26/

The History of Gaming; The Future of Gaming

Johnny Hardstaff

Traditionally, an advertising campaign is developed in a fairly formulaic fashion. A client will brief its agency, the agency will devise a campaign, and – for TV commercials at least – a director will be commissioned to bring the idea to life in film. Occasionally, however, a project will follow a less ordinary path, as is the case with two brand films that were created for Sony PlayStation back in 2000–01. The films are unusual firstly in their content: rather than advertising a specific aspect of PlayStation to customers, they convey a general message about gaming itself, and its significance to our lives. The first film depicts gaming’s past, while the second is a meditation on what gaming’s future may look like.

01 Director Johnny Hardstaff’s first film for Sony is a nostalgic look at gaming’s past, with imagery from old computer games set to a soundtrack of Minnie Ripperton’s soul track Les Fleurs. Stills from the finished film are shown here, while two pages from Hardstaff’s sketchbooks for the film are overleaf.

The development of the films was unconventional too, for rather than being made to a brief, they were conceived entirely by director Johnny Hardstaff, who, upon finishing his first short film, decided to pitch it directly to a client. He chose Sony, who immediately recognized the potential of his work. This first film had developed out of a combination of creative experimentation and tenacity. Having studied graphic design at Central St Martins College of Art and Design in London, Hardstaff was determined not to enter a dead-end design job on graduation. Instead, he worked in a variety of places – including a mortuary and at Billingsgate Fish Market – and toiled away on his own projects at night. ‘I’d been keeping sketchbooks and amassing all this information,’ he says of this time. ‘Then the sketchbooks got to a point where I started to do drawings and develop these graphic freeforms. I thought it would be really nice to make them move. There was no rhyme or reason. I thought I’d build a narrative out of these sketches, put it all together and show people.’

Hardstaff chose the laborious process of using Photoshop to make his first moving-image piece. ‘I didn’t have any training in anything, and I’d taught myself to use Photoshop,’ he explains. ‘It was the worst way of working, but I wasn’t even aware that there was a program called After Effects. So I made it in Photoshop, which means you save a frame and go on to the next, it’s like cell animation.’ After months of work, Hardstaff took all the frames to Lux, an arts centre in London, where a technician put them together with the music that Hardstaff had chosen. ‘I saw the film, which was kind of emotional – I cried,’ he says.

With the encouragement of those who’d seen it, Hardstaff decided to approach Sony PlayStation with the film. It was a successful meeting. The film featured a number of game motifs, and was set to the nostalgic but joyous tones of Minnie Ripperton’s song Les Fleurs; Sony saw that it could become a homage to computer gaming’s past. ‘They saw some chronology within it, and said “could you modify it and call it The History of Gaming?”,’ says Hardstaff. ‘They felt they could use it for some kind of subversive purpose.’

To many young directors, such an opportunity might seem like a dream come true, yet Hardstaff was uncomfortable about the company’s intentions from the outset. ‘In the meeting I took such a dislike to them and this marketing nonsense,’ he admits. ‘I took a dislike to the idea that their agenda was creeping so heavily into something I was making.’ But alongside this disquiet, Hardstaff was aware of the potential of the connection. ‘Already they were talking about another one,’ he says. ‘I thought, I’ll do this, but I wonder what we can do on the next one..’

Hardstaff modified the film and Sony was delighted with it, releasing it with the PlayStation 2 console when it launched, and showing it at film festivals and events. Hardstaff gained attention as a result and signed to RSA Films for representation. On the back of the success, Sony was indeed keen for another film from him, this time on the theme of The Future of Gaming. There was little budget on offer, however, so Sony came to an unusual arrangement with Hardstaff and RSA: they agreed to sign a contract that gave the director full ownership of the film, meaning he would be allowed to show it wherever he liked. This gave Hardstaff just the freedom he’d been after, along with ample opportunity for mischief.

Hardstaff set about looking for a narrative that would prove provocative. ‘I heard about a brilliant conference call that had gone on in [Sony’s] office, because I’d got to know one of the secretaries there,’ Hardstaff says. The conference call related to a UK marketing campaign for the brand that had gone horribly wrong. ‘Legend has it there was this amazing call between Mr PlayStation in Japan and the PlayStation marketing manager in the UK, where he just ripped the life out of them,’ he continues. ‘I thought that was too tasty to miss, so I thought I’d use that as the basis for this film. I thought that would really annoy them.’

‘It was exciting because I could see already that the commissioning opportunities in the UK within advertising and music videos were challenged,’ he continues. ‘It was really tricky to make anything that one wanted to make.. I felt that the commissioning opportunities were such that one needed to try to explode a hole in it, or explode a hole for yourself.’ I was feeling spunky enough to just have an agenda and put it out there, to see what people would say. I wasn’t clamouring to work in advertising.’ And if you annoy a huge corporation, Hardstaff believes, ‘they’re so big that they don’t care, they’ll just come back one day.’

‘It was really tricky to make anything that one wanted to make.… I felt that the commissioning opportunities were such that one needed to try to explode a hole in it, or explode a hole for yourself.’

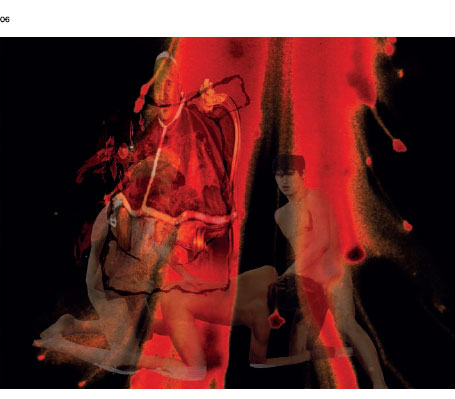

The second film that Hardstaff created for Sony PlayStation is dark in tone, featuring shocking imagery overlaid with a spoof of the conference call. It is stylistically utterly in opposition to the feel-good atmosphere of the first short. ‘I thought we’d been really clever in getting a corporation to pay for essentially an anti-corporate piece of work,’ says Hardstaff now. ‘We went in there and played it to them – and there were cakes and stuff, it was a really nice setting – and basically they never spoke to us again. There was absolute silence. People walked out and we were left with a film that they just wouldn’t touch.’

‘We’d kept the copyright though, so we could go and put it wherever we wanted,’ he continues. ‘So we did – we put it everywhere we possibly could. The film festivals just loved it, went mad for it, showing it globally. It’s gone everywhere – even Tate Modern.’

Such a viral response to a film prior to the launch of websites such as YouTube or Vimeo is impressive. Hardstaff’s film was an early precursor, albeit a risqué one, to the short films that brands have begun to sponsor in recent years, which are intended to be viewed and shared online. Yet his film was spreading without the benefits offered by the internet. Despite this, looking back on the experience, he is not as happy with the outcome as might be expected. ‘I knew I’d pulled some punches with it, in a way,’ he says; ‘because as much as it’s an anticorporate piece, it kind of aggrandises PlayStation as well. I had a very negative view of their product. I never play, and have never really played computer games, because I can’t imagine wasting that amount of time. For kids it’s brilliant, but I really resent what they’re doing to people. But I pulled my punches.’

02-07 Hardstaff’s second film – which had the future of gaming as its theme – was deliberately a much darker affair. Stills from the finished film are shown here, alongside a detail from one of Hardstaff’s sketchbooks (05), within which he collated imagery and ideas related to the film.

‘It made them look fabulous. People couldn’t believe this had been made for PlayStation. Their caveat, their get-out-of-jail card was that they had nothing to do with it. They didn’t endorse it, but they were happy to leave their logo on it.’

Even more frustratingly, Hardstaff now feels that, despite his intentions, he played directly into Sony’s hands, creating a film that in fact boosted the brand rather than humiliating it. Though the corporation couldn’t be seen to have commissioned something so provocative, they undoubtedly benefited from its success.

‘It made them look fabulous,’ Hardstaff concludes. ‘People couldn’t believe this had been made for PlayStation. Their caveat, their get-out-of-jail card was that they had nothing to do with it. They didn’t endorse it, but they were happy to leave their logo on it. They’re big enough, they could have crushed the whole thing if they’d wanted. They could lock you down into years of legal dispute. They didn’t. They let it go everywhere.’

Both The History of Gaming and The Future of Gaming still enjoy regular attention via the internet more than ten years after their first release. And despite his mixed feelings about them now, the films kickstarted a fruitful career for Hardstaff, who has since created films and music videos for a number of artists and brands. Somewhat ironically, these clients still include Sony, who, as he prophesized, did indeed eventually come back for more.

08-14 Pages from one of Hardstaff’s sketchbooks for The Future of Gaming film are shown, overlaid with stills from the finished film. In the end, The Future of Gaming proved too risqué for Sony to officially endorse, although as Hardstaff owned the rights, it appeared in film festivals around the world regardless.