17/

Microsoft Xbox

Halo 3

TAG/McCann Worldgroup San Francisco

When Microsoft released its third game in the Xbox Halo series in 2007, it wanted its marketing to do more than simply sell the product. ‘Halo 3 aimed to be the biggest entertainment debut in history,’ says Taylor Smith, global communications director at Microsoft. ‘We wanted to make an entertainment statement – this is gaming, gaming has arrived as an entertainment medium, think about it in the same vein that you think about blockbuster movies.’ This was no small ambition. While video games have achieved a huge cultural impact, influencing everything from cinema to advertising, there is still often a perceived computer games ‘type’. This is particularly true when it comes to the genre of science fiction war games, the territory that Halo is in.

‘Halo 3 aimed to be the biggest entertainment debut in history. We wanted to make an entertainment statement – this is gaming, gaming has arrived as an entertainment medium, think about it in the same vein that you think about blockbuster movies.

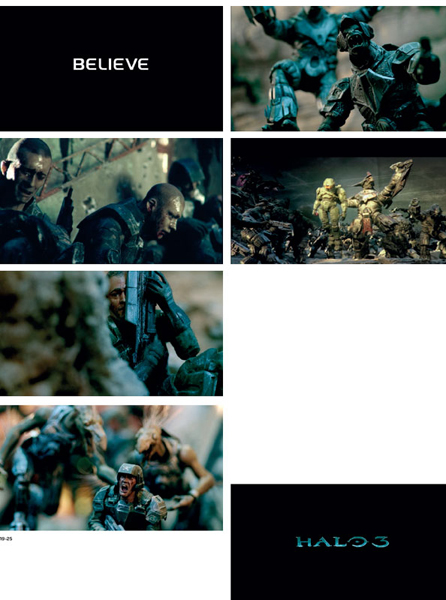

01-02 At the heart of the complex Halo 3 campaign is a film depicting an epic battle. Rather than filming with actors, the war scenes were handcrafted using tiny figures on a giant diorama; these images are stills from the final film.

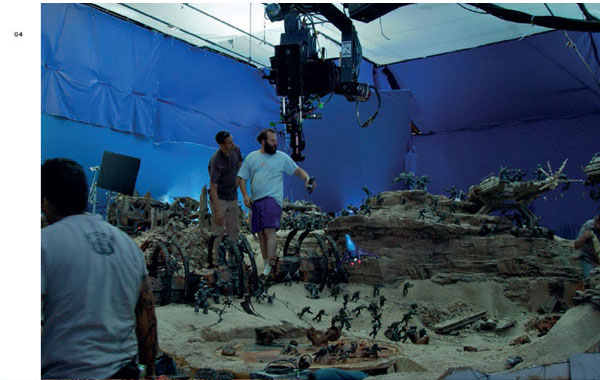

03-04 The team spent weeks carefully creating the giant diorama, before then shooting the Believe film and other films for the campaign within it.

‘We came up with this idea of honouring a hero, the way that humanity has always honoured heroes. Which is something that we figured everybody could relate to.’

The Halo games are centred on Master Chief, a cybernetically enhanced human soldier who is engaged in a battle against an alliance of alien races called the Covenant. The first two games in the series proved hugely successful, but with the third Microsoft wanted to reach a wider audience than simply the fans of the previous episodes. ‘It really has mass appeal,’ says Smith. ‘The product was built to do that – it was the first Halo game on Xbox 360, so the graphics and the game play and all that sort of stuff were meant to really dazzle people and appeal to a wider audience. But we knew we had a lot of work to do from a marketing standpoint to take it out to a broader set of consumers.’

The ad agency, TAG (now known as agencytwofifteen) in San Francisco identified three different target audiences that the marketing had to speak to. ‘We needed to talk to people that were within the Halo core; we needed to talk to entertainment enthusiasts who had never even bought a video game, much less owned an Xbox; and then there were people who were fence-sitters, between the two,’ say Scott Duchon and John Patroulis, creative directors on the project. ‘So when we briefed our teams on it they all laughed at us a little bit, that we were embarking on such a huge undertaking.’

They did come up with an idea, however, which was to step away from the specifics of the Halo story and focus the advertising on a more general notion of soldiers and warfare. ‘We came up with this idea of honouring a hero, the way that humanity has always honoured heroes,’ Duchon and Patroulis continue. ‘Which is something that we figured everybody could relate to. If you were inside the Halo core, you’d take that on and go “that’s cool, that’s what I’ve always liked about him”, and anybody outside of that would go “the fact that I missed [the first two games] is okay, because there’s something really compelling and emotionally resonating for me”.’

The creatives drew on classic heroic tales such as Beowulf and the legends of King Arthur as inspiration for building their own mythology around Master Chief. They proposed building a ‘virtual museum’, centred on a giant diorama that would depict battle scenes and war stories in a format that people could understand from having experienced similar historical exhibits in real museums. The diorama would be used across all the marketing for the Halo 3 game. The intention was to create a sophisticated film, set to classical music and featuring no game footage – all techniques far removed from typical computer games marketing.

TAG commissioned director Rupert Sanders to work on the project. ‘My treatment really focused on how to create the diorama and the story to be told within,’ he says. ‘My first decision was that it should be a real object, that could be exhibited in a museum. A handcrafted piece that used no digital effects and abided by the rules of a diorama, i.e. anything we saw in motion had to be held there as if viewed in a museum. We looked at a lot of modelmaking, mainly depicting World War II scenes and mostly from hobbyists. We also looked at museum dioramas and Jake & Dinos Chapman’s Hell. The challenge was to create emotional scenes and movement with frozen figures.’

‘I wrote a war story that told of a battle that had turned against the marines, and tried to capture the fear and horror of war,’ Sanders continues. ‘It started with a group of soldiers trapped in a bunker, moved out through streets where marines were being decimated, and then moved out across a polluted river where marines were caught in the mud while being fired upon by banshees from above. It then moved up to a heavily defended bridge and then to a mountain swarming with hundreds of enemies. The story finally climbed up this hill where a Christ-like Master Chief was held aloft by Chieftans – the battle looks lost, but then we see the primed grenade in his hand and he looks up to the camera as if to say “the battle is not lost, yet”.’

Xbox loved the idea and work began on the diorama, which grew beyond anybody’s initial expectations. ‘We had envisioned something that was the size of a room, then kept getting reports back from the teams building it, who were just pouring their hearts and souls into making this thing much bigger, and much grander, than frankly we were paying for,’ says Taylor Smith. ‘It was one of those things where you take a brand like Halo, which people are already interested in, and you put a really nice idea around it, get good people involved and it just keeps going and going to a bigger and more exciting place than you could even imagine. It wound up being the size of a giant warehouse – it was massive in scale. All the characters were handcrafted. Really amazing.’

Creating each individual soldier was a complex process, as Rupert Sanders recalls. ‘We decided to make 3D scans of actors and ourselves in various emotional states (I am a crying soldier, hiding behind his rifle). These were then outputted and painted and attached to bodies in pre-determined postures that were required for each scene. This was done by Alan Scott at Stan Winston Studios (now Legacy Effects), who created all the handpainted heads, as well as 500 marines and 1,500 enemy brutes and Chieftans.’

05 The diorama grew beyond everyone’s initial expectations: the final set was the size of a giant warehouse, and sections had to be built outside.

06 To give personality to the characters, the team made 3D scans of people’s faces in various emotional states, which were then painted onto the figures.

07 Each figure was individually designed and painted before being placed within the diorama.

08-09 Storyboards were used to map out the dramatic scenes that would appear in the final film.

10-14 The film saw the Halo games’ hero, Master Chief, and his soldiers pitched against an alliance of alien races called the Covenant. Every scene was carefully built by hand.

‘It was one of those things where you take a brand like Halo, which people are already interested in, and you put a really nice idea around it, get good people involved and it just keeps going and going to a bigger and more exciting place than you could even imagine.’

Sanders worked with New Deal Studios to create the sets for the action sequences. The diorama featured trenches and explosions, destruction and despair. In fact, the violence depicted was so great as to cause some concern among the creatives that the film would be banned. ‘Everyone had thrown themselves in and built this big, beautiful diorama, and we’re shooting it, and as the days are going by, it just became more and more apparent that we really had created this incredibly violent piece,’ say Duchon and Patroulis. ‘Which is what we all got excited about, but we had to make sure that this thing could air.’ In the end, the ad benefited by being a model, as using figurines allowed the team to show imagery that would have been banned in an ad that used real actors. There was also concern not to offend anyone, which was a particular worry regarding some extra web films made as part of the campaign, where veterans looked back on their days on the battlefield. ‘Microsoft as a client didn’t want to get anyone upset at them, and we certainly didn’t want to create a bad PR story for Xbox or Halo,’ say Duchon and Patroulis. ‘But we showed a lot of care and sensitivity. We were all amazed by the response from veterans, and from people who are serving in the military overseas. There were lots of comments on YouTube saying things like “this makes me feel proud of serving”. But we could have made this whole thing and someone could have said “nope, the way Iraq is right now, we’re not going to run this”.’

The finished campaign broke in a number of different stages. Before the main diorama film was released on TV and in cinemas, a number of web films were seeded online. A website was then launched when the main film aired, offering a flythrough of the diorama and more detail of the idea. In addition, the team made a making-of film, which rather than showing the making-of an ad campaign, remained within the fiction TAG and Xbox had created and showed the making-of a monument to war, as if the events shown in all the films were real. Initially there were plans to exhibit the diorama in various venues, but this proved prohibitively expensive. Sections were taken from it and displayed in retail spaces, however, and an exhibition of still photographs taken in the diorama were shown at the IMAX cinema in London as part of the campaign.

Xbox’s approach to advertising Halo 3 was risky, but the elegant films struck a chord with audiences, leading to Halo 3 becoming the fastest pre-selling game in history. The campaign also achieved the ambitions laid out by Microsoft at the start: the game made a cool $170 million in sales on the first day of its release, making it the biggest launch in entertainment history.

15-18 The film showed scenes that were filled with violence and despair, but due to being created using models, rather than actors, it escaped censorship.

19-25 Stills from the final Believe film.

‘We were all amazed by the response from veterans, and from people who are serving in the military overseas. There were lots of comments on YouTube saying things like “this makes me feel proud of serving”.’