Chapter Four

Four Steps of Preparation

Case Studies: William Henry Seward • The Kennedy–Nixon Debate Revisited • Alan Schroeder • Don Hewitt, CBS • Robert Bork • Supreme Court Murder Boards • Garry Wills • William Safire • Rachel Brand • Marcus Tullius Cicero

There are very few men in the world who can make a good speech without any previous thought or preparation whatever. They may say smart things, and put them together in a pleasant way, but if the subject is of any importance, they cannot greatly enlighten or instruct an audience without thinking about it and studying it themselves.1

The New York Times

September 20, 1851

The observation in the epigraph was about a speech made by William Henry Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State in Abraham Lincoln’s administration. Seward’s approach to preparation is even more important in Q&A because, in the free-fire zone of such sessions, a presenter can lose control. To avoid that fate, you must prepare diligently, following these steps:

Research. Learn the background of your audience.

Anticipate. Assemble a list of tough questions your audience might ask.

Distill. Find the main themes in all the questions.

Prepare Your Position. Develop and decide your response the main themes.

■ Research ■

As any responsible businessperson would do for any business project, do your homework. Gather as much information as you can about your audience. Visit their website for current information, find their issues, concerns, and hot buttons. Search the web for related information. Assemble a briefing book.

Research in Action

In preparation for the landmark Kennedy–Nixon debate, each of the candidates’ teams “compiled massive briefing books,” according to Professor Alan Schroeder of Northeastern University’s School of Journalism. But, as he chronicled in his book Presidential Debates, there were stark differences between how each of the men applied the research:

JFK’s people called theirs the “Nixopedia”—only Kennedy bothered to practice for the debate with his advisors…[his] predebate preps consisted of informal drills with aides reading questions off index cards.

According to Nixon campaign manager Bob Finch, “We kept pushing for [Nixon] to have some give-and-take with either somebody from the staff…anything. He hadn’t done anything except to tell me he knew how to debate. He totally refused to prepare.”2

Kennedy and Nixon also differed in how they prepared for the first live televised debate.

Don Hewitt, who went on to become the driving force behind CBS’s 60 Minutes, was the television director of the debate. In his autobiography Tell Me a Story, Hewitt described the behind-the-scenes preparation factors: Kennedy arrived in Chicago three days before the debate to rehearse and rest. Nixon, who was fighting a viral infection, continued to campaign vigorously right up to the day of the debate. By the time he arrived at the WBBM-TV studios, he was exhausted and underweight, and his suit looked a size too big for his thin frame.

The Kennedy team had surveyed the studio in advance and advised him to wear a dark suit to contrast with the light blue cyclorama that served as the backdrop for the set, a staple in those days of black-and-white television. Nixon wore a light gray suit that translated into the same monochrome value, so he blended into the background and appeared pallid (refer to Figure 1.1).3

All these factors, along with the candidates’ differentiated responses to questions, created a shift in the public opinion polls and, ultimately, the votes. Everything counts.

From that moment on, media consultants have been as important as positioning strategists in political campaigns, and preparation has become an absolute imperative for debates. In every election, every candidate ramps up for each debate with the thoroughness of the Allies planning for D-Day.

Follow the example of the JFK team and their “Nixopedia” briefing books. The lessons of presidential debates apply to the dynamics of every other type of Q&A session, including every one of your own Q&A sessions.

■ Anticipate ■

Assemble a list of potential challenging questions. You know more about your own business and company than anyone else. Ask your colleagues for insights and potential questions. Solicit input from other resources beyond colleagues: customers, partners, consultants, and, if you can, even from your competitors. The CEO of an AI technology company told me that, in addition to the information about competitive positioning he finds on publicly available websites and on the competitors’ own websites, he speaks directly with some of his competitors. Taken together, all this information enables him to anticipate a wide range of questions about competition from potential investors.

Prepare for the worst-case scenario. Make a list of the questions you dread hearing. Be thorough, be frank, be merciless. Gather the go-for-the-jugular questions. Plan for the war games.

Anticipate in Action

When President Ronald Reagan nominated Circuit Court Judge Robert Bork for the Supreme Court, it set off a battle royale with Democrats who viewed Bork as being too conservative. An aggressive campaign led by Senator Ted Kennedy (D–MA), succeeded in defeating the nomination in what came to be known as “Borking.”

But the defeat was also due in large part to Judge Bork’s preparation—or lack thereof. Pulitzer Prize presidential historian Garry Wills described what happened:

The handlers of nominees usually submit them to “murder boards,” rehearsals of the kind of treatment expected from the confirming committee. Judge Scalia had undergone this ordeal, but he told Judge Bork that he did not have to rely on such coaching.…Bork felt no need to prepare for it. Confirmation was a matter of course.4

After the Bork experience, subsequent Supreme Court nominees took heed. As a matter of course, they now engage in those “murder boards,” mock practice sessions that include everything from re-creating the physical arrangement of the senate chamber to anticipating the worst-case questions from the senators.

To distinguish murder boards from “moot court,” the law school simulation familiar to all attorneys, former presidential speechwriter and New York Times columnist William Safire wrote:

A term was needed to describe a more hectic, hostile affair. Murder board is Pentagonese, though some say the phrase originated in the interrogation methods used by intelligence analysts seeking to establish a defector’s bona fides. The original meaning was “rigorous examination of a proposed program” or, more specifically and less bureaucratically, “a group charged with the responsibility to slam a candidate or proposer of an idea up against the wall with tough questioning.”5

Sounds just like the “blood sport” that Leslie Pfrang described in Chapter Two to characterize how she runs Q&A practice sessions for IPO roadshows.

When Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Associate Justice Samuel Alito were Supreme Court nominees, they went through murder boards in preparation for their confirmation hearings. Rachel Brand, now the chief legal officer at Walmart, who helped each of them, said that the purpose of the murder boards is to ask:

…tough questions, argumentative questions, annoying questions…in the nastiest conceivable way, over and over and over.6

In my many years in business, I have seen some very comprehensive lists of questions, particularly in preparation for IPO roadshows. CEOs and CFOs solicit questions from their companies’ different departments, as well as from the investment bankers, attorneys, auditors, and public relations and investment advisors. From these results, they aggregate a multi-list megalist of questions. With all good intentions, these many sources also develop a parallel list of direct answers to those questions in what is known as “Rude Q&A.”

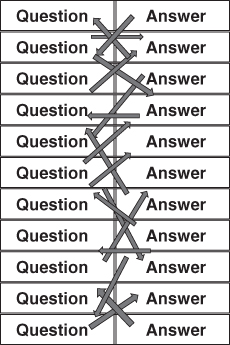

Unfortunately, there is a major problem with this approach: audiences do not ask questions as written but as long, random, nonlinear rambles. The presenter, then, suddenly on the hot spot as the focus of all the attention in the room, becomes stressed and frantically searches the two lists to find the part of the question that matches with the part of the answer (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 “Rude Q&A” Difficult to Match Questions with Answers

If you attempt to scuttle back and forth across the lists while under high pressure, you are sure to lose concentration and trip. You need a different approach. So, yes, do compile a list of potential challenging questions—but compile only the questions and not the answers.

■ Distill ■

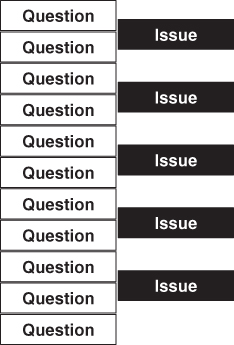

After you compile your list, look it over carefully. You’ll discover that, even if there are 100 tough questions, they fall into groups of only a handful of red flag issues (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Distill a Long List of Questions into a Handful of Red Flag Issues

To express the red flag issues succinctly, think of them as Roman Columns.

Roman Columns

If you’ve read the other books in this trilogy, you’re familiar with Roman Columns. For those of you who are not, it is a concept that goes back to the glory days of the Roman Empire, around 100 b.c.e., when the great Roman orators, such as Marcus Tullius Cicero, spoke in the Roman Forum for hours on end without notes. To remember what they wanted to say, the orators used the columns of the Forum as associative memory prompts. The tactic gave rise to what is today known as the Roman Room Technique,7 a method that helps people memorize lists of information. Under no circumstances, however, am I recommending that you memorize anything—neither your story nor your answers. For our purposes, consider the Roman Columns as distillation points for the key issues.

Seven Universal Issues

You won’t be surprised to discover that the red flag issues are the same in almost every industry. As a coach, I work with companies in IT, telecom, life sciences, finance, social media, real estate, retail, manufacturing, restaurants, and even the not-for-profit sector, and they all share the same Seven Universal Issues:

Price/Cost: “Too high?” “Too low?” “Too much?” “Too little?”

Compete/Differentiate: “How do you compete/differentiate?”

Qualifications/Capabilities: “Are you up to the task?”

Timing: “Too long?” “Too soon?”

Growth/Outlook: “How do you plan to get there from here?”

Contingencies: “What are you going to do if…?”

Problems: “What are your challenges?”

You also won’t be surprised know that, because these issues are so universal, teeing up an answer is greatly simplified. Please look back over the list and, this time, think about how you would answer those questions. Odds are that, even if you’ve only recently joined your company, you will have a general idea of the company’s position on every one of those issues.

After you’ve developed your list of questions and grouped them into categories, you will inevitably find related subjects that are unique to your industry or company. Some of these subjects are:

Go to Market

Product Strategy

Profitability

Market Size

Business Model

Add these subjects to the Universal Issues so that you can position your answers for each of them.

In Chapter Fifteen, as a culmination of all the skills you’re about to learn, you’ll see examples of how two different companies prepared for their IPO roadshows by developing positions for their answers to anticipated questions.

■ Prepare Your Position ■

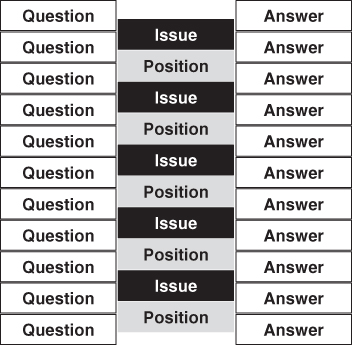

Having identified the red flag issues as they relate to your business, you can now develop a position to respond to each of them. For instance, if a question challenges your pricing as too high, your position is the rationale for your pricing. Start by writing the position as if you were writing a press release for the media. Here, too, discuss and consult with your colleagues. When you have arrived at a consensus, convert the issues into Key Word bullets. After that, it will then only be a matter of aligning the variation of the position bullets with the variation of the Universal Issues (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Develop a Position for Each Red Flag Issue

Do all your positioning during your preparation and not during your presentation. Do all your thinking in advance, not on your feet.

Now with your burden even further lightened, you are ready to match the variation of your answer to the variation of any question (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Match the Variation of the Question with a Variation of the Answer

You’ll learn more about answers in Chapter Twelve, but for now, if you have diligently followed these four steps of preparation, you are ready to Open the Floor to questions in the next chapter.