11.

THE POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS OF TOMORROW'S TECHNOLOGIES

Just as technological development has led to new forms of management in private companies, across the ages it has also influenced political development. Just think of the political effect of the Industrial Revolution. Industrialisation generated unprecedented increases in prosperity, which had an infinite number of positive effects for both states and their citizens. However, the new technologies also generated long, inscrutable value chains. These led to increased specialisation, so people no longer understood one another's lives and jobs to the same extent as before. Under these new framework conditions, three new principal philosophies emerged: Liberalism, Socialism, and Fascism – besides their many spin-offs, including Anarchism, Communism, and National Socialism. These societal models clashed and led to a great deal of violence and suffering.

The reason for mentioning this, of course, is that the technological and commercial predictions I have tackled in this book will also have political implications that we must include in our thoughts about how the future may proceed. This chapter is my take on the subject.

Three social standard patterns that often undermine civilisations

Before really going into the specific political implications, I would like to underline three permanent phenomena in civilisations, which I will believe will have a significant impact on political development in the decades to come: (1) the Karpman drama triangle, (2) over-institutionalisation, and (3) shifts in dominant moral instincts.

The Karpman drama triangle

The Karpman drama triangle relates to an irrational, and often very destructive, psychological game between people who assume three different roles:

- The Persecutor, who typically conceals his or her own weaknesses, and who exerts excessive control, criticism, anger, humiliation, violence, authority, condescension, etc.

- The Victim, who has opted for an often lifelong loser role. Everything is the fault and responsibility of other people.

- The Rescuer, who typically feels guilty, indifferent, or weak deep down inside, but who wants to compensate for this by constantly working on rescue projects on behalf of other people or the whole world and by making that mission very clear to the outside world.

An important feature of this is that people who want to play a role in this game actively seek out other people and cast them in the two missing roles. For example, someone who wants to play the Victim may look for someone else to play the Persecutor, while a Rescuer may look for Victims. It is often the self-proclaimed Rescuers that trigger the game, clearly conveying their Rescuer status via ‘virtue signalling’. Through statements, attire, or actions they make it clear to the outside world that they are the goodies: which, of course, implies that the others are not. Then they appoint Victims and Persecutors. In order to gain absolution – particularly if you have been cast as a Persecutor – you can then hand over power to these Rescuers and maybe buy indulgences in various forms.

There are many problems with this phenomenon, including the fact that it often prevents people from taking responsibility for their own lives, and it often impedes voluntary win–win transactions.

But it is extremely widespread. Consequently, through the ages, the drama triangle has constituted a philosophical foundation for many religions, each of which, in its own way, divided the world into devout Victims, unbelieving Persecutors, and proselytising Rescuers. In the Middle Ages, for example, Europe experienced countless wars and conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, both of whom regarded themselves as the devout Victims of abuse by others. So, one Karpman drama triangle reinforced the other. Additionally, in recent times, the often-violent conflicts between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland were a full-blown manifestation of the drama triangle. The same is often true of modern-day conflicts between Shia and Sunni Muslims.

Not only has the Karpman drama triangle played an important role in many religions, but in addition to theocracy (priesthood), it has also been the backbone of totalitarian movements such as Socialism, Fascism, National Socialism, and Communism and at the very core of various vendetta cultures throughout the world.

Admittedly, much of it disappeared in Europe as Christianity became gentler, the Iron Curtain fell, and national wars in Europe largely disappeared. However, already in the 1980s, it started to gain ground again in the form of the more extreme forms of eco-fascism, which wanted to rescue the world from avaricious humanity. And, more recently, it has reared its head in today's budding culture of persecution, or offence culture, in which various sections of the population cast themselves in the role of chronic Victims, while pointing their fingers at the Persecutors they want to be saved from by Rescuers.

Over-institutionalisation

The second, and frequently very destructive, repetitive pattern of civilisations is over-institutionalisation: a phenomenon that results in insight, responsibility, and consistency being increasingly removed from one another, while an ever-increasing proportion of society's activity is no longer made up of voluntary win–win transactions but is imposed. However, it is important first of all to note that over-institutionalisation is a spontaneous phenomenon that is extremely difficult to combat in conformist organisations, since their natural tendency is to create ever more of it. Secondly, it is so strong that it has not only ruined countless civilisations throughout the ages, but is also a recurring phenomenon in private companies. Thus, modern companies with conformist organisations spontaneously become increasingly bureaucratic and rigid until they often perish for that very reason.

But it is more serious when it destroys civilisations than when it causes individual companies to fail. And it certainly does destroy civilisations. In fact, for example, the anthropologist and historian Joseph Tainter, the historian and evolutionary theorist Clay Shirky, and, particularly, the historian Carroll Quigley (all three American) have indicated that over-institutionalisation has been the very factor that destroyed numerous civilisations.

Over-institutionalisation has often taken the form of religious tyranny. However, I believe that today's path towards over-institutionalisation in secular societies usually consists of the following five phases:

- Phase 1: The Minimal State. The state is in charge of people's security and handles practical tasks only in cases where these clearly are best addressed collectively.

- Phase 2: The Social Security State. The state to a greater extent helps the sick, the young, the old, and the unemployed.

- Phase 3: The Welfare State. The state also helps people of low income, regardless of whether they are jointly responsible for their own situation.

- Phase 4: The Equalisation State. The state's added objective is to level out income and prosperity through the transfer of money.

- Phase 5: The Total State. The state has a dominant role in media, education, production, freedom of expression, and people's private economy.

Whether the fifth phase – the Total State – ends up being actual totalitarianism is a matter of definition. However, the important thing to realise is that the future we are attempting to look into will, in my opinion, encounter major problems as a result of over-institutionalisation.

The collapse of norms and moral decadence

The third important phenomenon, which will also affect the future, as I see it, is a drift in people's prioritisation of moral instincts. In his ground-breaking book The Righteous Mind (2012), the social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt described six moral instincts, all of which have been important throughout millennia for the survival of cave people:

- Protection against violation (traditionally to ensure the survival of offspring).

- Fairness (to escape parasites and facilitate collaboration, including trade).

- Loyalty (to be able to support each other in adversity).

- Faith in authority (to get collaboration and lines of command to work).

- Cleanliness (to avoid infections).

- Freedom (to remove constraining leaders).

Personally, I would also say that diligence, willpower, and willingness to take risks are important moral instincts for the majority of my friends and family, even though they are not on Haidt's list. In any case, one of Haidt's well-founded theses is that we are all born with an individual symphony of instincts that significantly affect our choices in life, including our political attitudes. But Haidt also demonstrates how, in modern society, these modern social instincts are exposed to new situations, with which our distant ancestors were not familiar. One example that springs to mind is how we project our instincts of loyalty and belief in authority onto our affiliation with sports teams. And the fact that, in today's extremely clean world, our innate instinct for cleanliness often turns into food hysteria, where we suddenly think we are being poisoned by things that are really quite healthy and harmless. Or, in the Karpman version, we are Victims of poisoning by Persecutors in the evil food industry, but we can be healed by good Rescuers. So ‘detox’ has become the new buzzword.

However, moral instincts not only guide individuals in directions that are not always appropriate; they can also contribute to destructive, collective mass movements. For example, I believe that the first five of Haidt's above-mentioned six moral instincts may well be – and often have been – abused as driving forces in the Karpman drama triangle: as when non-believers are described as ‘unclean’ or when people with their instinctive faith in authority cast themselves at the feet of self-appointed Rescuers, who are actually dreamers and charlatans.

However, there may also be a shift in a society's relative prioritisation of the various instincts if it has long been spared from obvious threats. For example, statistics show a correlation between the roll-out of welfare societies and so-called norm degeneration. In tandem with increasingly better welfare services, funded by an increasingly higher and more progressive tax burden, we often witness an erosion of the work ethic. When incentives to work are reduced, some people will work less or attempt to avoid work altogether. Of course, this can be thought of as a free choice, but it becomes problematic when the same people make use of society's common, and very expensive, services. In addition, a moral decline can set in, in which increasingly more people attempt to help themselves to public funds, simply because they see other people doing it. It is somewhat similar to problems in corrupt societies, in which everyone is corrupt because everyone else is.

Any competent historian knows that this phenomenon is nothing new. There is an excellent example in the TV serial about the second president of the United States John Adams, in which Adams and Benjamin Franklin visit the all-out decadent court of Louis XV, where the men wear ultra-feminine clothes and thick layers of mascara, and live lavishly off the people's money. Meanwhile, John Adams is a down-to-earth, practical man of humble background who wants a minimal state in his own homeland. Adams is overwhelmed by the decadence and comes across like a dog in a game of skittles.

In fact, the phenomenon of increasing decadence is aptly described by the Arabian historian Ibn Khaldun in his book Muqaddimah (1377), in which he divided dynasties into four stages:

- Stage 1: Entrepreneurial leadership that builds values through diligence and thrift.

- Stage 2: A fairly efficient generation who has seen the first generation at work and understands staple societal values.

- Stage 3: A less efficient third generation operating on the basis of the now-established, efficient traditions, but without fully understanding or appreciating their deeper reasons. As a result, they are less efficient.

- Stage 4: A fourth generation that is completely lacking in the necessary virtues and understanding of – or interest in – how value is created, so they simply squander everything.

For generations now, the West has largely been spared from war on its own territory, plague, cholera, or famine. That is exactly why, in my opinion, there have been violent shifts in the prevailing moral instincts. As a result, large sections of the population have severely reduced knowledge of – and interest in how values are created and protected. So, as I see it, we are experiencing a moral decadence that does not sufficiently equip nations to tackle threats, or even to maintain the momentum of previous generations to create an increase in prosperity. In fact, I believe that, while this phenomenon is very strong, its rise is blurred by the benefits we gain from the development of exponential technologies. But the underlying threat is the fact that we may perhaps be a little too similar to the generation in Stage 4 of Ibn Khaldun's model, recklessly squandering the trusted talents.

- Due to negative self-organisation, society has spontaneous tendencies to disintegrate cf. the Karpman drama triangle, over-institutionalisation, and decadence. All three of these tendencies are spontaneous and very difficult to counteract.

It should be noted that such disintegration does not only involve money and power. When travelling around the world, I have often been amazed to see older buildings and art bearing witness to former cultures that – apart from lower technological stage – were far more sophisticated than the ones now inhibiting the same areas. And whenever I see this, it is clear that the only thing that has progressed in the area – technology – was not developed by themselves but imported from other more advanced civilisations. I suspect that the single most common reason for such cultural decline is excessive separation between insight, responsibility, and consequence, which can happen as a consequence of excessive enacting of the Karpman drama triangle as well as of over-institutionalisation and decadence.

The future welfare society – pyramid states or agile app stores?

As far as I am concerned, the aforementioned phenomena constitute general threats to our civilisations. But there are also more specific problems in modern mixed economies, where the public sector is predominantly, in Frederic Laloux's terms, conformist: method-driven and hierarchical. I believe that these organisations carry the seeds of their own destruction.

The first is the so-called Baumol effect, or ‘Baumol's cost disease’, named after the American economist William Baumol. One can easily raise wages in one sector if productivity per employee increases accordingly. Great. But then take a string quartet, which is one of Baumol's favourite examples. String quartets have not experienced any increase in productivity for hundreds of years. Nevertheless, like other people, musicians expect pay rises. That means that consumers see their services as increasingly more expensive when compared to all sorts of other things. That is why professional classical music also requires large amounts of public subsidy for its survival.

Now, string quartets are not a major factor in global economy. But the big problem is that public sectors throughout the world suffer from the same problem. Unlike private companies, they do not work under competitive pressure so have limited incentives for innovation and productivity improvements. Nor do they reward them. On the contrary, because if the public sector rationalises, some of their staff will simply get fired. In fact, as a result, over time they have nigh-on zero productivity gains, so they feel increasingly more expensive and engulf increasingly larger amounts of the GDP – even though the quality of these services does not improve. And if, as an alternative, we freeze the public sector's budgets’ GDP share, due to the Baumol effect, their quality will be ever poorer.

One of the main reasons for the lack of productivity growth in public services is the use of monopolistic method management, which is a feature of Laloux's conformist organisations. This means that those who decide what to deliver, even at retail level, through laws and directives, determine how the tasks should be solved – in other words, the exact opposite of Auftragstaktik.

Method management can be justified in certain contexts – both in the public and private sectors. McDonald's, for example, is very method managed, because uniformity here is a big priority. However, there are also a number of disadvantages associated with it, because when you take away responsibility from people, they easily become irresponsible, and when you deprive them of power, they often feel powerless. In addition, method management creates an atmosphere of distrust, because it shows that those who make decisions do not trust those who work. Method management also stifles creativity, because it puts a stopper on experiments.

Similarly, over time, method management leads to such complex regulatory jungles that increasingly fewer people can find their way through them. On top of that, administration costs constantly grow – partly because, as Laloux pointed out, conformist organisations generate very large staff functions. And finally, it should be noted that method management freezes organisations or societies in states that totally hamper them from keeping step with an ever-evolving reality. In other words, excessive method management amounts to over-institutionalisation and, the faster technological development proceeds, the more hopeless the states’ lead-footed method-management model becomes.

Another reason for the Baumol problem is that, in general, we manage other people's money less responsibly than we manage our own. One example is the so-called budget-maximising model in public sectors, which was scientifically described for the first time in 1971 by the researcher and university professor William Niskanen. Public servants typically attempt to increase their own organisations’ budgets in order to gain more subordinates and more power. This is a lot different from private companies, in which managers typically try to maximise their profits by reducing costs and thus headcount and generally improving performance.

We also have Mancur Olson's Non-Work Law. Large bureaucracies typically produce a myriad of working committees and sub-committees, each of which works increasingly more slowly, creating unproductive work for each other. The sum of all this is rather disheartening:

- Public institutions tend to gobble up increasingly larger amounts of a society's economy, while their efficiency lags increasingly further behind.

Due to the combination of Baumol's cost disease and norm degeneration, modern welfare states have often had a steadily increasing tax burden, which I regard as a major problem in itself. In fact, the aforementioned Ibn Khaldun had already described at as follows: ‘It should be known that at the beginning of a dynasty, we get substantial tax revenue from low tax rates. When it ends, we get poor tax revenue from high tax rates.’ I can elaborate on this with some obvious examples of the harmful effects of too high a tax burden:

- It is mainly detrimental to creative enterprises, since many artists, athletes, entrepreneurs, and others, who work with great uncertainty and variable earnings, have very uneven incomes. They often alternate between being top taxpayers and being in financial distress, when they then apply for social security. The distress is very much a result of the fact that, because of their sporadically massive tax bills, they were not able to save in good times for the subsequent bad times.

- Excessive taxation destroys division of labour and jobs. If Mr Smith, a tradesman, offers to paint a wall for a homeowner, Mr Brown, and if both pay a marginal tax rate of 50% plus 25% VAT, Mr Smith has to be about five (five!) times better at painting than Mr Brown before it makes sense for Mr Brown to pay for Mr Smith's services. And, if the marginal tax rate is increased to 70%, the requirement for greater efficiency increases to 14 times. This phenomenon pressurises many people to leave the labour market, and they become welfare recipients instead.

- It leads to more undeclared work, since the temptation for this increases with the tax burden.

- It causes more social fraud. People who live off undeclared work seek social benefits to justify the fact they do not have an official job.

- It increases the brain drain. The most talented, risk-taking, hard-working professionals flee from countries with excessive taxation.

- It results in less physical mobility. Particularly high car taxes reduce people's willingness to work, where there is no easy access to public transport.

- It leads to unproductive saving. Instead of investing their savings in productive companies (shares), where the money is taxed, people conceal their profits in unproductive things such as gold, jewellery, or home improvements, which the tax authorities have a harder time spotting. This is especially true if the money comes from undeclared work or crime.

- It hampers innovation. It makes less sense to take risks as an entrepreneur if any winners are taxed to the hilt.

- It counteracts job mobility. Heavy taxes prevent people from saving. Therefore, they dare not change jobs or industry, let alone start their own business.

- It costs a fortune in administration. The more punishing taxation becomes, the more resources are deployed on administration, collection, optimisation, punishment for evasion, etc.

While public administration continues to be based on Laloux's conformist management model, the overall consequence of the above-described challenges is a tendency for tensions to get even worse over time.

There is also a threat that a so-called ‘welfare coalition’, most of whose income is from the state, and who can vote to get the money of a minority, which could also ultimately lead to collapse.

Forces that lead to chronically low growth or stagnation in welfare states

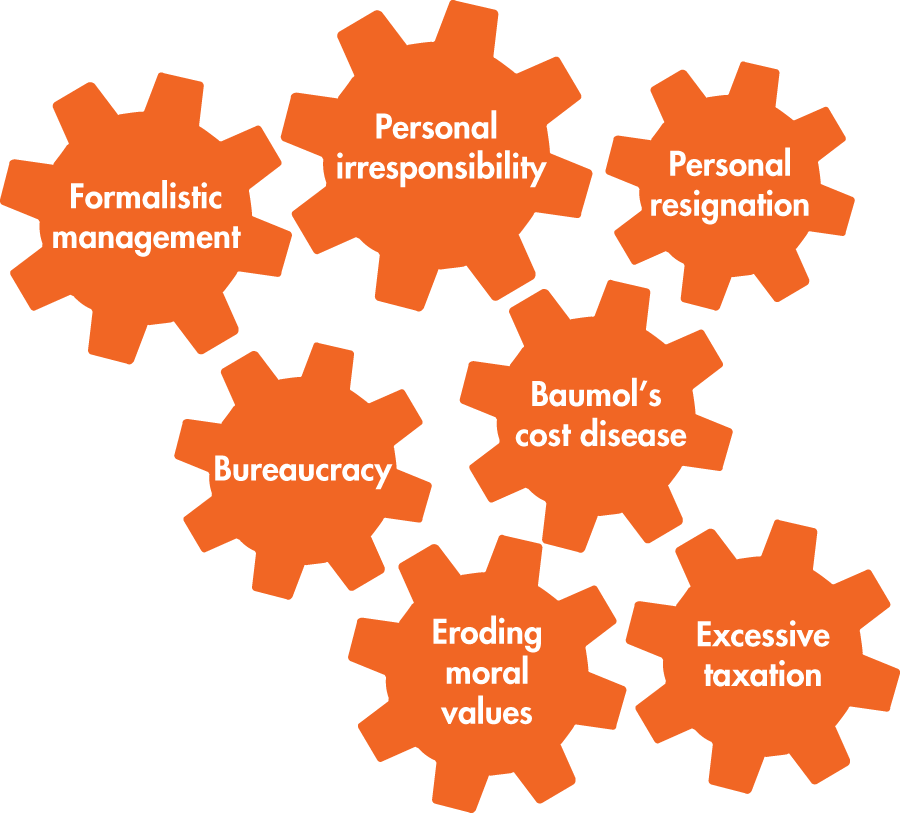

The sum of the aforementioned societal problems is, as mentioned, that modern mixed economies contain the seeds of their own potential destruction. The Karpman drama triangle, persecution culture, over-institutionalisation, moral decadence following crisis-free periods, Baumol's cost disease, negative norm degeneration, and sky-high taxation can lead to persistently relative, and finally maybe absolute, deterioration. That is what happened, for example, over many decades in Argentina and is often somewhat similar in the second, third, or fourth generation of successful families.

The battle for top–down management and decentralisation

In my view, there is a huge underlying tension in society between those who are mainly advocates of public power concentration and a hierarchical society, and supporters of more decentralised, grass-roots communities.

When it comes to the public sector, hierarchical models took over a long time ago. In my native country Denmark, for example, until the 1970s just over a few thousand parishes were important power entities, but then most of that power passed to the municipalities, which were then merged, just as the counties had been merged to form regions, which were then again merged. And while all that was happening, more and more power was channelled to parliament, which then forwarded increasing parts of it to the European Union, the United Nations, and other international organisations. In other words, the power was continually moved further away from individuals and local communities and concentrated at the top of increasingly larger entities. Arguments on behalf of this trend have often relied on the benefits of ‘common solutions’ and ‘harmonisation’.

As we have seen primarily in China, centralisation can be promoted with technologies such as IoT and big data to monitor people via sensors and behavioural analyses, and AI to locate threats to the system. It is thus possible to take centralisation far.

So, the public sector has predominantly centralised, which is a natural tendency for Laloux's conformist organisations, whereas the private sector – as we saw, for example, in Chapter 11, predominantly through apps, crowdsourcing, blockchain, MOOCs, the sharing economy, the rating economy, 3-D printing, and DAOs – has decentralised. This is an often profitable opportunity which we see in Laloux's achievement organisations, and which is key to his pluralist organisations and essential for the evolutionary ones that are now emerging.

Technologies that can promote decentralisation

In this context, it is important to understand that a decentralised market economy is at the heart of creativity. For example, it has a built-in sorting mechanism, in which ideas are constantly filtered through the ability to attract the right team of entrepreneurs, to convince financiers like me, and appeal to commercial customers like us all. Overall, a market economy is thus evolutionary, even if its companies are not individually so.

This is supported by the fact that today information flows much more freely. Traditional media such as books, radio, and TV were all based on top–down methods to spread information from the few to the many. But the Internet enables information to flow up, down, and sideways – you name it – completely freely, based on grassroots models and through millions of interlocked seek–sense–share loops. Thus, the information flow has become evolutionary, undermining the assumption in conformist organisations that the elite knows much more than the rest of the people.

Currently, ground zero for the debate on centralisation versus decentralisation is perhaps the European Union. Here, two very different views are confronted. Germany and especially France – albeit with considerable internal resistance – are pioneers of the view that the European Union must be centrally controlled like a kind of Roman Empire with common solutions and harmonisation. Conversely, a number of peripheral countries are more in favour of becoming an EFTA for free, autonomous nation states: free trade and political diversity. This tension also involves a clash between a conformist and an evolutionary societal model.

If this conflict is not to end up as a very bad marriage, it may be necessary to divide into two or more EU membership provisions, ranging from large-scale to small-scale centralisation. If this does not happen, I predict that the bad marriage may get really ugly, as such marriages often do.

Openness or closedness?

We have seen that, unless there is immigration, people in wealthy nations have too few children to stabilise their populations. At the same time, there are prospects of major population growth in the poor parts of the Middle East and large parts of Africa. This will of course continue to support mass migrations, which again will cause many countries to restrict immigration. One argument for this is that welfare states would soon go bankrupt if they had open borders and offered welfare to every Tom, Dick, or Harry that came in. Conversely, inhibiting migration can be costly when it comes to people who could play important roles in the labour market. Indeed, some of the most creative and economically well-functioning regions in the world have highly international populations.

In this context, I think that countries – for example, EU countries – will gradually come up with models in which borders are conditionally open, the conditions being that immigrants can support themselves and abide by the rules. This is, for instance, the basic model in Switzerland, which, besides having a relatively evolutionary social model, is one of the most international countries in the world. But it is also pretty good at preventing immigrants from draining public funds or making a living from crime. I can imagine a future in which that kind of ‘smart openness’ will gain ground.

The information problem in public management

Public sector management also has a growing information problem, since the difference between the population's vast collective knowledge and the state elite's comparatively limited insight is increasing. It is fair to say that a clan leader in the Stone Age probably shared a significant part of his clan's overall knowledge with others, but this is, of course, not the case in highly advanced modern societies with extreme division of labour and much larger entities.

Two of the first people to highlight this central theme – and at a time when it was a lot smaller – were the Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, both of whom described how information in a society is spread everywhere. Every day, every single person – the schoolteacher, the craftsman, the businessman, the researcher, and everybody else – collects and processes complex information from his or her own world. Assuming that an elite is supposed to control the behaviour of all these people on the basis of the hierarchical model, it is unlikely that it can possess more than a fraction of a percent of an entire society's overall knowledge and insight. So, supposing optimistically that it has 0.1% of the total knowledge, on the basis of that 0.1% of society's knowledge, should it have the right to tell the people, who have the remaining 99.9%, what to do about most things in life?

Hardly. And that is why decentralised systems tend to perform best. Decentralised systems also gain in the long term, because they have far more experiments and much more competition; and since the trinity of knowledge, responsibility, and consequence is united in decentralised systems, they motivate people to a much greater extent. Incidentally, Nassim Taleb presented this theme very nicely in his book, Skin in the Game (2018). The book's main point is that, if people will not live personally with the consequences of decisions, then they should not be making them. Consequently, I will take the liberty of naming this book's penultimate law after him:

- Taleb's Law: The systems in which insight, responsibility, and consequence are closest to one another usually do best in the long run.

When client–server computing made it big, it outperformed many companies, who still advocated master–slave computing. And that has also been the case with every subsequent computer paradigm. The strong philosophies of decentralised intelligence and information, which form the basis of recent computing paradigms, such as client–server computing and later personal computing, network computing, edge computing, and cloud computing, also annihilated companies that did not keep up with the progress, and they continue to do so. But, in my view, the really striking phenomenon is that states are allowed to base their behaviour on conformist organisations, who not only resemble the master–slave computing model of mainframe computers, but who also increasingly do so. So, my prognosis is partly that, going forward, power and prosperity will be concentrated in those countries that best understand how to convert from a master–slave societal model to personal network–edge–cloud-like systems divided into countless discreet, logical entities, each with a fusion of its own insight, responsibility, and consequence: cf. Taleb's Law. In other words, the future will be dominated by states that depart from conformist organisation in favour of achievement, pluralist, and – last, but not least – evolutionary organisation forms.

Laloux compares impulsive organisations to packs of wolves, conformist organisations to military ones (without Auftragstaktik, I would add), achievement organisations to machines, pluralist organisations to families, and evolutionary organisations to living organisms.

Yes, living organisms. In this respect, it is interesting that Taleb's Law also works in nature. Just think about how nature is organised: in a myriad of small, rational, and autonomous cells, each with its own chemical algorithms for making useful decisions. A human body, for instance, consists of billions of cells that together create organs etc. And each cell of every single organ is programmed to filter what is going in and out, and to respond logically to external impulses. Biology, which could not be more evolutionary, is thus very much based on edge computing. It is this organic decentralisation principle that we elegantly copy in a predominantly market economy society or in a technology such as IoT and a business model such as the sharing economy – and in evolutionary forms of organisation. In other words, from the outset, nature has dangled this in front of our noses, and now we see its principles deftly applied to electronic ecosystems and increasingly to private business models too.

That is the next thing for states to learn. Thus, in the public sector management of the future, we must seek more evolutionary and hacker-friendly societies, which consist of smaller autonomous entities, each of which can easily be substituted with others via an open platform, and in which money to a greater extent follows the citizens, who can then choose their providers in publicly sponsored ‘app stores’. This could be done, for example, by offering people certain amounts of crypto money, which could each be used specifically for special purposes such as education. Originally, economists called this phenomenon a ‘coupon economy’. But, if it were based on blockchain, ‘token economy’ would be a more appropriate expression.

The Roman Empire

So, what is my actual prediction in this case? Unfortunately, it is that states – especially the larger ones – will be bad at converting from conformist to more agile models. Those who do manage to will become magnets for migrations of dynamic people and for growth-oriented, profitable companies. The formation of the evolutionary state is perhaps one of the most underexploited opportunities in our society.

In reality, maybe the fall of the Roman Empire and what came after might be a good reference vis-à-vis what we are starting to experience. The Roman Empire in Western Europe existed from 27 BCE to 476 CE. Its fall came pretty quickly. It took just 71 years from being close to the peak of its greatness until it was brought down by Germanic tribesmen. Subsequently, the next 500 years or so saw the emergence of a belt of thousands of city states stretching from (and including) present-day Northern Italy to Switzerland, Germany, Eastern France, the Benelux, and parts of Northern Europe. As I mentioned before, these city states witnessed tremendous creativity, and this decentralised structure led to experimentation, enabling inhabitants to migrate to wherever the best opportunities were. A major analysis of this period's migrations by the US institute of analysis, NBER, concluded, for example:

As measured by the pace of city growth in western Europe from 1000 to 1800, absolutist monarchs stunted the growth of commerce and industry. A region ruled by an absolutist prince saw its total urban population shrink by one hundred thousand people per century relative to a region without absolutist government. This might be explained by higher rates of taxation under revenue-maximizing absolutist governments than under non-absolutist governments, which care more about general economic prosperity and less about State revenue. (Long and Shleifer, 1993)

That is what we are already seeing, and I believe it will intensify. So, I think that what we are going to experience politically in the West might be reminiscent partly of the final stages of the Western Roman Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire was conquered by Muslims in the fifteenth century), and partly of the creativity and voting with feet which later occurred among the numerous smaller city states.

Government as a platform: small government – big services

One way to mitigate the risk of systemic political crises is to pursue government as a platform.

In this context, think of smartphones. These provide access to millions of apps, all of which have been tested to meet certain legal, security, and quality requirements, but which were developed externally. In other words, smartphone providers crowdsource the vast majority of their services, which users then rate. This creates a huge range of different services at very competitive prices (many services are even free) and promotes incredible innovation.

One prerequisite for this has been the fact that smartphone providers offer Application Programming Interfaces (APIs): in other words, well-defined software interfaces that facilitate the easy integration of foreign software with theirs. Similarly, in a government-as-a-platform model, you could imagine that public data and services would be very open, so that individuals could work with them and make extensions, plugins, etc.

But that is not all. Imagine a state that says: ‘We want to offer all citizens tax-funded access to a range of services such as education and health insurance, and we will ensure that they comply with certain requirements. But each citizen can choose his or her own providers.’

This is the platform concept in a nutshell, abandoning method-managed monopolies and instead promoting competition and choice, and thereby generating innovation and productivity gains. In such a system, insight, responsibility, and consequence will also be more closely linked in a number of local units, which corresponds somewhat to converting from master–slave, mainframe computing to networked and edge computing. The consequence is that service providers spend less time fulfilling the requirements of public method-management systems, instead focusing more on their customers.

But how would customers choose? Through rating systems, which would emerge spontaneously. However, in addition, the state may require any service provider on the public platform to disclose certain information, such as average grades in a school or current waiting times at a clinic. Smartphone providers and other modern companies almost always have online dashboards, which display in real time their most important target figures such as sales, complaints, revenue, data flows, etc. In other words, they know precisely – here and now – where the proverbial shoe pinches. But if public services are offered by private or autonomous companies, customers must also know where the shoe pinches – here and now.

Another development in public services may be that an increasing number of approvals etc. can be booked online via small smartphone apps and websites, which provide immediate answers to most of them, similar to how people get order confirmations and delivery estimates in seconds when ordering online from private providers like Amazon.

And when the state itself provides services, it can offer real-time tracking of case handling. It is rather like having packages shipped by private providers, where you can usually see online exactly where in the system your package is at any moment, or where, in the case of Uber, the car you ordered is in real time and when you can expect it to arrive.

Moreover, such real-time feedback is not only useful for the customers/citizens, but also for the providers. Politicians and public sector administrators will also become much more efficient if they see how well the systems are working via online, real-time dashboards. And when something does not work, it will be clear to everyone who is responsible.

The growing attraction of basic income

Another aspect of technological development may be an increasing argument for basic income. As mentioned earlier, I am personally not so concerned about mass unemployment as a result of new technologies, but it seems likely that welfare states in the West, in their current forms, will run into some major problems. First, experience shows that welfare states create incredibly expensive management and control regimes. Welfare, machinery-related administration costs for both a state and its citizens combined can easily reach 20–25% of the revenue collected in taxes. Secondly, welfare states can maintain clients in inactivity, because even the slightest sign of willingness/capacity to work can lead to loss of benefits: a relationship that ends up attracting some people to assume chronic client roles, akin to the perpetual Victim in the Karpman drama triangle. This is why basic income may be chosen to replace lots of the traditional elaborate welfare system.

In fact, there have been experiments with this in several places in the world with limited success. See, for example, Rutger Bregman's book Utopia for Realists (2017) for a description of such attempts.

However, the success criterion for introducing a basic income must be, partly, that such a system only ensures a quite limited lifestyle and, partly, that any work can actually be worthwhile, so the basic income in no way becomes unnecessarily passivating.

It is also interesting that basic income has advocates from all parts of the political spectrum. For this reason, too, it seems likely to me that different countries will experiment with it again and perhaps eventually find a model that works. If I have a single major fear vis-à-vis such a project, it is that it will make it easier for parts of the population to live like totally pacified screen zombies, sinking into the digital world and becoming totally cut off from real life.

Value-based public management – good or bad?

In Chapter 11 I described how, more than ever before, in a turbulent future, private companies will need to have, and communicate, clear values. Value-based management in a company means you only hire people who agree, and that is what you then try to do.

But does the same apply to future states? In this context, the answer is somewhat less black and white. Every nation has a set of basic values expressed in its constitution, and I believe that most people in most nations support their constitutions. However, major migrations mean that increasing numbers of population groups are migrating to countries whose constitutional values are not theirs, and to which they are sometimes directly opposed.

The basic problem is that you can only have value-based public management if there is overwhelmingly common support for these values in the country's population – and that requires a certain degree of internal homogeneity. This particular issue, by the way, is described excellently in the last chapter of the classic book State, Anarchy, and Utopia (1974) by the philosopher Robert Nozick. If states are, or become, too large or multicultural to meet this criterion, the tasks of that state should be reduced to the purely practical. If this does not happen – if the state pursues core values that large parts of its population disagree with – you will lose trust and coherence. And that is happening in quite a few places.

If I have to draw a general conclusion about how technical development both challenges and offers new opportunities to public management and administration, the overall task must be to gradually reduce the use of conformist organisational models with their vast legislative jungles and frequently unrealistic leaders, and to arrive instead at something that combines achievement, pluralist, and evolutionary forms of organisation. In this context the keywords include ‘government as a platform’ and maybe ‘basic income’.