Lyle Dennis

Partner

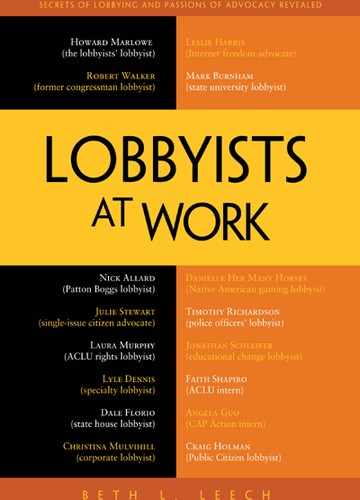

CRD Associates

Lyle Dennisis a partner in the lobbying firm of Cavarocchi-Ruscio-Dennis Associates, where he specializes in representing medical and scientific organizations and public and private universities. CRD Associates is relatively small and focused in the world of lobbying firms—it had billings of nearly $4 million in 2011, about one-tenth the amount of the largest firms. The firm does not have a political action committee (PAC), but its three partners individually gave more than $108,000 in campaign contributions in the 2012 election cycle.

Before coming to CRD Associates in 1994, Dennis directed the Washington office for the state of New Jersey. He came to Washington as chief of staff for Rep. Bernard Dwyer (D-NJ) after successfully managing Dwyer’s congressional campaign. Dennis earlier held several top staff positions within the New Jersey state Senate.

Dennis is a member of the steering committee of the Ad Hoc Group for Medical Research, the leading advocacy organization for the National Institutes of Health, and he is co-editor of Health Care Advocacy: A Guide for Busy Clinicians (Springer, 2011). He has bachelor’s degree in political science from Rutgers University and a master’s degree from the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers.

Beth Leech: I understand that your first job as a lobbyist was working for the state of New Jersey.

Lyle Dennis: That is correct. I was the director of the state of New Jersey’s Washington, DC, office. Most state governments have an office here in DC, most of them located just a few blocks from here in the Hall of the States.

Leech: Why do state governments need a lobbyist?

Dennis: The principal reason is because the interests of state government are not always the number-one thing on the minds of the congressional delegation from that state, and the interests of state government can be different than the interests of corporate constituents or individual constituents. There are very specific needs. For example, transportation aid is a huge issue for states. A congressional legislator from the state might not know exactly what the needs are in terms of construction or reconstruction of bridges throughout the entire state.

The member of Congress certainly knows what goes on in their district, but in terms of statewide issues, they may be less aware. For example, Medicaid is a joint federal-state program, and what happens at the federal level affects the state. A state’s interests might also be related to law enforcement grants or just about anything where the federal government interacts with the state. The state governments’ interests need to be represented to the delegation so that those members of Congress are aware of them going in to markups on legislation, negotiations, and conference committees—back in the days when there used to be conference committees and Congress used to pass legislation, which seems to happen so rarely these days.

When I represented the state of New Jersey, it was the last year of the Governor Jim Florio administration and the first year of the Clinton administration. But for twenty-six hundred votes, I would have had that job for five years instead of just one. At that point, directing the Washington office was considered a subcabinet position. It was essentially the same as being assistant commissioner, in terms of where it is on the hierarchy of state government.

Leech: Was the work primarily appropriations related, or were there other things as well?

Dennis: There are other, policy-related things as well. For example, there’s a program under Medicaid referred to as Disproportionate Share Hospitals. These are hospitals that treat an inordinately large percentage of indigent patients. Exactly how that’s defined can make a difference of tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars of federal aid going to the state. We would work on issues like that.

The other thing that a lobbyist does in that position is serve as the governor’s liaison to the administration, especially if the White House is of the same party and will talk to you, which was the case when I represented New Jersey. There’s a political component to the job as well. Governor Florio was a high priority for President Clinton because that governorship was one of only two that were up in the off-year election.

Leech: Coming into that job, had you ever thought you would be a lobbyist? Did you want to be a lobbyist when you were back in graduate school?

Dennis: No. When I was in graduate school, my intention was to work in the state legislature, which I did for four and a half years. I came to Washington when the then-majority leader of the state Senate, Barney Dwyer, got elected to Congress and asked me to come along as his chief of staff. I was twenty-seven.

I had been with him about eight years when I started thinking, “You know, what am I going to do next? This guy I work for isn’t getting any younger and neither am I. I have kids who are going to want to go to college. I started thinking that I would probably go into lobbying. I thought that I would probably be good at it or at least not bad at it.

Dwyer served twelve years before he retired. That was when I then went to work for New Jersey’s Washington office.

Leech: And after that, when Governor Florio lost the election, you came to Cavarocchi-Ruscio-Dennis Associates, which was then Cavarocchi-Ruscio.

Dennis: Yes. I was interviewing around town and I had a job offer from a competitor firm. This is going to sound like I’m very clever and manipulative, but I’m actually not this smart. I called the people who are now my two partners and said, “Hey, I got this job offer from so-and-so down the street. Here’s what he’s offering me. What do you think? Should I take it? Should I negotiate more?” Because I knew Cavarocchi and Ruscio. They used to come in and lobby me when I was Dwyer’s chief of staff. The response I got was, “We’ll call you back.” I thought that was an odd response.

The next day they called back and said, “Why don’t you come in and see us? We’ll beat that offer.” That was how I ended up here and then five years later, became a partner, causing the renaming of the firm to the totally unpronounceable Cavarocchi-Ruscio-Dennis Associates.

Leech: Thus CRD?

Dennis: That’s CRD in most people’s minds.

Leech: What sorts of clients does the firm tend to represent? And what sorts of clients do you tend to represent, if that’s different from the overall firm?

Dennis: I’m kind of a microcosm of the firm actually. We have forty-five or so clients. Earlier in their careers, my two partners were both appropriations subcommittee staffers for the Labor, Health, Human Services, and Education subcommittees—one of them on the House side, one on the Senate side. When the firm started, we had a very strong focus on appropriations issues, particularly in health and higher education. Over the years, we’ve expanded that fairly significantly, although it is still the majority of our client base.

For example, in the health area, we represent patient advocacy groups, physician organizations, and scientific research organizations, including the Society for Neuroscience, which is made up mostly of people with PhDs, and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, which is mostly MD researchers with a few PhDs mixed in. We represent several universities, including the State University System of Florida, which is eleven universities and six medical schools.

There are a variety of other things as well. We are big on running coalitions. For seven years, I ran a coalition to support the Human Genome Project.

Leech: What was important about the Human Genome Project, in terms of advocacy?

Dennis: The Human Genome Project was a scientific project at the National Institutes of Health [NIH] that sequenced the entire genome, all three billion chemical base pairs that are inside of every cell in your DNA, and the whole project took ten years. It was $3 billon over that period. Congress doesn’t appropriate multiyear, so it was an annual advocacy effort. What it ultimately led to is the stuff that you hear about all the time now on the news—that scientists have found the gene that causes a particular birth defect or scientists have now found the cause of a certain disease.

Leech: The coalition was there to help encourage funding?

Dennis: Yes, because there was also a private effort going on through a company called Celera. The difference between the public effort and the private effort was that all the public effort research was immediately put up online and was available freely to anyone within twenty-four hours of analysis. The private effort went into a for-profit company where the information was held internally. The societal benefit, of course, is to have the scientific information available for other researchers.

Leech: I hadn’t realized this at the time. Was the private company trying to prevent the public effort from going forward?

Dennis:There were some pretty fierce rivalries, and some of this is just individual personalities and some of it is the for-profit motive versus the not-for-profit motive. While the company was not overtly trying to undercut the public effort, there was enough discussion that some members of Congress began to say, “Well now, wait a minute. Why do we have to put up taxpayer money if a private company is going to do to this?” There was an educational effort needed to explain what the differences were and why the public effort was so important, and then it ultimately got done. The two groups finished sequencing the genome at virtually the same time.

Leech: Without the coalition, it’s very possible that the public side would not have succeeded.

Dennis: Yes. We once brought in three Nobel Prize winners to talk to key members of the Appropriations Committee to explain why this was so important. One of the Nobelists was James Watson of Watson & Crick fame, who discovered the structure of DNA. Three Nobel Prize winners and me—the guy who got a C in high school biology.

Leech: Each has their skills. What do you do when you’re running a coalition like this?

Dennis: What we did in this case was we talked to some pharmaceutical companies, not Celera, but others that were interested in having this information publicly available so they could use it in their research. We talked to some patient advocacy groups that also were interested in having this project go forward and not have to buy access to the basic research from a company, and we put the coalition together.

Leech: Does the impetus for the coalition come from you guys or does someone approach you and say, “Would you do this for us?”

Dennis: It originally came from a discussion with some folks within government, but they, of course, can’t lobby. Essentially what they said was, “Wouldn’t it be nice if somebody did this?” It was really nothing more substantial than that. I was very new at lobbying at that point. I’d only been doing this for about a year, so I had the time. Coalitions are very time-intensive. First of all, there is an inverse relationship between the amount of work people expect from you and the amount that they’re paying into the coalition.

Leech: The organization that’s given $100….

Dennis: Has a question a day. And the organization that’s giving $10,000, you never hear from. It’s just the way it is.

Leech: They figure you’ll handle it.

Dennis: What we try to do in this case was to balance the coalition with some industry folks, some big patient advocacy groups, things like the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and then some little mom-and-pop patient advocacy group for diseases that you’ve never heard of. Those small groups didn’t pay anything because they couldn’t. They were being run out of somebody’s kitchen. It took a year or two, but we ended up putting together about one hundred and twenty-five different members. Then we were up on the Hill, presenting language to Appropriations to support the project.

The coalition sponsored an annual lecture at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington. One year Al Gore spoke. He was vice president at the time, so it was a pretty big deal. We were operating at a pretty high level, drawing a lot of attention to the project, hoping to fund an effort that ultimately is going to lead to cures for a lot of diseases.

Leech: Is it very common for lobbying firms to initiate coalitions as an entrepreneurial thing, a way of saying, “Hey, there’s something you guys should be thinking about doing. We could represent you on that.”

Dennis: Absolutely. And there is also the “Hey, wouldn’t it be nice if we had a group that could do this because we can’t lobby.”

Leech: Is that coming from the legislative side or from the NIH side?

Dennis: It would be more NIH. There are groups that spring up around the institutes that are a combination of patient advocacy groups, physician groups, and sometimes corporate groups who are interested in the research that’s being done there. At NIH, there are Friends of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Friends of the National Institute on Aging, and Friends of the National Library of Medicine.

Those coalitions essentially are lobbying informally on behalf of a government agency to advocate for that agency’s budget. There also are coalitions like this informally affiliated with the Department of Health and Human Services [HHS]. For example, one of the agencies under HHS, the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality [AHRQ], does health services research and that sort of thing. One of the senior vice presidents here runs a coalition called the Friends of AHRQ.

Leech: You’re on the steering committee of another ad hoc committee, right?

Dennis: I’m on the steering committee on the Ad Hoc Group for Medical Research, which is a pro-NIH advocacy group.

Leech: In these sorts of groups, are you participating because your clients are on them and you’re representing them?

Dennis: For the most part, we’re doing it because they are great sources of information for our clients and for ourselves to be able to impart to our clients. In some cases, it is directly because the client has asked us to do it.

Leech: In some cases, you would be paid directly and, in other cases, it’s just good for business?

Dennis: It’s just good for business, exactly. The steering committee for the Ad Hoc Group for Medical Research meets every year with all of the institute directors at NIH, which then gives me relationships there. If one of my clients says, “Hey, there’s something going on in this institute where we’ve never been before,” I can say, “Well gee, I just met with the director three weeks ago. I’ll reach out there and see if we can’t get a meeting.”

There’s also a general educational aspect to the groups in terms of keeping track. As tight as budgets are in the government right now, NIH still spends more than $30 billion a year. That’s a lot of money. There’s a lot of opportunity that can be missed if an organization is not at the table. That’s what it’s about—being at the table.

Leech: I took you off on a long tangent, which was very interesting, but let’s back up because you were telling me about what your firm does.

Dennis: We also run something called the Coalition for Health Funding. There are seventy-five different organizations in the coalition and each of them pays dues to us to run it. It’s very active and the agenda is broader than just the NIH. The agenda is the entire public health service, so that would include the Centers for Disease Control, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Food and Drug Administration, and a lot of other health agencies. The coalition is looking at the bigger picture of funding for health. That has led to the creation of something called the NDD Coalition.

Dennis: The Non-Defense Discretionary Spending Coalition. Under the Budget Control Act that passed last year as part of the debt-limit deal, there’s a provision that says that if the Super Committee fails to make significant reductions in the deficit, there will be a process called sequestration that will take effect on January 2, 2013. That process will cut about eight percent from every discretionary program in the federal government—defense and nondefense.

The defense community—being wealthy, really well-organized, and all corporate—has started organizing to exempt defense from the sequestration. Because we’re running this coalition for health funding and health is a big part of the federal budget, we got together with the Coalition for Education Funding and some housing, transportation, and justice groups—basically everything that’s not defense—to create this NDD Coalition. We’re actually not making any money from the coalition, but we’re doing good work to ensure that defense and nondefense are all treated alike.

If you exempt defense from sequestration, you will double the cuts in nondefense spending. Now instead of losing eight percent of every program, nondefense programs would lose sixteen percent. That includes things like the FBI, the Immigration & Naturalization Service, border enforcement, and air traffic controllers. The cuts would occur a quarter of the way through the year, so they would effectively have a twenty percent cut through the rest of the fiscal year. So that is an important area to be involved.

I’ll give you a couple of other examples of what the firm does. I have a senior vice president who is a master’s-level genetic counselor. She worked in Francis Collins’ lab when he was the head of the National Human Genome Research Institute. She represents companies that are doing cutting-edge genomics research. These companies are in California, a lot of them are venture-capital funded, and most of them have “gen” somewhere in their name.

Leech: Why do companies like that need to be represented?

Dennis: There are a lot of policy issues at the FDA in terms of the companies getting approval for the tests or treatments they’re developing, and then there are payment issues with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]. It doesn’t do a company any good to get their new test approved by the FDA if CMS won’t pay for it. If CMS won’t pay for it, then private insurers won’t pay for it. The whole system gets tied together.

We help the companies navigate that system, which is very complex, with a million people involved. There are aspects of it that we don’t do because we’re not a law firm. The “gen” companies will have an FDA counsel for the legal side and then a firm like ours to help them navigate the political side, including when to go in to meet with the key people at the FDA or who to see at CMS.

Leech: Very good. How about you personally?

Dennis: Most of my clients are on the health side. What I personally work on are a couple of patient advocacy groups for genetic-based diseases and a couple of physician groups, one being the Society for General Internal Medicine and one being the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Leech: How did you end up with this expertise? You just told me you got a C in biology.

Dennis: Part of it is because the congressman I worked for was on the subcommittee that funded NIH and funded all of these health programs, so I already had been conversing with those agencies when I came to CRD. Then part of it is the experience of just doing it. Now, let me say this: you don’t want me touching your liver.

Dennis: That goes for everybody here. What we know is what we don’t know, and at what point should we pick up the phone and say, “Dr. So-and-So, I need you to talk to this congressional office because they have a question on viral hepatitis that would have me practicing medicine without a license.”

Do I know the difference between hepatitis B and hepatitis C? Yes, I do. Could I tell you with any great certainty whether your ALT scores should be 5.7 or 6.3? I have no idea. I don’t even remember what the initials ALT stand for, other than the fact that it’s something where the L is for liver. We go to the experts on that. Same thing in neuroscience: when we represent the Society for Neuroscience, we know when to stop and say, “Let us have someone get back to you with a definitive response on that.”

Often in policy, you don’t need to get into the real deep medical or scientific issues, but sometimes it happens. The Society for Neuroscience, a long-time client, asked us to work with a coalition that they wanted to develop called the American Brain Coalition. That coalition is comprised of the Society for Neuroscience, the American Academy of Neurology, and a bunch of patient advocacy groups for diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

One of the things we do for this group is provide staff work to the Congressional Neuroscience Caucus, which is an unofficial congressional caucus of members and their staffs who are interested in neuroscience issues. It’s now up to thirty or so members. We organize four briefings a year on Capitol Hill. We just did one a few weeks ago. It was about breakthroughs in neuroscience research. We brought in someone from Harvard and somebody from the University of California at San Diego. They were very prominent neuroscientists, who were able to talk in English as opposed to in neuroscience, and brief eighty Capitol Hill staffers on what’s the latest and greatest in neuroscience.

Some of what they said related to brain imaging and some related to new medications, but it was all targeted at educating Congress through their staff on what’s new in neuroscience, why it’s important, and how it ultimately is going to save healthcare dollars and all of that.

Leech: Why would the staffers want to know this?

Dennis:The staffers would want to know because their bosses will be called upon to vote on funding for NIH and on policy issues related to neuroscience—for example, stem cell research or animal research. Members of Congress are under enormous pressure from groups like PETA [People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals] to not support the use of animals in research. Hearing the other side of it is important to keeping that research going.

There’s always a reason why they need to know this. If there weren’t, they wouldn’t come to the briefing. The briefings have to be timely and pointed and they have to be an hour—maybe an hour and fifteen minutes. You can’t go any longer than that because you’ll lose them. It doesn’t hurt if you have a little food there, although even that has changed from when I was on the Hill, when it would be a dinner. Now there are limitations under the new ethics rules. You can’t buy a staffer dinner. It has to be hors d’oeuvres—food you eat with a toothpick.

We also are involved in a breakfast briefing next week. It’s for a patient advocacy group for the Congressional Baby Caucus—something you also didn’t know existed.

Leech: I did not.

Dennis: The group invited one of my clients to come in and testify about some newborn screening issues. We can get away with the small muffins and small bagels and that sort of thing, but we can’t do bacon and eggs. This is the brave new world.

Leech: It sounds like a lot of what you do is related to appropriations.

Dennis:A lot of it is, but it’s a decreasing percentage. If you’d asked me that question three or four years ago, I would have told you seventy percent. Now I would say it’s less than fifty percent. The reason for that is that appropriations bills used to be must-pass legislation. It used to be no matter what else, Congress would do its twelve appropriations bills, and therefore they were a place where other policy issues could get added in as well.

Increasingly, Congress has resorted to using continuing resolutions to fund the government and not actually passing appropriations bills. Or if they do, they pass these mega bills, where they lump a bunch of appropriations bills together into one bill. Because of that, it’s gotten harder for a lobbyist to get results in the appropriations process. We still do, but it’s harder.

We have shifted some of our lobbying work from Congress to the agencies, and within Congress, we do more policy work. The big thing on policy work for us was healthcare reform, which obviously was an enormous piece of legislation in which individual people up and down the hallway in our office might have been interested in a particular twelve-page section. Everyone says, “Oh, the bill is twenty-seven hundred pages. How could you possibly deal with that?” But we might be interested in twelve pages for this client, and one section for another client, and getting a sentence added for a third client.

Leech: Can you give me an example of one of those small things?

Dennis: Sure. It was not a small thing to the client.

Leech: Indeed, but small in terms of pages.

Dennis:We worked on getting some language in the healthcare reform bill to provide a bonus payment to primary care docs. Primary care doctors historically are underpaid relative to specialists and they’re underpaid for cognitive services. That is, they are underpaid for talking to a patient rather than for doing a medical procedure. If I have a basal cell carcinoma removed from my forehead, which takes three minutes, that dermatologist is going to get a lot more money than a primary care doctor who spends twenty minutes talking to an eighty-four-year-old patient with multiple illnesses, including diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and the beginnings of dementia. Dealing with that patient for twenty minutes will be paid less than the three minutes of scraping a little thing off somebody’s forehead.

What we were able to do, and it wasn’t just us alone, was to get a bonus payment built into the Medicare part of the healthcare reform law that essentially pays doctors an additional ten percent on those cognitive types of services. It’s not really enough. The problem we are trying to address is not, “Oh gee, these doctors make $180,000 and they ought to make $200,000.” The problem is that, “I’m a patient and I need a primary care doctor. I can’t find one because nobody’s going into primary care because the pay is too low.”

Leech: How do you go about changing language in a bill or getting something added in? When the general public thinks about lobbying, it’s often focused on the outcome of the bill: “Were you for it or against it?”

Dennis: For it or against it is way down the road. With these additions or changes to bill language, we would go a member of the committee or the subcommittee that’s writing the bill or writing that section of the bill. With healthcare reform, there were three committees in the House and two in the Senate that were involved. In this case, you would go to the Senate Finance and House Ways and Means committees. You would find a member who has a history of being supportive of primary care, and make your case to that member.

Leech: You go to speak to this person, and then if he or she agrees, is it done?

Dennis: No, but then the member of Congress essentially becomes the lobbyist on that issue. The member will go to the committee staff, which our office also meets with. The member also goes to the committee or subcommittee chairman or chairwoman and becomes an advocate for that provision. The member takes ownership of the issue.

Now, that’s a good thing and a bad thing. It’s a good thing in that ultimately only members of Congress can make these decisions and can do these things. The bad thing is once you turn it over to the member of Congress, you lose control of it. If somebody says, “Gee, why don’t you do it this way?” and “this way” is a stupid idea, or an anathema to the client, it’s very hard to turn it back around.

Leech: You’re trying to stay in touch during this period, I’m imagining.

Dennis: Exactly. We’re hopeful that we have a good enough relationship with the member or with the member’s staff that if somebody comes up and says, “Gee, you ought to do it this way,” that they’ll come back to us and say, “What do you think about this approach? Would that be better or worse, or how would your groups look at this? How would the primary care docs regard doing the payment in nickels rather than in dollar bills or electronically?” Whatever the idea is.

We try to stay as involved in the process as we can, but ultimately lobbyists aren’t really running the process. The staff has more influence than the lobbyists do, but ultimately the members really are the final bottom line. Now, having said that, are there things in bills that a staffer put there and no member really thought about it or paid attention to it—especially in a twenty-seven-hundred-page bill? Yes, of course, there are. But a lot of those are just routine wording changes, not major policy changes.

Leech: Why do you think members of Congress listen to you or to any lobbyist?

Dennis: There are a couple of reasons. First of all, I’m brilliant and charming.

Dennis: You can just erase that. There are a couple of reasons. First, you have to have a good argument. You have to have a case that matters. You have to have a case that fits in with their worldview.

You have to have something that doesn’t conflict with the values in their district. If a member of Congress is from New Jersey and has seventeen pharmaceutical companies based in their district, and you suggest, “Let’s do this to screw the pharmaceutical companies,” it’s going to be hard to get them to go along.

Leech: But what if the lobbyist is suggesting that the member of Congress should do something that supports the pharmaceutical industry? Why does a lobbyist need to say that? Why wouldn’t the member just do it?

Dennis: Because the member may not know about it. No member of Congress can know all of the nuances of every issue that affects their district or their state. It’s too much. There are too many variables. What the lobbyist is doing is providing information. Coming back to your question of why do they listen to you, let me answer it in the inverse: Why would they not listen to me?

If I provide them with bad information, if I provide them with heavily biased information, or if I provide them with information that doesn’t take into account their world view, their party, their district, I will quickly lose them as an ally.

Leech: And you don’t do that because you’re in it for the long term?

Dennis: Yes. If I wanted to slash and burn and work with somebody once, then I wouldn’t be able to go back to that person. They would say, “Geez, I did that thing for this guy and now I’m catching all this flack from this group or that group, and he never even told me they were against it.”

Leech: Your firm used to be pretty involved in earmarks—line items that brought money to particular projects or particular regions—before the House decided to ban them.

Leech: How was that different from the general appropriation process?

Dennis: First of all, I’m going to make the pro-earmark speech. The Constitution of the United States—you may be familiar with it—gives the power to legislate to Congress, not to a GS14 agency employee who lives in Vienna, Virginia, and commutes into DC every day. I have absolutely no problem with a member of Congress saying, “Of this $40 million going to rail projects, $1 million should be used to redo the Metuchen train station.” I don’t have any problem with that.

From a lobbying point of view, we never set out to become a big earmark firm, but because we did a lot of appropriations we ended up there. You have to understand that earmarks were very scarce, few and far between, until Newt Gingrich became Speaker of the House. Part of Gingrich’s philosophy, to help hold the majority and keep himself as Speaker, was to do earmarks out the wazoo because it’s stuff you can bring home and talk about to your constituents. Ironically, ultimately it was the Republicans who eliminated them and turned them into, “Oh, this is all the Democrats’ fault.”

Leech: And the lobbyists’ fault.

Dennis: And the lobbyists’ fault, and part of that was the Democrats’ fault because of various rascals. It’s what happens when the lobbyist is too closely tied to the member of Congress. When there are fifty campaign contributions from employees of company XYZ on Tuesday and then an earmark for $3 million added to a bill on Thursday, that’s bad stuff. The process got cleaned up after the Abramoff scandal. Unless a member was one hundred percent against earmarks, the member was portrayed politically as being for them. So that was the end of the earmarks, although as I said, we never set out to be an earmark firm.

Leech: Lots of universities were involved.

Dennis: Oh, tons of them. That was really Cassidy & Associates that began getting the earmarks for universities. By and large, they’re justifiable if it’s a good project. Our firm got the earmarks for the RUNet 2000 project, which wired the whole Rutgers University campus together and connected it to underprivileged high schools in New Brunswick, Newark, and Camden.

That was a good project. We got the university $10 million over a period of four years—a little over $10 million. They did good work with it. There were high school students in Newark who had completed all the math that was available to them in the Newark school system, and they could sit in their high school classroom and take a college-level math course.

Dennis: Yeah, it was a big deal and it was a good thing, but there was no competitive federal program to apply to for funding like that. The earmark ban completely wiped things like that out. In our case, we started seeing the writing on the wall. We started moving our clients into more policy-related issues and more broad appropriations issues. When earmarks went away, it barely made a dent in what we were doing because the clients were already doing other things. There are some firms in this town, and there are some individual lobbyists in this town whose business virtually got wiped out. Earmarks were all they did, and they were gone.

Leech: You mentioned campaign contributions. How important is that side of it to CRD?

Dennis: It’s not huge, thank goodness, because we don’t have a PAC. This is all out of our own individual pockets. It’s not a huge factor. I think it’s a factor. You’re not certainly buying anybody’s vote—certainly not at the level that we give. We’re not buying anyone’s vote any more than we’re buying anything from the staff person if we bought him or her a cup of coffee, which we’re no longer allowed to do.

Leech: I’ve looked at your filings with the Federal Election Commission, and the donations tend to be $500 here and $1000 there. Not across the board, by any means.

Dennis: Right, exactly. We tend to give to members of Congress who are helpful or who are supportive of our clients, but they are members who would probably be supportive regardless. I don’t think that Representative Frank Pallone of New Jersey is more supportive of Rutgers because we hold a breakfast for him, and I give him $1,000, and one of my partners gives him $1,000, and he knows we get twenty other people in the room who give him $500 each or whatever. He’s would be supportive of Rutgers regardless, because Rutgers is in his district.

Leech: So why do you do it?

Dennis: We do it because his people ask. We do it, I would say, just to deepen the relationship. It makes it easier to talk to him. It increases our recognition factor. I don’t have to introduce myself to members of Congress for whom I’ve raised money. This morning, I went to a fundraiser because another lobbyist asked me to do it. It was for a congresswoman who is very influential because she’s on the House Rules Committee, but I can’t remember ever bringing an issue to the House Rules Committee. I don’t need to know her better, but somebody asked me to do it. It was only $500, so I did it.

Leech: How often do you end up having to spend time either organizing or going to fundraisers like this?

Dennis: I just filed my semiannual report, and in the first half of the year, I made about nine contributions. That’s about normal. I do roughly twenty campaign contributions a year. They range from $125 to $1000. The $125 was for an event that I didn’t actually go to. I was trying to get somebody to stop bugging me, so I sent them $125.

My two partners probably do about the same. Our senior vice presidents tend to do a little less. Of course, they make less, and it all comes out of our own pockets.

Leech: I know at least some of your days—about twenty a year—are spent going to these fundraisers, but your average day, could you walk me through one of those?

Dennis: One of the things I like about what I do is that no two days are ever really alike, but there are certainly some generalizations I can give you. I usually am in the office by about seven fifteen a.m. I like that time between seven fifteen and nine o’clock because I can get organized, I can read all the newsletters, things like CQ [Congressional Quarterly] and those types of electronic newsletters that pop up onto our screens all the time. It’s funny with this stuff—it used to all be paper. Now it’s all electronic, although I do actually read the Washington Post on paper. I’m an old-fashioned sort of guy. That’s the early part of the day. Then once you get beyond that, I’ll have to give you a specific example, because it all diverges.

Yesterday, I was in here at seven fifteen. I had a staff meeting at nine o’clock with all the sixteen people who work here, except for the one that had a dentist appointment and the one who had to take his dog to the vet.

Leech: Okay, good. There’s some family time. That was my next question.

Dennis: I had a staff meeting. Then I had a phone call because I’m taking a client out to NIH later this week. I had a phone call from somebody from the National Cancer Institute who wanted to talk about that visit to NIH. Because we’re pitching a prospective new client later today, we had a planning meeting for that in the afternoon yesterday. In between that, I’m answering e-mails. I’m writing memos often requested in those e-mails, like, “Could you do a memo for me on such and such piece of legislation.”

Leech: The memo will be for a client or for someone in government?

Dennis: Either. For example, I did a memo yesterday for somebody on the Hill to use as the basis for a letter for their boss to send out to other members of Congress. The memo laid out the facts. When you take an issue to Congress, the more you can offer to do, the better the chance that they’re going to be helpful. Because the staff is so overworked and they’ve got so many issues and so much going on, the more things you can bring them as close to a finished product as possible so they can just do a cut-and-paste, the better the chance you have that they’re going to actually be helpful. That’s not any great secret. That’s just the way it works.

We had a planning session for the meeting with the potential client that we have later this afternoon. Then I was back to answering e-mails. I get about one hundred and fifty e-mails a day, which sounds like a lot, but some of them are read-and-delete. Some of them are very quick, some of them are more involved. In between, there are phone calls with clients, with the staff, all of that. That took me through to, say, six o’clock last night. I went home. I had some dinner. This is really interesting. I took out the trash, by the way.

Leech: Good. You were supposed to.

Dennis: Then I got back online and started answering more e-mails, the ones that had come in from the time I left here at six o’clock until I got back online at about eighty thirty last night. Now, don’t feel bad for me because I did have the All-Star game on TV and I have an office at home, so I’m very comfortable.

Leech: Is that usual for you to be checking, and working, and eating, and watching like that?

Dennis: Yeah. I work every night, usually an hour to two hours until my wife screams. Although increasingly she doesn’t scream anymore.

Leech: She’s used to it.

Dennis: Then just to take it one step further, today I went to a fundraiser in the morning. I had a conference call with a client, a patient advocacy group that wants to be supportive of an issue coming up before the FDA because the pharmaceutical company involved is making a drug that will help the advocacy group’s patients. We did that at eleven o’clock. I have this meeting with you. Then at three o’clock this afternoon, two senior vice presidents in the firm and I will be pitching a prospective new client.

We’ll do that meeting with the new client. Then one of my partners and I will do an annual review for one of our employees. That will end about five o’clock. I will answer e-mails, and return phone calls and whatever until six o’clock or so. I’ll go home. I’ll eat dinner. I’ll bring the garbage can in and I will get back online and watch the All-Star game while I’m answering e-mails.

Those are typical kind of days. Now, there are atypical things as well. Medical groups and physicians groups all have annual meetings and they are not located here.

Dennis: I wish. It’s not bad places. So far this year, I’ve been to Orlando, San Diego, Los Angeles, New York twice, Boston once, Chicago. Those are the ones that come immediately to mind, and those are virtually always on the weekends. What that means, of course, is that I’m working seven days a week during those weeks because I’m in the office Monday through Friday. Then Friday afternoon, I fly to Chicago, fly home Sunday night, and Monday go back to work. I’m probably away ten to twelve weekends a year.

Leech: What are you doing at those meetings? Are you presenting?

Dennis: It varies a little bit from group to group. For example, I mentioned the liver doctors before. When I go to their meeting, I do a presentation. Sometimes more than one, depending on how they have their agenda set up. I usually have one or two PowerPoint presentations, which means before I go, I’ve got to actually produce those presentations.

Leech: Are these meetings a place to get new clients, to make people more aware of what you do?

Dennis: Sometimes. But usually it’s more valuable in terms of retention of the existing client than it is in terms of recruiting new clients. The recent meeting in Chicago was for a group that we don’t represent, but it’s tangentially related to one that we do represent. I did have somebody come up to me after that meeting and say, “Hey, I want to talk to you about the possibility of doing some work with us.”

I was at a meeting in Boston last week, or two weekends ago, because of a patient advocacy group we work for, and a guy came up to me and said, “I’m from such and such a company and we are interested in this particular disease and would like to talk with you.” Now, in that case, I will listen to him but I probably won’t ultimately represent that company because there could be a conflict between the patient group and the company. We’re very careful about that.

Leech: Even down the line, such a conflict might develop.

Dennis: Right now, everybody may love each other, but if it turns out that the company wants to get the FDA to allow something and the patient advocacy group doesn’t think is safe, then we would have two clients in conflict. We go to great lengths to never get ourselves in that position because that is another thing that could destroy credibility in a hurry.

Leech: If the firm is hiring a new associate, what are you looking for?

Dennis: What we’re looking for is knowledge and experience. With very few exceptions, we don’t hire entry-level people. One of those exceptions is Tiffany at our front desk, who was an intern from Rutgers who we kept on to take over our front desk when somebody else retired and we moved our front desk person to become a vice president for administration. What we’re generally looking for in the folks who are doing the legislative work or agency-related work is Hill experience or relevant agency experience.

For example, we just hired somebody because we’re going to do more work in the defense area. We’re trying to go where the money is, and the guy we hired just retired after twenty-seven years in the Navy. He was also the Navy’s congressional liaison, so he knows virtually every member of the House or Senate who’s ever traveled on a Defense Department trip to visit some base somewhere. He knows the Pentagon, knows all the admirals, and knows people in defense firms.

Another of our lobbyists was a legislative director for a member of Congress who lost the election. She had worked in some areas that were really relevant to what we do. Most of the people here have worked on Capitol Hill. I was there twelve years. Other people were there shorter or longer times.

We have one guy who worked for a member of Congress from Philadelphia for fourteen years, the last seven as chief of staff. I’ve got another person who worked at GAO [Government Accountability Office] for about five years and then was lobbying for an association. She was running a coalition and I went to the coalition meeting and saw her in a meeting with congressional staff. She was so good that I came back here and said to my partners, “I just met our next vice president.” We hired her, and she’s been fantastic.

We look for people who have relevant experience, good smarts, want to work, and have a little bit of that entrepreneurial spirit. Because essentially what we are doing every time we meet with a client is a job interview. We’re selling all the time. When we pitch a prospective client, we’re saying, “Hire me. I’m the best one for this job.”

In the meeting this afternoon with the prospective client, I will go in and do five minutes on the background of the firm, how big we are, how long we’ve been around, and about our philosophy. Two of our lobbyists will talk about the substance of what’s going on in higher education and in defense, and how we see those communities intersecting. Hopefully, I won’t have to say another word.

Leech: What advice would you have for someone who thinks they want to be a lobbyist?

Dennis: The first thing is to get some experience, even though the Hill is enough to drive you nuts. It’s not mandatory, but it’s really helpful to have an inside understanding of how decisions get made on Capitol Hill, not just what you learn in your political science classes because it doesn’t work that way over here anymore.

If you’re inside it and you get to know the people, and you’ve got the TV with C-SPAN on all the time in the office, and you’re meeting people from other offices, and you’re involved in issues, and you’re reading legislation and trying to figure out what makes sense and where your boss’ positions have been, then all of that is a good foundation for working the system from the outside.

It’s very different from the outside. Information is harder to come by. People who returned your calls for years won’t return your calls or don’t return them as quickly. You’re struggling sometimes to put together the real story: “Why did they change their position on this? Why did they vote that way?” I think working hard inside Congress or inside an agency is very valuable, and easier than trying to learn it from the outside.

Leech: Even after the revolving-door glow disappears, that time inside is still helpful?

Dennis: Yeah. The concept of the revolving door is interesting. My experience is that it often only revolves one way. I was on the Hill for twelve years, then I left and never went back. I know some people who have done literal revolving: on the Hill as legislative director, out for a couple of years to lobby, then back on the Hill as chief of staff or committee staff director, out again to lobby some more. There are people who do that. It does raise eyebrows because it raises the question, “Are you trading on your inside information?”

It is, however, harder to trade on information now with the one-year or two-year lobbying bans for former government officials. A lot changes in a year. The turnover on Capitol Hill is twenty percent a year. By the second year out, two-fifths of the people are different.

Leech: Do you think the career of being a lobbyist is conducive to having a family?

Dennis: I have a wife, two grown kids who are both married, and two grandchildren, with a third one on the way. It can be difficult. But I’m in maybe a better position than some because I’m a partner and no one is going to say, “Why are you leaving?” or “Why weren’t you in on Friday?” I just spent the middle of last week, the Fourth of July holiday, at the beach with my son, daughter-in-law, and grandson who is three months old.

Then on Thursday of that week, I drove to my daughter’s house in New Jersey. I was basically out of here all of last week. But Congress was in recess and it was a holiday week. I probably was only getting seventy-five or eighty e-mails a day last week, because it slows up.

Leech: Because everyone was on vacation?

Dennis: Exactly. You can have a life. I went to Aruba for a week in April. I went to the beach Memorial Day week for the entire week, with both sets of kids and grandkids. You can do it. You have to manage your time well. If I’m going to take a vacation, the two weeks leading up to it are a pain because basically I have to anticipate what’s coming up that week I’m going to be away and how much of it can I get done.

The other thing that we do here—and I think a lot of firms do this—is to run it kind of like a medical practice. Everything is a team-based approach. If I’m gone, liver doctors can call Erika and they know that she works with me. If she doesn’t know the answer to whatever they’re asking because it’s something I’ve been working on, she can get the answer. My partners and I cover for each other, so it’s manageable. You can have a life and do this, but you also can let it consume you. There’s always something else you could be doing, and sometimes you have to just say, “Okay, the world is not going to end if I miss that meeting on Tuesday night at eight o’clock. I need to go home.”