Introduction

In the popular view, the word “lobbyist” is often taken to be synonymous with “special interest” and “corruption.” Media stories assume that lobbyists twist arms and force government officials to do things that they otherwise would not. Campaign contributions are equated with bribery.

Professors who study the topic, however, have learned that lobbyists are more likely to spend time with government officials who already share their views. Dozens of studies have discovered that, on average, organizations that give more campaign contributions succeed in their policy goals no more often than we would expect by mere chance. And only about a third of the thousands of interest groups active in Washington even have a political action committee with which to give campaign contributions. The other two-thirds of the interests give zero dollars to candidates.

Why, then, are there so many interest groups and so many lobbyists? There are more than 12,000 registered lobbyists in the nation’s capital, but the legal definition of a lobbyist is narrow, and so that number vastly undercounts the number of people who do policy advocacy as part of their daily jobs. During a single year—2011—interest groups in the United States reported spending $3.33 billion on lobbying and advocacy efforts not related to campaign donations.

One reason for the large numbers is that lobbying is part of a political arms race. Research that four of my political science colleagues and I have conducted showed that moneyed interests did win more often when there was an extreme imbalance of resources between the two sides of an issue.1 It was just that such an imbalance didn’t happen very often—only in about 10 percent of the cases.

Another reason for the large numbers of lobbyists is that government today is involved in so many things. In Chapter 8, for example, Christina Mulvihill, an in-house lobbyist for Sony, talks about how many different federal agencies regulate a television set. And mostly the numbers are so big because, even without twisting arms, sometimes the alliances that lobbyists have built, the arguments they have made, the information they have collected, or the stories they have told can indeed make a difference in the policies that affect our lives.

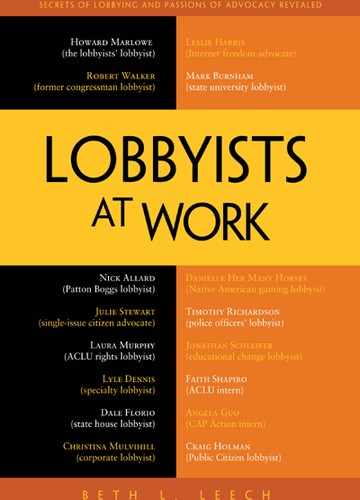

In selecting the sixteen political advocates profiled on these pages, I have tried to provide a broad overview of the profession. Perhaps the most important distinction is between in-house lobbyists, who work directly for a company or nonprofit, and contract lobbyists (so-called “hired guns”) who work for one of Washington’s many lobbying firms. Five of those interviewed are the founders of or partners in a lobbying firm. In the first chapter, Howard Marlowe is president of his own lobbying firm specializing in representing local governments in Washington. In Chapter 2, Robert Walker is a former member of the US House of Representatives with a fascination with aerospace who for more than fifteen years has been a partner in a prominent Washington lobbying firm that bears his name. In Chapter 3, Nicholas Allard, a partner in the world’s largest lobbying firm, Patton Boggs, is a lawyer who has spent time in and out of government and who today is the dean of Brooklyn Law School. In Chapter 6, the career of Lyle Dennis begins in state government, transitions to Washington, and eventually into the lobbying firm where he now is a partner. In Chapter 7 we hear the story of Dale Florio, who founded what is now the largest state-level lobbying firm in the country.

In-house lobbyists in Washington may work for a company—like Christina Mulvihill in Chapter 8—or they may work for a trade association—like Danielle Her Many Horses in Chapter 11. Her Many Horses represents Native American tribes involved with casino gambling, but there is an enormous range of trade associations in Washington representing virtually every category of industry or business, from cell phones to frozen pizza to medical device manufacturers. Other lobbyists work for professional associations and unions. Doctors have the American Medical Association, political scientists have the American Political Science Association, and lobbyists themselves have the American League of Lobbyists, a professional organization that Howard Marlowe discusses in Chapter 1. In Chapter 12, Timothy Richards of the Fraternal Order of Police talks about the role of his organization, which can act as a union at the local level but in Washington takes on the role of professional organization as it advocates for policies to help law enforcement.

Many governmental entities, including a majority of the states, have their own lobbyists in Washington. Lyle Dennis (Chapter 6) spent a year of his career lobbying for the State of New Jersey. Large institutions like hospitals, museums, and universities also often have their own in-house lobbyists. Mark Burnham in Chapter 10 describes what it is like to lobby for a large research university, Michigan State, given the importance of federal research dollars and federal aid to students.

Six of the chapters deal with the world of nonprofit citizen advocacy. These advocates sometimes fit the legal definition of lobbyist—like Laura Murphy of the American Civil Liberties Union (Chapter 5) or Craig Holman of Public Citizen (Chapter 15). In other cases, the interviews are with policy advocates who are not required to register as lobbyists because they spend relatively little time directly contacting members of government and more time providing information to their members, the media, and the public. Leslie Harris in Chapter 9 and Jonathan Schleifer in Chapter 13 have been registered lobbyists in the past, but today have shifted roles. Harris runs a nonprofit organization devoted to Internet freedom. Schleifer directs a nonprofit organization in New York that advocates on education policy. In Chapter 4, Julie Stewart has never been a registered lobbyist, but the nonprofit she founded works ceaselessly to get media, congressional, and legislative attention directed at the problem of unfair prison sentences. Chapter 14 features a discussion with two Washington interns—Angela Guo and Faith Shapiro—as they talk about what it is like starting out in the world of advocacy.

As a career, political advocacy has been a growing field because of the expansion of government. The Washington, DC, economy emerged relatively unscathed from the economic downturn of recent years. But as the career paths of most of the political advocates in this book show, it is relatively unusual for someone to go directly into lobbying as a profession. Most begin with at least a few years working in entry-level positions within government or nonprofits, and some spent many years rising through the ranks before transitioning into lobbying. As many of the chapters advise, would-be lobbyists should follow their passion and do what most interests and motivates them, be that law or policy in general or some specific topic like civil liberties or education. The career path to advocacy extends from the experiences and knowledge built in those early years.

About half of the interviews for this book were conducted by phone and the other half in person, in the lobbyists’ own offices. My goal was to interrupt with questions as infrequently as possible, to get each person talking, telling his or her own story in his or her own words. Many of the central questions are the same throughout: How did you become a lobbyist? Tell me about a recent issue that you worked on. Describe an “average” day. What advice can you offer to those who are interested in lobbying as a career? But in all of the interviews I tried, above all, to just let the conversation flow. The interviews provide insight into what motivates these advocates and what made them want to enter a career that has such a negative connotation in the public view. Why did they want to be lobbyists? And now that they are lobbyists, what are the rewards that they find in following their policy passions?

1 Frank R. Baumgartner, Jeffrey M. Berry, Marie Hojnacki, David C. Kimball, and Beth L. Leech, Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why (University of Chicago Press, 2009).