CHAPTER 7

Managing Sales Management: Understanding Roles and Rewards

LAUREN ENTERED THE DOCTOR’S OFFICE with a sense of familiarity and confidence. She walked up to the receptionist and politely announced herself, but it was clear the receptionist knew her. I was shadowing one of the top reps of a leading pharmaceutical company, and we were on our third visit that morning to a medical group practice in West Los Angeles.

“These practices are getting more restrictive with reps,” Lauren told me. “The doctors used to be glad to spend time with us, but now it’s tougher than ever to get a few minutes to go over updates. With more workload and administration, less time with patients, and nurses covering the overflow, just getting a little mindshare from any of the doctors is a challenge. I’ve been fortunate enough to build some great relationships, and they know I’m not going to waste their time.” As a top rep, Lauren had earned a position as a sales manager, but she had recently returned to the field.

“Why did you go back to carrying a bag?” I asked.

“If you do well, the path is usually to move into a district sales manager role and maybe continue on into another management role after a few years. It was great being a manager, but in the end I just couldn’t afford the opportunity. It was more about the vision of being a district sales manager than it was about the compensation that you could earn. I made a lot more as a rep,” she said.

Lauren had tried to explain to her husband that assuming a management position was a good move, but as the bills got tight, they had second thoughts. “In the end, financially, it just didn’t make sense for me to take on the additional responsibility and hours of managing people and worrying about their problems while I was worrying about how to get my own pay level back up to where it was before,” she said.

After a number of similar conversations with other reps, I talked to the CSO and learned that Lauren’s situation wasn’t uncommon for the company. He said:

We just can’t make sales management positions attractive enough for our best people. We show them their career path and future with the company through management, but frankly, we struggle to make it as financially attractive as what they currently earn as high-performing reps.

When we do get them into management, they’re supposed to plan their piece of the business, coach and develop their team, and hit some pretty aggressive growth numbers. But most of the time, their version of coaching is going on sales calls with their reps and jumping in the front seat to close the sale rather than teaching them how to do it. It’s like we’re taking a group of Michael Jordans and asking them to coach the team. Most of them are more talented on the court than leading and coaching from the sideline.

As we looked at the situation with the CSO, we discovered that the solution lay in a combination of factors that included defining the role of a successful sales manager, identifying the profile of the right type of person for that role, and developing an attractive value proposition for sales managers that would make it worthwhile for a high-potential rep to take the next step into a career in management.

Sales Managers Aren’t Just Big Salespeople: What Does It Take?

Top salespeople don’t always make the best sales managers, but this is often the path that companies lay out for salespeople. In a large percentage of cases, those newly minted sales managers struggle with their role in leadership beyond selling.

Jeff Connor of ARAMARK says, “Managers were often successful salespeople before they became managers. But they were almost never the most successful salesperson. The person who fights to be number one all the time as a direct seller usually does not make the transition to leader very well. But by the way, they were never average, either. You can’t have just an average salesperson suddenly thrust into a leadership position.”

Al Kabus, former president of Mohawk Commercial—a publicly traded supplier of flooring—agrees. He states:

There’s a time that you go from being a salesperson to a leader, and that is a real challenge. You go through the normal progression of sales to regional manager to vice president to possibly getting the nod to run a division or become a GM or a president. Sales professionals often get promoted because of how well they did in sales, and that’s not what makes good leaders.

The idea of what leadership is, to me, falls into three brackets. One is you need to deliver your results clearly. Two is you need to remove obstacles to getting to those results both for your team and the organization. And the third thing is you have to grow your talent. You have to make sure the right people are in the right seats in the right places, and you have to be committed to making them better under your watch than they were before you came in.

The skills and competencies that it takes to be an effective sales manager are different from what it takes to be a successful seller. When we look at the qualities of a successful sales manager, they include the talents and assets discussed below.

They Understand How to Lead

Many top salespeople are carried into management by the sheer momentum of their success at selling. But, as we find in most management and leadership roles, what it took for the person to advance to that role and what it takes for her to thrive in that role may be very different.

A manager has to learn to make the transition from doing the selling to leading the process and the team. If a manager uses her sheer talent at selling to lead the team but ends up just selling alongside them instead of leading, she’ll soon be limited by her physical capacity to sell. A good manager “gets airborne” and pulls up above the personal selling, disseminating her talents to her team through leadership. Some companies use a hybrid selling sales manager role in which the individual leads and sells. While this can be a good transitional strategy and can allow the organization to match some of its sales manager costs to a unique quota for that manager, in the long run, the organization is breeding flightless birds. Organizations that continue to allow their sales managers to run rather than to fly above the troops never get the leadership leverage that will take the team to the next level of sales productivity. Jay Klompmaker of the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School says:

We know from research that salespeople have a very strong ego drive and take pride in being good salespeople. All great athletes have that. Their ego drives them. And I don’t mean that in a bad way. I mean they get personal fulfillment from excelling. They are very inner-directed, and they enjoy seeing their own personal efforts driving those results.

But as a sales manager, they need to have in their personality the ability to enjoy the success of others, because their job is to have the people that work with them be successful. I like to see those guys have some skin in the game, so as their salespeople achieve greater levels of incentive comp, they’re rewarded. They get some piece of it, or a measure relates to it somehow, so their total comp has a portion of it that’s based on the success of their salespeople.

They Strategize the Growth of Their Organization

A successful rep in a field sales role may reach his quota through 20 percent strategizing and 80 percent hustle and execution. However, a sales manager has to flip that ratio. Running harder won’t help the team reach its goal as well as developing and implementing an effective strategy, based on aligning the team’s talent to the right opportunities in the market, will. An effective sales manager has to work according to a first-line manager version of the Revenue Roadmap. While the Sales Strategy layer may have been decided by the organization, he has to develop a methodical approach to sensing customer needs at the Insight layer, planning his sales process and deployment of his team at the Customer Coverage layer, and supporting them with the right teaching and tools at the Enablement layer.

For most new sales managers, as well as many experienced sale managers and sales directors, this type of thinking does not come naturally. Good sales organizations teach and coach their managers on how to think like planners and leaders, giving them the tools they need to prevent guessing and trial and error when it comes to planning for growth.

They Are Creative at Planning and Systematically Solving Customer Problems

The strategy and planning described above is not a mechanical process. It requires a creative problem-solving approach as well as flexibility and adaptability. To describe it simply, most sales-people either operate analytically, working the pipeline and numbers, or they shoot from the hip, working according to their gut. As a salesperson progresses in her career—for example, from a transactional seller of small and midsize accounts to a strategic seller of major accounts to a leader of a sales team—she also makes a gradual transition from left-brained analytical and executional thinking to a combination of left-brained and right-brained creative problem-solving thinking. If a sales leader operates from a single side—say, too analytically or too intuitively—then she risks running the team with that imbalance.

An effective sales leader develops the ability to creatively plan how the team will reach its goal and, on a frequent basis, how to creatively solve customer problems and differentiate from competitors. We use a process we developed called the Creative Sales Quotient that helps sales leaders apply a proven, creative problem-solving process to develop better strategies for their businesses. It also helps front-line sellers and sales teams rapidly create new ways to develop customer solutions and win deals. It combines the left-brained sales processes with a method of predictably innovating and differentiating from competitors. If a sales organization just repeats what it has done before or copies competitors, then it merely repeats the status quo and blends in with the white noise created by competitors.

They Are Effective at Coaching and Developing Their Teams

Coaching is a critical role for sales managers. However, companies talk about it more than they do it. In a recent survey of sales leaders conducted by SalesGlobe, 84 percent of companies ranked coaching as either “very important” or “one of the most important factors of sales success” for their organizations. Despite its importance, when we ask managers about how much time they spend on coaching compared to other activities in their role, we often get a puzzled look as they think about their full range of responsibilities, including coaching.

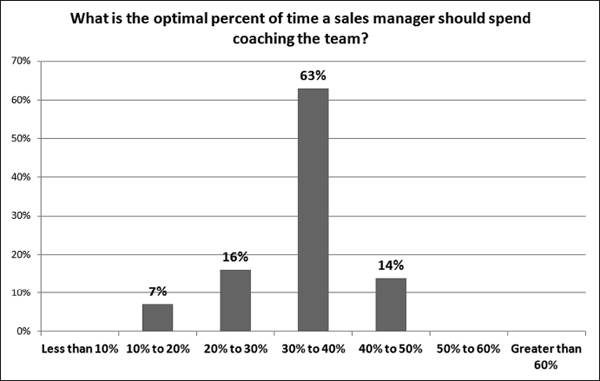

The fact is spending time on coaching is a challenge for most managers. Sales managers don’t put the necessary time into coaching because of time constraints, priorities, habit, or avoidance. We asked sales leaders how much time sales managers should spend coaching their team. According to the results, shown in Figure 7-1, most leaders (63 percent) say that their sales managers should spend between 30 percent and 40 percent of their time on coaching. But the reality is most sales managers spend only about 15 percent of their time coaching.

So what holds sales managers back from coaching? According to the results of that same survey, shown in Figure 7-2, a major challenge is making the time. Sales managers are held back from coaching because they are too busy with other management responsibilities (70 percent), which are often administrative or operational, or too busy with other sales responsibilities (47 percent), indicating that they are actually selling. Another challenge area is making coaching a priority, as managers simply don’t make the time to coach (40 percent) or are not required to coach (14 percent). Finally, given the time, sales managers may not know how to coach effectively (44 percent) or do not have a methodology for coaching (19 percent).

FIGURE 7-1. OPTIMAL COACHING TIME.

Focusing managers on coaching comes down to having leadership make the mandate for coaching clear, building a coaching program and methodology that fits the organization, freeing up time for coaching, and making the process transparent and measurable so the team can see the actions and results from effective coaching.

FIGURE 7-2. SALES COACHING BARRIERS.

They Sell in the Right Places

Yes, sales skill is still a big part of the sales manager’s role. Leaders from front-line sales managers up to the CEO continue to play a critical role in direct customer selling and relationship management. The situation described in Chapter 5 regarding the CEO building the relationship with the global customer’s CEO in London illustrates a common role for senior leaders. As the sales team organizes its facings to the customer (which team members face off with which customers), everything needs to match all the way up the organization chart like good man-to-man or zone coverage on a basketball team. While the sales manager should resist jumping in and selling for the rep, he should play an ongoing role in building relationships at and above the level where the sale rep is working.

The sales manager also plays an important sales role internally at his own company. As Al Kabus described, one of the important roles of a sales manager is removing barriers for the sales team. This means finding ways to allow salespeople to maintain their focus on selling, rather than other non-selling roles and distractions, so they can meet the goals set out for them. Often, removing barriers involves selling internally, making the case, and sometimes persuasively laying out the arguments for why the organization must do something differently than the way it’s always done it. So sales mangers do continue to act as sellers, although it’s just one important part of the total job.

What Motivates Managers?

Moving up the career path from front line to management, motivators typically shift from near-term cash incentives to those that promote a more strategic view of the business. Rather than looking solely at quarterly performance in the territory, a company may want a manager’s focus to swing toward the mid-term goals that create sustainable growth for the business. Of course, this quarter’s revenue and profit performance are always at or near the top of the list, but continued future growth also comes from working on a time horizon that captures the planning and development of the organization.

To enable this shift in strategic view, the company must prepare managers to think and work in those terms at the upper layers of the Revenue Roadmap. A company can’t ask a top performer rising from sales into management to show up on Monday morning as a new manager and expect him to do anything other than his interpretation of what a manager should do, unless the company prepares him. Many companies have sales management development programs and management universities to build capabilities for the new role. But if a manager still has a short-term view supported by incentives, the organization may be missing a step at the Enablement layer of the Revenue Roadmap.

The company has to match the business view with the right motivators. BJ Schaknowski, vice president of solution provider sales for CA Technologies—an IT management software and solutions company—agrees that retention of the best reps can be a problem. He says:

There are no pension plans. Companies don’t even give equity like they did 10 years ago. For a high performer, the reality is the internal trajectory for them cannot keep pace with their external marketability. Keep their internal trajectory in line with their market opportunities to make sure the trajectory of the market opportunity doesn’t outpace their internal trajectories, so you could hold onto them.

What typically ends up happening, even with a highly engaged, motivated young sales leader, if she doesn’t see the next step, that career progression, she’ll go find it somewhere else, even if in a lower level company. We spent a lot of time talking about this, and we started rotating sales-people through other leadership functions in the company, almost doing a rotational development program. We try to create a culture of talent—we called it mobility. It could be lateral mobility, but if you’re getting the opportunity to do more sideways jobs, that’s preparing you. When the next big job opens, you’re best in line. Lateral mobility through the organization—in addition to taking care of the financials—helps retain your best people and broadens their skill sets. So when they come back to sales, they’re better overall leaders and they have a good understanding of what drives the rest of the organization. Lastly, it’s the best identification tool for succession planning that you’ll possibly see.

The career “offer” for sales managers goes beyond short-term incentives and incorporates several important pieces that can align managers with the goals of the business. Let’s take a look at the Sales Management Offer, shown in Figure 7-3, and how you can use its components to motivate managers.

FIGURE 7-3. SALES MANAGEMENT OFFER.

Role and Recognition Rewards

The sales management role itself can be a motivator based on its increased responsibility and position in the organization. When I reflect back on my teenage years in Boy Scouts, I think about what it meant to reach the top—to become an Eagle Scout after years of braving the elements, camping in the frozen forest without a tent while listening to the howl of not-too-distant coyotes, and leading endless service projects. The reward was the accomplishment and the acknowledgment. (As I remember, they didn’t pay us anything as Boy Scouts.) Companies that celebrate advancement to management and honor the accomplishments of each individual increase the value and incentive of the sales management role.

After promotion to sales management, the organization has opportunities to provide additional recognition for significant accomplishments. While recognition can be delivered naturally by executives who use it as part of their leadership style, it is best delivered in a consistent way across leaders in the organization. For example, a CEO of a technology company told us about a simple, two-part method that he suggests his sales executives use with their managers. The first involves the written word. He suggests that they periodically use short handwritten notes to their managers to acknowledge accomplishments. Jotting down just a couple of sentences on a sheet of notepaper and leaving it on the manager’s desk conveys a personal message that cuts through the blur of e-mail traffic. This CEO also mentioned that these notes, if used judiciously, have a lasting value. He described his visits to sales offices and noticing his old notes, saved from years earlier, pinned to bulletin boards in managers’ offices.

The second part of this CEO’s suggested method involves leaving short voice mail messages for sales managers and thanking them for certain recent accomplishments. The CEO takes advantage of his travel time between airports and offices to work through a short list of thank-you calls. If he and his sales executives didn’t plan these possibly obvious and simple approaches, there’s a good chance they would be caught up in the pace of their work and miss those opportunities. Amid a range of possible elaborate recognition approaches, a simple personal “thank you” costs nothing and perhaps has the greatest impact of any form of recognition.

Career Map

Successful reps who advance to sales management have already experienced a major step in the career path. There could be much more ahead. The sales management career path may actually be more like a career map, followed more deliberately with more forethought, planning, and more than just one possible route. This variety of options can create intriguing possibilities for the individual and the organization. Many organizations have a well-worn route that defines how a salesperson can advance to district management, region management, and above. In these organizations, the question sometimes arises about how to advance high potential people when there’s a traffic jam in the traditional career path. A career map, with alternate routes, can open up new possibilities.

With increased specialization in the sales organization around customer segments, services, and products, the opportunities for new customer-facing paths have emerged that are increasingly valuable for the company. Sales operations, a function that plays a critical enabling role to sales by increasing its overall productivity, has a dire need for qualified talent in a majority of companies. In fact, attracting top talent from within the organization is one of the top challenges in sales operations. Sales operations teams have become more defined and specialized in their roles. From our research, more than 50 percent of companies take the lead within sales operations on performance analytics, sales process definition, CRM (customer relationship management) and tool development, sales compensation, and sales team training. More than 40 percent of these companies have teams that are structured specifically for these functions. This fact points to numerous potential routes in the sales management career map. Charting out the future opportunities, reinforcing that message, and providing continued career counsel can enhance the future view of the Sales Management Offer.

Investment

This component of the Sales Management Offer is usually present but often underemphasized. Most businesses invest in their sales managers from the day they begin in management and continue throughout their careers. Ron Cox, former CEO of Achieve-Global, a global employee development company, and Acclivus, behavior and performance consultants for sales, support, and service professionals and executives in more than 80 countries, describes this investment. “Promoting a top salesperson to management can have a double impact. You’re taking a top revenue producer out of the field and either taking on a management learning curve or risking potential failure as a leader. An alternative that also worked well for us was to make untraditional moves by transferring great people managers from other functions into sales management. We initially got a lot of resistance, with feedback like, ‘They don’t have any sales experience!’ But it worked out famously, as it also set up another path to senior staff positions,” says Cox.

In addition to the risk the company takes, investment can take the form of management development programs, special projects that are important to the company, rotational assignments to increase the breadth of managers, and learning through university programs. While it is an investment for the company to get some future return, it’s also an investment for the manager that increases her personal value as a leader. Emphasize the value of this investment to the manager in the offer.

One good approach we saw to valuing this investment for managers was with a company in the information solutions business. When the senior leadership team looked at the sales expense portion of the income statement, it was clear to them that they were spending a significant amount annually on their sales management team. Over the past few years, they had sent members of the team to a couple of top business schools for a series of case study programs focused on how to address sales leadership challenges. They also funded several corporate memberships in associations that included travel to conferences for speaking engagements for managers. They had even invested in some individual coaching for some of their high-potential managers. However, sales managers still tended to concentrate on just their direct compensation, particularly when they compared themselves to peers in other competing organizations.

The company decided to put together an annual total rewards statement for managers that included the investments the company made in the development of each manager. While a total rewards statement is not unusual, the company put an additional spin on it, which was to indicate how these investments improved each manager’s future marketability. The statement showed not only how the manager was better prepared to follow the company’s career map but also how the manager was better qualified for future steps in his career in the general market outside the company. While hinting at a manager’s preparedness for opportunities outside the company may sound risky, the company believed that the total components in its Sales Management Offer were strong enough to keep team members aligned to a future with the company. Indeed, if a company is bold enough to show how it’s preparing managers more broadly, it certainly stays sharp on making sure its value proposition to the manager stays strong.

Rewards

With success in the management role, much like the sales role, comes opportunities for rewards. Rewards are usually outside the core sales compensation plan and are geared toward achievements that may be more strategic or more specific. Rewards should have some offset from the incentive plan with what is measured, meaning that the metrics shouldn’t directly overlap what’s tracked with the sales compensation plan. For instance, rewards may be for attainment of a product goal or for an initiative that is not uniquely called out in the sales compensation plan. For sales managers, the measures may be the same as sales (e.g., hitting a quarterly fast-start goal for sales) or may be more unique to management (e.g., attaining a growth and development goal for the district sales team).

In terms of the reward a company provides, noncash rewards are often more impactful than cash. Noncash rewards usually take on a more intrinsic and greater perceived value than cash rewards, which can become blended in with other compensation and disappear into more common uses like paying the bills. For example, a manager may be more motivated by the prospect of earning 80,000 airline points than by earning $800, although both may have about the same value.

Those airline points also illustrate two other characteristics of good non-cash rewards. The first is trophy value. While a manager may not even mention to his peers that he earned an $800 reward, he’s much more likely to talk about the special trip he’s planning with his airline reward. The second characteristic is that good non-cash rewards can be rewarding beyond the manager to the level of his spouse or family. The manager is probably going to use those airline points to book a trip with his wife to a location that she’ll enjoy. Given the hours of hard work that a typical manager puts in and the sacrifice his family makes, this family value can help make the family part of the company team for the road ahead.

Sales Compensation

Of course, sales compensation is a critical part of the Sales Management Offer. Depending on the company and culture, the importance of sales compensation relative to other components in the offer varies. Sales compensation for the sales manager follows the same principles and may share some similar structures with the compensation plan for the salesperson. However, some of the major differences may include measures that track performance at a higher level; measures that incorporate team, customer, and strategic goals; and pay mix that fits a longer time horizon. (We’ll take a look at a few of these approaches shortly.)

It’s important to remember that relying on sales compensation alone for sales managers significantly narrows the Sales Management Offer and puts heavy pressure on one component to differentiate between front-line sellers and managers. This is the challenge the pharmaceutical company ran into earlier in this chapter when it just couldn’t make the short-term cash leap between high-performing sales reps and fledgling sales managers.

Long-Term Incentives

Most companies have a future view of their sales management team and how they’ll develop and retain top players. Long-term incentives can come into play to better align the company’s and sales manager’s time horizons. We’ll not go deeply here into the topic of long-term incentives, other than to mention them as a possible component of the Sales Management Offer. There are numerous sources of in-depth expertise for those who wish to delve further into the topic. For simplicity, we’ll refer to long-term incentives here as a method of reward that pays over a multiyear period for performance that may also be multiyear or within the year.

Probably the most well-known long-term incentive vehicle is company stock, which can take the basic form of incentive stock options (which have the value of the difference between a set strike price and the current value of the stock) or stock units or actual stock (both of which carry the value of the stock itself). Most companies that use stock programs provide an initial grant of units and sometimes subsequent grants—say, annually—to the manager. Stock units that are granted by the company typically time-vest to the manager over a multiyear period or performance-vest sooner based on the manager’s attainment of certain goals, such as reaching a target revenue level or opening a new market for the company. Once vested, when the stock reaches its strike price set by the company, the manager may be allowed to exercise the option and enjoy the reward from the appreciation of the value of the stock. Beyond that semi-technical description, the incentive created by the stock program is for the manager to do whatever is within her power to help increase the value of the stock units, which increases the value of the eventual reward. Since this usually happens over a multiyear period, the manager should have a longer-term view on building the business and wealth.

A company may also design a long-term incentive, without stock, that has cash value that is granted, vested, and exercised in a similar manner. One company we worked with positioned its program to sales managers as its “get rich slow plan” to emphasize a methodical approach to building wealth amid the frenetic competition for talent from tech companies lauding stock options on sales managers with the prospect of cashing in quickly. Often, a cash long-term incentive program includes a few basic measures at the company level or team level that track performance on revenue growth or profit and grant additional value to the manager’s portfolio that can either time-vest or performance-vest. As with stock programs, the company uses the cash program to create a longer-term view for managers.

A Few Sales Compensation Ideas for Sales Managers

There are many options to consider when designing incentive compensation for sales managers. These include the few that follow.

Establish Pay Mix with a Longer View

Using a salary incentive mix for a manager that’s as aggressive as the mix for his front-line reports can promote a shorter-term time horizon. Managers typically have a smaller percentage of target compensation at risk to promote longer-term management and coaching behaviors. Similar to the pay mix difference between the Doberman and the Retriever, a shallower pay mix for sales managers allows them to think a little more strategically and longer-term than front-line sellers who may be more near-term focused.

Do a Simple Roll-Up

A straightforward option for the sales manager is to simply total the results of her reps on the same measures, such as revenue. In this case, the sales manager’s measures might look almost identical to her reps’ measures, except that instead of defining revenue at the individual level, the sales manager plan would define revenue at the team level that the manager controls, like district or region. This approach is simple to understand and communicate and everyone on the team is exactly aligned. A variation of the simple measure roll-up is the incentive roll-up.

Look at Team Participation

While a simple roll-up measures the overall performance of the sales manager’s team, it doesn’t necessarily measure how the sales manager and reps made it happen. One effective approach to increase team involvement is to not just measure total revenue performance to quota but also to measure the percentage of the manager’s reps who reached their individual quotas for the same measure. For example, the manager’s goal may be to get 80 percent of her reps to their revenue quota while also reaching the total roll-up of all reps’ quotas. If the manager attains greater or less than 80 percent of reps at quota, her incentive would scale up or down accordingly.

By measuring team participation in quota attainment, a sales manager can maximize performance by coaching and developing her team members across the board rather than relying on the stellar performance of a few. As with any measurement approach, an organization should test the potential resulting behaviors. We worked with a large business services company a few years ago whose executives told us about their experience with implementing this type of participation measure without fully testing it. They set a sales manager objective to get a certain percentage of reps to quota. However, they did not require sales managers to maintain a minimum level of headcount and fill empty territories. As a result, several sales managers found a loophole and terminated low-performing reps without replacing them. This quickly increased their portion of reps attaining quota but through the wrong means. Rather than prompting sales managers to coach their teams, the company prompted them to trim out anyone below quota—the opposite of what the company expected.

Shift Measures Down the Income Statement

Looking at the higher levels on the organization chart, measurements for managers will tend to shift down the income statement. While an organization may continue to measure top-line performance, it may also include measures that contribute to the bottom line like gross profit or sales expense. It might also capture measures that add the dimension of product mix, customer mix, or contract terms since they may be areas where the sales manager has greater influence and visibility across the customer portfolio than the rep.

Get Objective

Strategic objective measures may also come into play with managers who have goals that are difficult to measure quantitatively. For instance, a manager may be working on milestones that shift from quarter to quarter. These may be easier to evaluate through executive judgment than attainment of hard number goals. Getting a signed contract from a new alliance partner that will help the company advance by modifying its software product to fit the banking industry may be easier for an executive to evaluate than to measure by attaining a revenue goal.

This is just a sample of the numerous methods to align incentives to the unique roles of sales managers. As you think about motivating managers, be sure to clarify the roles that are most important for each type of sales manager, determine the optimal profile for your talent, and create a compelling Sales Management Offer that includes sales compensation.

5 QUESTIONS YOU SHOULD ASK YOUR TEAM ABOUT MOTIVATING MANAGERS

1. What are the most important roles of the sales manager?

2. How should we define our Sales Management Offer?

3. Are we selecting the right type of talent for our sales management positions?

4. What objectives do we need to accomplish this year with our C-level priorities?

5. Does the sales management compensation plan support our priorities with a simple design?