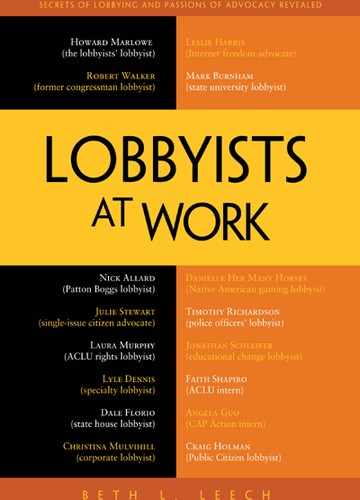

Mark Burnham

Vice President for Government Affairs

Michigan State University

Mark Burnham is vice president for governmental affairs at Michigan State University. He is based in Lansing, with responsibilities that involve local, state, and federal affairs, but before his promotion in 2011, he worked full-time in Washington, DC, as MSU’s associate vice president for governmental affairs. Before coming to Michigan State, Burnham was director of federal relations for research for the University of Michigan.

Close to 100 different universities maintain their own lobbyists and offices in the Washington area, and many more than that hire lobbying firms to represent them. MSU reported spending $340,000 on lobbying expenses in 2011.

Burnham has bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Michigan and a law degree from Boston College Law School. Before going to law school, he spent four years as a staff member for Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-OH). After earning his JD, he worked for the law firm Jones Day and then for Lewis-Burke Associates, a lobbying firm whose clients include many universities.

Beth Leech: How did you become a lobbyist? How did you enter this line of work?

Mark Burnham: I knew I had always wanted to go into public policy. Even before I finished my undergraduate degree, I knew. I didn’t communicate that too well to my parents, though. At the end of my junior year, I had an internship set up in Washington, and I was moving my stuff back to my parents’ house. My mom and dad sat me down and said, “We’re a little concerned because we don’t know what you’re going to do.” I looked at them and said, “Oh, I guess I didn’t tell you.”

I laid it all out: “I’m going to move to Washington and do this internship. I’m going to work in one of the House Office Buildings and start building my career.” Dinner came and their jaws were sitting on the table. I just started eating. It’s funny now.

Leech: What was that first internship? Where did you work?

Burnham:I worked for Congressman Dennis Hertel. I had a wonderful summer. It was a tremendous experience and I got the bug, that so-called Potomac Fever. I knew what I wanted to do. I finished my senior year and I started applying. I sent résumés all over Capitol Hill. I was applying for jobs that only existed in six buildings in the entire United States, and I got a lot of rejection letters. I have enough to paper a wall. For some reason, I kept them. It’s kind of entertaining to read them because I now know most of these people.

Leech: You kept all the rejection letters?

Burnham: I did, though I am not really sure why. I had gotten a rejection letter from Representative Marcy Kaptur, but I kept pounding the pavement, walking door to door in Capitol Hill. I went to Marcy’s office and I said I appreciated the courtesy of her response because not everybody bothered to respond. I was curious if they knew of any other jobs that might be open in the area that I could apply for. The guy behind the desk said, “Well, actually, I’m going back to grad school, and the office didn’t know that when we rejected you.” So, he took my résumé again, and they had me come back to interview. Then I drove to DC to do an interview and the chief of staff had been called to a meeting in the district office, which was in Toledo. So I went to Washington in order to have a phone interview with the chief of staff, who was in Toledo.

I was hired and started at the front desk, which is where most Hill staff start their careers—opening mail and answering phones. By the time I left, four years later, I was a senior Appropriations staffer who had also worked on issues related to NASA, Veterans’ Affairs, and a variety of other topics. Every legislative staffer has a list of about twenty things that they’re responsible for, far more than most people would imagine.

At the end of the four years, I decided to go to law school. What convinced me in part was that Marcy wasn’t a lawyer. She’s an urban planner by training. She had a couple of cases where she was really struggling because she didn’t have an attorney on staff and she wasn’t an attorney herself. I learned from that and decided, “I think I want to know what the law’s all about.”

I went to law school with the idea of coming back into public service. The people and the program at Boston College really fit me and I was one of those odd ducks who really enjoyed law school. After graduating, I knew I wanted to get my feet wet in actual court work first. It took a little while to find that first law job, in part because some employers didn’t believe a twenty-something could actually have had the scope of responsibility I had had on Capitol Hill. Eventually, I spent about three years doing litigation for Jones Day, which at that time was still Jones, Day, Reavis, and Pogue. I was basically a traveling attorney doing major litigation in Minneapolis, Florida, and all over the place.

Leech: Any particular area of expertise in litigation?

Burnham: I was staff attorney doing document support for major product liability litigation, but I knew I wanted to continue doing public service. You do law firm work for a while and then you get really tired of it, at least I did. I reached back to a colleague whom I had met my freshman year of college. He had worked for a member of Congress, for MIT, and for the University of Michigan.

He helped connect me to a small niche firm called Lewis-Burke Associates, which was run by a woman whose name was April Burke but her maiden name was Lewis, so Lewis-Burke was all her. I had an interview early on in my search, but it didn’t really go anywhere. It turns out that I was a little early for her. She wasn’t ready for a new person.

A few months passed. I got married, went on my honeymoon. I came back from my honeymoon and two weeks later, I got a call from the Lewis-Burke office saying, “Are you still interested in a job in this field?” They had a staff person leave. Once again, first rejected, then I got in.

Leech: You stayed in the game.

Burnham: It seemed to be a pattern at the time. I started working for April and one of her main clients was the California Institute of Technology—Caltech—so my experiences working on NASA appropriations when I was back on the Hill became very relevant very quickly. I still had contacts. One of my really good friends from early days on Capitol Hill (when we were both maintaining our office computers) was now the senior Appropriations staffer for the chairman of the subcommittee that funded NASA. He helped me understand the details of the NASA budget, and that led to me being able to speak intelligently about the budget issues with the client. So that’s the story of how I got into lobbying.

Leech: A lot of the clients that you worked with at Lewis-Burke were universities.

Burnham: Yes. Lewis-Burke is a niche firm that represents universities and science consortia. It was either directly working for the university or the science consortia, which are almost all university-based. For example, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is managed by a group known as the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research [UCAR], is really a group of about seventy research universities around the country. As a result, we ended up doing a lot of work with the federal science funding agencies like NASA or the National Science Foundation, as well as with Congress.

Leech: You went from Lewis-Burke to Michigan and then Michigan State. How does working a lobbying firm as a lobbyist differ from being in-house the way you are now?

Burnham: There are significant differences and advantages to both. Let’s back up and look at lobbying. I think there are two types of lobbying. One is based on relationships that are there because you know the legislator or their key staff. You might have known him or her when you were growing up, or you worked for him or her for a number of years, or some other affiliation like that. You’re not really substantively based. You’re relationship based. A lot of lobbying firms rely primarily or exclusively on that kind of lobbying.

The other type of lobbying is when you really come up through a particular area or field and you become very knowledgeable in that area, and then you use that knowledge to develop the relationship, because that subject area happens to be important for that member of Congress. Lewis-Burke is a little different than your typical lobbying firm. Lobbyists there had some relationships that they had built, but we did most of our lobbying based on substance.

At Lewis-Burke, we had a depth of knowledge about the politics of higher education and science funding, but a less robust understanding of the client, because we represented many clients. I might have a meeting with an Appropriations staffer, so first I have on the Caltech cap, and then I’m wearing the UCAR cap, and now I’m wearing the University of Cincinnati hat. I was very deep in the policy and had in-depth relationships in Washington on all of those issues. I didn’t necessarily know any given university nearly as well as I do now, nor did I have to deal with things other than funding for those universities’ research agendas. That said, I probably did some of my best policy work while I was with Lewis-Burke, since it is one of the few really skilled policy shops working in the sector.

When I started representing the university as a whole, I had to develop a much more comprehensive understanding of the politics within a university and the many roles the university plays in the world. When I first started at the University of Michigan, I worked directly for the vice president of research, so in theory, I still was limited to the research portfolio. Even then, I ended up getting a much broader understanding of the mission of the institution, a much better understanding of the institution itself. For example, when I worked for UM, I was the face of UM in Washington (not the only one of course). This meant I had to be prepared to discuss everything from athletics to admissions issues—even when those weren’t my area of responsibility. On campus, I didn’t just report to one point of contact—but now I was a part of the office and was representing the Vice President for Research with the faculty. That creates an entirely different dynamic than when I was merely a consultant to the university.

I went from there to MSU’s Washington office, and then I had to deal with the full breadth of the university’s activities. Now I’m a vice president of the university and I’m located on campus, rather than in Washington, and I have an even more in-depth relationship and understanding of the institution, and the people, and the direction the institution’s going. I don’t quite have the same level of engagement with the agencies and the Congress as I did when I worked as an outside lobbyist, although of course, I still retain a lot of that knowledge and I work to keep those relationships fresh.

Leech: How long have you been back in Michigan?

Burnham: Two years in February 2013.

Leech: Let’s talk a little bit about why a university would need a lobbyist.

Burnham: First and foremost, because places like Michigan State or Michigan, or even Caltech, are institutions that are so large that they become some of the biggest employers in their areas. At MSU, we have our own power plant. We’re a two billion–dollar entity with sixty thousand students and staff, so we’re very much like a small city. There isn’t an area of federal, state, or local government that doesn’t impact the university or where the university cannot play a role.

On top of that, at a place like MSU, the university receives about $295 million a year in base support from the state of Michigan, $300 million a year in federal research dollars, and another $400 million a year in financial aid that goes to the students.

There’s a lot of need to manage the relationships with the congressional delegations, the congressional committees, and the federal agencies—whether it be because of funding issues, immigration status for faculty or students, regulations about where and how to store hazardous chemicals that might be used in scientific, or agricultural, or power plant operations, or how the university deals with emergency response if there is an active shooter situation on a campus of fifty thousand students.

A university also might need a lobbyist to keep on top of proposed changes in labor regulations or regulations that affect fundraising efforts, such as changes in tax laws that deal with charitable contributions. These are just some of the issues that come to play on a regular basis.

A lot of my job now is about trying to keep government officials and the public informed. For example, a lot of people think state universities are still funded the way they once were back when they went to school, and assume that universities have been getting funding increases. Public universities nationwide used to receive about seventy-five percent of the cost of undergraduate education from their states. However, today, state financial support for MSU has declined to twenty-two percent, and if you look around the country, some schools are as low as four percent. The world has changed in terms of public financial support for public universities. They’re a lot more dependent on tuition dollars, competitively awarded research dollars, and federal higher education financial aid dollars.

Leech: At this point, you split your time between attention to Lansing and attention to Washington. How do state and national lobbying differ and how are they the same?

Burnham:Whether or not a university has permanent staff in Washington depends a lot on how much research funding the university has, because general higher education funding is primarily dealt with every five years during the higher education reauthorization, but research funding is an annual process. The more research dollars you have, the more likely you are as an institution to have somebody full-time in DC.

At MSU, I’m lucky to be able to have somebody in Lansing who is doing the day-to-day state lobbying work and I have somebody in Washington who is doing the day-to-day federal lobbying. At the state level, where we have term limits, there are a lot of elected officials who are very new and have very little base institutional knowledge of the university or even of the legislature. You have to do a lot of educating quickly. It used to be that legislators would have enough time to learn these things. They really don’t these days, and there is very little incentive to bother.

Congressionally, we don’t have term limits on our elected officials and that allows us to have members of Congress who stay long enough to really start to understand where we fit in the process. A lot of the difference is that I don’t have to retread the same ground on who we are and why we exist, but I can get more into the substantive details. It’s harder to get into that level of detail at the state level.

Leech: How many people are in your office?

Burnham: I have two professional staff in Washington, myself and four professional staff here in Lansing, and a couple of support staff.

Leech:Let’s slow down a little bit to talk for a while about a recent issue that you’ve been involved in, because I think it might help if we went step-by-step-by step through how it arose, what you and your office did to try to address it, and to explain to the general reader how something like this comes about and the sorts of things a lobbyist actually does. If you can think about something you’ve worked on recently, let’s just pick it apart for a minute.

Burnham: The most common issues we deal with relate to funding, including some big projects that are multiyear and multidimensional, but ultimately revolve around funding. But we also have policy issues that pop up unexpectedly, and then we have to deal with that issue.

There was a proposal in the lame-duck session of the state legislature at the end of 2012 to change the rules on gun-carry permits. The proposal would allow people to carry concealed weapons in places that up to now have not been allowed, including churches, theaters, sports arenas, and on campuses.

As soon as the bill was introduced, we spent time talking with the bill’s sponsor, asking him, “What is it that you’re trying to accomplish by expanding the concealed-carry law?” We also talked to senior-level folks on campus to clarify what are our concerns were. Our biggest concern was that regardless of how responsible an individual person might be, we have a lot of eighteen-year-olds on campus and a lot of them drink. The mixing of eighteen-year-olds, alcohol, and firearms is not really a good idea. And even if the person with the permit is responsible, there could be a problem with their roommate or their friend getting access to their gun.

We had a serious concern about the potential for bad accidents to happen on campus if concealed weapons were allowed. We spent our time talking, both in person and on the phone, to the legislator who proposed the bill, to the legislative leadership, to the committee that was going to consider the bill, to opponents of the bill, and to our other colleague universities about what positions they were taking and whether there were other allies that we could work with.

Leech: At this point, are you just collecting information during these talks, or are you already arguing the university’s position?

Burnham: We’re doing both. We would start with an inquiry: “Why are you introducing it? What is your intention?” And we would follow with, “Here are our concerns.” We try to explain our institution’s particular perspective.

Leech: How do you come up with that perspective? Where does it come from?

Burnham: Usually it’s done in dialogue with senior-level folks on campus. In this case, it included our chief of police, the university president, other senior academic and administrative leadership, and the university’s lawyer, its general counsel. The general counsel was important because in the state of Michigan, the public universities are “constitutionally autonomous.” Of course, there’s always the question of what does that mean in practice?

Leech: Conceivably, the university could make up its own rules and govern itself?

Burnham: Yes. Actually, that was the tack we were able to successfully use. By meeting with the proponents of the bill and talking about the concerns we had, they agreed that they didn’t want to be advocating for people having guns in inappropriate circumstances. They were willing to accept putting language into the bill that acknowledged the university’s autonomy and that it would be within the authority of our Board of Trustees, who are publicly elected, to pass an ordinance to continue to keep concealed weapons off campus, out of our stadiums, out of our dorms, and our academic buildings.

In some of our conversations, we would make the point that the Department of Homeland Security, which does work with the university pretty regularly, is concerned about what we allow in our stadiums because our stadium holds more than seventy thousand people. The federal government is telling us not to allow purses in the stadium to prevent people bringing dangerous things inside, and now we’re going to allow concealed weapons in the stadium?

Between the fact that we are autonomous, the fact that legislators did agree that they’re not trying to mix guns and alcohol, and the potential for public safety issues in crowds like at football games, we made our point. So the legislators included the provision to allow us to make our own choice. Now, we supposedly already have that authority, and they were simply acknowledging it, but it was a greater acknowledgment of our autonomy than has been recently made. The bill passed in the state House and Senate, but then the tragedy at Sandy Hook occurred, and the governor, I think rightfully, vetoed the bill. But this will probably come up again in the future, although I don’t know how quickly they’ll be interested in taking it up.

What we as lobbyists actually do is talk. It’s a lot of sitting down with public officials, making the suggestions, and in some cases making written proposals or simply critiquing what they have written. It’s having dialogue with our allies and making sure that we talk among ourselves. It sometimes can include trying to get lots of alumni to call their legislators, but a lot of times, that’s not an effective approach, because if you’ve gotten to that tactic, you’ve probably already lost the fight.

Leech: That’s a tactic to use when you’re feeling like the underdog.

Burnham: Exactly. If a lobbyist is approaching advocacy the right way, it will include three things. There will be direct, face-to-face conversations that help legislators understand the university’s position and the university to understand the legislators’ position. There also will be discussions like that with university leadership, donors, and people who are important in their communities.

If you’re getting into a grassroots situation where you’re trying to mobilize alumni to call in, that can work, but efforts like those are a blunt instrument and need to be used judiciously. We want to move the ball, but we want to do it in a way so that we can still come back tomorrow and have another conversation with the policymakers, because tomorrow it’s going to be a different issue. We can’t use the blunt instrument of having two hundred thousand alumni jam the statehouse phone lines every week. We have to save that power for when we’re in a really tight situation and at a point where we have to go all in. No one can go all in on every item.

Leech: How does working on an issue that pops up, like concealed handguns, differ from what your office does day-to-day in terms of funding?

Burnham: The big difference is the time line. When an issue pops up—especially in a legislature like ours where the same party controls both houses and the governorship—things can move really fast, so you have to be incredibly nimble.

In contrast, the appropriations process has a cycle. There is a known pattern. The president/governor’s budget request is going to come out in the early part of February. Then there will be hearings, and the university will provide testimony. Lobbyists from our office will look at what was proposed by the Adminsitration and suggest changes at the level of the House and Senate subcommittees. You’ll have a point where the House will vote and the Senate will vote, and then they’ll go into conference committee. There’s a series of points in time when you have conversations with the same people and find that sometimes your allies on Day 1 are not your allies on Day 7 because they want something different, and on Day 14, you’re allies on a different part of the bill. So you have to be flexible and nimble, but there’s more of a steadiness to it.

It’s a lot more methodical and a lot more nuanced as you try to work your way through the appropriations process. You never are dealing with one single issue. Every appropriation bill will have multiple issues that affect the university, whether it be the base funding line, or the funding for a special project, or reporting requirements. In an appropriations bill, our office is always dealing with at least four or five different issues. We can’t push one too hard without putting some of the other issues at risk, so we have to be very careful in our approach. You have to balance the overall interests of the university. And often when the governor’s budget comes out, or the House acts, or the Senate acts, one or all of them may have introduced something new that our office wasn’t aware of before, that we then would have to decide whether to support or oppose.

At the end of the day, you’re trying to get the best overall outcome for the university, with the fewest oversight requirements, while at the same time getting as much money as you can. There’s always a midpoint and you’ve got to accept a certain amount of oversight for a certain amount of funding.

Leech: Now that you’ve explained these issues, could you walk me through an average day so that we can get a picture of how you would spend your day at the office?

Burnham: First, there’s no such thing as an average day. There are things that happen which are planned, like a visit by a legislator or a governor for a tour. Both Congress and the Statehouse tend to work Tuesday through Thursdays, so those are “session days” when our lobbyists are down at the Capitol a lot or on the phone with legislative staff. There might be a basketball game or a football game that I’ve invited people to come to. There might be an issue where some legislator’s constituent didn’t like their interaction with the university—for almost any reason. Our office has to try to figure out what happened and what, if any, resolution there can be, and try to make sure that it is resolved in the best way possible. There’s a lot of casework like that. Mostly, we spend our time trying to figure out what the legislature is likely to do next, and whether that will benefit or harm the institution. That requires a lot of rounds of communications between university officials and legislative officials with our office serving as translator and to some degree the train conductor.

Leech: Where do the local officials come in?

Burnham: For the local stuff, our office also has to deal with the traditional town/gown issues, where there are neighborhoods that don’t like the fact that university kids who live nearby are drunk and disorderly at two in the morning and leaving trash all over the street. The neighbors want to know what the university is going to do about it. We work hard with our communities to resolve those types of issues quickly and help both our neighbors and our students to understand and respect each other’s needs.

Our office also might get involved in local development plans involving property we own. Right now, we’re working with the city, and the county, and the local transit authority to get a new train station, a new track, and a new platform to upgrade our Amtrak station. There’s economic development at the local level. There’s “How do we work better with our community?” And new local officials are being elected every cycle, so our staff have to get to know them and their issues.

We work on all of those levels simultaneously. Today, I started the morning with a conversation with the governor’s office about the State of the State address. We have a major initiative we’re hoping to launch and we have leadership meetings that I need to schedule. So I needed to make sure that if I schedule those meetings, I wasn’t going to get surprised that the initiative didn’t get funded in the budget.

Then I met with a visitor from US Senator Debbie Stabenow’s office who came to campus to tour the site of our new Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

After that, I had a meeting with a newly elected councilwoman for the township that’s adjacent to the university. I had staff meetings, and this conversation with you, and then I have to brief our faculty and our graduate students on what’s going on at the federal funding level. I’m meeting with the budget group on campus to talk about the university budget. That’s just in one day. Tomorrow may be totally different.

Leech: When do you normally come in to the office and when do you normally call it a night?

Burnham: I have to say that one nice thing about working for a university is that I usually can get in around nine and I can usually go home between five and five-thirty. Except, of course, when I’m here on weekends or weeknights because we have important visitors to entertain.

When I go to Washington for the presidential inauguration, it may sound like a lot of fun, but actually, I’m going there to work. There are a whole bunch of folks I need to talk to, and I’ll have them all in one place. By and large, the quality of life is not bad, but there are some weeks when I don’t get free time even after hours.

Leech: That leads into my next question, which is about whether lobbying life is conducive to family life.

Burnham: Two points, Number one, I just finished a divorce, so there’s a reasonable question of how much my job might have something to do with that. That is probably so. Secondly, being a lobbyist for a public entity like mine is very different from being a lobbyist for a lobbying firm or a company where political action committee [PAC] fundraisers and campaign events take up most of your life. That’s one of the reasons why I enjoy working for universities. By and large, we don’t have any federal PACs and we have a very small state PAC, so I’m not spending my nights at campaign events. I will say that many of my colleagues who work in private-sector lobbying are spending four or five nights a week out until ten or eleven o’clock talking to people who are campaigning.

I personally question the value of that, because I have done PAC work before. The legislators and members of Congress just want more money. At the end of the day, you’re not really getting much influence. You’re just getting calls for more money. And especially if an organization isn’t a big campaign contributor, the only way it’s going to get attention is if it has reliable information. For a university like MSU, we aren’t going to get someone’s attention because of a campaign contribution; we have to be the source of good information on a whole number of subjects.

We also have to be telling them something that matters. Information is the only currency that really matters in Washington and here. Integrity is critical, because if officials find out that we’re not being truthful with them, they’re not meeting with us the next time. As much as the public perception may be that lobbyists are one step below lawyers—and sure, there are always some bad apples anywhere—most lobbyists know that if they don’t have integrity, they’re not getting very far for very long.

How does it all hit your family? A lot of that depends on your ability to balance work and home life. I’m very lucky in that with my job, I’m able to spend time with my kids—certainly more so than my other colleagues who work in the private sector. Lobbying, like a lot of jobs in Washington, is really a full-time, full-contact sport, and it can take up your entire life if you let it. I think quality of life for a university or a public sector lobbyist is a lot better. Of course, those jobs don’t pay quite as much, but that’s okay. I think it’s still worth it.

Leech: What is your favorite thing about your job?

Burnham: Engaging with students and working with them, and showing them what’s going on. It’s also a lot of fun getting to talk about a university doing research. I’m talking about the future, how things are changing, how things are getting better. I’m talking about being hopeful going forward. It’s a lot of fun because we are always looking at what’s on the horizon – and some of it is pretty amazing stuff.

Leech: What things do you like least about your job?

Burnham: Surprises. If I know what’s coming, I can pretty much deal with it. It’s the six a.m. text message that unexpectedly throws off my whole day. It’s the surprise turn that completely changes what our office needs to do for the course of the next legislative session. Those things happen and it’s hard. You can lay out a whole great plan, and then something that’s outside of your control happens and you have to deal with it.

Leech: You said you like talking to students. If one of them came to you and said, “Hey, I want to be a lobbyist when I grow up,” what would your advice to that person be?

Burnham: Learn to write and speak well. That is always a big challenge. Find a job on Capitol Hill, or on the state legislature, or on a campaign early on, because those are jobs that are hard to take once you already have a graduate degree, and life, and kids, and work, and all of that, because those jobs don’t pay very well. Most good lobbyists have spent some time working on the other side—working in the legislature, working for the administration, working on Capitol Hill—and they understand how the system operates and what the rules and procedures are, what the committees are, and why they are set up the way they are. Once you have some institutional knowledge, then you can go on to graduate school or law school if that’s what you choose to do.

Leech: A couple of people have mentioned to me the importance of writing well. Why is it important for lobbyists to write well?

Burnham: Lobbyists need to be able to prepare their presentations. They have to know how they’re going to say something. Lobbyists have to be able to condense their arguments to one page, because legislators and staff are just not going to read more than one page. Lobbyists have to be able to articulate what it is they want, why they want it, why it’s the right thing to do, why it’s in the best interest of the official they are talking to, and why it’s good for the state, the nation, or the institution. Lobbyists have to say all that succinctly and in a way that is compelling. That’s hard to do in one page and it runs completely contrary to how faculty members have been taught to organize their arguments.

Leech: What other qualities would you say are important or useful as a lobbyist?

Burnham: You have to be curious. You have to want to understand why things are the way they are, why things work the way they do. You want to always be learning. You’ve got to have the personal skills and the personality to be able to go up to a perfect stranger and start up a conversation. You have to be able to handle people yelling at you, usually for things you had nothing to do with, and not reply in kind.

Leech: Is the yelling coming from people within government or people outside of government?

Leech: [Laughs.] Is there anything else you’d like to say about your job?

Burnham: I think one of the biggest challenges for people who do this job is the public sentiment that somehow lobbying as an enterprise is inappropriate or tainted. I can appreciate in the world of post–Jack Abramoff why people would feel that way, but I would remind folks that anybody who speaks to power and seeks redress of grievances is doing what a lobbyist does. The only difference is that a lobbyist has decided to do that as a profession. Whether you’re talking about the Boy Scouts, or the Red Cross, or NOW [National Organization for Women], or any citizen organization of that size, they all employ lobbyists. There’s no interest that isn’t a special interest. They’re all special interests.

Leech: It’s only a special interest if you disagree with them. Otherwise, it’s an interest.

Burnham: That includes raising taxes, lowering taxes, pro-guns, anti-guns, balanced budget, against balanced budget—whatever. Those are all special interests. A lobbyist can speak on behalf of good things, and unfortunately, they also can speak on behalf of bad things, depending on who the client is. Both sides employ lobbyists. It’s like lawyers: it’s understandable why people would not like them unless they need one, but everybody likes their own lawyer. It’s a part of the process. If the lobbying is based entirely on relationships and not on substance, I can appreciate that is unsavory. Most good lobbyists are not like that.