Chapter 2

Get your mind right

Throughout your career, despite your best efforts and intentions, you will undoubtedly experience setbacks. They will come in the form of disappointments, negative feedback, a failed project or a poor performance review. It’s not a matter of if, but when. At no point in your career will you stop being human, which implies that you will never be exempt from making mistakes. When you enter a new corporate environment, you are placed in unfamiliar situations with no blueprint to tell you how to act in them. So, on a daily basis, you learn by trial and error and deal with different personalities, figuring out how best to work with them. Sometimes these new experiences at work will make you feel badly about yourself, thus forcing you to rebuild your self-confidence.

Regardless of how a setback transpires or what it entails, you can never allow it to take you permanently out of the game. Setbacks are hard for everyone, and in my experience, high-achieving folks take these experiences exceptionally hard, exactly because they’re not used to them. It is therefore important for you to realise that you can always decide how you see a given situation. There will always be different strategies within your sphere of influence or control that can help you bounce back. Also, remember that you will be better off learning a difficult lesson – it will help you to never make the same mistake twice. Sometimes you can’t fix situations, but at the very least you can always change your perspective on them. In other cases, you can turn the situation around, create new alternatives to explore, or you can even completely restore what was lost. No matter what happens, push forward and don’t ever give up on yourself completely.

The extent to which you are able to deal with setbacks speaks to your resilience in the workplace. Resilience can be defined as a person’s ability to bounce back from unanticipated changes, setbacks, disappointments or failures. And this is where mindset comes in. Your resilience in bouncing back from setbacks completely depends on your perspective.

Mindset can be defined as your beliefs, thought patterns, perspectives and perceptions on situations in your life. Your mindset affects how you handle adversity, challenges, success and failure.

| I’ve made a lot of mistakes along the way, but I’ve had to make them. I would never change my path and all the things I’ve experienced. Every single mistake has been necessary. Maybe one shouldn’t even call them mistakes. They’re learning opportunities.” – Ipeleng Mkhari |

During my time at McKinsey, a consultant once asked to meet with me. She told me that she had been rated ‘Issues’ in her most recent performance review. (At the company, this was the belowaverage rating and it was not a good sign.) She started off our conversation by saying that no one really cared about her, nobody was willing to help her improve and nobody was invested in her success. Since I was on the Professional Development team, I knew the particular client project she was on and knew some of her team members.

‘Well, what about so-and-so, the partner on the study? How is he?’ I asked her.

‘Oh, he’s great,’ she said. ‘He’s always willing to help me and answer my questions. He definitely thinks that I can turn it around.’ ‘And what about so-and-so, the Engagement Manager?’ I asked. ‘Oh, she’s cool. She’s always very willing to coach me and we get along well.’

‘When you started this conversation, you said no one cared about you or your performance,’ I said. ‘You said that no one was invested in your success. But we’ve just talked about two key leaders on your team that are always willing to coach you so you can turn your performance around.’

She looked at me with an expression of defeat and surprise. ‘Yeah, you’re right.’

From that point, we started talking about how to turn her performance around. We discussed what she needed to do and how she needed to engage her supporters in and outside the project. Nothing about her actual situation – the client project, the leaders on the team, her performance rating – had changed during the course of our conversation. The only thing that was different was her mindset, the way she looked at her situation. She came into our meeting as a victim and left feeling more like a victor. She felt much more empowered because she now had a concrete plan of action.

How this young person moved from the mindset of a victim to that of a victor is a classic example of how important perspective is in a situation. Two people can have two different experiences and outcomes of the same situation depending on how they look at it. Victims blame others, make excuses and deny the role they played in getting themselves into the situation. Victors, however, own their part, take responsibility for what is in their control, and they have a can-do spirit. Victims ask, ‘Why is this happening to me?’, while victors ask, ‘Why is this happening for me? What is the lesson?’

Before I started writing this book, I was in a pretty despondent place in my life. I was feeling powerless and sorry for myself. Then it occurred to me that I’m passionate about, and have many ideas on, helping young people in their careers. Couldn’t I channel that energy into putting those ideas on paper? So that’s what I did . . . and that’s why you’re reading this book right now.

Maybe there are people who never fall into the trap of feeling like a victim. If you’re one of those people, that is awesome. However, the rest of us occasionally slip into the mindset of a victim. The real goal for us is to see how quickly we can talk ourselves out of it. And once we’ve done that, we can start focusing on what we can control or what we can influence.

Control can be defined as the ability to exercise direct influence or power over something, while influence is the power or capacity to affect an outcome in an indirect or intangible manner. Control says, ‘I make the decision’, and influence says, ‘I can persuade the person who makes the decision’ or ‘I can influence the outcome in some way.’ I recently co-facilitated a training event for women with high potential in the workplace. For one of the exercises, we asked the participants to write down everything that was getting in the way of their achieving their professional goals. We asked them to categorise what they’d written into three categories: areas that they had no control over; areas that they had control over; and areas that they had influence over. When the participants in the workshop categorised their challenges, 60 to 70 per cent of their obstacles were either areas that they had control over, or areas that they could influence. Many of the participants had an ‘aha’ moment when they realised that they had a lot more power than they originally thought.

| Your mindset allows you to change, learn and improve.” – Stefano Niavas |

Your mindset is one of those things that you can control. Remember that your mind is your most powerful asset, one that you should guard, manage, grow and challenge on a daily, even hourly, basis. Your behaviour always starts with a thought, so learning how to manage your thought processes about situations and people is critical to your success. This is often where we get tripped up in our careers. We look at situations and people through a particular lens, without challenging ourselves or working on our perspectives. We don’t push ourselves to see other possibilities or entertain the idea that we have blind spots.

| Yesterday I was clever, so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself.” – Rumi, 13thcentury Persian poet, Islamic theologian and scholar |

As you start to examine your mindset and process your experiences at work, your first step will be to identify some of your own problematic thought patterns. Personally and professionally, I’ve experienced – and seen in others – a wide range of unhelpful mindsets. Some of the most common are a lack of self-awareness, not owning your career and doubting your internal net worth (with its counterpart, perfectionism). Then there are also those ‘F’ words that hold us back (failure and fear), what I call ‘checked baggage’, the go-it-alone mentality and the growth vs fixed mindset. We also judge ourselves too harshly when we do not take the long view, and when we measure ourselves by ‘the bubble’ standards and unrealistic timelines. At the same time, we have to contend with our own limiting beliefs and negative self-talk. Many of us suffer from impostor syndrome and we’re paralysed when we don’t know every step. We compare ourselves against others and we forget to bring what isn’t there. Also, as underrepresented minorities, there are certain mindsets that we sometimes struggle with – stereotype threat and learnt helplessness are prime examples – that keep us from showing up at our best. In this chapter, I’ll delve more deeply into each of these topics.

| Mindset is very important. How do I unlearn the fact that I was taught that I was less than growing up? Can I unlearn that idea or am I rather evolving, gaining new insight? People are set up to fail if they’re told to get certain ideas out of their mind, to unlearn ideas such as my hair is nappy or kinky or I’m not beautiful. You want to give people new patterns to think about. Instead: You are beautiful and this is why. Your hair is this way because your ancestors grew up in the southern hemisphere and the curls and texture protected their scalps from the sun. It was a powerful force that enabled them to survive. Other people had straight hair because they were in the northern hemisphere.” – Timothy Maurice Webster |

A lack of self-awareness

The cornerstone of a house is the brick around which other foundational bricks of the house are laid. In your career, your cornerstone is self-awareness. This entails having a balanced perspective on (ie not overestimating or underestimating) yourself, knowing what your strengths are and knowing that you can still develop. The first step in Bill Wilson’s famous 12-step programme is to admit that you have a problem. How can you work on a problem that you haven’t acknowledged? You can’t. Self-awareness is therefore the foundation of your development as a professional and as a person. Without it, you cannot leverage your strengths or address your areas of development.

Lacking self-awareness is similar to driving your car to a destination without knowing your starting point. If you don’t have a balanced, realistic view of yourself, you cannot know how far you have to go or the best path to get there, because you do not know where you’re starting from. I once worked with someone who was famously known to be horrible at execution. Everything she did started late, ended late and was a total chaotic mess. We took a personality assessment as a team and she scored very low in execution. She was surprised. ‘My job is 90 per cent about execution,’ she said to me. ‘How can I be in this job and score so low?’ It took everything in me not to say that I could have told her that for free several years ago. I was shocked that she didn’t know this about herself. It made me wonder: what had she been telling herself all those years about her chaotic projects and meetings? Had she been blaming the environment? The team? Her manager? Had she been honest with herself, she could have addressed those issues much earlier.

We unconsciously tell ourselves stories that aren’t entirely true, both to protect our own egos and to avoid the truth. But we need to grow up, take responsibility and work intentionally on the areas we have not been so great at. When you’re unaware or in denial, you cannot make progress. When I give feedback on one of my company’s self-assessments, the first result I always look at is self-awareness, because it gives me a sense of how much the person will challenge or accept the results. Usually, those with low self-awareness will challenge the results, even though the results are based on their answers about themselves.

Your ability to address the other mindsets that I discuss below is dependent on what you are able to admit to yourself. Our minds are powerful, so we should be truthful about ourselves and continue to grow as people and professionals. The only way to change is if you unpack and connect the dots of your story – the traumas, the triumphs, the defining moments and the key people. Learn to identify the elements of your character that will propel you forward, as well as the ones that could hold you back or overshadow other parts of you. This is the first step in building self-awareness, which is a critical element. It does not happen magically or unconsciously: you have to make a concerted effort.

| You should be able to admit if you’re not good at something and work on being good at it. I had to face myself in the mirror and admit that I wasn’t a great communicator.” – Dr Puleng Makhoalibe, founder, Alchemy Inspiration, and Adjunct Faculty member, Henley Business School |

Not owning your career and managing your performance

When you start working, you have to understand that nobody – not even your manager – is going to care as much about your career as you. You are now the CEO of You Inc, and a CEO doesn’t wait to be given the answers. She proactively seeks what she needs to be successful. You cannot wait for your manager to tell you what you need to do to be successful in the organisation. The onus is on you to understand what is expected of you, get the feedback you need and determine what you need to do to improve your performance.

Determine what you are being evaluated on and how your current role or task is preparing you for the next opportunity. This means finding out what kind of developmental and learning opportunities are available and determining whether you should take advantage of them. In an ideal world, your manager would proactively provide this information to you, but nine times out of ten this will not be the case. Take ownership of your career and your development and get what you need to be successful.

Doubting your internal net worth

The concept of ‘net worth’ traditionally refers to the amount by which assets exceed liabilities. Within the context of your career, think of your internal net worth as what you are worth as a person when you strip away your qualifications, achievements and labels. These things are not liabilities, but they are, however, external to you. Much like any asset or liability, your qualifications, achievements and labels may have value today but tomorrow they may be worthless. At the core of you, how much are you worth to you? If you strip away all of these external attachments, how would you describe yourself? Who would you be without those?

During my first job I questioned my internal net worth. I had always been labelled as the one with the good grades. In high school, I was in all the honours and advanced-placement classes and was selected as ‘Most Likely to Succeed’. I received a full scholarship plus room and board for university and graduated cum laude from the university honours programme. I had always done well in school, with a few notable exceptions (honours chemistry and honours pre-calculus might have been the death of me). I felt that doing well was the only option for my destiny. Doing well wasn’t just something I did – it was who I am. It was in my DNA.

The only reason I accepted my first job offer was because the company offered me an annual salary of $32 000 (or R560 000, which seemed like a lot of money in 1998), free parking, free benefits, free breakfast and lunch and free dinner if I worked late. I wasn’t certain about what my job entailed, but it was a reputable company that paid well enough for me to live on my own. That was all I cared about at the time. It turned out that my role was to be a systems tester for the company’s proprietary benefits administration system. It’s no surprise that I didn’t like the job, but the bigger surprise for me was that I was not the best at it. On top of that I also walked around looking like I didn’t like my job.

One day, my manager called me into her office. ‘Your performance is not what we would expect,’ she said. ‘If you don’t straighten up, I’m going to have to put you on a PDP (Professional Development Plan – a list of performance expectations) and you’ll have 30 days to turn your performance around. Otherwise we’ll have to let you go.’ This was the ultimate wake-up call. How could this be? If I wasn’t doing well, what was I worth? If I wasn’t top of the class, what value was I adding to the world? But the deeper question for me was this: if my identity was achievement, who was I if I wasn’t doing well? Who would I be without my achievements and my labels?

This was my first big lesson in the importance of managing how I was perceived at work. I don’t remember my work being that poor, but I realised that when people saw me looking unhappy, they put me under a microscope and they questioned my work. I had a come-to-Jesus moment when I realised that no matter how much I hated my job, I had bills to pay and I needed to keep my job until I could find something better. I decided to follow the ageold adage ‘fake it till you make it’. I started walking around with a smile (albeit fake) and my manager never had that conversation with me again. I also had to start answering my deeper questions about my self-worth. Around this time I started attending a new church and came to understand my worth in God’s eyes and from a spiritual perspective. This helped me place my worth and value in something other than achievement. While this approach worked for me, you have to determine what works best for you. It is imperative that you find something – besides achievements – in which to root your value.

This experience showed me that I have value and self-worth even if I never achieve another thing. I realised that I don’t have to be doing, achieving, adding more qualifications and living up to labels in order to feel worthy. The very fact that I take up space on Earth means that I have value; I add value by merely being. This is not to say that achievements and qualifications aren’t great: we salute others and ourselves when we accomplish milestones. But our worth is not dependent on them. They merely add to the magic, light and beauty that is already there.

A friend of mine in South Africa runs a modelling agency, for which I teach a confidence class. During my classes, I demonstrate an exercise that I saw somewhere on YouTube. It goes like this: I take out a ‘R20’ note and ask the participants how much it is worth. They say ‘R20’. Next, I crumple up the money in my hand and ask them again. Again, they answer R20. Then I drop the money on the floor and step on it. I ask them how much it is worth and they repeat, ‘R20’. Even if I say that the money in my hand is worth R10, we know that the money is still worth R20.

The R20 in the exercise I just described represents your self-worth. No matter what you do or don’t do, no matter what anyone says or does to you, you still retain your value. It is important for you to have a high internal net worth because when your identity is attached to achievements or labels, your emotions and self-worth fluctuate with every piece of positive or negative feedback. This type of mental volatility makes you an ineffective individual contributor, an unpredictable team player and, eventually, a very insecure leader. It doesn’t mean that you cannot get upset about feedback that you do not agree with. What it means, however, is that you do not doubt your value as a person, together with your ability to learn, to do well and to add value to the people around you. I also believe that when you have a low internal net worth, other people pick up on it and treat you according to the value you have placed on yourself. Another gauge of your self-worth is your relationships. If you are someone who allows others to misuse, abuse, disrespect or dishonour you, you have to ask yourself: ‘How much do I value myself if I allow people to treat me this way?’

| I’m not tied to what people think of me – to the titles, the money. I’m not tied to that because I have a higher purpose.” – Tina Taylor |

Interestingly enough, Sharon Martin, a US-based psychotherapist and author, believes that perfectionism can be rooted in the idea that one’s self-worth is based on achievement. Martin espouses the idea that perfectionism can be said to have its roots in households where, either intentionally or unintentionally, perfection is set as the standard. I grew up in a household where, in my mind, there wasn’t much room for error. I remember the first time I accidentally broke a dish as a child. It wasn’t a fancy dish – just a run-of-the-mill, everyday cereal bowl. I thought my life was over and that the earth was going to open up and swallow me whole.

The more I reflect on the role of perfectionism in my own life, the more I realise how debilitating it has been. It has kept me from taking risks and sometimes even from moving forward. Mistakes I had made caused me to beat myself up for days or weeks. When others would make what I deemed ‘silly’ mistakes, I would comfort them, tell them that it was okay and that they would do better next time. But if I made the same mistake, I would criticise myself no end. Why was it okay for others to make mistakes but not me? Part of me thought that I was too good to make mistakes. Boy, was I wrong!

I once had an e-commerce business and it took me months to make the website public, because I was worried there might be mistakes on it. I checked, double-checked and triple-checked everything, and when I finally launched it I still found more mistakes. I realised that the site would never be perfect, because I was never going to be perfect. I had to accept that I’m not superhuman but the same brand as everyone else: the flawed kind. I saw mistakes as catastrophic, as opposed to what they really are: an opportunity to learn and grow. All I could do was apologise for the mistakes, try to make them right and make sure that I put processes in place so that they never happened again.

Many of us are perfectionists. Perfectionism may have helped us to be successful in school, but it may not serve us well in a corporate environment where time constraints and quick turnarounds are the order of the day. From a more practical standpoint, the idea that you can go off into a corner and emerge victorious three hours later with the answer is a fallacy. You become a risk-averse perfectionist who is afraid to make any type of mistake. This fear keeps you from speaking up – out of fear of saying the wrong thing – and makes you miss or almost miss deadlines because you’re always afraid that your work isn’t good enough. And from what I’ve seen, the pressure becomes too great; instead of propelling us forward to greater heights, it crushes us into silence and sometimes even disengagement. Because we feel as though we have no room for error, in our minds it is better to be silent than to be wrong.

Remember that when you are a new employee, you don’t know enough to do it on your own. You need the guidance and input of others. The perfectionist in us doesn’t want to show anyone anything that isn’t perfect, but you might need to work hard to remove your ego from the situation. This is not about looking perfect. This is about getting to the answer as quickly, efficiently and accurately as possible so that you deliver great results for your client or customer.

Avoiding perfectionism doesn’t mean your work should be sloppy or that you don’t have to double-check your work. However, it does mean that after you’ve checked it twice, you should ask yourself whether you should check it a third, fourth or fifth time. How much value are you adding with those additional checks? Is the additional value worth the time you spent on those checks? Did you sacrifice time you could have spent on other projects?

| A leader who has not worked out their self-worth is dangerous to society. They put on a mask of excessive confidence when beneath the surface they are deeply insecure. They see everyone as a threat. They see everything as being in their way. Put together a collective of such leaders who have not worked out their self-worth and you have set up a society for failure and irreparable damage. These kinds of leaders create a system in which it is impossible for followers to emerge in their own selfworth. The leader’s greatest work is not to point out what is wrong in the world and how only they can fix it. It is to fix themselves. We all suffer when leaders do not do their greatest work. The greatest work is internal.” – Rachel Nyaradzo Adams, founder and Managing Director, Narachi Leadership |

The ‘F’ words

| Understand where your fear comes from, so when you dig deeper you can start understanding the history or the circumstances of your fear. And then you break that down and say, okay, so this is why I’m behaving like this. It’s okay to have a bit of fear, but you can’t operate from that place because it’s not healthy. You need to remove those blinkers and you’ll see the world in a different way.’ – Kagiso Molotsi, People Development Manager, Primedia |

Infants only have two innate fears: the fear of being dropped and the fear of loud sounds. All of our other fears are learnt fears, which means that we can unlearn them or, at the very least, overwrite them. At the root of much of our bad behaviour and poor choices is fear. You have to determine what your particular brand of fear is. There are various things we can be fearful of, for example failure, success, rejection and the unknown. It’s important to understand the root of your fear, how it manifests in your life and what your fear(s) gets in the way of. My number-one fear is failure. My fear of failure got in the way of my launching the website for my e-commerce business and learning the lessons I could only learn once I started it. I was also depriving myself of the lesson that I am still worthy, even if I am not perfect. I delayed learning that imperfections are not fatal.

| I would have allowed my younger self to have a lot more fun in life. My life was so structured; I didn’t want to mess up. I felt that I needed to conduct myself in a way that was always appropriate. It’s not as if I missed out on a whole lot of things, but I could’ve enjoyed the moment more, knowing that even if something didn’t work out, it does not mean that I failed.” – Tina Taylor |

Many of us have spent our whole lives trying to avoid failure. We were never given permission or room to fail. Failure was not an option. From a young age, we’ve been told that the bar is high for those of us who have the opportunity to be in certain spaces. We were told that we must not mess up this chance because it will be another hundred years before someone who looks like us will get another chance. Often we only want to go into situations where we know what we’re doing and what exactly we need to do to be successful. We carry a tremendous burden in thinking that we have to be right all the time and that there is no room for failure. But when we do not take risks and embrace the idea that we might fail, we hinder our chances to grow, innovate, push the boundaries, take risks and learn valuable lessons.

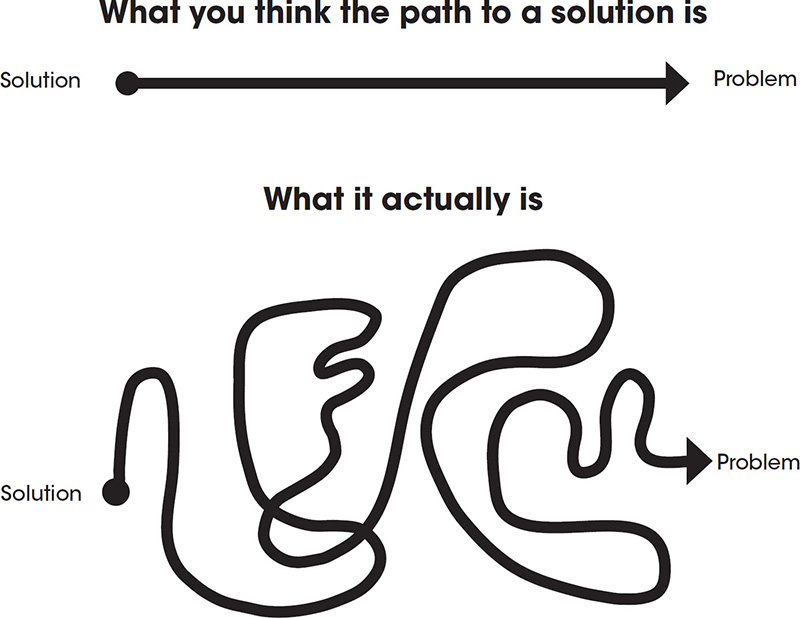

Some of the most successful people have endured great failures. Oprah Winfrey was fired from her newscaster job when she was 24; JK Rowling sent her Harry Potter manuscripts to 12 publishers before getting published. Part of the human contract is that we are fallible. It is a certainty that you will experience failure at some point. But it’s all a question of how you look at it, because failure and risk go together. If you never take a risk, you won’t be able to push the boundary, test a new idea or experience the growth that only comes from stepping outside your comfort zone. However, with every risk there is a chance of success and failure. In every venture, there are degrees of risk that you can take. You could start small by speaking up in a team meeting or asking a tough question. Or let’s look at it another way: let’s say you and your team are trying to solve a problem for a customer. In your mind, the path to the answer is a straight line and you fear your ‘dumb’ suggestion will derail the team. But what if the path to the solution isn’t a straight line? What if it is a complicated series of lines and curves that move forwards and backwards, ultimately leading to the answer? What if your suggestion helps the team get closer to the answer by eliminating a certain option? What if your suggestion helps the team feel more confident about the chosen direction? Then your suggestion, even though it wasn’t the ‘right’ one, helped the team arrive at the ultimate goal. Isn’t that the whole point?

Failure is never final unless you allow it to be. Failure is not who you are, but an event: ‘I failed’, not ‘I am a failure.’ During a talk that Oprah Winfrey gave at Stanford Business School in 2014, she said that failure is just a data point that leads you to your ultimate destiny, which the Creator has designed for you. You are not so powerful that you can interfere with the plan, so relax and focus on the next right step. When I started my online business, I learnt to think in this way. I never knew exactly if my strategies or business decisions would be successful, or how people would react, so I usually started off by trying certain things, learning the lessons, making adjustments and repeating the process. If you have disappointed someone, apologise, make the necessary changes to avoid it happening again, and move forward. Sometimes the lesson you learn is obvious, and other times you have to dig a bit deeper to find it – but it’s always there. Always remember that if you are putting yourself out there, if you are taking risks, and if you are being open and vulnerable, you will make mistakes. But wouldn’t you rather be a person who took a risk and failed than someone who stood on the sideline, wondering ‘what if’?

| We like people who have failed because they’re resilient. They’ve learnt how to put themselves back together, becoming a better version of themselves.” – Stefano Niavas |

Most of us fear ending up in an ‘ultimate failure’ situation. To help consultants explore their worst-case scenarios step by step, I often conducted the ‘what if’ exercise at McKinsey. Here is an example of a typical conversation we would have:

Me: ‘Why aren’t you speaking up in the team problem-solving discussions?’

Fellow: ‘I’m afraid I’m going to say something stupid.’

Me: ‘And what will happen if you do?’

Fellow: ‘I might get a bad rating on the client study.’

Me: ‘And what will happen if you do?’

Fellow: ‘I might get rated “Issues”.’

Me: ‘And what will happen if you do?’

Fellow: ‘I might get counselled to leave [a fancy phrase for fired].’

Me: ‘And then what will happen if you do?’

Fellow: ‘I will be devastated.’

Me: ‘And then what will you do?’

Fellow: ‘I will be depressed.’

Me: ‘And then what will you do?’

Fellow: ‘Eventually I will start looking for another job.’

Me: ‘And then what will you do?’

Fellow: ‘I will start my new job.’

Me: ‘And life goes on.’

When we don’t face our worst-case scenarios, we become paralysed by fear. We think it will be the end of the world, but when we look at it closely, we realise that the earth will not open up and swallow us whole. Life goes on and so will you. If one opportunity does not work out, another one will. And who knows? It might be better than the one you were holding on to so tightly.

| Too many people blame others. You need to ask yourself, what role did I play in the failure? What will I do differently next time? Failure happens and it will happen again. You will fail but how do you recover from it? But if you have a plan in place and you know how to deal with it and grow from it, you will become more resilient over time.” – Acha Leke |

Checked baggage

When I talk about baggage, I’m not talking about suitcases and carry-on bags. Baggage refers to pain or strong negative emotions due to unresolved issues, experiences or traumas from the past. This baggage hinders your ability to live in the present and build healthy relationships. When it comes to your job, you may doubt that you have baggage, especially when you’ve never had a fulltime, professional job. But your baggage may have been created by the experiences and advice of others. The more cautionary the advice, the more it shapes how you feel about the corporate world or employment in general.

For example, many people are told that they shouldn’t divulge details about their personal lives at work. They’re taught that they should maintain a barrier between the professional and personal versions of themselves. While the people who gave you that advice may have had the best of intentions, it may not be relevant for the space you’ve stepped into. In addition, if a family member or friend went through a tough or unfair experience at work, we may take on some of his or her residual bitterness, anger or stereotypes about corporate culture, based on how we saw that person being treated. I’m not saying we shouldn’t take any advice from those around us, but we also can’t take every piece of advice at face value. We need to examine the source and relevance of the information.

Long ago, a Black friend of mine started working at a company I had previously worked for. We kept in touch after I resigned, and one day we were having lunch. I asked her how things were going, and the subject of where she was living came up. She said she was in the process of moving and looking at new homes, but she didn’t want to tell anyone at work because she was afraid they would use it against her. They might think she should have sorted that out prior to starting, she said. She had moved in with her father-in-law after the sudden death of her husband’s mother; after some time, she and her husband had decided to get their own place again. She said that she was always told to keep her private life separate from her work life.

I was surprised to hear my friend’s story because I was familiar with the company. I knew if she gave them the context, they would be willing to give her the time off she needed to go and look at places. It made me wonder why she felt uncomfortable about sharing something so innocuous. Would she be able to share anything deeper? Would she be able to form trust-based relationships at work if she couldn’t even trust her team with this situation? Could her colleagues trust her if she couldn’t even trust them?

Few of our parents ever worked in the type of environments (such as management consulting, investment banks, law firms) that we are working in. The world in which they lived was very different from the one we are in now. For them, it was probably easier to keep the wall up between their private and professional lives. Today, however, many of us are working 12to 14-hour days in collaborative environments where trust is fundamental to sharing ideas, building relationships and achieving business outcomes.

Examine the advice you’ve been given and see if it applies to your current work environment. If it doesn’t, how can you bring your full self – your personality, strengths, interests and areas of development – to work in an authentic way? This will help you to foster mutual understanding between you and your team, and build those relationships through which you may learn the culture, get the necessary sponsorship and advance in the company. Figure out what you’re comfortable sharing to build trust and start there.

When I started at Arthur Andersen, I worked in the human capital consulting practice, and was the only Black consultant on the entire floor. This was quite a contrast from my previous company, so I was in shock. The environment was much more hierarchical and sober-minded, and I felt the gravity of the company and its history in a way that I had not before. At this stage in my career, I still counted the number of Black people in every meeting or conference room. Because of the company’s storied history and because of the demographics of the floor, I felt a tremendous amount of pressure to prove that I (and any other Black person, for that matter) deserved to be there. I felt I needed to represent all Black people and that my failure would reflect poorly on all Black people. If I made a mistake, I thought it might call into question their decision about whether Black people should be in that space at all. My failures were all Black people’s failures; my successes, all Black people’s success. I thought every utterance that came from my mouth had to be profound and insightful. Eventually, this approach backfired: sometimes I didn’t speak up at all. I questioned if my contribution met the very high bar I had set for myself.

My particular brand of baggage was the imagery I had grown up with as a Black kid in post-civil rights Birmingham, Alabama. Those images of police dogs and firehoses being released against protesters; of Governor George Wallace physically barring entry to prevent the integration of the University of Alabama, my alma mater. I remembered the stories of my parents and others who had gone to schools outside their communities due to the racist segregation laws in force at the time. These images were burned into my brain and for some reason were triggered when I started working in a lily-white environment. None of my feelings about this space came from anything anyone had said to me recently. It was all purely me. Eventually, the weight of carrying one billion Black people on my proverbial professional back became too much for me and I realised that the only person I could truly and fully represent was myself.

Interestingly, I realised that my white counterparts didn’t seem to feel the same burden. Not that they weren’t afraid to say something stupid; I’m sure they were. However, they were not fearful of poorly representing – and thus further stereotyping – their entire race. Why should I carry such a burden just because I was born Black? I decided that day that I would always offer my thoughts. Some of them would be good and some of them bad, but at least I knew they were mine. If people wanted to judge all Black people based on what I said, then that would reflect badly on them, not me. I decided that the only way I would be happy, successful and not stressed out was if I took a risk every day to speak my mind, be myself and show up as my most authentic self.

| I was acutely aware of the fact that I’m Black, I’m African, I’m a woman. I walked in with an attitude that was determined to undo any assumptions they had about what any of those three things were. I was going to be that bitchy girl in the office. And it really gave me that confidence. It was not just the confidence to speak up, but eventually also the confidence to relax into my skills and not having to put up that persona. So, my initial space in the first few months was of being a high-walled, inaccessible, angry Black woman. And then I suddenly became this warm, amazing person to work with, a team player who could take any joke. That was a lot of fun. And suddenly I had great relationships with colleagues in other countries across the company” – Refilwe Moloto, strategic and investment adviser and host of Cape Talk’s Breakfast with Refilwe |

The go-it-alone mentality

Many of us are taught to put our heads down, work hard and wait to be tapped on the shoulder and knighted as the chosen one. Our well-meaning parents, aunts, uncles, cousins and family friends give us this advice. We are told that our work will speak for itself and that we will be rewarded for our efforts.

Working in corporate environments for a number of years, I’ve realised that many of us were not taught to collaborate with each other (or anyone else). I know I wasn’t and neither were many people I know. But let me tell you now: every successful person has had a ‘hand-up’ in his or her career. No one has been successful all on their own. The hand-up doesn’t necessarily have to be financial. You might be introduced to someone – perhaps a person you would never have met otherwise – or receive great advice. A handup might be someone allowing you to sleep on her couch for free while you fleshed out your business idea. You could even be mentored or sponsored in a corporate space. Remember that we need other people in order to be successful. Let me say it more forcefully: we can’t be successful without other people. This is an absolute truth, especially in a professional environment. I once had a South African senior executive tell me: ‘Build a network and take people up on their offer to help. You think you need to do it alone or you feel that you’re imposing. You can either put your head down, work hard and hope that someone will appreciate you, or you can look up, look around and see who can help you.’

| I’ve never been the person who wants to do it alone because I’ve never seen the point of that. It’s slow. You just get things done quicker with other people. Even in my team, when I’m developing a strategy, I’ll meet with my team and ask them their opinion. So although I’m driven, I’m driven in the sense that I work through and with other people rather than for myself.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Asking for help doesn’t mean that you don’t have to apply your mind and think about how you should approach your work. You still need to do this because that’s why the organisation hired you. Rather, your manager wants to know how you would solve problems. You need to start with the end in mind and figure out the necessary steps to achieve that end in a timely fashion. Maybe your team has time for you to go off and try to solve the problem yourself, but if they don’t, then understand how you can work faster and more efficiently in that environment, especially if time is a metric by which you are being judged. You have to figure out how to strike the balance between asking for help at the right time and applying your mind to the problem. You don’t want to appear to be a lazy thinker who just immediately asks for help, but you also don’t want to waste time spinning your wheels trying to solve a problem on your own if you can’t.

In order to understand the idea of receiving a hand-up and how it relates to collaboration, let’s unpack the fallacies implied in the idea of ‘putting your head down, working hard and letting your work speak for itself’.

The idea of ‘putting your head down’ implies that you are not aware of what is going on in the company, that you are not building relationships and that you are not assessing the dynamics of power and influence in your workplace. When your head is down, literally, you are unable to assess the non-verbal cues of your colleagues; figuratively, it might mean that you are unaware of any corporate landmines. Even in a corporation you are working with people, so it is important for you to always be aware of what is going on with them.

Although Africa is made up of 54 countries, all with different cultures, languages and customs, the ideas of community and relationships connect them all. But when it comes to our professional lives, we are unfortunately not taught about the importance of connection and relationships. We are taught to put our heads down, to work hard and to be excellent. Where is the connection and relationship-building? Once you pass the interviews and actually get the job, corporate is all about relationships! How did we not incorporate one of our most basic principles? Going at it alone is very un-African!

| Keep my head down. Work, work, work, work. If I just do that, I’m neither thinking of my business strategy nor my brand strategy. If you’re not focused on those things, hard work won’t necessarily get you where you need to go.” – Artis Brown, Fuels Executive, ExxonMobil |

We should also unpack the idea of merely working hard. There is no substitute for hard work, of course; it is true that successful people work very hard. However, successful people also work smart. They figure out what is the most efficient use of their time. They ask: ‘How can I achieve maximum impact? How can I put in the hours on the areas that matter most?’ Successful people don’t just put in the hours; they also figure out what great results look like and they focus their attention there. Working smart implies that you know what you should be doing, how you should be doing it and what great results look like.

When you’ve just been hired, it is almost impossible to know what to work hard on and what ‘great’ looks like in your company. You can learn and develop your skills through e-learning, but remember that most of what you learn will come from your on-thejob experiences and interactions with people.

Someone once told me: ‘Your work does not speak.’ And it’s true: when was the last time you heard a PowerPoint presentation, an Excel spreadsheet or a Microsoft Word document utter one word? I’ll answer that for you: never. Your work cannot speak for itself. In a corporate setting, you have to make sure that your actual voice is heard speaking about what you have done or achieved. When I worked at McKinsey, associates were expected to participate in office extracurricular activities. Those activities could be client-, associateor culture-building activities. The company sees its associates as office leaders who should take ownership of the office, which means they need to contribute to its growth and development. An associate’s participation (or lack thereof) can count negatively against him or her. During one particular review, the committee was discussing a specific associate, questioning her office contribution. They were under the impression that she had not participated in any of the activities. Luckily, the person who presented her case to the committee had a laundry list of activities that she had not only participated in but also conceptualised and led. Had he not presented those, the committee would have left the room with the perception that she had not contributed to the office’s growth and development. It was clear that this associate had gone over and above what was expected of her, but no one (except her case presenter) knew it. This is a perfect example of why we cannot assume that our work speaks for itself. The higher the pressure at your work and the higher the performance standards, the harder you have to work to differentiate yourself. Part of that differentiation process is being able to toot your own horn, talk about your work and create and manage a personal brand that aligns with your work.

Growth vs fixed mindset

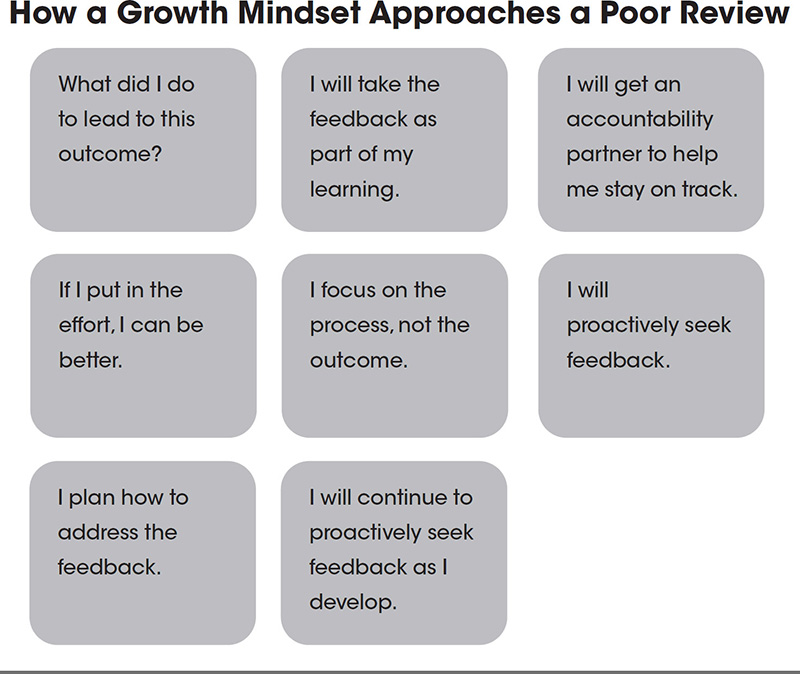

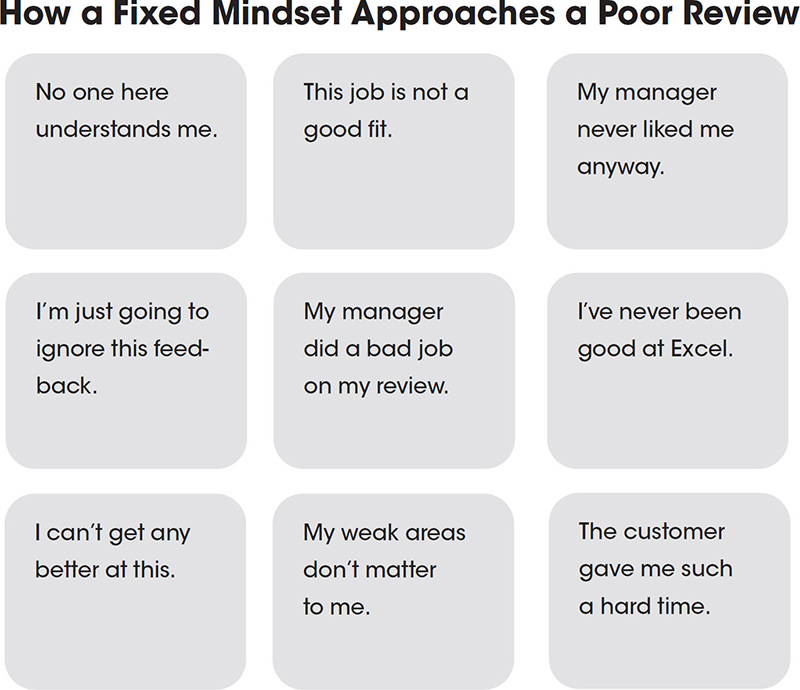

The premise of Carol Dweck’s best-selling book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success is the introduction of two commonly held mindsets: a fixed mindset and a growth mindset. A fixed mindset is focused on outcomes, not processes, and people with this type of mindset believe that intelligence and talent are fixed at birth. They are often afraid of, and avoid, challenges because they see them as threatening. They are concerned that they will fail and their intelligence will be called into question. When they receive negative feedback, they take it personally and can become defensive.

People with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believe that intelligence and talent can increase throughout their lives. Growthmindset people are focused on effort, process and progress, not outcome. They are not afraid of challenges and see them as opportunities to be embraced; they are not focused on how they will look or what the outcome will be. They are focused on the learning, growth and development that will occur as a result of trying. When people with a growth mindset get negative feedback, they are appreciative of the helpful information and use it to grow.

Growth Mindset . . . | Fixed Mindset . . . |

Inquires | Advocates |

Focuses on big picture and then self within that context | Focuses on self |

Seeks and actions feedback | Does not seek or receive feedback |

Takes ownership of learning and development, seeks or creates opportunities to improve | Does not take advantage of or develop opportunities to perform better |

Solution-oriented | Problem-oriented |

Empowered/Victor mindset | Victim mentality |

As a PDM, I often saw individuals who were rated poorly in their annual review. They were then given a certain amount of time to turn their performance around and improve. I know of one individual who managed to lift herself out of the slump by the next review cycle; another person spiralled into another poor rating and ultimately left the firm. They were equal in intelligence and ability, but their mindsets differed. Person A did not see the feedback as fatal. She saw it as a singular event and not an indictment of her ability to be successful at the company. First, she analysed and internalised the feedback she had received, then she took responsibility for the part she played in her rating and met with her mentors to get their interpretation of the feedback. She created an action plan of what she needed to demonstrate to improve her rating, rallying her supporters around her and keeping them abreast of her progress. She had a laser-like focus on the areas she needed to improvement and she worked on them every day. She frequently asked for feedback so she could understand her progress and what she still needed to do to close the gap.

Person B was the opposite. He took the rating as an indictment of his ability to be successful at the company. Going into victim mode, he started to blame others for his poor performance. He was never clear on the essence of the feedback and never took ownership of his role in the poor rating. He did not rally his supporters, nor did he ask his mentors for perspective. He saw every piece of feedback as another nail in the coffin, as opposed to seeing them as data points to help him determine where he should spend his efforts and energy.

When the next review came around, Person A received a totally different outcome from Person B. I believe that Person A had a growth mindset and Person B had a fixed mindset. I’m not saying that Person B did not have some valid points in his outrage or in his desire to blame others, but his mindset didn’t help his case. It’s okay to be upset, but at some point you need to move on and focus your cognitive capacity on turning your situation around.

These two approaches show us that one’s mindset is everything. I’m not saying that your mindset will guarantee good ratings, but, when your time at a company comes to an end, at least you would be able to walk away with no regrets, knowing that you gave it all you had. If you have to leave the company because your performance didn’t improve, at least you know that you’ll be leaving with the respect and admiration of your colleagues. You definitely do not want to say goodbye leaving everyone with a bitter taste in their mouths because of your attitude. Failure or not doing well in the short term is never a waste if you can learn from it. When you learn a lesson, you grow as a person. If you don’t grow, you will continue to experience the same situations – even in different contexts – until you learn that lesson. Always challenge yourself and never get comfortable with the status quo. If you are the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room. It can be scary to continue putting yourself in these situations.

| If you want to excel, you’re going to need someone older than you to help you. You need a mentor. No one can just figure everything out by themselves. I wish I’d had a mentor. I think my life would have been remarkably easier. Now I mentor people who have just entered the corporate world and I see how much easier I’m making their lives.” – Zimasa Qolohle Mabuse |

The trouble with the bubble

Sometimes we think our work environments are all that matters. It’s always good to remember that your work is just one type of environment, and that what matters there may not matter anywhere else. The expectations of that environment might not be realistic, so maintaining perspective on where you work and what matters in the bigger scheme of things is key. When I arrived at Harvard, I knew that I wanted to work in the non-profit space but I was not sure in which area I wanted to specialise. I discovered that people with business backgrounds were bringing their skills to work full-time in public primaryand high-school education. Soon, I was fortunate enough to land a summer internship at Chicago Public Schools, the third-largest public school district in the United States.

While I had a great experience in Chicago, unfortunately Chicago Public Schools was not extending full-time offers for the following year, unlike many of the investment banks or consulting firms that my classmates interned for. I remember how my classmates casually mentioned that they already had offers to start after graduation. I felt depressed. I felt like a loser because I did not have the same level of certainty. But then I reflected more on the situation: in what world do people know where they will be working 10 to 12 months ahead of time? Only in business school, I realised, and business school was not the real world. Business school was a bubble and I remembered not to judge myself by ‘bubble standards’. I had clearly chosen a less traditional route out of business school, so it could take me longer to find a job. But that was okay. It was not catastrophic. I was on my own path.

I also saw the bubble mentality at work at McKinsey. McKinsey is very specific about what matters in its culture – problem-solving, analytics, top-down communication. It was also very important for employees to be familiar with the tools of the trade – it was critical to be able to use PowerPoint and Excel effortlessly. I remember bright consultants coming into the organisation and beating themselves up because they were not as skilful as they thought they were or were expected to be. It was devastating for them. The rules and what mattered at McKinsey became their whole world. To succeed in this environment with these skills, using these specific tools was the only mark of intelligence and success. Nothing else mattered. Consultants felt like failures if they couldn’t be great in this environment.

One day it hit me: the things that mattered so much in this world did not matter in every world. Everyone in the office revered one particular senior partner – let’s call him Mason – because of his influencing prowess and his problem-solving ability. It dawned on me that, unlike Mason, Oprah probably can’t even open Excel; she probably doesn’t know how to create a waterfall graph in PowerPoint. By that environment’s skills and standards, Oprah is not considered successful. But outside that space, she is one of the most accomplished, inspiring, impactful and well-respected people in the world. This is why we have to work hard to maintain a broader perspective on skills that matter and how we define success. This helps us maintain our self-esteem and make peace with the outcome if we are not successful by the organisation’s standards.

Just because you are not good at something in one space doesn’t mean that you’re useless everywhere else. A job fit is like a relationship: sometimes it is just not a good fit even between two awesome people. When you spend all week in the bubble with other bubble people, and socialise with bubble people on the weekend, you end up talking, complaining and thinking about the bubble and its rules all the time. This type of insular existence causes you to lose all perspective, and you begin to believe that the bubble is the world, not a world.

One of the best ways to maintain a healthy perspective is to have frequent contact with people outside your bubble. Non-bubble friends are people who don’t work in your field or industry at all – whatever it may be. You’ll see that they couldn’t care less about your bubble; they are probably completely oblivious to your bubble and its rules. Contact with non-bubble people reminds us that there are other worlds out there. They remind you that not being the best in a particular space is not the end of the world. Make time to engage with the larger world outside to maintain perspective and to keep a healthy view on your company and your job.

Take the long view

Fast-forward and imagine yourself at your 80th birthday: what kind of celebration would you like to have? Who would you like to be there? What would you like to have achieved by then? What do you want people to be saying to and about you? Imagining this helps me to take a long-term view of my career and encourages me to be more vision-oriented. During our careers, we are often presented with many good options and we focus on what is right in front of us. Instead of questioning the options in front of us, we should rather consider whether they will get us closer to what we want to achieve by the end of our lives. Will your choices help you realise your vision? While several options may be good, there is usually one that stands above the rest in that it helps us to achieve our vision for our lives.

This exercise can also help you think about whether there is a disconnect between your life choices and your vision for yourself. In my experience, people often say they want one thing when their actions show the opposite. If you envision having your spouse, children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren at your 80th birthday party, are you at least mindful of the choices and sacrifices that you have to make to realise your vision? Does your current attitude and lifestyle line up with what you say you want? The Japanese concept of ikigai is another lens through which you can view your career. Ikigai translates as ‘a reason to live’, and people use the word to refer to the intersection of what you love doing, what you’re good at, what the world needs and what the world is willing to pay for. Ideally, you want to have overlap between these four elements, so start thinking about the challenges you see in the world and how you can bring your unique set of gifts and motivations to solve this problem – one that the world is willing to pay you to solve.

If you’re missing a certain element, it eliminates the possibility of your achieving the sweet spot between all four elements. Spend time figuring out what problem you can solve with something that really energises you and then spend time getting really good at those skills.

| We hired a millennial on our team, all the right pedigrees in terms of school, everything else. Two months into the job he thought he knew everything and he ended up having an issue with one of the guys on my team. [He talked about] how badly he was being treated. After I broke it down, it was his expectations. I would advise millennials to get a long-term view on their lives. You may not be in the best position today. But don’t look at today’s situation: think and plan long-term and be strategic in what you’re doing. I’m very worried about millennials because many of them are just jumping around from job to job. They go where the grass is always greener.” – Ronald Tamale |

The timeline keeper

When we are in our teens, we often create a timeline of how we think our lives will progress, highlighting the particular milestones we want to reach by certain ages. Maybe you had a timeline for your professional or personal life, or maybe it was a combination of the two. According to my timeline, I had to be married by 25, have my first baby by 27 and my second baby by 29. I was 100 per cent unsuccessful at hitting any of these milestones by the expected ages. On the eve of my 30th birthday, I was single (with no decent prospect in sight) and had no children. I remember feeling particularly down about the fact that my life was not where I expected it to be.

Despite this, I had just graduated from the world’s most prestigious business school. After two very cold years in Boston, I had just started a well-paid job with Deloitte Consulting and I had bought a townhouse in Atlanta four years earlier. My life was great and I was happy about those achievements, but it was tainted by my disappointment at not having ticked those personal-achievement boxes by the ages I had set for myself. Then, one day, I realised that I had made that timeline when I was a 13-year-old who knew nothing about the world, nothing about how my life would unfold and nothing about the challenges I would face. So why was I holding myself hostage to a timeline created by someone who didn’t know anything about anything? Why are you allowing that well-meaning but totally uninformed former version of yourself to drive you to self-pity, angst and anxiety?

I’m not suggesting that you dilly-dally; I’m saying that the idea that you should have accomplished everything by 30 is a myth. Have a plan and work at it, but be open to life. Be open to the unexpected, because some of life’s greatest lessons happen during those unexpected twists and turns. You are still figuring out who you are and what you want to do, and in the midst of it you are likely to make mistakes. A strict timeline leaves no room for mistakes or unexpected adventures. If someone had told me 20 years ago that I would go to Harvard Business School, meet and marry a first-generation Zimbabwean-American HBS alum and live in South Africa for almost a decade, I would have laughed in that person’s face.

The three scariest decisions I have made in my life resulted from events that I couldn’t have predicted, but they are also in the top four decisions I’ve ever made. Years ago, I would have seen these as interruptions that did not factor into my timeline, but today I’m eternally grateful that I did not let that timeline dictate my life choices. My timeline could easily have kept me from some of the greatest adventures and love that I’ve ever experienced.

Are you trying to live up to a timeline that someone else has created for you? Sometimes it might not even be you but the people around you that push you to achieve certain milestones. Family, friends, colleagues and/or members of your religious community might not only push you into a certain career, they can also pressure you in every aspect of your life if you allow them. If you’re not dating anyone, people will ask, ‘When are you going to start dating someone?’ Once you start dating someone, people will ask, ‘When are you going to get engaged?’ Once you get engaged, people will ask, ‘When are you getting married?’ Once you get married, people will ask, ‘When are you going to have a baby?’ Once you have one baby, people will ask, ‘When are you going to have another one?’

While most people are well-meaning, some of them are just nosy and would rather focus on your life than on their own. They are not going to help you pay for a wedding, nappies, childcare or university fees, so why should you let them push you into decisions when you will have to live with the consequences? A critical part of adulting is tapping into what you want and not what society tells you that you should want. It’s figuring out what your dream for your life is, finding the voice to articulate it and having the courage to live it.

When you close your eyes, what do you see yourself doing in 10, 20, 30 or 40 years? Do you see yourself in a high-powered corporate job? Running your own business? At a desk in a fancy office or out on the road talking to customers? Do you see yourself on a stage speaking? Or maybe writing books? I firmly believe that we all know what our dreams are, but to realise them we have to get quiet, spend time alone and drown out the noise of others, as well as our own limiting beliefs, to actually hear what we’ve known all along. Life is not a dress rehearsal, so make sure the life and the career you are living is your own and not someone else’s.

The timeline mentality pushes us to do things personally and professionally outside of when we would naturally do them. Sometimes, out of frustration at not getting what we want when we want it, we jump from job to job and role to role, letting our disappointment turn to anger. Our anger and anxiety then make us say and do things that alienate us from others, which defeats our long-term goals.

I’m not saying that you should wait forever for that promotion or developmental assignment, but in the grand scheme of your life, what is the big deal in waiting another six months or a year? When you look back at your career in 15 to 20 years, will you really regret waiting a couple of months, especially if you know that the performance or development concerns that your manager has are valid? When you have to make an important decision in your personal life or career, fast-forward 20 to 30 years down the line and envision whether you will regret that decision. This approach may not work for every scenario in life, but for those decisions that are time-based, it can be very helpful.

Limiting beliefs

A limiting belief is a false constraint that a person places on herself or others. Examples of limiting beliefs could be: ‘I’m too old to go back to school’, ‘I’m too young to be in management’ or ‘These people don’t want to help me.’ When I was younger, I used to have an either/or mindset. I felt I could have either this or that, but not both. From a very early age, I was steeped in logical, rational, practical thinking. I was not a dreamer: I cared about the here and now and what was directly in front of me. If I only had $5, my thought process was: what can I afford with $5? I didn’t think about what I wanted or needed and how could I make more money to purchase something more expensive. This mentality focused on what I had . . . but that was then.

I believe that my experience at Harvard Business School awakened the dreamer within me. There, we read many case studies about businesspeople who were not bound by their own resources or even the state of the world. For example, Henry Ford (1863–1947), founder of the Ford Motor Company, developed techniques of mass production of automobiles at a time when there were very few paved roads in America and very few people could even afford cars. Apple co-founder Steve Jobs made us believe in and buy a smartphone that we didn’t even know we wanted, and now we can’t live without it. These dreamers were not bound by what was. They dreamed of a world beyond what was in front of them and set out to create it.

Today, I focus on what I want; the how will come later. When I get to the how, I think about how I can get everything that I want, even if those things seem mutually exclusive. Instead of filtering your ideas through all your rational constraints, just say it. You can figure out the rest later. You never know, your idea could be the next iPhone; it could be an idea that revolutionises your life and the lives of others. You’ll never know the impact your ideas might have if you limit yourself based on what you currently have, what you think you can do or what the world currently looks like.

| Something that really holds people back is self-limiting beliefs. There’s a scholarship programme that I encouraged a really brilliant woman to apply for. She said she was going to apply and at the end of the day she didn’t apply. There’s nothing to say that she would have gotten the scholarship had she applied. But when I looked at the pool of candidates, and then I looked at what I know she’d done, she would have been highly competitive. But what guaranteed her failure was her inability or unwillingness to even step out. And when I asked her later on, ‘What made you decide not to apply?’ she just said, ‘I felt like I wasn’t good enough’ . . . It’s really about developing your sense of self and the ability to bet on yourself and your achievements.” – Obenewa Amponsah |

In my second year of high school, I took the PSAT (a pre-college/university entrance exam that matric students in the USA can take) and I did really well on the test. Unbeknown to me, colleges and universities were able to get the PSAT scores of high-scoring students. Soon, I started receiving letters from Princeton, Yale and other top universities congratulating me on my marks and encouraging me to apply. Regardless of what those letters said, I did not believe that I was good enough to get in. In my mind, they were just reaching out to me out of courtesy; there was no way they could seriously want me to apply. I didn’t know anyone who had gone to those types of schools. I just thought people like me didn’t go to those universities. People like me went to local colleges and universities in the city or state, and if you were really stretching it, you went to a neighbouring state, but that was about as far as I thought I could go. I remember putting the letters on my bedside table and thinking, ‘I’ll show these letters to my kids someday.’ It never dawned on me to actually apply. That’s how powerful our minds are. Even when I had physical, hard evidence to contradict my belief about what people like me can accomplish, I went with what my mind told me and not the physical evidence. I didn’t know anyone who had attended that calibre of school, so it seemed out of reach, even though the evidence to the contrary was in my hand in the form of those interest letters.

Throughout our lives, we put many limitations on ourselves, so it’s important to understand and question yourself, your assumptions and the stories you tell yourself about what you can or cannot do. Because I know how my mind sometimes limits me, I always try to take a step back: am I looking at a situation in a limiting way? What assumptions am I making about myself, others, the situation and the possibilities available to me? How can I have it all? How can I make this work? If I don’t have the skills, whose help can I ask for to make this happen? By the time I had to apply for graduate degrees, I had learnt from my limiting beliefs. This time, I decided to go the opposite of safe and apply to business schools that were, I thought, totally out of reach for me. And, thankfully, I was accepted to Harvard. Rather let someone else tell you ‘no’ before you tell yourself ‘no’.

| If you think you’re a three and you come into a meeting as a three, guess what? You’ll get exactly the results that confirm you’re a three! What stops you from thinking that you’re a ten?” – Penny Moumakwa, founder and CEO of Mohau Equity Partners, and former Chief People Officer, Discovery Group Limited |

Negative self-talk

Self-talk is talk or thoughts that you direct at yourself. You spend more time with yourself than with anyone else, so it’s important to assess if what you’re saying to yourself is positive or negative. If someone were to record your self-talk for a week, what would they hear? Would they hear you encouraging or belittling yourself? How you speak to yourself informs how you feel about yourself, which, in turn, informs how you show up in the world. I believe we come to the Earth with perfect confidence and the world slowly chips away at it. We grow up with the opinions of others – things said to us frequently as small children – and we begin to repeat them as if they were our own. As we grow older and unpack those opinions, however, we realise that we are merely regurgitating what was said to us.

I grew up in a household where I received a lot of criticism. Unfortunately, I took on that mindset and directed it towards myself, but in my later years, I have really tried to give myself a break. When it comes to managing your self-talk, sometimes you just have to tell yourself to shut up. You may even need to say it out loud. Interrupt your thought patterns, pause and begin to focus on what is going well, the strengths that you bring and the compassion that you need to extend to yourself as you would to a friend. Remember, if you want to have compassion for others, it starts with having compassion for yourself.

| Confidence is key. I was raised by two parents who affirmed us as children, and who, by the grace of God, had the ability to send us to decent schools at that time in South Africa. The two things they developed in me are confidence and a sense of self. I want to say to millennials: you are brilliant beyond measure. You are worthy. Be patient, but make sure that you know who you are.” – Ipeleng Mkhari |

Self-talk is not about lying to yourself. It’s about maintaining perspective and having a balanced view of yourself and your situation. It’s about focusing on what is within your control and what you can influence. It’s about remembering that the more effort you put in, the more you can improve and increase your likelihood of success. Self-talk is especially about reminding yourself of your strengths and how you can more fully leverage them. It’s about reflecting on all that you’ve learnt in the past and remembering that if you could learn those things, you can learn new things. It’s about remembering how you were able to bounce back from setbacks, disappointments and failures. It’s about learning from mistakes and focusing on what you can do differently next time.

| Most people think I have achieved a lot, but I think I would have achieved more if I didn’t have that small voice that kept on telling me,‘You are not enough. You don’t speak the best English. You come from a rural background. You come from a poor environment. You didn’t go to a private school. You didn’t go to an Ivy League school.’ I think if I had stopped listening to that voice of doubt sooner, and recognised and appreciated my own strengths and achievements, I would have gone further in my career.” – Nomfanelo Magwentshu, Partner, McKinsey & Company, COO for 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee |

Impostor syndrome

‘Impostor syndrome’ is a term coined by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, and describes the belief that you do not belong in, or have not earned the right to be in, certain spaces. People with impostor syndrome fear that others will discover that they are frauds. I often saw this with the fellows in the leadership development programme I managed at McKinsey. I’m not sure if people felt this way because of the mystique around the company brand. Perhaps they could not believe how far they’d come and questioned if they deserved to be there. Maybe they felt intimidated by the environment – one that had been elusive to people who looked like them and came from similar backgrounds.

At Harvard Business School, it took me a while to believe that I had actually gotten in. Their alumni included the who’s who of the business world; it was a place that people like me didn’t attend. I kept waiting for someone to knock on my dorm room door or, worse yet, to come to a class to tell me that I was an admissions mistake and that I needed to pack my bags and get out. This is what impostor syndrome feels like.

Let me tell you: from the many admission interviews I attended for my leadership programme, we never accepted someone that we didn’t think could be successful. Speaking from a purely practical perspective, it would be a waste of everyone’s time and energy to admit someone that we didn’t think could make it in that environment. No one who recruits is there for charity. They are there to employ the best candidates – people who will fit well into the organisation. If a hiring manager is part of the selection process, why would they knowingly hire someone who is not right for the job? It would be completely counterintuitive and self-sabotaging.

Erase from your mind the idea that you are a hiring mistake. Your ingoing hypothesis should be: ‘I am here for a reason. The company selected me because they want me to be successful and they believe I can be successful. I have to put in the work to fully realise the belief they have in me.’

In my experience, one of the reasons people suffer from impostor syndrome is because they compare themselves to their seniors. We compare ourselves to those who have had more time, exposure and experience. As a PDM at McKinsey, I used to conduct onboarding for new hires. I always told new employees that every successful person was in his or her position at some point in their lives. They had a first day too; they weren’t the polished professionals they later became. Just like you, they knew nothing about how the company operates, but after the right experiences, coaching, feedback and effort, they were successful.

Comparing ourselves to our peers can also trip us up. Maybe your colleague is an Excel guru and you aren’t. You might feel inferior or think that you don’t belong there. But keep in mind that you probably have a skill that that person lacks. Remember that no one person possesses every skill needed to be successful at every level in an organisation. Different roles require different skills, and no one usually has everything. The person who is great at Excel is probably horrible at building relationships or presenting ideas. Instead of being intimidated, ask that person to coach you, and then, when the opportunity presents itself, you can coach him or her in your area of strength.

Another fact to keep in mind is that university teaches you the theoretical aspects of your field, but their application can only be learnt at work. In addition, each environment is different, with people doing things differently. For example, PowerPoint might be a widely used tool at your company, used in a very specific way. University will not teach you this: you will have to learn it on the job. The big takeaway is that you need to give yourself a break. Being new sucks, but don’t let it make you doubt your abilities or your drive. Think about all the new things you’ve done up to this point, how you persevered and how you succeeded.

The good news is that being new doesn’t last forever; the bad news is that it rears its ugly head with every new stage in your life. Every new level will expect a new skill set from you. No one would be paying you more money to do the same thing you were doing in your last role. You need to embrace or, at the very least, learn to live with the discomfort of being new. Don’t compare yourself to others, make sure you get what you need and put in the effort to improve. The great thing about barrelling through discomfort is that it builds your confidence.