2

AGILITY: RIGOR WITHOUT RIGIDITY

“Success today requires the agility and drive to constantly, rethink, reinvigorate, react, and reinvent.”

Bill Gates

A 100‐year‐old iconic company admired for decades as the most innovative company in diverse industries from automotive to electronics, healthcare, and consumer products appoints a new CEO in 2000. His focus is on execution and operational efficiencies as he implements Six Sigma to streamline work processes and focus on cost efficiency and quality control. The company was 3M, well‐known for innovations like Scotch tape and Post‐it notes. What do you think would be the impact of process rigidity on an innovative company like 3M?

While there were efficiency gains and operating margins grew from 17 percent to 23 percent, there was a dramatic fall in the number of innovative products developed in those years. According to Fast Company magazine, 3M fell from number 1 in 2004 to number 7 on the most innovative companies list. James McNerney, the CEO of 3M from 2000 to 2005 applied Six Sigma across the board. Six Sigma is process heavy and aims to remove variability to avoid errors and increase predictability. Developed at Motorola, Six Sigma was adapted by Fortune companies like GE, Honeywell, and many others in the 1990s. Processes like Six Sigma are about consistency and control and work well in a mechanical world, whereas the DANCE and disruption are characteristic of difference, failure, disorder, learning, and mutation.

Project management and PMOs face a similar challenge as they are perceived as top‐down, controlling, and bureaucratic, stifling innovation in an increasingly DANCE and disruptive world. On the other end of the extreme, there are start‐ups and companies with very little or no process, and chaotic, free‐for‐all cultures with no boundaries and constantly shifting focus. Any management process, whether it is Six Sigma or project management or project management office (PMO), can be beneficial, but the challenge is knowing how much is right for your organization and business. Failure stems from either too much or too little governance and process. The challenge is that to thrive, you need to find your sweet spot between the two extremes.

In his book, Seeing What Others Don't: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insight, cognitive psychologist Gary Klein argues:

Organizations are preventing insights by imposing too many controls and procedures in order to reduce or eliminate errors. Organizations value predictability and abhor mistakes. That's why they impose management controls that stifle insights. If organizations truly want to foster innovation and increase discoveries, their best strategy is to cut back on the practices that interfere with insights, but that will be very difficult for them to do. Organizations are afraid of the unpredictable and disruptive properties of insights and are afraid to loosen their grip on the control strategies.

In this chapter, we address the question of how to achieve true agility by finding your sweet spot between the two extremes. It is important to prepare the right operating system before we delve into decoding and developing the DNA of strategy execution for project management and PMO practices.

HOW TO REFRAME THE ORGANIZATIONAL OPERATING SYSTEM AND MINDSET

“The most common source of management mistakes is not the failure to find the right answers. It is the failure to ask the right questions …. Nothing is more dangerous in business than the right answer to the wrong question.

Peter Drucker

The next generation depends on questions. In the past, we relied on answers, but in today's world as the DANCE intensifies and uncertainty increases, the value of questions goes up, and the value of answers goes down. It is harder to understand the problem than to have answers that are no longer relevant. How can you expect different outcomes with the same questions? The challenge is to learn to ask better questions. While solutions tend to converge and pacify, questions have the opposite effect. They agitate and cultivate a mindset for agility, constantly challenging the status‐quo, seeking diverging perspectives, and pushing to the edge. To better prepare for the DANCE and disruption, you have to reframe the organizational mindset and create a culture of inquiry. Questions are like lenses that provide a multiplicity of perspectives and unlock new doors.

The PMO can take a leading role in fostering a question‐based culture across the organization by holding up the mirror and reflecting the right questions in a multidisciplinary way, bridging silos and reconnecting different aspects of the DNA of strategy execution. Traditional project management and PMOs are typically focused on finding answers and providing solutions for execution. The next‐generation PMO should start by challenging if you are working on the right problems and projects by using different questioning techniques.

In our next‐generation PMO seminars, we start with a question‐storming exercise. It is a divergent process designed to come up with a multiplicity of perspectives with the power of questions, as opposed to brainstorming, which is convergent honing on multiple solutions to one problem. Hal Gregersen, executive director of the MIT Leadership Center and senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School, explains:

Regular brainstorming for ideas often hits a wall because we only have so many ideas. And the reason we hit that wall is we're asking the wrong questions …. It's perfect to step back and say: Okay, question storming time. And what do I mean by that? If I'm with the team: Grab a flip chart. Have someone be the scribe and have the team generate at least 50 questions about the problem that we're stuck on. Number those questions. Write them down up there, when they are being written down other team members are paying attention and thinking of a better question. Do it again and again and again. But what we discover is that when people then step back and do that kind of question storming, list a long series of questions and they do it collectively where they can see the questions and generate new ones, it actually gets them closer to the right question that will give them the right answer. And that's where question storming compliments traditional brainstorming.

Hal has developed a methodology—catalytic questioning, an alternative to traditional brainstorming—business leaders can use to drive change in their lives, workplaces, and communities. It takes just five simple steps:

- Gather employees around a writing surface.

- Choose the right problem.

- Engage in pure question talk.

- Identify the “catalytic” questions (questions that hold the most potential for disrupting the status quo). Focus on a few questions that your team honestly can't answer but is ready and willing to investigate. Winnow your questions down to three or four that truly matter.

- Find a solution.

Question storming is also referred to as Q‐storming by Marilee Adams, in her book Change Your Questions, Change Your Life. She elaborates that the goal in Q‐storming is to generate as many questions as possible. The expectation is that some of these questions will provide desired new openings or directions. Typically, questions open thinking, while answers often close thinking. Q‐storming is based on three premises: (1) great results begin with great questions; (2) most any problem can be solved with enough of the right questions; and (3) the questions we ask ourselves often provide the most fruitful openings for new thinking and possibilities.

In the Q‐storming exercise, groups of stakeholders start with what questions we need to ask for the PMO to provide greater value to the organization, or what questions we should be asking to take the PMO to the next level.

Table 2.1 is an unedited Q‐storm from one of our PMO facilitation workshops.

Table 2.1: Sample Q‐Storm of what we need to do to take the PMO to the next level

| What is the need for the PMO? What if we did not have a PMO? What should PMO stop doing? Why do people not like us? What pain are we causing? How do we define PMO success? How will we measure success? Are we measuring the right things? What processes should be improved? What tools are right for us? How do we keep the PMO relevant? How do we measure PMO value and return on investment (ROI)? Who are our customers? What are we doing well? What are we not doing well? What are our organization's pain points? What can we adapt from other successful PMOs? What does failure smell like? Do we have the right resources? What environmental factors influence us? |

What's our appetite for change? How will we get feedback from our customers? How should we train our resources? What PMO model is right for us? How will we ensure we're aligned with overall biz strategy? What is the overhead on our projects? How do we put structure in place but remain flexible? How do we evolve as the organization changes? What do our customers value? How do we market ourselves? How can we gain the support we need from different stakeholders? If we started from scratch, how would we go about it? How can we drive the right behaviors? What is our impact on people? How are we changing how people feel about performing their jobs? What does an ideal PMO look like? What is the pain that the PMO should address? Why do projects fail? What do customers want? How do we prioritize what we need to do? |

What is the right org structure for the PMO? What support do we have and need? Who are the most influential and key players? How do we say “no” and make it stick? What will make project managers happy? What behavior do we want to encourage? What authority does the PMO have? Are we clear on our business strategy? How do we engage and get people excited about project management? How do we identify and reduce disconnects? How can we make ourselves invaluable? What relationships do we need to build? Are we listening? Do we know what our capacity is? Are we moving the needle? Are we stuck in status quo? What should be the roadmap for the PMO? What roadblocks and dependencies do we see coming? How do we develop and retain talent? How can we connect and communicate better? |

After a Q‐storming exercise, we typically hear comments like, “This was an eye‐opener … we didn't know we had to think about all these things … before I came to this session, my focus was so narrow … now we know we are not even thinking about the right things.…”

Project managers and PMOs must shift from a fixation on the solution toward learning to ask better questions that help reframe the problem and provide a different point of view and open new doors. The questioning approach will raise the quality of planning, risk management, and surfacing assumptions, among other things. Questioning is an art and skill that has to be learned and developed. Table 2.2 shows sample questioning techniques compiled from different sources.

Table 2.2: Sample Questioning Techniques

| Technique | Description | When to Use |

| Five Whys [Toyota] |

Investigative method of asking the question “Why?” five times to understand what has happened (the root cause). Each question forms the basis of the next question. The technique was formally developed by Sakichi Toyoda and was used within the Toyota Motor Corporation during the evolution of its manufacturing methodologies. The tool has seen widespread use beyond Toyota and is now used within Kaizen, lean manufacturing, and Six Sigma. |

To explore the cause‐and‐effect relationships underlying a particular problem. To shift your perspective and point of view—helps in re‐framing problems. |

| Why–What If–How [Warren Berger] |

A framework designed to help guide one through various stages of inquiry—because ambitious, catalytic questioning tends to follow a logical progression, one that often starts with stepping back and seeing things differently and ends with taking action on a particular question. | A model for forming and tackling big, beautiful questions that can lead to tangible results and change. |

| How Might We [Min Basadur/Sydney Parnes] |

The specific form of questioning with the words “how might we” designed to spark creative thinking and freewheeling collaboration. By substituting the word might instead of can or should, you are able to defer judgment, which helps people to create options more freely and opens up more possibilities. This technique is also extensively used at IDEO. Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, explains, “The how part assumes there are solutions out there—it provides creative confidence. Might says, we can put ideas out there that might work or might not—either way; it's okay. And the we part says we're going to do it together and build on each other's ideas.” |

For creative problem solving and generating multiple options and possibilities. |

| Propelling Questions and Can‐If [Adam Morgan and Mark Barden] |

A propelling question is one that has both a bold ambition and a significant constraint linked together. It is called a propelling question because the presence of those two different elements together in the same question does not allow it to be answered in the way we have answered previous questions; it propels us off the path on which we have become dependent. For example: How do we win the race with a car that is no faster than anyone else's? (Audi) How do we build a well‐designed, durable table for five euros? (IKEA) Shift from We Can't Because … to We Can‐if … to instill a sense of how something could be possible, rather than whether it would be possible. |

To achieve a bold ambition, but with a significant constraint that helps to break path dependence, and spur entirely new kinds of solutions. For constraint‐driven innovation. |

| Then What [Warren Buffett] |

To elicit consequences—whenever someone makes an assertion to you, ask, “And then what?” According to Warren Buffett, “Actually, it's not such a bad idea to ask it about everything. But you should always ask, “And then what?” | To help drive focus on consequences. |

| What Must Be True [Roger Martin] |

To specify what would have to be true for the option or choice to be right. Can be used as a collaborative approach to surface the assumptions and understand the convincing logic of the options. | To surface an assumption and turn it into an advantage. |

| If‐Then | To highlight any conditions that need to exist to achieve outcomes—dependencies, interfaces, policy considerations, resources, market factors, and other important conditions to make if‐then logic valid. | To communicate project plans, progress reports, and expected results or outcomes. To highlight critical assumptions and risk factors. |

Throughout the book, we will be using questions to open new doors and keep seeking new insights to develop intelligence in each of the elements of the DNA.

“I would rather have questions that can't be answered than answers which can't be questioned.”

Richard Feynman

One of the questions to start with is why half of PMOs are not perceived as successful? According to the Project Management Institute's Pulse of the Profession, 2017, 71 percent of organizations have a PMO, up from 61 percent in 2007. Even though PMOs have become a common organizational fixture in many organizations, the success rate has not gone up. According to Projectize Group's survey‐based PMO research (2005–2017), 52 percent of PMOs are not perceived as successful by key PMO stakeholders. 39 percent responded that the relevance or existence of their PMOs has been seriously questioned. These findings are echoed by other reports from various organizations over the years, including a multiyear PMO study by Brian Hobbs and Monique Aubrey, PMO: A Quest for Understanding.

Often, you learn more from questioning why something doesn't work than from why it does. One of the exercises we conduct in our practice is to ask the key stakeholders an important question: What can you do in your PMO to ensure it does not succeed? This is backward thinking, a technique, explained by Peter Bevlin, in his book Seeking Wisdom. Instead of asking how we can achieve a goal, we ask the opposite question: What don't I want to achieve (non‐goal)? What causes the non‐goal? How can I avoid that? What do I now want to achieve? How can I do that?

What can you do in your PMO to ensure it does not succeed? (non‐goal)

Typical responses we see listed are …

- Don't communicate the purpose of the PMO

- Disconnect between strategy and execution

- Lack of business understanding and focus

- Require too many mandated bureaucratic processes

- Don't explain why they have to follow PMO processes

- No training or support

- Don't define roles/responsibility clearly

- Inflexibility and one‐size‐fits‐all policies

- Not addressing the current needs and pain points of the organization

- Set high expectations and unachievable goals

- Punish people for not following processes

- Reward bad behaviors

- Don't pay attention to organizational culture or politics

- Don't plan for organizational change management

- Lack of stakeholder and customer engagement

- Don't care or plan for stakeholder buy‐in for the PMO

- Stumbling block for new ideas and innovation

- Slow down agility

- Lack of understanding of reality of DANCE and disruption

An interesting outcome of this exercise is that, invariably, it surfaces the following top reasons why organizational project management or PMOs fail:

- Unclear purpose

- No buy‐in

- Perception of more red tape, bureaucracy, and overhead

- Quick‐fix to deep‐rooted problems

- Project management policing

- Too academic and far from reality—professionalism and quality for its own sake

- Veneer of participation and hidden agendas

- Politics and power struggles

- High expectations and fuzzy focus

- Hard to prove value

The preceding reasons are prevalent because traditional approaches are skewed toward a top‐down, controlling, policing, rigid, and bureaucratic project management and PMO based on a mechanical mindset. They do not recognize the DANCE and are unaware that they are playing a different game, which requires a different approach as discussed in the first chapter. It is important to understand fundamental distinctions between traditional or foundational approaches, and evolving start‐up, organic, and agile approaches.

DISTINGUISHING TRADITIONAL VERSUS EVOLVING APPROACHES

Figure 2.1 highlights the distinctions between foundational/traditional versus evolving/agile/adaptive organizational and PMO approaches. You can check either one of the characteristics and add the number of your checks at the bottom to get a score that will highlight whether you lean more toward traditional/foundational or evolving/agile.

| Foundational/Traditional | Evolving/Adaptive |

| Mechanical or Factory mindset (machine‐oriented) | Organic mindset (knowledge‐oriented – non‐linear & connected) |

| Focus mostly on execution and delivery | Focus on strategic decision support, business value, end‐user & customer experience |

| Focus on science of management (technical expertise) | Focus on art and craft of management (organizational savvy) |

| Emphasis on monitoring and control | Emphasis on support and collaboration |

| Provides tools similar to a precise “map” to follow | Provides tools similar to a “compass” that show the direction |

| Rigid and formal structure, process, and governance standards, methods and processes (one‐size fits all) | Responsive, flexible and flat structure, agile governance methods and processes (context dependent) |

| Extrinsic approach: Top‐down, chartered, selected, outlined | Intrinsic approach: Evoke, provoke, encourage creativity, experimentation & learning |

| Process driven: Focus on process & methodology compliance | Customer & business driven: Focus on value, experience, & impact |

| Emphasis on rules; follow rules | Based on guiding principles; Follow rules and improvise if needed |

| Seek stability & global consistency | Seek agility and innovation |

| Focus on the “WHAT” (task management) | Focus on “Why” & “WHO” (stakeholder/relationship management) |

| Focus on efficiency: Manage inputs & outputs | Focus on effectiveness & experience: Ownership of results & outcomes |

| Exploitation | Exploration |

| Measure & track compliance; certification & delivery | Measure & track benefits, value, experience, & impact |

| Foundational/Traditional Score = ? | Evolving/Adaptive Score = ? |

Figure 2.1: Traditional versus Evolving Approaches

Source: © J. Duggal. Projectize Group.

Figure 2.1 highlights the fundamentally different approaches to setting‐up and managing organizations, based on a mechanistic view of foundational or traditional aspects of standards, stability, and rigidity versus flexibility, agility, and responsiveness in the evolving, organic mindset. On the one hand, there is a need to establish rigor with a sound governance structure of methods and processes; on the other hand, there is a demand for freedom and flexibility. This is indeed a primal paradox between the need for discipline and freedom at the same time. This dilemma hounds the successful implementation of project management and PMO processes. It surfaces the underlying friction and challenges long‐questioned beliefs about control and the role of management. To bring about the discipline, you need the rigor of standards and processes. However, the rigor can turn into rigidity that restricts judgment and stifles creativity and tend to slow and restrain organizational agility and innovation.

The distinction also highlights false assumptions that are inherent that the right side is better than the traditional approaches of the left side, or vice versa. For example, start‐ups can move and pivot with speed and agility, or established companies have consistency and predictability. After a certain point, start‐ups struggle to maintain momentum, lose focus and become chaotic, while traditional companies become bureaucratic and rigid that hamper their ability to move. Traditionally, the purpose of PMOs is to implement standards and processes and are more skewed toward the left.

Another assumption is that executives have to make a trade‐off and choose between one or the other, speed and agility, or standards and stability. The classic mistake is to treat it as an “either/or” choice, instead of “and/both” thinking that can identify links between opposing forces and generate new ideas. To practice this, you have to understand integrative thinking and apply the power of paradoxical frames. Roger Martin, in his book The Opposable Mind, defines integrative thinking as “the ability to face constructively the tension of opposing ideas and, instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generate a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new idea that contains elements of the opposing ideas but is superior to each.” By acknowledging and combining the opposing elements, you temper the undesirable side effects of each element and enable new insights that integrate both elements.

Stanford professor Charles O'Reilly explains organizational ambidexterity as,

the ability of an organization to compete in mature markets and technologies—where key success factors involve efficiency, incremental improvement and short timeframes; and simultaneously, to compete in emerging markets and technologies—where key success factors require flexibility, initiative, risk‐taking and experimentation. Research indicates that the ability to do both of these at once is associated with long‐term success.

WHAT IS NEXT‐GENERATION PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND PMO?

Next‐generation project management and PMO is ambidextrous; it recognizes the importance of both the elements and does not focus on either/or. It acknowledges the tension between the paradoxical elements but understands that marrying the two reduces the undesirable effects of each and leads to new insights and blended solutions. For example, make sure everything is planned for the go‐live, but also remain flexible so that we can deal with last‐minute requests from customers. This is a classic paradox that stumbles traditional PMOs, who do not recognize how planning and flexibility can positively reinforce each other. Continuous planning can help you be better prepared for customer changes and enable greater flexibility.

The next‐generation PM and PMO is better prepared to deal with the DANCE and disruption because it pushes strategy execution to the edge, by constantly questioning, seeking, and learning. It learns how to juxtapose the opposing forces of the need for rigor and flexibility and use them to create a dynamic strategy execution environment. Next‐generation PM has to use a bimodal approach or barbell strategy. Nassim Taleb, in his book, Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, describes the barbell strategy by explaining that the barbell is meant to illustrate the idea of a combination of extremes to describe a dual attitude of playing it safe in some areas and taking a lot of small risks in others. Extreme risk aversion on one side, and extreme risk loving on the other, thus reducing the downside risk of ruin, while capitalizing on the positive risks. You can't plan for the unpredictable, but you can build shock absorbers, and increase absorptive capacity, by embracing and capitalizing on the paradoxes.

Which Quadrant Is Your Organization in Today?

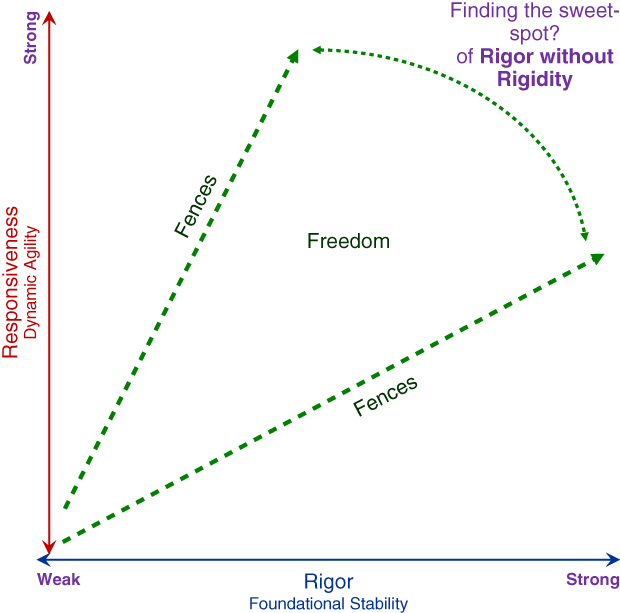

In Figure 2.2, the rigor versus responsiveness matrix lists the characteristics of each quadrant from the two extremes of bureaucratic and start‐up environments to the balanced next generation. Check each box that relates to your organization. Add the number of checks in each quadrant to determine where your company is today.

Figure 2.2: Rigor vs. Responsiveness

Source: © J. Duggal. Projectize Group.

Rigidity can be defined by a heavy emphasis on formal structures and control, standard methods and processes, top‐down governance with dictated authority, responsibility, and decision making. You are expected to follow precisely defined rules and procedures rather than to use personal judgment. In contrast, responsiveness means the project management practices or the PMO is responsive to the stakeholder and business needs. It emphasizes flexibility, adaptable and customized processes, and self‐regulating governance with shared authority, responsibility, and decision making. A responsive PMO is tuned to the shifting business environment and can respond to changing priorities. For example, you may have worked hard to come up with a consistent project selection criteria model, but a responsive PMO would be open to adjusting and fine‐tuning the model rather than stubbornly proposing a one‐size‐fits‐all approach.

Typically, the idea of project management methodologies and PMOs conjures up images of bureaucracy and loads of unnecessary paperwork. In the Projectize Group survey referenced earlier, 72 percent of PMO stakeholders perceived their PMOs to be bureaucratic. Indeed, project management methodologies and PMO practices are often guilty of inflicting too much process, like requiring your project managers to complete two weeks of project documentation on a one‐week project. It is akin to installing an elaborate security system on a cookie jar with a detailed process for removing cookies to prevent your child from eating too much sugar.

The traditional notion of control and mandated compliance can be an illusion. You may think you are gaining control, but what you are getting is paperwork and bureaucracy, while project managers and team members seek ways to undermine the processes. They may fill out the forms and templates to the letter to get the PMO off their backs, but not necessarily with the right spirit. Whether you are trying to bring up your child in a disciplined environment or you are trying to implement the discipline of project management practices, you go through a similar struggle. To bring about the discipline, you need the rigor of standards and processes. However, the rigor can turn into rigidity that restricts agility.

How to Achieve Balance

3M did manage to regain its groove. In July 2005 a new CEO, George Buckley, was appointed. He worked to preserve the benefits of Six Sigma's cost‐cutting and efficiency‐improvement efforts while simultaneously re‐stimulating the creative and innovative juices at 3M. The way he managed to find the sweet spot was to exempt a lot of the research process from the more formal Six Sigma forms and reports. He found a way to balance by having process rigor where it made sense and toning it down in other areas. According to Buckley, “Invention is by its very nature a disorderly process …. You can't put a Six Sigma process into that area and say, well, I'm getting behind on invention, so I'm going to schedule myself for three good ideas on Wednesday and two on Friday. That's not how creativity works.” By 2010, 3M had restored its innovative edge, and since 2010 it has continuously made it to the top 10 in Strategy & PwC's top innovator's list.

The need for rigor and freedom are opposing forces that cause friction between the PMO and its stakeholders. You have to seek the balance between the extremes of rigidity and responsiveness to varying degrees, as illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: How to Achieve Balance

Source: © J. Duggal. Projectize Group.

The very purpose of implementing project management and PMOs is to achieve discipline. Either extreme, rigid processes or flexibility with no standards, is not desirable. It is imperative to optimize the balance between two forces inherently at cross purpose.

As Peter Drucker said, “Most of what we call management consists of making it difficult for people to get their work done.” The opportunity is to find the balance that makes the PMO responsive to the needs of the stakeholders, so it is easier for them to manage projects. For example, the PMO has to target the right mix of rules versus guidelines, instead of strictly defined “Ten Commandments,” the PMO may require “Four Commandments and Six Suggestions.”

Finding Your Sweet Spot

Use the rigor without rigidity figure to create a matrix and identify which quadrant your PMO is in. The next step is to identify the structures, standards, processes, and rules that are the backbone and required and have no leeway for flexibility. Each of the remaining processes should be adjusted toward responsiveness to create more dynamic processes that can adapt to changes and opportunities. Think about agile values of individuals and interactions over process, working software and products over documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiations, and responding to change over following a plan, as you try to achieve balance. The appropriate location on the matrix will depend on a number of factors, including:

- Business. The nature and criticality of business dictate the level of rigidity required. For example, a hospital or a nuclear power plant might have a more urgent need to establish standard policies and procedures than a consulting company.

- Content. The content and relevant importance of processes, policies, and procedures determine which side of the grid they may lean toward. For example, security and privacy processes or project budget governance should be more rigid than configuration management.

- Scope. The extent of rigor should be determined by the scope of the project. It is a good idea to define project classification criteria that helps to classify projects into simple, medium, and complex categories. For example, a simple project may need very limited process steps versus a complex project that may require more elaborate methodology steps.

- Culture. More methodology implementations flounder from failing to adequately account for an organization's cultural factors than for any other reason. A culture's level of receptivity to change can make or break any effort to make improvements or achieve compliance. For example, it is easier to implement a project management methodology in a control‐oriented culture versus a cultivation‐oriented innovation culture where people abhor standards and processes.

- Maturity. The receptiveness to processes depends on the overall organizational maturity of project management practices. Maturity will be based on the availability, quality, training, and support of the methods and processes that are provided. The greater the maturity chances, the better understanding and greater appreciation of the real intent of the processes and the greater the effort toward balance and voluntary compliance will be.

It should also be noted that over time the sweet spot may shift to varying degrees on the grid. This is why it is important to regularly rethink and redesign governance and related processes to strike a balance and achieve rigor without rigidity.

A PMO team from a U.S. multinational company expressed how excited they were a year ago when management had finally approved an enterprise PMO to work with the local and regional PMOs to establish global standards and procedures. The global PMO team worked hard in rolling out a project management methodology and standard templates with detailed procedures and mandated requirements. However, after a few months of completing their rollout, they were frustrated and could not understand why they were getting resistance and limited compliance.

Another PMO team of a global financial services company deployed a worldwide project management training program. It involved weekly global conference calls, pilots, and feedback sessions from the various regional PMOs. The rollout was well received, and regional PMOs were eager to adapt and embrace project management.

Why were the outcomes for the two rollouts so different?

The answer has much to do with the different approaches taken by the respective teams. The team in the second scenario made sure that all the regional and local PMO representatives were involved in the rollout. They familiarized themselves with the local cultural, organizational, and procedural idiosyncrasies. They were responsive to local needs and maintained a careful balance between the need for standards and flexibility.

Cultivating a Studio

Imagine if you could cultivate a culture like a young start‐up where people are excited, they have skin in the game, and they want to come and play in the sandbox, not because they are forced to but because they want to. Of course, it is easier said than done; the question is, what should this sandbox look like and how do we define the boundaries to achieve the right balance? An example is to think of the idea of Freedom with Fences, an informal motto that has been made popular at Harley‐Davidson. It enables employees to understand both the limits and the latitude they have to make improvements in their work processes. Project managers and teams are like artists who collaborate in a studio and treat each situation as unique and use personal judgment and creativity rather than relying on rote processes for every situation.

Typically, PMOs spend a lot of time building fences of rules, restrictions, forms, mandated processes, and methods as defense and control mechanisms, albeit with good intentions to achieve standardization and consistency. But these fences tend to go overboard and suffocate people and stifle judgment and creativity. Studios or sandboxes, by comparison, provide the platform for artistic freedom that can spark creativity and innovation.

Forced Compliance versus Voluntary Compliance and Commitment

In our experience in implementing project management practices and PMOs, we observe a clear contrast in the behavioral effects of the two opposing approaches of forced compliance in rigid environments, versus voluntary compliance and commitment in responsive environments. Table 2.3 highlights the differences and provides a list of desirable characteristics to strive for.

Table 2.3: Forced Compliance versus Voluntary Compliance and Commitment

| Forced Compliance | Voluntary Compliance and Commitment |

| Follow methods and processes to the letter | Follow methods and processes in the spirit |

| Minimal compliance with expectations | Exceed expectations |

| Aggravation and annoyance | Inspiring and energizing |

| Excuses and avoidance | Passion and commitment |

| Blame and finger pointing | Ownership and responsibility |

| Prescriptive answers and recipes | Insightful questions and inquiry |

| Restrictive and stifling | Enabling and creative |

| Hidden agendas, sabotage, passive aggressive | Uncompromising dialog, problem solving, and negotiation |

| Take advantage of established measures and metrics | Strive for meaningful measures and metrics |

| Controlling and constricting culture | Freedom and responsibility culture |

HOW TO DESIGN EFFECTIVE BOUNDARIES

An oft‐used cliché is that managing people or stakeholders is like herding sheep; the challenge is, how do you corral the sheep in such a way that you steer them in the direction you want them to go effortlessly? The answer lies in how you design the field to your advantage by focusing on cultivating a conducive environment and tilting it to your advantage, so people comply because they want to and not because they are forced to. While implementing project management practices, the fences of processes and methods should be developed and raised collaboratively as much as possible. They should be permeable and flexible with built‐in mechanisms for feedback. And, of course, they should provide enough freedom for personal judgment, creativity, and innovation. The PMO should cultivate a culture where it is OK to bend but not break the rules to be agile.

Fair Process and Procedural Justice

People will respect the rules and boundaries of the fences if they believe it was a fair process. The idea of fair process and procedural justice is based on the work of two social scientists, John W. Thibaut and Laurence Walker, who combined their interest in the psychology of justice with the study of fair process. Focusing their attention on legal settings, they sought to understand what makes people trust a legal system so that they will comply with laws without being coerced into doing so. Their research established that people care as much about the fairness of the process through which an outcome is produced as they do about the outcome itself.

Fair process is based on three mutually reinforcing principles: the 3 E's—Engagement, Explanation, and Expectation clarity. We have added another element in our practice—Empathy.

- Engagement means engaging stakeholders and proactively seeking their input, particularly in aspects of the project that will affect them most. Engagement provides a sense of confidence that their opinions have been considered.

- Explanation details the decisions and makes sure the stakeholders understand the key points. You cannot assume that decisions are self‐explanatory or straightforward. More importantly, explanation should also provide the background of why project decisions were made. This provides people with the context as they try to assimilate and adopt the changes from the project.

- Expectation clarity describes the “new rules of the game.” It requires clarification of the expectations and consequences brought about by the process.

- Empathy involves putting yourself in the shoes of your stakeholders to understand and feeling the pain that the change is going to bring about. This helps you better plan to make the change process fair and just and connect with them from their perspective.

The PMO must seek procedural fairness by encouraging participative decision‐making. Two‐way communication helps dispel perceptual inequity. PMs who provide input into the decision‐making process are more likely to support and implement procedures. Conversely, estrangement from the decision‐making process can induce powerful resistance to change.

Communities and Collaboration

The idea of fair process needs a rich environment and appropriate culture to be successful. Communities of practice (CoPs) provide a fertile setting for these ideas to sprout and spread. How do you create a culture where people are excited about project management and PMO from the bottom‐up and want to engage and contribute in a vibrant collaborative environment?

A community is defined by a shared interest or expertise. Practitioners collaborate to share and develop practices in their pursuit to improve project management and PMO practices. They become a community in the course of pursuing their interest, which leads them to participate in joint activities, share information, and help each other. In the process, they build relationships that further their efforts in the field. It is these relationships and the associated interactions that make the group a CoP. They share a common body of knowledge, resources, experience, and language (jargon) that enables them to learn from and contribute to the community. Thus, cultivating a collaborative culture and a sandbox that is responsive, but with the appropriate amount of rigor and discipline. The idea of communities will be further explored in Chapter 7.

Self‐Regulating

Recently, I was running late for a meeting and as I started to speedup, my foot immediately hit the break, not because I saw a policeman hiding behind the bushes but because I encountered a speed indicator display (SID). A SID is a portable device that measures and displays the motorist's speed, to provide timely information to modify behavior to drive within the speed limit. A SID is essentially the friendly side of speed enforcement, nonthreatening but effective. Similarly, the PM processes need to be self‐regulating and nonthreatening. For example, rather than setting a project review or escalation meeting, the PMO can design and implement preset triggers that provide timely feedback to self‐regulate behavior in desired ways. Just as the SID is designed to slow traffic to a preset limit, PM processes can be used to define the boundaries with preset triggers for escalation. With growing capabilities to embed sensors everywhere, the ability to measure and provide real‐time feedback and self‐regulate behavior is increasing.

Scalable

One of the common complaints from project managers is that it takes them more time to complete the project documentation than the project itself. Even though it was a simple project, they had to apply all the steps to comply with the PMO methodology. To strive for global consistency and standards, a one‐size‐fits‐all mentality sounds good but is not practical. Projects and programs by definition are unique with different characteristics requiring diverse approaches. Scalable processes and methods can be designed to address the unique aspects of projects. A simple project may need very limited process steps versus a complex project that may require more elaborate methodology steps.

Self‐Eliminating

Good processes should have a built‐in mechanism for changing or eliminating the process. We can all identify processes in our organizations that have survived way beyond their desired purpose. There are processes that are in practice and institutionalized simply because they have been done for a long time and nobody has questioned them. Good processes should have a built‐in mechanism for changing or eliminating the process. Part of the PMO governance should be a method to conduct periodic process reviews and decide when a process or practice is no longer useful or when it needs to be updated to make it useful again.

Desire Paths

Desire lines can usually be found as shortcuts where constructed pathways take a circuitous route. While shortcuts can be frustrating to landscape designers, some planners look to them as they map out and pave new official paths, letting users lead the way. Some educational institutions, including Virginia Tech and the University of California, Berkeley, waited to see which routes evolved organically as more people walked over these paths, before deciding where to pave additional pathways across their campuses. Similarly, we advise PMOs to sense and observe the existing desire paths of methods and processes, and adapt and reengineer PMO processes along end‐user, customer, and stakeholder desire lines. Rather than an outside‐in approach, this is an inside‐out approach based on natural desires paths of customers and stakeholders.

SEVEN KEYS FOR EFFECTIVE PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND PMO FOCUS AND RESULTS

What are the themes across project management and PMOs that are thriving and perceived as valuable, delighting their stakeholders and making an impact? In our work with diverse organizations, from start‐ups to established companies, government organizations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) around the world, we have observed and codified seven themes that are common. Successful PMOs use the following questions as keys to unlock the right doors that lead to success and better focus and adoption of project management and PMO:

- Who is our customer? How do we better focus on the customer and business?

- How do we define success? How do we measure what matters?

- How can we be better prepared to deal with the DANCE and disruption?

- How can we cultivate a culture of connection, community, and collaboration?

- How can we develop and enhance overall change intelligence?

- How do we learn better and adapt? How do we develop signature practices that give us a competitive edge?

- How can we simplify and build a Department of Simplicity?

Remember, if you are not using all of these keys as questions, some of the doors may not open. You are either not aware of it or not focusing on the right things. All of the seven keys are important as you apply the DNA of strategy execution. We find that if even one of these keys is missing, PMOs and strategy‐execution offices (SEOs) can lose focus and implementation efforts can stumble.

Shaping the Future with Project Management and PMO

“By 2030, 25 percent of all transportation trips will be smart and driverless.”

“By 2030, 25 percent of buildings will be 3D printed.”

You might think that these bold statements are from one of the big Silicon Valley companies we hear about. Think again. These statements are from the government of Dubai, where they are constantly trying to find the sweet spot among the extremes. In my work and interactions with the PMO at the Roads and Traffic Authority (RTA) of Dubai, it has been an interesting journey to see how they try to balance and deliver on the bold goals, whether it is to fix the traffic problems in Dubai delivering on the goal of autonomous vehicles, or creating a roadmap for adopting 3D printing within the RTA.

Table 2.4: How to Use the Seven Keys to Unlock Effective Project Management and PMO Focus and Results

| Key | Door | Leads to … | How? |

| Customer and Business Focus: Who is our customer? How do we better focus on the customer and business? How do we become a steward of value and impact? | Customer and Business focus | Alignment of strategy execution, greater customer focus, understanding of what drives business, ownership, and accountability for results and outcomes | WITGBRFDT?—Start everything with the question What Is the Good Business Reason for Doing This? Understand your business model canvas Develop a business plan for your PMO Address how you can help run, grow, and transform the business Covered in Chapter 4 |

| Measurement: How do we define success? How do we measure what matters? | Measurement | Selecting the right metrics and continually evaluating performance and results | Define what success is? Develop a strategy execution scorecard PMO delight index Covered in Chapter 8 |

| Adaptive: How can we be better prepared to deal with the DANCE and disruption? | Adaptiveness and agility | Speed; responsiveness; agility; rigor without rigidity | Not Either/Or, but AND; Ambidextrous Utilizing paradoxical frames; finding your sweet spot between rigidity and responsiveness Covered in this chapter |

| Connection and Collaboration: How can we break the barriers and cultivate a culture of connection, collaboration, speed, and agility? | Connection, community, and collaboration | Flatter structures, engagement, and excitement, ownership, and accountability, self‐regulated governance, voluntary compliance, greater adoption | Cultivate a sandbox or studio; emulating the positive characteristics of lean start‐up cultures Covered in Chapter 7 |

| Change: How can we develop and enhance overall change intelligence? | Change‐making | Greater change‐readiness; increased change absorption and adoption capacity | Develop organizational, psychological, and emotional change intelligence Covered in Chapter 9 |

| Learning: How do we cultivate a learning environment? How do we learn better and adapt? How do we develop signature practices that give us a competitive edge? | Learning | Culture of failing fast, learning from failure, refrain from blind adoption of best practices; adoption of appropriate and useful practices | Rethinking best practices, cultivating signature practices Covered in Chapter 10 |

| Simplicity: How can we simplify and build a Department of Simplicity? | Simplicity | Elegance and simplicity; greater buy‐in, acceptance, and adaptability of processes, methods, and tools | Build a Department of Simplicity Covered in Chapter 11 |

I have seen the PMO evolve from a few project managers to an enterprise‐level PMO, placed with the director general's office recognizing its importance and impact. With numerous mega projects at the cutting edge of technology, from autonomous vehicles to getting ready for future technologies like hyper‐oop, it can be a challenge to find the balance between rigor and rigidity. As the director of the PMO shared, “It is not easy, but we have learned to focus on what needs to get accomplished, and shape the boundaries to get it accomplished, and leave the project teams to figure out the how.”

With the push toward the idea of Dubai 10X, symbolizing experimental, out‐of‐the‐box future‐oriented exponential thinking in projects, they are exemplary in how they have learned to thrive on the edge in a DANCE‐world. The way they strive for agility is by rating themselves on a future fitness indicator, which rates foresight—the depth of future envisioning opportunities, solutions, or threats and readiness with optimal processes, or rigid adherence to strategies and processes that threatens, versus reaction speed—measuring the reaction toward the opportunity or threat, as illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Future Fitness Matrix

Source: Adapted from RTA's Approach towards shaping the future 2009–2016.

Project management and the PMO is having an impact not only within government but also in the region as they have sponsored an annual Dubai International Project Management Forum since 2014, and recently they instituted an award for innovation in project management.

How can you get project management and PMO fit for the future, with the right foresight and reaction time? That is what the rest of the book is about. The next chapter decodes the DNA of strategy execution.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Traditional project management and PMO processes are about consistency and control and are designed to work well in a mechanical world, whereas the DANCE and disruption are characteristic of difference, failure, disorder, learning, and mutation.

- Standards, processes, and structures can be beneficial, but the challenge is knowing how much is right for your organization and business. Failure stems from either too much or too little governance and process. The challenge is to thrive. You need to find your sweet spot between the two extremes.

- The next generation depends on questions. In the past, we relied on answers, but in today's world as the DANCE intensifies and uncertainty increases, the value of questions goes up, and the value of answers goes down. Project/program managers and PMOs should learn to ask better questions and seek new perspectives to connect different aspects of the DNA of strategy execution.

- On the one hand, there is a need to establish rigor with a sound governance structure of methods and processes. On the other hand, there is a demand for freedom and flexibility. This is indeed a primal paradox between the need for discipline and freedom at the same time.

- Next‐generation project management and PMO is ambidextrous. It recognizes the importance of both the elements and does not focus on either/or. It acknowledges the tension between the paradoxical elements but understands that marrying the two reduces the undesirable effects of each and leads to new insights and blended solutions.

- True agility is achieved by aiming for rigor without rigidity. Balance foundational stability with dynamic agility. Strive to provide freedom with fences. Use ideas of fair process, community and collaboration, self‐regulation, scalability, self‐elimination, and desire paths to find and fine‐tune your sweet spot.