2

Management and Ergonomic Approaches toward Innovation and Design

2.1. History and definition of strategy

Complementary to Chapter 1, the purpose of this section is to provide a historical strategy perspective on ergonomics as certain events in the development of business strategies have a human impact which to some extent challenge the traditional view on strategy. For example, stakeholder involvement, value chains, resource-based views (RBV) [BAR 91], dynamic capabilities [TEE 97], etc., have impacted the definition of strategy1 towards being more comprehensive and context driven. According to Nag et al. [NAG 07], strategic management deals with how major intended and emergent initiatives match the internal organization of companies and use of resources to enhance their performance. Moreover, developments in strategic management, where firms focus on pluralistic objectives, combined with a user-experience centered view on consumerism, gave rise to the design and development of intangible-dominant commodities, such as services. Successively, service innovation [MIL 93], service design, product service system development, etc., reemphasized the importance of a systemic approach in strategizing, where deliberate planning resulted in innovation activities, centered around the user. This user- or human-centered innovation approach shares the same perspectives with prospective ergonomics (PE) and is characterized by a focus on well-being, an orientation toward the future and business making, and a need for contextual embeddedness.

2.2. Management and design frameworks supporting PE

The purpose of discussing a selection of theoretical frameworks in this chapter is to anchor PE within the broader context of ergonomics and strategic management, as well as to explore synergies between this new field of ergonomics and strategic design. Figure 2.1 depicts the relationship between management, design and ergonomic topics, centered around PE.

Figure 2.1. Selected theoretical frameworks and methods to conceptualize prospective ergonomics

To form the foundation for this thesis, selected theoretical frameworks and methods from the fields of strategic management, product planning, strategic/system design and design reasoning feed into the main theme “prospective ergonomics”. These frameworks, which will be elaborated more in the following sections, are as follows:

- – technology push–market pull;

- – worldviews and design reasoning modes;

- – generic business strategies;

- – product service systems (PSS);

- – co-creation and human-centered design;

- – design-driven innovation.

2.2.1. Technology push versus market pull

As the global environment is becoming increasingly competitive and dynamic, organizations and businesses are continuously challenged to look for the most efficient ways to maximize their innovation and management efforts using new models, methods and paradigms, which efficiently serve existing and new markets with new and/or modified products as well as services [CHR 00]. Damanpour [DAM 91] has extended the definition of innovation beyond the creation and market introduction of new products or services by claiming that it can also be a new technology or structure to improve production and administrative systems, or a new plan or program to facilitate collaboration among stakeholders. This implies that in the pursuit of radical innovation, global trends need to be taken into account in the planning of future products, services and contexts [FIN 09]. Hereby, innovation push and pull models are helpful to characterize drivers for innovation. Traditionally, push-innovation referred to knowledge- or technology-driven innovation. Although technology push has been considered as a first and important generation of innovation strategy [ROU 91], design-driven innovation, originating from an internal knowledge-building within companies and among stakeholders and interpreters, has recently been advocated as most relevant in discovering hidden needs [VER 08, RAM 11].

Simplistically, managers of technological enterprises can be segmented in two camps: those who believe that markets direct their course of action and those who proclaim that their technology will develop a following [SUK 11]. Those who need to define a market beforehand are marketing managers while engineers and technologists adopt a more constructive approach. The range of recent innovations such as polyester tires, ceramic engines, superconductivity and personal computers challenge marketers and engineers to adopt both a positivist as well as constructivist approach. Can a marketing manager make a list of all of the inventions which he has never heard of? Similarly, can a technologist predict all applications (i.e. needs) for nylon or integrated circuits?

Given this context, firms, both large and small, require both technology-push and market-pull approaches in order to be continuously innovative and profitable.

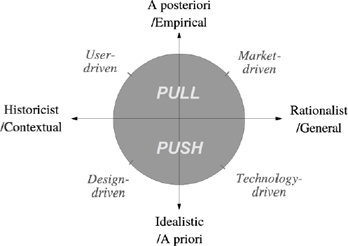

A matrix, juxtaposing rationalist-historicist and empirical-idealistic dimensions, illustrates the different relationships of technology-push and market-pull approaches with respect to four different types of innovation: user-driven, market-driven, design-driven and technology-driven2 (Figure 2.2) [LIE 12].

Figure 2.2. Rationalist-historicist and empirical-idealistic dimensions contextualized and positioned according to different technology-push and market-pull approaches (adopted from [MØR 11, p. 214]

A historicist view on innovation shows a more constructivist conception of the process as a whole, characterized by an iterative cycle of concept development and testing of solutions. A rational view perceives knowledge to be applied independently of a specific setting, at least to a certain degree. An empirical/a posteriori perspective represents a “pull” approach, whether market- or user-driven. This means that “data” are a prerequisite for a firm to initiate innovation. Supporters of the idealistic/a priori perspective are convinced that radical innovation should come from either a technology or design “push” approach. They are skeptical that breakthrough innovations can be systematically and empirically analyzed only through data.

However, technological developments and market structures are influential in how the product, system or service is being divided into interconnecting entities. As an example, Ansoff’s perspective on innovation strategy can be seen as an essential tool for directing market and technological research [ANS 80], whereas Mintzberg’s strategy model suits a context-based user or design-driven innovation process better [MIN 87]. Both perspectives are considered as equivalent to the push and pull models of innovation. The description is polarized in order to contrast the different models of innovation and to facilitate the positioning of different ergonomic interventions and specializations.

In user-centered innovation, product development activities start from a deep analysis of user needs, where researchers immerse themselves in fieldwork by observing customers and their environments to acquire a detailed understanding of customer’s lifestyles and cultures as a foundation for better discerning their needs and problems [BEL 04]. Latest developments in innovation activities involving users have questioned the creative effectiveness of user-centered design methods from a participatory design (PD) and generative design research perspective, characterized by co-creation methods [SAN 08]. PD is an approach to assess, design and develop technological and organizational systems, whereby active involvement of potential or current end-users as well as other stakeholders is encouraged in design and decision-making processes.

Similar to technology-driven innovation, design-driven innovation has largely remained unexplored. Moreover, unlike user-centered processes, it is less based on using formal roles, processes and methods, such as ethnographic research. Design-driven innovation may be perceived as a manifestation of a reconstructionist [MAU 05] or social constructionist view of the market [PRA 00], where the market is not “given” a priori but is the social construct of interactions between consumers and firms Hereby, stakeholders need to understand the radically new language and message, to find new connections and meanings to their sociocultural context and to explore new symbolic values and patterns of interaction with the product, which are not only livable and sustainable but also fun and culturally inspiring [ESS 11].

In other words, sociocultural regimes are profoundly solicited by radical innovations, similar to the way fundamental changes in technological regimes are devised by radical technological innovations [GEE 04].

2.2.2. Philosophical worldviews

Although philosophical worldviews remain most often largely hidden in the design world, they still influence the practice of design and need to be identified. As explained by Creswell [CRE 09] and Lincoln and Guba [LIN 85], a worldview can be defined as “a compilation of fundamental beliefs that guide action” and is similar to a paradigm or epistemology.

The types of philosophical worldviews held by individual designers will often have great impact on their approaches to design theories and indirectly on the concrete methods and techniques they use. Four different worldviews are briefly presented in Figure 2.3 [LIE 14], based on the work of Creswell [CRE 09] on research design (and the use of qualitative, quantitative or mixed research methods).

Figure 2.3. Overview of presented worldviews and design theories [LIE 14]

It should be noted that the presented worldviews may take various forms and may use principles that are comparable and complementary from one another. They are not considered as rigid and separate but rather may overlap each other to varying degrees. For the alignment of selected worldviews with ergonomic interventions, positivism and constructivism in their most literal form have been presented here as contradictive and irreconcilable (see Figure 2.3, [LIN 85]). However, one should note that according to “constructivist realism”, worlds are multilayered with many levels of interacting structures on-going simultaneously [CUP 01]. This is reinforced by the on-going trend toward the reconciliation of positivism and constructivism, which can be achieved by eliminating the arbitrary boundaries and assumptions concerning truth and apprehension. For instance, postpositivism offers a vision that is more nuanced and better suited for the study of design science; it recognizes that knowledge is conjectural and absolute truth can never be found when studying humans [PHI 00]. Constructivism is affiliated with postmodernism, whereby truth is perceived to be grounded in everyday life and social relations, and knowledge is created from different sources and experiences. It is significantly different from postpositivism because we are constrained by our own perception and as such cannot access reality and that which we consider to be reality is constructed. In other words, the observer and the observed cannot be separated; reality is co-constructed by individuals in a social context, where beliefs change over time [LIN 85].

Although pragmatism makes use of elements from both postpositivism and constructivism, it remains a worldview on its own and is not committed to one system of philosophy and reality [CRE 09]. Great emphasis is placed on focusing on a problem and the use of pluralistic approaches to derive knowledge about the problem. As researchers have the freedom to choose methods, techniques and procedures for research, stands are not taken on the debate of reality as objective or subjective but on how they best meet their needs and purpose [CRE 09, ROR 90].

Advocacy criticizes the fact that constructivism does not go far enough in advocating for marginalized people [CRE 09]. With respect to stakeholder involvement in a human-centered design context, individuals should be included in prospective ergonomic research and design in order not to be further marginalized or limited in self-determination and self-development.

The relationship between the different worldviews and PE can be argued from a “human” interest perspective. Understanding present and designing future contexts with respect to well-being as well as economic sustainability are most likely to be facilitated by adopting a constructivist, advocacy and partly pragmatic worldview in addition to positivistic ways of “doing things”:

- – the constructivist worldview contextualizes the fact that human activities are unpredictable and subject to external influences; social, economic and political, as well as internal ambitions, which can sometimes be erratic, illogical, idealistic, etc. In line with PE and strategic design, designers seek to capture the complexity of views instead of narrowing them to a few categories of ideas. Hereby, subjective meanings are socially and historically influenced, and research focuses on the contexts and interactions among individuals, which is different from postpositivist research where interpretation of observations is influenced by the background of the researcher;

- – the pragmatic worldview acknowledges that humans need systems and systematic planning but since they do not have an infinite knowledge framework, planning happens within predetermined contexts. These predetermined contexts are more supportive of a corrective or preventive way of solving ergonomic design problems, assuming that an ideology or proposition is true as long as it works satisfactorily;

- – the advocacy worldview connects well with PE, as it lays the foundation for developing persuasive concepts and socially responsible solutions to promote future well-being for people.

To summarize this section, the dual objective of PE, which is, on the one hand, to promote well-being and, on the other hand, facilitate innovation, requires designers and ergonomists to plan the development of products and services, while taking into consideration contextual constraints, possibilities and responsibilities. With respect to worldview adoption, these designers and ergonomists need to embrace all the four worldviews, because PE resides in systemic ways of strategizing (see section 2.3), where processes are deliberate and targeted outcomes are plural.

Section 2.2.3 maps out four generic strategies to provide a clearer picture why a systemic generic strategy is very much related to PE with respect to thought, process and ambition.

2.2.3. Four perspectives on strategy

The motivation behind a company’s vision and choice of strategy is usually encapsulated in various theories of action in order to achieve competitive advantage [WHI 01]. To provide decision makers with fundamentally different ways of thinking about strategy in a wide range of situations, four perspectives on strategy were created and mapped according to process and outcome (see Figure 2.4). These perspectives, which are classical, evolutionary, processual, and systemic, have their roots in “Mintzberg’s 10 Schools of Thought about Strategy Formation” [MIN 85]. As a precursor to Whittington’s generic strategy perspectives, these schools were compared and positioned on a bipolar spectrum according to planned and emergent strategies [MIN 89].

When addressing the “outcomes” axis, the “plural” dimension should be interpreted from a more nuanced perspective, considering both the short and the long term, as well as diverse ambitions of internal and external stakeholders, in contrast to the focused profit-maximizing aims of the organization leadership. The “processes” axis illustrates a spectrum between deliberate and emergent ways of planning.

Figure 2.4. Overview of generic strategy perspectives [WHI 01]

In the classical approach, profit-maximizing is the highest goal of business and rational planning. This classical theory claims that if returns-on-investments are not satisfactory in the long run, the deficiency of the business venture should be corrected or abandoned [SLO 63]. Key features of the classical approach are the attachment to rational analysis, the separation between planning and execution, and the commitment to profit maximization [ANS 68, SLO 63].

Evolutionary approaches are characterized by an on-going struggle for survival through reactive decision making. In the search for profit maximization, natural selection will determine who are the best performers and the ones that survive [EIN 81].

In contrast to classical and evolutionary approaches, processual methods do not aim for profit-maximization ambitions, but strive to work with what reality offers. Practically, this means that firms are not always united. Instead, individuals with different interests, acting in an environment of confusion and mess, determine the course of action. Through a process of internal bargaining within the organization, members set goals among themselves, which are acceptable to all.

In a systemic approach, the organization is not made up simply of individuals acting purely in economic transactions but of individuals embedded in a network of densely interwoven social relations that may involve their family, state, professional and educational backgrounds, even their culture, religion and ethnicity [WHI 01].

2.3. Aligning generic strategies with innovation approaches through worldview perspectives

Using different worldview perspectives, alignments can be established between Whittington’s generic strategy perspectives and the technology-push/market-pull innovation approaches, as shown in Figure 2.5. Although these alignments can be perceived to be rather simplistic, it explains the most dominant relationships between typical worldviews, strategy perspectives and innovation approaches. In each of the following four sections, the connection between (technology-push/market-pull) innovation approaches and generic strategy perspectives will be elaborated through a worldview transfer.

Figure 2.5. Alignment of innovation approaches with generic strategies through a worldview perspective

2.3.1. A technology-driven innovation approach based on a generic classical strategy

Besides sharing positivistic characteristics of “doing things in a top-down, structured and directive manner” between technology-driven marketing and classical strategy approaches, “good business model” design and implementation, coupled with careful strategic analysis, are necessary for technological innovation to succeed commercially [TEE 10, p. 184]. This statement implies that every new technology-driven product development effort should be coupled with the development of a planned business strategy, which defines its “go to market” and when and how to “capture optimal economic value strategies”. Based on a continuous spectrum, the following concrete examples show possible planned strategies which a company can adopt:

- – at one end of the scale, an integrated business model is being applied where an innovating firm takes responsibility for the entire value chain from A to Z including design, manufacturing and distribution by grouping innovation and product design activities together;

- – the other extreme case is the outsourced (pure licensing) business approach, which has been adopted by several companies;

- – in between there are hybrid approaches involving a mixture of the two approaches (e.g. outsource manufacturing, provide company-owned sales and support). Hybrid approaches are the most common but they also require strong selection and organization skills on the part of management [TEE 07].

2.3.2. A design-driven innovation approach based on a generic systemic strategy

In the broader context of creativity, design is the engine to manage complex human needs. Designers and their business partners have a unique obligation and opportunity to build an environment where actors, consumers, users and other stakeholders, are members of a larger interdependent community rooted deeply in densely interwoven social systems. Hereby, these actors should not be seen as decision makers, who are simply detached calculative individuals, interacting in a purely transactional manner in an economic sense [GRA 85]. To be more specific, people’s economic behavior is embedded in a network of social relations involving their families, state, their educational and professional backgrounds, religion and ethnicity [SWE 87, WHI 92]. This systemic view on strategizing aligns well with the concept of “design-driven” innovation and “technology-driven” innovation, which have earlier been explained in section 2.2.1.

Particularly in “design-driven” innovation, deliberate attempts to create radical change through meaning-making in the design of products and services have been promoted by Norman and Verganti [NOR 14] through their framework on technology–push innovation, market–pull innovation, meaning-driven innovation and technology epiphanies. This framework will be elaborated upon in section 2.8.5, upon contextualization with ergonomic domains, specializations and interventions.

The alignment between a design-driven market approach and a systemic way of strategizing is commonly represented by its context dependency. People in organizations strategize and consumers make sense of a product or service according to their psychological profile and the cultural and social context in which they are immersed. Interpretations of meanings are constructed and reconstructed in an ongoing co-creation process through continuous interactions among firms, designers, users and several stakeholders, both inside and outside a corporation [BRO 91, TSO 96]. The innovation of meaning, therefore, could be linked to a social constructivist [BUR 10, LAN 95] or even reconstructivist [CHA 05] approach, where the interaction of objects and subjects mutually “shapes” or “constructs” representations of reality in a continuous process. The constructivist transfer, which is hermeneutic in nature, suggests that innovation is the act of envisioning new meanings. It is not simply about generating ideas and solutions but about strategically creating a whole new vision. Hereby, the act of interpretation is based on a deliberate creation of new interpretations that do not yet exist by involving a broader range of interpreters and experts.

2.3.3. A user-driven innovation approach based on a generic processual strategy

The connectivity between a user/consumer-driven perspective toward innovation and how this is being facilitated by a processual strategy is dependent on how organizations transform themselves to become more consumer oriented. This transformation can take place when these organizations are willing to introduce novel tools, instruments and procedures to systematically and continuously integrate users into their core business processes. Enabling users to interact with each other in real time and reflectively exchange and discuss ideas or to provide feedback and support is a vital prerequisite for fostering creativity during ideation processes [HIE 11]. The link with the processual characteristics of strategizing is established by rejecting the existence of the rational man, as well as perfect functioning competitive markets [CYE 63]. Acknowledging the limits of human cognition, people within organizations and therefore organizations are rationally bounded. Similarly, users, who are involved in co-creating products, services and businesses, are unable to consider more than a handful factors at one time. Biased in their interpretation of data and limited in communicating all their needs, designers and ergonomists are inclined to adopt a reactive and reflective practice approach toward creativity and problem solving. To summarize this section, doing things in an evolving manner centered on people is a typical trait of user-centric strategizing when objectives are plural and stakeholders accept and work with the world as it is.

2.3.4. A market-driven innovation approach based on a generic evolutionary strategy

Supporters of the evolutionary perspective on strategizing are less confident that top managers and decision makers are fully capable of planning and acting rationally. By adopting a postpositivistic and pragmatic worldview, they believe that markets dictate how profit maximization can be achieved. By association with the “law of the jungle”, only the best performers will survive. Therefore, managers need not be rational optimizers because “evolution is nature’s cost benefit analysis”. However, this does not mean that companies need to take an ad hoc approach toward innovation [CLA 11]. They need to continuously connect with increasingly complex consumer demands as well as exploit the technological capabilities they possess, or acquire new ones. The differences with the other innovation and generic strategy alignments, such as the “user driven – processual” alignment, are that in this market-driven innovation approach consumer behaviors are essential but the consumer/user him or herself is not expected to be involved in creativity or co-creation activities. In other words, the consumer is seen as a passive rather than an active participator. From the offering point of view and based on the (dynamic) capabilities of the companies, the evolutionary way of strategizing is to maximize profit by betting on different incremental innovation projects and initiatives, rather than carefully planning a single penetration strategy for achieving “radical” innovation. The reason why certain companies choose to strategize in an opportunistic manner is based on their belief that it is becoming more difficult to predict the future because of globalization trends, changing economic, social and political climates, and increasingly complex consumer demands. Furthermore, companies are being increasingly subjected to dynamic internal and contextual demands, which makes it extra challenging for decision makers to plan future products and services.

2.4. Toward integrated thinking in PE: relating C-K design theory, generic strategies and design reasoning models

In this section, C-K design theory, generic strategies and models of design reasoning will be discussed within the context of management and design thinking to develop the argument that PE is founded upon “integrated thinking”. In developing this argument, it is necessary to juxtapose C-K theory with generic strategies, on the one hand, and C-K theory with models of design reasoning, on the other hand. Juxtapositioning leads to the following:

- – in concurrence with Hatchuel’s work, strategic management is challenged to become more pluralistic by aiming to be inclusive, human centered and empathic in seeking co-created solutions to problems [HAT 10, p. 11]. Hereby, design thinking around business making may facilitate pluralistic ambitions, as it builds on principles of integrative thinking;

- – with respect to different modes of design reasoning and philosophical worldviews, abductive logic that lies between “the past-data-driven world of analytical thinking and the knowing-without-reasoning world of intuitive thinking forms the basis for “integrated thinking” [MAR 09, p. 26];

- – the meaning of “integrated thinking” for PE is that positivist and constructive worldviews, as well as problem solving/pragmatic versus reflective/hermeneutic ways of reasoning may alternate in the search for future innovative products and services. In other words, this dualistic way of reasoning based upon supposedly contradictory worldviews and immersed in a systemic generic strategy, bounded by rationality, describes the main characteristics of PE.

Referring to the qualities of C-K design theory with respect to the above three points, I believe it is most appropriate to elaborate on C-K design theory [HAT 03] to justify the interconnectivities among worldviews, generic strategies and models of “design” reasoning [LIE 12].

2.4.1. C-K design theory

Hatchuel and Weil [HAT 03] introduced concept–knowledge theory (or C–K theory), which has gained significant academic and industrial interest over the past 10 years. The theory is based upon the understanding that concepts are generated from existing knowledge, as well as that knowledge is explored through concepts [HAT 10]. Recently, features of this theory have been recognized as being unique for describing creative reasoning and processes in engineering design, highlighting the fact that one of the most noticeable features of C–K theory is founded on the notion of a creative concept [ULL 12]. Hereby, two discourses of strategy as design have been introduced [HAT 10, p. 12]: “strategy as analysis and implementation” and “strategy as innovation”. Similar work in the field of architecture has been undertaken by Bamford [BAM 02], where analysis/synthesis has been rejected in favor of conjecture/analysis.

A key issue in C–K theory is how designers, managers and other stakeholders evaluate dependencies between what is yet-to-exist (a set of variants for a seed project with innovative elements) and what is known (and hence, what can be used as a resource for the design process). The claim of the theory is that this conceptual reasoning process is about defining essential characteristics of design, which is fundamentally different from processes prevalent in formal sciences (i.e. deductive or inductive processes) [AGO 13]. In other words, to offer a perspective where creative thinking and innovation are to be included within the core of design theory is to provide a logical and precise definition of design [HAT 03, pp. 1–2].

More concretely, design can be perceived as a coexpansion activity from two spaces: spaces of concepts (C) and spaces of knowledge (K). The expansion is transitional and can be noted as C⇒K and K⇒ C. With reference to the “design square”, knowledge can be expanded internally at a concept level through inclusion or partition as well as at a knowledge level through deduction and experimentation. Transformations from K⇒C, which are “disjunctions”, are typical characteristics of a positivistic problem solving process in design. Reversely, a transformation from C⇒K, which is a conjunction, can be perceived as a constructivist move toward the expansion of the knowledge space. At this point, it is too early to make clear connections and alignments between C–K theories and generic strategies. However, in terms of worldview positioning, the K⇒K and K⇒C transformations are typically positivistic and pragmatic movements, whereas C⇒C and C⇒K movements are driven by constructivism and advocacy. For example, the emergence of crazy ideas may have found their roots in spontaneous and ad hoc inspirations or suppressed beliefs concerning social, political, economical, ethical, etc., issues.

As anticipated in section 2.5, the contribution of C–K theory to PE is relevant because it involves different worldviews and models of design reasoning. For example, K⇒C⇒K movements are driven by positivism and pragmatism followed by constructivism and advocacy.

2.4.2. Six models of design reasoning

The adoption of Lie’s categorization is based upon how the authors view the current discourse, which demarcates theoretical traditions with respect to models of design reasoning. Lie’s extensive literature review has led to a systematic framework [LIE 12, p. 68], which illustrates the current dispute between positivistic/deliberate design approaches on the one hand and the more plural, reflected and embedded design approaches on the other. The way Lie has managed to make the dispute explicit will be relevant for design practitioners and researchers for taking stands in the “strategic” design of new products. The six models of design reasoning are “problem solving”, “hermeneutic”, “reflective practice”, “participatory”, “social” and “normative”.

In this section, models of design reasoning and worldviews will be discussed and aligned with a generic strategy framework [WHI 01]. This framework shows existing relations and conjectures among these theories (see Figure 2.6) which are necessary to justify the close relationship between design thinking and business strategizing. Furthermore, this integrated framework argues that service design and the design of PSS are typical fields which meet the characteristics of a pluralistic way of strategizing. Complementary to this pluralistic way of strategizing, human-centered management and design methods are being advocated to promote the design of products and services.

Although processes and outcomes are different for strategizing and designing, the understanding of similarities among different generic strategies, worldviews and models of design reasoning will be invaluable for ergonomists, designers and business managers to create better products, systems and services. This understanding will lead to an appreciation that strategic perspectives and design reasoning modes are somehow similar in nature in the exploration of innovation attitudes. Furthermore, this alignment will provide a better understanding on how to position ergonomic domains, interventions and specializations relative to strategic management, strategic design and industrial design theories. The following sections will elaborate more on these similarities.

Figure 2.6. Extension of generic strategies to models of design reasoning based upon philosophical worldviews ([LIE 14], adapted from [WHI 01, Figure 2.1, p. 10])

A positivist worldview underpins the classical strategy approach, where profit making is planned and commanded. This is in line with a focused and structured problem-solving approach, where a systematic design process [ROO 95] defines the solution space. The normative reasoning model is exemplified by how a strict and concrete program of requirements complements this problem-solving approach. Typically, PMT-matrices [ANS 68] and style/technology maps [CAG 02] are examples of methods and tools which support a planned and structured approach toward innovation and design.

The evolutionary and processual strategic approaches are built upon a pragmatic worldview. Lacking a debate as to whether reality is objective or subjective, the emergent and in some cases opportunistic characteristics of these strategies determine how organizations behave to achieve their profit-making targets or goals. For instance, within corrective ergonomics, an evolutionary business strategy, complemented by a reflective way of designing, would suffice to incrementally improve ergonomic functionality of existing products.

Similarly, there are design-reasoning attitudes which can be aligned with these emergent approaches. The reflective practice addresses design issues from a constructivist, though pragmatic, perspective by engaging in conjectural conversations with the situation [SCH 95]. The participatory element, where different stakeholders are actively or passively involved in the design process, bringing along their personal interests, is a real-life and pragmatic phenomenon, which aligns well with an emergent strategy driven by pluralistic objectives but which may not always lead to profit-maximizing or optimal, economical design solutions. To address such a complex situation, which emphasizes well-being, PE may facilitate the discovery of hidden needs and anticipate future solutions.

The systemic strategy is socially constructed and therefore the reality is coconstructed by different stakeholders and individuals in a social context [LIN 85]. Although processes are planned and deliberate, multiple objectives exist because of the complexity of multiple views, which are socially, historically, culturally and contextually embedded in respective communities of practice. Considering a community of design practitioners, the use of selected methods and tools, combined with personal experience and subjectivity, occupies a central place in the design process, which is based on hermeneutic and social reasoning. From PE and strategic design perspectives, the designer attempts to anticipate human needs and activities so as to create new artifacts and services that will be useful and provide a positive user experience [ROB 09]. Reiterating the importance of systemic embeddedness, contexts, values and functions should be considered here as a key element in getting any collaborative process going that involves different stakeholders.

2.5. A PSS perspective

As technological products continue to converge and become increasingly more important in consumer’s daily lives, service expectations continue to rise. This trend instigated a shift from production to utilization, from product to process, and from transaction to relationship [VAR 08], demanding a PSS thinking perspective toward ergonomics.

Complementary to this PSS view on ergonomics, Dul et al. [DUL 12] identified that the potential of human factors (HF) is underexploited because stakeholders in design and management of organizations are mainly focused on performance outcome. Even though there is some recognition among design and engineering practitioners and researchers about the potential benefits in applying HF in design, it is not sufficient [BAN 02]. The lack of HF being applied in design is also explained by Hollnagel and Woods [HOL 05]. Traditional ergonomics never questioned the validity of the human–machine distinction and therefore encountered problems in developing a systems view comprising stakeholder interactions in context.

As such, Norros [NOR 14] perceived a pressing need for conceptual innovation. This means that within a systems frame of reference, HF is to be design-driven as well as focused on two closely related outcomes: “performance” and “well-being” [DUL 12, p. 1].

In this context, the design of a system should be comprehended as a process of continuous redesign, where actors are involved in reconstructing and modifying the system in the course of their daily activities. Based upon the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theories [TEE 97], the basis of learning processes are derived from handling the many deviations from “the normal” procedure assumed by the designers [WEI 99]. This implies that over time system actors inevitably also play the role of system redesigners.

Based upon consumer-centric and plural intraorganizational perspectives [MIC 08], companies are challenged to conceptualize PSS that are perceived as valuable by all, extending the service-dominant logic to a larger, complex network of collaborating actors [VAR 08]. With respect to the deliberate modes of business strategizing, trends influencing PSS will be elaborated in this separate chapter to address the importance of a balanced approach in achieving performance and well-being within the context of strategic design and PE. The emergence of these trends can be attributed to the increasing complexities of technology and customer demands, driven by globalization. A systems approach, which concerns all stages of planning, designing, implementation, evaluation, maintenance and redesigning [JAP 06], matches with the ergonomic intervention on the product development process of Nelson et al. [NEL 12] (see Figure 1.2). Centered on design, these stages are not necessarily sequential; they are recursive, interdependent and dynamic. Decisions at one stage may influence or be influenced by decisions at other stages. This means that systems change because of the fluidity of the human or the environmental part of the system or both. However, ergonomics has the potential to contribute to the design of future systems by contributing fundamental characteristics through explicit design approaches, methods and tools as well as implicit modes of interaction in the search for innovative product and service design solutions in the fuzzy–front end stages of the design process.

In order to plan an effective innovation strategy for the future, key global developments and trends, as well as their significance for ergonomics, need to be identified through analyses and assessments resulting in recommendations and actions [HEN 91, JAP 06]. Without being complete, important issues that impact ergonomics are “global change of work systems”, “cultural diversity”, “aging”, “information communication and technonology (ICT)”, “enhanced competitiveness and the need for innovation” and “sustainability and corporate social responsibility” (CSR). These issues will be discussed in the following sections with respect to PE and strategic design.

2.5.1. Impact of global economic changes on work systems

Over the past decade, significant shifts in the types of work that occur in different regions of the world have been motivated by global changes in the economic landscape. These changes have taken place in both economically advanced nations and economically developing nations. Historically, economically advanced nations have been mass-producing goods. However, due to global market forces and the intensification of supply chains, these nations increasingly outsourced manufacturing and service functions to economically developing countries over the past two decades [DUL 12]. The emphasis in economically advanced nations has then shifted from a production to a service economy (including healthcare services), resulting in a greater focus on both the design of work systems for service production, as well as on the design of non-work systems such as services for customers and human–computer interactions [DRU 08, HED 08].

At the same time, developing countries have enlarged their economic activities through low-cost manufacturing of goods, as well as simultaneously experiencing an increase in low-wage service sector jobs (e.g. call centers, banking) [CAP 08].

Furthermore, the continuing trend of mechanization and automation of work systems, resulting in increased capabilities of technology, not only impacts the manufacturing but also service industry [SCH 09]. These phenomena changed attitudes and perceptions among stakeholders who are providing and receiving services whether or not they are complemented by products.

2.5.2. HF and cultural diversity

In many economically developed and developing countries, the understanding of the human element requires knowledge of complex, social and cultural environments. This can be attributed to global change, which proved to be instrumental in increasing interdependencies among economies, industries and companies worldwide. Consequently, production and distribution systems are internationally structured by implementing culturally diverse workforces to facilitate that products and services are consumed by increasingly diverse groups of customers in markets around the world [DUL 12]. As a result, (work) environments and product–consumer systems that were properly designed for one society may not be appropriate for other societies because of different cultural backgrounds, different characteristics and aspirations.

This trend of cultural diversity positions ergonomics within a systemic management strategy by contributing to the cross-cultural design of production, distribution systems as well as products and services that fit the diversity of users and other stakeholders [MOR 00, JAP 06]. In crosscultural design, it is generally agreed upon that people from different cultures have different capabilities and aspirations, which affect the design of the product–service systems in which they take part.

2.5.3. Demographic change

A demographic change is generally experienced in most developed parts of the world, brought about by a combination of longer life expectancy, declining fertility and the progression through life of a large “baby boom” generation [DUL 12]. In the United States and Europe, the proportion of older people in the workforce is increasing more than in other continents, whereas in India, Asia and especially Southeast Asia, the retirement age of office and industrial workers has recently been raised. As a result, a large group of senior workers has become part of work and product/service environments that were initially designed and more suited for a younger group of people. Implications are that work systems comprising equipment, furniture, IT devices, services, etc., need to be reevaluated and targeted to an older population and adapted to their characteristics, without stigmatizing them. Hereby, ergonomists need to take into account age-related changes in physical, cognitive, visual and other capabilities, and different aspirations [JAP 06].

Prospectively, there is room for developing more versatile systems that are better matched to a wide range of groups. As such, a universal design approach does not only apply to people of different age groups but also to people with disabilities [BUC 11].

2.5.4. Influence of ICT in shaping future living

According to Karwowski [KAR 06], several ICT-related challenges impact the manner in which work and activities of daily living are performed. For instance, rapid and continuous developments in computer science, telecommunication and media technology have increased and accelerated information transfer through new interactive activities such as social media and gaming. As a result, people’s social and working lives have become more and more dependent on ICT and virtual networks. In addition, product quality is valued beyond usability by emphasizing emotional design and pleasurable interactions.

ICT developments have brought about many changes in work organization and organizational design. For example, in the manufacturing sector, increasingly, organizational networks and supply chains are relying on virtual arrangements to communicate and share information. Another example resides in healthcare, where different healthcare organizations share information about patients.

Within the context of ICT, ergonomic specialists contribute to the design of virtual sociotechnical systems to engage diverse people who are geographically dispersed. They facilitate the use of information and communication technologies among these people to perform their work remotely and share information across organizational boundaries [WOO 00, GIB 06]. However, one of the many challenges is how to design natural user interfaces and influence the design of virtual sociotechnical systems in human–computer interactions, which can enhance trust and collaboration when team members work remotely and communicate via technology [PAT 12].

2.5.5. The need for innovation to enhance competitiveness

Globalization has forced companies to develop new business strategies and alliances to become more competitive. Additionally, it has also pressured companies to increase innovation and invention of new products and services, as well as new ways of producing these. To be successful in the market and to gain commercial advantage, these products and services must be of high quality and serve beyond technical functionality, for example by adding value in terms of positive emotional user experiences. Complementarily, production processes need to be more efficient and flexible and must guarantee short product delivery times, often resulting in intensification of work.

In the process of renewing business strategies and product/service innovation, ergonomics enhances and fosters employee creativity [DUL 11, DUL 09] as well as facilitates in developing new products and services with unique usability and experience qualities. It can also assist a company to innovate processes and operations by providing new efficient and effective ways of producing these products and services [BRO 97, BRU 00].

2.5.6. Sustainability and CSR

Sustainability, which deals with the needs of the present without compromising those of future generations, not only emphasizes natural and physical resources (“planet”), but also human and social resources (“people”) in combination with economic sustainability (“profit”) [DEL 10, PFE 10]. Rather than purely focusing on financial performance, it claims that companies act to fulfill a broader range of pluralistic objectives. For example, being corporately and socially responsible, companies take up the challenge to meet the minimum legal expectations regarding “planet” and “people”. A company’s image with respect to CSR may be damaged by poor or minimum health and safety standards, which would be a direct threat to the continuity of the business. Given this challenge, ergonomics can support sustainability and CSR activities within organizations by adopting a forward-looking approach in developing programs that combine the people and profit dimension through the optimization of both performance and well-being [PFE 10, ZIN 05].

In conclusion, global developments, which have been discussed in sections 2.6.1–2.6.6, argue for the need for a new type of ergonomics, namely PE, which focuses on managing and solving complex societal issues. Besides being systems oriented, this type of ergonomics should also be forward looking in time, because these developments continue to have future implications. Moreover, by taking a proactive role in shaping future living and working environments, PE requires taking responsibility for cross-disciplinary work [NOR 14]. For example, the intervention of PE in strategic design provides ample opportunities for collaborating with the design research as well as design community, which may lead to a richer collection of concepts for anticipating future living and working conditions.