Chapter 6

Communication is key

Learning how to communicate effectively is probably the most important skill to master in the workplace. Not only does it help you to develop and sustain your personal brand, but it also helps you to maintain healthy professional (and personal) relationships, which plays a critical role in delivering great work. Communication is how we express respect, admiration, frustration, expectations, boundaries, confusion and anger, and get clarification, among many other things. If self-awareness is the cornerstone of your personal and professional development, communication is the brick laid right next to it.

When it comes to your personal brand, you want to be known as a clear and concise communicator. Most of your professional work will be collaborative, iterative and time-constrained in nature, so communication plays a tremendous role in making that back-and-forth process as efficient and effective as possible. Your ability to deliver your work in an excellent way depends on your listening skills but also, importantly, on your ability to clearly and concisely articulate your understanding of the assignment. You should also be able to articulate your questions if you lack clarity about your task. The way you communicate shapes people’s perceptions of you and your level of expertise. Skills such as communicating a sense of urgency, tension between competing priorities, requests for help and appeals to move impossible deadlines account for the difference between a trustworthy, mature team member and someone who isn’t.

A key part of communication is understanding your audience. You want to communicate with people at a level that they can understand and to speak to what is important to them. The way you would talk about a subject with your five-year-old cousin will differ from the way you address your colleague or your grandmother. Your purpose in communicating, especially in corporate environments, should be for your message to be received, not just to speak your mind. Understanding your audience means you have to reflect on what is important to them, anticipate the types of questions or objections they might have and develop your thoughts to address those issues. In a presentation, this also helps you appear more prepared: if you’ve spent time thinking about those questions and preparing fitting responses, the chances of your being caught off-guard are reduced.

Here is an example of how you can think about tailoring your message based on your audience. Let’s say you’re working at an ice-cream shop. During a team meeting you try to convince the owner and the team that another flavour of ice cream should be added to the menu. To meet the needs and address the concerns of each team member, you might want to emphasise the following points. For the sales rep, you could mention that the ice cream has a delicious, dark-chocolate flavour and that it’s dairy-free (something customers have been asking about). For the shop owner, you could say that the ice-cream supplier has agreed to a 60-day payment turnaround (as opposed to a 30-day turnaround). And for the ice-cream-supply manager, you could highlight the fact that the ice-cream supplier is willing to make daily deliveries so the store would not need to keep a lot of the product in stock.

| When you get a big opportunity, you’ve got to know your audience and you’ve got to knock it out of the park. You have to know and believe that you know what you’re talking about, and that you can get their confidence in running your business. That’s fundamental.” – Artis Brown |

One of the first steps in improving your communication skills is to understand what communication is. But let me start by saying what communication is not. Communication is not just about saying whatever comes to mind. It is not about waiting to respond while another person is talking, formulating in your head what your next point will be. Neither is it about winning an argument. It is not about being right. It is not about manipulating, cajoling or strong-arming the other person into agreeing with you. It is also not about saying what you think people want to hear. Instead, communication is about being deliberate about your tone, choice of words and body language so that the other person receives your message and you receive theirs in turn. And this involves the ability to listen. If you are not a great listener, then, unfortunately, you won’t be an effective communicator either.

If you are a great lecturer or speaker, you cannot assume that you are a great communicator too. Remember that communication is supposed to be a dialogue: it is about sharing your perspective and listening to what the other person has to say. It is about being open to new ideas, new perspectives and how the conversation unfolds, and communicating in an authentic way that honours your and the other person’s truth and experience. It is about sharing in a way that strengthens, preserves and grows the relationship and helps you deliver an excellent result. When you are communicating with someone – or even prior to the conversation – make sure to check what your intention is. Is it to be right, to manipulate or to control? Or is it to sincerely hear what the other person is saying and to reach some common ground that will serve as a strong foundation for your relationship and ultimately the impact you want to have? In my experience, many people have never been taught how to communicate effectively, especially when they are in an emotionally charged state or when it comes to sharing thoughts or perspectives that may cause tension or disappointment. To be honest, it’s scary when you’re unsure whether you’re saying the right thing at the right time. You don’t want to upset or disappoint others, but you also don’t want to dishonour yourself by not sharing your truth.

There are a number of techniques that could help you communicate in a way that honours your and your audience’s perspectives. But before we get into those techniques, I want to present another concept: Bruce Tuckman’s ‘forming-storming-normingperforming’ stages of group development. Tuckman believes that the ‘forming’ phase in group development is when a team is first created and each team member is feeling the other team members out and figuring out what the goal is. The ‘storming’ phase occurs when tensions arise and team members are in conflict because of their different communication and working styles. The next phase, ‘norming’, is when teams have learnt to appreciate others’ strengths and differences and the goals and roles are clear. In my opinion, communication is one of the key factors in helping a team find their way through uncomfortable times. If they’re able to do this well, they ultimately come out at the other end with top-notch results (the ‘performing’ phase).

Let us explore the storming phase, as this is where many relationships and teams get stuck. I believe that if we expect to encounter tension within our teams, we would not be so surprised by it and thus not get stuck in it. Consider your sibling or a close relative, someone with whom you share DNA. You have probably grown up with similar values in a similar culture and, from time to time, you have had communication breakdowns or conflict with that person. Doesn’t it stand to reason that you will have conflicts with a colleague, too? Someone who isn’t connected to you genetically and hasn’t grown up with the same values or in the same culture as you? Shouldn’t you spend time understanding how your colleagues think and communicate? Our experiences influence how we see and experience the world, and they are based on all of the facets that make us who we are: gender, race, religion, culture, sexuality, strengths, areas for development, preferences, education and many more. Companies often hire different types of people because of the differences they bring to the table. Unfortunately, though, very few companies show their employees how to successfully navigate the conflicts that arise from those differences. Being able to navigate these is crucial so that we can build relationships and leverage differences in a way that helps the team deliver at an optimal level.

Communication is also one of the key building blocks for creating psychological safety on a team. This term, coined by Amy Edmondson, is defined as a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. Psychological safety, Edmondson argues, creates an environment where people feel accepted, can ask for help, suggest innovative ideas and bring up problems and tough issues without fear of negative repercussions to their credibility or career advancement. As a member of a team, you play a role in creating psychological safety by how you communicate. Researchers are finding that psychological safety may be the most critical driver in building successful, innovative teams.

| One of the things that sets us apart would be communication, and vocabulary plays a big part in communication. For me, communication isn’t about sounding good; it’s not about accents. It’s about having the words to express yourself, whatever your accent is. We underestimate the importance of vocabulary. That’s so important in the working environment, not just for building relationships, but also for presenting your work well. Work requires you to communicate well so that people can appreciate the significance of your work. We could do a lot more to ensure people have the right tools to communicate effectively about their work.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Before we can discuss key topics for communicating and tips on how to do it well, it is critical to examine your current beliefs on communication. You are not a blank slate, and your belief on communication is your starting point for moving forward. Unpacking your approach and mindset on communication will give you insight on what areas of your communication style and mindset you need to leverage as a strength and which ones might get in the way of your being an effective communicator. Do you believe in the value of effective communication? If so, what value do you believe it brings? How would you define effective communication? When you reflect on how your family communicated when you were growing up, think about the communication style of your different family members, as well as the lessons you learnt and habits you picked up from those styles. Think about your usual approach when are you are in a high-stakes conversation. Are you staying present and listening? Or are you mostly focused on formulating your response and merely waiting for an opportunity to respond? If you struggle to stay present, reflect on why that is the case. Examine how important you think it is for you to share your thoughts and feelings on a topic. Do you believe your perspective has value and should be heard? Reflect on whether you believe that courageous conversations are a zero-sum game where you either win or lose. When you go into a high-stakes conversation, are you open to the idea that there might be things you don’t know about the other person’s experience or perspective?

The top three types of courageous conversations to master in your career

Language is important. What we call something – the way we describe something – attaches meaning to it and shapes whether we see it as good or bad. This is especially important when we have courageous conversations. These conversations are often called ‘difficult’, but I prefer to use the word ‘courageous’: when the stakes are high and strong emotions are present, courage is what you need to have the conversation and move forward. Courage is not the absence of fear but the ability to do what needs to be done despite it. When I reflect on my career and the experiences of people I have coached, I can identify three types of conversations that you need to learn to master early on (and even as you advance) in your career: professional delivery conversations, professional development conversations and personal dynamics conversations. Professional delivery conversations relate to the discussions you might have with your manager or colleagues when you deliver work that has been assigned to you. During professional development conversations, you are asking for or receiving coaching and feedback on your performance for your overall development in your career. These types of conversations also occur when you give feedback to others on their performance and development. Finally, during personal dynamics conversations you are discussing your boundaries, desires or the dynamics between you and another person.

All three types of conversation are inextricably linked. When the personal dynamic between you and someone else is unhealthy, it affects others’ desire to want to coach and develop you. This dynamic ultimately affects the quality of what you deliver, which, in turn, affects the team’s ability to deliver the best product. If you are not delivering in the way that others expect, it will affect the level of investment people make in you, thus affecting any feedback and development opportunities you may receive. Below I’ve provided several conversation starters and guidelines under each of the three areas. These are explored in more detail in the scenarios that follow. While they are not exhaustive, these tips can help you to be effective in each area, which will put you on your way to becoming a trusted, reliable team member.

Professional delivery conversation starters

![]() ‘I just received a new assignment.’

‘I just received a new assignment.’

![]() ‘I need help.’

‘I need help.’

![]() ‘I don’t know what the priority is.’

‘I don’t know what the priority is.’

![]() ‘I don’t have the capacity for additional tasks.’

‘I don’t have the capacity for additional tasks.’

![]() ‘I can’t meet this deadline.’

‘I can’t meet this deadline.’

![]() ‘I don’t understand the instructions.’

‘I don’t understand the instructions.’

![]() ‘I don’t agree with a certain course of action.’

‘I don’t agree with a certain course of action.’

![]() ‘I’ve screwed up.’

‘I’ve screwed up.’

Professional development conversation starters

![]() ‘I have been asked to give upward or peer feedback.’

‘I have been asked to give upward or peer feedback.’

![]() ‘I need coaching.’

‘I need coaching.’

![]() ‘I want to ask for a step-up opportunity.’

‘I want to ask for a step-up opportunity.’

![]() ‘I need feedback.’

‘I need feedback.’

Personal dynamic conversation starters

![]() ‘I need to stand my ground on a personal boundary.’

‘I need to stand my ground on a personal boundary.’

![]() ‘I need to address tension in a relationship.’

‘I need to address tension in a relationship.’

As you prepare for any of these courageous conversations, reflect on the tips below so that the conversation can be as fruitful as possible:

![]() What is your intention for this conversation? What outcome is your goal? Is it to be validated? Is it to increase clarity? Is it to get an apology? Is it to stand firm on what you really believe is right? Is it to provide your perspective on the situation?

What is your intention for this conversation? What outcome is your goal? Is it to be validated? Is it to increase clarity? Is it to get an apology? Is it to stand firm on what you really believe is right? Is it to provide your perspective on the situation?

![]() It’s always important to put yourself in the position of the person you are communicating with. What is important to you and the other person? Does what you’re going to say and/or how you’re going to say it consider both sides?

It’s always important to put yourself in the position of the person you are communicating with. What is important to you and the other person? Does what you’re going to say and/or how you’re going to say it consider both sides?

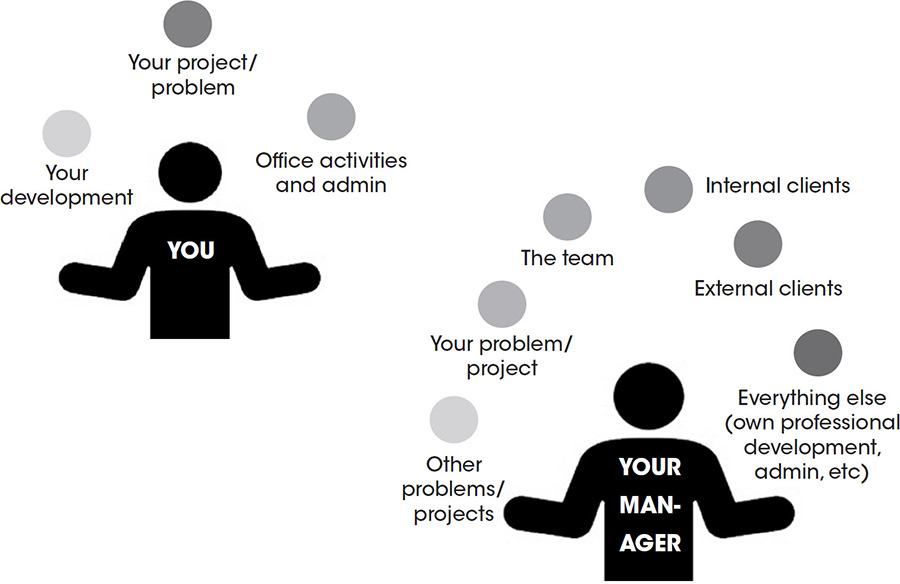

![]() What is the other person juggling professionally? How can you make things a bit easier for them (especially if it is your direct manager)?

What is the other person juggling professionally? How can you make things a bit easier for them (especially if it is your direct manager)?

![]() Have you thought about how to concisely and clearly articulate the key insights or facts from previous conversations?

Have you thought about how to concisely and clearly articulate the key insights or facts from previous conversations?

![]() How can you show that you have thought through what you are saying or asking? How can you approach this person with solutions and not just problems?

How can you show that you have thought through what you are saying or asking? How can you approach this person with solutions and not just problems?

![]() Are you clear about what you’re asking for? What do you need from this person?

Are you clear about what you’re asking for? What do you need from this person?

![]() Are you open to the idea that the conversation might unfold in an unexpected way? Are you willing to state your agenda upfront?

Are you open to the idea that the conversation might unfold in an unexpected way? Are you willing to state your agenda upfront?

Before you have one of these courageous conversations, try practising them with a colleague. Keep in mind the specific communication and conflict style in your organisation. Spend time talking to people who have been at your organisation for some time to understand how to approach these topics. For example, my friend who works at a global management consulting firm says that direct confrontation does not work at her organisation. Instead, she says, you have to use a much more passive, less direct style and vocabulary when addressing an issue with someone else. In her company, saying to someone, ‘You did X and it really upset me’, comes across as overly aggressive. Language that would be more effective would be something like the following: ‘This happened, but what if we had tried a different way of approaching the situation?’ Take these tips and test them to see how you need to tailor your message depending on your environment’s culture.

Here are my tips for how to approach each of the top three courageous conversations:

Professional delivery conversations

Scenario: ‘I just received a new assignment.’ Imagine that your manager has just asked you to complete a new task. Understanding what you need to do, how it fits into the larger picture, the level of quality that is expected, any dependencies between your work and others, and the deadline for the task would all be critical factors. For example, if you are preparing an Excel worksheet, you should ask how it will be used. What sections or pieces of information does your manager expect to see? What format should the report be in, or what template does the manager want you to use? Has the manager (or anyone else) done a similar report before that you could use as a guide? Seven times out of ten, the manager has an idea of what she wants to see and the level of quality she expects. It’s better to start off with that. You should still provide other ideas, but at least you’ll have an idea of what she is aiming for.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions so that you can understand how your work fits into the bigger picture. The earlier in your career you start doing this, the better. It shows that you care about the project as a whole and not just about your part. It shows intellectual curiosity and glimpses of ownership. You should ask your manager when the deadline is and think about the various checkins or reviews that are needed prior to finalising the work. For example, if today is 1 March and you are preparing a report that is due on 31 March for a presentation, your manager shouldn’t see the report for the first time on 30 March. Maybe your manager would like to see a first draft on 8 March and then revised versions on 16 March and 23 March. Be clear with your manager about those deadlines. Schedule the appointments in the calendar now. Those meetings are the time to get your manager’s input, clarify questions you have and make sure you’re on the right track.

Scenario: ‘I need help.’ Your manager has given you an assignment with a deadline, and, after working on it for a bit, you realise that you are stuck. You have several ideas but you’re not sure which direction to take and don’t want to waste time. Don’t spin your wheels too long once you get stuck: time is always a precious resource in a business environment. In this scenario, take time to think about and clearly articulate what you understood the assignment to be, what you’ve done so far, what you’re confused about and what you think the next steps could be. You could even formulate an opinion about which option you like best. Once you’ve done that, approach your manager. It’s important that you demonstrate that you have given it some thought and are not just dumping your problem on her. Tell her that, in the interest of time, you wanted to ask for her guidance early enough to make sure that you’ll meet the deadline. After she has provided guidance, repeat back what she has said and even consider putting it in an email if you sense that your manager may forget what you discussed or if this is a high-stakes assignment. As you can see, this is a much more thoughtful approach than just simply asking for help. The structure with which you approach her communicates your level of thoughtfulness, ownership and concern for your ability to deliver this project on time. You were mature enough to be upfront and admit to not knowing everything.

Scenario: ‘I don’t know what the priority is.’ Over the course of the last two weeks, your manager has given you four different assignments with various deadlines. She has just come to you with another assignment and you realise that you won’t be able to meet all the deadlines. You’re also unsure if she realises that she has given you so many tasks. At this point, you’re not confident about what the priority is. Managers are often juggling several projects, so they are dishing out assignments as they come. Sometimes they are not connecting the dots that they have, for instance, already given you four different assignments with different deadlines. In this scenario, the onus is on you to help her connect those dots and make sure that you both are on the same page. Initiating this conversation protects you from working on the assignments in the wrong order or missing critical deadlines, which can create tension and disappointment. The onus is on you because this is your work and you need to own it. If you don’t deliver according to whatever expectation she has (which she may not even have communicated), it is your reputation and your relationship with her that will be on the line. Since she gave you that first assignment, she may have changed her mind, or the project circumstances may have changed, which may shift the order of priority for the assignments.

In this scenario, before you approach your manager, assess what each assignment entails, where you are with each of the assignments, how much time each will take and what their deadlines are. You may also want to have a view on what you think the order of priorities is and why you think that way, but be open to the idea that your manager might see it differently. Remember that the purpose of this conversation is not to be right but to gain clarity and alignment on the way forward.

What you juggle vs what your manager juggles on a daily basis

I would suggest that you quickly create a one-pager with a table outlining all the information related to your five assignments: it will be much easier for your manager to comprehend your workload if it’s in front of her in black and white. Once you approach her, let her know that you want to discuss all the assignments, and that you want to confirm the priorities with her in light of the additional assignment. Walk through the one-pager that you have created with each assignment and your opinion on the order of priorities. With her guidance, draft a timeline of when things can get done, based on high-priority to low-priority tasks. In this way, smaller tasks could be delegated to someone else who may have capacity. Also, ask her how each of these assignments fits into the overall big picture. This part of the conversation might also help her take a step back and think about the order of priorities. And while you have her attention, confirm the instructions for each task. Once you’ve clarified the order of priorities and any other related aspects, summarise what you’ve discussed in the meeting and follow it up with an email to confirm the conversation.

Scenario: ‘I don’t have the capacity for additional tasks.’ You are extremely busy and now your manager has added another task to your plate. As much as you might want to be the hero in this moment, you know in your heart that it is not humanly possible for you to meet all of these deadlines. It is important that you are honest with your manager; the worst thing you can do is to make a promise and not deliver. It is much better to be upfront about what you are not able to do. It’s important not merely to say, ‘I don’t have time for anything else.’ You always want to be collaborative, open and have a conversation. Express your concern about missing deadlines if you take on another task. Offer other solutions. Could you work on the projects that are furthest along and then enlist the help of another team member to complete the others with guidance from you? Is your manager able to assist? Is there an option to push back the deadline on a few of the assignments? Try to be as solution-focused as possible and let her know that you are willing to put in the extra hours to meet the deadlines, but that you still need assistance. Follow up the conversation with a short email to confirm what was agreed upon.

Scenario: ‘I can’t meet this deadline.’ Your manager has given you an assignment, and at the time the deadline seemed reasonable. However, as you delve deeper into your task, you realise you will not meet the deadline. The most important element in this scenario is timing. Informing your manager at 4:30 pm that you won’t make the 5:00 pm deadline is a very different situation than letting her know at 8:00 am the previous day that you won’t make it. The former situation creates a perception of deception and avoidance. You knew long before 4:30 pm that you were not going to meet that deadline, but either you didn’t want to admit it or you were in denial.

Remember that this type of behaviour is what breaks down trust between you and your manager. It also does not leave her with much time to intervene or explore alternatives and still meet the deadline. Also, you do not know what the knock-on effect of missing this deadline will have on the rest of the project. It is much better to bite the bullet and be honest. Let’s say you recognise at 7:30 am on the day before the deadline that you won’t meet the deadline. Sit down for 30 minutes and assess where you are, what you have left to do and how much time it will take. Reach out to your manager with a sense of urgency as soon as possible. Present your assessment of the situation and highlight that you need either more hands or more time to finish the assignment. Determine which option she is most open to and move on from there. Finally, send her a short email to confirm what you’ve discussed.

| Have excellence and professionalism as standards. If you’re going to be late, be late, but let people know – just to be highly professional in your work ethic. Also, try to always do excellent work even if it means you need to renegotiate the deadline. People need to do their work as if it is an extension of themselves. Does your work represent who you are? Do this with the menial and the sexy work. People will recognise and appreciate that.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Scenario: ‘I don’t understand the instructions.’ Your manager has given you an assignment and you’re genuinely confused about what she is asking you to do. Before approaching your manager, it’s important that you’re able to clearly articulate what you understood from the instructions and the specific elements that are confusing to you, because you don’t want your manager to have to spend time figuring out what you’re confused about. Once you’re clear, sit down with your manager and confirm your understanding of the instructions. Make sure you have absolutely clarity, even if you have to ask two or three times. This is no time to try to save face or be afraid to look ‘stupid’! The quality of your work depends on your understanding these instructions, so when you have your manager’s full attention, make the most of it. Once you have clarity, get to work. If you run up against other points of confusion, try to think them through or research them first (maybe 30 minutes to an hour) and then circle back with your manager for further clarity. Your manager may realise, based on your questions or research, that her directions don’t make sense. Remember that this is an iterative, collaborative process and everyone gains more clarity as the process goes on.

Scenario: ‘I don’t agree with a certain course of action.’ To challenge a manager or the team on a direction can be scary, but remember that you were not hired to simply be a ‘yes’ person (at least I hope you weren’t!). Think about what you’re doing and if it makes sense from your perspective. Now, granted, you are new to this role, this organisation and this industry, so you may not always understand all the nuances. However, sharing your thoughts could make your manager either rethink or reinforce the decision. Since you never know which way it may go, it’s always better to bring up your thoughtful ideas and questions. This is your first lesson in influencing. Influencing is about trying to get someone else to see your perspective and, ultimately, to agree with your suggested course of action. Influencing is not a one-size-fits-all exercise and it is not about manipulating people. It is about packaging a message in a way that resonates most strongly with the other person.

Keep in mind that there are many different techniques to influence others. Some people are influenced by data and would want to see the spreadsheet and the calculations. Some people are influenced by the vision, the emotion and the story behind your idea, while others will agree to an idea if someone they really respect supports it as well. Before you approach your manager, think about what is important to her. What is she trying to accomplish? Talk to people she has worked with to see what their experience was with her and if they can guide you on what techniques work best with her. Regardless of how the manager likes to be influenced, make sure that you are always clear about the facts (including people you think support the idea) and assumptions, and doublecheck whatever calculations you have done that have led you to believe that your chosen course of action is best. How can you approach your manager in a way that resonates with how she thinks and what she wants to accomplish? Also consider how your approach can help her achieve one of her most important goals for the year.

When you’ve done this, consider both the positive and negative implications of both courses of action. Then approach your manager. Give your perspective and the facts, calculations and assumptions that back it up. If she still doesn’t agree with your course of action, maybe make one more push to get her to see things your way. If she still doesn’t agree, you have to stand down and defer to her. She is the manager and ultimately she is the one who will be held accountable for the project. Make sure you fully get behind the decision, and that you support it within the team and to those outside your team. Keep in mind that although you are obligated to voice your thoughts, once the decision is made, your obligation is to support your manager and team. If she does agree with your course of action, make sure you align with her on the next steps and deadlines. Agree to touch base a bit more frequently so she feels comfortable with the progress you’re making with the different course of action.

| When you have an opinion, voice it, but don’t expect it to be followed. And if you make a decision as a team, put yourself behind that decision. That’s what it means to be on a team. Being on a team means you have an obligation to speak your mind, but at the end of the day, you need to get over yourself and deliver with the team because the team is always bigger than you are.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

Scenario: ‘I screwed up.’ At the very bottom of the ‘Being Human’ contract, in the very small print of the Terms and Conditions, is some language around the fact that all of us make mistakes. It is going to happen if it hasn’t happened already. The most important part of screwing up is owning that you screwed up. Don’t try to dress it up. Don’t try to pass blame. I’ve found that people (including me) have so much more respect for people when they own up to their mistakes without equivocation and apologise for the impact of the mistake. Apply your mind to understand the root cause of the problem and make sure your solutions address those root causes and not just surface symptoms. After admitting your mistake, the next step is to address options for fixing it (if it is indeed fixable, because, sadly, some mistakes aren’t). Again, make sure you come with solutions and not just the problems. The next step is to talk about what you’re going to put in place so that it never happens again. The last step is probably the most important: forgive yourself and don’t let it make you doubt yourself.

There is not a successful person in the world who hasn’t made a mistake. I know that because every successful person in the world is a human being (remember, it’s in the T’s and C’s). Apologising can also work for personal-dynamics conversations. Sometimes we say things or step outside our character and we need to apologise. For some people, apologising is a sign of weakness; for others, there is no value in apologising at all. But to hear the words means a lot to people. For me, apologising is a sign of strength and maturity. It shows that you are willing to put ego aside and admit to your mistakes. You don’t hide behind fancy language or excuses and don’t throw other people under the bus to make yourself look better. You own up to what you’ve done, you understand what might have caused your behaviour and you try your darnedest never to let that happen again.

Professional development conversations

Scenario: ‘I have been asked to give upward or peer feedback.’ Just as you are trying to improve your performance, so too are your managers, senior leaders and peers. Your feedback as a junior person is an important data point in their development journey as leaders. Nobody’s perfect, no matter how senior they are or what their title is, and everyone is (or should be) trying to grow. While you may not be able to give technical feedback, you can give feedback on your experience of working with or for that person. You might even have higher EQ, CQ or relationship-building skills than that person, so your feedback could reflect those aspects. Never underestimate the importance of your feedback. I believe that everyone has something to learn from those around them.

You may be asked to provide feedback in a multitude of formats, be it either anonymous 360-degree feedback or in-person feedback (and to the specific manager or peer, or to their managers or peers). This might happen in preparation for an annual or midyear review process. It’s very important to remember that the person you’re evaluating has a career and a reputation that he cares about, just as you care about yours. As such, you should be thoughtful, specific and forward-looking about the feedback you provide. You would not want vague feedback, and neither does this person. Think about specific examples that highlight the strengths and areas of development for this person. At McKinsey, I used to tell consultants that if they are filling out an anonymous feedback survey, they should use language that they would use in a faceto-face scenario. Your language should strike the right balance between honouring your truth and experience, taking accountability and preserving the relationship. Specific phrases that you might want to use are ‘I’ statements (for example, ‘I felt . . .’ or ‘I experienced . . .’) because they help to reduce defensiveness. When you’re giving feedback, structure it as follows: first, state the facts of the situation and the person’s behaviour as you experienced it. Next, explain how the person’s behaviour affected you, others and/or the project overall. Finally, suggest an alternative approach that you believe would be more effective (for example, ‘You did a good job on the report but you can take it to the next level by removing some repetitive information and structuring it differently’).

Much like the balanced feedback you ask for, make sure that you provide strengths and areas for development. Nobody is perfect and nobody is entirely bad. Everyone is great at something, so present that balanced view in your feedback too. If you are in a toxic culture where you feel there might be repercussions for sharing your truth, think very carefully about how much you share and with whom you share it. When you have to give upward feedback, take ownership of your part in whatever situation you find yourself. Here is an example: I once had a manager who asked me to work on a project that was not related to my day job. Nine months later, after many late nights, she told me she had never wanted me to work on the project in the first place. I remember being first confused and then angry. I wanted to karate-chop her in her throat! I am very conscious about how I spend my time, and it infuriated me that I had wasted nine months working on something that wasn’t even related to my primary job. What can people do in nine months? Women spend nine months making new human beings! I could have made a person in that time!

I’m sharing this to show you where my anger took me. As I went over and over the situation in my head, the more upset I became. But I finally had to take a step back, put on my big-girl panties, reflect on the role I played in wasting my own time and accept what I could have done differently. I had been working with this manager for several years at that point and I knew she didn’t always think assignments through. I knew she probably did not understand what type of time commitment was required for this project or how it would take away valuable time from my day job. Before I accepted this assignment, I should have asked more questions. This would have helped her think through the implications of my agreeing to it. I could even have pushed back and said I wouldn’t accept the assignment. So I had to ask myself why I took it on so readily. I realised that a part of me still obeyed authority figures without questioning them. This experience taught me that I needed to do some work on myself in this area. I was not a ten-year-old girl in Catholic school anymore; I was a grown woman and I needed to question certain things. I had the power to ask the questions about how I spend my time.

I could also have chosen to act defensively: I could have blamed her completely. I could have thought, ‘She is the manager and she should think these things through.’ In that case, my upward feedback would have come from a place of anger. But blaming her would not have helped me, especially not if I were to find myself in similar situations in the future. Remember that you cannot control other people and what they do or don’t do. What you can manage is yourself, the questions you ask, the expectations you create and the boundaries you set. This situation was not a waste, because I learnt a valuable lesson. It empowered me and made me less of a victim and more of a victor.

Scenario: ‘I need to ask for coaching.’ Feedback is a reactive exercise. You are finding out how you performed on some task after you have completed the task. Coaching, however, is a more proactive exercise: it is about getting the guidance that you need to do your job well. Everyone needs a coach, no matter how much of a superstar they are. Serena Williams has a coach. Siya Kolisi has a coach. Lewis Hamilton has a coach. I’m going to address two types of coaching: performance and leadership. Performance coaching is about the hard, technical aspects of your role, while leadership coaching is about unlocking your potential so that you can maximise your strengths, identify and address weaknesses and become the most authentic team member, manager and leader.

Early in your career, you focus mostly on honing the hard, technical skills, but as you advance in a company, your leadership skills become more important – how you develop and manage others, how you achieve results through others and how you influence and build relationships with customers and clients. Always have your eye on both aspects, so look for guidance in both areas. In my career, I’ve found that there are two types of coaches at work – those who are natural coaches and those who are not. I consider a natural coach to be someone who provides guidance and gives direction without being asked. This could be someone who makes changes to a document you worked on and then helps you understand how he went from the old to the new version. This person might also coach you on leadership elements – how your word choice, tone and body language are perceived by others. This is a person who recognises your lack of understanding and is energised by growing and developing others. The other type of coach goes from A (the old version) to Z (the new version) without explaining how she got there. This person might not necessarily appreciate your struggle as a new employee, so they would not sense that you need assistance from a technical and/or leadership perspective. Regardless of which type of coach you get, your responsibility is still to get the coaching you need. Come with a hunger to learn and questions to increase your knowledge.

Here are a few coaching questions to ask:

![]() When you start a new assignment or deliverable, what is your approach?

When you start a new assignment or deliverable, what is your approach?

![]() If the coach has made changes to a document you worked on previously: ‘What made you make those particular changes?’

If the coach has made changes to a document you worked on previously: ‘What made you make those particular changes?’

![]() Is there a particular way that I should structure this report/Excel spreadsheet/PowerPoint deck?

Is there a particular way that I should structure this report/Excel spreadsheet/PowerPoint deck?

![]() As I prepare for this client or customer presentation, if it were you, what would you do to prepare for it?

As I prepare for this client or customer presentation, if it were you, what would you do to prepare for it?

![]() How can I be a better teammate? How can I build better relationships internally and externally?

How can I be a better teammate? How can I build better relationships internally and externally?

Coaching doesn’t have to occur within a formal, scheduled time: it can be on the fly. Whenever you are getting guidance on your work, you are being coached.

Scenario: ‘I want to ask for a step-up opportunity.’ Remember that you own your career, so it behoves you to look for opportunities that will challenge you, teach you new skills or expose you to new environments or people. Let’s say that there is an opportunity to work on a project, but it would be a stretch assignment for you, so you would have to ask your manager’s permission. Before you do, think about how you are doing in your current job. If you are not doing well, it is unlikely that your manager will approve your doing additional or different work. Look at this from your manager’s perspective: if you had to manage a person who was not doing well in the job that you hired him for, would you trust him with additional responsibilities? Probably not.

Some of you might be thinking: ‘But, Carice, there are elements of my job that I really hate.’ It’s important that you learn this lesson now: no matter your seniority in a business, there will always be elements of your role that you do not enjoy! I’m sure Aliko Dangote, Oprah Winfrey, Patrice Motsepe and Mo Ibrahim also have elements of their jobs that they don’t like. Learn to see the bigger picture of your work: it will help you get through it. For example, you’re working on a spreadsheet and you hate Excel with every fibre of your being. Instead of focusing on your loathing of Excel, think about how your spreadsheet and analysis will be used. Maybe the client or your CEO will make an important decision based on your data analysis. Don’t forget the bigger picture when you are busy with those smaller, irritating tasks: the point is that they represent larger ideals such as commitment and reliability. Dig deep and tap into a reservoir of focus and discipline to do the things that don’t energise you. If you do them well, you will be given a chance to do the things that energise you. Your manager will probably think: if she is willing to give 120 per cent on something that she doesn’t enjoy, what will she deliver on something that she does enjoy?

But the reverse is also true. If your commitment and reliability are only for things you’re interested in, how can your seniors be sure that you won’t lose interest at some point? People want to know that you will consistently show up, no matter what the task or your level of interest. Once, a junior person told me that she had no interest in participating in a client presentation because (and I quote) ‘I have no interest in the content at all.’ I don’t have an issue with someone not being interested in the content; there are times when I am not interested either. However, your lack of interest should not prevent you from carrying your fair share of the team’s weight and doing your very best. If you were the manager, would you want you on your team? Your goal is to be the kind of team member that you would want to manage.

If you want to ask for a step-up opportunity and you’re doing well in your current job, reflect on whether you have the capacity to take on additional work. You don’t want your day job to suffer because of this additional project. But if you have the capacity, volunteering for office projects is a great way to give back to mentors and sponsors, and it can put you on the radar of important people in your organisation. Importantly, reflect on your why: why do you want to do this project, and why now? Are you going to grow a certain skill set? Will you get an opportunity to work with people you’ve wanted to work with for a long time? If you are determined to take on this new project, you need to reflect on what sacrifices you’re willing to make to put in the additional hours to get your day job and your new project done. Will you commit to working late nights or weekends? Will you sacrifice leisure time? Be honest with yourself, because if you are not willing to make a sacrifice, something is bound to suffer – your day job, the new project and eventually your reputation. If you are confident in your performance, your why and your ability to make sacrifices to deliver at a high level on your day job and the new project, then you can approach your manager to have the conversation.

Keep in mind that your manager is going to do her own assessment, so be prepared for a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’. If your manager agrees, step up your communication to reassure her that she made the right decision. Provide more frequent updates on your day job and the new project, because these updates are important if she is not managing the new project. She might have no visibility into the new project, so she could assume that you are falling behind on your day job because of the shiny new project. Communicating before she asks, and especially before she starts to get anxious, is the best way to reassure her. If you don’t need manager approval, you still need to ask yourself all the above questions, and make sure you step up your communications to anyone you are reporting to and/or working with.

Scenario: ‘I need feedback.’ From the start of your career, you want to be 100 per cent invested in owning your career and growing as a professional and a leader. Learning how to ask for, interpret and action feedback is one of the most critical success factors in a professional environment. It is also one of the most awkward, nerveracking parts of working. We all have blind spots when it comes to our strengths and areas of development, which is why it’s critical to get a more objective view of ourselves.

| Seek out feedback and don’t be afraid. In the corporate space I was working in, there were not many Black people. People that are not Black or other people of colour shy away from giving you feedback because they may think that they’re going to hurt you or that you might not take it well. The same goes for women. Early on in my career I used to make the mistake of not seeking out advice or real-time feedback. You’re working on multiple projects during the course of the year. At the end of a project, go to people, ask for feedback and act on that feedback.” – Ronald Tamale |

Feedback gives us insight into how we are perceived and experienced. Sometimes feedback is objective (for example, ‘Your calculation was numerically wrong’ or ‘Your report is late’) and sometimes it can be subjective (for example, ‘I felt you communicated harshly in that meeting’). Nevertheless, all feedback needs to be examined to find the grain of truth in it. If you’ve spent most of your life hearing how great you are, it will be hard to hear that you aren’t doing well or that your deliverable was not up to snuff. The only thing worse than hearing the critical feedback is not hearing it and, unknowingly, disappointing people. When the former happens, you have an opportunity to hear it, understand it and figure out ways to action the feedback and improve. If you don’t, you’ll never be able to improve.

| If your work is an extension of your ego, then you will never handle any form of feedback. But if your work is about adding value and truly making a difference, then feedback becomes your best friend.” – Simon Hurry, Human Dynamics Specialist and Chief Inspiration Officer, PlayNicely |

A common mistake that many people make is to view feedback as a personal attack on them, their abilities and even their likelihood for success. I mentioned the growth mindset in Chapter 2. If you develop a growth mindset, you will be more focused on the process of improving yourself and you will understand that feedback is a key data input to that process. You have limited time, and if you don’t get feedback, you won’t know where to focus your energy in order to improve. For me, I know that if I trust someone and that person believes I can be successful and is committed to my success, they can say darn near anything to me. Because I know this about myself, I try to build trust-based relationships with people whose feedback I need in order to improve. It helps to lower my defences so I can really listen. You need to determine what makes your defences go down or go up.

Sometimes you will get unsolicited feedback, but you should not count on nor expect it. This is your career, your performance and your future, so it’s your responsibility to ask for the feedback. You also have to determine the speed of judgement in the environment you work in. If it’s a slow-moving environment that gives people more time to ramp up, then you can space out your feedback inquiries. However, if you work in a fast-paced environment where people are judged more harshly and quickly, you may want to get feedback more frequently to improve your performance before judgements are made and it’s too late.

Before meeting your manager (or whoever is providing the feedback), consider whether you are open to feedback or if you are just going through the motions so that you can say that you asked for feedback. What is your intention? Are you interested in growth or do you just want to get your ego stroked? Is it to shift responsibility or is it to share your perspective so that your manager is aware of your experience of the situation? If you are not open to hearing what the other person has to say, then don’t even waste your or the other person’s time. Because this is a new space for you, accept that it requires skills that you may not have. Accept that you are still learning and that you might not be the best. Your ego might be a bit bruised in the process, but receiving feedback is the only way you’ll know what you need to work on.

Giving feedback is difficult for the average person; giving negative feedback is even harder. You cannot expect someone to give you honest, constructive feedback when your body language is closed off. You also cannot expect someone to feel comfortable giving you honest, constructive feedback if you are defensive and have a bad attitude. Defensiveness is about shifting responsibility, blaming other people for our mistakes, making excuses or just generally finding ways to preserve our ego and make ourselves look better to other people and ourselves. To help you navigate the feedback process, develop questions that touch on key performance areas. This will also help you drive the conversation to make sure you get clear examples. Those parameters could be quantitative (such as how well you can structure and manage an Excel model) or qualitative (how well you build customer relationships).

Because feedback can be given during a scheduled time or on the fly, be prepared to drive both types of scenarios. Always keep a notebook and pen handy so you can jot down the key insights from the feedback. If you’ve just given a presentation to a client and you’re riding back to the office, ask your manager how he thinks you fared. Always make sure you ask for both strengths and weaknesses. If you are great in one area but completely failing in an area that matters to the organisation, it will affect your or your team’s ability to deliver. Develop that area up to a minimum bar at least so that it doesn’t overshadow your strengths.

In addition to the questions above, ask your manager the following:

![]() Which two or three areas should I concentrate on in the next few months to make sure I am meeting or exceeding expectations?

Which two or three areas should I concentrate on in the next few months to make sure I am meeting or exceeding expectations?

![]() Is there anything else I should have asked you or that you think I should know?

Is there anything else I should have asked you or that you think I should know?

If you work in an environment where people consistently avoid giving negative feedback messages (this is something that you need to investigate), you should formulate questions that are more difficult for people to give soft answers to. Here are a few examples:

![]() If you could start this project over again, would you still pick me for your team? If so, why? If not, why not, and what two or three things could I do to turn my performance around in a more positive direction?

If you could start this project over again, would you still pick me for your team? If so, why? If not, why not, and what two or three things could I do to turn my performance around in a more positive direction?

![]() Would you recommend me to someone else for their team?

Would you recommend me to someone else for their team?

![]() On a scale of one to ten, how would you rate me on [insert two or three key performance areas here] compared to the best person you’ve ever worked with at this role and tenure?

On a scale of one to ten, how would you rate me on [insert two or three key performance areas here] compared to the best person you’ve ever worked with at this role and tenure?

I recognise that these are tough questions to ask and that the answers might not be what you want or expect to hear. I encourage you to choose long-term growth over short-term comfort so you can get the critical feedback that you need for your growth and development.

| I won’t be offended with anything but be as honest as possible about what you loved about my facilitation, the potential that you see that I didn’t tap into, the concerns that you have, and then suggest what I can change. Be as blunt as possible. It will hurt, but it will be worth it.” – Dr Puleng Makhoalibe |

While you receive feedback, be mindful of your body language. A big part of your responsibility in that moment is for your body language to communicate that you are taking in the feedback. Try and make sure your body language is open and relaxed. Are your arms folded? Are the muscles in your face relaxed? Are you asking follow-up questions and summarising the feedback as it is shared, to let the other person know that you are listening and receiving what she is saying to you? Are you jotting down notes to capture the feedback for further reflection later? The more receptive you are, the more comfortable the other person will feel in giving you the feedback. At the end of the day, you are the only one who loses if you make that person uncomfortable.

When you’ve received feedback, decide what it means and what you will do with it. Below, I’ve structured these activities into the three A’s of feedback: assess, apply, adjust.

Assess: Does the feedback resonate with you? What is the impact of your feedback on the team and you? Which parts of it will you take on and which parts will you ignore? This might surprise you, but you do have a choice: you don’t have to blindly follow whatever people are telling you. Decide for yourself if the concerns raised are ones that concern you. If you choose to ignore certain parts, have you thought about the consequences? Also, consider what your priority areas are, and whether your goals are specific enough. Are you focused on the 20 per cent that will give you 80 per cent of the impact? Talk through your goals with your manager, mentor and/or sponsor and ask yourself how you can leverage your strengths even more. What behaviours will you need to demonstrate to convey proficiency in a certain area, and what are some specific steps that you can take to improve in certain areas? How will you know if you have reached your goal? What evidence will support that belief? Once you decide which areas to address and strengths to leverage, document those items somewhere you can easily access and review them on a daily or weekly basis. The more specific and time-bound your goals are, the easier it is to track your progress and the easier it is to map a route to get there.

Apply: Put daily reminders in your calendar to remind yourself every day about the plan you have for reaching your goals. Visually seeing your goals helps you to maintain focus. In the hustle and bustle of everyday professional life, it’s easy to lose sight of your goals. Put weekly or monthly reminders in your calendar to create space for you to reflect on your progress. Get feedback from people to gauge your progress.

Adjust: Is your plan for improvement focused on the right areas based on your progress, your results and the feedback you’ve received? What changes do you need to make? Are you leveraging your strengths enough, and are you using them to address areas of development? Share your focus and progress with your mentors, sponsors and the person(s) who gave you feedback. You want to rally people around you, and you want your tribe to know that you own your development. Your mentors and sponsors have a network and you increase the likelihood of their singing your praises of commitment to others if you share your focus and progress with them. Remember that getting feedback is an ongoing process. As your role changes and your tenure increases, the expectations change, so you have to stay abreast of those as well while making sure that you’re asking the right questions, getting the right feedback and making the necessary adjustments. This is a lifelong, cyclical process of taking your performance to the next level.

| Always ask for feedback. A lot of the young kids think they’re doing a great job. They show up for performance reviews and when we tell them that they’re on a performance-improvement plan, they get blindsided. They don’t care to ask their leaders and their boss,‘How are you viewing my work? Am I on par? Am I above par?’ Put together a 90-day plan and meet with your leader, your direct manager and your manager’s manager to make sure that you have goal alignment. Be very deliberate, strategic and proactive in communication and receiving feedback. Document everything: people have amnesia when it’s convenient.” – Tina Taylor |

Personal dynamic conversations

Scenario: ‘I need to stand my ground on a personal boundary.’ A personal boundary is an aspect of your work or personal life that is important to you that you need to show up in the best way. One of the most important things that work is about is figuring out your boundaries. You have to strike the right balance between your boundaries and the team and its objectives. As a working adult, you have some space to create the work environment that will suit you best. I’ve been working for 20 years and I continue to learn what set of circumstances allows me to show up at my best. A few years ago, I discussed the idea of boundaries with a former Life Healthcare senior executive. I asked him what it took for him to show up in the best way and he said: ‘I need four things to be in flow and ready for challenges: time with my wife and children, physical activity, time spent outdoors and being outside of working doing things that stimulate my brain.’ He went on to say that he also needs to manage who he works with, but added that it ‘only happens as you become more senior and have a greater degree of freedom’. Here are a few examples of personal boundaries:

![]() I am an introvert, so during the day I need time alone away from the team to process my thoughts.

I am an introvert, so during the day I need time alone away from the team to process my thoughts.

![]() Working out on a regular basis helps me stay focused, keep my weight down and reduce stress.

Working out on a regular basis helps me stay focused, keep my weight down and reduce stress.

![]() I am more of a morning person, so I would like to request that I can start early a few days per week.

I am more of a morning person, so I would like to request that I can start early a few days per week.

If managers trust that the work will get done, they are usually not upset if a person sets a personal boundary. Upset usually comes when professional obligations are not met. When I coach individuals who ask my advice on a personal boundary that is important to them, and they want some help in communicating it to their managers, I ask them to think through the following key questions first:

![]() Why is this boundary important to me? Is this boundary a nice-to-have or is it absolutely critical for me?

Why is this boundary important to me? Is this boundary a nice-to-have or is it absolutely critical for me?

![]() What happens if this boundary is not honoured?

What happens if this boundary is not honoured?

![]() What am I willing to sacrifice to maintain this boundary? How does maintaining this boundary affect the team?

What am I willing to sacrifice to maintain this boundary? How does maintaining this boundary affect the team?

![]() Are there elements of the boundary that I am willing to compromise on?

Are there elements of the boundary that I am willing to compromise on?

![]() Do I know enough to deliver on my obligations and maintain the personal boundary?

Do I know enough to deliver on my obligations and maintain the personal boundary?

![]() What can I do to alleviate any fears that I won’t deliver?

What can I do to alleviate any fears that I won’t deliver?

Once you’ve worked through these questions, set up time to speak with your manager. I always advise my coaching clients to use this phrase to communicate the boundary: ‘In order for me to show up and deliver in the best way, I need [fill in the blank].’ There is not a manager in the world that doesn’t want her team members to perform at their best, so this phrasing helps to communicate how important this boundary is for you and how the team benefits as well. If your manager agrees to this boundary, make sure that you deliver and overcommunicate. The more trust you build up, the more latitude you will get. Check in with your manager to make sure you’re meeting her expectations: it is human nature for your manager to assume that the personal boundary is playing a factor in your performance if it is not up to snuff.

Scenario: ‘I need to address conflict or tension in a relationship.’ If there is unaddressed tension in any of your work relationships – be it with a manager, a peer, a client or any other stakeholder – address it. As a junior employee, this type of tension typically has a disproportionate impact on you, your reputation and, ultimately, your work, so it behoves you to step up and initiate a courageous conversation. Because you are so junior, you probably have less of a network and reputation in the organisation than the person you have a beef with. While you are not addressing the mounting tension, that other person is likely to be sharing his side of the story, thus shaping the narrative about you with a larger audience. I don’t want to make this sound easy. It isn’t. If you come from a conflict-averse culture or community, or if it’s just your personality, there is probably an even more intense level of discomfort in addressing these issues. But, as professionals, we have to learn how to do this well. I have never been a person who enjoys conflict, but I realised that it was necessary to develop this skill and make these relationships work. When I first started having these conversations, my palms would get sweaty and my heart would be racing. Over the years, I’ve gotten less nervous and become better at it.

Before we get into tips about preparing for and managing a courageous conversation, examine your present mindset and history with a topic. When I was growing up, I rarely saw people have calm, high-stakes discussions about topics on which they disagreed. I never saw any real resolution come from the conflict and I didn’t have the skills to conduct the conversation in a calm way, so I just avoided conflict altogether. I carried that mindset into my professional career. In addition, I knew that I had a temper, so I could easily go to a place of anger, and I knew I didn’t want to behave unprofessionally. I had many misconceptions about courageous conversations and here are a few of them:

![]() I don’t need to prepare for these conversations; I show up and hope for the best.

I don’t need to prepare for these conversations; I show up and hope for the best.

![]() If the conversation is getting too heated, it’s not okay to take a break and revisit the topic later. I have to power through.

If the conversation is getting too heated, it’s not okay to take a break and revisit the topic later. I have to power through.

![]() I don’t have the right, authority or permission to confront a senior employee about an issue that I have.

I don’t have the right, authority or permission to confront a senior employee about an issue that I have.

![]() The purpose of the conversation is all about being validated and being told that I’m right.

The purpose of the conversation is all about being validated and being told that I’m right.

![]() I always know all the circumstances of the situation and what the person was thinking or intending when they behaved in a way that upset me.

I always know all the circumstances of the situation and what the person was thinking or intending when they behaved in a way that upset me.

![]() I don’t need to have courageous conversations because I just ‘get over it’.

I don’t need to have courageous conversations because I just ‘get over it’.

![]() I don’t have time for these conversations. I’m too focused on getting my work done.

I don’t have time for these conversations. I’m too focused on getting my work done.

![]() My work is more important than my relationships at work. We’re here to get our work done and go home, not make friends.

My work is more important than my relationships at work. We’re here to get our work done and go home, not make friends.

![]() These conversations are a zero-sum game: either I win and he loses or he wins and I lose.

These conversations are a zero-sum game: either I win and he loses or he wins and I lose.

The book Crucial Conversations, by Joseph Grenny, Kerry Patterson, Ron McMillan and Al Switzler, helped me to understand that I had many incorrect perceptions about courageous conversations. It showed me that there are techniques I could implement that would help me to better prepare for – and manage – these conversations. First, examine your feelings about the situation: you have to determine whether your negative feelings are due to what happened or whether something else is bothering you. The last thing you want to do is unleash all of your emotions on someone when the situation with that person only accounts for half of them. The next step is to understand your level of upset, because you don’t bring up every slight or annoyance. It’s important to pick your battles, use your energy wisely and bring up the situations that really matter. One test I use to see if something is really bothering me is noticing if a situation is still on my mind a few days later. In that case, I have to address it. If I’ve forgotten about it, I move on, but if I’m still bothered by it, I ask myself: ‘Have I calmed down enough to have a rational conversation?’ If not, I try to figure out what element of the situation really has upset me. I try to be open to the possibility that there is something that I don’t know, that I misunderstood something or that I am taking an assumption about the person or the situation as fact. Many times, our anger is the result of believing that we know what the other person was thinking or intending. I also think about my role in the breakdown. Was there something that I said or did that could have contributed to the tension in the relationship? As hard as it may be, own your part, because we all play a role.

Once I’ve worked through these thoughts, I prepare for the conversation by asking myself the following:

![]() What is my goal for this conversation? Is it an apology, validation, clarity? What will make me feel it was worth my time and energy to have this conversation?

What is my goal for this conversation? Is it an apology, validation, clarity? What will make me feel it was worth my time and energy to have this conversation?

![]() What assumptions am I making about the other person’s intentions or actions? What don’t I know about this person or the situation? What might he or she not know about me or the situation?

What assumptions am I making about the other person’s intentions or actions? What don’t I know about this person or the situation? What might he or she not know about me or the situation?

![]() Is this a zero-sum game for me? What would a scenario look like in which the other person and I can give up something and get something that matters to each of us?

Is this a zero-sum game for me? What would a scenario look like in which the other person and I can give up something and get something that matters to each of us?

![]() What are all the possible directions (negative and positive) in which this conversation could go?

What are all the possible directions (negative and positive) in which this conversation could go?

![]() How can I focus more on the solution and less on the problem?

How can I focus more on the solution and less on the problem?

Let me expound on the fourth question above. One of the biggest revelations I had about having courageous conversations was managing my own expectations. At McKinsey, we often used the term ‘release your agenda’. I would go into a conversation and would be certain of what the other person was going to say and what the final outcome of the conversation would be. As you know, human beings are quite unpredictable creatures, so those conversations often did not go as I had planned and I would get upset. Once I realised that this was a source of great frustration (and sometimes bad behaviour) for me, I decided to spend time before each conversation imagining and reflecting on a range of possible outcomes. I would also accept that any of these scenarios was likely to happen and that there might also be an outcome that I could not anticipate. If I expected positive feedback, I would imagine the opposite, and if I expected an apology, I would imagine the person not apologising. If I thought I knew exactly what had happened, I imagined the opposite: what if there is information that I was missing? This approach helped me deal with whatever the outcome of the conversation was. The key was to stay open, be present and embrace how the conversation unfolded.

When you are ready to schedule the meeting, tell the person what situation you want to address so that he or she has time to reflect and prepare if they choose to. Send an electronic invitation so that the time is blocked on the calendar, and reserve a quiet place with as few distractions as possible. Once you’ve thought through the logistics, prepare how you want to frame the conversation. How you open the conversation sets the tone, so spend time thinking about your opening statement. You need to open the conversation in a certain and clear way. Below are a few areas to cover. Once you’re in the conversation, go over the first two questions and then check in with the person to make sure you’re aligned:

![]() Indicate your wish to resolve the issue, and frame it as a common goal, a win-win situation. You may say the following: ‘I know we both are committed to making this project a success. Your support and expertise is critical to making that happen, so I want us to work well together. I want both of us to walk away with more clarity about this project and a better understanding of how best to communicate with each other.’

Indicate your wish to resolve the issue, and frame it as a common goal, a win-win situation. You may say the following: ‘I know we both are committed to making this project a success. Your support and expertise is critical to making that happen, so I want us to work well together. I want both of us to walk away with more clarity about this project and a better understanding of how best to communicate with each other.’

![]() Name the situation you want to address: ‘Do you remember this meeting/conversation/email?’

Name the situation you want to address: ‘Do you remember this meeting/conversation/email?’

![]() Describe the facts of the situation: ‘Is this how you remember the meeting? If not, what is your recollection?’

Describe the facts of the situation: ‘Is this how you remember the meeting? If not, what is your recollection?’

![]() Share your emotions/feelings about this issue: ‘I felt . . .’, ‘I sensed . . .’ or ‘My experience was . . .’

Share your emotions/feelings about this issue: ‘I felt . . .’, ‘I sensed . . .’ or ‘My experience was . . .’

![]() Clarify what is at stake: is it performance, quality, project success?

Clarify what is at stake: is it performance, quality, project success?

![]() Identify and explore the role you played in the situation: ‘I realise I wasn’t as clear as I should have been, which left room for ambiguity and misinterpretation’ or ‘Was it something that I said or wrote that upset you?’

Identify and explore the role you played in the situation: ‘I realise I wasn’t as clear as I should have been, which left room for ambiguity and misinterpretation’ or ‘Was it something that I said or wrote that upset you?’

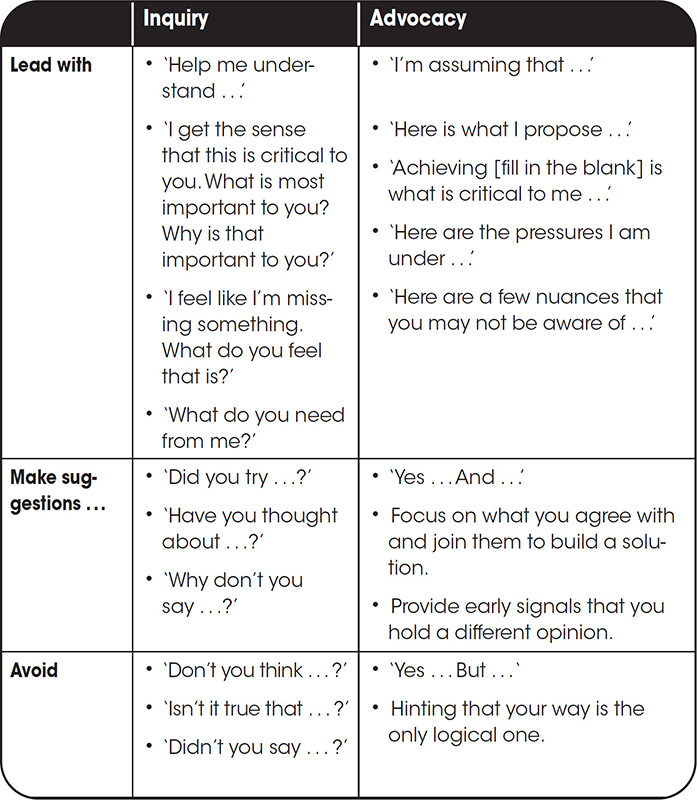

The most important overall tip is to try to strike a balance between advocacy and inquiry. Advocacy is when you’re actively stating your perspective, and inquiry is when you’re asking questions to increase understanding and clarity. While you should share your experience of the situation, you should also be open to hearing what the other person has to say. You want to get their perspective, see if there are any facts that you are missing and clear up any assumptions that you have made. The table below offers tips to reflect on and remember during your courageous conversation:

Remember that you want to be solution-oriented, not problemfocused. At the end of the day, after you hash out the details of who said what when, where and how, you should focus the majority of the conversation on the way forward. What can you and this other person put in place and commit to that will help lessen the likelihood of another discussion like this one and build your relationship?

Problem-focused questions | Solution-focused questions |

|---|---|

• What is the issue? | • What do you want to happen going forward? |

• Why does this continue to be a problem? | • What do you need to make your goal a reality? |

• What happened? | • What do you already have to make your goal a reality? |

• What is the root cause? | • What are some baby steps you could take to create the situation you want? |

• Whose fault is it? | • How far have you come already? |

• What have you tried to address it? | • What lessons have you learnt? |

• Why haven’t you resolved it yet? | • How will you apply these lessons going forward? |

During the conversation, if you feel that it is getting heated or unproductive, it’s okay to press pause and say, ‘I think we need to take a break and revisit this conversation at a later time.’ Remember, the goal isn’t merely to finish: it is to resolve the tension while preserving and building the relationship. It’s better to take a break and calm down than it is to say something you might regret.