8

Trauma, Cognition and Learning

Serge CAPAROS

DysCo, Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, France

8.1. Learning: learner, content and context

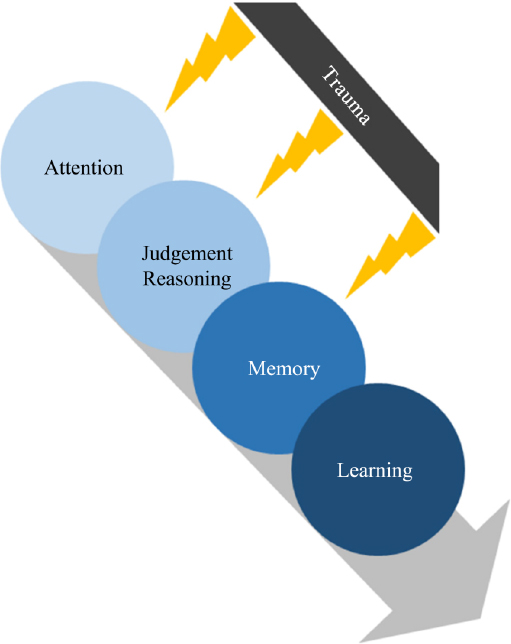

Learning involves a learner (the actor) whose aim is to acquire new knowledge or a new skill (competence). Knowledge or skill acquisition involves a set of cognitive processes that allows new information to be processed (attention), associated with other information already known (judgment, reasoning) and encoded for future reuse (memory).

Successful learning, that is the actual acquisition of knowledge or skills, depends on a large number of factors, such as the strategies used during learning, the quality of the pedagogical techniques offered by the teacher (if any), the learner’s prior proficiency (proximal zone of development), and also the context in which learning takes place. This context can refer, on the one hand, to the local context the learner finds themselves in (e.g. material conditions: a high school student will be more likely to acquire new knowledge if they have satisfactory material conditions, such as a chair, desk, notebook, pencils and books). The learning context can also refer to the more global context surrounding the learner, that is to say the general characteristics of their environment: their country’s degree of political and social stability, their living environment, social circle, socio-economic conditions and personal history. It is on this last point that this chapter focuses, and more particularly on an important element of the learner’s history: the stressful life experiences to which they have been exposed. Several studies (e.g. Klein and Boals (2001); Sliwinski et al. (2006); Stawski et al. (2006)) demonstrate a chronic impact of stressful experiences on the individual’s cognitive and emotional functioning, which is likely to have significant – and negative – consequences on their learning abilities. In this chapter, we will focus on the most stressful experiences, those likely to leave serious psychological wounds: traumatic experiences. We will document how certain traumatic contexts can negatively impact different stages of the cognitive chain that enables learning.

Figure 8.1. Trauma, cognition and learning. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/habib/emotional.zip

We will discuss several studies and literature reviews that have documented the negative consequences of trauma on learning, and we will propose mechanisms that could explain these negative consequences. Research on trauma, and in particular on its cognitive and affective consequences, is relatively recent. This research first focused on American veterans who survived the Vietnam War, some 40 years ago (Schnyder 2005). It was then extended to victims of sexual violence and abuse during childhood. Today, this research sometimes goes beyond Western borders – which traditionally compartmentalize scientific psychology – and focuses on populations living in non-Western countries, which represent the majority (85%) of the world’s population and which are more often exposed to traumatic experiences, due to the political instability and armed conflicts characteristic of many developing countries.

Education is identified as a key factor in development and stability in low- and middle-income countries, and in increasing equality of opportunity in high-income countries. Since traumatic exposure can negatively affect prospects for success in educational programs, the question of the link between trauma and learning deserves the full attention of psychologists. The first task is to document the links between these variables and then to explain them. Finally, strategies must be suggested to mitigate the negative consequences of trauma on learning. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief overview of recent knowledge on these issues. This review is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather to provide opportunities for reflection and bibliographic references for readers interested in this subject.

8.2. Trauma

8.2.1. Definition of a traumatic event

Trauma is a psychological injury generated by a life experience. This experience, the traumatic event, is a violent event of an unpredictable nature, interrupting the normal course of the individual’s life and resulting in the generation of emotions of an extreme intensity, far greater than the intensity of the emotions felt in daily life. The emotions in question are, by definition, negative in nature. They include fear, in the vast majority of cases, but can also include anger, guilt, shame, sadness, despair, helplessness, disgust and a host of other negative emotions that the individual experiences during and after the traumatic event. The range of emotions generated can vary depending on the type of event (rape vs. natural disaster) and on the individual (Amstadter and Vernon 2008). Some emotions (such as shame) are more often associated with the subsequent development of psychopathological symptoms.

The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) (American Psychiatric Association 2015) suggests the following list of events with traumatic potential: fighting, sexual violence, physical assault, serious injury, burglary, kidnapping, terrorist attacks, torture, natural disasters, motor vehicle accidents, serious illness, witnessing the death of or serious injury to others, witnessing violent attacks and war, etc. The common feature of all these events is that they involve a serious risk of death, violence and/or serious injury. In short, the physical integrity and survival of an individual exposed to one (or more) of these events are seriously in question, which explains the extremely intense emotional experience generated by these events.

8.2.2. A traumatic or potentially traumatic event?

A violent event (e.g. rape) has an objective definition (non-consensual, coerced sex) and includes a set of objective characteristics, such as place and time, duration and the level of violence involved. When an event is qualified as traumatic, it is described in terms of its consequences (short-term and long-term) for an individual’s psychological health: the event generated trauma. It should be noted that an event should only be described as traumatic if it has actually had negative psychological consequences. It is incorrect to say that a rape is necessarily a traumatic event, because the same experience of sexual violence will not necessarily generate the same psychological consequences in all individuals. Some people will develop a severe pathology as a result of the experience (see section 8.2.3), while others will not develop any pathology. It is therefore preferable to speak of a potentially traumatic event to emphasize the inter-individual variability of psychological responses.

In short, potentially traumatic events are life experiences that will generate an intense and negative emotional response in individuals and have the potential to create psychological injury in some. This psychological injury may remain weeks, months or years after the event.

8.2.3. The psychological injury generated by traumatic exposure

A person exposed to a potentially traumatic event is likely to develop psychopathological symptoms that have the potential to have significant negative consequences on the individual’s life. The greater the intensity of the symptoms, the more disabling they are. Beyond a certain intensity – the clinical threshold – we speak of pathology.

The most common pathology observed following a traumatic exposure is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD consists of a series of symptoms that are expressed in an intense and chronic way in the individual. It has four major dimensions:

- – Reliving the event, that is to say the tendency to relive the event in the form of nightmares or memories giving the impression of being confronted with the violent event.

- – Avoidance, that is making an effort to try not to think about the circumstances of the event, or the tendency to avoid all situations in everyday life that might remind one of the event.

- – Negative thoughts and moods, which involve the experience of overly negative affects, losing interest in doing things, feeling isolated and having difficulty experiencing positive emotions.

- – Physiological changes, which are a set of changes in the individual’s internal state, such as hypervigilance, reacting in a startled way, irritability and sleep problems.

PTSD is a very common condition that can be experienced at any age. Once the condition develops, it may subside on its own over time. But if the person does not receive appropriate treatment, it can persist for years or decades (see Box 8.1). There are various psychotherapeutic approaches to alleviating trauma-related injuries, many of which have proven to be effective (Schnyder 2005).

Box 8.1. The case of PTSD in Rwanda

Another pathology frequently observed in populations exposed to trauma is depression. This pathology is a comorbidity of PTSD, as approximately one-half to two-thirds of individuals with PTSD also suffer from it (Tapia et al. 2007; Suliman et al. 2009; Rytwinski et al. 2013).

8.3. Impact of trauma on learning

A growing number of studies have focused on the effects of trauma on different dimensions of learning (Perfect et al. 2016). Some of these studies, which have taken place in Western countries, have focused on the effects of child abuse or sexual violence. Others have taken place in low- and middle-income countries and have focused on the effects of violence related to armed conflict.

These studies assume that individuals (and particularly children) whose primary needs – such as safety – are not met will have more difficulty reaching their full cognitive potential, and this will have a direct effect on their learning abilities. Several models propose that individuals exposed to trauma direct all or part of the resources necessary for learning toward the management of the trauma (Conte and Schuerman 1987; Shanok et al. 1989). This redirection of resources disrupts cognitive development and reduces academic performance.

Exposure to violence has been associated with agitation and behavioral problems in the classroom (Pynoos et al. 1987; Dyson 1990), decreased school attendance (Bowen and Bowen 1999; Hurt et al. 2001), increased repeating of a school year (Schwab-Stone et al. 1995; Lipschitz et al. 2000) and a general decline in academic performance (Salzinger et al. 1984; Zimrin 1986; Duplechain et al. 2008).

Duplechain et al. (2008) examined the relationship between the exposure to trauma during childhood (witnessing violence or experiencing the loss of a parent) and reading ability in a sample of 163 children (7–11 years-old) over a 3-year period. The results showed that traumatic exposure slowed the development of reading ability and that this effect was more pronounced in highly exposed children than in moderately exposed ones. A similar effect of trauma has been reported in other studies (Delaney-Black et al. 2002).

Porche et al. (2011) studied a sample of over 2,000 adolescents. They showed that traumatic exposure increased the risk of school dropout by 50%. The most damaging traumatic experiences were childhood abuse and domestic violence between parents. Traumatic events such as serious car accidents or natural disasters also increased the likelihood of academic failure.

Larson et al. (2017) conducted a review of pediatric studies on the effects of trauma conducted between 2003 and 2013 in the United States. The majority (80%) of the studies considered showed negative effects of trauma on the academic trajectory of children and adolescents. Exposed individuals generally had poorer academic performance, fewer and poorer academic opportunities and poorer prospects in the workplace after leaving school.

Also in the United States, Boyraz et al. (2013) studied the relationship between PTSD and academic performance in 600 college freshmen. The study focused on students of African American descent, who are statistically more likely to be exposed to traumatic events (because they are more likely to live in areas prone to violence and have fewer financial and social resources to protect themselves from said violence). In the study sample, three-quarters of participants reported having been exposed to at least one traumatic event (lifetime prevalence). In addition, 20% of the students had symptom levels above the clinical threshold for PTSD. Among exposed individuals, particularly females, higher levels of symptomatology in the first semester of the first academic year were associated with an increased likelihood of interrupting their studies before the end of the second academic year. The relationship between the two variables was partially explained by the cumulative grade point average in the first year, suggesting an effect of symptoms on learning ability.

Some studies have examined the effects of trauma in low- and middle-income countries. A study in Sri Lanka (Elbert et al. 2009) measured the effects of traumatic experiences, PTSD and depression on school performance and social integration in a sample of 420 school children. The results showed that 92% of the children had experienced potentially traumatic events (fighting, bombing and death of a relative) and that 25% met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. In addition, the results showed that the trauma caused long-term interference in the children’s daily lives, manifested in a decrease in academic performance and social withdrawal. Finally, there was shown to be a linear relationship: the more traumatic events the children were exposed to, the greater the effects on general functioning, both academic and social. This study shows the cumulative effect of trauma and highlights the importance of implementing psychosocial programs in post-conflict areas to try to reduce the negative consequences.

The studies reported here represent only a sample of the studies in the literature. Many others reach similar conclusions (Saigh et al. 1997; Berthold 2000; Hurt et al. 2001; Delaney-Black et al. 2002; Henrich et al. 2004; Daignault and Hebert 2009; Goodman et al. 2012; Hardner et al. 2018). We invite the reader to read the literature review by Perfect et al. (2016), which lists many studies that have shown the negative impact of trauma on learning.

8.4. Trauma and learning: cognitive intermediaries

Among the various factors that may explain the negative relationship between traumatic exposure and learning, factors related to cognitive health are of primary importance. By cognitive health, we mean the efficiency of various cognitive functions, such as reasoning and memory, which are involved in the process of acquiring new knowledge and skills. Over the past 30 years, numerous studies have shown that exposure to trauma has a negative impact on several cognitive dimensions (see Scott et al. (2015) for a meta-analysis of the impact of trauma on nueor-cognitive functioning.). Links have been documented with short-term (or working) memory, long-term memory, reasoning and attention. We can postulate that these cognitive effects explain the negative effects of trauma on learning. To our knowledge, such a mediating effect has rarely been studied directly (see, however, Ogata (2017) who suggest such a link) and thus represents an interesting avenue for future research.

Studies of the cognitive correlates of trauma have often focused on a psychopathological explanation: trauma generates pathologies (PTSD, depression), and it is the emergence of these pathologies that affects cognitive functioning. This idea of trauma having an indirect effect – which largely dominates the literature on the subject – has been demonstrated; the link between psychopathology and cognitive health is widely documented (Tapia et al. 2007). More recently, some authors have also put forward the idea of a direct effect of trauma, independent of psychopathology (Blanchette et al. 2019). This hypothesis of a direct effect is important, since a good proportion of individuals exposed to a traumatic event does not develop symptoms at a clinically significant level. It is possible that trauma affects cognitive health even in the absence of pathology. The literature evaluating this hypothesis is scarce and, to our knowledge, mainly concerns the issue of memory (see section 8.4.1). This hypothesis should be evaluated more systematically in future studies.

8.4.1. Short-term memory or working memory

In this section, we consider several studies on the links between traumatic exposure and short-term memory (Blanchette and Caparos 2016; Blanchette et al. 2019). Short-term memory is typically assessed using tasks that require the maintenance of activation of a given amount of information over a short period. For example, participants hear a sequence of consonants or numbers and are asked to repeat the sequence, as heard. This is referred to as a classical span task.

Since the 1970s, short-term memory has not been conceived of as a simple storage space (Baddeley and Hitch 1974): it is rather conceptualized as a set of structures allowing not only for information to be kept active, but also for this information to be manipulated and transformed. To account for this memory system’s active role, we use the term working memory. In cognitive psychology and neuropsychology, the functioning of working memory is evaluated using tasks that require both the maintenance of a given piece of information for a short period of time and the manipulation of this information. An example is the reverse span task, in which a sequence of information presented to the participant must be repeated in reverse (participants hear “7, 4, 5” and must produce the response “5, 4, 7”).

Short-term information retention, with or without associated manipulation, is essential for the proper functioning of high-level cognitive operations such as reasoning, language comprehension, decision-making and the encoding of information in long-term memory. Because of this central role in complex cognition, difficulties with short-term and working memory will have a significant impact on an individual’s ability to learn.

The first study we report here focused on victims of sexual violence. The study population consisted of a sample of female Québécois undergraduate psychology students. In the sample of students (recruited from the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières), half reported exposure to sexual violence (ranging from non-consensual touching to rape). We were interested in the relationship between the severity of the sexual abuse reported by the participants and their short-term memory capacity. In this study, we also measured the impact of moderate stress from daily experiences on memory, which we call “lifetime stress” (see Box 8.2).

The results of the study showed that participants reporting experiences of sexual violence had on average poorer performance on short-term memory tasks compared to those unexposed. In addition, short-term memory was also negatively correlated with stressful life experiences. These results support the existence of a sizeable link between short-term memory and exposure to trauma and stress (see Table 8.1). Furthermore, the results showed that this link existed even when PTSD symptoms were excluded, suggesting that trauma exposure as such may have cognitive correlates, independent of psychopathological symptoms.

Box 8.2. Lifetime stress

Table 8.1. Correlations between performance on a short-term memory task, severity of sexual violence and lifetime stress reported by Quebec participants (Blanchette and Caparos 2016). The table presents r values (Pearson correlations), which represent the strength of the relationship between two contiguous variables. N is the number of participants included in the analysis. * Significant at p < 0.05, ** significant at p < 0.01

| Short-term memory performance | Severity of sexual violence | Lifetime stress | |

| Severity of sexual abuse | r = −0.16* N = 228 | ||

| Lifetime stress | r = −0.27** N = 227 | r = 0.35** N = 230 | |

| PTSD | r = −0.08 N = 144 | r = 0.52** N = 145 | r = 0.40** N = 145 |

The question of the long-term relationship between trauma exposure and cognitive health has rarely been studied in non-Western contexts, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. These countries are particularly vulnerable to violence (due to political instability and armed conflict) and thus to trauma. This issue is important because the challenges of individual and societal reconstruction can be enormous, and this reconstruction partly relies on the cognitive resources of the populations.

Here we report the results of a study conducted on a sample of African participants exposed to an event with particularly high traumatic potential: the Rwandan genocide (Blanchette et al. 2019). Previous studies on political violence and cognitive health have focused on groups of refugees in Western countries. The experience of displacement can lead to stress in itself, which could potentiate cognitive deficits. It is important to study those exposed to violence who have not migrated to a Western country, as these represent the majority of affected civilians worldwide. Furthermore, there are relatively few studies on cognitive functioning in African samples and none, to our knowledge, specifically examining the cognitive consequences of exposure to political violence.

The results of this study showed that the higher the participants’ PTSD symptoms were, the worse their performance on the short-term memory task. Furthermore, the degree of exposure to the Rwandan genocide was also negatively related to short-term memory performance (see Figure 8.3). These results are consistent with previous findings in other samples, including samples of war veterans and individuals exposed to natural disasters (Navalta et al. 2006; Hart et al. 2008; Cherry et al. 2010). On the other hand, data showed that trauma exposure itself was associated with a decrease in short-term memory performance, even after controlling for the effect attributable to PTSD symptoms. It is possible that the effects of trauma on short-term memory are explained in part by an effect on attention and executive functions. We discuss the impact of trauma on these two dimensions in sections 8.3.3 and 8.3.4.

Short-term and working memory play a very important role in learning and academic performance (Vock et al. 2011). It is necessary to consider the negative effects of traumatic exposure on these cognitive mechanisms in learners. The example of young migrants from sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East who have arrived in Europe in recent years in large numbers following journeys fraught with violent experiences will be given here. Once in Europe, these migrants have to learn a new language and acquire new habits in order to integrate into their host country. Short-term memory difficulties can be a major barrier to this learning process. Another barrier is long-term memory difficulties, which we discuss next.

Figure 8.3. Relationship between genocide exposure and short-term memory in a sample of Rwandan participants. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/habib/emotional.zip

8.4.2. Long-term memory

One of the primary objectives of learning is to allow the recording in long-term memory of new knowledge of a semantic nature (e.g. when learning to drive, one must know the rules of the road), or know-how, of a procedural nature (e.g. being able to handle a car). This information will need to be retrievable at appropriate times. Although recording memories of an episodic nature is not the primary goal of the learner, several results in the literature show that, in the early stages of learning, the ability to retrieve semantic or procedural information is strongly linked to the ability to reactivate episodic memories (Herbert and Burt 2004; Beaunieux et al. 2006).

When asked to access an autobiographical memory stored in long-term memory, a person is usually able to recall an event that took place at a specific time on a specific day and to provide details about the context of the event. The activation of such an autobiographical memory is usually associated with a reactivation of certain sensory and affective aspects related to the event (e.g. things seen and heard at the time of the event and affects that were felt). The ability to reactivate episodic memories is an important predictor of learning ability (Herbert and Burt 2004; Beaunieux et al. 2006). In other words, learning relies heavily – in its initial phase – on autobiographical memory and on the ability to reactivate learning contexts. Several results in the literature show that this capacity is impaired in PTSD and depression.

Specifically, studies show that people with PTSD and/or depression have more difficulty recalling events related to a specific occasion in time and space (Williams et al. 2007). They tend to retrieve general memories, which are a kind of “summary” of an event over several days, or a generic class of events that occurred several times. This phenomenon is called “overgeneral memory”. When Rwandan participants were asked to report a specific memory related to the 1994 genocide, some were able to report a specific memory (e.g. “near my grandfather’s house, less than a kilometer away, they burned a church. There were between 200 and 400 people inside. I was in the house and I could see the flames”), while others reported a non-specific and overgeneral memory (e.g. “during the genocide, there was one ethnic group killing the other ethnic group”).

An evaluative review of 24 studies concluded that psychopathological symptoms related to depression and PTSD are strongly associated with overgeneral memory (Moore and Zoellner 2007). In addition, a recent meta-analysis including 13 studies on trauma suggests that there is also a sizeable association between exposure to trauma per se – independent of PTSD – and overgeneral memory (Ono et al. 2016). This meta-analysis also concludes that this effect is exacerbated by PTSD.

Williams et al. (2007) locate the origin of overgeneral memory in affective regulation. They suggested that overgeneral memory is the result of an attempt to avoid trauma-related thoughts in order to alleviate distress. This style of thinking generalizes to other memories and non-trauma-related thoughts and produces an “overgeneralizing” cognitive style, which would explain why overgeneral memory is observed for all types of memories – negative, neutral and positive – not just trauma-related memories.

Indeed, results suggest that there is a strong link between overgeneral memory and cognitive avoidance strategies, at least in PTSD (Sumner 2012). When learning, overgeneral memory prevents the reactivation of the context surrounding the initial processing of information (Raes et al. 2006) and thus decreases the long-term integration of the information learned. This could explain the numerous results showing difficulties in retrieving information stored in long-term memory in people suffering from PTSD.

PTSD is associated not only with overgeneral memory, but also with another cognitive process related to memory and particularly important to the proper functioning of the individual: future thinking.

Brown et al. (2013) studied veterans returning from Iraq with and without PTSD. They asked them to (1) retrieve recent (last month) or distant (5–20 years) memories in response to neutral verbal cues and (2) imagine future experiences close (next month) or distant (5–20 years) in time, also based on neutral cues. In all categories, veterans with PTSD were less specific than other participants. Similarly, Kleim et al. (2014) recruited survivors of assault and vehicular accidents, with and without PTSD. Participants were asked to produce and describe future personal events in response to negative and positive cues. PTSD was associated with overgeneral future thoughts, especially for positive words.

The link between PTSD, overgeneral memory and future thinking is consistent with the idea that there is significant overlap between episodic memory and other cognitive processes, such as imagining possibilities. The mechanism of future thinking is important to the individual, particularly because it is related to the anticipation of rewards in response to an action. Engaging in a learning process typically involves the investment of large amounts of cognitive resources, motivated by the anticipation of future benefits. Difficulty in projecting into the future could therefore have a negative impact on motivation and on the desire to invest in a learning task (see section 8.4.5 which takes up this argument, in relation to depression). This effect could account, in part, for the negative link between trauma and learning.

8.4.3. Reasoning

Beyond memory, several high-level cognitive mechanisms play an important role in learning, including reasoning. Induction is an important form of reasoning for learning, as it allows us to generate a rule or law based on observations and experiences. Deduction is another form of reasoning that is important for learning, as it allows us to create links between concepts, through a process of association, in order to make sense of them.

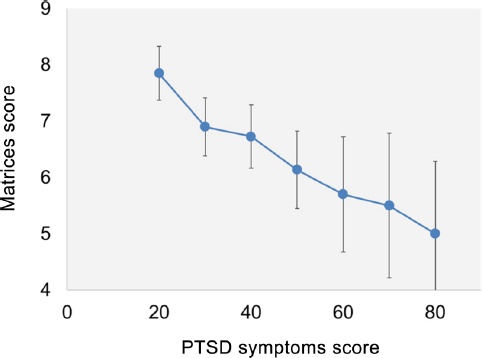

Figure 8.4. Relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and abstract reasoning score (WAIS matrices) in a sample of Rwandan participants. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/habib/emotional.zip

Because reasoning relies on the efficiency of other cognitive mechanisms, such as short-term memory (Vock et al. 2011), poorer logical performance can be predicted in individuals exposed to trauma. To our knowledge, very few studies have directly assessed this hypothesis. We tested this in a sample of Rwandan participants (discussed in section 8.4.1) (Caparos et al. 2017). Participants performed several different reasoning tasks. We observed that exposure to the Rwandan genocide was negatively correlated with performance on a conditional reasoning task, r(220) = −0.120, p = 0.074, and with performance on a transitive reasoning task, r(162) = −0.157, p = 0.045. These negative relationships were observed even when controlling for symptoms of PTSD and depression, suggesting an effect of traumatic exposure that is partly independent of symptoms. However, the latter is also likely to have a significant effect, as shown by the relationship between PTSD symptoms and performance on the WAIS matrix task among Rwandan participants (r(154) = −0.212, p = 0.008, see Figure 8.4) (Caparos et al. 2017).

8.4.4. Executive functions

The impact of trauma on reasoning and memory (short and long term) could be explained by an effect on executive functions (Miyake et al. 2000). Executive functions can be defined as the cognitive processes that control and regulate other cognitive activities (see reminder below). Executive functions have an important role to play in the selection of information to be processed (selective attention), in the encoding and retrieval of this information (memory) and in the manipulation of information for meaning extraction (reasoning). Executive functions, and in particular flexibility, are crucial for finding and learning creative solutions to problems.

DePrince et al. (2009) studied 110 children whose parents completed a questionnaire measuring exposure to potentially traumatic events related, or not, to the family context. These children completed a battery of tests measuring different aspects of executive functions (speed of information processing, flexibility and inhibition of distractors). Exposure to trauma, and more specifically to trauma in a family setting, was associated with a general decline in executive function performance. This effect was maintained after controlling for the children’s anxiety, socio-economic status and the possible presence of traumatic brain damage. The authors suggest that these executive deficits may explain, at least in part, why maltreated children are at greater risk of instability in their social relationships, behavioral problems and academic difficulties. Numerous studies have shown that trauma-related affective disorders – depression and PTSD – are associated with executive deficits (Tapia et al. 2007) and that these are likely to impact memory and reasoning. For example, in a series of experiments, Dalgleish et al. (2007) showed that verbal fluency – an indirect measure of executive function – mediates the relationship between depression and overgeneral memory. Alterations in cognitive control, necessary for the implementation of effective memory retrieval strategies, are thus responsible for overgeneral memory.

8.4.5. Sustained attention

Psychopathological symptoms resulting from traumatic exposure are likely to have a significant impact on attention, and more specifically on sustained attention. When learning, it is necessary to concentrate large amounts of cognitive resources for prolonged periods of time. This concentration of resources is made possible by a mechanism known as sustained attention. If sustained attention is deficient, the information will be processed less well and the entire cognitive chain will be affected.

PTSD can affect sustained attention through its effect on sleep. Indeed, people with PTSD frequently experience difficulty falling asleep and dull sleep. This sleep disorder leads to high irritability, angry outbursts and agitation during waking periods (see also section 8.5.1). These symptoms of hypervigilance are associated with significant difficulties in concentration (Tapia et al. 2007).

Depression is also likely to affect sustained attention through its effect on motivation. A fundamental characteristic of the depressed state is difficulty in experiencing positive affects. This has a direct impact on the motivation a person will have to engage in everyday activities. Before undertaking an action that requires effort (physical or mental) and committing resources, we contrast the benefits and costs associated with that action. The benefits are the rewards associated with the action. In the case of learning, these are often long-term rewards, linked to an increase in the individual’s autonomy and to an improvement of their prospects (e.g. employment and social integration, which are made possible by intellectual skills such as reading, mathematics and foreign languages, and also by skills such as driving, cooking and DIY). The cost is the cognitive energy required to acquire any new skill.

In depression, there is a reduction in sensitivity to rewards (the benefit) and an increase in sensitivity to effort (the cost). This effect, directly related to the neural networks involved in motivation (Sherdell et al. 2012), may explain why depressed individuals experience difficulties in focusing and maintaining attention (Egeland et al. 2003; Van Der Meere et al. 2007). It is therefore possible that depressive symptoms resulting from traumatic experience negatively affect learning abilities through their impact on motivation and sustained attention.

8.5. Neuroanatomical and physiological considerations

8.5.1. Physiological arousal

The sleep difficulties observed in individuals exposed to traumatic events, especially those suffering from PTSD, are likely to be related to a dysregulation of physiological arousal (Aston-Jones and Cohen 2005). Many results have shown that physiological arousal is a predictor of cognitive functioning (Manly et al. 2005). When physiological arousal is too low, for example in states of fatigue and drowsiness, the availability of cognitive resources decreases, making it more difficult for the individual to focus their attention on the information being processed. Many cognitive mechanisms are then affected, such as memory and reasoning abilities.

At the other extreme, in certain situations, and particularly in the case of PTSD, the individual experiences an excess of physiological activation. This is called hyperarousal or hypervigilance. It is possible that this excess activation results from a dysfunction of the Limbic-Hypothalamic-Pituitary Adrenal Axis (or LHPA). The LHPA assesses stressors and regulates the neurochemical responses that accompany them. Several studies suggest that prolonged exposure to acute stress, during a traumatic event for example, may impair the ability of this system to regulate stress responses (De Bellis and Thomas 2003; De Bellis and Zisk 2014; Davis et al. 2015). Like the state of physiological hypoactivation, hyperactivation is detrimental to cognitive functioning. It prevents the individual from focusing attention on a given task and decreases the ability to inhibit and filter irrelevant information (Lanius et al. 2001).

Figure 8.5. Relationship between physiological arousal and cognitive performance

8.5.2. The hippocampus

The hippocampus is an anatomical structure that plays a very important role in memory processes and, more generally, in learning processes (Zola-Morgan and Squire 1990). It is part of the limbic system and is located in the temporal lobe. Numerous studies have shown that lesions in the hippocampus lead to profound memory deficits, particularly anterograde amnesia (Scoville and Milner 1957).

It is possible that a reduction in hippocampal size is one of the neuroanatomical correlates of some of the memory deficits observed in PTSD. Indeed, several neuroimaging studies, which compared traumatized subjects with PTSD, traumatized subjects without PTSD and control subjects, showed a reduction in hippocampal volume in the PTSD group (Bremner et al. 1997; Villareal et al. 2002; Winter and Irle 2004). Such a reduction of the hippocampus could therefore explain the memory problems found in PTSD sufferers.

8.6. Conclusion

Figure 8.6. Model to explain the negative effects of trauma on learning. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/habib/emotional.zip

The studies presented in this chapter show that an individual’s traumatic history is likely to have an impact on different dimensions of cognitive and neurophysiological functioning, and that these effects may explain the negative impact of trauma on learning (see Figure 8.6 for a summary). In a 2016 study of a sample of 400 children from four Californian schools, a quarter of the children reported experiencing at least one potentially traumatic event (Gonzalez et al. 2016), and, of those exposed, three-quarters showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress. These high levels of exposure and symptoms indicate that trauma and its consequences are significant factors to address in order to reduce academic failure. Results from the literature suggest that psychotherapeutic treatment can improve the learning of children exposed to violence (Layne et al. 2001). It is urgent to take into account this data, which has been documented for several decades now, in order to improve the prospects for the development of all individuals.

8.7. References

American Psychiatric Association (2015). DSM-5-Manuel diagnostique et statistique des troubles mentaux. Elsevier Masson, Issy-les-Moulineaux.

Amstadter, A.B. and Vernon, L.L. (2008). Emotional reactions during and after trauma: A comparison of trauma types. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 16, 391–408. doi.org/10.1080/10926770801926492.

Aston-Jones, G. and Cohen, J.D. (2005). An integrative theory of locus-coeruleusnorepinephrine function: Adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, 403–450. doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709.

Baddeley, A.D. and Hitch, G.J. (1974). Working memory. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Bower, G.H. (ed.). Academic Press, New York.

Beaunieux, H., Hubert, V., Witkowski, T., Pitel, A.L., Rossi, S., Danion, J.M., Desgranges, B., Eustache, F. (2006). Which processes are involved in cognitive procedural learning? Memory, 14, 521–553. doi.org/10.1080/09658210500477766.

Berthold, S.M. (2000). War traumas and community violence: Psychological, behavioral, and academic outcomes among Khmer refugee adolescents. Journal of Multi-cultural Social Work, 8, 15–46. doi.org/10.1300/J285v08n01_02.

Blanchette, I. and Caparos, S. (2016). Working memory function is linked to trauma exposure, independently of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 21, 494–509. doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2016.1236015.

Blanchette, I., Rutembesa, E., Habimana, E., Caparos, S. (2019). Long-term cognitive correlates of exposure to trauma: Evidence from Rwanda. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11, 147–155. doi.org/10.1037/tra0000388.

Bowen, N. and Bowen, G. (1999). Effects of crime and violence in neighborhoods and schools on the school behavior and performance of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 319–342. doi.org/10.1177/0743558499143003.

Boyraz, G., Horne, S.G., Owens, A.C., Armstrong, A.P. (2013). Academic achievement and college persistence of African American students with trauma exposure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 582–592. doi.org/10.1037/a0033672.

Bremner, J.D., Randall, P., Scott, T.M., Vermetten, E., Staib, L., Bronen, R.A., Mazure, C., Capelli, S., McCarthy, G., Innis, R.B., Charney, D.S. (1997). Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse – A preliminary report. Biological Psychiatry, 41, 23–32. doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00162-X.

Breslau, N. (2009). The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10, 198–210. doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334448.

Brown, A.D., Root, J.C., Romano, T.A., Chang, L.J., Bryant, R.A., Hirst, W. (2013). Overgeneralized autobiographical memory and future thinking in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 129–134. doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.11.004.

Caparos, S., Rutembesa, E., Habimana, E., Blanchette, I. (2017). Impact de l’exposition traumatique sur le fonctionnement cognitif. Colloque International “Du Trauma à la Reconstruction”, Kigali.

Cherry, K.E., Galea, S., Su, L.J., Welsh, D.A., Jazwinski, S.M., Silva, J.L., Erwin, M.J. (2010). Cognitive and psychosocial consequences of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita among middle-aged, older, and oldest-old adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS). Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 2463–2487. doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00666.x.

Conte, J. and Schuerman, J. (1987). The effects of sexual abuse on children: A multidimensional view. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 4, 204–219. doi.org/10.1177/0886260587 00200404.

Daignault, I.V. and Hebert, M. (2009). Profiles of school adaptation: Social, behavioral, and academic functioning in sexually abused girls. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33, 102–115. doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.06.001.

Dalgleish, T., Williams, J.M.G., Golden, A.M.J., Perkins, N., Barrett, L.F., Barnard, P.J., Watkins, E. (2007). Reduced specificity of autobiographical memory and depression: The role of executive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 23–42. dx.doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.23.

Davis, A.S., Moss, L.E., Nogin, M.M., Webb, N.E. (2015). Neuropsychology of child maltreatment and implications for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 77–91. doi.org/10.1002/pits.21806.

De Bellis, M.D. and Thomas, L.A. (2003). Biologic findings of posttraumatic stress disorder and child maltreatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 5, 108–117. doi.org/10.1007/s11920-003-0027-z.

De Bellis, M.D. and Zisk, A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 23, 185–222. doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002.

Delaney-Black, V., Covington, C., Ondersma, S.J., Nordstrom-Klee, B., Templin, T., Ager, J., Sokol, R.J. (2002). Violence exposure, trauma, and IQ and/or reading deficits among urban children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156, 280–285. doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.3.280.

DePrince, A.P., Weinzierl, K.M., Combs, M.D. (2009). Executive function performance and trauma exposure in a community sample of children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 353–361. doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.08.002.

Duplechain, R., Reigner, R., Packard, A. (2008). Striking differences: The impact of moderate and high trauma on reading achievement. Reading Psychology, 29, 117–136. doi.org/10. 1080/02702710801963845.

Dyson, J. (1990). The effect of family violence on children’s academic performance and behavior. Journal of the National Medical Association, 82, 17–22 [Online]. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2625936/.

Egeland, J., Rund, B.R., Sundet, K., Landrø, N.I., Asbjørnsen, A., Lund, A., Hugdahl, K. (2003). Attention profile in schizophrenia compared with depression: Differential effects of processing speed, selective attention and vigilance. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108, 276–284. doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00146.x.

Elbert, T., Schauer, M., Schauer, E., Huschka, B., Hirth, M., Neuner, F. (2009). Trauma-related impairment in children – A survey in Sri Lankan provinces affected by armed conflict. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 238–246. doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.008.

Evans, J.S.B.T. (2011). Dual-process theories of reasoning: Contemporary issues and developmental applications. Developmental Review, 31, 86–102. doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2011. 07.007.

Friedman, N.P., Miyake, A., Young, S.E., DeFries, J.C., Corley, R.P., Hewitt, J.K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137, 201–225. doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201.

Gonzalez, A., Monzon, N., Solis, D., Jaycox, L., Langley, A.K. (2016). Trauma exposure in elementary school children: Description of screening procedures, level of exposure, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. School Mental Health, 8, 77–88. doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9167-7.

Goodman, R.D., Miller, M.D., West-Olatunji, C.A. (2012). Traumatic stress, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement among primary school students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 252–259. doi.org/10.1037/a0024912.

Hardner, K., Wolf, M.R., Rinfrette, E.S. (2018). Examining the relationship between higher educational attainment, trauma symptoms, and internalizing behaviors in child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 375–383. doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.007.

Hart, J., Kimbrell, T., Fauver, P., Cherry, B.J., Pitcock, J., Booe, L.Q., Freeman, T.W. (2008). Cognitive dysfunctions associated with PTSD: Evidence from World War II prisoners of war. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 20, 309–316. doi.org/10. 1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.309.

Henrich, C.C., Schwab-Stone, M., Fanti, K., Jones, S.M., Ruchkin, V. (2004). The association of community violence exposure with middle-school achievement: A prospective study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25, 327–348. doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev. 2004.04.004.

Herbert, D.M. and Burt, J.S. (2004). What do students remember? Episodic memory and the development of schematization. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 18, 77–88. doi.org/10.1002/acp. 947.

Hurt, H., Malmud, E., Brodsky, N.L., Giannetta, J. (2001). Exposure to violence: Psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archival of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 155, 1351–1356. doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1351.

Kleim, B., Graham, B., Fihosy, S., Stott, R., Ehlers, A. (2014). Reduced specificity in episodic future thinking in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 165–173. doi.org/10.1177/2167702613495199.

Klein, K. and Boals, A. (2001). The relationship of life event stress and working memory capacity. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, 565–579. doi.org/10.1002/acp.727.

Lanius, R.A., Williamson, P.C., Densmore, M., Boksman, K., Gupta, M.A., Neufeld, R.W., Menon, R.S. (2001). Neural correlates of traumatic memories in posttraumatic stress disorder: A functional MRI investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1920–1922. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1920.

Larson, S., Chapman, S., Spetz, J., Brindis, C.D. (2017). Chronic childhood trauma, mental health, academic achievement, and school-based health center mental health services. Journal of School Health, 87, 675–686. doi.org/10.1111/josh.12541.

Layne, C.M., Pynoos, R.S., Saltzman, W.R., Arslanagić, B., Black, M., Savjak, N., Popović, T., Duraković, E., Mušić, M., Ćampara, N., Djapo, N., Houston, R. (2001). Trauma/grief-focused group psychotherapy: School-based postwar intervention with traumatized Bosnian adolescents. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5, 277–290. doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.5.4.277.

Lipschitz, D., Rasmusson, A., Anyan, W., Cromwell, P., Southwick, S. (2000). Clinical and functional correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder in urban adolescent girls at a primary care clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1104–1111. doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200009000-00009.

Manly, T., Dobler, V.B., Dodds, C.M., George, M.A. (2005). Rightward shift in spatial awareness with declining alertness. Neuropsychologia, 43, 1721–1728. doi.org/10.1016/j. neuropsychologia.2005.02.009.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N., Emerson, M., Witzki, A., Wager, T. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49–100. doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0734.

Moore, S.A. and Zoellner, L.A. (2007). Overgeneral autobiographical memory and traumatic events: An evaluative review. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 419–437. doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.419.

Moors, A., Ellsworth, P.C., Scherer, K.R., Frijda, N.H. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5, 119–124. doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165.

Munyandamutsa, N., Mahoro Nkubamugisha, P., Gex-Fabry, M., Eytan, A. (2012). Mental and physical health in Rwanda 14 years after the genocide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1753–1761. dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0494-9.

Navalta, C.P., Polcari, A., Webster, D.M., Boghossian, A., Teicher, M.H. (2006). Effects of childhood sexual abuse on neuropsychological and cognitive function in college women. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 18, 45–53. doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.18.1.45.

Ogata, K. (2017). Maltreatment related trauma symptoms affect academic achievement through cognitive functioning: A preliminary examination in Japan. Journal of Intelligence, 5, 32–39. doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence5040032.

Ono, M., Devilly, G.J., Shum, D.H.K. (2016). A meta-analytic review of overgeneral memory: The role of trauma history, mood, and the presence of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 157–164. doi.org/10. 1037/tra0000027.

Perfect, M.M., Turley, M.R., Carlson, J.S., Yohanna, J., Saint Gilles, M.P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8, 7–43. doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2.

Porche, M.V., Fortuna, L.R., Lin, J., Alegria, M. (2011). Childhood trauma and psychiatric disorders as correlates of school dropout in a national sample of young adults. Child Development, 82, 982–998. doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01534.x.

Pynoos, R., Fredrick, C., Nader, K., Arroyo, W., Steinberg, A., Eth, A., Nunez, F., Fairbanks, L. (1987). Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Archives of General Psychology, 44, 1057–1063. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005.

Race, E., Keane, M.M., Verfaellie, M. (2011). Medial temporal lobe damage causes deficits in episodic memory and episodic future thinking not attributable to deficits in narrative construction. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 10262–10269. doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI. 1145-11.2011.

Raes, F., Hermans, D., Williams, J.M.G., Demyttenaere, K., Sabbe, B., Pieters, G., Eelen, P. (2006). Is overgeneral autobiographical memory an isolated memory phenomenon in major depression? Memory, 14, 584–594. doi.org/10.1080/09658210600624614.

Rytwinski, N.K., Scur, M.D., Feeny, N.C., Youngstrom, E.A. (2013). The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 299–309. doi.org/10.1002/jts.21814.

Saigh, P.A., Mroueh, M., Bremner, J.D. (1997). Scholastic impairments among traumatized adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 429–436. doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967 (96)00111-8.

Salzinger, S., Kaplan, S., Pelcovitz, D., Samit, C., Krieger, R. (1984). Parent and teacher assessment of children’s behavior in child maltreating families. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23, 458–464. doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60325-3.

Scherer, K.R. (2001). Appraisal considered as a process of multilevel sequential checking. In Series in Affective Science. Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research, Scherer, K.R., Schorr, A., Johnstone, T. (eds). Oxford University Press, New York.

Schnyder, U. (2005). Psychothérapies pour les PTSD – une vue d’ensemble. Psychothérapies, 25, 39–52. doi.org/10.3917/psys.051.0039.

Schwab-Stone, M., Ayers, T., Kasprow, W., Voyce, C., Barone, C., Shriver, T. (1995). No safe haven: A study of violence exposure in an urban community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1343–1352. doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199510000-00020.

Scott, J.C., Matt, G.E., Wrocklage, K.M., Crnich, C., Jordan, J., Southwick, S.M., Schweinsburg, B.C. (2015). A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 14(1), 105–140. doi:10.1037/a0038039.

Scoville, W.B. and Milner, B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 20, 11–21. doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11.

Shanok, R., Welton, S., Lapidus, C. (1989). Group therapy for preschool children: A transdisciplinary school-based program. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 6, 72–95. doi.org/10.1007/BF00755712.

Sherdell, L., Waugh, C.E., Gotlib, I.H. (2012). Anticipatory pleasure predicts motivation for reward in major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 51–60. doi.org/10.1037/a0024945.

Sliwinski, M.J., Smyth, J.M., Hofer, S.M., Stawski, R.S. (2006). Intraindividual coupling of daily stress and cognition. Psychology and Aging, 21, 545–557. doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.545.

Stawski, R.S., Sliwinski, M.J., Smyth, J.M. (2006). Stress-related cognitive interference predicts cognitive function in old age. Psychology and Aging, 21, 535–544. doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.535.

Suliman, S., Mkabile, S.G., Fincham, D.S., Ahmed, R., Stein, D.J., Seedat, S. (2009). Cumulative effect of multiple trauma on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50, 121–127. doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.006.

Sumner, J.A. (2012). The mechanisms underlying overgeneral autobiographical memory: An evaluative review of evidence for the CaR-FA-X model. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 34–48. doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.10.003.

Tapia, G., Clarys, D., El-Hage, W., Isingrini, M. (2007). Les troubles cognitifs dans le Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) : une revue de la littérature. L’Année psychologique, 107, 489–523. doi.org/10.3917/psys.051.0039.

Van Der Meere, J., Börger, N., Van Os, T. (2007). Sustained attention in major unipolar depression. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 104, 1350–1354. doi.org/10.2466/pms.104.4.1350-1354.

Villareal, G., Hamilton, D.A., Petropoulos, H., Driscoll, I., Rowland, L.M., Grieco, J.A, Kodituwakku, P.W., Hart, B.L., Escola, R., Brooks, W.M. (2002). Reduced hippocampal volume and total white matter volume reduction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 119–125. doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01359-8.

Vock, M., Preckel, F., Holling, H. (2011). Mental abilities and school achievement: A test of a mediation hypothesis. Intelligence, 39, 357–369. doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2011.06.006.

Williams, J.M.G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 122–148. doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122.

Winter, H. and Irle, E. (2004). Hippocampal volume in adult burn patients with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2114–2200. doi.org/10. 1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2194.

Zimrin, H. (1986). A profile of survival. Child Abuse and Neglect, 10, 339–349. doi.org/10. 1016/0145-2134(86)90009-8.

Zola-Morgan, S.M. and Squire, L.R. (1990). The primate hippocampal formation: Evidence for a time-limited role in memory storage. Science, 250, 288–290. doi.org/10.1126/science. 2218534.