Chapter 4

Developing your cultural intelligence

Would you ever go to someone else’s house and say, ‘We put our feet on the table at my house, so I’m going to do the same at your house’? You would never. You would sit back, observe how your hosts conduct themselves and adjust your behaviour. Out of courtesy to your hosts, and out of respect for their rules and guidelines, you’ll try to adapt to your new environment (within reason, of course). The same principle applies when you’re a new employee at an organisation. Your company is someone else’s house and you have just arrived. So why don’t we bring this attitude to our places of work?

Cultural intelligence (or cultural quotient, CQ) is a person’s ability to interpret, understand, become comfortable with and operate within a culture that is different from their own. Just as building your EQ starts with understanding and managing your own emotions, building your CQ starts with examining your beliefs about your own cultural upbringing, and then adjusting them to your environment. Our cultural values are a product of our education and socialisation. Understanding your own culture will also help you understand why there might be tension between your own and another person’s or organisation’s culture. A number of years ago, I discussed the idea of CQ with one of my mentors. We talked about the difficulty of performing well in a culture that differs from one’s own, and he gave me the following advice: ‘Adaptability is key. Be flexible in style, learn the culture and calibrate.’ He encouraged me to ‘remove the judgement of “my culture” versus “their culture”’ and to ‘allow different parts of [my] personality to play out in different situations’. ‘Our personalities are broad enough,’ he advised, telling me to ‘differentiate between [my own] values or core identity and style.’

| As a woman, especially in my particular industry where most of our customers are Indian Muslim [men], it is not acceptable for me to be talking to them. So you learn to understand where they come from. Many times I have extended my hand and then I take it back because they don’t shake hands with women. So you learn to understand your industry and adapt to it.” – Connie Mashaba, Manager, Amka Products and Former CEO of Black Like Me |

Considering the global nature of the economy and how connected we are, you will likely work within different organisational cultures with people of different cultures and possibly even from different countries. Building your CQ is therefore an important skill. Understanding and assessing your own culture against another is like a muscle that you have to exercise consistently to build and maintain relationships with different people.

As I’ve shown in the previous chapter, effective relationships are key to making an impact at work and serving your clients or customers well. Consider the following: if the cross-cultural team of a company cannot get along, or does not communicate effectively with each other, how can they deliver the best solution, service or product? They can’t. If different racial, religious and gender groups are not represented within an organisation’s marketing team, or if team members who come from different cultures don’t have enough power or agency to speak up, it can have disastrous effects. Just think of Gucci’s (now discontinued) Blackface sweater, H&M’s ‘coolest monkey in the jungle’ T-shirt or Pepsi’s ill-fated commercial with Kendall Jenner.

When I moved to South Africa nine years ago, I had to adapt. As an American, for example, I was accustomed to walking up to customer service employees in stores and launching straight into my question. In South Africa, however, people expect you to recognise them as a person before you get to whatever role they have or service that they provide. Today, when I walk up to a person in a store, I greet them first. I wait for the person to respond, and only then do I proceed to ask my question. Old habits die hard and sometimes I forget, but I try my best to remember. This way of interacting has become such a part of who I am that I get upset when people don’t greet me before asking me a question. It just serves to demonstrate that culture is fluid and it can and does evolve. I’m glad I inquired about the significance of greeting and I’m grateful someone took the time to explain it to me. When I think about it, recognising another’s humanity before their role at work is a beautiful concept, and it helps me to remember the humanity in every person I interact with.

| What should you listen to or look for to figure out how an organisation works? You need to observe and understand how people both interact and present themselves.” – Nomfanelo Magwentshu |

All of us look at the world through the lens of culture, but if we don’t work hard to understand this, we will be unable to see past or around it. We have all grown up in a particular culture, and some of us have even grown up in multiple cultures: we might have had a certain culture at home, a different one in our greater community, another one at school and still another in our religious community. We judge people based on what we think is appropriate behaviour, hygiene, dress, speech, etc, and we choose, befriend, dismiss and/or categorise people based on those filters. But it’s important to understand that no culture is better than another; they’re just different. Remember that if we judge others’ cultures to be less than our own, we’re no better than those who deem their culture to be superior to ours.

Criticising other cultures also creates distance between us and those who consider themselves part of that culture. Think back to a moment in your life when you have felt judged by someone. How did it feel? Probably not so great. It definitely did not build a positive connection between you and that person. The negative energy you felt from the person who judged you is the same type of energy we exude when we judge others. In other words: if we can learn to approach different cultures with curiosity, openness and the desire and effort to understand, we will be able to grow our CQ. Do you use culture as another way to separate yourself from or to judge others? Learning about other cultures provides you with the opportunity to expand your world view and the world view of others.

My aim in this chapter is not to give you all the answers – I certainly don’t have them! – but rather to highlight several different parameters of culture and how those cultural elements show up in various organisations. Hopefully, these examples will help you to identify the points of alignment and difference between you and your surroundings. Differences can be a source of tension, so it’s helpful to assess them upfront so that you can proactively address them.

| In corporate Nigeria, if your meeting is scheduled for 10 am, you’re probably going to see the CEO arrive at the meeting at 1 pm if you’re lucky. That’s because Nigerians’ culture has permeated into their corporate space. But in South African corporate spaces, you have to work in line with the culture of the corporate space you’re in. You have to fit in and manage your own cultural biases so that they don’t make you ineffective at work.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Assess your culture

Before you assess your organisation’s culture, it’s imperative that you assess your own. If you understand how beholden you are to your culture, you’ll be able to see how wide the gap is between your own cultural beliefs and those of the organisation and/or the people that work there. Assess whether your cultural beliefs are helping you to be successful in the company. The three key areas that are useful to examine are your culture, the culture of others and the culture of your organisation.

Geert Hofstede, the late Dutch social psychologist, identified six dimensions (or characteristics) with which you can assess your culture and how strongly you subscribe to its norms. Each dimension is expressed on a scale running from 0 to 100. Think about where your culture falls on the scale of each of the following dimensions:

1. Individualism: The extent to which people within a culture are seen as individuals or as part of a bigger community. People within a culture that prioritises the bigger community prefer to do what is in the best interest of the group as a whole, as opposed to what benefits individuals.

2. Power distance: The extent to which power is distributed in a culture and the hierarchical distance between those who make the decisions and those who are affected by those decisions. Countries that have a high power distance are comfortable with the hierarchy and do not aspire to equalise the distribution of power.

3. Masculinity: In ‘masculine’ cultures, there is a focus on winning, assertiveness, material success and the ideas ‘bigger is better’ and ‘the more the better’. In ‘feminine’ cultures, there is less of a difference between the genders.

4. Uncertainty avoidance: This points to the level of comfort a culture has with uncertainty, ambiguity and the unknown. The less comfortable a culture is with uncertainty, the more likely it is to have fixed habits, rules and rituals.

5. Long-term orientation: The extent to which a culture is focused on the future. Cultures with a long-term orientation are willing to delay short-term gratification (eg material, social, emotional) in order to prepare for the future. People with this cultural perspective value persistence, adaptability, perseverance and saving.

6. Indulgence: The extent to which a society allows for the relatively free gratification of basic and instinctual human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Cultures with more restraint repress the gratification of needs and manage them by implementing severe social norms.

Where on the scale does your culture fall on each of these six dimensions? In what ways does this impact how you see the world and interact with people who are different from you?

| Sometimes we are unprofessional in the way we understand jobs and etiquette. I think it’s to be expected, because we don’t come from multiple generations of working people. We haven’t learnt those mannerisms and, frankly, some aspects of our culture don’t serve us well in the classic corporate space.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Based on my experience, I think there are certain elements of Black culture and how we were raised that can get in the way of our being successful at work. I’ve provided a few examples below, so see which ones apply to you.

Perspective on time: Many of us grew up in cultures where nothing ever starts on time (think of, for example, weddings, funerals and family events). I feel this has lessened our respect for time. In America, we call it ‘Coloured People Time’, and in Africa, ‘Africa Time’. Maybe there are no consequences in your family and/or social circles if you run late. However, in the working world, time equals money and credibility, so timing has consequences. At work, if you can’t do something as simple as deliver a task on time, show up on time for work or be punctual for appointments, how can your employer trust you with bigger challenges and responsibilities? Not sticking to deadlines, for instance, means that your manager might have to stay up late to review your work before it can be finalised. There are repercussions for being late in whatever you do, and you are being judged if you don’t honour those time commitments. For instance, I used to tell consultants that showing up on time for a meeting doesn’t start the morning of the meeting: it starts the night before. You have to go to bed on time so that you can wake up on time so that you can leave the house on time (even factoring in traffic) so that you are ready when the meeting starts. Don’t make habitual lateness a part of your brand. If you are in an organisational culture that is highly time-conscious, make sure you put the right measures in place to honour that.

| There is a script in corporate America which wasn’t designed for us. They didn’t have us nor our culture in mind. The culture of the corporate environment is a different language with a different cadence. All too often, young professionals of colour don’t understand that. ‘Show up and be on time.’ We had to let go of one of our African-American female employees, one of the top ones, a PhD student, because she kept showing up to work 30 minutes late. She was showing up to meetings late. Everything was late. Could she not set her alarm clock?” – Tina Taylor |

Questioning authority and speaking up: Despite being separated by oceans, languages and cultures, there are some qualities that appear to be common across the diaspora. One of these is that many of us grew up in households where we were seen and not heard. We were not encouraged to challenge or correct our parents or anyone older than us. Our opinions were not valued or solicited. This way of operating may have worked well for our parents in fostering order and discipline at home, but it does not necessarily serve us well in the workplace. Companies hire young people because they want to hear their perspectives, opinions and ideas, and because they might be more aware of trends and what younger consumers want. They hire young professionals to be not just doers but also thinkers. Because of that, you have an obligation to offer your thoughts.

Sometimes we have to disagree, challenge or even interrupt our seniors. Remember that if you don’t speak up, you deny your colleagues the privilege of hearing your unique point of view. Over the years, I’ve seen many people struggling in corporate cultures because disagreeing with, interrupting or challenging seniors goes against their upbringing. Time and time again, I received feedback from managers that a person of colour was struggling to speak up. This was especially apparent during problem-solving sessions at McKinsey. To sketch the scene: during these sessions, a team with members from all levels sits around a table and discusses client issues. These discussions can get quite lively because that is what happens when you put a bunch of highly intelligent, opinionated people in a room to discuss a topic about which they are passionate. In order to get into the conversation, you might have to interrupt someone who is more senior to you. It’s a high-pressure, highstakes scenario because no one wants to look stupid or clueless in that setting. In my experience, very rarely did I hear feedback that a white person had trouble speaking up in these sessions. This made me think that our socialisation as Black people does not adequately prepare us for these types of high-performance, highpressure environments.

Let me give you an example. A few years ago, a white colleague of mine told me that his family had hosted a foreign exchange student when he was a kid. Before his parents made the decision to host the student, they called all the kids together for a family meeting. The meeting was to vote whether or not the foreign exchange student should come and live with them. Each person, including the kids, had a vote and if the outcome was not unanimous, the student could not come. When I heard this story I was fascinated that the parents even called a vote at all and that each family member’s vote had equal weight. I can’t think of too many Black parents who would call a family vote! And, even if they did, they would not give an equal vote to each person – especially not to the children.

The idea that children are not to get into grown folks’ business is not a bad thing in and of itself. However, it made me wonder: how different would I and other Black people have been had we grown up in homes with a bit more of a democratic culture? Would I have been more outspoken? Would I have found my voice earlier? Would I have been more comfortable challenging authority earlier in my career? While order and discipline are great parenting goals for the first 18 years of children’s lives, I’m not sure that that philosophy serves them for the years between 19 and 70. You will spend more time outside your parents’ house than inside it. I’m not suggesting that you have to choose between order and discipline on the one hand, and chaos and anarchy on the other. I believe there is a happy medium and I challenge you to find it when you’re raising your own kids. They will be the next generation of employees and entrepreneurs.

| Some of the feedback that I received over the years I took with a pinch of salt. It took maturity. Some of the things, I could tell, came down to cultural differences and others came down to me. I had to be brave and smart. I often understood the feedback, but I was not going to change me, because that’s what makes me unique.” – Dr Puleng Makhoalibe |

Asking for help: In some environments, asking for help is seen as a sign of weakness, and being seen as weak is the last thing you want, which is understandable. It feels as though asking for help makes you appear dependent on others, that you are not selfsufficient, that you don’t know everything, and it makes you vulnerable. For those of us who have grown up in countries with a long history of racial discrimination, I think we oftentimes feel that we have something to prove. You might feel the same way if you are a woman in a male-dominated industry or if you’re the youngest person in your department. We don’t want to be perceived as people who don’t have what it takes or that we’re not as smart as everyone else. Sometimes we have to ask ourselves what is more important: a) my desire to prove that I can do this on my own, or b) my desire to make sure that this piece of work is done to the highest quality and in the most efficient way? Asking for help is critical to being successful at work, especially early in your career, because you are still learning the ropes.

Mistrust of, or lack of exposure to, those that are different from us: Many of us grew up in very homogeneous environments where we were not exposed to people who look and sound different from us. Some of us grew up in environments where we were a minority, and the exposure we might have had with the majority group was not very positive; sometimes, people in our families and communities even spoke ill of people who were different from us, based on their negative experiences. These messages and experiences have shaped our perceptions and they have created in us an inability or unwillingness to establish relationships with people who do not look like us. Regardless of your environment, you are going to have to learn to build relationships with, and garner the support of, people of different cultures, genders, age groups, races or socioeconomic status. Examine what stereotypes you might be holding against certain groups. Trying to find what you have in common (for example, professional interests, hobbies) can help bridge the gap between you and the other person.

A former colleague of mine once told me that he wanted to work on his communication skills. I suggested someone in our office who is a great communicator, but he said he was not sure how to build a relationship with a woman. I probed to understand what his issue was. Was he worried about how it would look to others? Was it the fact that she was senior to him? He said no; he had no issue with forming relationships with senior men in the office. Then something made me ask, ‘How was your relationship with your mother?’ ‘I didn’t have one,’ he told me. ‘My mother died when I was very young and I was raised solely by my father and was mostly surrounded by men while growing up.’ ‘Well, maybe that’s the issue,’ I said. He suddenly had an ‘aha’ moment: he realised that his past experiences affected his ability to form relationships in the present.

Gender roles: Many of us grew up in cultures where men and women, even girls and boys, played very specific roles in our homes, houses of worship and communities. Unfortunately, we take some of those beliefs to our jobs. We believe that certain genders should behave in certain ways or take on certain roles. We also believe that it is inappropriate for us to take on the responsibilities of other genders. We might also find it difficult to report to, or build relationships with, people who do not fit into our preconceived notions of gender roles. For these reasons, it is important for us to examine the ways in which our upbringing can get in the way of achieving our goals at work. I was raised in Alabama, which is in the southern part of the USA. During my childhood, girls were raised to be demure, subservient and docile. Good southern ladies didn’t make a fuss. Unfortunately for me, I took that attitude into my career: I didn’t push back on opportunities that didn’t help to grow me or that weren’t putting my gifts and talents to use.

| We train our boys to be brave, but we don’t do the same for the girls. At work, men would put their hands up all the time when new opportunities would come along. So we would have to go and tell the women that they should apply, too. And they would say,‘No, I don’t think so. I don’t have [the qualifications and/or experience].’ It still is very difficult for women to put their hands up.” – Penny Moumakwa |

Individualistic vs collectivistic: Individualistic cultures are all about the individual, while collectivistic communities are about the group as a whole. In an organisation, you have to strike the right balance between these two poles. Your focus can’t just be on yourself, but neither should it just be on the organisation. Sometimes you have to make decisions that are right for your career. This means that you might have to turn down an opportunity that doesn’t make sense for your career, even though your decision might upset someone in your organisation. At other times you might have to take on certain assignments that you are not excited about but that your organisation needs you to handle.

A big part of working in the corporate world is being able to talk about yourself, what you’re working on, what you’re good at and what you have achieved. A corporate is much like heaven: there are no group or family’n friend entry programmes, as everyone is judged on his or her individual merit and contribution, so it’s best to be clear on what yours are. I grew up in the US. I’ve lived in South Africa for almost ten years. I’ve worked and socialised with Kenyans, Ghanaians, Nigerians, Cameroonians and South Africans. This is a shared experience: in general (although there are always notable exceptions), we as Black people struggle to speak about ourselves and our individual accomplishments.

Admitting mistakes and taking risks: In my experience, we as Black people have a lot of pressure on us to succeed. In environments with a history of racial segregation, many of us are told that we can’t fail because it will reflect poorly on the next Black person, and that another Black person will never get another chance because we failed. This was exactly the collective sentiment when President Barack Obama was inaugurated in 2009. Many Black people felt like he couldn’t mess this up, because if he did, we would never see another Black president in our lifetime. I believe we take this attitude into our work environments. We feel there is no room for error, so we try to cover up mistakes, we fail to take risks or we are indecisive because we don’t want to make wrong choices. The problem with this attitude is that we miss out on the lessons to be learnt from taking risks and making mistakes.

Other aspects specific to your family, country or culture: I once coached a woman from an African country; she had a lot of potential and expressed her aspirations to advance in her organisation. I asked her what was holding her back from going after what she wanted, and she said that, in her culture, they ‘wait for things to come to [them]. We don’t go after things,’ she told me. Let me tell you this for free: if you want something in an organisation, others are not going to figure out how you should go about getting it. You have to figure out what you want and how to get it, and then put a plan in action to achieve it. Assess the difference between your culture and that of the organisation. The bigger the gap, the harder you will have to work to adjust your attitude and behaviour in an authentic way.

| Young Black professionals get tripped up when they don’t know how to navigate the spaces they’re in. It then starts manifesting itself in other ways and starts looking like laziness or unprofessionalism.” – Kagiso Molotsi |

The issues that have played a big role – and sometimes tripped me up – in my career have been my thoughts on gender roles, my focus on the collective versus the individual, and my discomfort with pushing back on authority. My cultural background led me to take on roles that were not in the best interest of either my career or my own personal development. It is important that we learn how to strike the right balance; it took me a long time to get it right.

Regardless of where you work, you cannot make assumptions about what type of culture the organisation adheres to. We assume that a company will or should have a culture similar to the dominant culture of the country in which it is located. This is definitely not the case. For example, if you work for a multinational that is operating in South Africa, the culture of your organisation could be Western, male-dominated and individualistic because that is the dominant culture of the country the company was founded in. Any South African who wants to be successful in that particular environment will need to adapt to that style of performing, delivering and communicating, which, interestingly, is the antithesis of how most South Africans grew up. It will be up to you to assess your company’s culture and decide whether it’s for you or not. You will have to do the hard work of deciding what aspects of your upbringing you’re willing to relax in order to be successful in that culture.

Understanding your organisation’s culture

Up to this point, I’ve been discussing personal culture, but now I’d like us to shift our attention to organisational culture. Organisational culture is the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, norms, language, behaviours and practices that characterises an institution or organisation. Cameron Sepah, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, argues that, regardless of the values listed on the company website, an organisation’s culture is defined by who it recruits, rewards, promotes and fires. Some people believe that that tells you everything you need to know about what a company values. I’d like to highlight three frameworks for evaluating culture, each of which presents different elements that you should explore at your organisation.

Organisational Culture Profile: Within this framework, researchers Jennifer Chatman, David F Caldwell and Charles A O’Reilly III identified seven dimensions of culture: innovation (how much risktaking and innovation are encouraged), stability (how much growth and change are encouraged), people orientation (the extent to which employees and the impact on them are considered in decision-making), outcome orientation (the amount of focus on results versus process), easy-going (the level of competition versus collaboration), detail orientation (the amount of focus on exactness) and team orientation (how much work is structured around individuals or team achievement).

Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument: University of Michigan professors Robert E Quinn and Kim S Cameron developed a framework which looks at six aspects of culture: dominant characteristics, organisational leadership, management of employees, organisation glue, strategic emphases and the criteria of success. The output from this model is called the Competing Values Framework, which, in turn, identifies four areas around which cultures are developed: how internally focused or externally focused the organisation is and how much flexibility/discretion or stability/control exists in the organisation. Based on these four areas, Quinn and Cameron’s research shows that there are four types of cultures: Clan Culture, which is entrenched in teamwork; Adhocracy Culture, which is grounded in enthusiasm and innovation; Market Culture, which is rooted in a competitive environment where the focus is on driving for results; and Hierarchy Culture, which is grounded in order and command.

Integrated Culture Framework: This model was designed by Jeremiah Lee, Jesse Price, J Yo-Jud Cheng and my Harvard Business School professor Boris Groysberg. The authors argue that organisational cultures operate according to two sets of dimensions: how an organisation manages change, and how closely people in an organisation work together. The model posits eight types of culture: learning, purpose, caring, order, safety, authority, results and enjoyment. The names of each of these cultures speak to their specific focus.

Each of the abovementioned cultures has a unique style of leadership, value drivers and strategic focus. There is no perfect culture. Some people are better suited to certain kinds of cultures based on their personalities, values and motivations. Each type of culture has its advantages and disadvantages. Certain cultures work better for specific organisations because of the organisation’s strategic priorities, the customers they serve and the industries in which they operate. Your organisation’s culture may not fit neatly into one of these categories, however: there may be a dominant culture but there can also be different subcultures that exist in various parts of the organisation. While these models focus on different areas, I believe each one highlights an element of culture that you should investigate within your company.

Before you accepted the offer for your position, hopefully you did some due diligence to determine whether or not the organisation’s culture was a good fit for you. Nevertheless, there will still be many details about your new employer that you can only learn by being on the inside. In many ways, the recruiting process is like a first date, because everyone is putting their best foot forward. However, you might only see the good, the bad and ugly once you’re inside the organisation. Remember that no company is perfect, because every company has imperfect people working for them. Every organisation has its fair share of problems, even though they may vary in severity from company to company.

A big part of your role as a new hire is to understand the culture more deeply and understand how you can fit into it in an authentic way. You were drawn to your chosen company’s brand for a number of reasons. In addition, the company has been operating successfully enough to be in a position to hire people for many years – if not decades – and there is a reason why. Now is the time to peel back the layers and learn what makes this organisation tick.

There are the values that every company lists on its website . . . and then there are the ways in which they play out in reality. To use an analogy: when you’ve just met someone, you would not like that person to tell you everything that they think is wrong with you. In general, it is better to approach people with their strengths in mind. Companies are the same. Focus on the positive, what is working, why this company or brand has been able to stand the test of time and weather various economic and global storms. There is something that you liked about the company and it made you want to join. Focus on those elements and dive deeply into them so that you can appreciate how the company operates.

| I had to almost unlearn what I knew initially and then later on bring what I knew to the table once I had learnt the basics. That humbled me a bit. When you walk into a new situation, it doesn’t matter how much you know or how much experience you have, you need to understand that environment.”– Nomfanelo Magwentshu |

Over the course of my career I’ve worked full-time for six different organisations, and each one had its own distinctive culture. Aon Hewitt, my first employer after university, had a very relaxed, youthful culture. Arthur Andersen, the company I joined next, was very hierarchical, and there was a distinct line drawn between support staff and consultants (those who generated revenue for the organisation). They had strict (and sometimes unspoken) guidelines, ranging from dress code (no sleeveless tops for ladies and no facial hair for men if they wanted to be made partner) to the specific colours to use in client PowerPoint presentations. Deloitte, the next company, was very diverse, collegial and friendly.

Then I joined the Fulton County Schools Board (Atlanta, Georgia), which was hierarchical, with a cultural distinction even in its three-floor central office building. The employees on the top floor wore suits every day, because that was where the Superintendent (akin to the CEO) had his office. The employees on the ground floor dressed much more casually. At McKinsey, too, I quickly learnt that the company had a very specific way of solving problems, of writing, speaking and designing business communications (for instance, in email or PowerPoint presentations). I quickly learnt that if I wanted to be heard, seen as effective or thought well of, I had best learn, practise and perfect what they called ‘the McKinsey Way’. After my years there, I worked briefly for a startup where the atmosphere was much more relaxed, and where everybody pitched in to accomplish whatever needed to be done. Know that different environments have different pressures, expectations and personalities, which may trigger emotions or reveal qualities within you that you did not know were there. This is why the process of knowing and understanding yourself is an ongoing one.

Be a student of your organisation

Below, I share a few examples of how the different elements of culture have played out in the organisations that I’ve worked with and for as an employee and a consultant. Using this information, see if you can evaluate your company’s organisational culture and design.

Listen out for commonly used words: The words that I heard spoken at Fulton County Schools were very different from the ones I heard at Deloitte. The words that are used in an organisation speak specifically to what it does and what it holds to be true. What are the most commonly used words in your organisation? Why do you think those words are used so frequently? How do those words align with what the business does and values?

Uncover the unwritten rules for success: The expectation on the part of some consulting firms that their consultants will take part in extracurricular activities to build office morale is not written down anywhere. If you look at a consultant’s job description, this additional expectation does not feature in it. Nevertheless, consultants are judged on their participation. At a former client of mine, a new hire has to be properly introduced by a more tenured person with credibility in order to be taken seriously. Without this proper introduction and contextualisation of the new hire’s roles, people would not accept meeting invites nor respond to emails from this person. What is expected of you outside your standard job description? What might people be evaluating you on that you’re not aware of? When you first join the organisation, how do you need to communicate, show up and deliver in order to build trust in you and your abilities? Historically, what has derailed people who weren’t successful in the organisation?

Understand how and why people communicate: McKinsey was the first company I worked for that communicated in a very specific way. They call it ‘top-down’ communication. It basically means that when you’re communicating, you should start with the ‘so what’ – the most important recommendation or takeaway – of your message and then call attention to the supporting details behind it. This is in stark contrast to ‘bottom-up’ communication in which you start with the details and work your way up to the ‘so what’. I once asked a partner why top-down communication was the preferred style at McKinsey: ‘We’re usually working with C-suite leaders who don’t have much time or headspace,’ he said. ‘So when you get the opportunity to communicate with them, you need to grab their attention with the main idea so that they’ll listen to the rest of what you have to say.’

Once I heard that, I understood the reason behind their staunch devotion to top-down communication. What I also understood was that McKinsey partners are the same as C-suite leaders: they, too, don’t have much time, so if I wanted to grab their attention, I had to communicate with them in a top-down fashion as well. All senior employees at McKinsey, I realised, were trained to be top-down communicators, so if that is how they were trained, it was highly unlikely that they would want to receive communication in a different way. What is the most commonly used communication style in your organisation? Why is it preferred? How different is the organisation’s communication style from your natural communication style?

Notice the physical layout of your office: When I worked at Deloitte, one of my clients was a global confectionery and pet food company. When I arrived at their headquarters, I was surprised to see that the CFO was sitting in a cubicle in an open-plan office. He didn’t have a fancy office or an assistant who acted as a gatekeeper to restrict access to him. He was as accessible as the most junior person on the team. That office set-up told me a lot about their culture. It let me know that this was not an organisation for prima donnas or divas. This was a down-to-earth, no-frills type of culture where everyone was valued and the focus was solely on getting the work done.

From my time at McKinsey, I remember how the company prided itself on being a trusted client advisor. A big part of building and maintaining that trust is making sure that client information stays confidential. For instance, non-McKinsey guests were not allowed into the client-confidential areas of the office. On the rare occasions that they were allowed in (always due to space constraints), a McKinsey employee was supposed to walk the path that the guest would walk to ensure that there was no confidential information visible on whiteboards or flip charts. The McKinsey employee was supposed to stay with the guest the entire time to make sure they didn’t wander off and accidentally see something they weren’t supposed to. If confidentiality is a big freakin’ deal for the company, it needs to be important to its employees too. How is your organisation’s space configured? Why do you think it’s configured in that way? What message does the physical layout convey?

| A new joiner should ask questions to understand how their position fits into the organisation and business strategy. They should be curious about the values and behaviours that drive the organisational culture of reward and recognition. They should ask if collaboration is encouraged? How are decisions made? How empowered are they? What exactly does the organisation value and what does it look like in terms of the behaviours expected? A new joiner should do their homework to hone their craft and become fully equipped to operate in the culture. I encourage new joiners to seek out a mentor, informal or formal. They should ask about the unwritten norms. What are the things that can derail a career?” – Shenece Garner Johns, Director, Talent and Organisational Capability, Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control |

Even if they say they are, many people in many organisations are not sincerely open to doing things differently and changing certain elements of their company culture. Looking back at all the people I’ve worked with, I understand how beholden employees can be to their company culture. Why wouldn’t they be? If their company is extremely successful, why should they fix it if it ain’t broke? You, too, might encounter a great deal of bias and resistance to change in certain corporate environments. For example, if you have to sacrifice your energy, time with family and friends, maybe even your health and your relationships, in order to succeed in a certain company, you would probably believe your company is the greatest place to work. If not, what would all the sacrifices be for? You’d never make these kinds of sacrifices for a mediocre environment! So it stands to reason that when employees feel they’re working for the greatest company ever, why would they ever be motivated to change?

If I had it to do all over again, I would spend a lot more time understanding the cultures of the organisations I’ve worked for and with. This would have enabled me to tailor my messages and ideas in ways that were more palatable for employees and leaders. Delivering messages in a way that was customised to those environments would have made me even more effective. In hindsight, I realise that walking into a new space and telling people what they need to do differently is like walking into a restaurant for the first time and telling the kitchen staff how to prepare the food faster. Regardless of how great your ideas are, you have to deliver them at the right time and package them in a way that makes it easy for people to digest.

If you want to be an effective communicator, understanding the context is crucial. I liken it to feeding children at different stages. You have to mash up a baby’s food because they have no teeth. For a toddler, you have to cut their food for them. For an older child, you can serve it as is. While you’re serving the same food, you’re presenting it differently, based on what they can manage. The same holds for communication: you have to meet people where they are socially and psychologically, and in order to do that successfully, you have to listen and learn. Spend time inquiring, listening and observing so that your ideas are well received and ultimately considered as part of the solution.

The business you’re in

| Try to learn as much as possible. Many people that work in a company never pick up the annual report of that company. I interned at Enterprise Rent-a-Car . . . it’s actually quite amazing, even though I never understood this: Enterprise doesn’t make money from renting cars. That’s what you would think. Enterprise actually makes money from selling insurance. Read and learn about your company and what they do. At 18 years old I did my job, but I wasn’t very good at it because I didn’t put in the time and I didn’t really understand how the organisation was structured, so I didn’t last very long.” – Ronald Tamale |

For the last few years, I’ve been facilitating a course for new hires at Bain & Company South Africa, called ‘Building Credibility’. As part of the course I ask the newly minted consultants the following question: ‘What business is Bain in?’ Their answers are always consulting, management consulting and problem-solving. While these are all true, ultimately Bain is in the business of making an impact. A client wants to know that their business is better off for having engaged the services of Bain. One way of describing impact is to say that it is the difference between before your organisation’s product, service, input, advice and/or actions arrived on the scene and after your organisation’s product, service, input, advice and/or actions have been consumed or implemented. You need to see your work through this lens. It’s not enough to merely complete that Excel spreadsheet or PowerPoint presentation. You need to think about how these insights could have an impact on your clients or customers. You also need to understand how your organisation generates revenue so that you can make sure that your work aligns with and/or supports those efforts as much as possible. What business is your organisation in? What is your organisation’s value proposition? How can you use this understanding in your daily work? How does the business your organisation is in affect the culture?

Another area for observation is how your organisation is designed. The organisation design speaks to the company’s strategy. Look at your organisation chart, or organogram, and see which departments report to whom. Assess why the company was structured this way. Was it organised in this way to better serve its customers and/or clients? Was it to foster collaboration, creativity and teamwork?

| The different organisational designs are reflections of the organisation’s overall business strategy. As business strategies evolve, so do the organisational model and culture. A matrix organisation [where individuals have a dual reporting relationship, usually to a product manager and a functional manager] may lend itself to a culture of agility, customer focus and transformative mindset.” – Shenece Garner Johns |

From understanding to action

One of the biggest challenges in developing your CQ is to become aware of the extent to which you see the outside world through your own cultural lens. No culture is better than another, so we have to remember that we see life through our own biases. This means that we should constantly take a step back to understand that there are other ways of seeing and being in the world. The goal is not merely to tolerate difference but rather to appreciate, embrace and ultimately leverage it for the impact that you want to have for yourself, your team, your organisation and those that you serve.

Decide whether your cultural beliefs are dealbreakers when you enter a new place of employment. If they are, you might have to remove yourself from that environment and find one that is more aligned with your beliefs. Having said that, also recognise that it is highly unlikely that you will find an organisation that is completely in line with your cultural values. And even if by some small chance you find a perfect fit, there is a likelihood that someone in that organisation will not be a perfect fit culturally. As you’re learning more about your company, you have probably already found – or are about to find – gaps between your own culture and that of your organisation.

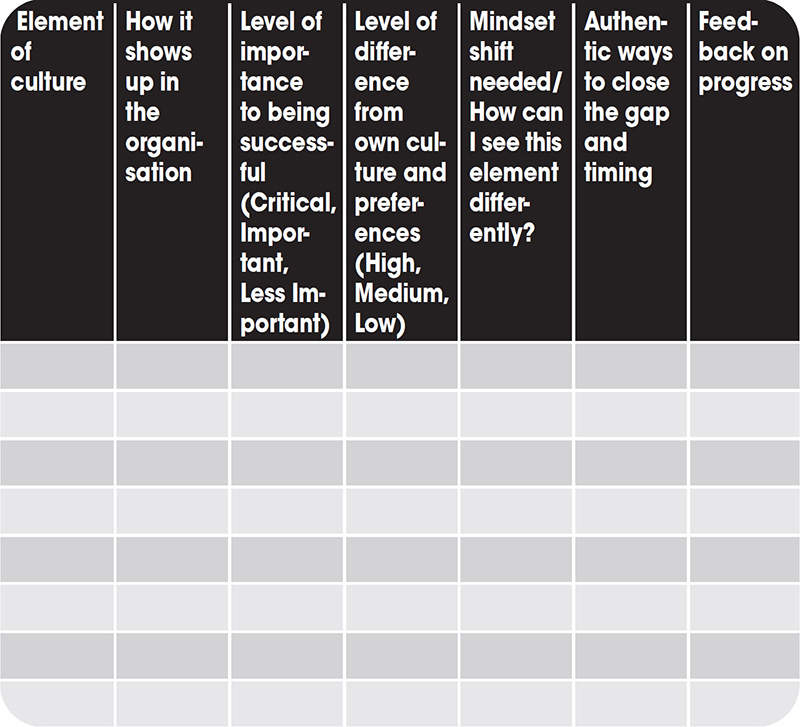

What do you want to accomplish in your current role? What specific areas will you focus on over the next three, six or nine months that will help you be more effective? What are your CQ goals? How critical to your success is alignment with these cultural norms? Remember that these things don’t just happen: you have to create and execute a plan to make it happen. You need to build your awareness and carve out time to increase your exposure to people in the organisation who understand and buy in to the various elements of your organisational culture – especially those elements that you’re struggling with. I’ve created a template that you can use to map out the most critical cultural elements to which you need to adjust in order to be successful in your organisation:

Personal and Organisational Culture Alignment Plan

Try to identify the three to five most critical elements that could make the biggest difference in your performance. Determine how you can see these cultural elements through a different lens or figure out how you can shift your mindset on them. Speak with your mentors, sponsors and manager to find authentic ways that resonate with you to close the gap between your culture and the organisation’s culture. Also ask them for feedback on how you’re progressing and adjust your action plan as necessary. Raising your level of CQ takes time, energy and thoughtfulness, but your personal investment in increasing alignment between your culture and that of your company will be time well spent.