Chapter Ten

Buy (Thinking) Time with Buffers

Case Studies: Harald Krueger, BMW • Eric Yuan, Zoom Video Communications • Colin Powell • Ronald Hall • Andy Kessler, Wall Street Journal

Tempus fugit1

Virgil, 29 b.c.e.

In Las Vegas, 8-1 odds would be considered an excellent bet. Similarly, the eight benefits you saw in the previous chapter provided by a one- or two-Key Word Buffer is an excellent return on your invested energy. You can enhance one of the eight, thinking time, by adding more words to a Buffer that will buy you even more thinking time. The way to do this is to precede the Key Word(s) with a Paraphrase.

■ Paraphrase ■

The dictionary describes “para” as a prefix indicating adjacent, near, alongside, parallel, or beyond. The prefixes in “paralegal,” “paramedical,” “parapsychology,” and “paramilitary” refer to alternate but related forms of their root words: “legal,” “medical,” “psychology,” and “military.”

Paraphrasing is distinctly different from restating or rephrasing because the prefix “re-” indicates “again.” “Again” implies repetition, and repetition implies carrying forward the negative inference in a challenging question. A negative statement creates a negative perception.

To create a Paraphrase of the original question, begin with an interrogative word, such as:

What…

Why…

How…

…and continue on with the one or two Key Words and then conclude your Paraphrase with a period rather than a question mark:

What are my qualifications.

Why have we decided to release our product at this time.

How do we compete.

A period concludes a declarative statement, whereas a question mark implies uncertainty. You want to project only certainty to your audience—absolute certainty that you heard their question clearly and intend to answer it thoroughly.

To make a declarative statement, drop your voice at the end of your Paraphrase to create falling inflection. For that matter, use falling inflection at the end of every declarative sentence throughout your presentation to assert conviction. This technique is called Complete the Arc®, and you can learn about it in full detail in The Power Presenter.

Bear in mind that a Paraphrase is a new configuration of the original question and not a question about the original question. Asking a question about a question, as President Bush so painfully learned when he speculated, “Are you suggesting…?” is a tactic doomed to failure. Asking a question about a question implies that you weren’t listening and, worse, gives control back to the questioner.

A simple declarative sentence provides all of those eight positive benefits. However, there is one frequently used declarative sentence that can have a negative effect. Known as The Patronizing Paraphrase, this sentence is usually used in response to a particularly hostile question.

The Patronizing Paraphrase

Picture an IT product manager who has just finished a presentation about a product upgrade and then opens the floor to questions from an audience of existing customers.

The first question comes from a clearly irate CIO of a large financial institution:

We’ve spent millions of dollars on the first version of your solution, and it gave us nothing but problems—crashes, downtime, glitches, and endless repairs—and now you want us to upgrade to a new version? We’re still having problems with the earlier version! What are you going to do about that?

The product manager responds:

Quality is important to us…

Sound familiar? No doubt you’ve heard variations of the “Quality is important to us” trope countless times, among them:

On-time delivery is important to us…

Customer service is important to us…

Response time is important to us…

Cost-effective pricing is important to us…

Obviously, the irate CIO found serious deficiencies in the product quality—as did the customers who angrily cited issues with on-time delivery, customer service, response time, or pricing. So, when a presenter merely restates the issue and calls it important, the phrase is a blinding flash of the obvious—and therefore patronizing to the questioner. Of course, quality is important—the questioner just got finished saying that!

Unfortunately, the Patronizing Paraphrase has become a boilerplate mantra in Q&A sessions.

As the presenter, it is vitally important that you send the message that you hear and understand every questioner but do so without attempting to mirror your audience’s pain. This is especially true when, by the very challenging nature of the question, you or your company caused the pain in the first place. Instead, Buffer the key issue neutrally, with no emotional load, by saying:

What we’re doing to assure quality is…

Now you have two types of Buffers to buy you that all-important thinking time: the Key Word(s) of the previous chapter and even more time with the Paraphrase.

You can buy even more thinking time by adding even more words with a Buffer in front of a Buffer, known as a Double Buffer.

■ Double Buffers ■

If you search the web for “persuasive words,” you’ll find millions of results. Many of them refer to a Yale University study that ranked the 12 most persuasive words in the English language. “You” leads the list—ahead of “love” and even “money.” The study has never been substantiated by Yale but, like so many other internet urban myths, this one has taken on a life of its own.

More important, “you” is synonymous with a person’s name.

You can create a Double Buffer by inserting “you” before the Paraphrase and the Key Word. When you do, you send a clear message to your questioner that you were listening—just as Clinton did when he approached Marisa and repeated her words:

You know people who’ve lost their jobs and lost their homes.

Here is how you can add “you” or a form of “you” before a Paraphrase:

You want to know why we chose this price.

Your question is about how we compete.

You’re asking what my qualifications are.

You’d like to know why we decided to release our product at this time.

Just look at the length of the Double Buffer sentences above and compare them to the short Key Word Buffers below:

Our price is based on…

We compete by…

My qualifications are…

We’re releasing our product at this time because…

The additional length is another precious split second of thinking time.

Moreover, when you say “you,” you establish a direct connection with your questioner. You also create EyeConnect, the extended duration of engagement that you read about in Chapter Seven. While you are in EyeConnect with your questioner, you can watch for that person’s reaction to your Buffer. A frown indicates that you didn’t get it right, and a head nod indicates that you did. When you get a head nod from your questioner—and only after you get a head nod—are you free to move into your answer.

A head nod is the equivalent of the “Well, yeah, uh-huh” that Marisa gave Clinton when he told her that he’d heard her.

A head nod sends the message, “You heard me!” And as you read in the previous chapter, when the Buffer is accurate, the head nod is involuntary.

However, there are some other common Double Buffers that, like the Patronizing Paraphrase, can backfire. In the following section you’ll see—and very likely recognize—a collection of some frequently-used Double Buffers that you would do well to avoid.

Common Double Buffers to Avoid

One of the most common is:

The question is…

Presenters use this Double Buffer with the courteous intent of sharing the question with the rest of the audience. You can use “The question is…” once. You can use it twice. You can use it three times. But if you use it before every Paraphrase, you will sound as if you’re stalling for time.

Two other common stalls for time are:

That was a good question.

I’m glad you asked that.

These two Double Buffers are additional well-intentioned efforts at courtesy, this time by flattering the questioner. They have become boiler plate phrases repeatedly trotted out, not just in Q&A sessions but in panel meetings, fireside chats, and interviews in the media. Some of my clients have told me that they were taught to deploy those phrases to buy thinking time. Unfortunately, when they are deployed in response to a hostile question, they come across as a conspicuous stall for time, or worse, contentious sarcasm.

Imagine if, in response to the above example of the irate CIO’s hostile question about a product upgrade, the IT manager were to reply:

That was a good question.

Or:

I’m glad you asked that.

Clearly, it was not a good question, nor is the beleaguered IT manager really glad that the CIO, a valued customer, asked it.

On the other hand, if someone in the audience were to ask you a question that is good for you, such as:

All these new features in your product should allow us to save time and money, right?

You could then gleefully use both of those Double Buffers:

That was a good question! I’m glad you asked that!

From there you could go on to extol the virtues of your new product. But then if the next person were to ask you:

Yes, but why do you charge so much for your product?

You would hardly say:

That was a bad question! I’m not glad you asked that!

That would be judging or favoring one audience member over the other. Adjectives like “good” or “bad” in Double Buffers have the same deleterious effect as they do in single-word Buffers—they carry forward a negative balance.

Another common Double Buffer is:

What you’re really asking…

The implication of this phrase is that the questioner didn’t formulate the question correctly and that the presenter will benevolently reformulate it for them in much more articulate way.

And another often-used Double Buffer is:

If I understand your question…

The implication of “If I understand…” is the fatal message “I wasn’t listening.”

And one final common Double Buffer to avoid:

The issue/concern is…

If you use the word “concern” or “issue” when you retake the floor, you are confirming that there is a problem. Worse still, you would begin your answer by carrying forward a negative balance.

Delete all these troublesome Double Buffers from your vocabulary.

■ The Triple Fail-Safe ■

All the foregoing control measures, starting from the moment you retake the floor and continuing up to the moment when you are ready to provide an answer, can be summarized as the Triple Fail-Safe: three inflection points to keep you from moving into the wrong answer.

Fail-Safe One. If you cannot completely identify or understand the Roman Column in the question, do not answer. Instead, “Return to Sender.” Give the floor back to the questioner by taking responsibility and saying:

I’m sorry, I didn’t follow. Would you mind restating the question?

Fail-Safe Two. If you are certain that you have identified the Roman Column, retake the floor with a Buffer. As you deliver your Buffer, make EyeConnect with the questioner and watch for their reaction. If you see that person’s head nod, you can then move forward into your answer. If, despite your absolute certainty that you understood the Roman Column, you get a frown instead of a nod, do not move forward into the answer. Instead, Return to Sender by using one of these two options:

I’m sorry, I didn’t follow. Would you mind restating your question?

I heard every word you said, but I’m not following. Would you please restate your question for me?

Fail-Safe Three. Continue to Return to Sender for clarification until you can identify the Roman Column and get the head nods from the questioner. However, you can’t keep doing this indefinitely. At some point—after, say, two or three tries—having shown a sincere effort to understand, you can retake the floor and Buffer, beginning with:

What I hear you asking…

The Triple Fail-Safe gives you three checkpoints to avoid rushing headlong into the wrong answer. It also helps avoid the dreaded “You’re not listening!” perception or its variations “That’s not what I asked!” and “What I’m really asking….”

Even with the Triple Fail-Safe, there is always the possibility that, because the Roman Column bracketed a couple of related issues in a long rambling question, your answer might not fully address all of them. At that point, the worst that can happen is that the questioner will ask you a follow-on question such as, “Yes, but what I’d also like to know is…,” which is a lot milder than the dreaded “You’re not listening!”

■ Buffer Options Summary ■

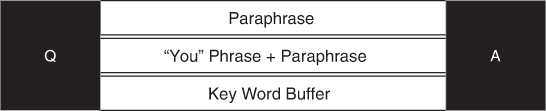

To summarize this chapter and the previous, you now have three Buffer options to bridge a question and an answer, as in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Buffer Summary

Option One: Only Key Word(s). State the Key Word(s) of the Roman Column and then roll directly into the answer. For instance, if you were to get an anodyne question about your how you plan to grow the head count in your company, your Key Word(s) Buffer would be:

The way we recruit talent is…

The Key Word(s) Buffer also immediately defuses the four frequently asked hostile questions:

Our prices are based on…

The way we compete is…

My qualifications include…

We chose this time because…

Option Two: Paraphrase + Key Word(s). Begin with a Paraphrase and then conclude with the Key Word(s), dropping your voice with falling inflection to create a vocal period:

How do we recruit talent.

Here is how the Paraphrase plus Key Word(s) Buffer works with the four hostile questions:

Why did we chose this price point.

How do we compete.

What are my qualifications.

Why have we decided to release our product at this time.

Option Three: “You” Phrase + Paraphrase + Key Word(s). Precede the Paraphrase with a “you” phrase and then follow it with the Key Word(s):

Your question is about how we recruit talent.

Here is how the “you” phrase preceding the Key Word(s) works with the four hostile questions:

You’d like to understand our pricing.

Your question is about how we compete.

You’re asking about my qualifications.

You’d like to know why we decided to release our product at this time.

By looking at all the options laid out on the page, you can readily see how the longer options buy you more thinking time.

However, if you use the second and third options too often, you will sound deliberate and stilted. Although the third option has the powerful “you” word along with its many benefits, too much of a good thing can become a bad thing. Too much milk or too many carrots can upset your stomach. Starting every Buffer with “you” makes you sound like a hoot owl.

The first option, only Key Word(s), provides almost no thinking time at all. You must have a firm grasp on the Roman Column before you take a single step forward. However, when you Buffer instantly with the Key Word(s) embedded in your answer, you will appear confident and in control.

The Key Word(s) Buffer is the most advanced form of Q&A, as you’ll see with three positive role models.

■ Key Word(s) Buffers in Action ■

![]()

(Video 27) BMW CEO Krueger on $4.1 Billion Bet on China https://youtu.be/FY1i5XxidyY?t=163

After BMW, the large German vehicle company, announced a large investment in a joint venture in China, the company’s CEO Harald Krueger sat for an interview with Bloomberg’s Tom Mackenzie who asked:

The price tag for the 25 percent was 3.6 billion euros, about 4.1 [billion] U.S. dollars—it’s about a quarter of your 2017 profits. Was it in line with expectations, or were you under pressure to pay a little bit over the odds to get that number-one stake?

Krueger picked up the four Key Words in Mackenzie’s question—“in line with expectations”—and repeated them at the beginning of his response:

It was in line with the expectations…

Having carried forward only the neutral noun “expectations,” Krueger did not have to deal with the “were you under pressure” implication when he continued on into his assured answer:

…I think it’s a good result for both sides definitely—and you need to see it as a strong long-term strategic investment having the majority.2

The Key Word Buffer is particularly effective in response to a challenging question because it demonstrates willingness to take responsibility for the challenge.

![]()

(Video 28) Zoom CEO Addresses ‘Zoombombing:’ We Had Some Missteps https://youtu.be/xk992LJ4N9M?t=69

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Zoom suddenly took its place alongside Kleenex, Xerox, and Google in our common vocabularies. The parent company, Zoom Video Communications, became a Wall Street and media darling, and any blips in the company’s performance were magnified. So, when internet trolls began intruding on Zoom sessions in what became known as “Zoombombing,” founder and CEO Eric Yuan came under fire. In an interview on CNN, their Chief Media Correspondent Brian Stelter asked Yuan:

Eric, what happened in the past few weeks? Is this just a situation where your—your service—your startup grew astronomically, a lot more quickly than you imagined it would?

Yuan was forthcoming and Buffered to the Key Word:

I think you’re right. Our service was a beautiful serv—business and allowed for anyone to be customers. However, during this COVID-19 crisis we moved too fast…

Yuan promptly followed his candor with a plan to rectify Zoombombing:

…over the past one week and two weeks we already took actions to fix those missteps.3

The final role model used Key Word Buffers for an entire Q&A session.

![]()

(Video 29) C-SPAN Foreign Press Briefing—April 15, 2003 https://www.c-span.org/video/?176198-1/foreign-press-briefing

Colin Powell was one of the best presenters and speakers ever to command a podium. As a general and as the U.S. Secretary of State, he faced the press on many occasions and maintained complete control each time. Shortly after the start of the Iraq War, Powell held a press conference at the Foreign Press Center in Washington, DC, during which he fielded 11 questions. Never once did he use a Paraphrase or a Double Buffer. In every case, he began his answer with the Key Word(s) in the reporters’ questions.

Consider Powell’s challenge: most of the journalists were not native English speakers, and so they phrased their questions with unusual syntax and accents. Moreover, as professional journalists, they all tried to cram in multiple questions when their turns came.

Let’s look at five of the eleven questions and how, in each instance, Powell promptly retook the floor with only the Key Word Buffer. Although his thorough answers continued well beyond his Key Word Buffer, in the interest of illustrating his model technique, you’ll see only the front ends of the five questions—the inflection points at which he retook the floor and exerted control by stating only the Key Word(s).

After a brief opening statement, Powell opened the floor. The first question came from Dmitry Kirsanov, of the Russian news agency TASS:

As the chief foreign policy adviser to the U.S. president, do you think the U.N. is still relevant and important from the point of view of prevention of military conflicts, not only humanitarian assistance? And do you think the organization needs to be reformed?4

What is the Roman Column? Certainly not “relevant” nor “reformed.” If Powell were to repeat either word, he would have validated the reporter’s assertion that the United Nations is irrelevant and in need of reform. This was the very opposite of the United States’ stated policy to support the U.N. and any answer would then be an uphill fight to justify the U.N., and would have landed him in the dark danger zone on the left of Figure 8.1, repeated here for your convenience as Figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2 Buffer Positioning

Instead, Powell’s first words upon retaking the floor were:

The U.N. remains an important organization…

The neutralizing Buffer allowed Powell to go on to offer supporting evidence:

The president and other leaders in the coalition—Prime Minister Blair, President Aznar, Prime Minister Berlusconi and many others, Prime Minister Howard of Australia—have all indicated that they believe the U.N. has a role to play as we go forward in the reconstruction and the rebuilding of Iraq.

His answer continued beyond this point, but let’s move on to another question, this one from Hoda Tawfik, of the newspaper, al-Ahram:

Sir, the Israelis said that they presented to you their modification on the roadmap. Have you received anything from the other side, from the Palestinians? And is it still open for change? You have told us before that it is not negotiable. And now on the settlements, on the settlements, as part of the roadmap, eh?…

Her question rambled so diffusely that a man seated directly behind Tawfik smiled. Powell heard the ramble and tried to get her to clarify:

The what?

She tried to explain:

On the settlements, which is part of the roadmap, we see the Israelis are—the activities of building settlements is really very high. We saw it on television. We saw reports…

Powell tried to get her to wrap it up by interjecting:

Thank you.

She continued:

…so what is your remarks on the settlements?

Did you identify the Roman Column? It was certainly not contained in Tawfik’s last words, “the settlements.” If Powell were to deal with that issue, he would again land in the dark danger zone on the left of Figure 10.2 because he would be validating her concern that the settlements were an obstacle to the U.S.-sponsored peace efforts. Any answer would then focus on only a subordinate aspect of the larger U.S. initiative: a peace plan called “the roadmap.” Moreover, Tawfik said that the settlements are part of the roadmap. So, Powell’s first words upon retaking the floor were:

With respect to the roadmap…

By using “the roadmap” as the Key Words rather than “the settlements,” Powell created a neutralizing Buffer. This allowed him to move on to a substantive rather than defensive statement:

…the roadmap will be released to the parties after Mr. Abu Mazen is confirmed, and it will be the roadmap draft that was finished last December.

He continued his answer, but let’s proceed to another question, this one from Khalid Adgrim from the Middle East News Agency of Egypt:

Mr. Secretary, a lot of fears have been made about who is next. And some people believed to be close with the administration said that the regimes backing Cairo and in Saudi Arabia should be nervous right now. How do you address that point? And does the U.S. [have] a plan to spread a set of values at gunpoint, in your view, at this point?

The words “a plan to spread a set of values at gunpoint…” accused the United States of acting as a villainous bully, and Powell could not give credence to that charge. When he retook the floor, he immediately countered the accusation: by applying the noted anti-drug slogan, “Just say, ‘No!’”

No, of course not.5

Adgrim’s question was a variation of the one we often see in courtroom dramas when an aggressive prosecutor asks a defendant, “When did you murder your partner?” This is known as a false assumption question, the assumption being that the defendant has already killed the partner. A non-felonious cocktail party version is “Have you stopped swiping your neighbor’s newspaper?”, the assumption being that you have been swiping the newspaper on a daily basis. And then there is the notorious version that Professor Ronald Hall of Stetson University cited in his book on logic:

One of the most famous is found in the classic question: “Have you stopped beating your wife?” Now clearly if we are required to answer “yes” or “no” to this question we are condemned out of our own mouths as being either a current wife-beater (if you answer “no”) or as a past one (if your answer is “yes”).6

Andy Kessler, the perceptive Wall Street Journal columnist, calls a false assumption a “Trap Question.” He agrees with Professor Hall, saying:

Just by answering, you’re assumed guilty.7

I agree with both the professor and Andy. Never answer a false assumption question. Refute it on the spot. Stop it in its tracks. Just say, “I don’t swipe my neighbor’s newspaper!”

Neither Colin Powell, nor you, nor any presenter is under any obligation to respond to an accusation that is untrue in any other way than with a complete refutation. If you are attacked with a question that contains or implies an inaccuracy, do as Colin Powell did: skip the Buffer and come back immediately with a rebuttal.

After he rebutted with “No, of course not,” Powell went on to support the U.S. position:

The president has spoken clearly about this, as recently as two days ago, over the weekend. We have concerns about Syria. We have let Syria know of our concerns. We also have concerns about some of the policies of Iran. We have made the Iranians fully aware of our concerns.

He concluded with a firm restatement of his rebuttal:

But there is no list.

Next, Powell recognized Jesus Izquivel from Proceso, a Mexican weekly magazine, who asked:

Mr. Secretary, I have a question on Cuba. Can you give us an assessment of what is your advice to the countries that are near to both in terms of the human rights situation in Cuba, especially to Mexico that has been too close to the Cuban government? And a quick second question. There [are] some countries that are calling the United States the “police of the world.” Do you agree with that?

“The police of the world…” This was another question that accused the United States of acting as a villainous bully—another false assumption question. Here again, Powell could not give any credence to this charge in his reply. However, because it was a double question, he fielded them in order, Buffering to the Cuba question first:

First of all, with respect to Cuba, it has always had a horrible human rights record, and rather than improving as we go into the twenty-first century, it’s getting worse.

Notice that Powell began his response with “First of all…,” committing himself to answer the second question (about the police of the world)—which he did as you will see in a moment. While I cautioned you to avoid using enumeration with multiple questions, Colin Powell, as a role model of advanced Q&A techniques, can and does. If you are not Colin Powell, handle one question at a time.

After providing an answer about Cuba, Powell moved on to the second part of Izquivel’s question about the police of the world:

With respect to the United States being the policemen of the world, we do not seek war, we do not look for wars, we do not need wars, we do not want wars.

Just say “No!” to false assumptions.

Powell remained in complete control with every other question in the press conference, listening attentively, Buffering with only the Key Word(s), answering thoroughly, and handling multiple questions with equanimity.

Then Powell called on the man who had smiled at Hoda Tawfik’s rambling multiple question, and he asked:

Mr. Secretary, there seems to be some hopeful sounds coming out of your administration and North Korea on a settlement there. Do you think that there’s likely to be a meeting soon between the administration and North Korea? In what sort of forum?

Breaking into a big grin, Powell said:

Pretty good. You’re trying to get it all at once, aren’t you?8

■ The Making of a Master ■

How did Colin Powell develop his expertise? In his book It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership, he wrote, “my education came on the job.”9 I also had the rare privilege of meeting him in person and asking my question directly. His answer:

I first learned about presenting and answering questions in 1967, at Officer Training school in Fort Benning, Georgia, in an Instructor Training Course. They taught me to be sure to stand up straight, engage directly with the audience, and avoid affectation.

One of the most important lessons I learned about answering questions is to get to the point quickly. Leave them with a sound bite.

I also learned that there is no such thing as a stupid question, only stupid answers. The rest of the audience may be snickering at what they think is a stupid question, but the presenter must never react that way or talk down to a questioner.

Much of my learning about how to handle questions came from watching people who are really good at it. People like Ronald Reagan and Cap Weinberger*. I observed Reagan’s and Weinberger’s best practices and internalized them. My key takeaways were: show confidence, never let them see you sweat, and always understand who your audience is.

Whenever I face the press, I know that I’m speaking not just to them but to the American people. My relationship with the press is not adversarial. We have the same job: to inform the public. So, I report what we’ve done—without giving away state secrets—and deliver what they want to know.

That same principle applies in business. It’s always important to know your audience. Whenever I speak to a corporate organization, I research their track record, their stock performance, their industry, and I bring up that information in my presentation. I think about what my audience knows and what they want to know. I design my message and my answers to provide what they want.

Fielding questions in business is no different than fielding questions in the military and diplomatic sectors. I anticipate the questions that the audience is likely to ask and what my response will be. I have a random-access memory, and when I hear a question coming, I recognize it and deliver my prepared message in my response.

When I retake the floor, I often precede my answer with the words “With respect to….” This simple technique has two benefits: it gives me a moment to think, and it shows respect to the audience. And that is the basis of all communication: care about your audience and show them respect.10

Now that you’ve learned what to do when you retake the floor, you’re ready to move on to the next step in the Suasive Cycle: Answering the Question.

Most people want to start learning how to handle tough questions by learning how to provide the best answer, yet I’m only getting around to answering here, just past the midpoint of the book—intentionally. The rationale for this delay to stress the importance of mastering Active Listening and Buffering before you answer. Without those skills, you risk giving the wrong answer and hearing the dreaded reaction of the audience’s charge:

That’s not what I asked!

If you do not Listen and Buffer effectively, do not pass “Go” and do not collect $200.11

* Powell served as a national security adviser in the Reagan administration and as a senior military aide to Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger