Nick Allard

Dean, Brooklyn Law School

Partner, Patton Boggs

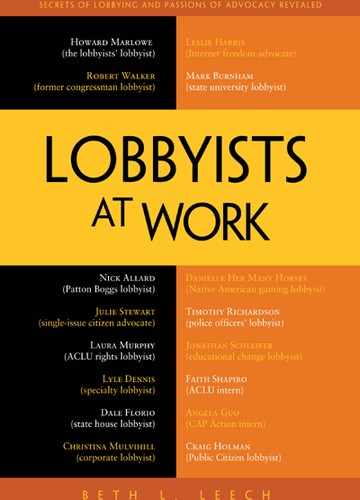

Nicholas Allardbecame the dean of Brooklyn Law Schoolin July 2012 and remains asenior partner at Patton Boggs, the largest firm in the country. The firm reported lobbying billings of $48 million in 2011 and gave more than $480,000 in campaign contributions during the 2012campaign cycle (evenly split between Republicans and Democrats). Patton Boggs’s clients come from almost every area of policy, from oil and finance, to cities and universities, to health and transportation.

Allard, who came to Patton Boggs in 2005, has repeatedly been named one of Washington’s top lobbyists. He is cheerfullyself-deprecating, full of names and stories and jokes, but throughout it is a fierce advocate for his profession. He has published numerous articles on lobbying, including one entitled “Lobbying Is an Honorable Profession,” in the Stanford Law and Policy Review, and a column in Newsweek in which he argued that “We Need More Lobbyists.”

Before becoming a lobbyist, he spent time on Capitol Hill as administrative assistant and chief of staff to Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) and asminority staff counsel to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary for Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-MA). He also worked at the law firms Kaye Scholer and Latham & Watkins, and he worked full-time on Vice President Al Gore’s election campaign.

Allard has an elite educational pedigree. His bachelor’s degree in public policy is from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, and hismaster’s degree is from Oxford University, where he was a Rhodes Scholar in 1976. After receiving his law degree from Yale University, he served as law clerk for Chief US District Judge Robert F. Peckham in San Francisco and for US Circuit Judge Patricia M. Wald in Washington, DC.

Beth Leech: Let’s start with where you began your career in Washington. I know that you went to Princeton, were a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, went to Yale Law School, clerked for a couple of judges, and then ended up in Washington. Was working for the Senate Judiciary Committee your first position in Washington?

Nick Allard: No. First I was in private practice. When I finished the second clerkship, my father-in-law said, “It’s time for you to get a real job.” I imagined the job opportunity at the law firm as the big fork in the road. I always wanted to be a lawyer.

Leech: And that comes out of your family experience?

Allard: No, it just comes out of an aversion to blood. Otherwise, I probably would have been a very good doctor.

A person could look at my résumé and think that I’ve jumped around, but in reality, from high school through college, studying overseas, law school, all of my jobs, there are two constant threads. One is that what I’ve done has always been connected to law, policy, and politics. Second, while I may have had many different positions and opportunities, there has been a consistent theme in terms of the people. Whether the people come with me or I’m joining people, I’ve had relationships where there’s a lot consistency. People sometimes say to me, “You have a big network.” In reality, I think that there are only about six hundred people in anybody’s world, and central casting just moves them around. I keep running into the same people over and over again.

Leech: So why don’t you walk me through some of those experiences?

Allard: I began in high school, walking precincts to get out the vote. Then in college I was at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. I’ve always had this combination of academically pursuing policy and politics. I was an urban affairs concentrator. My thesis was on NIMBY-type [Not In My Back Yard] issues and residential treatment centers for juvenile offenders.

Leech: Oh, very impressive.

Allard: Dave McNally and Jim Doig were my advisors. Jim Doig had one of the great comments of all time on my thesis. He wrote up three single-space pages of detailed comments about my thesis. I was a pretty good student, but I was also pretty busy. I was senior class president, honor committee chairman, blah, blah, blah. I worked a gazillion hours in the dining halls. Played rugby. My senior year I had two severely dislocated shoulders, and my arms were in slings. I had to get my classmates, twenty of them at one time, to simultaneously type, because we had this new technology at the computer center involving a mainframe computer and key punch. I wasrushing around right up to the last minute, getting it typeset and getting it bound and rushing, and rushing, and rushing. Doig’s comment was something like, “Page 217 is upside down.” Or, “Mr. Allard, knowing your work, I suspect that page 217 is the only page that’s correct and that all the other pages are upside down.”

At Oxford I studied PPE, which is politics, philosophy, and economics. That was the major for most of the American Rhodes Scholars who were heading into law or government for their careers. Then Yale Law School was the classic policy approach to law. The federal clerkships were also instrumental. The first judge I had, Judge Robert Peckham, was a wonderful man who loved politics. He was a chief judge in the Northern District of California, in San Francisco. I was there in 1979, a year full of fascinating issues. The first day I showed up I had to write, with the judge, an injunction in their ongoing monitoring of the San Francisco police and firefighters—in terms of which policemen and firefighters were going to be promoted to sergeant and which ones were going to be eligible for promotion.

Leech: I remember this case.

Allard: Then I came to DC and clerked for Judge Patricia Wald. The DC Circuit Court is a very special court because it hears all the appeals on regulatory proceedings. I worked on everything from oil drilling on the outer continental shelf, to environmental standards for clean air, to patent cases involving the birth of the computer in the digital era. I helped the judge write what is still the longest appellate opinion ever. You’re going to think that was my fault because I talk so much, but it wasn’t.

Leech: I see the connection and interest in policy coming in.

Allard: Then Reagan was elected president, so that foreclosed another opportunity, because I’m a hardwired Democrat. Otherwise, I might have gone right into the government, working for the Justice Department or something, but I wasn’t going to do that with a Republican in the White House.

So I went into private practice, working for a small Washington office of a New York firm, Kaye Scholer. I wanted to maintain my political and family ties in New York. My wife and I are both from New York. But by this time, we were already in Washington and my wife had this great job on the Hill, and we had twins. I had gone to Washington for one year for the clerkship and I ended up staying for thirty, which often happens.

Kaye Scholer was a very traditional commercial antitrust firm based in New York and it was opening a brand-new Washington office. I got a phone call from Ken Feinberg—whom you’ve probably heard of. He’s the “value of life” expert who designed the compensation systems for victims of 9-11, the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill, and the Virginia Tech shootings. Ken had been Senator Edward Kennedy’s chief of staff. He was opening the new law office and in that office was Senator Abraham Ribicoff—who had just retired, Allan Fox—Senator Jacob Javits’s former chief of staff, Alan Bennett—former counsel of the Food and Drug Administration, and Tom Madden—who had been the head of the LEAA, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration of the Justice Department. That was it: five partners. I was the one associate. I joined the firm and hitched my wagon to Ribicoff. He was such a great mentor. He taught me so much about the Senate and Congress, and about being a boss. I traveled all over the world with him and learned politics. He was a remarkable man.

Leech: What type of work was the firm doing in Washington?

Allard: Soup to nuts. It was very political but it was also law. Since none of those five new partners at this really traditional, hard-biting law firm had ever practiced with a law firm before, when something new came around, I was like the utility infielder. I got to experience many different things. First of all, they made me head of recruiting for the whole firm. I talked them into it.

They called me the managing associate. In the first year, we hired five appellate clerks, including Thurgood Marshall Jr. Ribicoff brought in Bob Cassidy as a partner. He had been the US trade representative’s counsel. Ribicoff’s assignment, because he had been the former chairman of the Trade Subcommittee, was to plant the Kaye Scholer flag all throughout the Pacific Rim. So I would travel with him. It was a great opportunity.

Leech: How long were you with the firm?

Allard: Three years. Let me tell you a funny story that shows one reason that the Washington offices of New York firms often fail. It’s because the New York guys never let go. One of Kaye Scholer’s huge clients had to oppose a temporary restraining order in a labor case. They had a hearing before Judge Barrington Parker in Washington, and lawyers from our New York office were going to fly in to handle the case. Judge Barrington Parker had the reputation of being unbelievably tough and refusing to tolerate fools. He was a terror to appear before.

Sure enough, there was a thunderstorm the morning when these New Yorkers were supposed to fly in on the shuttle. They were due in the hearing at ten o’clock a.m. They could not make it. So I get into the office at nine o’clock and they want somebody to go cover the hearing, and there was no one else in the office besides me who even knew where the courthouse was.

I had at least worked in the courthouse for a year. I knew what the process was because I had worked with federal district judge and chief judge. I knew what a TRO [temporary restraining order] was. But I knew nothing about this case—nothing. And the file was enormous.

Allard: So I’m in the cab on the way to the courthouse, papers flying every which way. I get there and I’m standing there and my knees are knocking together. The plaintiff—the labor union guy—gets up. I’m trying to power-read through what the case is about. I am not absorbing it. Barrington Parker is crucifying the labor union guy. I say to myself, “Oh no, I’m next.” So the labor union guy sits down, and I stand up and I say, “May it please the court, Nick Allard.”

He says, “Young man, let me get this straight. If I understand your position correctly, you are arguing A, B, C and so on. The relief you want is ‘T’.”

I don’t know where this came from, like some little angel on my shoulder. I said, “So moved.”

He says, “Granted.” And I never actually had to say anything about the case myself.

Leech: That is hilarious. You’ve been lucky in your life as well.

Allard: Most of the time.

Leech: You know how to take that luck when you see it.

Allard: So here’s fast-forward. Toward the end of my three years with the firm, Ribicoff calls me in. Feinberg’s sitting there, and they say, “Senator Kennedy called us and they need somebody to fill in on the Judiciary Committee staff. And so we told them we would send you.” There’s an important message in there—that’s one I’m telling law students. First of all, that’s why I had gone to this law firm.

Leech: To get into government?

Allard: Well, I knew it would give me those relationships, but it also gave me the experience that prepared me for going immediately into a senior position with Senator Kennedy. You also have to have the ability to feel confident and to plan, but when there’s an opportunity, go through the door. To me the opportunity to work with Senator Kennedy on the Judiciary Committee was great. The other lesson is that to get those great Washington jobs, you have to be on the ground there. Jobs are filled before they’re announced. That’s the way things work.

Leech: So, your advice to students is to get out of Brooklyn and down to Washington?

Allard: And once they get there, be present, work their network, get some experience, and don’t be afraid to fail. Don’t be afraid to seize an opportunity. If it doesn’t work out, do something else. There’s a lot of serendipity, but you’ve got to be in a position to make the luck. It’s not a formal bureaucratic process.

So I worked with Senator Kennedy. He was the most demanding, hardworking boss I’ve ever had. His staff was an assemblage of the brightest people I’ve ever worked with. I’ve got a great story about the job interview with Kennedy. If you get invited in to see the senator, you know that the staff has recommended that he hire you. So if you go in, you have to be prepared. If he likes you and he makes you an offer, you’ve got to accept, right?

At this point in my life, I had been around. I’d been a Rhodes Scholar, I’d worked campaigns, and I’d worked for the firm. I go in to meet with Senator Kennedy, and he and his legislative director Carey Parker are sitting in this big room that has, it seems like, twelve huge, dark oak doors. While I’m having this interview, staff are running in and out, doors are opening and closing, opening and closing. They put a document in front of him and he signs it, they put a photo in front of him and he signs it, and all the while he’s talking to me. That’s the scene. I have this out-of-body experience: he is larger than life. I’m looking at this enormous head and behind him is John F. Kennedy’s PT-109 medal, pictures of the three Kennedy brothers together, and he’s saying, blah, blah… He’s talking and at some point I realize he’s saying something about the line-item veto, or Roe v. Wade, blah, blah, blah. I’m looking at him, and I’m thinking to myself, “Mom. Not bad, huh? I’m doing pretty good here.”

Leech: Could be why you’re not processing.

Allard: I’m not processing. Suddenly he says, “So Nick, when can you start?” I blurt out something totally ridiculous. I said, “Well, my family and I are going to be on Family Feud and we have to tape that show in ten days.” Why would I say something so stupid, even though it was true?

Leech: It was true? This sounds apocryphal.

Allard: It was true. We were scheduled to be on Family Feud with Richard Dawson in California. The senator looked at me as if I had just suddenly and inexplicably started speaking French. He said, “Okay, when you get here, I want to see you the first day. I’ve got something I want to talk to you about.”

I stand up. I said, “Thank you very much. I’m really looking forward to becoming part of your team.”

He said, “Carey, would you show Nick out?”

I tried to regain some of my dignity. “I’ll find my way out. Thank you. I’m sure you guys have stuff to do.” I turn around and open one of the twelve doors, walk in, and I’m in the janitor’s closet. I open the door and I look out and the two of them are looking at me like, “We just hired this idiot?”

Fortunately, it was downhill from there.

That was my Kennedy story.

Leech: Your funny Kennedy story. So you worked for Kennedy, you were a counsel for the Judiciary Committee, and then…

Allard: Senator Moynihan’s chief of staff.

Leech: How did you end up there?

Allard: I was very happy with Senator Kennedy, and it’s very unusual in Washington to go from one senator to the other. But I walked around the corner of the office building one day and ran into Joe Gale, who was a classmate of mine at Princeton. Joe was Senator Moynihan’s legislative aide for tax policy. Joe looks at me and says, “Aren’t you from New York?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He says, “We’re going to be in touch with you. Moynihan’s looking for a chief of staff.”

Now, the reason he asked that question was that Moynihan went through chiefs of staff like toilet paper.

Moynihan was looking for somebody who had scholarly distinction. He was looking for somebody who had Senate experience. He was looking for somebody who was New Yorker, but not tied to Koch or Cuomo. There are plenty of people within those categories who had more distinction than I did. But there are very few people who match on all three requirements. So, that’s why that opportunity presented itself. For me, it was an incredible break to work for this distinguished senator from my home state, to be chief of staff at the age of thirty-two.

I had that job for a year and a half. I lined up the campaign, raised money for the campaign, ran it, and got through the Tax Reform Act. I often say that Moynihan got a decade of work out of me in a year. Then a new opportunity presented itself and the timing was good. My twins were eight and my youngest was three. A small boutique law firm focusing on health policy was starting up, and I was offered a partnership in the firm. It was the same people, minus Feinberg, who had been at Kaye Scholer’s office when I was there. It was a great opportunity, having really only been an associate for three years, to become a partner at a very promising, big-time boutique.

I was there for five years. I worked on health regulatory and health legislation at the state and federal level. And I started to get involved in this very big communications practice with some of my friends at Latham & Watkins, including Reed Hundt, who later became the FCC chairman. But I knew Reed before either of us knew much about communications. He was a top antitrust lawyer. He was also my next-door neighbor and our kids grew up together.

Latham was a firm that had offices in these big cities that are known for certain businesses, but it was never a part of that business. It just did its own traditional corporate work and litigation. So in Los Angeles, Latham was not a part of Hollywood. In Washington, it stood apart from lobbying and much of the government work.

Leech: How interesting.

Allard: That since has changed. But back then, Latham was representing lots of clients that had legislative and regulatory problems. And Latham would refer them to me, and more and more were related to communications. I became a one-man army of communications, doing all of the government relations and legislative workthat Latham referred to me. Two things happened simultaneously. I outgrew the boutique and Latham said, “This is ridiculous. We should just have Nick come in with us.” So, I moved to Latham and they asked me to not only handle the government relations work, but to build up their government relations practice, which I did for twelve years.

Then in 2004, I was recruited by Patton Boggs, which is the number-one public policy lobbying firm in the world. And since nobody has this level of lobbying except the United States, you could also say it’s the largest in the galaxy.

I had many friends at Patton Boggs, and frankly, I had this image of them being sort of cowboys, more roll-around, warrior-type lobbyists. They approached me and I was very impressed with a couple of things. One is that they were in the process of moving into the next century and becoming a much stronger firm. Also, the opportunity was almost irresistible. They realized they needed reenergizing. They wanted me to come in and help lead the practice. So I did it. I went over there and I had eight really successful, tremendous years.

Leech: So you remain a partner in both the New York and Washington, DC, offices of the firm, but when you were at Patton Boggs full time, what types of clients did you primarily represent?

Allard: The variety of the clients is very large. Many of them are Fortune 100 companies in communications, online services, health, and energy.

Leech: Are those the fields that you, in particular, tended to focus on?

Allard: I’m accused of being an expert in health, communications, and Internet law. That’s because I’ve written and published and do more and more work in those areas. They are areas of enormous change, and when there’s enormous change, the relevance of existing laws and rules is challenged. So, the question of what should the law be becomes very relevant. It’s not surprising that I’ve developed a lot of experience in those areas. In some ways, what I do is generic, like a litigator. I know how to argue a case. But it’s very important to have some sort of expertise.

I’ve worked across the board: on international projects, the appeal of a regulation, acting as arbitrator in a telecom dispute, or arbitrations overseas. I worked on the Telecom Act of 1996, then the one hundred and eighty-eight regulations to implement that act, and all the issues since then. I also have worked for nonprofits, represented major universities, and had some very significant pro bono projects. One of those cases was advocacy related to the Dream Act.

Leech: Who was the client in that case?

Allard: I had one client whose name was Dan-el Padilla Peralta, who was a salutatorian for Princeton University. He was brought here as an infant from the Dominican Republic. His father left and his mother was a drug-addicted street person. He and his brother bounced around from foster home to foster home. He ended up with a couple who were acting as his foster parents when he was a young teenager. He became fascinated with the stories in the books that they had about the Romans and the Greeks. He became one of the leading classic scholars at the age of twenty or twenty-one. He graduated and won a scholarship to study in Britain, at Oxford. The Department of Homeland Security, in its wisdom, said, “Well, congratulations. You can leave, but you can’t come back.”

Leech: In your advocacy on this, and in your advocacy for him, what sorts of activities did you do? How would you approach an issue like this?

Allard: You organize students—some from conservative Christian colleges in the Midwest, people like him who had these incredible stories. By the way, he had no idea that he was an undocumented illegal alien until he applied for a summer job to help pay for college.

Leech: Oh, no.

Allard: Right. There’s no concept of fault, since they were brought here as infants. Plus they are success stories. These are the kind of people that we don’t want to push away. We should want these people to stay with us. To advocate for these young people, we took them around to congressional offices representing the districts where they were from or where their universities were. We made the case. We tried to work out the politics, the very tricky immigration politics. A lot of advocates, if quoted, would deny this, but there are advocates of immigration reform who don’t want the Dream Act to be passed freestanding because there is more support for the Dream Act than for other aspects of immigration reform.

The immigration advocates are saying, “We don’t want to do this piece. We want to do our comprehensive package.” We tried to negotiate those differences. Then we were involved in drafting and negotiating, trying to hear what people’s concerns are, and then addressing that. For instance, saying: “Since there is a problem in terms of what’s the path toward citizenship, what if we extended the waiting period before citizenship another six to eight years?” We would work out the conflicts, listen to all of the competing but legitimate interests. That was one of my recent cases with very compelling stories. We were not able to get the Dream Act passed at that time, but we were still able to help those particular individuals, including Dan-el. They were allowed to stay. That was fulfilling.

Leech: That’s great.

Allard: I also represented an Air Force Academy cadet in a pro bono case. It was a good case for me because I have a lot of honor committee experience because of my work for Princeton. This cadet was number two academically in her class and eight days short of graduation when she was kicked out on trumped-up honor committee charges. One of the members of the honor committee was also the fellow she formally accused of sexual harassment. She had been subject to a sexual attack.

We had statements from faculty saying that there could not be an honor code violation because it was a take-home group exercise. What the Air Force eventually got her on was not the honor code violation. The Committee kept her in a room for an unreasonably long period of time, questioning her until she was exhausted, and because her statements were inconsistent, she was said to be lying, which also violates the code of conduct.

She was told she wasn’t going to graduate, that she had to pay back her full four years of tuition to the government within the next three months, and she now had to serve as an enlisted Air Force person. All she ever wanted to do was fly. Even though no honor committee case had ever been overturned, the merits of her case and the sheer weakness of the counter case gave us great confidence that we could overturn the decision.

The family was adamant that her case was part of a larger problem. They wanted to take on the whole Air Force Academy. I kept saying, “That’s a much heavier lift and you don’t understand that you can win on your case— just you. You don’t have to turn the entire Air Force Academy and the Air Force upside down.” But when we got into her case, we found such an organized system of abuse, protection of perpetrators, and punishment of the victims that we had no choice. Her case helped to precipitate a much broader scrutiny of the academy, and I’m sure you’re familiar with it from media reports.

Leech: That was the thread that pulled everything else apart.

Allard: And she graduated. She didn’t have to pay. In the history of the Air Force Academy, no honor committee case had ever been overturned—that’s what we did. Unfortunately, even though she would have been eligible, she had missed flight training with her cycle and it would have been very difficult for her to go back. She also was frightened and believed her career in the Air Force was finished. So, she never actually got her chance to get her wings. But the Air Force Academy has become a much better place because of her.

Leech: As a lobbyist, how do you begin your work on a tough case like this?

Allard: We pursued and exhausted the academy process and the military process until we hit a dead end. We went around congressionally. Then we started generating letters to the secretary of defense and the secretary of the Air Force. I started a press and media campaign. Eventually, other cadets started coming out with their stories. It kind of snowballed. Her case was one of the first public cases.

What a lobbyist does is problem solving. For the best lobbyists, it’s not necessarily any one set of actions. A good lobbyist looks at the problem orchallenge, or whatever it is that a client wants to accomplish, and the lobbyist analyzes it and comes up with a solution. It’s not as if all lobbyists have a Chinese menu of things that they do, and that a lobbyist just applies those, picking randomly from that bag. A good lobbyist has to think creatively think about how to accomplish what needs to be accomplished.

Leech: How do you do that? Can you walk me through how you analyze a situation?

Allard: A good lobbyist has to try to become an expert about every aspect of each project. A good lobbyist has to learn their business or learn their situation, or learn their facts and understand them. A lot of times it helps to have the collective wisdom of other people, it’s a collaborative process in different perspectives. And here I am not talking about all lobbyists but people who are working as lawyer-lobbyists at the level that involves problem solving.

I tell you what good lobbying isn’t. There are a lot of times that lobbyists are marketing their relationships, so it doesn’t matter if you’re an Air Force Academy cadet or you’re somebody with their arm missing. They’re going to say: “Because I worked with Senator so-and-so, let’s have a meeting with Senator so-and-so or let’s have a meeting with these three other people I know.” Or the lobbyist does one thing—public relations, for example—and applies that to every problem. Really good lobbying is figuring out what needs to be done to solve the problem and then accomplishing that.

Leech: Could you break down your process for doing that?

Allard: I’ve broken it down this way, and I’m going to give this to you, free of charge.

Leech: Free of charge.

Allard: I had planned to send this out as an op-ed to say as I’m about to go to the academy, “Here’s a teaching moment.”

[Clears throat.] The Seven Deadly Virtues of Lobbying:

There are three hundred fifty million experts in the United States, more or less, about our government. Most of those people have a very negative view about what lobbyists do. For example, they may believe that lobbyists buy results or that lobbyists are corrupt. But in reality, that is not the case. First of all, it can be shown that money does not buy results. As for corruption, professional lobbyists comply with the rules because that’s essential for them to have a career and a business.

What do lobbyists do? The first thing lobbyists do—and this is the best understood function—is provide information to the government. That gets all the attention, but I think it is the least important thing lobbyists do. Now sure, it helps to have a professional advocate. We have a saying: “Anybody who represents themselves in court has a fool for a lawyer and an idiot for a client.” The same applies even more in the political arena. There are a million compelling stories and needs and wants competing for the attention of lawmakers and regulators. Just to be heard over the noise takes professional advocacy. But members of Congress and other government officials have many sources of information. They don’t just have to rely on lobbyists. They have the Congressional Research Service, they have staff, and they have public domain. If there were no lobbyists, they would still be getting information.

Second, and even more important, is that lobbyists provide information to their clients. They provide information, for example, in the intake discussion. When a client presents an issue, good lawyer-lobbyists will be able to tell the client whether it’s doable or not. They will explain to the client that maybe if you try to get something slightly different, you could accomplish something close to what you wanted.

I’m talking about the good lobbyists, not Jack Abramoff. It makes me bridle when people call him a super-lobbyist. Because he wasn’t a lobbyist. He was a crook. He was getting paid for things he couldn’t deliver. The good lobbyists will not take credit for the sun coming up, and they will also say when they can’t do something. They will say, “That tax change has no chance of getting enacted this year.” And, “By the way, what is the public policy argument for what you want done?” Because unless there is a compelling policy argument, members of Congress aren’t going to do it because it’s not sustainable.

Number three: lobbyists provide information about the other side. There’s competition. It’s an adversarial process. They keep the system honest by making everybody check their math. This assumes transparency. It assumes that you know what’s going on. Sunlight is one of the great disinfectants. Professional lobbyists who play by the rules don’t fear transparency. They want it because they want to have the opportunity, like a lawyer in court has the opportunity, to challenge the other side. This is why one of the most effective techniques of being a lobbyist is to say to a decision maker: “Here’s our case and this is why we like it. And this is what the other side is going to say, and this is why you should discount that.” The lobbyists for each side hold each other accountable. That’s number three.

Number four: lobbyists hold the government accountable. This may be the most important thing. This derives from the right to petition in the First Amendment. Lobbyists sometimes mistakenly say, “The rules of lobbying violate my First Amendment rights.” The lobbyists don’t have any First Amendment rights. The First Amendment rights are of their clients. But every court that has addressed the issue throughout history has said that the right to petition includes the right to do it well. That means the right to hire somebody, because lobbyists can help. Holding the government accountable is not convenient to the government.

Number five is something that, once I say it, will be obvious. But it’s actually not what’s in people’s minds. Professional lobbyists comply with the rules. The reason for that is if you don’t comply with the rules, not only does that give your opposition a cheap argument, but it will embarrass you and your client and you won’t get work. Ironically, the bigger the company, the more the company is interested in compliance. A related point is that the rules for lobbying—including things like the “toothpick rule” for what food a lobbyist can serve to members and staff—are so complicated that

a layperson could not be expected to comply. The rules are not common sense. So clients need professional lobbyists to make sure that when they’re making their case, they’re doing it in a way that’s appropriate and complies with the rules.

The sixth thing that lobbyists do is make sure the other guy is complying with the rules—playing fair and honest. Now, one of the standard playbooks of being a lobbyist in an adversarial situation is to check the lobbying registration of the adversary and start making noise if they’re violating the rules. You think that Jack Abramoff or any case of scandal was discovered by the Justice Department? Heck, no. It was the other side that ratted them out. Professional lobbyists keep the system honest.

The seventh thing is that good lobbyists provide a much-needed sense of stability, accommodation, and mediation that leads to solutions. When there are uncivil partisan quarrels in Congress and in the government, lobbyists can be back-channel messengers, come up with solutions, talk to people, reduce the temperature, and figure out how overcome the impasse. That’s what professional lobbyists do. You can accuse lobbyists of many things, but I can’t think of a single lobbyist who is rude or makes uncivil comments. Those are the seven things lobbyist do, and here’s a case that shows that.

Clients approach a lobbying firm because they want to accomplish something. As a lobbyist, you have to listen, then adjust the clients’ expectations of what they want and figure out how to actually get it. So, say, hypothetically, that a major pharmaceutical company has a life-saving drug that it holds exclusively and it’s not ready to lose its exclusive license and let the drug go generic. The company will lose hundreds of millions of dollars when that happens, so every moment that the company can keep its exclusivity will enable them to continue to charge higher prices and make more money. So the people at the company want you, the lobbyist, to get Congress to extend the license.

Once you, the hypothetical lobbyist, start having a conversation with the research team, the first thing to say say is: “Put yourself in the shoes of any member of Congress. Why would any member of Congress or any secretary of Health and Human Services [HHS] want to make it possible for you to charge sick people higher prices?” First of all, you have to get the client ed to realize that they are not sympathetic. By the way, sometimes that’s not the easiest thing to do.

Leech: I bet.

Allard: Then you start to learn about the public policy merits of the case for extending the license. You talk with them and talk with them and talk until you understand the product and the science of it and everything else. Until you realize, “Wait a minute. This is interesting. This product is the leading product in its field in the world. However, it has unfulfilled potential. The benefits now are actually a fraction of what the benefits to the entire population could be if more research were done.” You also learn that this product is so devastating in its present formulation that some people die from it. If there were more research, other formulations could be developed that would allow more people to take it with lower risks.

Why won’t that research get done? Well, if the drug goes generic, there would be no incentive to do the research. In addition, no company would be willing to go through the laborious, time-consuming, and very expensive process of getting the United States Food and Drug Administration [FDA] to agree that any new formulation is safe and effective. The financial incentive would be gone.

Once you have an idea, you check it out with some scientists. Then you explore the patient population and talk with their representatives. You ask, “What do you think about this?” They reply, “We think it actually makes some sense.” Then you float the idea with Health and Human Services and the White House, and you inform members of Congress about the plan so they know you, genuinely—that is a key word—are trying to help. Then you have another conversation with the company and say, “This is what we are going to propose, and everybody supports this. You get an extension of your license for this many years, but you are going to commit each year X millions of dollars on research.” Then you might say, “Oh, and by the way, client. You don’t get to choose what research is done, so that no one can say that you’re just picking what’s commercially most valuable. You’re going to commit that money to a National Institute, and it will decide where the money goes.” Guess what? Saying this to a corporate executive is like breaking wind in a board meeting.

You also tell them, “By the way, you’re going to agree to reduce your prices. It’s not going to be the huge reduction that you would face if the drug went generic, but the price will drop a little the first year, then a little more the next year, and so on.” And lots of more complicated details—but that’s the gist of it. Then you say to them, “The White House, HHS, the members of Congress—everybody seems to agree with us. But we’re going to put this proposal in the Federal Register to give public notice and invite comments—not just have it announced.” The reason for that is we don’t anybody who’s been waiting out there for the drug to go generic to have a case that they were denied due process. Let them come in and make their arguments. Otherwise, there will be companies tying this up in litigation on procedural issues even though the merits are compelling and advance the public health.

So, that’s what good lawyer-lobbyists do. The result is that it’s announced in the Federal Register. There are ferocious comments by other companies. But patients think it’s great, medical researchers think it’s great, the government thinks it’s great, and members of Congress decided that it’s great. Not one lawsuit is filed against it because it was all open, solid, based on good science and health policy, and fair. Not quite the silver bullet, simple phone call, political fix image of lobbying. Rather, an arduous, detail-driven, long-haul, nuanced, law-based endeavor. Now here I should emphasize my hypothetical is dramatized to convey my point. Its compiled based on experiences and situations I’ve known about, but any resemblance to an actual project and real people is purely coincidental.

Allard: And I oversimplified. Actually, extensions of this kind can happen in bites over several years, and one might be an executive order and another required passing some legislation. It’s multiyear. It’s multiarena. It’s not simply because a lobbyist knows the secretary of HHS or the FDA commissioner and picks up the phone to persuade them. People have the impression that there are these silver bullets. That is rarely the case. One of the reasons for that is well known in Washington: anything that is done can be undone. If somebody pulls a fast one, persuades a member of Congress to slip something into a bill late at night—like an extension for exclusive license—it gets in the press the next day, as soon as somebody realizes this is what’s going on. People are embarrassed and it gets the client nowhere.

Leech: When we were talking earlier, you mentioned the influence peddling and the idea that the public has that Washington is for sale. What do you say to those people? What’s your explanation for why an organization like Patton Boggs gives something close to half a million dollars in campaign contributions in an election cycle?

Allard: I don’t have a great explanation for that. I have always been engaged in politics, so part of the answer is that we are people who enjoy politics and want to help. I only give to people I sincerely believe in, and mostly I only give to Democrats. The only Republican I can remember giving to is my college roommate Bill Frist, who was Senate majority leader. I knew him when he was a Democrat. He’d be really mad if he knew I said that.

That’s only part of the answer—that we’re involved in politics and that we like it and support it. There’s not a really satisfying answer. That is a very fair point. Still, I really don’t believe that you get anything for your campaign contributions. What I do think is that the reason the public feels that the whole system is corrupt and that money buys results is because there’s so much money and so much campaign financing. Not that it really corrupts the system.

Leech: So you see it as more of a problem of perception.

Allard: The real scam is that the members of Congress and the president have to spend so much time raising money that it interferes with their ability to function. That’s the big scam. It’s a big scandal that when observers walk into the gallery of the Senate, overlooking the world’s greatest deliberating body, there will only be two or three senators most of the time. What’s really shocking is the senators are all someplace else, dialing for dollars around the clock. That’s the real scandal.

The problem members of Congress always have is that they really believe they need the money to campaign. So they feel that they have to convey to contributors that they get something for those contributions when, in reality, no member of Congress who’s going to serve and be there long is going to make a decision based on a campaign contribution.

I’ll clean this story up for you. I’ve been politically incorrect so many times—I’m still going to clean this up. You know that Jessie Unruh quote?

Leech: I don’t think so.

Allard: He actually stole the line. Unruh was a legendary state senator in California. He said about lobbyists: “If you can’t take their money, drink their booze”—and here’s where I’m cleaning it up—“and dance with their women, and still vote against them the next day. You don’t deserve to be and you won’t be in the legislature for very long.”

Here’s the other perverse thing about campaign contributors: I saw it happen often with people who are very close to me. Presidential candidates or even senatorial candidates encourage people to keep doing this fundraising stuff. These people who fundraise often do it because they’re successful in life—they’re really great, talented people. They work their rear ends off to raise money because they believe in a candidate, a cause. Then they become marginalized afterward because now they are just the money people. They thought they would be ambassador or secretary of commerce or be able to serve in government, but now they are marginalized.

Leech: Is that because politically it would look bad to be too close to the fundraisers?

Allard: If I suggested to three quarters of my partners, “Let’s unilaterally stop making campaign contributions”—they would not agree to do it. People do not agree with me on this. They would say, “How would we operate? We’ve got to be players.” I’m just highly skeptical about the value of the contribution. The way a lobbyist prevails in a case is by being the best-prepared, smartest person in the room, and having the most compelling case.

The other thing that helps support my point is that I only give to Democrats, I only vote Democratic, and I volunteer my time only to Democrats. I have never had a problem working with the Republican administration or a Republican member of Congress. Well, with two exceptions: you can guess who they were. I just got somebody else to do the meeting. My party didn’t matter. Now maybe things have been changing in that direction.

Leech: Your firm also donated to both parties.

Allard: Yeah, of course, but nobody asked me about my partisanship. Nobody asked me that. It’s not about me, it’s about who is it that I’m representing and why a government official should be interested in them.

Leech: Before we end, could you walk me through what your day was like when you were still at Patton Boggs in DC?

Allard: This is my day. And the funny thing is, it’s the same at the law school. I get up at the crack of dawn to do writing. It’s the only time of the day I can do it. Part of what I write is the list of things I absolutely have to do that day. Then I hit the office, after going to the gym.

I then spend the whole day doing triage on whatever has come over the transom. I’m reviewing exciting opportunities, dealing with crises, trying somehow to get back to the five critical things that had to be done that day. The whole day is dealing with the unexpected and performing triage on the unexpected, so that I can get done what really needs to be done. That’s what my days are like. There is no normal or typical day. Really, there is none. I would say—and I’m making this number up—seventy-three percent of all statistics are made up on the spot. But I would say eighty percent of lobbying is preparation—through conversations, research, writing, and brainstorming—and twenty percent is actual advocacy. If I’m off, I’ve erred in saying that the advocacy part is as big as twenty percent. It might be nine to one.

When people think of what a lobbyist does, they forget about the preparation. Maybe I’m doing my colleagues a disservice by making the job seem less sexy than they think it is. But there’s a lot of hard work in preparation and research. Don’t let that secret out—it may damage our reputation forever—but that’s the case. People have this sort of image of the bag-carrying, bourbon-swilling, philandering, duck-hunting magician that can make Washington dance on a string like a puppet and gets by with a phone call or a single meeting. That caricature never really existed. But to the extent that it did exist, it’s now in the La Brea Tar Pits with the other extinct mammals. It may have been the case in the sixties or early seventies when there were few decision makersand so there were few people that you had to know to get anything done. But there’s been such a dispersion of power and there have been so many good-government types of rules enacted that it’s much harder to get things done. Today it requires more work and a more professional lobbyist.

Leech: Very interesting. I cannot tell you how much I appreciate your taking the time to talk about this. It’s going to be a great chapter.

Leech: It is a novel. The novel of Nick Allard. And as we near the end of the chapter, I should ask you about your new job as dean of Brooklyn Law School.

Allard: I’ve always had a foot in higher education, as an author, teacher, member of boards, member of search committees, or trustee. I was finding increasingly that the things that interested me the most were related to higher education. I also had already done what I needed to in those eight years at the firm. I already had eight successful years—number one every year. During my time there, the firm made a lot of changes through the compensation structure, more teamwork, more structure to the department, and fantastic hires. The firm continued to do that and make a lot of money. I was looking for an opportunity to put something back and to make a contribution to something exciting. Brooklyn was irresistible because, as GQ just said, “It’s the coolest city in the world.”

Leech:Très Brooklyn is French for being hip.

Allard: And our law school is in a very exciting position. So it was irresistible to come on board and be part of the only law school in the most exciting place on earth. The Above the Law website recently listed Brooklyn Law School [BLS] as one of the top five law schools in the country that deserve more attention. We have a huge potential to build on. There are challenges for law schools and new lawyers today, thanks to a soft job market and high student debt, and our school is responding. BLS has one of the most rigorous clinical and externship programs in the country. We’ve created a “business boot camp” and expanded a program on running your own law firm, so that students learn the skills they will need once they graduate. But more importantly, we are working to train students to be creative problem solvers. My lobbyist-lawyer skills have always been about problem solving: being curious and figuring out how things fit together and building consensus, and that fits our approach at Brooklyn Law School.

And remember what I told you earlier about central casting? Ken Feinberg, whom I worked with at the start of my career, will be the speaker at my first commencement at BLS. The continuous loop holds.

Leech: The jobs you’ve had throughout your career really do all fit together.

Allard: Do you speak or read Chinese?

Leech: What’s up with China?

Allard: Here’s a copy of China GQ.

Leech: Oh, hilarious. You’re in the magazine.

Allard: The latest issue is about interacting with the government.

Leech: That is great.

Allard: Everybody says, “You want to get this translated?” I said, “Hell no. I want to tell everybody what it says. It says that I’m the most persuasive, attractive, irresistible….”

I was actually really irritated. I called the editor up and I said, “You used the worst picture. I look like a fat slob.”

And they said, “Hey listen, in China appearing well-fed and prosperous is a very impressive and good thing. People are very respectful of that.”

I said, “Now you’re making me feel even worse because you’re not denying it.”

Leech: You know, I think the picture doesn’t look that much like you.

Allard: Thank you. You’d make a great lobbyist!