Chapter 2

Phase I: Develop the Organizational Portfolio

The best plans of mice and men are only as good as the way they’re implemented.

H. James Harrington

The sated appetite spurns honey, but to a ravenous appetite even the bitter is sweet.

Proverbs 27:7

Introduction

The object of the activities that make up this chapter is to develop the Organizational Portfolio by evaluating the set of proposed business cases (each proposed business case was already aligned with a value proposition) to determine which of them will be selected as a project or program to be approved (or not) and included in the portfolio, either to be launched for the first time or, if one has already been established, to continue in the next time period.

Before proceeding any farther, let’s understand three of the fundamental terms we will be using throughout the remainder of the book.

- 1. Portfolio: A centralized collection of independent projects or programs that are grouped together to facilitate their prioritization, effective management, and resource optimization in order to meet strategic organizational objectives.

- 2. Value Proposition: A document based on a review and an analysis of the benefits, costs, and value that an organization or an individual project or program can deliver to its internal/external customers, prospective customers, and other constituent groups within and outside the organization. It is also a positioning of value, where Value = Benefits – Cost (where cost includes risk).

- 3. Business Case: This is an evaluation of the potential impact a problem or opportunity has on the organization to determine if it is worthwhile investing the resources to correct the problem or take advantage of the opportunity. An example of the results of the business case analysis of the software upgrade could be that it would improve the software’s performance as stated in the value proposition, but (a) it would decrease overall customer satisfaction by an estimated three percentage points, (b) require 5 percent more task processing time, and (c) reduce system maintenance costs only $800 a year. As a result, the business case did not recommend including the project in the portfolio of active programs. Often the business case is prepared by an independent group, thereby, giving a fresh, unbiased analysis of the benefits and costs related to completing the project or program.

Developing the Organizational Portfolio: A Typical Scenario

The term business case is frequently used as part of the annual budget cycle for the organization. To help you understand the complexity of defining which business cases are included in the Organizational Portfolio, we present the following organizational structure for a “typical” manufacturing organization (Figure 2.1).

The organization is in the middle of its annual budgeting cycle. Estimates on the resources required to support the previously approved products, programs, and projects have already been submitted and they are running about 18 percent over projected budgets already. In addition, each function has submitted new business cases (see the series: Little Big Book—Making the Case for Change: Using Effective Business Cases to Minimize Project and Innovation Failures (CRC Press, 2014)) that they would like to initiate since they would (or should) fulfill one of the identified value propositions (see the series: Little Big Book—Maximizing Value Propositions to Increase Project Success Rates (CRC Press, 2014)). As a result, a stack of approximately 125 unranked business cases are sitting on the CEO’s desk awaiting approval. A quick review of the business cases indicates that it would require 35 percent more available resources to implement all of these proposed improvements.

Now, among them is a set of these proposed business cases from Development Engineering, all of which would make excellent technical research papers, but some of them also are directly aligned with the organization’s mission and vision statement.

There is another set from Product Engineering for new products that have potential to generate additional revenue for the company. However, the CEO fears that only some of these proposals will actually be profitable and the others will be “money losers” for the organization.

Industrial Engineering wants to automate the DASD (direct access storage device) line, but Production Control has a proposal in to subcontract and offshore that same secondary storage device line to China.

Marketing and Sales wants to implement a new, enterprise-wide Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system to find, attract, and win new clients; nurture and retain those the company already has; entice former clients to return; and reduce the costs of marketing and client services. However, this Marketing and Sales initiative would require heavy investment in Information Technology resources that may be better utilized on other undertakings.

Finance and Accounting wants to convert to an automated activity-based costing system to reduce the cost of order processing activities.

Quality has proposed redesigning the order processing process.

Finally, it seems like just about everyone has some work that they want the Information Technology Department to do for them to make their respective jobs easier. Besides, the CIO (chief information officer) wants to upgrade the enterprise to the cloud version of latest office productivity software suite.

Some of these business cases indicate that there are no additional resources required to implement them, but the CEO questions if these resources would be better utilized doing something else that would create more value added to the organization. The CEO realizes that if all these initiatives were approved, the organization wouldn’t have enough resources to manufacture the present product lines that are paying everyone’s salaries.

Because the organization needs to reduce costs and create maximum value with these resources, some of the projects that are presently underway, but are underperforming, may be of less value than the ones that are currently being proposed. “If so,” he wonders, “which current project(s) should be dropped to free up resources to implement the more profitable new projects or programs?” Based on past experience, the CEO knows that some functions tend to underestimate the resources required for a project and overestimate the value that the project will create. Other functions do just the opposite by overestimating the resources required and underestimating the project’s value to the organization.

Because almost all projects take longer to implement and cost a great deal more than estimated, a given business case based on a particular value proposition may sound very straightforward and optimistic, but then, along come the “add-ons” and systems interfaces. It’s not unusual to find that, once a project has been approved for, say, $1 million, halfway through the schedule, the CEO is informed that it’s going to fail unless an additional $100,000 is invested in it. So, he is pretty much obligated to spend the additional resources to salvage the project (the classic “sunk cost” dilemma). In fact, this seems to be more the rule than the exception in recent years. As a result, budget overruns and schedule delays are prevalent on most projects.

Returning to our “typical” Organizational Portfolio scenario, there are nine questions that the CEO should ask at this point in the portfolio development process:

- 1. To whom should I give this stack of business case proposals who will give an unbiased evaluation of which ones should be included in the organization’s active portfolio of projects and programs?

- 2. How should these initiatives be prioritized?

- 3. How will the stakeholders react to the implementation of the approved initiatives?

- 4. How many resources are available to support the newly proposed initiatives?

- 5. Do we have the right skills to implement the approved initiatives and, if not, how do we find them?

- 6. Who is going to be managing each of the approved initiatives?

- 7. What is the schedule for implementing each of them and how do they relate to the work activities that are already going on within the organization?

- 8. What are the interrelationships and interdependencies between the approved initiatives?

- 9. Which initiatives need to be grouped into a portfolio or group of portfolios and which ones can be handled as a part of the functional department’s normal activities?

In this chapter, we provide answers to these nine questions the CEO should be asking when focusing on the development initiatives (projects and programs).

Thirteen Fundamental Terms

Before proceeding, let’s clarify 13 more fundamental terms that are used in the remainder of this book:

- 1. Mission Statement: The stated reason for the existence of the organization. It is usually prepared by the CEO and key members of the Executive Team and succinctly states what they will achieve or accomplish. It is typically changed only when the organization decides to pursue a completely new market.

- 2. Policy: A principle or rule to guide decisions and achieve rational outcomes; an intent to govern that is implemented as a procedure. Policies are generally adopted by the Board of Directors or senior governance body within an organization, whereas, procedures are developed and adopted by senior and middle managers. Policies can assist in both subjective and objective decision making.

- 3. Vision Statement: It provides a view of the future desired state or condition of an organization. (A vision should stretch the organization to become the best that it can be.) The vision statement provides an effective tool to help develop objectives.

- 4. Value: The basic beliefs or principles upon which the organization is founded and which make up its organizational culture. They are prepared by top management and are rarely changed because they must be statements that the stakeholders hold and depend on as being sacred to the organization.

- 5. Strategy: It defines the way the mission will be accomplished. Using a well-defined strategy provides management with a thought pattern that helps them better utilize equipment and direct resources toward achieving specific goals; e.g., “The company will identify new customer markets within the United States and concentrate on expanding markets in the Pacific Rim countries.”

- 6. Critical Success Factors: These are the key things that the organization must do extremely well to overcome today’s problems and the roadblocks to meeting the vision statements.

- 7. Business Objectives: Business objectives are used to define what the organization wishes to accomplish, often over the next 5 to 10 years.

- 8. Organizational Goals: They document the desired, quantified, and measurable results that the organization wants to accomplish in a set period of time to support its business objectives; e.g., increase sales at a minimum rate of 12 percent per year for the next 10 years with an overall average annual growth rate of 13 percent. Goals should be specific rather than general so that there is no ambiguity.

- 9. Strategic Business Plan: This plan focuses on what the organization is going to do to grow its market share. It is designed to answer the questions: What do we do? And how can we beat the competition? It is directed at the product.

- 10. Organizational Master Plan: The combination and alignment of an organization’s Business Plan, Strategic Business Plan, Combined Performance Acceleration Management (PAM) Plan, and Annual Operating Plan.

- 11. Business Plan: A formal statement of a set of business goals, the reason they are believed to be obtainable, and the plan for reaching these goals. It also contains background information about the organization and/or services that the organization provides as viewed by the outside world.

- 12. Initiating Sponsor: Individual/group that has the power to initiate and legitimize the change for all of the affected individuals.

- 13. Sustaining Sponsor: The individual/group that has the political, logistical, and economic proximity to the individuals affected by a new project/activity.

Activities for Phase I

Phase I (Develop the Organizational Portfolio) is made up of the following seven activities:

Activity #1: Assign an individual and/or team (Portfolio Development leader) to set up and manage the development of the Organizational Portfolio.

Activity #2: Classify the business cases using a quantitative, qualitative, or blended model based on each one’s potential value.

Activity #3: Prioritize the projects and programs based on the resources available.

Activity #4: Select projects and programs for the portfolio(s) and assign a Portfolio leader to oversee it/them.

Activity #5: Identify a sponsor and a project manager for each project and program.

Activity #6: Define high-level milestones and a budget for each project and program.

Activity #7: Obtain executive approval for each project and program including its high-level milestones and budget.

Below, we define each activity, in sequence, and identify each one’s respective inputs, activities, and outputs.

Activity #1: Assign an Individual and/or Team (Portfolio Development Leader) to Set Up and Manage the Development of the Organizational Portfolio

For a small organization (10 or fewer combined projects and programs,), this “entity” could be an individual with the right leadership credentials and characteristics. For a medium-sized organization (10–25 combined projects and programs,), this could be either one or two individuals or a department led by an individual with the right leadership credentials and characteristics. For a large organization (more than 25 combined projects and programs), this should be a department led by an individual with the right leadership credentials to be able to handle the demands adequately. Usually this assignment is given to one of the established functions to coordinate like Finance, Project Management, or Project Engineering.

Here are the inputs, activities, and outputs for Activity #1 to recruit and assign the appropriate entity or entities to develop the Organizational Portfolio(s):

- Input(s):

- The organization’s mission statement and strategic plan

- OPM mission statement from the Executive Team

- Portfolio Development leader credentials and characteristics

- Portfolio Development Team role and responsibilities (if appropriate)

- Portfolio Development Team member credentials and characteristics (if appropriate)

- Activities:

- Talent recruitment and acquisition

- Candidate interviewing for the Portfolio Development leader

- Human Resource selection for the Portfolio Development leader assignment

- Interviewing and selection of individuals for the Portfolio Development Team assignment

- Output(s):

- A set of criteria aligned to the organization’s mission to classify and rank the business cases

- A Portfolio Development leader is selected and on board

- Portfolio Development Team member(s) are selected and on board (if appropriate)

Inputs

- The organization’s mission statement and its strategic plan

These two are key inputs into evaluating and prioritizing projects/programs. All of the approved projects and programs should directly support the organization’s mission statement that defines the kind of business the organization was formed to be involved in. They also should be directly in line with the organization’s strategic plan. The strategic plan provides guidance to the total organization related to how the Executive Team and the Board of Directors desire the organization to evolve over the near-term future. Usually this is a 5- to 10-year period. Projects and programs that are not aligned with the organization’s mission statement should not be considered for implementation unless there is a change to the mission statement. Projects and programs that are in line with or support the organization’s mission statement, but are not directly in line with the organization’s strategic plan, can be considered candidates to become part of the organization’s portfolio of active projects/programs. However, these projects and programs have a far lower chance of being implemented than those that directly support the organization’s strategic plan.

- An OPM mission statement from the Executive Team

Every Portfolio Development leader and his/her team must have a clear direction for themselves coming from a mission statement issued by the CEO or, even better, by the organization’s entire Executive Team. It should be strategic, “action-oriented,” and succinct. The OPM mission statement should directly support the mission statement for the organization. Here are several examples from our experience of successful organization’s mission statements:

- Example #1 (Fortune 500, For-Profit, Public Business Organization): “A relentless drive to invent things that matter: innovations that build, power, move, and help cure the world. We make things that very few in the world can, but that everyone needs. This is a source of pride. To our employees and customers, it defines (us).”

- Example #2 (National, Nonprofit Charitable Organization): “Provide compassionate care to those in need. Our network of generous donors, volunteers, and employees share a mission of preventing and relieving suffering, here at home and around the world.”

- Example #3 (Federal Government Organization): “Protect the public health in the United States by ensuring the safety, effectiveness, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices; ensuring the safety of foods, cosmetics, and radiation-emitting products; and regulating tobacco products.”

- Example #4 (Local, Nonprofit Charitable Organization): “Work in partnership with pastors and community leaders of (the metropolitan area) by providing them with tools and resources to strengthen their capacities to address pain and poverty.”

- Example #5 (Global Nongovernmental Organization): “Build a better world by strengthening and improving the (parent organization) through the engagement of people who share a global mindset and support international cooperation–global citizens.”

- Example #6 (Medium-Sized, For-Profit, Business Organization): “Provide people around the world with all the good things milk has to offer, with products that play an important role in people’s nutrition and well-being.”

In the context of these six examples, the following is a typical mission statement for an Portfolio Development Team: “Do a fair and unbiased review of the proposed and presently active projects/programs to define the ones that will have the biggest impact upon the organization’s performance and reputation considering the resources that are available and the long- and short-range impact these proposed projects/programs will have on the organization.”

Note

The purpose of the Portfolio Development Team is not to recommend the acceptance of a project or program but to ensure that only those projects or programs that have a high potential of being successfully implemented and resulting in the maximum benefits to the organization are recommended to be included in the organization’s active projects or programs.

- Portfolio Development leader credentials and characteristics

The Portfolio Development leader must be a very special, strategically focused individual and should possess the following credentials:

- Is highly respected internally throughout the organization.

- Is an experienced “organizational change agent” or “facilitator of organizational change.”

- Is a strategic thinker with systems analysis or systems engineering experience.

- Must have no preconceived biases and/or prejudice.

- Must have the integrity to recommend rejection of popular projects and projects sponsored and/or suggested by high-level executives.

- Must value the time and skills of other personnel.

- Must be able to meet commitments that he/she makes.

- Must be creative in his/her approach to collecting data and analyzing the value a project/program will have

- Is proactive and preventive as an effective problem identifier, but can be an effective problem solver, when necessary, as well.

Additional traits to look for in selecting this Portfolio Development leader include:

- Understands the organization’s strategy

- Trusted leader

- Self-starter

- Good listener

- Excellent communicator

- Politically savvy

- Has a detailed knowledge of the organization’s business

- Understands processes and process improvement

- Customer-focused

- Passionate

- Motivator

- An excellent planner

- Excellent negotiation skills

Most important of all, this individual must serve as the “single point-of-contact” for the Executive Team, take ownership for the development of the Organizational Portfolio, and be able to either execute, or delegate the execution of, the remaining six activities in Phase I. In most organizations, this individual will either come from the Project Management Office (if the organization has one), Human Relations, or Finance.

- Portfolio Development Team role and responsibilities

If the organization has 10 or more projects, programs, and portfolios combined, the Portfolio Development leader will have to recruit and select one or more Portfolio Development Team members to assist her/him.

As an integrated group, the Portfolio Development Team should be comprised of individuals who will work together in support of the Portfolio Development leader to maximize the portfolio’s value to the organization, such that each project or program, which they recommend that the organization invest in, produces more value than any other way the resources could be invested. The typical Portfolio Development Team would be made up of individuals from all of the key organizations involved in the portfolio of projects and programs. Typically, it would be made up of representatives from R&D, the Project Management Office, Marketing and Sales, Finance, Human Relations, and Manufacturing Engineering. Like all teams, in order to be successful, it will need to go through the five stages of team development: forming, storming, norming, performing, and transforming.3 Unfortunately, this takes time.

The Portfolio Development Team’s role is to share ownership with the Portfolio Development leader for the development of the Organizational Portfolio by executing the remaining six activities presented in this chapter.

The Portfolio Development Team’s responsibilities will be determined by the Portfolio Development leader based on the unique demands of the organization’s culture and the portfolio itself. (See the next input below.)

- Portfolio Development Team member credentials and characteristics

Portfolio Development Team members should possess many of the same characteristics as the Portfolio Development leader, but not the same amount of experience. They should possess as many as possible of the following credentials:

- Is respected by the departments submitting business cases for inclusion in the portfolio.

- Has the potential to become an “organizational change agent” or “facilitator of organizational change.”

- Is a “systems thinker” with some systems experience.

- Must not be self-serving.

- Is proactive and preventive as an effective problem identifier, but can be an effective problem solver, when necessary, as well.

Additional traits to look for in selecting Portfolio Development Team members include:

- Willing to learn about the organization’s strategy and its strategic processes

- Trusted worker

- Self-starter

- Good listener

- Good communication skills

- Politically savvy and has leadership potential

- Has a detailed knowledge of the organization

- Coachable

- Customer-focused

- Energetic

- A capable planner and “toolsmith”

- Has a track record of being a successful project team member

- Excellent negotiation skills

- Must value the time and skills of other personnel

- Must be able to meet commitments that he/she makes

- Must be creative in his/her approach to collecting data and analyzing the value a project/program will have

- Has the ability to set aside personal interests for the good of the total organization

- Makes decisions based upon fact, not upon hearsay

Most important of all, these individuals must be willing to take shared ownership for the development of the Organizational Portfolio, and be able to support the Portfolio Development leader in carrying out the remaining six activities in Phase I.

Activities

- Talent recruitment and acquisition

This is the practice of searching for the best potential candidates for the Portfolio Development leader. The Executive Team should have this responsibility as this individual needs to be well known and respected by every individual on the Executive Team. Typically, this is done at an Executive Team meeting where a list of potential candidates is developed and the positive and negative traits of each are discussed. Based on this discussion, the Executive Team should select the Portfolio Development leader.

Because the members of the Portfolio Development Team have to possess special skills, it is best to delegate recruitment to the Human Resources Department and talent recruitment professionals to identify potential candidates who are then interviewed by the Portfolio Development leader.

- Candidate interviewing for the Portfolio Development leader assignment

This is the practice of determining, amongst the top potential candidates for a given Portfolio Development leader position, which one best matches the position’s requirements. This can be handled either via a telephone or face-to-face conversation, or both.

Even though this, too, is a specialty that is best led by the Human Resources and talent recruitment professionals, the CEO and/or COO need to be active participants in these meetings as they have a much better understanding of the difficulties that the individual candidates will face in preparing and managing the portfolio of projects. Organizations that have a Project Management Office will often give this assignment to the manager of the Project Management Office.

- Human Resource selection for the Portfolio Development leader assignment

This is the practice of choosing the final candidate for the position and preparing to make the final offer. Even though the final offer is usually presented to the candidate by the Human Resource representative, the final selection of the candidate is the responsibility of the CEO or COO, taking into consideration any recommendations that are made by the Human Resource Department representative.

- Interviewing and selection of individuals for the Portfolio Development Team assignment

The procedures for interviewing and selecting individuals to serve on the Portfolio Development Team are handled similar to the procedures used to interview and select the Portfolio Development leader, with the exception that the Portfolio Development leader is added to the individuals that do the interviewing and selection of the candidates for the Portfolio Development Team.

Because the team member’s assignment is usually a temporary short-term assignment (three to four weeks), candidates are usually selected from the internal operations based on their previous experience and knowledge of how the total organization functions. Typically, a number of the team members will be project managers who have already experienced managing projects/portfolios within the organization. It is good practice to have one member of this team hired from an outside source in order to give a nonprejudicial opinion related to which potential opportunities are recommended for implementation. This is often looked at as an additional unnecessary expense, but in the long run it is an excellent investment because it minimizes the risk of projects being selected based on internal politics rather than real value added to the organization.

Outputs

- A set of criteria aligned to the organization’s mission to classify and rank the business cases

Every Portfolio Development leader and his/her team must have a solid set of criteria that are aligned to the organization’s mission identified as the first input for this activity to use as a “sounding board” for ranking the proposed business cases. (Note: Since this is also an input for Activity #2, it is covered in more detail below.)

- Portfolio Development leader selected and on board

This is the practice of making the final offer to the candidate selected for the position, gaining acceptance of it, and ensuring that the newly hired (or transferred) person reports to his or her assigned manager.

Even though this, too, is a specialty that is best led by the Human Resources professionals, the CEO and/or his/her delegate(s) are often active participants in producing this output.

Once the individual is assigned as the Portfolio Development leader, he/she will review the requirements of the job and then he/she will jointly establish a detailed list of tasks and a timetable that is required to complete Activities #2 through #7 of Phase I.

- Portfolio Development Team member(s) are selected and on board (if appropriate)

See the description for Portfolio Development leader selected and on board output above.

Activity #2: Classify the Business Cases Using a Qualitative, Quantitative, or Blended Model Based on the Potential Value

Once the Portfolio Development leader (and his/her team, if appropriate) has been selected, he/she must drive the completion of the remaining activities in Phase I in an objective and professional fashion using a set of agreed-upon classification criteria.

Here are the inputs, activities, and outputs for Activity #2:

- Input(s):

- Portfolio Development leader

- Portfolio Development Team members (if appropriate)

- The business cases (proposed projects) to be classified

- Activities:

- Business case validation

- Document performance and project resource requirements for each project/program

- Business cases that do not require additional resources

- Select and use a set of criteria aligned to the organization’s mission to classify and rank the business cases

- Determine which classification model to use: qualitative, quantitative, or blended

- Output(s):

- An executive committee review and approved ranked-ordered list of projects and programs based on their potential value to the organization

Inputs

- Portfolio Development leader

- Portfolio Development Team members (if appropriate)

- The business cases to be classified

As part of a typical business cycle, each function should have submitted a set of business cases that they would like to start during the next business cycle. (Note: For details, see the two books mentioned above—Value Proposition Development and Business Case Development—in this Little Big Book series). On some occasions, the functional units submit project/program business cases for inclusion in the active approved activities within the organization between budget cycles. In these cases, the Portfolio Development Team handles them as a special case. These situations are discouraged, but in today’s organization with a very fast-changing environment it is practically impossible to eliminate these special evaluation cases and still have the organization function effectively.

Based on our personal experiences during a budget cycle, a number of improvement opportunities are identified that have not gone through the Value Proposition Development stage or the Business Case Development stage either. Often it is not practical to ignore these improvement opportunities and as a result the Portfolio Development leader will need to work with the individual functional area that is recommending or “nominating” these improvement opportunities to, at a minimum, prepare the data that are required for a business case so that the improvement opportunity can be fairly considered along with the other business cases. Often these last-minute improvement opportunities actually turn out to be “pet projects” sponsored by key executives within the organization and ignoring these key inputs could be politically “sensitive” and detract from the organization’s potential performance. Unfortunately, these improvement opportunities have a tendency to increase the length of the budgeting cycle and, as a result, should be discouraged whenever possible.

The Portfolio Development leader and his/her Portfolio Development Team will focus their attention on classifying and ranking these business cases to develop the prioritized list of potential projects that will be considered to make up the approved portfolio.

Activities

- Business case validation

The Portfolio Development leader should review each proposed project/program to ensure its business case is well-developed and includes practical and realistic estimates related to its goals, performance objectives, timing, and resource requirements. At a very minimum, realistic goals, performance objectives, timing, and resource requirements must be documented or the project/program will not be considered by the Portfolio Development Team for being included as an active project within the organization.

- Document performance and project resource requirements for each project/program

We find that while the Portfolio Development Team is reviewing the individual business cases/value propositions, this is an excellent time to prepare a list of all the projects being evaluated and record what the projected impact is on the organization’s performance and the resource consumption that is recorded in the business case or value proposition. We also suggest you record estimated implementation time and any risks that the group that prepared the business case defined as impacting the project/program. This provides an effective bird’s eye view of all of the proposed projects/programs being evaluated.

- Business cases that do not require additional resources

Many of the business cases that are completed do not require additional resources for their implementation. Many of the identified improvement opportunities can be implemented within the normal activities that go on within the function and already in the approved budget; e.g., product engineering could have resources already budgeted to correct problems or make small changes to a current product. This would include activities like redesigning a part that is presently a steel machine part and replacing it with a plastic molded part. Another example would be when an operator suggested a different inexpensive tool be purchased to help them assemble a part and there’s already money in the budget for miscellaneous tools. These improvement efforts require resources to evaluate and implement its activities that are normally part of the day-to-day job responsibilities of the individual organization. As a result, these business cases do not need to be considered as part of the organization’s project portfolio. Only those business cases where the scope, magnitude, and impact fall outside of the normal job responsibilities of the function will be considered for inclusion in the organization’s portfolio of projects and programs.

Usually for these types of projects at the most, a value proposition is all that needs to be prepared and approved by the function’s management team. In many cases, approval of these types of activities are either automatically approved by a memo or at a meeting where the activity is discussed and approved.

- Select and use a set of criteria aligned to the organization’s mission to classify and rank the business cases

The first step is to perform a general evaluation of each of the business cases to rate how it fits into the organization’s overall business structure. While this step should have been done as part of preparing the proposed business case, we have found it helpful to double check it at this point in the portfolio development stage of the life cycle. Each of the business cases should be reviewed against the following nine items to determine if it is in minimum compliance with the related criteria (Table 2.1).

Business Case Compliance with Key Business Considerations

#

Item

Criteria

1

Mission Statement

Must comply

2

Policy

Must comply

3

Vision Statement

Should comply

4

Values

Must comply

5

Strategy

Must comply

6

Critical for Success Factors

Need not comply

7

Business Objectives

Must comply

8

Organizational Goals

Should comply

9

Strategic Business Plan

Must comply

Any business case that contains one of the six items that should meet the “Must comply” criteria, but falls short of it, must be dropped from further consideration for the organizational portfolio. Any business case that meets all six of the “Must comply” criteria items, but has an item that doesn’t meet one of the two “Should comply” criteria, should still be given additional consideration during the evaluation cycle.

In addition, every business case should have, at a minimum, a “sustaining sponsor” identified and who will be held responsible for the success or failure of the project going forward.

- Determine which classification model to use: qualitative, quantitative, or blended

Now, there is a more granular and detailed approach to arriving at the criteria needed to classify and rank the projects and programs: one of three detailed classification or selection models: Qualitative, Quantitative, or Blended:

- A detailed selection model using “Qualitative” criteria provides an “anecdotal” or “subjective” perspective.

- A detailed selection model using “Quantitative” criteria provides an “empirical” or “objective” perspective.

- A detailed selection model using a “Blended” approach draws from both of the other two criteria providing a “dual” or “hybrid” perspective.

Depending on the set of criteria chosen to classify and rank the projects and programs as an input, you should determine which one of three detailed classification or selection models you are going to apply to arrive at that conclusion: a Qualitative one, a Quantitative one, or a Blended one.

Qualitative Classification Model1

There are five Qualitative models for classifying projects and programs.

- 1. C-Level Executive’s Pet Project: This type of project/program is a “personal favorite” of a politically influential or powerful senior executive in the organization and is usually submitted “de facto” without going through the normal classifying or screening process. If this executive isn’t the CEO, he needs to be sure that it gets ranked using the same model that is applied to all of the other projects/programs.

- 2. The Operating Necessity: This category is for those projects that are determined to be important in order to keep the organization running smoothly on a day-to-day basis.

- 3. The Competitive Necessity: This category is for those projects that are determined to be important in order to maintain the organization’s competitive position in its market or industry.

- 4. The Product/Service Line Extension: This category is for those projects that are determined to be important based on the degree to which they are aligned with the organization’s existing product or service line and extends it by filling a gap or strengthening a weakness to take it in a desired, strategic direction.

- 5. A New Product/Service Line: This category is for those projects that are determined to be important based on the degree to which they help execute the organization’s strategic plan by adding something completely new to its line of products and/or services.

Quantitative Classification Model2

Quantitative models for classifying or prioritizing projects and programs are broken down into two subtypes: “Profit/Profitability” models, of which there are five approaches, and “Scoring” models, of which there are four approaches:

- 1. Profit/profitability models subtype

- Payback Period: The initial fixed investment in the project is divided by the estimated annual cash inflows from the project. The resulting ratio is the number of years required for the project to repay its initial fixed investment. (Note: In order to qualify as a “Must Do” project, this value should be less than three years and, even better, less than two years.)

- Average Rate of Return: This is the ratio of the average annual profit (either before or after taxes) to the initial or average investment in the project.

The problem with the above two “simple” approaches is that neither one takes the concept of “the time-value of money” into account. Therefore, they should be considered only if interest rates and the rate of inflation are extremely low.

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF aka Net Present Value or NPV): This classification approach determines the net present value of all cash flows in the initiative by discounting them by the required “rate of return” (aka “hurdle rate” or “cut-off rate”). A positive net present value is desirable and preferable over a negative one.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR): The discounted rate (“k”) that equates the present values of both the expected cash inflows and outflows as the result of undertaking the project or program. The value of “k” is found by extrapolation or “trial and error.”

- Profitability Index (aka Benefit–Cost Ratio): The present value of all future expected cash flows divided by the initial cash investment in the project/program. A ratio of >1.0 is preferable and the higher the better.

Figure 2.2 is a snapshot of an Excel® spreadsheet template that incorporates all five of the above “Profit/Profitability” quantitative models with easy-to-use formulas embedded within it.

To use the spreadsheet in Figure 2.2, simply change one or more of the inputs, such as the Discount (interest) rate, the annual costs, and/or the annual benefits. The formulas are already entered into the Excel file used to create this template. Be sure to double check the formulas based on the inputs to calculate the ROI, NPV, and Payback Period. Since the “Payback arrow” currently appears in the first year in which a Positive Value exists (Year #2) for the current “Cumulative benefits–costs” (Row #16), the arrow should be moved (manually) to reflect the year that is the result for your data. Everything else gets calculated for you.

- 2. Scoring models subtype include:

- Unweighted 0-1 Factor Model: One or more OPT members are selected as “Classifiers” or “Raters” who score each project/program using a set of relevant unweighted binary factors or criteria (either “Yes” or “No”). Typical scoring factors include: “Is a ‘Green’ Project,” “Has High Potential Market Size ($),” “Has High Potential Market Share (percentage),” “Won’t Require New Facilities,” “Won’t Require New Expertise,” “Won’t Sacrifice Quality,” “Meets Profitability Target,” etc. Then, the projects and programs are rank-ordered based on the relative number of “Yes” scores. (Note: While this model allows for multiple criteria to be used, it’s assumed that all criteria are of equal importance with no scale. Quite often, this is not realistic.)

- Unweighted Scaled Factor Scoring Model: Conducted the same way as the previous model except that a 3-, 5-, 7-, or 10-point scale (with “1” as the lowest) is used and a discrete number is assigned to each unweighted factor or criteria. After that, the scores are added up, and the projects and programs are rank-ordered based on the relative score totals (with the highest score being classified highest, then, in descending order).

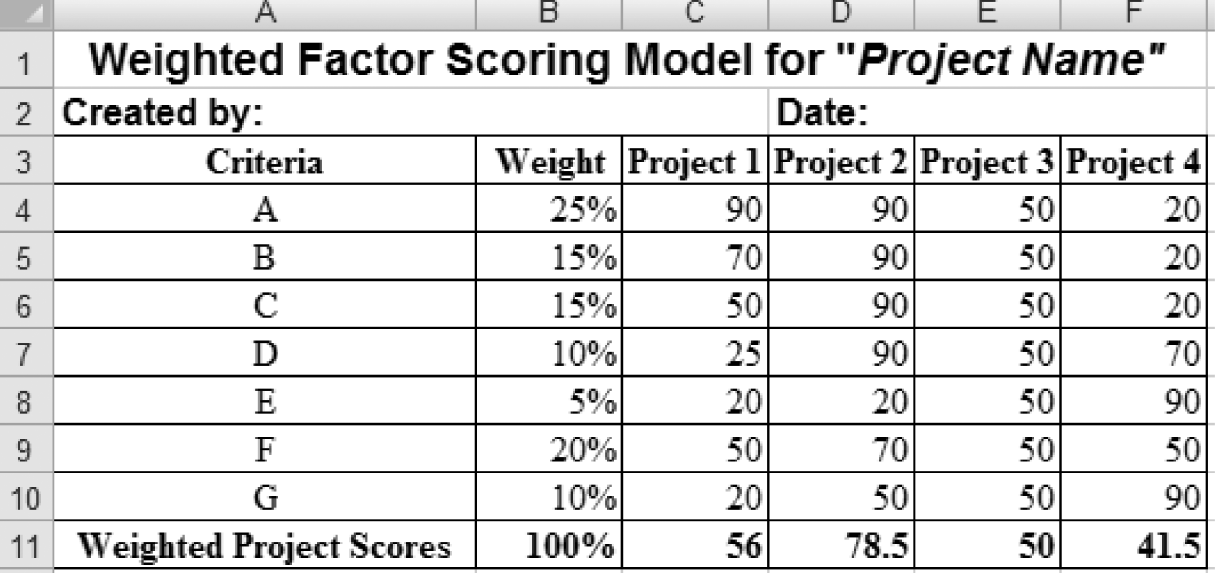

- Weighted Factor Scoring Model: One or more Portfolio Development Team members are selected as “classifiers” or “raters” who score each project/program using a set of relevant weighted and scaled values for each factor or criterion, based on a scale of 1 to 100 each. The weight (e.g., 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, etc.) of each criterion can be interpreted as the “percentage of the total weight accorded to that particular criterion.” (Note: Therefore, the total of all weighted factors should be 1.0 or 100 percent.) One of the potential weaknesses of this approach is the inclusion of one or more marginal criteria along with the substantial ones.

- Constrained Weighted Factor Scoring Model: This is conducted almost exactly as the previous model except that you define the marginal criteria as “constraints” instead of “weighted factors.” A constraint is a project characteristic that must be either present or absent in order for the project to be acceptable.

Figure 2.3 is a tabular example of a “Weighted Factor Scoring Model” in which Project 2 would be the highest ranked initiative (based on a scale of 1–100 points for each criteria based on its degree of compliance with it for each project) followed by Project 1, Project 3, and Project 4, respectively.

Figure 2.4 below is a graphic example illustrating the same data in ascending order by project number.

Blended Classification Model

A Blended Model for classifying or prioritizing projects and programs takes elements of both Qualitative and Quantitative models and combines them in a way that makes it easier to compare the various classified projects.

One of our favorite Blended Models for fulfilling this Phase I Activity is the Risk-Benefit Comparative Matrix Model, which presents all of the projects and programs being considered on a single graphic chart similar to the one for 25 projects in Figure 2.5.

In this example, we have classified the projects into five groups:

- 1. The “Low-Hanging Fruit” group (aka “Do-It-Now!”) of nine projects (#22, 23, 7, 5, 4, 19, 16, 15, 20) in the narrow, dotted rectangle on the far left of the light-grey “Top Zone” that requires taking a very low risk for a relatively high return or benefit.

- 2. Five projects (#3, 10, 14, 17, and 24) that are in the “Very Desirable” group (“Must Do”) in the center right of the same light-grey “Top Zone.”

- 3. Eight more projects (#1, 2, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, and 25) that are in the “Desirable” group (“Need to Do”) projects, which are in the “Upper Middle Zone.”

- 4. Two other projects (#8 and 18) that are in the “Less Desirable” group (“Nice to Do”) projects located in the “Lower Middle Zone.”

- 5. Project #21 that is in the only current “Undesirable” (“Defer”) project in the dark-grey “Bottom Zone” because there is only a medium potential benefit (value) in return for taking a very high risk (threat).

Outputs

- An executive committee review and approved ranked-ordered list of projects and programs based upon their potential value to the organization

The color-coded Comparative Matrix in Figure 2.5 also could serve as the basis for creating output for Activity #2: a rank-ordered, color-coded Organizational Portfolio. The five buckets or categories of projects and programs—“Do-It-Now” (Highest Priority), “Must Do” (Top Priority), “Need to Do” (2nd Priority), “Nice to Do” (3rd Priority), and “Defer at This Time” (No Current Priority—may be considered again in the future), and assigning each project or program to one of these categories.

Such an output could look like the rank-ordered spreadsheet in Figure 2.6. (We recommend that the items on the spreadsheet be color-coded if the organization is using computers to view the document and/or can print the spreadsheet in color as it makes it much more effective and useful to the reader.)

Note of Caution: Although the ranking approaches described above are relatively straightforward and structured to provide management with a prioritized list of projects/programs, they should not be blindly accepted in place of good judgment and common sense. While they do provide excellent guidelines, often there are other factors that may be as unsophisticated and informal as “gut feel,” intuition, or a key stakeholder’s extraordinary level of enthusiasm related to a specific project. We have seen very lucrative projects fail due to the “ho-hum attitude” of the project sponsor and/or the management team while other projects of much lesser value are very successful due to the enthusiasm and dedication of a few individuals within the organization.

The rank order of the proposed projects/programs is an extremely important output as it will have a big impact upon the future of most organizations. It is for this very reason that the rank-ordered list of projects/programs needs to be reviewed and approved by the executive committee. We find that frequently there are business reasons that have a major impact upon the way individual projects/programs are prioritized within the organization. For example, a market study may be a key input to making a decision related to a future strategic alliance. Another example is a commitment that has been made by the CEO to the Board of Directors related to a specific initiative. Based upon the executive committee review, the rank-order comparison spreadsheet should be modified to reflect their its inputs before it is finalized.

Activity #3: Prioritize the Projects and Programs Based on the Resources Available

Before any project or program should be undertaken, a minimum of the following three types of resources need to be available, or are scheduled to be available, when they are needed. The lack of having access to any one of these three types of resources will almost certainly cause the project(s) to fail.

- Adequate money needs to be available to finance the project/program.

- People with the proper skills need to be available to design, implement, and operate the project/program.

- Facilities need to be available, in keeping with the needs of the project/program.

Over the coming time period, resources are freed up because some of the existing projects are winding down or being completed. Completed projects often result in improved processes that require less manpower and financial support to produce the desired outputs. In some cases, production schedules are being decreased, freeing up both direct and indirect personnel. In other cases, productivity improvement, which often exceeds 10 percent per year, is freeing up personnel to be assigned to newly proposed projects.

During a typical budget cycle, projected sales and revenue generation estimates are prepared. At the same time, the Board of Directors establishes a minimum acceptable profit level that would be acceptable to the stockholders. Based on these two projections, a maximum operating budget can be established. The first obligation of the organization is to fund the currently approved project and programs. The remainder of the operating budget can be considered for the support of newly proposed projects and programs.

As a result, the first part of a normal budget cycle focuses on defining the amount of resources that are required to support the currently approved projects and programs. It also takes into account the impact that projects, which will be completed during the time period, will have on resource requirements. The result of this part of the budgeting cycle is the identification of a timeline with acceptable requirements for personnel, facilities, equipment, and financial resources required to support the currently approved projects and programs as they relate to each department within the organization. These requirements are then compared to the presently available personnel, facilities, and equipment to identify reassignable resources. The financial resources projected to support the current projects and programs are compared to the proposed maximum operating budget to identify what financial resources can be applied to the newly proposed projects/programs. Typically, the personnel comparisons will be done by HR. The facilities and equipment comparisons will be done by the Industrial Engineering Department, and the financial comparisons is the function of the Controllers.

Note

In small- to medium-sized organizations, this identification of present resources that can be reassigned to support new projects/programs is often done in a much less structured manner.

Below are the inputs, activities, and outputs for Activity #3:

- Input(s):

- An executive committee approved, ranked-ordered list of projects and programs based upon their potential value to the organization

- Manpower plans organized by function/department

- Documented performance and projected resource requirements for each project/program

- Activities:

- Determination of personnel, financial, and facilities requirements

- Assigning resources to prioritized projects/programs

- Analysis and comparison of the value content for currently active projects/programs

- Consideration of other resource alignment factors

- Presentation to the Executive Team

- Output(s):

- A list of new, resource-leveled, rank-ordered projects/programs that will be included in the organization’s active projects

- A list of new, rank-ordered projects/programs with no resources assigned and are deferred

- A list of projects/programs that are not recommended for implementation and, therefore, are dropped

- A written description for all approved projects and projects put on hold that includes the goals, objectives, and resource requirements

- Documented performance and projected resource requirements for each project/program

Inputs

- An executive committee-approved, ranked-ordered list of projects and programs based on their potential value to the organization

This is the sole output from the previous Activity (#2) in which each project and program has been evaluated, prioritized, and placed into one of the five buckets or categories of projects and programs below:

- 1. “Do-It-Now” (Highest priority; may be “low-hanging” fruit that can be done now with minimal effort and consumption of limited resources)

- 2. “Must Do” (Next highest priority)

- 3. “Need to Do” (3rd priority)

- 4. “Nice to Do” (4th priority)

- 5. “Defer at This Time” (No current priority; might be considered again in the future)

These prioritized projects and programs can be displayed in a graphic format (Figure 2.5), simple tabular format (Figure 2.6), or a spreadsheet format where they can be further defined in the ensuing steps in the process.

- Manpower plans by function/department

Once these projects and programs have been categorized and listed in rank order, the various functions or departments in the organization can perform “Manpower Planning” on each of them, in order of priority.

Manpower Planning consists of forecasting the right number and kinds of people at the right place, at the right time, doing the right things for which they are suited for the completion of the projects and programs in the organization’s portfolio. The result will be Manpower Plans by function/department based on those forecasts. These plans will be needed along with the rank-ordered Organizational Portfolio in order to complete this activity.

- Documented performance and projected resource requirements for each project/program

All major programs will have realistic business plans prepared and documented for them that include their goals, performance objectives, timing, and resource requirements.

- Manpower plans by function/department

Activities

- Determination of personnel, financial, and facilities requirements

Requirements for every project/program need to be addressed in three different ways:

- 1. Personnel requirements

- 2. Financial requirements

- 3. Facilities requirements

The first consideration is personnel requirements. In many organizations, the primary focus is on controlling the number of employees within the organization. This focus is brought about because management realizes that it makes a major commitment to an individual once he or she is hired. These commitments include the individual’s salary, benefits, and continued employment. In these organizations, the employee turnover rates are extremely important to keep at a minimum level because hiring and training employees is a major financial expenditure.

These organizations do everything possible to provide meaningful, value-added employment for the current employees and only add staff when there is a long-term potential for new staff to be added. These organizations look at their present employees as part of their assets rather than an expense. These types of organizations go out of their way to prepare careers for the current employees and rely on hiring supplemental temporary staff, consultants, and/or outsourcing to handle any short-term requirements.

In these cases, short-term requirements become more a matter of having sufficient funds available rather than personnel available. In many cases, having personnel available does not satisfy the needs of the proposed projects/programs because the people that are available do not have or are not capable of learning the required skills in time to support the proposed project/programs.

In the cases where the number of employees needs to be controlled, the number allocated to a specific location is usually defined by the Executive Team. The number of employees presently employed is usually maintained by either the HR Department or the Industrial Engineering Department. The workload for the present employees is defined during the budgeting cycle. Surplus employees are identified as a result of decreases in projected workload, committed productivity improvements, and continuous improvement programs.

Ideally, these surpluses are defined by the various functions within the organization and the skills that the surplus employees presently have. Based on the individual organization’s job descriptions, this type of information can be supplied by the organization responsible for coordinating the preparation of the budget in conjunction with the HR Department. This information is usually broken down by surplus per department per month.

The second consideration is the financial requirements. In organizations where the primary focus is on financial controls rather than human resources, the approach to determining which projects/programs will be included in the approved portfolio of projects/programs is much simpler. In these cases, where employees are looked at as a cost rather than an asset, surplus employees are assigned to new programs/projects only if that is the most economical way of doing business.

In this case, the decisions are made based on the cost of hiring temporary employees, training present employees in the skills required for the new assignments, the use of consultants, and the cost of hiring new full-time employees. In these cases, the Executive Team, in conjunction with the Board of Directors, establishes a targeted maximum yearly expenditure for the organization. This money is first distributed to the current ongoing projects and the remainder is set aside for discretionary spending, which includes new projects/programs. Today’s actual expenditures plus a good understanding of projected increases and decreases in activities and the projected committed performance improvement results would typically provide Finance the information needed to project financial requirements for the current activities. The delta between these financial projections and the maximum expenditures set by the Executive Team defines the discretionary spending that is allotted for activities like new projects/programs.

The third consideration is the facilities requirements. The two major facilities variables that need to be considered here are equipment and space.

Equipment facilities primarily refers to major items like mainframe computers, test equipment, milling machines, punch presses, clean room facilities, automobiles, and major pieces of software (CRM, MRP, etc.). Often as current projects become obsolete and/or eliminated, equipment facilities are freed up for the new projects/programs. When this is not the case, the additional costs need to be factored into the financial requirements along with the personnel effort required to install them.

Space is the other facilities variable that needs to be considered. Space includes warehousing, manufacturing floor space, office cubicles, filing areas, reproduction areas, and conference room space. Space is an important consideration because additional space to support new programs/projects would typically be established while the current products/programs are still utilizing their current space. Often temporary setups need to be established for the new programs/projects until activities on the current projects are reduced or eliminated. The organization’s Industrial Engineering Department (if one exists) should be able to provide the Portfolio Development Team with the organization’s available facilities.

- Assigning resources to prioritized projects/programs

As the Portfolio Development Team starts the job of assigning resources to the prioritized projects/programs, it has five important inputs that will be used to guide their activities:

- Assigning resources to prioritized projects/programs

- 1. A list of rank-ordered projects/programs.

- 2. A list of surplus employees by skills and department. That may include the maximum number of employees allotted for the organization.

- 3. The maximum amount of discretionary spending money that can be allotted to the projects and programs.

- 4. An individual from a function/department like industrial engineering that understands the availability of facility resources.

- 5. The organization’s strategic plan.

Starting with the highest priority project/program, the Portfolio Development Team will analyze and define the resource requirements for the project/program and assign personnel, financial, and facility resources to each of the programs/projects. Each time a resource is assigned, the remaining amount of resources available to lower priority projects is decreased by the value of the assigned resource. This process is repeated until the available resources are exhausted. Unfortunately, this usually occurs before all of the proposed programs’/projects’ resource requirements have been fulfilled. When this occurs, the Portfolio Development Team needs to look at currently active projects/programs in an attempt to maximize the value added to the organization in the total portfolio of projects and programs.

- Analysis and comparison of the content value of the current active projects/programs

Very often, identified available resources are totally used up before all of the proposed new projects have resources assigned to them. In these cases, an assessment should be made of the current approved projects/programs to ensure that their value-added content and projected impact based upon current data would justify them being canceled in favor of one or more of the proposed new projects/programs. Often, in today’s rapidly changing business environment, projects that were projected to be highly lucrative have diminished in luster and it is more beneficial to the organization to terminate them in favor of a newly proposed project. When this occurs, the Portfolio Development Team should make a list of the current projects/programs that they recommend should have the resources reduced or should be eliminated, and document how these work resources would provide better value to the organization if they were applied to specific proposed projects/programs.

- Consideration of other resource alignment factors

As the reader must realize by now, this activity is very complex. However, there are two other factors that must be considered when assigning resources: timing and possible future shock.

- Analysis and comparison of the content value of the current active projects/programs

- 1. Timing: For example, consider the following. The highest priority project is scheduled to start May 1 and requires three programmers to be assigned for the rest of the year. A lower priority project is scheduled to start on January 1 and requires three programmers until June 15. The data indicates that there were four programmers available for the entire year. In this case, the simplest answer would be to assign three of the programmers to the highest priority project starting May 1 and hire temporary supplementary programmers to handle the needs of the other projects. In that case, we would have three internal programmers who would not be utilized for four months. To eliminate this waste of the programming resources, the Portfolio Development Team would need to look into the possibility of using four programmers on the second project so that it could be completed by May 1 and/or the possibility of slipping the programming needs in the high level project by a month and a half.

- 2. Possible Future Shock: Assigning too much change activity to an individual part of the organization might cause it to go into future shock. An individual part of the organization can be involved in so many different change initiatives that it is no longer able to handle the stress that is put on the area as these changes are taking place. This situation is called future shock and, at that point, the area becomes dysfunctional. To minimize the possibility of an individual organization going into future shock, the Portfolio Development Team needs to understand the amount of change activity that is going on within the individual areas of the organization and recommend to the executive committee that projects are scheduled so that the stress within individual parts of the organization does not exceed its ability to function in a responsible manner. As a general guideline, no more than two major changes should be going on in an individual part of the organization simultaneously. That is the maximum that the area can handle effectively.

- Presentation to the Executive Team

The Portfolio Development Team should schedule a meeting with the Executive Team to present and review its recommendations. This presentation should include a detailed analysis of how available resources were assigned to the project/programs based on their prioritized order. It also should present the current projects that the Portfolio Development Team is recommending to have their activities reduced or to be completely eliminated and how these actions would free up resources that could be applied to the newly proposed projects/programs.

The Portfolio Development Team should present as well the list of projects/programs that did not have resources assigned to them along with recommendations related to their future potential or if they should be dropped from consideration. Sometimes this results in the Executive Committee increasing the resources available in order to include additional proposed programs/projects in the active portfolio.

Outputs

As a result of Activity #3, the proposed lists of new projects/programs are divided into three major output lists:

- 1. A list of new, resource-leveled, rank-ordered projects/programs that will be included in the organization’s active projects.

- 2. A list of new, rank-ordered projects/programs with no resources assigned and are deferred.

- 3. A list of projects/programs that are not recommended for implementation and, therefore, are dropped.

Also,

- Documented performance and projected resource requirements for each project/program.

- A written description for all approved projects and projects put on hold that includes the goals, objectives, and resource requirements.

In addition, a list of current active projects/programs that are recommended for completion and another list of those current active projects/programs that are recommended to have their resources reduced or termination in favor of one or more of the newly proposed projects/programs should be prepared and presented by the Portfolio Development Team.

Activity #4: Select Projects and Programs for the Portfolios and Assign a Portfolio Leader to Oversee Them

The purpose of this activity is to group together projects/programs in a manner where a Portfolio leader can be assigned to monitor them with the objective of keeping them on time and within budget while producing the desired business results. Below are the inputs, activities, and outputs for Activity #4:

- Input(s):

- A list of all resource-leveled, rank-ordered projects/programs

- A list of all current active projects/programs/portfolios

- A list of qualified portfolio leaders

- A list of initiating sponsors for all current and approved projects/programs

- Activities:

- Select the subportfolio(s) for the current Organizational Portfolio

- Match each subportfolio by assigning a qualified Portfolio leader to it

- Outputs:

- A list of resource-leveled, rank-ordered proposed projects/programs in the portfolio with each one’s assigned portfolio leader

- A list of initiating sponsors for all current and approved projects/programs

- A list of portfolio leaders with subportfolios and projects/programs assigned

- A list of all current active projects/programs/portfolios

DCC Portfolio Leader

Background context: The Data and Coordination Center (DCC) is responsible for coordination of and data capture for a multicenter consortium of Clinical Centers of Excellence providing annual screening examinations, mental and physical health treatment, public health reporting, and investigation of health outcomes among a heterogeneous, multilingual population of over 34,000 patients. The Portfolio leader will have responsibility for managing the DCC’s Portfolio of Projects.

Position summary: The Portfolio leader’s responsibilities will be to oversee and coordinate three to five complex performance improvement, data management, and scientific investigation projects to ensure that multiproject deliverables and timelines involving a diverse team of physicians, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, social workers, informaticists, and data management specialists are identified, scheduled, and met. The Portfolio leader will report directly to the DCC principal investigator/director.

Primary Responsibilities:

- Direct and support the development of a portfolio of comprehensive project plans and timelines in collaboration with the four DCC Core Teams (Health Outcomes, Clinical Coordination, Community Outreach/Social Services, and Data Management) to implement strategic priorities; establish goals, define deliverables/timeframes, and evaluate performance with the goal of ensuring that federally mandated deliverables are completed and provided on a timely basis.

- Direct and support tracking, monitoring, and controlling the above-described portfolio of comprehensive project plans and timelines with the goal of ensuring that federally mandated deliverables are completed and provided on a timely basis.

- Has full accountability for the creation, implementation, and facilitation of a portfolio of projects related to federal grant program deliverables including public health reporting and disease surveillance, data entry and cleaning, creation of analytic datasets, and coordination of clinical outcomes reporting, including administration of scientific writing groups and provision of assistance in manuscript preparation and progress tracking.

- Facilitate timely and responsive integration amongst and between the Health Outcomes, Data Management, Clinical Coordination, Social Services/Community Outreach, and Informatics teams, principal investigators, the funder, and other key stakeholders, including responder organizations, public health, and labor unions.

- Post on the shared drive and maintain a read-only portfolio comprised of project-related records to allow for secure access to multiple, cross-organizational project plans for managing internal and external resources to ensure all schedules and deliverables are met.

- Develop and maintain a portfolio status reporting system to track implementation schedules, deliverables, and resources on a weekly basis.

- Develop and maintain processes to identify and report obstacles/barriers that could prevent the DCC from meeting its portfolio and project objectives.

- Act as liaison between the Leadership Core members and Core Team leaders.

- Responsible for internal cross-project communications. Ensure that all team members are informed of changes in direction or any other information related to their ability to perform their role on one of the projects or the program as a whole.

- Take the lead role in issue resolution for projects, mediate conflicts, and ensure that key people are included in issue resolution on a timely basis.

- Work with the Institutional Review Board and the HIPAA Compliance Team to ensure conformance with regulatory requirements.

- Identify process and workflow “bottlenecks” and recommend changes required to implement the DCC’s strategic goals.

- Support the creation of project plans with milestones and work with the project managers and their team members to assure that project deliverables are completed on time and within budget.

- Track, communicate, and manage all portfolio implementation issues.

- Review all portfolio and project reports for accuracy and compliance with programmatic goals.

Experience/Requirements:

- 10+ years of project management experience with at least 2 of those years in a leadership role within a Project Portfolio environment.

- Experience in either medical informatics, public health, biopharmaceutical, biotechnology, medical devices, or a Clinical Research Organization (CRO) or Data Center is highly desirable.

- Understanding of data management for public health and scientific reporting is essential.

- Must have excellent interpersonal and leadership skills, as well as strong communication, problem solving, and organizational skills.

- Experience in planning and implementing biomedical, operational, and/or administrative information systems applications and integration strategies is strongly desired.

- Excellent verbal and writing skills and demonstrated aptitude for problem solving.

- Excellent analytical skills.

- Must possess working knowledge and understanding of relational databases.

- Must be proficient in accounting principles as they relate to the design of performance reports.

Education/Certification:

- Master’s degree in medical informatics, epidemiology, biostatistics, information technology, computer sciences, healthcare management/administration, public health, or its equivalent required; doctoral degree preferred.

- Certification in Project, Program, and/or Portfolio Management, Lean Six Sigma, or their equivalent is required.

Inputs

- A list of all resource-leveled, rank-ordered projects/programs

To accomplish this activity, the list of current, active projects/programs and the list of prioritized business cases that are recommended for having resources assigned to them are combined. This allows similar or relevant projects/programs to be grouped together into separate portfolios.

- A list of all current active projects/programs/portfolios

The number of projects/programs that can be effectively managed by a Portfolio leader will vary based on the complexity of the respective project/program, the core competencies required to manage a specific type of project/program, the physical location at which the project is being implemented, and the timing of the project/program. As a general rule of thumb, an effective Portfolio leader will be able to handle from three to five projects simultaneously. Very often, individual portfolios of projects/programs are created for new products, marketing, information technology, and personnel-related initiatives.

- A list of qualified Portfolio leaders

It is extremely important that knowledgeable and effective individuals are recruited, selected, and assigned as Portfolio leaders. To assist the Human Resources Department in finding and selecting competent Portfolio leaders, a comprehensive job description should be created that is modeled after the one provided below for a Data and Coordination Center.

In sum, just like the Portfolio Development leader, the Portfolio leader must be a very special individual. However, the Portfolio Development leader is a temporary type operation and often this individual’s permanent job will be in strategic planning, personnel, or managing a project office. In large organizations where there are a number of Portfolio leaders and/or project managers, a department called Project Management Office (PMO) is formed. In these cases, the Portfolio leaders and the professional project managers reside as members of the PMO and they are responsible to the manager of the PMO, who is responsible for coordinating the activities that are going on between all of the Portfolio leaders.

Each Portfolio leader is only responsible for managing a delegated set of projects/programs. That being the case, the Portfolio leader should focus on planning, executing, monitoring, and controlling a set of high-priority projects and programs. He/she should have the following credentials:

- Possesses at least a bachelor’s degree, but, in some cases, a master’s degree

- Is highly respected throughout the organization

- Possesses certification in Project Management or Program Management from a recognized professional society, or hold a master’s degree in Project Management from an accredited institution.

Additional traits to look for in selecting the Portfolio leader include:

- Understands the importance of his/her portfolio of projects and programs

- Trusted leader

- Self-starter

- Good listener

- Excellent communicator

- Politically savvy

- Has detailed knowledge of the business

- Understands processes

- Customer-focused

- Passionate

- Strong motivator