attainment in year two. This pattern of randomness continued over several consecutive years. We also ran the same type of analysis with the actual quota dollars assigned to each rep, and we saw a similar type of scattered distribution. So one year, a rep’s quota might be high with low attainment, and then the next year, it might be low with high attainment. This can be a symptom of a quota process that reacts to recent historic performance. These results beg the question: Is this a quota-setting problem or is it a performance issue?

FIGURE 6-4. YEAR-OVER-YEAR QUOTA ATTAINMENT.

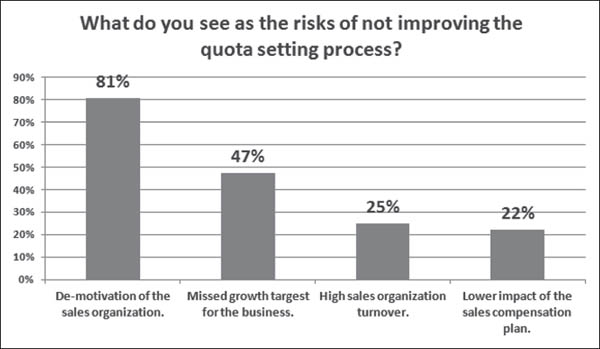

Next, we removed quota from the analysis and looked simply at absolute sales performance, as shown in Figure 6-5. By examining just the revenue dollars booked from year to year, without considering quota, we saw a very different pattern. These are the same people over the same time periods, just viewed by sales performance.

FIGURE 6-5. YEAR-OVER-YEAR BOOKINGS.

We looked at this trend of over a series of years and found that the year-to-year trend is much tighter. It showed people were chugging along at a certain rate and tended to run pretty consistently in terms of actual revenue bookings performance. We took a few other cuts of the performance information and found that while the organization performed relatively consistently, there was a true sales performance issue with a good portion of the organization operating at consistently low bookings levels. This was largely related to salespeople’s sales process and competency in the role.

The quota-setting process in this company was ill-defined, had minimal field involvement, and was largely based on historic performance, which created dramatic quota changes from year to year. We also found that over a period of years, the organization was trending downward in its goal attainment and would likely miss its goal within the next year, as shown in Figure 6-6. The quota and performance issues were bubbling up to a larger company performance risk.

This forensics snapshot illustrates the broader implications of a quota-setting symptom and the fact that most challenges like this are a combination of quota and performance issues.

FIGURE 6-6. DECLINING COMPANY GOAL ATTAINMENT.

10 Success Factors for Better Quotas

So what makes good quota setting so challenging? We see 10 issues that make a difference when setting quotas. Knowing the causes and leveraging these success factors could help you set clear quotas for your organization.

See Beyond a Single Number

When executives design a good sales compensation plan, the team steps back and admires the final product. To the design team, it’s not just a sales compensation plan—it’s a sales compensation program. To those who developed the plan, it may be a work of elegance and intricacy, because sales compensation plans for the entire organization can be a complicated and exhaustive logic puzzle. When the plan is presented to the salesperson, the first thing she does is read through it—carefully.

The quota, by comparison, is simply a number. It carries the same level of impact as the sales compensation plan, but it often is not given the attention it requires. It’s $5.3 million or $24.6 million or some other number. Regardless of how high or low the number is, we know one thing for sure: Nobody really likes his quota. It’s not elegant. It’s not intricate. The thinking that went into setting the number may not be apparent. From a rep’s perspective, his boss might have just come up with that number yesterday to try and dole out the punishment from above. In truth, the work that goes behind a good quota may not be simple at all. You need to emphasize the importance of a good quota-setting process and not let its seeming simplicity minimize its significance.

Remember the People

As we saw from the top challenges discussed earlier in the chapter, quota setting is about the people and the process as much as the numbers. If managers and reps are in the dark, or if their input isn’t reflected or explained in the result, then you may as well just give them a number. If they understand the process, the process is transparent, they have input, and they see the results of their input, then the resulting quota will be better received by all.

Involve the Right Team

Quotas involve a different set of players than sales compensation. During the sales compensation process, sales or human resources is often in the driver’s seat. With apologies to finance organizations across the world, many wild quota-setting rides begin and end with these very bright finance people behind the wheel. Unfortunately, finance—unlike the front line—rarely has visibility of where the market opportunities are. Instead, finance’s vision is usually set to investor requirements for growth. Finance often needs some market-sensitive guidance. Make sure the quota-setting team, including finance, is oriented toward market opportunity as well as corporate growth expectations.

Jay Klompmaker, longtime professor of business administration at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, likens the necessity of including both finance and front-line sales reps in the quota-setting process to the old anecdote of a group of blindfolded people each feeling only one part of an elephant. “One group feels its leg and thinks it’s a tree. Another group feels only its trunk and thinks it’s a snake. But multiple perspectives are critical to understand the whole situation. With quotas, you have to include the top and the front line. You get a much better view of what’s happening if you include both groups. And, you’ll get more buy-in and active participation from that sales force when they’ve got some role in that quota setting,” he says.

Don’t Get Lost in the Legacy

One of the most popular quota-setting approaches is called “the way we’ve always done it.” This familiar but flawed quota approach has a way of living on like a crazy old aunt who shows up at Thanksgiving. She may not be perfect, and nobody can understand her, but we only have to deal with her once a year, and that’s easier than changing our address. If your quota process isn’t working, be a champion of change, not a defender of the legacy.

Get a View from the Bottom-Up

One of the easiest ways to set quotas is to divide the big corporate number and allocate it down to the organization in some pro-rata fashion like size of territory or portion of total sales. While it’s easy, it’s also a one-way street from the top of the organization down to the field that usually results in a disconnect and reluctant quota ownership by the field. By combining a bottom-up view with the top-down expectations, you can consider granular information from the field on account opportunity and reconcile it with a bird’s eye view of how that opportunity looks across markets and overall macro forecasts or trends for market growth.

Andy Summerfield, sales director for Everything Everywhere—the UK’s largest mobile operator—follows a bottom-up, top-down process. “We choose a target setting that’s at a budget level,” he says. “So when we’re building the budget from bottom-up, in the July timeframe for the following year, we work out what will happen to our existing base, what level of dilution we can tolerate, and what we need to add into the top in terms of acquisition. And the budget then tends to drive out the KPIs [key performance indicators] and the metrics that we translate straight into targeting. Then we do the usual of adding some stress to go with the buffer across all of those models. The process works very smoothly for us. If all of my sales guys hit their relevant numbers, we know that we will comfortably hit our budget.”

Move Beyond History

Most organizations set quotas by looking backward. Historic sales performance may be the primary driver of the quota, which is usually determined by taking a snapshot of the most recent year’s performance and applying a fairly standard growth rate on top of that performance. This historic approach is the source of most performance penalties that simply add a bigger expectation on top of a rep who had a great sales year. Historic quota setting may also create a “porpoise pattern,” where sales and quota attainment leap up and then dive in alternating years. For example, a rep with great revenue performance (a leap) in year one, resulting in an inflated quota in year two, often has low attainment of that inflated quota (a dive) in year two. Of course, this may then lead to a lower quota in year three, followed by another leap in great performance over that low quota. And so the pattern continues. Challenge your team to acknowledge history but to lean toward forward-looking indicators of market opportunity.

Balance Market Opportunity with Sales Capacity

Market opportunity should be a primary driver of the quota. More specifically, territory opportunity relative to other similar territories can give you a good indication of what portion of the total goal should be allocated to each territory.

Indicators of territory opportunity may be characteristics of accounts that correlate with revenue potential. For instance, a company in the bar-code scanning business determined that the square footage of a retail grocery store and the number of beds in a hospital were both metrics that were predictive of the potential annual sales for its scanning solutions. By applying a formula to all customers and prospects in a market or territory, the company got a relative sense of the sales potential across all markets or territories. But that indicator of market opportunity was only half of the answer. The other half was the practical physical ability, or capacity, of the sales force to close a certain amount of business. This sales capacity considers the number of hours each rep works in a year, the percentage of that time that is spent actually selling versus handling other operations and administrative activities, and the productivity of those selling hours given the time it takes to manage or close an account and close rates.

Fifteen years ago, Jeff Connor of ARAMARK had a sales force that was cut from 25 reps to 15, but the quota went up. He describes the situation:

The executive for whom I was working at the time had some bold leadership traits. He walked into the meeting and said, “I’m doing away with quotas. I don’t know what the right number is. I know you guys are the best of the best and it’s a big market. Now, my number is $100 million, and there are 15 of you. So you can all go figure it out if you want. But there are no quotas, and I’m not measuring to a quota. I want to see what we’re capable of as a team.”

And guess what happened that year? That team sold about $127 million. It was the best number ever—highest per person—and we never set a quota for anybody. The organization had a target and there were a certain number of people, but there were no incentives at the target. The compensation plan paid off of what they drove home for the business. To some extent he set the people free. It was a powerful enabler to say to your people, “You’re the best of the best, and I just don’t know how good you can be.” He’s a motivator and a very good team builder, and kind of an impassioned leader. I don’t think everybody can get away with that.

By understanding and balancing the two sides of market opportunity and sales capacity, you can get a multidimensional view on how to allocate the quota.

Fit the Methodology to the Account Type

One quota-setting approach does not fit all situations. While a more analytically-driven, standardized quota may work well for small accounts with a transactional sales process, a more bottom-up market opportunity approach might be better suited for a midsize account segment. Near the top of the account pyramid, national account quotas may be more accurately based on the information and strategies developed in an account plan. That account plan might provide input for quotas and also serve as a planning and coaching tool for sales managers to use with their account managers. Apply an appropriate approach for each type of segment or market.

Make Your Approach Scalable

A telecommunications organization we worked with had reengineered and piloted its new quota process, which incorporated top-down and bottom-up inputs, predictive market data, and precise steps for the entire team to work through the process. It all worked well during the pilot phase, only for the company to find out after full introduction that the process was just too complicated, delicate, and unwieldy. The process that worked perfectly in a contained environment just couldn’t scale in the organization without coming apart at the seams. Further, it was creating workload demands to manually manage steps and exceptions that weren’t captured in a non-scaled environment. Err toward the side of simplicity. Accounting for every possibility may not be much more accurate but can certainly be much more manpower-intensive than using a simpler, streamlined approach.

Don’t Over-, Over-Allocate

A sales leader in a Fortune 100 transportation company recently asked me a very straightforward question: “Why is it that our CFO reported to Wall Street that we were on plan for revenue for the quarter, yet leadership is beating on us because we’re behind plan in the field?” As we examined the question, the answer became clear. It was a case of over-, over-allocation of the quota.

Over-allocation refers to the approach of taking the sales goal for the business overall and, as it is allocated to the next level of management, adding a little extra to that goal. The sum of all unique, non-overlapping front-line sales quotas compared to the company’s goal is a simple measure of quota over-allocation. For example, a company with a $1 billion corporate goal with a sum of all front-line quotas of $1.05 billion has over-allocated its goal by 5 percent. Most organizations over-allocate quotas by about 3 percent to 5 percent from top goal to front line. That little extra allocation acts like an insurance policy. If the manager has a sales position that remains unfilled for a period of time with no one to effectively cover that territory, the over-allocation makes up for some of that loss. If a rep falls dramatically short on his quota, the over-allocation also makes up for some of that performance shortfall.

Over-allocation, within limits, can keep the organization on track with its quota. However, when the quota is over-allocated too much at too many levels, it can lead to distortion on the front line. In the case of the transportation company, the company had over-allocated its goal to a point where the C-level and the front line had two different realities. The sun was shining at the C-level while the front line saw only cloudy skies. Keep your quota allocation trim so that executives and reps all participate in the company’s success.

From History to Opportunity

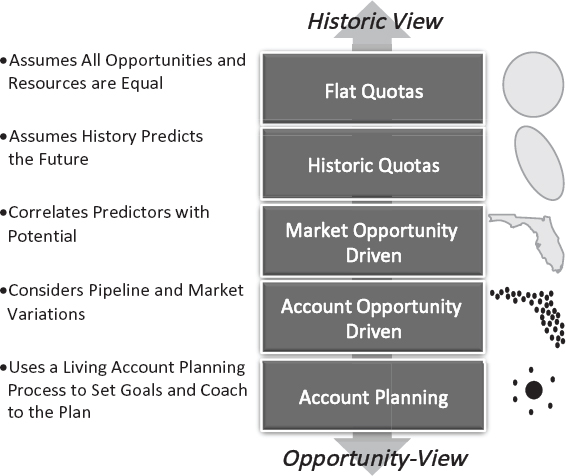

Quota-setting methodologies vary based on the market and types of accounts. Approaches can range from one-size-fits-all to a historic view to a forward-looking opportunity view, as shown in Figure 6-7.

FIGURE 6-7. QUOTA METHODOLOGIES.

1. Flat quotas are simple and effective in the right situations. An organization often starts out this way or may use this approach in new markets it enters. Everybody gets the same quota because it is assumed that all opportunities and resources are equal. While this may seem like a primitive approach, it can be effective in environments with unconstrained opportunities where there is abundant sales potential and the capability of reps is similar. The flat quota approach is common in new business development situations where reps don’t have an existing base of business to manage and may have few boundaries to their sales opportunities. It’s survival of the fittest.

2. Historic quotas are the most common in companies, yet they create some of the biggest issues by assuming that history is predictive of the future and of potential in a market. This approach creates quotas that recreate history. A majority of companies use a historic quota-setting process either primarily or in combination with other methods. While history is a good starting point for setting quotas, it should be enhanced by turning the attention to future opportunities.

3. Market opportunity–driven quotas are developed by starting with historic information and building on it based on the characteristics of the market. Market opportunity might consider predictors of potential that indicate how much opportunity might reside in an account. For example, the number of employees at an account location may be correlated to revenue potential. Those indicators can become part of a larger predictive model that either estimates the potential of a territory or compares that territory with other territories to help allocate the goal correctly across those territories. This approach can be effective for a large number of accounts.

4. Account opportunity–driven quotas consider characteristics of the accounts as well as the market. By looking at the sources of revenue retention, penetration, and new customer acquisition, as well as the existing and planned sales pipeline, a sales organization can build the account opportunity components from the bottom-up. Those growth estimates can be compared with top-down intelligence on the overall market and with growth predictions. The company can also consider sales capacity and the capabilities of reps to capture that account opportunity.

5. Account planning can be used for growth planning, for coaching reps to the plan, and—of course—for setting quotas for the account. This process is effective in situations where there are a small number of large accounts. The account plan provides information on growth targets in the account as well as tactics the team will use to grow the customer relationship.

By considering and combining these five methods, the organization can develop a quota-setting approach that matches each type of account segment and can increase the opportunity to hit the company’s overall sales objective.

5 QUESTIONS YOU SHOULD ASK YOUR TEAM ABOUT QUOTA SETTING

1. How do we currently set our quotas for each segment and account type?

2. Do we have a historic view or a future sales potential view on quotas?

3. Are the challenges we have quota issues, or are they broader sales performance issues?

4. How do managers and reps get involved in the quota-setting process?

5. If we change the process, how could it affect overall performance?