This chapter will consider the subject of rapport which is central to NLP practice as well as being the guiding principle for change leadership efforts. Rapport is, arguably, the magical ingredient that is at the base of all successful relationships and, thus, is seen by NLP trainers and practitioners as a vitally important skill. The early developers and pioneers behind the birth of the NLP movement spent considerable time modelling excellent examples of rapport strategies. They modelled the rapport-building skills of world class therapists who achieved consistent success at guiding clients through complex personal and family change.

Much of the literature concerning change management leadership describes fault lines which undermine a change programme as being connected to resistance on the part of stakeholder groups. This negative identity creates a problematic tension between those who support the change programme and those who do not. NLP offers a paradigm that disrupts this kind of them versus us thinking. NLP advances the view that ‘resistance is a sign of poor rapport’. Thus, NLP practitioners accept responsibility for their social results. If change participants are resisting our leadership efforts and are framing our communications in ways that are disabling the realization of our intentions, then for NLP practitioners this is a product of our own inability to build rapport. We must reflect on the social strategies we are employing and use the feedback constructively to adopt a different approach to build rapport. This type of thinking is known in organizational studies as reflective practice and NLP practitioners are, by definition, reflective practitioners. In this chapter I shall survey NLP techniques and ideas which can enable rapport-building processes to emerge as significant change leadership skill sets.

Defining rapport

Rapport is defined as low resistance between two or more individuals which enables alignment of values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours. Rapport is a magical dynamic which enables influencing processes and winning friends. People do tend to like people who are like themselves. This is how Dilts and DeLozier (2000, p. 1051) frame rapport.

One of the most important relational skills in NLP is the ability to establish rapport with others. Rapport involves building trust, harmony, and cooperation in a relationship. ‘Harmonious mutual understanding,’ ‘agreement,’ being ‘in tune’ and ‘in accord,’ are some of the words used to describe the process and or the state of being in rapport with another.

These two NLP pioneers also cite Webster’s Dictionary which defines rapport as a state of ‘sympathy which permits influence or communication’. They make the point that the quality of information you can exchange with others is dependent on the degree of rapport you have with them. In their book Introducing NLP O’Connor and Seymour (1990, p. 234) define rapport as: “The process of establishing and maintaining a relationship of mutual trust and understanding between two or more people.”

Dilts and DeLozier (2000, p. 1051) employ the metaphor of a dance to advance their definition of rapport. They position rapport as an improvised process that is nonlinear, that is, in fact, a creative matching of the rhythm of mind, body and soul. When one is trying to build rapport, one is subtly dancing with the world view of the other, a process that is called ‘pacing’ in NLP. Pacing enables rapport. The aim is not to inculcate the world view of the other, rather when building rapport, one is trying to respect the world view of the other and to understand it so that the channels may open between people.

Rapport can also be defined as ‘the quality of a relationship that results in mutual trust and responsiveness’. Rapport refers to a form of relationship between people that enables mutually beneficial sense making. Rapport is the cohesive element in social relations that enables social bonding between people. When one is in a state of rapport with another person, or with a group, it is an experience that can be considered as being in tune with others. Rather like the frequency of a radio station, when building rapport, we are literally tuning in to the other’s wave length. Rapport is an essential part of society’s structural and cultural dynamics. It is difficult to conceive of a cohesive and stable society or culture in the absence of rapport.

Rapport as a performance indicator

The strength of rapport between two people can define the quality of the relationship they have with each other. In many ways the absence or strength of rapport established between key stakeholders during change projects functions as a key performance indicator. A lack of rapport, or very weak rapport, should be a cause for considerable concern amongst the change leadership group. Rapport involves an incremental social process that opens channels for generative dialogue.

Building rapport with key stakeholders is a critical part of the leadership process. There is little doubt that an inability to both understand what rapport is and to consciously build rapport with key stakeholders is a fault line that runs through change projects. In a management career spanning 25 years I cannot think of a time when I received training regarding rapport building. The reason for this, I think, is that rapport is simply not considered as a key leadership skill. It is a social skill that is often expected at a level of unconscious awareness and yet it is, arguably, one of the most important skill sets a change leader in an organization can possess. To be in a state of rapport one requires empathy and curiosity in relation to others and their perspectives.

Building rapport is a social skill that we all have the capacity to develop. Rapport can be defined as ‘the ability to elicit positive responses from the other’. This ability is an essential competence required to establish you in a leadership role. Rapport builds trust and strengthens relationships which, during periods of intense change, are critical human resources.

Dale Carnegie (1936) asserted that the ability to build rapport and manage productive relationships was key to business success. Rapport is the aim of NLP. It is the meta-guiding principle of NLP. Beyond the practice of NLP, the ability of the individual to function competently and with success in the broader social world is hugely influenced by their ability to establish rapport with people.

Rapport is a magical dynamic which, as Carnegie (1936) said, enables influencing processes and winning friends. An essential performance indicator for rapport is when we can see and hear two or more people being comfortable in engaging in dialogue. Rapport involves matching the body language, voice tone and representational systems of those we are trying to engage with. Leaders will struggle to lead unless they can build rapport with their followers. This means that they must develop their communication skills, including matching the way in which different people perceive the world.

Matching strategies also include matching body language, voice tone, breathing rates and thinking strategies. It can also involve matching the clothes we wear and the cultural norms of an organization. Leading successful change is only made possible because, by adopting a leadership role, we can convince others that it is in their interest to engage in reflective and generative dialogue to review culture at work with a view to changing or transforming aspects of its dynamics. This can only start from a position of rapport.

It’s in our DNA

As we develop as human beings we unconsciously develop our rapport-building skills. What happens is that through time we bond culturally with people who are like ourselves. This is one of the universal principles of human nature; people like people who are like themselves. If this is the case, then the ability to establish rapport with another person is critical to getting on with that person and eliciting their support for our activities. As previously stated in change management terms, be it at the level of the individual, the group or inter-group, the ability of the change manager to establish rapport is a critical determining success factor.

Rapport as a bridge towards dialogue

Rapport, for me, is the bridge that takes us to a state of ‘generative dialogue’, which is the essential ingredient to enable successful collaboration and the leverage of the collective intelligence of a team. When one is in a state of active rapport with others one can access a state of generative dialogue; this is defined by Isaacs (1999) as ‘the art of thinking together’. Rapport induces cohesiveness and a readiness for joint decision making and action, it ensures that working relations are fluid and coherent. People who are in rapport tend to enjoy the experience of socializing together and, thus, they have an emotional investment in protecting and maintaining their rapport. It should be clear that the ability to build rapport with others and then maintain it over time is a highly valuable skill set. The learning of this skill set followed by its successful practical application is a significant aim of NLP as a body of learning and practice.

Collaborative change is only possible if there are leaders who are capable of building rapport with followers. It follows, logically, that the practice of generative dialogue on both vertical and horizontal levels throughout the change community is a critical part of the successful change mix. Dialogue aims to release the ‘authentic voice’ that we all have inside of us. Dialogue aims to enable change participants to adopt open, differentiated, and integrated perspectives. It is through dialogue that meanings are constructed and flow; so, it is only through dialogue that meanings can be changed and, thus, change interactions must be enabled through dialogical processes.

Rapport-building model

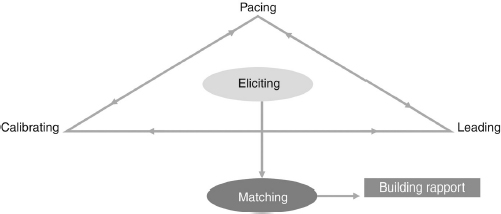

NLP developers have identified the critical processes involved in establishing rapport with people. These processes do not have a hierarchy of importance in relation to one another. They must be blended together by the practitioner to be effective. Although they do have a natural linear order there is a series of logical stages for each process to be actualized by the practitioner to establish rapport. Though, once rapport is established one would enact the different processes at different times depending on the nature of the symbolic interactions taking place between people. Figure 14.1 provides an illustration of the main process categories involved in rapport building.

Calibration

Calibration is defined by Dilts and DeLozier (2000, p. 137) as “the process of learning how to read another person’s responses in an ongoing interaction”. To calibrate involves developing sensory acuity which involves the ability to be very sensitive to the physiological and tonal cues that signify the state of mind of the individual or group. So, calibration involves the conscious process of reading the state of the other, and sensory acuity is the practice of refining one’s calibration skills to the level of micro observation.

To attain rapport, one needs to be able to calibrate the state of the other with skill. This process involves accurately assessing the mental state that the other is in through assessing their verbal and physiological cues. By studying accessing cues, such as body posture, movements, voice tone, breathing rate, and sensory systems employed, one can obtain a reasonably accurate picture of the state of mind someone is in. This process of calibration means that one can select the appropriate behavioural, emotional or cognitive strategy to match the state of the other person. You may choose a strategy which aims to pace the experience of the other.

Unconscious calibration

When people are in a group they will form social relationships with each other that will determine the dynamics of the group. There will be leaders of varying influence who will influence the group during the interaction. Often group members will unconsciously calibrate not only you as the proactive rapport builder but also their peers and, in particular, the significant others within the group. Their unconscious mind will interpret micro signals which function as meta-messages amongst the group and which stimulate attitude formation. An important part of rapport building is the ability to track through active calibration the meta-messages being unconsciously generated within the group and, if possible, being able to disrupt these by breaking the emerging group state and eliciting a different state that is favourable to your agenda. This may involve pacing and then leading which can also involve adopting characteristics that are not necessarily part of one’s normal repertoire. In many ways the skills used in calibrating and then leading a group are akin to the skills of an actor.

Calibrated loops

Dilts and Delozier (2000, p. 140) define calibrated loops as “an unconscious pattern of communication in which behavioural cues coming from one person trigger specific responses in another person”. The critical nature of calibration loops is that they serve to reproduce unconscious behavioural patterns in others. They act as stimulus to these behaviours. Obviously, if the generative behaviour is deemed as positive, calibrated loops are to be welcomed; however, if they generate negative behavioural strategies that disrupt rapport then they must be disrupted and changed.

Matching

The saying ‘people like people who are like themselves’ can be taken as a generalization about an important aspect of human nature. Human beings use culture to produce shared meanings, values, assumptions, beliefs, attitudes, habits, and behaviours that bind a group together and which provide social stability. This phenomenon has been studied extensively by anthropologists and sociologists and is called the ‘cultural paradigm’. The existence of the cultural paradigm as the expressive engine of a cultural group is generally accepted as a universal cultural theme running through humanity. People also share meta-programmes which is an NLP term for the cultural themes or rules that guide the thought processes and sense making of individuals and groups within a particular cultural context. If you try to build a relationship with someone and if you hold a contrasting meta-programme and cultural paradigm, then it may prove difficult for you to build rapport. Therefore, one has to match aspects of identities in order to put a person or group at ease and to create a dynamic where their channels are open to your suggestions and ideas. What you are trying to do is to establish something in common symbolically between you. You are trying to break the potential for mismatching which can disrupt rapport-building processes. According to Dilts and Delozier (2000, p. 698) matching is:

An interactive skill, matching refers to the process of reflecting or feeding back the cognitive or behavioural patterns of another person; for example, sitting in a similar posture, using the same gestures, speaking in a similar voice tone are examples of behavioural matching.

Thus, matching involves adopting similar body posture, voice tone, and representational systems to the other. If you match effectively you will act as an unconscious mirror to the other who is more likely to relax with you and enter into a state of rapport. You must not be too obvious in your matching strategy or you run the risk of making the other self-conscious and uncomfortable. You can subtly match by adopting similar physiology but not, necessarily, identical. For example, if someone is an auditory sense maker and they nod their head in rhythm with their speech tempo you may gently tap your finger in correspondence. Or if someone sits with their legs crossed one over the other you may sit with your legs partially crossed. This is known as ‘cross-over mirroring’.

Pacing experience

This process involves respecting the model of the world expressed by the other and demonstrating that one values and ‘sees’ their position without being at all judgemental. One does not have to agree with a person’s map of the world, although it is important, if one wishes to build rapport, that one respects it. Dilts and Delozier (2000, p. 910) define pacing as “the process of using and feeding back key verbal and non-verbal cues from the other person in order to match his or her model of the world”. You cannot lead another unless you are prepared to pace their experience and map of the world. Pacing involves matching your experience of the world with that of the other. To pace effectively you would match the appearance, physiology and lead sensory system adopted by the other.

To achieve rapport, you must establish what it is that is important to you and to the other, and establish a common interest. You must also be sensitive to the world view of the other and respect differences in relation to your own. It is a good idea not to criticize their world view or reveal your own in terms of its differences. As you match and align your criterion with the other and respect their world view you are effectively pacing the other’s experience of their world, their own map of reality. Once you are firmly established in your pacing strategy and rapport is also established, at least on the surface, you may then start to lead the other person slightly away from their fixed world view to accommodate your alternative perspective – if there is one – or to support the achievement of your criterion.

The art of pacing is regarded as a critically important aspect of NLP applications. It is also arguably a highly underestimated leadership process and, as such, is fundamental to the rapport-building process. Dilts and Delozier (2000, p. 909) continue:

Pacing is the process of feeding back to another person, through your own behaviour, the behaviours, and strategies that you have observed in that individual. Pacing involves recognizing and acknowledging another person’s behaviour and model of the world.

Basically, what you are trying to do when pacing is to complement the sense-making processes and emotional and cognitive states and strategies employed by your audience so that they feel at ease with you and confident, at an unconscious level, in your company. This degree of acceptance enables rapport-building processes. You are trying to respect and acknowledge the experience of the other person by describing their representational content through matching and listening.

Elicitation

Elicitation involves bringing forth the emotional content and mindset attached to an experience that a person has constructed. A good example of the elicitation process would involve a group of people meeting to discuss a change project. One person is the change manager and the others are members of the general management team to whom the change leaders need to sell the idea of the change project. Each person may bring with them a unique thinking style which is imbedded in an emotional mindset. One could usefully call these thinking styles dynamic identity positions towards the idea of the change project. I say dynamic because the idea of elicitation is that one can elicit a different emotional mindset in a person and, thus, change the nature of their identity position towards the change project. For example, there may be a realist, a sceptic, a dreamer, or an optimist in the group. By calibrating thinking styles, one can pace each person’s model and match their identity in subtle ways using suggestive language patterns. For example, when dealing with the critic one could say “you know John it is well known that 70% of change programmes such as this often do fail”; then one can turn to the optimist and say “however, we are not only interested in why these fail we are also interested why the other 30% have such amazing success”.

Such language patterns do help build rapport even when faced with a challenging audience. Also, John must reflect on the way the change manager framed the prospects of success associated with a change programme. The change manager did not contradict John’s model of the world, rather she paced it and offered a reframe which suggested to John that both ideas were true; change programmes often do not work, and, in some cases, they do work. Such a reframe means that John, if he thinks about the content, will shift his emotional state and his mindset. When we mix internal representations, we cannot help but create a new mindset.

Leading

Once you are in a state of rapport, you can make efforts to lead the other from their current state to another state of mind. This process involves effective elicitation. For example, if you wish a group to shift their state from being defensive to being curious, this is an attempt at leading in NLP terms. If you simply try to do this through the medium of monologue, unless you are a gifted orator, you may find leading challenging. If you apply the techniques of calibrating, matching, eliciting, and pacing your audience, and engage them in conversation you will have an improved chance at leading their shaping of their particular world view.

Leading is a very delicate process. It involves presenting your own ‘perceptual position’ to the others in a way that enables them to build a bridge between their own personal map of reality and the new map that you are introducing. If you do this in a way that is acceptable to the others, then you will be leading the client and will have successfully bridged between alternate perceptual positions. This is when you are in a state of generative dialogue and are effectively thinking together. Leading basically involves subtly changing from matching to offering different thought processes and behaviours and inviting the other to follow you. A test of whether you are leading or not is if you deliberately shift your posture or voice tone or speed and the other follows you, unconsciously matching, then you can be confident that not only are they in rapport with you, they are also following your mental strategies.

If the others follow your line of thinking and engage in dialogue with you, then you have successfully bridged and built rapport. This is a critical change leadership skill. It does not guarantee that others will simply fall in line and agree with the case for change and behave in a supportive manner, however, it does mean that they are open to dialogue and change. What you can be sure of as a change leader is that if you don’t build rapport, you don’t build perceptual bridges, you will not establish dialogue, and, in the absence of generative dialogue, you will not establish collaborative working and leverage the collective intelligence of the group.

Internal rapport

A central component of managing rapport is managing one’s own internal rapport with one’s self. This idea may at first seem odd; however, I think that it is key to understanding the secret behind relationship management. If one cannot get on with oneself. how one can realistically expect to build sustainable rapport with others? The aim of self-rapport management is to achieve a state of congruence between the unconscious mind and the conscious mind. For example, your conscious mind may rationalize that investing in a new house is a sensible thing to do, whilst your unconscious mind feels uncomfortable with this decision. This happens because the conscious mind can only accommodate 7 plus 2 or minus 2 pieces of information at any one time. In contrast, the unconscious mind holds all the life experience and associated knowledge we have and can make sense of this vast reservoir of knowledge at incredible speed. If our rational conscious sense-making is not congruent with our deeper unconscious sense-making we will feel uneasy, and this feeling of being uneasy manifests in our emotional state.

Another issue regarding the unconscious mind is that if something is troubling us, we are often unaware of the incremental influence this concern has on our emotional state. Thus, we enter a negative state unconsciously and this state manifests throughout our physiology; we literally signpost to the other our concerns through our facial expressions, our voice tone, our tonal marking, our general body language, our breathing and even our complexion. People unconsciously read, or calibrate these signals and, because of emotional contagions, they can often turn away from us and disable any rapport-building opportunity. In effect they will find us disagreeable. They will sense our internal lack of rapport and will perceive our efforts at relationship building as being incongruent with our emotional state. Thus, managing our internal emotional state is a critical aspect of rapport building.

Closing thoughts

The American theorist Nancy Dixon (1996) has studied the ways in which people generate dialogue together so that they may think together. She notes that how people relate together is fundamental to whether they will be able to think together. I invite you to consider rapport-building processes as the prerequisite methodology you should enact in advance of dialogue. In fact, I do not think dialogical exchange is possible if people do not first enter a state of rapport. Rapport is a paradox. At one level the methods appear remarkably simple, yet it takes practice and skill to combine the methods together to build sustainable and meaningful rapport with others. Critically, rapport starts with oneself; its starts with the premise that we must learn how to be congruent internally in relation to our values, beliefs, and actions. From this congruence comes the state of mind that we need to project onto others our sincerity for building rapport. One can help the rapport-building process by accessing COACH state and, in doing so, one can leverage one’s inner resources in a maximizing way.

For change managers, rapport-building skills are essential. The ability to build rapport with your peers, your customers, your team members, and your line managers is a source of substantial competitive advantage that can provide you with the edge over others who are competing with you for scarce resources and rewards. Rapport is fundamental to change management situations as it is the essence of leadership. Rapport involves two or more people being comfortable with one another and identifying positively with each other’s agendas. People in rapport have considerable influence over one another and enjoy an alignment of perspectives and, so, are comfortable in their relationships

References

Carnegie, D. (1936) How to Win Friends and Influence People, Vermillion.

Dilts, B. R. and Delozier, J. (2000) Encyclopedia of Systematic Neuro-Linguistic Programming and NLP New Coding, NLP University Press.

Dixon, N. (1996) Perspectives on Dialogue, Center for Creative Leadership.

Isaacs, W. (1999) Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together, Doubleday.

O’Connor, J. and Seymour, J. (1990) Introducing NLP: Neuro Linguistic Programming, Mandala.