Sony Bravia

Balls

Fallon

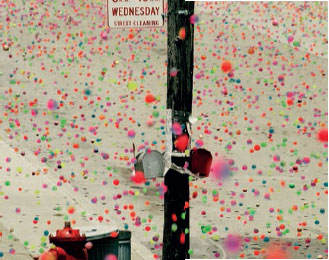

One of the most memorable commercials of the 2000s, Sony Balls is a simple proposition. Hundreds of thousands of coloured balls are launched down a hill in San Francisco to create a film that radiates joy, playfulness and a love of colour. In advertising terms though, the film is unusual. It was created to launch Sony’s Bravia high-definition television line in 2005, but the product is nowhere to be seen – instead, the audience is offered a feeling. They are invited to connect an emotion with the brand, rather than be wowed by the product’s technical capabilities. This strategy ultimately proved highly successful, although it required considerable persuasion by the ad agency, Fallon in London, and bravery by the client to exist at all.

‘We wanted to harness a point about colour, so it was important to not just show colour, but to feel colour as well.’

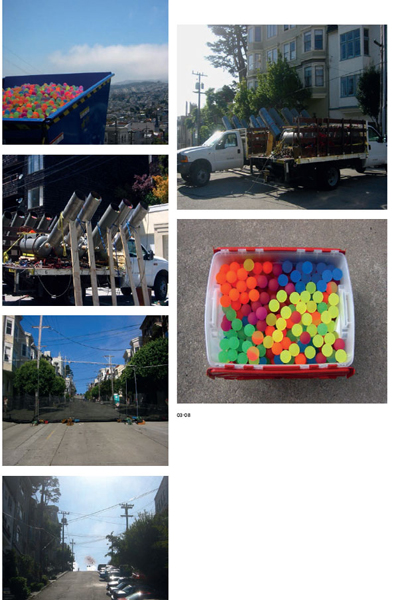

01-02 For the Sony Balls commercial, hundreds of thousands of coloured balls were thrown down the hilly streets of San Francisco. The aim of the ad was to emphasize the Sony Bravia television’s superior colour.

‘Even though it is a brilliant piece of advertising, it could be seen as an original and conceptual piece of art as well.’

The initial concept for the spot was born out of the endline that Sony had instructed should be used on all of its advertising: ‘Like No Other’. ‘It was a global edict,’ explains Laurence Green, then chairman of Fallon. ‘The great irony was “Like No Other” was written by Y&R in North America, imposed on everything globally that month, and then they lost the business about a month later. We were the first people to carry “Like No Other”; we said, we don’t really like that on its own, but let’s attach it to the specifics or premise or benefits of the Vaio, or the Walkman, or, in this case, Bravia – which was colour. So we knew the commercial was going to conclude with “Colour Like No Other”.’

Another early problem that the creative team identified was that they were trying to sell a new television to an audience via their old sets. This provoked the idea of the ad expressing an emotion, rather than technical prowess, as they would then have a piece of branding that would resonate beyond the specifics of where the ad was being viewed. ‘It’s a funny head-screwer,’ says Richard Flintham, then executive creative director at the agency, ‘you’re going to be demonstrating how good this is on a different television. We wanted to harness a point about colour, so it was important to not just show colour, but to feel colour as well. That was the big leap – that it would be nice if you really felt this. So we put that in the brief, and Juan [Cabral, creative at Fallon] came back with “let’s chuck some bouncy balls down a hill”.’

This was pretty much the idea the agency presented to Sony, who liked it but were uncertain, in part because of the proposal’s simplicity. ‘They were used to more words,’ says Flintham, ‘but no matter how you try… Juan and I sat there and tried to make it sound longer, but we really struggled to get to a quarter of a page.’

The budget required was also a worry, alongside a concern over the lack of product that would be on show in the film and the fact that it was focusing on just one quality of the television. In early feedback, the client proposed that the piece should showcase sound as well as colour. But Fallon held firm to the original idea, despite it being ‘bought and un-bought, pre-produced and un-pre-produced,’ according to Green. ‘There were moments where we had to say “honestly, this will be the best piece of work we’ve ever done, you have to do this”,’ continues Flintham. ‘From a script, there’s a lot of trust involved in that, a lot of money. It’s a big call.’

After many meetings the go-ahead was given and Fallon sought a director. Nicolai Fuglsig was chosen, and from the start he recognized the film’s potential to be something startlingly different from the average ad. ‘Even though it is a brilliant piece of advertising, it could be seen as an original and conceptual piece of art as well,’ he wrote in an early treatment. ‘There is no doubt that a very entertaining and colourful film like this could easily end up in galleries like Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art. I think it’s such a great idea that for the main spot we don’t focus on anything but the fantastical journey of the balls.’

Fuglsig was also adamant that the action in the ad be real, rather than a computer-generated concept, which chimed with the creatives’ ambitions too. ‘There is something so goddamn cool and honest about that,’ he wrote in the treatment. ‘From the whole shoot and PR point of view it’s so great that yes, we are in fact going to drop loads of colourful bouncing balls down some steep streets in a huge city. And I promise you that so much totally unexpected and surprising footage evolves when you actually do things in camera and for real.’

The team settled on hilly San Francisco as the ideal location for the shoot and then spent considerable time sourcing the right, and the most affordable, balls. Fuglsig was keen that the balls be small – ‘I feel it is really important that we stay far away from the Ronald McDonald playground-sized balls and even more important that we stay away from football-sized balls,’ he wrote at the time. A launching device was also required. ‘We saw projection devices, and different cannons, and lorry-mounted cannons, and building-mounted cannons… all this sort of stuff,’ says Flintham. Tests were done on virtually everything, before the shoot began.

‘I think Sony loved it not just because it worked, but because it elevated marketing and what advertising could do for their business.’

3-11 Photographs taken during the shoot for the Sony Balls commercial reveal the crude cannons that were initially used to launch the balls, and the large nets that were set up to try and catch them. Surprisingly little damage was caused during the shoot, although some untested ‘rogue balls’ did result in a few breakages.

When viewing the finished film, it is easy to imagine that the launching of the real balls would be spectacular, romantic even. In reality, it was quite shocking. ‘We thought it would be beautiful,’ says Flintham. ‘I took my little boy, Tom – he was five then – and thought it would be a lovely, beautiful thing for him to see. Then we were on a balcony, having been given helmets and some sort of riot shield, and they get released and you just hear the most deafening car alarms, and the odd window smashing.’

Surprisingly, despite the capacity for chaos, the shoot largely went to plan, aside from the impact of some ‘rogue balls’ that had been sourced at the last minute and missed the tests. ‘I think there was one story of someone who came home from holiday and found a perfect hole in his window and a bouncy ball on his floor,’ says Flintham. ‘But it’s America – it’s all been completely sorted out. There were giant nets and every drain’s been covered, there was nothing that could go wrong… apart from when those balls did start to break windows and we weren’t allowed to use cannons anymore. We had to drop them from skips, from big dumper trucks. This meant the balls went down before they went up, rather than up before they went down.’

In the finished film, the balls appear like coloured pixels, bouncing through space. The effect is startling, and emotional. Certain moments ground the scenes in reality though – a woman is shown watching the balls go by through a window, dustbins are knocked over, and, most notoriously, a frog is shown leaping from a drainpipe. This last touch was introduced by Fugslig. ‘That one jumped completely out of my head,’ he says. ‘We cut up a drainpipe, stuffed the fat frog in there, and gently looped five colourful balls into the pipe. We’d already rigged a little lid with some fishing wire on it that we yanked right before impact.’

The atmosphere of the final ad is created in part by its music, which is a gentle, folksy track written by Swedish musicians The Knife, and performed by José González. It was initially suggested by Flintham. ‘There was a theory that we might use something like that, because it felt nice, it was honest, the brand was being warm,’ he says. When they played it alongside the rushes, it worked perfectly, and the music in fact led to the ad achieving a wider showcase than could have first been imagined. González bought out a single of it, and appeared on UK music television show Top of the Pops with the ad playing behind him. By serendipity, the music ended up fulfilling Sony’s original desire for the ad to contain an emphasis on sound too. ‘You’d suddenly hear conversations about the way that you can hear the strings,’ says Flintham, ‘the little moments when José touches the string, brushes the string. That ticked the sound brief – and of course we meant that as well.…’

‘I think there was one story of someone who came home from holiday and found a perfect hole in his window and a bouncy ball on his floor.’

Sony Balls as an individual ad is immensely striking, but the making of it also unexpectedly signalled a sea change in the way that advertising is shared with the public. At the time, advertising was still an extraordinarily secretive world – the suggestion that an idea for a launch campaign could be leaked in advance was catastrophic. ‘The rules of campaigns, and especially product launches, were that you go away and you privately shoot something, plan something, plot something, and then when it’s all perfectly polished and honed, you present it to your internal people, then you present it to the trade, then, on a certain day, it appears. People see it for the first time on the air date,’ explains Green. ‘It seems kind of sweet now that that’s how it used to work.’ By throwing 250,000 balls down a hill though, it was difficult to keep the idea under wraps, and the agency discovered that photographs and videos of the balls were popping up all over the internet even before the shoot was over.

The news was initially terrifying, although Flintham now describes it as ‘the day we woke up as an agency,’ as they began to realize that such unsolicited enthusiasm for the enterprise could only be a good thing. The leaked imagery also served as a teaser for the final film, which of course was quite different. ‘What they didn’t know is that what was coming is slow motion, and they don’t know the music,’ says Flintham. ‘Literally we had wave after wave of news.’ The rest of the ad industry watched this occur, and realized its power. Controlled leaks prior to an ad’s release and making-of films have now become standard in the industry, with agencies these days longing for their audiences to be interested enough to share this information with their friends.

12-16 Stills from the final commercial. The visuals were set to José Gonzáelez’s folksy cover version of The Knife track ‘Heartbeats’, which gave the commercial a warm, almost hypnotic feel.

By the time that Sony Balls was finished, both the agency and the client knew that they had something astonishing, so they aired it with great confidence – first in a two-and-a-half-minute version that played out in the UK in the middle of a Chelsea versus Manchester United football match, a sporting event that guaranteed a huge audience.

Fallon had set a tone for the brand that would continue in its advertising for many years. ‘I think Sony loved it not just because it worked,’ says Green, ‘but because it elevated marketing and what advertising could do for their business. It elevated it back to a level it had been maybe 10 years previously, maybe 20 years previously. For big projects, it wrote a new model for how Sony would go about marketing stuff.’