Chapter Nine

Don’t Recruit a Star; Create a Constellation

For centuries we have understood that a galaxy is a massive, gravitationally bound system consisting of individual stars that naturally attract one another. Scientifically we understand the naturally occurring phenomenon of gravity and the role it plays in keeping celestial stars in orbit with one another, but we haven’t used this knowledge to understand how human stars can create their own gravity with one another to create a professional galaxy of top performers.

A galaxy starts with individual stars, just as exceptional organizations and sports teams start with the success of key individuals. Pele, David Beckham, Magic Johnson—just to name a few—carried a disproportionate share of the credit and responsibility for their teams’ successes. Steve Jobs put Apple on the map and created a company that has both survived his demise and thrived in his absence. Like their celestial counterparts, these supernovae consistently caused a burst of energy that outshone the entire team—their respective galaxies. Unlike their celestial counterparts, these luminaries did not fade from view almost immediately. Instead, they led their teams to athletic or corporate victory over an extended period of time.

When you recruit a star, you’ve taken an important first step in building a galaxy—but only a first step. If you stop there, you won’t enjoy much more success than if you’d saved the money and hired ordinary people in the first place. Similarly, if you recruit a collection of stars and fail to help them develop some degree of cohesion, you doom yourself to the track record of leaders who thought assembling some top performers would suffice. Just as a world-class orchestra needs sections of string, brass, woodwind, and percussion instruments, and a conductor who can help them make beautiful music together, organizations need exceptional, diverse talent in key positions that their leader can orchestrate to create something bigger and better. Top performers don’t make this easy, however.

Research offers overwhelming evidence that groups of extremely bright and talented individuals often appreciably underperform when compared to groups comprised of average or above-average talent. Too often, leaders think they’ve done their jobs by collecting the individual stars. Then they and everyone else retreat to a safe distance to watch the innovative fireworks. Frequently, however, instead of engendering “oohs and ahhs,” the group—which never formed into a team—causes a hugely expensive dud.

Measuring Team Members

In my work with executive teams, I have noticed the links between input (the team members) and output (the team’s decisions, actions, and results). Only those teams that start with exceptional people can expect extraordinary results. Seldom have I found ordinary people uniting to create something great—even though these kinds of teams can often build synergy and fashion something that surpasses the sum of their collective talents.

Usually before I work with an executive team collectively, I have assessed each member individually, using a battery of tests that measure decision-making, problem-solving, knowledge of leadership, and relevant personality characteristics. Often I have also engaged in a 360 interview process to identify behaviors that help or hinder top performance, and I have examined performance reviews. The aggregate of these data gives me a clear picture of the individuals on the team and forms the foundation for the strategy or change management work that lies ahead.

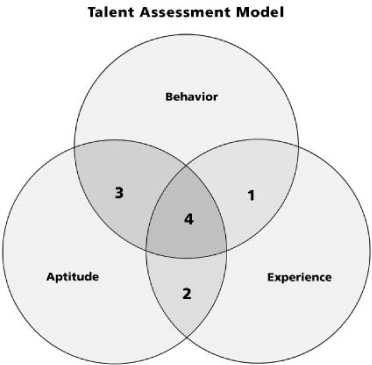

Drawing from my general framework of looking at people from a variety of perspectives, leaders can use the following model to assess the individuals they want to assign to a team.

1. Behavior + Experience

People that you consider a One would not make good virtuoso team members because they lack the aptitude to keep up with the others. Unless they offer a specialized skill related to their experience, don’t consider them candidates.

2. Experience + Aptitude

You’ll often find situations when you’ll want to include Twos on a team because they have the intellectual firepower and experience to figure out what has to happen. They will excel at decision-making, but because they don’t have the requisite behaviors, they may fail to influence others. Or, they may consciously or unconsciously sabotage the best thinking and efforts of their teammates. Depending on the problem behaviors that stand in their way, the leader can often coach these individuals to success.

3. Aptitude + Behavior

People that you would consider Threes often make excellent virtuoso team members because other members of the team can compensate for the experience that an individual person doesn’t have. Collectively, therefore, they can shore up the team’s efforts.

4. Behavior + Experience + Aptitude

Fours are the ideal candidates for team membership—and everything else. When you put a team of them together, you can expect amazing results. But you can also expect incredible problems—especially if you assume that they’ll automatically gel with a collection of other Fours. They won’t. They will need your help and insight to guide them through the predictable and inevitable turbulent waters of virtuoso team membership. Anticipating both the problems and opportunities associated with the formation of a virtuoso team starts with an understanding of eight factors.

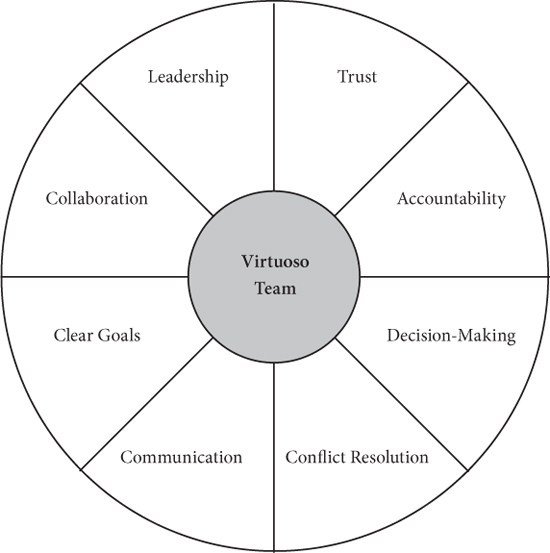

The Eight Functions of Virtuoso Teams

Building a team of exceptional people involves appreciating how individual members’ characteristics and personalities unite to form the unique culture of a virtuoso team. Satisfaction, performance, productivity, effectiveness, and turnover depend, to a large degree, on the socio-emotional makeup of the team. But one thing remains constant. Stars commonly think they lose their ability to shine when in a galaxy—their distinctive quality diminishing as others shine beside them. Consistently teams underperform, despite all the extra resources—problems with coordination, motivation, and fear of losing control chipping away at the benefits of collaboration.

Leaders who aspire to assemble a team of top performers will face daunting obstacles if they don’t structure and build the team at the onset. Without structure, a team of stars will flounder unproductively, often concluding that the team’s efforts are a waste of time. Pessimism will pervade. Conversely, when leaders define expectations, impose constraints, and help members clarify norms, roles, and responsibilities, the team can spend its time carrying out the task.

Leaders find themselves most motivated to spend time involved with the team when it faces a roadblock, but often that will be too late. A more proactive approach would be to do the building of the team when it’s actually forming or when things are going well. The following eight functions will help you with this structuring and position you to create a galaxy of stars, not a collection of egos:

No two teams, not even two teams of stars, will look alike. However, when they understand the universal dynamics that contribute to successful interactions among exceptional people, leaders can adapt and adjust their communication to the situation and make choices that will benefit the team and the organization. It all starts with trust.

Trust

As I mentioned in Chapter Eight, trust has four main constructs: integrity, competence, predictability, and the belief that you are cared about. In order for star performers to trust their leaders, they must satisfy all four aspects of trust. Star performers who form teams carry these same expectations into the team setting and apply them to their team members, but things become more complicated with more moving parts.

People realize they’re vulnerable to their bosses by dint of the boss/employee relationship. They accept this structure. But allowing themselves to become vulnerable to peers in a team situation introduces another level of complexity. Using the four constructs, then, each member must “trust” each other member to act with integrity. In a team situation, members often describe the nuances of integrity when they report that they find a member credible—that they can not only feel confident about the content of comments but also have faith that the member offered them in a spirit of mutual respect.

The leader will see evidence of trust among team members when they begin to admit mistakes to one another, and to offer and accept apologies. They do this only when they feel comfortable enough that neither the boss nor any other team member will use the information in any harmful way. The immediate and long-term payoff is that candor will remain high, whether the news is good or bad. Similarly, members will give each other dispassionate, accurate feedback about both ideas (content) and behaviors (process). Don’t count on balanced feedback, however. Stars tend not to compliment themselves or others nearly enough. They spot flaws and report inconsistencies; they don’t usually praise.

When trust builds during a period of time, members start to believe that teammates will behave in predictable ways, even when those ways aren’t necessarily positive. For example, one member, perhaps the lead finance person, might seem fixated on the fiscal implications of every decision, whereas the compliance officer can’t discuss options that threaten regulatory restrictions. Fair enough. Those members have the fiduciary responsibility to oversee a part of the organization, so their concerns will carry over to their team roles. Others can predict that they will raise the red flags in discussion, even when they seem to act as business prevention units.

The willingness to be vulnerable—to link one’s own success to another’s—starts with the fundamental belief that you are cared about. Not necessarily that you are protected or nurtured, but that you won’t be sacrificed on the corporate altar if things go awry. Stars repeat an internal mantra: “If I sink or swim as a result of your efforts, you’d better be a good swimmer yourself and someone who will throw me a lifeline if I need it.” When that caliber and quantity of trust pervade the team’s interactions, productivity will follow.

Accountability

When members literally don’t understand what their teammates expect of them, how can they reach their potential and avoid the pitfalls along the way? Problems surface when members haven’t established clear lines of responsibility. They don’t communicate, they haven’t clarified publicly what each person needs to do—tasks to be completed and decisions to be made, and members haven’t discussed openly their expectations about appropriate behavior. Ambiguity reigns and establishes itself as the enemy of accountability, which compromises commitment. This lack of understanding creates barriers among team members that significantly impede efficient and effective teamwork.

The world of aviation gives us grist for this particular mill. During the Cold War, the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC), the major command that would have dropped nuclear bombs, had that become necessary, determined that teams performed better as “hard crews.” These men trained together as a crew, flew as a crew, and were evaluated as a crew. The men knew what to expect of one another; trust remained high; and performance improved.

The commander of SAC then transferred to the Material Airlift Command (MAC) and imposed hard crew protocols on the pilots in that command. In addition to encountering significant resistance, few found the approach effective. MAC prided itself in standardization. In other words, no matter what pilot or co-pilot sat in the seat, others could expect him to perform in a standard, orthodox way. Leaders didn’t attempt to identify star aviators; they wanted predictability, precision, and safety.

The airlines operate on a model closer to that of MAC. Crews change regularly, sometimes several times in the same day. Once again, no one attempts to distinguish one pilot from another in terms of performance and skill. The FAA, the airlines, and the passengers agree on one thing: they all want safety.

In any of these crews, accountability is key. As the pilots go through the checklist, they listen for pre-ordained phrases and standardized responses. For instance, when they hear “Down the gear” instead of “Gear down,” the standard command, more often than not, the listener will hear “Say again.” The accountabilities on these crews are so well-honed and practiced that the pilots train themselves to hear what they expect to hear. When they don’t, progress stalls.

Leaders who aspire to build a team of stars can learn lessons from all these groups but should not infer universal best practices that will transfer to exceptional business teams. In SAC, decision-makers saw the value of familiarity and linked it to accountability. In the other Air Force commands and in the airlines, leaders seek standardized practices and procedures and don’t want creative deviations from the norm. You’ll want accountability and minimum competency levels, but you’re going to need more.

In your world, you want reliability coupled with entrepreneurial thinking and creativity that goes beyond minimum competence. You want the value that comes from standardization without the regimentation. You need a degree of safety and predictability but also the ability to agilely out-maneuver your competition. You want your stars to take calculated risks but not reckless ones. It’s a tricky balance, but teams achieve it when they continuously clarify objectives, roles, and decision-making authority.

Having candid discussions about areas of accountability and each of the aforementioned issues can help the team overcome the discord so members can get back on track. When I work with executive teams, I encourage them to use an accountability charting format similar to the traditional RACI approach—responsible, accountable, consulted, informed. (See the Appendix.)

Accountability charting helps team members operate more effectively by clarifying each team member’s responsibilities and expectations. Charting helps everyone understand who should participate in which decisions and identifies the right people for work assignments, projects, meetings, and task forces. It also helps people learn how not to step on each other’s toes and how not to assume someone else will take care of a particular task.

As the leader, once you have created a culture of accountability and commitment, your role changes. At that point, you should leave the policing of behavior to the team. Peer pressure goes a long way on virtuoso teams. Each individual realizes he or she is playing in the big league and doesn’t want to disappoint the other players. This fear alone will cause people to behave in functional ways—or it won’t. Either way, the team will need to work things out. Usually tolerance of sub-standard performance or violation of team norms vanishes on this kind of team. You may be called upon to act as the external arbiter, but when you do meet to discuss issues, reward and punish the team as a whole—not as individuals. And keep the spotlight on the decisions the team makes, not just on tasks accomplished.

Decision-Making

Conventional approaches to understanding teams usually address the work the team performs—the tasks they accomplish by functioning collectively rather than individually. When you create a galaxy of stars, however, the emphasis shifts. You assemble stars when you need bold decisions and stellar analytical reasoning—not all hands on deck.

In Landing in the Executive Chair, I used the team aboard Apollo 13 to demonstrate how exceptional people working together can achieve unprecedented success, even during a time of crisis. We recall that on April 11, 1970, James Lovell commanded the third Apollo mission that was intended to land on the moon. Apollo 13 launched successfully, but the crew had to abort the moon landing after an oxygen tank ruptured, severely damaging the spacecraft’s electrical system. Despite great hardship caused by limited power, loss of cabin heat, shortage of water, illness, and the critical need to reengineer the carbon dioxide removal system, the crew returned safely to Earth on April 17. Even though the crew did not accomplish its mission of landing on the moon, the operation was termed a “successful failure” because the astronauts returned safely. It also remains a case study in exceptional teamwork.

Author and researcher Meredith Belbin began using the term “Apollo Syndrome” for a different reason. After assembling teams of people who had sharp, analytical minds and high mental ability, he discovered that they don’t always or even usually achieve the success that Lovell and his crew enjoyed. In fact, Belbin discovered that when these kinds of teams developed a “failure is not an option” mentality, often they committed collusion in their own failure.

The failures seemed to be due to certain flaws in the way the team operated. That is, they attempted to function as a team of average or above-average performers, yet they were stars. They spent excessive time in abortive or destructive debate, trying to persuade other team members to adopt their own views, demonstrating a flair for spotting weaknesses in others’ arguments. This led to the equivalent of the “deadly embrace.”

In computer terms, “deadly embrace” signifies a problem when two computer programs vie for control, a phenomenon that occurs when each program waits and prevents the other from making progress. A similar situation can occur in team discussions when people try to influence others to concede the flaws in their arguments, without conceding the flaws in their own. Instead of looking for points of agreement, everyone stays rooted in the orientation and value of spotting inconsistencies.1

My own research of virtuoso teams reflects Belbin’s findings. If leaders don’t recognize and embrace the differences between virtuoso teams and ordinary teams, these problems become likely:

• Team members tend to make decisions that reflect their own best interest.

• Members spend more time debating than analyzing, so they waste time.

• When you assemble a group of dominant thinkers who have grown accustomed to being right, members abandon the give-and-take required for effective solutions.

• Members spot problems early, oppose and propose, and the group abandons viable solutions too early. Brainstorming ceases.

• When rivalry sets in, members lose focus.

Only a strong leader can shepherd the talents, skills, and egos of star performers to help them realize their greatest accomplishments through collaboration. Athletic coaches do it every day, but other leaders haven’t been quite so successful. Abraham Lincoln provides the exception to the rule.

On May 18, 1860, William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Edward Bates, all rivals for the presidential nomination, waited to hear the results from the Republican National Convention. When Lincoln emerged the victor, his opponents felt dismayed and angry, but Lincoln himself put the former contention aside. Displaying his signature statesmanship, Lincoln knew he had to assemble a cabinet that represented the best talent available, regardless of previous differences. Lincoln also included Montgomery Blair, Gideon Welles, and Norman Judd, all former Democrats, and William Dayton, a former Whig. Lincoln could have made more predictable choices in establishing his cabinet, but he didn’t. Instead, realizing the challenges ahead for healing a warring nation, he created his galaxy of stars—one characterized by diversity of thought and ideology.

Lincoln understood his rivals and respected them, even when he disagreed with their ideas. Those feelings led him to bring his disgruntled opponents together to create the most unusual cabinet in history. By marshalling the talents of these men, Lincoln preserved the Union and won the war. But each day brought new conflicts and decisions.

The cabinet consisted of strong men—all stars in their own right—but Lincoln taught us something else. Because this prairie lawyer from Illinois understood that extraordinary times demanded that he abandon ordinary solutions, through courage and prescience Lincoln guided his team of rivals to make unprecedented decisions that would shape the nation and the world. Here’s what he did:

• Lincoln faced reality. He never lost sight, and didn’t allow others to lose sight, of the complex task he faced in building a cabinet that would preserve the integrity of the Republican Party in the North while providing the fairest possible representation from the South.

• He put a premium on collaboration, but he didn’t hesitate to encourage confrontation to achieve it. The members of his cabinet clashed violently and continuously, but together they emerged victorious.

• Lincoln led with logic and didn’t let his personal feelings for these men or his past experiences during the campaign cloud his judgment. Instead, he sought and obtained the best thinking available.2

Few leaders invite conflict, even when it can result in the best outcome, but not many of us would consider anything about Lincoln or the times in which he led our country typical or representative. Lincoln put aside his own emotions and required his team to do the same. They may not have liked each other, and certainly they didn’t share common opinions, but together they shaped history.

Conflict Resolution

As Lincoln’s team of rivals taught us, not all virtuoso teams form seamlessly or easily. Some have to navigate turbulent, unrelenting waters before they reach shore. But the steering of the vessel remains paramount to success in all scenarios, as it did with Lincoln’s team—and the team that discovered insulin.

Before the discovery of insulin, diabetes led to death. Doctors knew that sugar worsened the condition of diabetic patients and that the most effective treatment demanded putting the patients on very strict diets with sugar intake, and food in general, kept to a minimum. Doctors and researchers developed the mantra: “The less food, the more life.” At best, this treatment caused patients to live a few extra years, but it never saved them. In some cases, the harsh diets even caused patients to die of starvation.

Dr. Frederick Banting, a Canadian physician, developed a deep interest in diabetes after reading an article in a medical paper on the pancreas. The work of other scientists had indicated that the lack of a protein hormone secreted in the pancreas, which they named insulin, caused diabetes.

Determined to investigate the possibility of extracting insulin from the pancreas, Banting discussed possibilities with various people, including Professor John Macleod at the University of Toronto, a leading figure in the study of diabetes in Canada. Macleod didn’t think much of Banting’s theories, but Banting managed to convince him that his idea merited further research. In 1921, Macleod gave Banting a laboratory with a minimum of equipment, 10 dogs, and a research assistant named Charles Best.

Hardly the gleaming vision that he had imagined, Banting found the lab shrouded in veils of dust and cobwebs, resembling the lab in a Frankenstein movie. But greatness would not suffer obstacles. One of the most significant advances in medical science began, therefore, in a sub-standard lab with bleach, a bucket, sponges, mops, and the sweat and labor of two great scientists.

Substandard lab conditions presented only one of many obstacles. After Banting and Best discovered insulin and proved that it could save the lives, they encountered trouble finding ways to purify and extract it. Macleod assigned chemist James Collip to the group to help with the purification. Collip solved the problem by removing harmful impurities from insulin while retaining its life-saving qualities.

Harmony did not reign among these great scientists, however. As the reality of a human trial became more plausible, Banting and Best raced with Collip to develop next steps. Macleod decided that Collip, as the best biochemist, would supply the purified extract. Because neither Macleod nor Collip was a practicing clinician, Dr. Walter Campbell oversaw the clinical administration of the trial, under the direction of Professor Duncan Graham.

When Banting learned of the plan, he was furious. He assumed he would be the one to administer the first clinical test. Macleod argued that when human life hung in the balance, precedence became irrelevant. Succumbing to pressure, however, Graham reluctantly agreed to use Banting and Best’s extract, despite its being less pure than Collip’s. Amid this high drama and posturing, doctors admitted Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old diabetic boy, to Toronto General Hospital on December 2, 1921. The boy received “Macleod’s serum,” which rendered inconclusive results.

When Collip heard of the reversal of the plan, he considered it a personal betrayal. Banting told everyone the trial had failed because the quantity had been insufficient, voicing his tale of injustice and tribulation loudly and indiscriminately. Graham encouraged Macleod to dismiss Banting, which Macleod found impossible to do because of Banting’s supporters. At one point, Macleod commented to his wife that he should start taking a chair and whip to work to tame the lions on his team. (Considering Banting eventually resorted to fisticuffs in his attempts to communicate his displeasure with Collip, Macleod’s lion-taming solution might have proved useful!)

During all this tumult, the science continued on two tracks: research and clinical. On January 23, Campbell began injecting Thompson with Collip’s extract. As the boy had been near death, those involved saw his recovery as nothing short of miraculous.

Banting and Best published the first paper on their discovery a month later, in February 1922. Although Macleod had left the laboratory and did not participate in the work, in 1923 the Nobel Prize was awarded jointly to Banting and Macleod “for the discovery of insulin.” Once again infuriated, Banting thought Best, not Macleod, should have received a share of the award. Banting finally agreed to accept the prize but gave half his share of the money to Best. Macleod, in turn, gave his share to Collip.

Very soon after the discovery of insulin, the medical firm Eli Lilly, and American global pharmaceutical company started large-scale production of the extract. As soon as 1923, the company began producing enough insulin to supply the entire North American continent, which positioned Lilly as one of the major pharmaceutical manufacturers in the world.

The story of this miraculous discovery, which began with a team of Canadian virtuosos who fought each other both literally and figuratively, has a happy ending; but few involved would have characterized the experience as pleasant, much less happy. People seldom find conflict resolution enjoyable. The rewards came from the keen dedication of the team members to accomplish the daunting goal of controlling the then-killer disease of diabetes. Two things allowed the research to become a reality: the exceptional talent of the scientists and the dedicated leadership of Dr. Macleod. Had either been absent, countless lives would have been wasted until a strong leader could have surfaced to orchestrate the efforts and conflicts of this team of virtuosos.3

Communication

During game six of the 2011 World Series, Cardinals player Matt Holliday made an error that would have embarrassed a high school player—he dropped an easy fly ball to left field. As he and Rafael Furcal collided, the game looked more like a ThrFF 4Uooges episode than a competition involving world-class athletes. Why? Two words: “It’s mine.” Holliday didn’t say them.

The same thing happens in organizations every day. So called “teams,” which really resemble committees, fail to determine areas of accountability among their players. Metaphorically, they too drop the ball because no one steps up, yells “Mine!” and makes things happen. Instead, members of the group plod along, neglect defining roles, overlook common goals, and don’t hold themselves and each other accountable. This sort of behavior, typical though it may be, frustrates nearly everyone, but it de-motivates top performers who want to play a bigger game—one where people don’t drop the balls.

What’s a leader to do? During the game in question, then-Cardinals coach Tony La Russa looked down and shook his head. My baseball expert adviser son-in-law, Pat, tells me he probably also cussed. Neither strategy will help your team.

As I mentioned in Chapter Two, history has shown us repeatedly that although conflict can impede a team’s progress, overly harmonious communication does not hold the key to success, either, when it results in groupthink—a communication phenomenon that helps explain why the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion failed.

Banting and Best illustrate the problems teams face when they don’t learn to address conflict effectively; decision-makers on Kennedy’s team show us that too much harmony creates its own impediment. Open, honest, responsive communication supplies the missing link—that connection that allows stars to go beyond ordinary solutions and results.

A building full of virtuoso talent who won’t communicate with each other won’t help you any more than average talent would. If you truly need and want a team, reward them as a group. Hold them accountable to team results, not just individual contributions. Tie their bonuses and compensation to their work as a team. One player can’t go to the World Series, and neither can one of your team members carry the others.

Clear Objectives

When exceptional individuals join together in the pursuit of a common goal, miraculous things can happen. Sometimes an exceptional leader can recast the ordinary into the extraordinary, as George Washington did at Valley Forge, but more often marvels occur when leaders have stellar talent to start with. That happened at the Winter Olympics in 1980.

The U.S. victory over the long-dominant and heavily favored Soviets quickly earned the title the “Miracle on Ice,” the event many consider the greatest sports moment of the past century and what Sports Illustrated called “the single most indelible moment in all of U.S. sports history.”

What made it miraculous? To begin with, the U.S. hockey team entered the games seeded seventh out of 12 teams that qualified for the games. Second, composed of collegiate and amateur athletes, the U.S. team faced a formidable opponent in the well-developed, legendary Soviet players who had won the gold in the previous four Olympics.

Even though the U.S. team faced overwhelming odds, it did not put less-than-stellar players on the ice. The romantic notion that a bunch of college scrubs felled the world’s greatest team through sheer nerve and determination is both misguided and inaccurate. The United States started with star performers—even though these stars had not garnered fame or press up until the Olympic Games.

The team also had a determined coach in Herb Brooks who had spent the 1970s as head coach at the University of Minnesota, leading that team to three NCAA titles. Brooks spent a year and a half nurturing the Olympic team, holding numerous tryout camps before selecting a roster from several hundred prospects. The team then spent four months playing a grinding schedule of exhibition games across Europe and North America.

Brooks emphasized speed, conditioning, unusual tactics, and discipline, but not popularity. Known for his prickly personality and fanatical preparation, Brooks united the previous rival players—often against himself. The team shared a common enemy in the locker room as well as on the ice.

The Americans entered the games as the underdogs, but they formed a team of competitive canines. From the hundreds of hopefuls, Brooks selected the 20 players who would go on to represent the United States in the miracle. Of the 20 players, 13 eventually played in the NHL. Five of them went on to play more than 500 NHL games, and three played more than 1,000 NHL games.4

Scrubs? Underdogs? Second best? No, the U.S. team was nothing short of a team of virtuosos. Brooks, a talented coach and former player, united the team and produced a synergistic, miraculous effect. But before we notify the Vatican of this miracle, let’s keep in mind that Brooks started with impressive raw talent.

Business leaders do well when they learn lessons from sports greats. Athletic coaches never attempt to “save” players who can’t produce. They cut them. These coaches know they can’t win unless they put the best available players in the game. They patiently wade through hundreds of applicants to find the select few who can deliver miracles. Then, they steadfastly commit to developing the talent. It doesn’t happen every time—just every four years, when the best in the world compete with other virtuosos of their ilk. Maybe we should make it happen more often in our businesses.

It doesn’t happen because of unclear objectives. Members of an athletic team may have personal agendas (I want to score the most baskets; I hope to gain the attention of a scout, etc.). But winning teams don’t let these goals stand at cross purposes with the team’s objective: win the game. In business, unless the leader articulates a clear direction for the team, there is a real risk that different members will pursue their own agendas. The top scorers on the team may be the stars that shine the most brightly, but they and everyone else know they need the assists and defensive maneuvers of their teammates. Only through collaboration can stars win a team sport.

Collaboration

When tackling a major initiative, like a merger or acquisition, leaders realize they need to assemble a diverse team of highly successful individuals—and then force them to work together. A team composed of dissimilar, highly educated specialists often holds the keys to the success of the challenging initiatives. Paradoxically, the qualities required for success are the same factors that will undermine success, as the aforementioned examples indicate. Complicated projects demand different skills, but we tend to trust most those who share the most in common with us. Similarly, complex endeavors require highly skilled participants, but they tend to fight with one another, as we learned from the team that discovered insulin. When success hinges on cohesive efforts, leaders need to uncover ways for specialists to work together, under high pressure, in a “no retake” environment.

What levers can executives pull to improve team performance and collaboration? In their study of 55 teams that demonstrated high levels of collaborative behavior, despite their complexity, researchers Gratton and Erickson uncovered eight things leaders can do to build collaboration:

1. Invest in facilities and methodologies that foster communication.

2. Model collaborative behavior.

3. Mentor and coach to help people build networks they need for success.

4. Teach communication skills.

5. Support a strong sense of community.

6. Assign team leaders that are both task-and relationship-oriented.

7. Put a few people who know each other together.

8. Clarify roles and tasks.5

Strengthening an organization’s capacity for collaboration requires a combination of long-term investments in building relationships and trust, and in developing a culture in which leaders model cooperation. It won’t happen automatically, but through careful attention to the eight functions of a virtuoso team and the eight things that build collaboration, leaders can solve complex business problems without inducing the destructive behaviors that can accompany the collaborative efforts of stars.

Leadership

Formation of a top performing team relies on two kinds of leadership: the external leader and the shared leadership that exists among the team members. Think of the external leader as the coach of the athletic team. The coach’s most important responsibilities involve selecting the team, training them, and then guiding them during the game. At the start of the game, the team huddles around the coach for final words of motivation, but once the buzzer sounds, the players take the field to perform—dependent on each other but independently of the coach. That’s when the shared leadership kicks in. Sometimes the balance doesn’t occur, however, and a team relies too heavily on the external coach.

That’s what happened at Milan High School in 1954 when a small-town Indiana basketball team won the state championship, a victory made famous by the 1986 film Hoosiers. In most states, high school athletic teams are divided into different classes, usually based on the number of students in the school, with separate state championship tournaments held for each classification.

In 1954, Indiana conducted a single state basketball championship for all of its high schools, which challenged Milan High School, with its enrollment of only 161, to play in competitions they’d never enter in today’s world. Milan was the smallest school ever to win a single-class state basketball title in Indiana, and it hasn’t happened since—in this case, providing an exception to the rule: an alchemy of external leadership and talent must occur consistently and continuously to ensure top performance over the long haul. Teams that rely too heavily on the external coach, and not enough on the talent of the members, can’t and won’t win over time. Similarly, top talent with no external leadership can’t hope to succeed either.

Milan High School hired Coach Marvin Wood two years prior to the famous victory, and with him came a new coaching style. He closed practice to outsiders, an act that angered many and removed one of the major forms of entertainment for the town’s basketball-crazed population. The coach had above-average talent, especially for a small town, and he expressed his amazement at the unusual scope of size and talent available among the many boys trying out for the team, talent forged by a strong junior-high program.6The team won the 1954 nail-biter championship by two points, but neither the players nor the coach enjoyed much distinction after that. The story provided the backdrop for a feel-good, tear-jerking movie, but teams in organizations have to do better. They have to win the game repeatedly, and preferably by more than two points.

Remember that, unlike a sports team, in an organization a team of stars doesn’t work together as much as it thinks together. Traditionally people have focused on a division of labor in work groups; however, top-performing teams require a shift in paradigms—a movement toward and focus on a division of knowledge. The knowledge that each member offers forms the foundation of that person’s contribution and reputation. The collective resources, therefore, of the team combine to explain its resourcefulness.

Teams of stars initially respond favorably to the external leader’s direction—and then they don’t. They proceed unfettered until they hit an obstacle, the time when leadership among the members becomes most important. These obstacles can be related to content, procedures, interpersonal interactions, or ethics. When they occur, leadership related to influence rather than dominance, along with effective communication skills, provides the path around or over the obstacle.

In my work with teams of stars, I have found these obstacles most often related to fuzzy accountability. Either the team never took the time to outline decision-making responsibilities, or a member attempted to stray away from the agreed-upon protocol. When I encourage them to invent, reinvent, or revisit the accountability discussion, usually the problem fades. But not always. That’s when the external leader needs to jump in.

Mountains of research exist to explain why and how leaders emerge in groups. If you have assembled a team of stars, however, disregard all of this. Stars form teams differently for many of the aforementioned reasons, and they share leadership differently, too.

During the initial stages, stars vie for “smartest person in the room” status. Dominant and forceful, stars have grown accustomed to acting as the go-to person in their departments. Others have learned to rely on their expertise; their self-reliance and independence have explained most of their success. Just as they don’t readily join teams in the first place, stars don’t gladly abdicate power and position. Yet they don’t want to collaborate with “B” players either.

Leading the Luminaries

When it comes to accepting direction, star performers show caution and restraint. They offer raw talent, expertise, discipline, and excellence, so they want to see the same qualities in those who lead and teach them. Members of the St. Louis Cardinals see these traits in their hitting coach, John Mabry.

Mabry, a former Major League Baseball player, had 898 career hits in 3,409 at-bats, for a batting average of .263. That included 96 home runs and 446 RBI. During his 14-year MLB career, Mabry played for eight teams, including three different stints with the Cardinals. In December 2011, he joined the Cardinals as assistant hitting coach and, in 2013, took the position of hitting coach. In his first year as hitting coach, the Cardinals made it to the World Series, and the team set a new baseball record for hitting efficiency with runners in scoring position.

Like the highly trained instructor pilots of TOPGUN, to whom I referred in Chapter Four, when they seek a coach, professional sports teams rely on stars who have proven track records of success. Because these exceptional performers know what it takes to succeed, they can impart their wisdom to those who come after them. But how? How do these legends in all professional sports pass on their knowledge and talent to the next generation? And why do they succeed so admirably in sporting venues when so many fail to reach the same level of stellar coaching in corporate settings? I asked John Mabry.

Baseball legend Yogi Berra once said, “Ninety percent of the game is half mental.” Mabry agrees. By the time a major league player asks John Mabry for help, the player has established his talent. Every star player on the field has talent—copious amounts of it—or no one would have given him a chance to be there in the first place. But, according to Mabry, that doesn’t separate the stars from the “also rans.”

When the coaching staff looks at a young recruit, nods in agreement, and states, “He gets it,” they mean he understands how to work within the parameters and demands the game will require. He will have to handle success and failure, manage his time wisely, draw on inner motivation, and, most importantly, self-regulate. These players understand that once the season starts, they will usually have one day off a month, and if the team goes into post-season play, even that day can disappear.

Professional ball players have to do the same things every other star performer has to do: balance work and family, perform when they’re tired or don’t feel good, work long hours with people (whether or not they like them)—but professional athletes have do it all with the cameras rolling. They have to have the confidence to walk out on the field and deliver consistently above-average performance—as compared to other star athletes who make that average pretty high—and do it all without developing the arrogance that they have nothing left to learn.

Those who “get it” understand that they will have some of the world’s best coaches to help them but that the discipline and humility to ask for that help has to come from within. According to Mabry, for coaching to be effective at this level, it must be 100-percent player-focused. The coach must wait for the right time to give feedback. (When a player returns to the dugout after striking out, he doesn’t want to hear insights about what the pitcher is throwing, for example.)

Mabry doesn’t have a “one size fits all” approach to coaching. Rather, he studies each player for dozens of hours to learn what to say to whom. Each hitter needs a slightly different approach, and each individual person often needs a different style, depending on what else is going on in his life. Overall, however, Mabry does believe in the power of positive reinforcement and accentuating the player’s strengths.

As Mabry pointed out, above all, the player must trust the coach. The kind of trust Mabry described harkens back to the four constructs of trust I offered previously. The player will ask himself, “Do you have the integrity to keep my confidences, the expertise to teach me, the predictability of your performance and responsiveness, and a sincere belief that you care about my success?” Answers to all questions must be “yes.”

Mabry offered the following advice to those in business who would like to improve their own coaching:

• Coach with empathy. Think about what a person is going through and meet him there.

• Move your company in the right direction, not just the direction you want it to go.

• Communicate to others your vision and desire to do what’s right for everyone, not just yourself or a chosen few.

• Think of coaching as serving others.7

When I coach executives for promotion, one of the objectives we almost always address involves their need to give more coaching and feedback to their direct reports. Most of the executives have played sports, so intellectually they understand the importance of receiving constructive feedback. No Little Leaguer would ever meet John Mabry or those like him if it weren’t for dedicated coaches who took the time to watch the swings, give correction, and pat a back. They all know this intellectually but fail to translate their experiences to the corporation. When the stakes are the highest, and the person has the most to lose, the coaching and support vanish.

Leaders who aspire to lead exceptional organizations know they have to do better. They understand that they can observe gold standards of coaching all around them by turning on the television during virtually any season and witnessing the hard work these professional coaches put into the development of others. Leaders who find themselves fortunate to have stars in their organizations know they can’t rely on hands-off, laissez-faire leadership. The stars won’t shine without the leader’s help or each other’s. Top performers want to win the World Series of your industry, and ordinary leadership won’t allow that to happen.

Conclusion

Creating your galaxy begins with a constellation of stars—people whose performance distinguishes them from the ordinary and whose gravitational pull allows your organization to serve as a magnet to other stars in the solar system. It all starts with the individual but quickly becomes more about the stars orbiting one another in a way that builds cohesive, collaborative efforts.

Building a team of exceptional people involves appreciating how individual members’ characteristics and personalities unite to form the unique culture of a top-performing team, but research repeatedly tells us that stars tend to be strong solo contributors who would prefer to work alone. Yet no one person can win the World Series nor can one person create a symphony, so these exceptional people soon learn that only through collaboration can they achieve their greatness. Successful business leaders understand that they must build cohesion among disparate personalities and functions. Only then can the organization achieve the success that will guarantee that the virtuoso stays and performs well.