CHAPTER 8

Making Change: Communicating and Implementing the Sales Compensation Plan

JIM, THE CEO of a major staffing and workforce management company, weathered yet another meeting with his senior staff as they combed through the current year’s financials and next year’s projections with the CFO, president, and EVP of sales. The leadership team had worked through the summer months developing the strategic plan for the upcoming year. Summer became autumn and the iterations continued.

This year, the process was taking significantly longer than in prior years. The company’s new private equity (PE) partner, which had recently taken a major ownership position in the business, seemed to have an endless appetite for better ideas and additional “what-if” scenarios. The leadership team’s initial excitement at the term sheet they received from their new partner a couple of quarters ago had dulled as they labored through the due diligence process and had finally, a few months ago, become a proud member of the PE firm’s prestigious list of portfolio companies. As Jim glanced across the table at the two freshly minted MBAs from the PE firm (who practically lived on-site and now sat in on nearly every management team meeting), he worked to keep cordial. The PE guys were polite. They were smart. But they never stopped asking questions—really good questions. And Jim and his team had to listen, had to answer, and had to defer to their new partners. After all, the PE firm now owned them.

As the leadership team finalized the strategy in late October, the next set of questions from the PE guys arose. “So how are we going to pay people next year?” one of the sharp MBAs asked. Greg, the EVP of sales, knew his business, knew what had worked in the past, and knew what would work under the new strategy. “We’re increasing our account management focus and covering the white space in our accounts,” Greg said. “Placements and job orders are still important metrics, but profit contribution and service mix are going to point us in the right direction. I think we know what we need to do.”

Time was at a premium near year-end, so the leadership team took an expert approach to building the sales compensation plan that would support next year’s strategy. The sales organization hadn’t seen a new compensation plan in a couple of years, but the whole organization, from corner office to front line, was enthusiastic about their future prospects with their new partner and ready for change. Amid the December holidays, the leadership team worked on the plan during conference calls from their home offices, endured the additional rounds of great questions from the sharp MBAs, and finalized the plan.

Greg opened up the sales kickoff meeting in early January. He introduced Jim, who really needed no introduction. Jim laid out the plan for the year. Since he had started in sales in the industry years ago, Jim knew how to get a sales team amped up. This event was no exception. The sales organization was ready to go. But what the sales team really wanted to hear about was the new comp plan. The company’s new investors had brought fresh funding to the business, and everyone wanted to be part of the new vision. Greg’s presentation of the new sales compensation plan was concise and simple. But the plan itself, while smoothly articulated, wasn’t actually that simple. It aligned with all the pieces of the strategy, however, and the senior leadership team loved it. So did the PE guys. In the breakout groups that followed the comp plan presentation, the sales team had a few questions, but nothing major. The plan was done. The reps even had their quotas in January for the first time in a while, which, of course, they thought were too high.

Following the sales meeting, the organization got down to business. It was quiet for a while. Then, around mid-January, Greg received a few calls from the sales directors. By the end of January, the flow of calls started to pick up. Now the good questions were coming from the field rather than the PE firm. The questions were about the new sales compensation plan, the new measures, and the new mechanics. “Not that they’re bad,” the sales directors said, “but people aren’t connecting with the plan. We understand that it’s goal-based, but the reps aren’t sure what they’re earning, like they did with the old commission plan. And with that year-to-date quota measure, how should we explain how that compares to the old full-year quota attainment measure?”

The sales compensation plan was unraveling. The design wasn’t bad, but the preparation, communication, and implementation support just weren’t there. The sales team wanted the plan to work, but it was actually getting in the way of their work. The disconnection and confusion spread, and leadership began to panic. Within a quarter, the company had reverted back to its old compensation plan just to keep the troops in line. The old plan didn’t match the new strategy, but the leadership team thought it better to hobble through the year than to totally lose focus. They’d pick up the compensation plan challenge again for next year.

Unfortunately, this scenario occurs more often than it should. Leaders tell the sales organization how the plan works and then are baffled when the salespeople don’t understand. While most organizations concentrate on compensation plan design, additional focus on planning and making the change can make the difference as to whether the plan will pass or fail. A successful change process actually starts long before the change itself—at the inception of the idea. If an organization waits until the plan design is finished to begin communicating, they are starting from behind. Leadership may be preparing to communicate, but the organization is probably already talking about the impending change, and the sales leaders are not controlling the message.

Change Management Key Steps

Whether you are changing the sales compensation plan or making a change further upstream in the Revenue Roadmap, a change management plan with a heavy focus on communication will increase the likelihood of acceptance and mitigate confusion in the sales organization. Doug Holland, of ManpowerGroup North America, says, “If we’re making a big change that’s going to affect a lot of people, the first question our president will ask is, ‘Why? What is the rationale for the change?’ His sensitivity is, ‘What is it going to do for the performance in the field?’ He’ll say to me things like, ‘You know, Doug, if you present a compensation change for HR, marketing, finance, or IT, and it’s a bit disruptive, it’s not going to bother me. I understand that. But if you introduce a change that’s disruptive, in a bad way, in the field, that is going to bother me.’ That plan could be the greatest plan in the world. It almost doesn’t matter if people don’t understand it, if people don’t know how they’re going to grow their pay,” says Holland.

As in the example that opened this chapter, where the new sales compensation plan was not fully explained to the sales staff, it’s tempting to make one announcement or send out an e-mail describing the new plan and consider it done. But don’t assume anyone else will understand the new plan just because the people who designed the plan understand it. Real understanding—and the questions that pop up along the way from the end users—takes days, weeks, or sometimes months. Begin your change plan by looking at the entire process from evaluation, to plan inception, to design, to implementation. Put yourself in the shoes of the sales organization, concerned with their livelihood and any possible disruption, and develop your change plan to drive the strategy with the sales team in mind. When making your next change, consider the following six steps:

1. Start strong. Conduct your due diligence to make sure the program is bulletproof and ready to go.

2. Craft the change story. Be honest about the reasons for the change, and develop a clear message around the C-Level Goals.

3. See the organization’s view. Expect some resistance, and identify who those resisters might be so you can get them on board.

4. Get the change forecast. Know your organization’s readiness for the change and your team’s resolve to see it through.

5. Leverage the learning modes. Use multiple methods to communicate with the organization to increase the impact of your message.

6. Follow the process. Begin communication early and follow your approach until well after introduction.

Start Strong

Make sure you cover a few important checkpoints so the plan is ready for introduction. First, enlist the opinion leaders for input at the start of the process. Bring together not only executive stakeholders but also highly regarded representatives from the field who have a tactical operating view on the business. These opinion leaders can provide valuable input and help communicate the right messages to their peers.

Second, pressure-test the plan during the design phase. When the team has arrived at a good set of design drafts, expose the plan to a select group of managers or even top-performing reps for a cold look. This group could also include the opinion leaders. Pressure testing is most easily done in a small group setting or one-on-one. Ron Cox, former CEO of AchieveGlobal and Acclivus, believes in the importance of involving managers in the process. “I need to connect managers to the strategy and help them realize the important role that they’re playing in the company,” he says. “I have to get them working on the business, not just in the business.” The objectives are to get beyond the team to see how the end users will see the plan. Ask them to react to it, to describe how they think the organization might interpret it, and to try and outsmart it to find the loopholes or behaviors the company may not want to motivate. This process also gains additional buy-in from the group because they’ve taken a role in the plan design. The goal is not to negotiate with them or change the design on the fly but to gather intelligence as the plan is finalized.

Third, financially test the plan under a range of performance scenarios. Modeling at a high level by looking at target incentive, revenue, and cost of sales tells only part of the story. Payouts and cost of sales can vary dramatically depending upon the organization’s overall attainment of quota and how many reps attain quota. That’s because a sales compensation program often includes payout curves that reward at accelerated rates for high levels of achievement. It also incorporates multiple measures that may pay independently from the primary revenue measure. So, very simply, the organization could reach its goal in aggregate but pay more or less than the targeted cost of sales based on how the team reached its goal. If the team reaches its goal on average, but does it with a combination of very high and very low performers with few average performers, then the plan may trigger upside accelerators, increasing the cost of sale for those high performers, while low performers may not cover the cost of their base salaries—a perfect storm. Know every financial angle of your plan to minimize the potential for surprises.

Craft the Change Story

Looking back on the Revenue Roadmap and the C-Level Goals established at the beginning of the process can help the management team explain why they decided to change the sales compensation plan this year. Usually, the organization makes a plan adjustment if there is a change in sales strategy, a change in how the organization goes to market with its sales resources and sales process, a need to respond to a competitive situation, or if the plan simply isn’t doing what the organization intended and needs some adjustment or redesign.

The change story can be told in a variety of forms, including planned messages from leadership and informal hallway conversations. In any situation, the story should be concise, consistent, and positive. The storytellers, from CEO to first-line sales managers, should be well versed in the key messages and the range of possible questions. The components of the story include:

![]() Why the change is happening. Where is the organization now, and why is this change important?

Why the change is happening. Where is the organization now, and why is this change important?

![]() What is changing. Is it an overall change to the organization or a tactical change to a component of the sales compensation plan?

What is changing. Is it an overall change to the organization or a tactical change to a component of the sales compensation plan?

![]() Who will be affected. Will this impact certain groups or the organization overall?

Who will be affected. Will this impact certain groups or the organization overall?

![]() Where the change will take place. Is it happening in certain geographies first, or will it be introduced as a big bang?

Where the change will take place. Is it happening in certain geographies first, or will it be introduced as a big bang?

![]() When the change will take place. Will it happen this year? How long will it take?

When the change will take place. Will it happen this year? How long will it take?

To craft the change story, go back to the C-Level Goal areas of Customer, Product, Coverage, Financial, and Talent. Draw out the messages from each area that should be communicated to the sales organization and use them as the elements of the change story.

At CA Technologies, the CEO communicates the strategic vision to the entire company and then allows the sales compensation team to show how the new plan connects to his strategy. “The CEO gave us a platform upon which to make any of the changes we need to make: organizational, sales model, sales compensation. We were overly transparent against the strategy and the objectives. Then we as sales leaders could literally take that and run with it for changing the organization, and it worked beautiful, absolutely beautifully,” says BJ Schaknowski of CA Technologies.

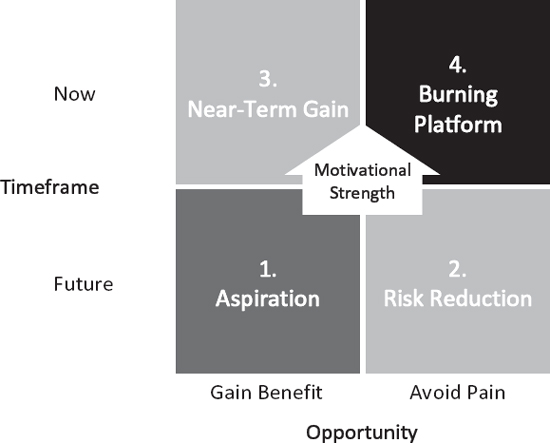

It’s human nature to resist change, so positioning your change story is key to moving the organization in the right direction. Think about how you might tell the story in one of four ways: aspiration, risk reduction, near-term gain, or burning platform. Each of these Motivators of Change can be described by its time-frame and orientation toward pain or gain, as shown in Figure 8-1. Many organizations want to communicate an aspirational story that excites the team about changing to capture future opportunities (quadrant one of Figure 8-1). A sales manager or sales rep hearing this message might find it worthwhile to be part of the dream as long as it’s within the not-too-distant-future and doesn’t require too much near-term sacrifice to her lifestyle.

FIGURE 8-1. MOTIVATORS OF CHANGE.

If a rep hears a story about avoiding risk or great pain in the future (quadrant two), that may capture a little more of her attention. For example, an executive a few years ago described her company’s situation to me, saying, “It’s all comfortable now, but our competitors are encroaching on us. We’re like the big ship in the harbor having a party, and all the little speedboats are coming in around us, and they’re going to eventually overtake and board us. People need to clearly understand where we’re heading on our current track.” Future risk can be more motivational than future vision alone if the organization can understand the eventual threat.

Gaining some benefit in a shorter timeframe (quadrant three) can be a positive motivator to make a change, especially if it’s tangible and achievable. If a rep can picture her family in a better position as her kids get to college age, she’s likely to be fully on board and to put in the hard work necessary to support the plan.

The greatest Motivator for Change, of course, is alleviating near-term pain with a burning platform approach (quadrant four). If the company has attempted to tell a quadrant two, risk reduction story and the organization hasn’t listened, events may have now transpired and the message now may be, “If we don’t make this happen by next year, this organization may have to downsize half of our people.” To a member of the sales organization, change doesn’t look quite as scary at that point because the alternatives are worse. In this case, the rep may not be fully on board but she’s also proactively looking for ways to help.

See the Organization’s View

Company culture plays a huge role in making change. Some cultures operate on stability and are naturally change-averse, while others are change-tolerant and even change-seeking. It’s important to know the organization’s and individuals’ comfort level with change in order to message and manage well.

Assume that most people will see any change as potentially negative. This is particularly true when it comes to compensation. From a sales organization view, unless the current compensation plan is a complete disaster, they often assume the only reason to change the plan is to manage pay or improve the company’s financial position. “If you have a sales program that allows people to make money, and you want to make a change to a compensation plan, you have to be crisp and clear about what those changes mean. Otherwise, the immediate thought process of a salesperson is, ‘They’re trying to figure out how to take money out of my family’s life,’ ” says Jeff Schmidt of BT Global Services.

Beyond risk, resistance also comes from reluctance to alter routines. If the new incentive plan steers the organization toward new products or perhaps selling to new customers beyond their current accounts, that can be plain uncomfortable.

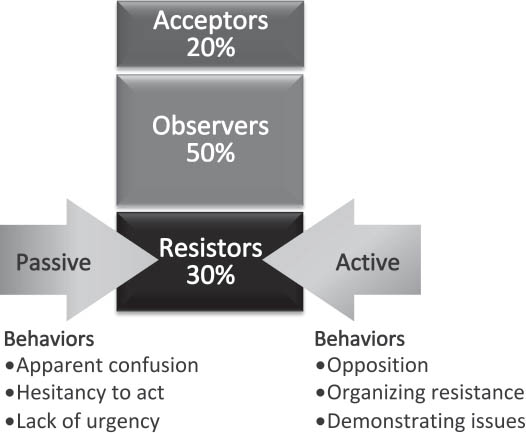

In our work, we see that about 20 percent of an organization are acceptors and embrace the new plan without argument. Another 50 percent are observers who will wait and see. If the plan is designed, communicated, and managed well, this group will usually join the first group of acceptors. But as much as 30 percent of the organization may resist the new plan. The resistors range from passive resistors to active resistors, as shown in Figure 8-2.

You may recognize some of the passive resistance behaviors, which include apparent confusion, hesitancy to act, and lack of urgency. On the aggressive side, behaviors might include outright opposition and involvement in trying to change the course of the implementation by demonstrating why the program will not work. The good news is that most resistors tend to be on the passive side, although they are not always easy to identify and engage. The key to working with passive resistors is to connect, sense, and communicate at the field level to understand their resistance points before the implementation. If ignored, their resistance can become contagious. As for active resistors, they’ll test leadership’s resolve for change, as we’ll describe shortly.

Get the Change Forecast

Most executives we work with can make a general statement about their culture’s comfort with change. When preparing for implementation, though, it helps to be a little more specific. By answering the following four questions, you will be able to get a forecast of the upcoming change. We recommend erring on the side of considering a change to be major rather than minor as it’s always safer to over-communicate.

1. What is the degree of change for the organization? If you’re implementing a change to a piece of the sales compensation plan—say, changing one performance measure—you may think of that as a minor change. If you’re implementing a new go-to-market strategy and the compensation plan change is part of that bigger change, you may think of that as transformational. Give your organization a score from 1 (minor change) to 10 (major transformation).

2. When was the last time your company changed the sales compensation plan? If you change the plan every year or two, you may call that a recent change. On the other end of the scale, the organization may not have changed the plan for 10 or more years. Give your organization a score of 1 (recently) to 10 (never).

3. What is the organization’s tolerance for change? Even if the organization hasn’t had a new sales compensation plan in years, its culture may be dynamic and trusting while it makes changes to adjust to the market. However, your organization may not sit well with change, even if it happens frequently. Give your organization a score of 1 (very high) to 10 (very low).

4. What is your management team’s resolve for change? While the sales organization has a tolerance for accepting change, the management team also has a resolve for making change. Test your resolve for when things get tough. Give your team a score of 1 (very high) to 10 (very low).

Your total score will give you a sense of your current environment, the likely near-term forecast for change, and potential actions you might take, as indicated in Figure 8-3.

Two companies we know illustrate a management team’s resolve for change with a range from Choppy Seas to Gale Winds. The first, a medical equipment company, had a low aversion to change but watched as competition in its market grew. The CSO told us, “We need to move this organization to a true sales culture and kill the environment of entitlement.” He went on to describe how they needed to make this happen and to explain that if they lost some people—presuming they were the right people to lose—it was okay. His team was determined to change. They pressed on and the new program made a huge difference for the company. They implemented the Reverse Robin Hood Principle (from Chapter 3) and their growth rate moved back into double digits. They used a change story that included their near-term pain (quadrant four, the burning platform quadrant of Figure 8-1) and moving toward their future opportunity (quadrant one) at the same time.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, an industrial manufacturing company was more averse to change and was struggling with being “commoditized” by overseas competitors with lower manufacturing costs. There, the CSO called the front-line reps “his kids” and told us, “No matter what we do, everyone needs to be comfortable. We must take care of everyone.” It was a very family-oriented culture. The CSO and his team had less resolve to push through on change, which slowed the process for them.

If the forecast is Gale Winds to Potential Storm, a company going through a significant change will probably meet active resistors (described earlier), who can potentially derail the initiative. However, if the management team is determined to make the change and the company has an executive in place who has created a clear mandate for change, using the velvet hammer can actually smooth the process.

A Fortune 500 business services company we worked with went through a major change a few years ago. The company had acquired a number of other companies, and the integration included a change in go-to-market strategy and a new incentive program. It was a positive step for the organization with lots of potential—a healthy quadrant one and quadrant three change story. But they had adamant resistors in some of the old guard in the acquired organizations. The resistors were in leadership positions; because of their ownership stakes in the acquired companies, they did very well financially. But when it came to making change, they did everything in their power to keep things the way they were. After a period of time, this active resistance started to create stress on the organization, which could have jeopardized the company’s success. One day, the C-level’s velvet hammer quietly came out, and the resistors just disappeared. It was a strong message that was reserved only for an extreme situation, but it ultimately enabled the organization and its shareholders to realize the benefits of a successful change.

Leverage the Learning Modes

Simply announcing the new program or distributing plan documents may get the message across to some, but it is certain to miss others. While developing your communications plan, incorporate a few learning modes that will connect with the range of people in your organization. As proposed in the Theory of Multiple Intelligences by Harvard psychologist and Professor of Education Howard Gardner, there are at least seven modes you can leverage using a range of communications vehicles. Here are examples of some of the learning modes and how you might use them with the sales compensation plan.

1. Linguistic learners capture information through language, both in writing and orally. They learn by reading, listening, and telling stories. For the sales compensation plan, leverage written communications and conversations in individual and group formats.

2. Logical-mathematical learners have the ability to see relationships between objects and solve analytical problems. They’ll be the first to backward-engineer the new plan. For the compensation plan, leverage plan calculators and examples and be clear on comparisons to the prior plan.

3. Visual learners have high visual intelligence and can translate information easily to and from images and pictures. For the compensation plan, leverage visual models of how the components work.

4. Kinesthetic learners absorb new information through touch, manipulation, and movement. For the compensation plan, leverage demonstrations and role plays of how the plan works.

5. Musical learners recognize tones, rhythms, and musical patterns and can often remember and repeat a melody after listening it to once. For the compensation plan, leverage messaging and phrases to reinforce the message. One client coined the term “55 to stay alive” as it introduced a new program, while it operated in quadrant four of the Motivators of Change.

6. Interpersonal learners connect with people, have the ability to influence people, and are often natural leaders. For the compensation plan, leverage one-on-one and small group communications and enlist them as supporters of the plan in the field.

7. Intrapersonal learners are keenly aware of their strengths and weaknesses and have great self-discipline. They sometimes prefer to study individually. For the compensation plan, leverage messages about personal growth and allow time to absorb and process new information before following up.

Follow the Process

As you’ve worked through the steps of starting strong, crafting your change story, seeing the organization’s view, and getting the change forecast, you’ve covered a number of major steps in the change process. These began during the inception of the incentive plan design and continued through the program assessment and program design, as shown in Figure 8-4.

During the program assessment phase, use a regular flow of inbound and outbound communication between the leadership team and the sales organization. This communication includes the initial C-level announcement, input from stakeholders and the organization, and regular updates to the organization on the initiative. During program design phase, pressure-test the plan with opinion leaders and prepare the change story within the context of the organization’s change environment. As the organization moves closer to implementation, there are several communications points that should be covered using a selection of tools, including incentive plan documents, introductory presentations, key message scripts, and frequently asked questions to keep the team consistent and on-message.

FIGURE 8-4. COMMUNICATIONS POINTS.

In the implementation phase, pre-launch, assuage the people who may be affected. In any change, team members will be affected in both positive and negative ways. Since a plan design can be developed for each person, address highly valued team members who may be negatively impacted by the change to explain the impact of the change and, if necessary, work out transition plans to get them successfully through the change. Of course, this process should start during program assessment and design through a process of socializing the upcoming change with the organization. At the pre-launch point, these changes should be a formality for highly valued team members so they’re on board with the change and are advocates of the change.

On Day1, announce with strategic themes and reinforce at the team level. Make the plan announcement within the context of the overall sales strategy. This is the first formal communication of the change story. It should hit on all the C-Level Goals and be positioned with the right Motivators of Change given the environment. Translate the story to the team through sales management in concert with the strategic announcement. Sales management should then work with the team in breakout groups that get into the details of the program, answering questions and making sure that each member of the organization understands the new program.

In the first 14 days following the announcement, open the communications channels. To support the announcement, open up your support channels to capture the inevitable inbound questions and manage the flow of communications. These vehicles typically include an inbound voice hotline, a dedicated e-mail account, a company-operated blog, and social media presence. While some of these vehicles may seem nontraditional, it’s not uncommon for the sales organization to establish its own web and social media presence in response to a major change. It’s usually better for the company to move proactively in this direction than to reactively defend.

Thirty days after the announcement, test for understanding. No matter how well accepted the plan is during the announcement, don’t assume the whole organization understands it. Following the announcement, managers should work on a schedule to reach out to reps and confirm their understanding of the plan and their objectives.

Sixty days after the announcement, test for behavior change. The first sign that the plan is beginning to work is a pattern of behaviors that are consistent with the objectives of the program. Test for these changes through direct coaching and observation by sales managers and through performance measurement with vehicles like the CRM system that track activities and steps in the sales process.

Ninety days after the announcement, test for results. At the 90-day point, test for performance results under the new plan. Depending upon the length of the sales cycle, results may begin to show during the initial months or after the first quarter. With many implementations, the sales organization can actually experience a dip in performance after the introduction as it adjusts from any initial distractions and begins a new, consistent rhythm.

Quarterly, evaluate behaviors and results. At quarterly points, assess the performance of the plan and whether it’s continuing to deliver the desired behaviors and results. A monthly view can provide more granularity as long as those shorter periods give a reliable reading on results without spikes in performance. As the organization moves into a couple of iterations of the quarterly evaluation cycle, it can also begin to assess the plan’s ability to support the strategy for the upcoming year.

When making the change to your program, start early with socialization, craft the right story for your change environment, and stay sensitive to the organization while you work through your multimode communications process.

5 QUESTIONS YOU SHOULD ASK YOUR TEAM ABOUT MAKING CHANGE

1. What is our message and story about the change?

2. Is our organization ready for change, and does our team have the resolve to manage it?

3. What modes of communication will we use to connect with each facet of our audience?

4. How should executives and sales management lead and reinforce during implementation?

5. What is our plan to sense the organization and make course corrections if necessary?