4

Motivation and Academic Learning

Evelyne CLÉMENT1 and Alain GUERRIEN2

1PARAGRAPHE, CY Cergy Paris Université, Gennevilliers, France

2PSITEC, Université de Lille, France

4.1. Introduction

Motivation, defined as the internal and/or external forces that initiate the triggering, direction, intensity and persistence of behavior (Vallerand and Thill 1993), is often cited as one of the determinants of success in various areas of personal, professional or academic life. It is linked to emotional processes and contributes greatly to learning. We will see, for example, that it can lead to the persistence of efforts made by students and positively influence the emotional reactions they experience when they encounter difficulties during learning. Thus, the major questions that drive psychological research on the links between motivation and academic learning cover a wide spectrum.

Without claiming to be exhaustive, we can define these research questions in the following way. What factors are implied in the student’s involvement in academic learning? What is the respective part played by the student’s psychological dispositions and educational practices in this involvement? What are the consequences of motivation on academic success and perseverance when students are faced with difficulties or challenges? What are the consequences of motivation on school persistence or school drop-out? What consequences on student’s well-being and their emotional state? How do these consequences feed back into academic motivation?

The research conducted on motivation in the school context thus attempts to answer these questions by focusing on the nature of the processes that are at the origin of students’ involvement in academic learning and the consequences of this motivation on the student’s relationship with this learning in particular and, more generally, with school.

In this chapter, after presenting the three main theoretical approaches to motivation that are currently most influential in the field of learning and education and highlighting their common principles, we will develop the consequences of the different ways of being motivated in academic work, in particular the consequences on academic performance, subjective evaluation of one’s own competence, perseverance in the face of difficulty or even on well-being. In the third section, on the basis of empirical work, we will identify a number of suggested levers that can promote optimal academic motivation and that are the subject of consensus in the literature.

4.2. Different approaches to academic motivation: theoretical aspects

4.2.1. Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan and Deci 2017) is an approach to motivation that has become very influential since the 1980s. This is because of the insights it has provided into the different reasons why people engage in certain activities and the practical implications it has. It has provided a framework for a great deal of research in various fields, including education. These studies have contributed to a better understanding of the dispositional and contextual factors that contribute to students’ engagement in academic activities, success and well-being.

For what reasons might a student engage in an academic activity? SDT answers this question by identifying different types of motivation (Deci and Ryan 2016; Ryan and Deci 2017). An initial distinction is made between intrinsic motivation (IM) and extrinsic motivation (EM) (Deci and Ryan 1985).

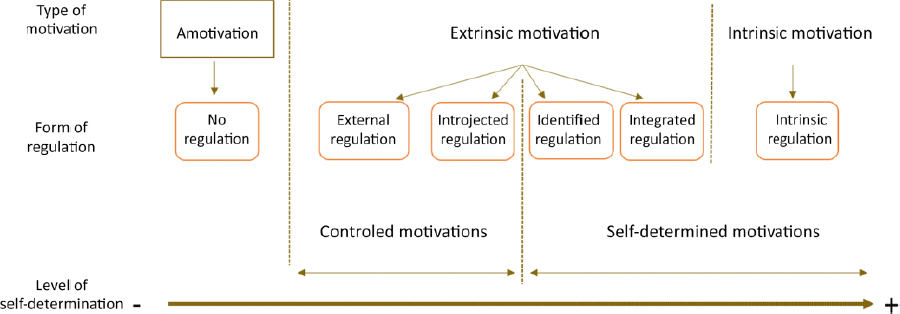

In the context of SDT, this dichotomous conception of IM and EM has been cast aside in favor of the idea of a continuum presenting different types of motivational regulation on an axis of self-determination (or autonomy), the self-determination corresponding to the fact that the individual acts by exercising his or her will and free choice (Figure 4.1).

Thus, IM is the most self-determined form of motivation, because it is manifested in behaviors guided by interest, curiosity, research and the pursuit of challenges (Koestner and Losier 2002). As for EM, it is found in different forms (Deci and Ryan 2016). External regulation is the least self-determined EM: behavior is controlled by external forces, such as constraints imposed by the teacher or the academic institution. It is often related with obtaining rewards or avoiding punishment. Introjected regulation corresponds to a somewhat higher level of self-determination: the activity is no longer carried out because of external pressures but rather because of internal pressures, for example to avoid a feeling of guilt. This is the case of the student who performs an activity to please their parents and avoid the feeling of shame that could result from poor results. Next comes identified regulation whereby the student engages in an activity by choice because they consider it important, particularly in terms of the objectives they are pursuing (e.g. in the context of their educational orientation and professional project). In this way, the student adheres to the value of the action and is therefore relatively self-determined, even if this action is still part of an EM because it is carried out with a view to its consequences (diploma, job, etc.). Finally, integrated regulation – the most self-determined and closest to IM – refers to actions that the student performs because of the importance they attach to them, insofar as they are in line with their values. This type of regulation may, for example, lead a student to spend time helping another student with their schoolwork, because the student generally values solidarity and cooperation.

Box 4.1. Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation

Today, in the context of SDT, the opposition between IM and EM has been cast aside in favor of a distinction between self-determined (or autonomous) motivation, which includes IM and EM through integrated regulation and identified regulation, and controlled motivation, which includes EM through introjected regulation and external regulation (Figure 4.1). This distinction is fully justified by a clear differentiation in terms of cognitive, affective and behavioral consequences – discussed below – with self-determined motivation being associated with the most favorable results.

Figure 4.1. The self-determination continuum from Deci and Ryan (2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/habib/emotional.zip

Beyond these distinctions between different types of motivation, another aspect of SDT has been to identify three basic psychological needs, the degree of satisfaction of which gives rise to self-determined motivation and well-being (Deci and Ryan 2002):

- – The need for autonomy corresponds to the need for the person to feel that they are the origin of their behavior rather than a “pawn” controlled by external forces (deCharms 1968). It refers to the feeling of freedom and choice in activities.

- – The need for competence corresponds to the need to feel effective in the activities undertaken (White 1959), to exercise and express one’s abilities.

- – The need for affiliation concerns the quality of relationships with others and refers to feeling supported by people important to oneself and belonging to a group (Baumeister and Leary 1995).

On this basis, it appears that the more students perceive themselves as autonomous, competent and affiliated with others in their school activities, the more their motivation tends to be self-determined. Conversely, less satisfaction of these needs tends to foster a controlled type of motivation (Reeve 2002; Vallerand and Miquelon 2016; Ryan and Deci 2017).

4.2.2. Achievement goal theory

Achievement goal theory is another approach, which has also generated a large body of literature presenting research conducted in academic settings.

The initial version of this theory (Dweck and Elliott 1983) is based on the distinction between two types of goals that a student may have: mastery goals and performance goals. A student pursues a mastery goal when their objective is to progress in an activity: to improve their competence and mastery level in a given activity. This type of goal can be described as intrapersonal, in that it involves a process of temporal comparison: evolution of competence by the student between an initial time and a later time. On the other hand, a student pursues a performance goal if their objective is to show superiority over other students. This type of goal is normative because it involves a social comparison process: individual performance is this time compared with that of other individuals. A typical example in an academic context is the goal of advancing in a ranking among students.

Subsequently, this approach has undergone several redesigns aimed at overcoming its dichotomous nature. A differentiation was established according to whether the student considers that they can succeed or fail in the task. Approach behaviors (seeking the positive consequences of success) and avoidance behaviors (avoiding the negative consequences of failure) are then distinguished. Thus, Elliot and Harackiewicz (1996) made a distinction between two types of performance goals: performance-approach goals (the student’s goal is to show their competence to others) and performance-avoidance goals (the student’s goal is to avoid showing incompetence). This differentiation between approach and avoidance was later extended to mastery goals (Elliot 1999; Pintrich 2000): having a mastery-approach goal consists of seeking to improve one’s personal competence in an activity, whereas having a mastery-avoidance goal leads the individual to seek to avoid making mistakes or regressing.

Finally, Elliot et al. (2011) have further extended the model. These authors distinguish three ways of defining one’s competence: with reference to mastery of the task, with reference to oneself (the individual’s personal trajectory) and with reference to what others do. These three standards are combined with the notions of approach and avoidance. Thus, six motivational achievement goals are identified (3 2 model): (1) mastery-approach (e.g. for a student to master a task); (2) mastery-avoidance (to avoid making a mistake); (3) self-approach (to get better at the task); (4) self-avoidance (to avoid doing worse than before); (5) other-approach (to do better than other students); and (6) other-avoidance (to avoid doing worse than other students).

4.2.3. The self-efficacy theory

According to Bandura (2003), a sense of self-efficacy (SSE) is the foundation of motivation. It is defined as “the individual’s belief in his or her ability to organize and execute the course of action required to produce desired results” (Bandura 2003, p. 12).

In the academic setting, then, an SSE is concerned with students’ beliefs about their ability to master various academic subjects. It helps to determine students’ choices of activities, their investment in the goals they have set for themselves, their persistence of effort and the emotional reactions they experience when they encounter difficulties. If a student is not convinced that they can achieve the results they want through their own actions, there is little reason for them to engage in academic activities and persevere in the face of difficulties. Thus, Bandura gives the SSE an important status in the cognitive regulation of motivation. According to the author, students:

They develop beliefs about what they can do, anticipate the likelihood of positive and negative outcomes of various activities, and set goals and plan programs of action to achieve a future outcome. They develop beliefs about what they can do, anticipate the likelihood of positive and negative outcomes of various activities, and set goals and plan programs of action designed to achieve a desired future and avoid an unpleasant one. (Bandura 2003, p. 188)

Bandura (2003) indicates that the SSE is determined by four sources of information: (1) active experiences of mastery (previous performances, successes and failures); (2) vicarious experiences (modeling and social comparison); (3) verbal persuasion (evaluative feedback, encouragement and opinions of significant others); and (4) physiological and emotional states.

Active mastery experiences serve as an indicator of ability. According to Bandura, they are the main source of SSE. Thus, the students’ previous academic performance and their academic career gradually shape their beliefs of effectiveness, provided, of course, that they feel responsible for their successes and failures. For students with difficulties, if activities present a moderate challenge, then the multiplication of successes and observations of progress feeds their SSE and their interest in the proposed activities (Schunk 1989).

Vicarious experiences based on the observation of social models modify the SSE through the transmission of skills and comparison with what other students do. For example, for a student, observing another student succeeding in a task may generate an anticipation of success in a similar situation and thus have a positive effect on their sense of efficacy, especially since they share different characteristics with the model (in terms of skills, grade, age, gender, etc.). Social comparison also feeds into the SSE on the basis of an external frame of reference (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2002) that allows the student to situate themselves within a group of students, and thus to evaluate their competencies with reference to the class average, for example. This external frame of reference is coupled with an internal frame of reference that allows the student to compare their current performance with their previous performance, which also contributes to the development of their SSE.

Verbal persuasion refers to the messages sent to the student by teachers, peers or parents, whose support, encouragement, advice or expressed expectations also contribute to the SSE. Evaluative feedback is, of course, an important form of verbal influence conveying information about the degree of mastery achieved by the student. According to Bandura (1977), the feedback that is most likely to enhance the student’s SSE is that which informs the student of the ways in which they can be more successful in the future. In fact, Butler (1988) shows that feedback about how a piece of work can be improved leads to higher interest and performance than feedback in the form of grades or praise.

Finally, the students’ interpretation of their physiological and emotional states also informs about their own competence. Feeling stressed in the face of a task is interpreted as a sign of vulnerability, which can alter the SSE (Bandura 2003). Conversely, excitement in the face of a challenge can reinforce the belief in efficacy.

4.2.4. Common principles between these different approaches

Today, the three theoretical approaches to motivation presented above are the most influential in various fields, including education. They are solidly supported by a considerable body of scientific literature, all three have their own coherence and their contribution to the understanding of motivation and its regulation is significant. While respecting their specificities, it is possible to identify common principles. In all three approaches, the students’ perception and evaluation of their ability to succeed in a task or to achieve a goal, as well as social and environmental factors, play an important role in motivating the student to engage in a learning task.

Conceptually, the notions of perceived competence described in the SDT and the SSE proposed by Bandura are very similar. The same is true for the notion of achievement goals. In this case, as we have seen above, the students evaluate their competence either in terms of the progress they make during the learning process (mastery goal) or by comparing their own performance with that of others (performance goal). Perceived competence here is determined by the type of goal pursued by the student who engages (approach goal) or does not (avoidance goal) in the learning task.

Much more than just the students’ personal characteristics or the characteristics of the social environment in which they live, it seems that it is the interaction between these two factors that determines the motives underlying engagement in learning. For example, an academic environment that supports students’ self-esteem strengthens their sense of competence in school work (Ryan and Grolnick 1986) and leads to fewer dropouts (Vallerand et al. 1997). Conversely, a teaching practice that leaves less room for student initiative provides less feedback on progress and efforts to be continued, is less attentive to students and less accepting of student difficulties and is deleterious.

Recently, Leroy et al. (2013) proposed a social cognitive model of school learning that integrates the SDT approach and Bandura’s social cognitive theory. In their model, the authors retained the teacher’s motivational style – supporting the three psychological needs of autonomy, competence and social affiliation – as a social contextual factor. As for the students’ motivational variables, the various forms of self-determined motivation, amotivation and SSE were selected. Students’ perception of their teacher’s motivational style was introduced into the model as a mediating variable between the teacher’s self-supportive motivational style and the students’ motivational processes. Results from a large number of students and teachers validate the model. The more support students perceived from their teachers for the needs of competence, autonomy and social affiliation, the more self-determined motivation, self-efficacy and low amotivation they exhibited. In addition, self-determined motivation, low amotivation and feelings of self-efficacy each predicted better academic performance.

The importance of the social environment has also been emphasized in the framework of the achievement goal theory. Darnon et al. (2006) point out that most of the studies reported in the literature have focused on the influence of mastery and performance goals without taking into account the influence of social factors that may interact with these goals. In academic learning situations, it is difficult to imagine that the gaze of others and the group does not influence students’ behavior. In order to study the differential impact of the presence of others on behaviors motivated by mastery or performance goals, the authors report a laboratory study in which the goals were manipulated by the instructions given to the participants. Students were asked to engage in cooperative work on comprehension of a text. Participants were told that they would be working in pairs with another student via a computer. In reality, the exchanges with the supposed partner were pre-programmed for each participant in order to study the interaction effects of goals, disagreements between partners and learning. For some, a mastery instruction was presented, emphasizing acquisition of new knowledge and comprehension of the text, for others a performance goal was induced by an instruction emphasizing performance (getting a good score on a final MCQ1). Learning performance was measured by the students’ answers to an MCQ given at the end of the experiment. The results show interaction effects between the nature of the achievement goal and the sociocognitive conflict caused by disagreements. In the mastery goal condition, sociocognitive conflict led to better learning. Exchanges and disagreements with the partner were an opportunity to process the text in greater depth. In this condition, possible exchanges and disagreements with others were sources of progress, as others were perceived as a source of information about the task to be performed. In the performance goal condition, the opposite was true. Disagreements between partners deteriorated the quality of learning. In this case, others were perceived as a source of threat to skills.

4.3. Different ways of being motivated: what consequences?

Beyond the definition of the different types of motivation that the approaches described above have made it possible to identify, research has highlighted a certain number of consequences for academic learning.

4.3.1. Consequences according to the SDT

In the context of SDT, authors distinguish three categories of consequences: behavioral, cognitive and affective (Guay et al. 2008; Guay and Lessard 2016).

At the behavioral level, perseverance and academic success have been essentially linked to motivational orientation. It appears that intrinsic motivation, and more broadly self-determined motivation, is associated with greater persistence in the curriculum. For example, the study by Vallerand et al. (1997) indicates that self-determined motivation predicts a lower dropout rate in high school, while according to the study by Blanchard et al. (2004), controlled motivation is associated with more unjustified absences and intentions to drop out. Vansteenkiste et al. (2004) show that self-determined motivation is associated with more persevering learning behaviors (particularly reading and extra work). Furthermore, a number of studies have shown that self-determined motivation is associated with better success in high school (Guay and Vallerand 1997; Guay et al. 2010) and university studies (Alivernini and Lucidi 2011).

Self-determined motivation has also been linked to various cognitive consequences in the context of learning. For example, it has been shown to be associated with better learning strategies leading to greater depth of processing (Vansteenkiste et al. 2004; Kusurkar et al. 2013) and metacognitive strategies such as self-assessment of progress, error analysis or task planning (Oxford and Ehrman 1995). It generates more cognitive engagement (Reeve 2002), resulting in better attentional focus on the task (Amabile 1983) and better attentional maintenance (Guerrien and Mansy-Dannay 2003), and also less perceived fatigue (Mansy-Dannay and Guerrien 2002). It is also associated with more creativity (Amabile 1996). Finally, students with high levels of self-determined motivation have a greater propensity to engage in challenging activities (Boggiano et al. 1988).

In terms of affective consequences, Vallerand et al. (1989) showed that students with higher self-determined motivation experience more positive emotions in class and more satisfaction with their studies. Students with this profile also have lower levels of anxiety (Black and Deci 2000). Much work from the perspective of SDT has also linked self-determined motivation and psychological well-being. This research is in line with the eudemonic conception of well-being (Ryan and Deci 2001), which considers that self-determined motivation and the satisfaction of the three needs of autonomy, competence and affiliation are determinants of psychological well-being. Sheldon’s work with students is situated within this framework: the achievement of goals produces an increase in students’ psychological well-being in cases where these goals are self-determined (or “self-concordant”) and where success positively feeds the satisfaction of the three needs (Sheldon 2002; Halusic and Sheldon 2016).

4.3.2. Consequences according to the achievement goals theory

Numerous classroom and laboratory studies have examined the results of the nature of goals on students’ engagement in academic learning. There is a broad consensus in the literature on motivational achievement goals about the positive consequences of mastery and skill development goals and the negative results of performance demonstration goals (Dutrévis et al. 2010).

In research conducted with first-year psychology students enrolled in university, Elliot et al. (2011) proposed and tested their model of the six goals described above: task-centered goals consisting of mastery-approach (succeeding at the task) and mastery-avoidance (avoiding engaging in a task that one has not mastered), self-centered goals with self-approach (doing better than before) and self-avoidance (avoiding doing worse than before), and other-centered goals with other-approach (doing better than others) and other-avoidance (avoiding doing worse than others). In order to test the results of the different achievement goals (experiment 2), several variables were retained by the authors: academic performance was assessed on the basis of (1) a success score on three course-related exams, (2) intrinsic motivation, (3) perceived efficacy in learning (e.g. “I can understand difficult concepts in the course if I try”), (4) exam anxiety, (5) interest and attention to the course (cognitive absorption) and (6) active participation (engagement) in the course. Regression analyses of the data collected from over 300 students show differentiated patterns across the different goals and variables.

Overall, the results show that mastery-focused goals, including mastery-approach goals, are positive predictors of intrinsic motivation, perceived efficacy in learning, and interest and attention in the course, while self-approach goals are not related to any of these variables. On the other hand, other-focused goals are predictors of perceived efficacy in learning, and self-approach goals are related to active participation in class. Finally, regarding academic performance, self-approach goals are associated with better performance, while self-avoidance goals are associated with poorer performance. The authors point out that this set of results is consistent with those reported in the literature. Self-approach goals are conducive to performance but are not related to students’ subjective experience of competence, whereas the various avoidance goals, whether they are mastery-focused, self-focused or other-focused, have negative consequences not only on performance but also on students’ subjective experience of competence.

In general, all of the work carried out within the framework of the achievement goal theory shows that goals focused on mastery of the task have beneficial effects, particularly mastery-approach goals. In this sense, many research studies have shown that engagement in learning tasks, in order to progress in mastery of the task and to develop one’s skills, is associated with intrinsic motivation where learning is achieved for its own sake, that this engagement is associated with better academic performance and better perceived competence (Elliot et al. 2011). In addition, pursuing a mastery goal allows for the apprehension of difficulties encountered by adopting strategies for success (Dweck 1999). Finally, although performance goals have been found to be generally less conducive to learning, being associated with negative emotions and reduced effort (Sarrazin et al. 2006), these goals, particularly performance-approach goals, can have beneficial effects on students’ motivation in the academic domain (Dutrévis et al. 2010).

4.3.3. Consequences according to the SSE

School-based research on the SSE has amply demonstrated its important role in student engagement and performance. Students with a high SSE are more likely to engage in challenging activities, set higher goals, and regulate their efforts better, persevere more in the face of difficulties, are less anxious and achieve better results (Multon et al. 1991; Bandura 2003; Galand and Vanlede 2004). It appears that the SSE plays an indirect role on performance: it promotes engagement in activities, which in turn has an effect on performance. Thus, the study by Bouffard et al. (1998) shows that the perception of competence promotes commitment to the task, self-regulation in carrying it out, effort, perseverance and emotional reactions to difficulties encountered, which leads to better performance.

Another particularly interesting contribution is that competence beliefs contribute to performance independently of, rather than as a mere reflection of, cognitive skills themselves (Bandura 2003). The study by Collins (1982, cited by Bandura (2003)) thus shows distinct effects of SSE and ability level in mathematics problem solving. Indeed:

Students may perform poorly either because they lack the necessary skills or because they have them but lack the perceived self-efficacy to make optimal use of them. (Bandura 2003, p. 326)

The SSE plays an important role in mobilizing and applying skills, and in this way contributes to performance that is not solely due to skill level.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing the importance of the SSE in aspirations for further education toward higher levels of schooling (Bandura et al. 1996), as well as in the construction of career choices. Lent et al.’s (1994) model focuses on describing and understanding the processes involved in the development of students’ educational and vocational interests, and thus in career choices. The SSE and outcome expectations play an important role in career choices, insofar as they contribute to the construction of interests.

4.4. Promoting optimal motivation at school: what are the levers?

Research that has identified different types of motivation and highlighted their positive or negative results for academic learning provides a framework for thinking about the teaching practices most likely to foster optimal motivation in students.

In the context of SDT, the notion of autonomy support has given rise to a great deal of research in recent years, and to recommendations for application in an academic context. In this perspective, the focus is on the teacher’s interpersonal style, which is found to be crucial for students’ motivation (Moreau and Mageau 2013; Sarrazin et al. 2014). Indeed, the teacher plays a crucial role with regard to the motivation of their students through the climate they establish in their classroom, which can support autonomy, and allows students to satisfy their needs for competence, autonomy and affiliation and thus promote a more self-determined motivation, or conversely be more controlling, that is leading to the frustration of psychological needs and harming self-determined motivation.

Reeve (2002, 2006) has clarified the fundamental differences between the two teaching styles. Supporting students’ autonomy involves:

- – listening to them carefully;

- – creating opportunities for them to work in their own way;

- – giving them opportunities to express themselves;

- – creating situations where they can act and exchange rather than passively listen and watch;

- – encouraging effort and perseverance;

- – highlighting their progress;

- – giving them advice to progress when they are struggling;

- – answering their questions;

- – demonstrating an understanding of their point of view.

Supporting autonomy ultimately means being more responsive to students, more positive, more flexible and more explanatory.

Conversely, autonomy-threatening behaviors consist of:

- – managing alone and imposing the learning content;

- – giving the solution and answers right away without giving the students time to look for the solution on their own;

- – giving “correct answers” without allowing time to discover them;

- – giving orders;

- – using vocabulary related to constraint (“you must”, “I want that”, etc.);

- – asking questions that dictate how to work (“can you do what I showed you?”).

In short, to be controlling is to have a tendency to take over everything, to be more negative, to be motivated by pressure and to appear more “hurried” by not allowing students the time to search for themselves. A great deal of research now shows how students’ perception of a climate that supports their autonomy is conducive to their self-determined motivation as well as their SSE and has positive results on their learning and success (Leroy et al. 2013; Moreau and Mageau 2013).

This approach in terms of motivational climate and interpersonal style complements the numerous studies that have made it possible, also in the context of the SDT, to shed light on the conditions most conducive to intrinsic motivation, that is the interest that students may have in an activity and the pleasure that they may derive from doing it. The activities most conducive to intrinsic motivation are those that present an “optimal challenge” for the student (Deci and Ryan 1985), that is that have a level of complexity within their reach but just above their current level of competence (Mansy 1990), so that success is possible but not guaranteed. It is in this case that eventual success will foster a sense of competence, which will increase the student’s propensity to engage again later, in a self-determined manner, in this same type of task. The question of adapting activities to the student’s skills is therefore crucial in terms of motivation. The feedback provided to the student by the teacher is also particularly important. The SDT emphasizes the importance of positive and informational feedback (Deci and Ryan 1985). Feedback is positive if it emphasizes progress and success, and acknowledges the effort made, even if it is less successful. It is informational if its content allows the students to better attribute responsibility for success or progress (internal locus of perceived causality) and feeds their sense of competence by allowing them to better understand their success. In the event of a poor result, such feedback is constructive in that it provides information on better ways of working in the future (by not repeating the same mistakes, by changing strategy, etc.). Feedback ensures that failures do not result in a drop in the feeling of competence and intrinsic motivation.

The motivational climate in the classroom can also be viewed from the angle of mastery or competition climates (Ames 1992). A climate of mastery is established by the teachers if their activity is focused on the students learning, their individual progress and the recognition of their work and efforts. A climate of competition is established when the emphasis is placed on social comparison and competition between students. More specifically, a climate of mastery implies that students have opportunities for choice and initiative regarding the nature and level of complexity of the tasks in which they engage (Sarrazin et al. 2006). It implies that the teacher encourages effort and values progress, while giving errors a constructive status; that they form flexible and heterogeneous work groups to encourage cooperation; that they allow students to work at their own pace; and that they implement assessment practices based on personal performance standards.

The competitive climate, on the other hand, is characterized by non-personalized activities decided solely by the teacher. Encouragement aimed at rewarding the best-performing students – with level groups explicitly determined, differences in learning pace not taken into account, and assessment based on social standards of performance – and of a public nature (rankings announced to all students) contributes to this climate.

For its part, Bandura’s social cognitive theory has largely explained the sources of the SSE (Bandura 2003), which can also be used to reflect on the pedagogical practices most conducive to student motivation: active experiences of mastery, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and physiological and emotional states. Students’ efficacy beliefs are first and foremost the product of their accumulated past experiences, successes and failures. These active experiences of mastery are, according to Bandura, the main source of the student’s SSE, insofar as they testify to their abilities. Of course, these experiences can either positively or negatively contribute to the SSE, provided that the student takes responsibility for them, in terms of competence or effort. External attributions (e.g. attributing success to luck or the ease of the task) are not conducive to shaping the SSE. Research in this area sheds light on the pedagogical situations that are most conducive to active mastery experiences that are conducive to SSE, in terms of task difficulty and the hierarchical structure of goal systems. It is indeed the “moderately” difficult tasks (with regard to the student’s level of competence) which, representing a moderate challenge, generate the most effort and interest and provide information likely to increase the belief in effectiveness. Moreover, this confrontation with such tasks is all the more effective when it is integrated into a program that includes proximal, short-term goals, and distal goals that are more distant goals. The former allows for immediate perceptions of gradual progress, which reinforce the SSE, while the latter, which is more distant in time, guides current activities by setting broader objectives (Bandura and Schunk 1981).

Students’ SSE is also influenced by the vicarious experiences of observing models and making comparisons with others. Students observe social models that are meaningful to them and draw conclusions about their own effectiveness. Thus, for a student, observing the successes and failures of other students on a task can modulate their SSE (Schunk and Hanson 1989), especially since they can identify with the observed student (in terms of age, gender, grade level, etc.). Social comparison also allows the student to assess their own competence, for example by comparing themselves to the class average, or to other selected students (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2002). While these social comparisons are made spontaneously by students, they can also be used intentionally by adults. For example, in the context of the issue of stereotypes related to mathematics performance, Bagès et al. (2016) presented students with more advanced “model students” who had succeeded due to their efforts. This confrontation resulted in girls doing as well as boys on a mathematics test, regardless of whether the model was a girl or a boy, as long as the model was presented as “hardworking”, compared to a model that was presented as “gifted” or whose success would not be explained. Exposure to such a model of success increases perceived competence, and consequently performance in mathematics.

The student’s sense of efficacy is also fueled by the verbal persuasion of others, that is the messages that are addressed to them: support, encouragement, advice, criticism, expectations, etc. Teachers play a crucial role here by giving feedback to students on their progress. The challenge is to use feedback to deliver messages of encouragement that can improve subsequent performance through an increase in the SSE (Jackson 2002). According to Bandura (2003), the message that best reinforces the student’s SSE is the one that focuses on the means that they can acquire to better master the task later.

Finally, the fourth source of academic SSE is physiological and emotional states (Bandura 2003). The interpretation that the student may make of their sensations and emotional states during the performance of a task is likely to affect their perception of competence. Feeling stressed is a signal of vulnerability that can lower confidence in one’s abilities. Conversely, a state of excitement in the face of a challenge can have a positive effect on that confidence. Bandura emphasizes how academic activities are often disrupted by anxiety and stress: a low sense of efficacy is accompanied by high levels of anxiety, which in turn fuel disruptive anticipatory thoughts (worrying about future failures, imagining scenarios of poor performance, etc.) that further weaken the SSE. In particular, the highly anxiety-provoking effects of the threat generated by certain evaluative practices based on a climate of competition or interpersonal comparison need to be addressed.

4.5. Discussion

The three approaches on which this chapter is based – SDT, achievement goal theory and self-efficacy theory – provide a solid and diversified framework for better understanding academic motivation, its dynamics, determinants and consequences. They also highlight the extent to which the teacher plays a fundamental role in motivating students, through the motivational climate they establish (supporting autonomy vs. controlling; mastery vs. competition), through the nature of the activities in which they get them to engage (optimal challenge, meaning of the activities with regard to the goals pursued, etc.), through the perceptions of efficacy that these activities generate in their very performance or through the feedback they provide. It is within this framework that various authors have proposed a certain number of “recommendations” for promoting optimal motivation through teaching practices (Reeve 2002, 2006; Sarrazin et al. 2006).

Of course, while academic motivation is largely determined by the student’s experiences in the school context, this motivation is also dependent on extracurricular factors. Children and adolescents accumulate experiences in various contexts, all of which can contribute to their self-perception and motivation to learn. The hierarchical model of motivation proposed by Vallerand (1997) and Vallerand and Miquelon (2016) is particularly illuminating on this point. The model is based on the SDT, and motivation (intrinsic, extrinsic) is understood according to three hierarchical levels of generality:

- – situational motivation (a “state” motivation for a given activity at a given time, “here and now”, and then in an ascending manner);

- – contextual motivation (related to a field of activity, e.g. school);

- – global motivation (general motivational orientation as a personality trait, general propensity to act intrinsically or extrinsically).

For each of these three levels, motivation is underpinned by specific perceptions (situational, contextual and global) relating to the basic needs of autonomy, competence and social belonging. Dynamically, motivation can be modulated by bottom-up effects (situational motivation influences contextual motivation, which in turn can affect global motivation) or top-down effects (from global motivation to contextual motivation and then to situational motivation). For example, the completion of an academic activity at a given time may be characterized by a high level of intrinsic motivation, associated with good perceptions of autonomy, competence and social belonging. This positive experience can have a bottom-up effect on intrinsic motivation for education (school contextual motivation). This shows how the day-to-day experiences at school (situational motivation) shape the broader motivation for school (contextual motivation), and how crucial the “situations” created by the teacher are. However, children and adolescents also act in areas other than the academic context: the context of leisure time, the context of activities in the family, etc. Motivational dynamics must therefore also be considered from a cross-domain perspective, because motivation in one context can influence motivation in another. Thus, for example, leisure activities can have an effect on school motivation. The fact that activities are carried out more or less self-determinedly in one context can have an effect on motivation in another context. Furthermore, it should be considered that the accumulation of activities in various contexts can generate (bottom-up) effects at the global level, which in turn can affect, through top-down effects, contextual and situational motivations. For example, a child’s overall sense of competence may be fed by good performance in leisure activities (bottom-up effect), and have a beneficial top-down effect for school activities. Clearly, while teachers play a major role in the motivational dynamics of their students, this motivation is embedded in a larger, complex system.

The teacher’s role has also been examined in terms of the effect of their own motivation on that of their students. If, as has been shown by the research presented in this chapter, the teacher plays a major role in the academic motivation of students, the study of the different motives for their commitment is a valuable contribution to understanding the motivational dynamics that take place in the classroom. In this sense, many research studies have focused on this issue and have highlighted that the way teachers are motivated in their professional practice influences the motivational climate they establish in the classroom and has consequences on their students’ motivation, their sense of competence and their well-being (Butler 2007; Dresel et al. 2013; Mascret et al. 2015, 2016).

Within the achievement goal theory, while much research has been conducted on students’ goals in school learning, the study of teachers’ motivational goals is more recent (Butler 2007). Research findings from this approach suggest that teachers’ motivational goals influence their own learning experiences and practices as well as their students’ motivation and learning. Teachers’ mastery goals are associated with professional skill development, learning and help-seeking practices, while performance goals are more associated with experiences of stress and maladaptive professional behaviors (Butler 2007; Nitsche et al. 2011). More recently, Mascret et al. (2015) tested Elliot et al.’s (2011) previously described 3 2 model with high school teachers. By asking teachers to answer different questionnaires, the authors studied the links between teachers’ motivational orientations and the motivational climate established in the classroom (e.g. “I try to identify the progress of each student, even if they are below the expected level” or “I encourage my students to do better than others”), teachers’ representations of competence (e.g. “It is difficult to change your level of intelligence” or “It takes a lot of work to be smart”), as well as intrinsic motivation (e.g. “I try to find interesting topics and new ways to teach, because it is fun to create new things”). The results show that the different motivational goals are related to the selected variables. Teachers motivated by a mastery-approach goal more often set up a motivational climate of mastery, valuing their students’ effort, learning and personal progress. As for the goals centered on the self, that is to progress in one’s professional practice for the self-approach goal, or to avoid doing less well than before for the self-avoidance goal, they are associated with an implicit theory of competence, understood as being modifiable and linked to effort and perseverance. Finally, intrinsic motivation is associated with the mastery and self-approach goals.

Other research on teacher motivation has looked at teachers’ SSE. Overall, it has shown links between teachers’ SSE and student achievement, perceived efficacy and academic motivation. Moreover, teachers with a high SSE are more likely to welcome students with behavioral difficulties into their classrooms, to manage the stress of conflict situations, whereas teachers with a low sense of efficacy experience more negative emotions related to stressful classroom situations and tend to respond with punitive methods (Gordon 2001; Gaudron et al. 2012). In their review of the literature on teachers’ SSE and their practice in managing classrooms and challenging student behaviors, Gaudron et al. advocate using during teacher training the four sources of SSE development proposed by Bandura (2003): (1) providing active experiences of mastery; (2) having peers share and observe the successes of others to enrich vicarious experiences, (3) offering personalized coaching and encouraging through verbal persuasion; and (4) offering reflective analysis of professional practices to raise awareness of the physiological and emotional states provoked by experiences in the contexts of classroom management and difficult student behaviors.

To conclude, as has been emphasized in this chapter, the teacher’s role is decisive in the academic motivation of students. In order to better understand this role in the diversity and dynamics of school motivation, it seems necessary to take into account the motivational climate established by the teacher, which is itself dependent on the teacher’s own motivational orientations and SSE. In order to establish classroom practices conducive to optimal student motivation, it is necessary to recommend to trainee and in-service teachers levers to foster such motivation.

4.6. Conclusion

In this chapter, we have seen that the relationship between motivation and the student’s emotional state is twofold, because emotional state (such as anxiety, excitement or well-being) influences the student’s engagement in learning. On the other hand, the type of motivation can influence the emotional state, because students with higher self-determined motivation experience more positive emotions in class and more satisfaction with their studies. We have focused on the consequences that students’ motivation may have on their engagement in school learning and, more generally, their relationship with school. The results of the research presented here have demonstrated the effect of the motivational climate established by teachers on their students’ achievement. However, a naive and simplistic interpretation of these results could lead one to think that it is enough to create more “motivating” teaching contexts consisting of attractive “packaging” (e.g. playful materials and use of digital tools). If they are not thought out in terms of the meaning perceived by the students, the goals to be achieved, and clear objectives in terms of progress, such contexts can only produce beneficial effects in the very short-term. These different media can be of interest in terms of motivation and the learning and appropriation of knowledge by students, if they meet the real challenges described in this chapter. In short, the aim is to create motivating situations that do not distract from the meaning and content of learning.

4.7. References

Alivernini, F. and Lucidi, F. (2011). Relationship between social context, self-efficacy, motivation, academic achievement and intention to drop out of high school: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(4), 241–252.

Amabile, T.M. (1983). The Social Psychology of Creativity. Springer Verlag, New York.

Amabile, T.M. (1996). Creativity in Context. Westview Press, New York.

Ames, C. (1992). Achievement goals and the classroom motivational climate. In Student Perceptions in the Classroom, Schunk, D.H., Meece, J.L. (eds). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., Mahwah.

Bagès, C., Verniers, C., Martinot, D. (2016). Virtues of a hard-working role model to improve girls’ mathematics performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40, 55–64.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (2003). Auto-efficacité. Le sentiment d’efficacité personnelle. De Boeck, Brussels.

Bandura, A. and Schunk, D.H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 586–598.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G., Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67, 1206–1222.

Baumeister, R.F. and Leary, M.R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Black, A.E. and Deci, E.L. (2000). The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self-determination theory perspective. Science Education, 84(6), 740–756.

Blanchard, C., Pelletier, L., Otis, N., Sharp, E. (2004). Rôle de l’autodétermination et des aptitudes scolaires dans la prédiction des absences scolaires et l’intention de décrocher. Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 30, 105–123.

Boggiano, A.K., Main, D.S., Katz, P.A. (1988). Children’s preference for challenge: The role of perceived competence and control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 134–141.

Bouffard, T., Markovits, H., Vezeau, C., Boisvert, M., Dumas, C. (1998). The relation between accuracy of self-perception and cognitive development. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68(3), 321–330.

Butler, R. (1988). Enhancing and undermining intrinsic motivation: The effects of task-involving and ego-involving evaluation of interest and performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 58(1), 1–14.

Butler, R. (2007). Teachers’ achievement goal orientation and association with teachers’ help seeking: Examination of a novel approach to teacher motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 241–252.

Collins, J.L. (1982). Self-efficacy and ability in achievement behavior. Document, Annual Meeting of American Education Research Association, New York.

Darnon, C., Buchs, C., Butera, F. (2006). Buts de performance et de maîtrise et interactions sociales entre étudiants : la situation particulière du désaccord avec autrui. Revue française de pédagogie, 155, 35–44.

deCharms, R. (1968). Personal Causation: The Internal Affective Determinants of Behavior. Academic Press, New York.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (eds) (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-determination in Human Behavior. Plenum Press, New York.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (eds) (2002). Handbook of Self-determination Research. University of Rochester Press, New York.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2016). Favoriser la motivation optimale et la santé mentale dans divers milieux de vie. In La théorie de l’autodétermination : aspects théoriques et appliqués, Paquet, Y., Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. (eds). De Boeck, Brussels.

Dresel, M., Fasching, M., Steuer, G., Nitsche, S., Dickhäuser, O. (2013). Relations between teachers’ goal orientations, their instructional practices and students’ motivation. Psychology, 4, 572–584.

Dutrévis, M., Toczek-Capelle, M.C., Buchs, C. (2010). Régulation sociale des apprentissages scolaires. In Psychologie des apprentissages scolaires, Crahay, M., Dutrévis, M. (eds). DeBoeck, Brussels.

Dweck, C.S. (1999). Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality and Development. Psychology Press, Philadelphia.

Dweck, C.S. and Elliott, E.S. (1983). Achievement motivation. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Mussen, P.H., Hetherington, E.M. (eds). Wiley, New York.

Elliot, A.J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist, 34, 169–189.

Elliot, A.J. and Harackiewicz, J.M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 461–475.

Elliot, A.J., Murayama, K., Pekrun, R. (2011). A 3 x 2 achievement goal model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 632–648.

Galand, B. and Vanlede, M. (2004). Le sentiment d’efficacité personnelle dans l’apprentissage et la formation : quel rôle joue-t-il ? D’où vient-il ? Comment intervenir ? Savoirs, 5, 91–116.

Gaudron, N., Royer, E., Beaumont, C., Frenette, E. (2012). Le sentiment d’efficacité personnelle des enseignants et leurs pratiques de gestion de la classe et des comportements difficiles des élèves. Canadian Journal of Education–Revue Canadienne de l’Éducation, 35, 82–101.

Gordon, L.M. (2001). High teacher efficacy as marker of teacher effectiveness in the domain of classroom management. Document, Annual Meeting of the California Council on Teacher Education, San Diego.

Guay, F. and Lessard, V. (2016). La théorie de l’autodétermination appliquée au contexte scolaire : état actuel des recherches. In La théorie de l’autodétermination : aspects théoriques et appliqués, Paquet, Y., Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. (eds). De Boeck, Brussels.

Guay, F. and Vallerand, R.J. (1997). Social context, students’ motivation, and academic achievement: Toward a process model. Social Psychology of Education, 1, 211–233.

Guay, F., Ratelle, C.F., Chanal, J. (2008). Optimal learning in optimal contexts: The role of self-determination in education. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 233–240.

Guay, F., Ratelle, C.F., Roy, A., Litalien, D. (2010). Academic self-concept, autonomous academic motivation, and academic achievement: Mediating and additive effects. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(6), 644–653.

Guerrien, A. and Mansy-Dannay, A. (2003). Attention soutenue et motivation : une approche chronopsychologique. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 44(4), 394–409.

Halusic, M. and Sheldon, K.M. (2016). La théorie de l’autoconcordance : pourquoi le fait de choisir les bons objectifs peut faire toute la différence. In La théorie de l’autodétermination : aspects théoriques et appliqués, Paquet, Y., Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. (eds). De Boeck, Brussels.

Jackson, J.W. (2002). Enhancing self-efficacy and learning performance. The Journal of Experimental Education, 70, 243–254.

Koestner, R. and Losier, G.F. (2002). Distinguishing three ways of being highly motivated: A closer look at introjection, identification, and intrinsic motivation. In Handbook of Self-determination Research, Deci, E., Ryan, R. (eds). University of Rochester Press, New York.

Kusurkar, R.A., Cate, T.J.T., Vos, C.M.P., Westers, P., Croiset, G. (2013). How motivation affects academic performance: A structural equation modelling analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 57–69.

Lent, R.W., Brown, S.D., Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122.

Leroy, N., Bressoux, P., Sarrazin, P.G., Trouilloud, D. (2013). Un modèle sociocognitif des apprentissages : style motivationnel de l’enseignant, soutien perçu des élèves et processus motivationnels. Revue française de pédagogie, 182, 1–19.

Mansy, A. (1990). Aspects théoriques des motivations cognitives. In Activités physiques et sportives, efficience motrice et développement de la personne, Pfister, R. (ed.). AFRAPS, Clermont-Ferrand.

Mansy-Dannay, A. and Guerrien, A. (2002). Motivation, sentiment de compétence, agrément et fatigue ressentie après la séance d’enseignement au collège. Revue de psychologie de l’éducation, 7, 58–75.

Mascret, N., Elliot, A.J., Cury, F. (2015). The 3 x 2 achievement goal questionnaire for teachers. Educational Psychology, 17, 7–14.

Mascret, N., Maiano, C., Vors, O. (2016). Buts motivationnels d’accomplissement des enseignants : l’influence de l’appartenance à un établissement “difficile” et de l’ancienneté. Revue française de pédagogie, 194(1), 29–46.

Moreau, E. and Mageau, G.A. (2013). Conséquences et corrélats associés au soutien de l’autonomie dans divers domaines de vie. Psychologie française, 58(3), 195–227.

Multon, K.D., Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 30–38.

Nitsche, S., Dickhäuser, O., Fasching, M.S., Dresel, M. (2011). Rethinking teachers’ goal orientations: Conceptual and methodological enhancements. Learning and Instruction, 21, 574–586.

Oxford, R.L. and Ehrman, M. (1995). Cognition plus: Correlates of language learning success. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 67–89.

Pintrich, P.R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of Self-regulation, Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M. (eds). Academic Press, San Diego.

Reeve, J. (2002). Self-determination theory applied to educational settings. In Handbook of Self-determination Research, Deci, E., Ryan, R. (eds). University of Rochester Press, New York.

Reeve, J. (2006). Teachers as facilitators: What autonomy-supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. The Elementary School Journal, 106(3), 225–236.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness. Guilford Press, New York.

Ryan, R.M. and Grolnick, W.S. (1986). Origins and pawns in the classroom: Self-report and projective assessment of individual differences in children’s perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 736–750.

Sarrazin, P., Tessier, D., Trouilloud, D. (2006). Climat motivationnel instauré par l’enseignant et implication des élèves en classe : l’état des recherches. Revue française de pédagogie, 157, 147–177.

Sarrazin, P., Pelletier, L., Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.R. (2014). Nourrir une motivation autonome et des conséquences positives dans différents milieux de vie : les apports de la théorie de l’autodétermination. In Traité de Psychologie Positive, Martin-Krumm, C., Tarquinio, C. (eds). De Boeck, Brussels.

Schunk, D.H. (1989). Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 1, 173–208.

Schunk, D.H. and Hanson, A.R. (1989). Self-modeling and children’s cognitive skill learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 155–163.

Sheldon, K.M. (2002). The self-concordance model of healthy goal striving; when personal goals correctly represent the person. In Handbook of Self-determination Research, Deci, E., Ryan, R. (eds). University of Rochester Press, New York.

Skaalvik, E.M. and Skaalvik, S. (2002). Internal and external frames of reference for academic self-concept. Educational Psychologist, 37(4), 233–244.

Vallerand, R.J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Zanna, M.P. (ed.). Academic Press, New York.

Vallerand, R.J. and Miquelon, P. (2016). Le modèle hiérarchique de la motivation intrinsèque et extrinsèque : une analyse intégrative des processus motivationnels. In La théorie de l’autodétermination : aspects théoriques et appliqués, Paquet, Y., Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R. (eds). De Boeck, Brussels.

Vallerand, R.J. and Thill, E.E. (1993). Introduction au concept de motivation. In Introduction à la psychologie de la motivation, Vallerand, R.J., Thill, E.E. (eds). Études Vivantes – Vigot, Laval.

Vallerand, R.J., Blais, M.R., Brière, N.M., Pelletier, L.G. (1989). Construction et validation de l’échelle de motivation en éducation (EME). Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 21(3), 323–349.

Vallerand, R.J., Fortier, M.S., Guay, F. (1997). Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1161–1176.

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K.M., Deci, E.L. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic role of intrinsic goals and autonomy-support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 246–260.

White, R.W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66, 297–333.

- 1 Multiple-choice questionnaire.