CHAPTER 3

EXPLOITING THE POWER OF CORE OPERATIONS

What lies behind you, and what lies in front of you, pales in comparison to what lies inside of you.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Codelco, the world’s largest copper producer, did not choose customer experience as the focus of its digital transformation. It looked inward, transforming its operational processes to increase both its efficiency and its innovativeness.1 The company, which is owned by the government of Chile, employs nearly eighteen thousand people and produces 10 percent of the world’s copper. In 2012, it produced 1.8 million metric tons of copper, generating $15.9 billion in revenue.2

Mining can be a dirty, dangerous, and labor-intensive process. Coordination is difficult because up-to-date information is often only available where the work is happening, whether it is underground with miners, on trucks that move around the mines, or at the machines that process copper ore. Facing challenges around mining productivity, worker safety, and environmental protection, Codelco’s executive team took a hard, strategic look at what the future could bring. The team wanted to transform mining operations, moving from a physical model to one powered by digital technology.

To turn that vision into reality, executives initiated Codelco Digital. The initiative’s goal was to drive radical improvements in mining automation and to support executives in developing, communicating, and evolving a long-term digital vision. CIO Marco Orellana, the leader of Codelco Digital, worked with the executive team, employees, vendors, industry partners, and sometimes even Codelco’s competitors, to innovate operational processes. He said, “Our business in the past was related to physical labor, and today our business is more related to knowledge and technology … We introduced new innovations, new ways of working, and new ways of relating with the people inside the mines.”3

After improving its internal administrative systems, the company shifted focus to transforming the mining process. The first step was to implement real-time mining, that is, a comprehensive real-time view of operations with the goal of improving operational performance.4 In four mines, experts in a centralized operations center coordinate activity remotely, using data feeds from different parts of the mines. Operators capture and share information in real time to tune their operations and to adjust production schedules as needed.

These advances set the stage for more radical change. Immense mining trucks now drive autonomously, arriving at their destinations on time and with fewer accidents than human drivers. The lessons learned from building autonomous trucks have led to autonomous mining machinery. And work processes are changing to take advantage of the possibilities that mobile technology, analytics, and embedded devices make possible. Already, according to Orellana, many workers “don’t travel to the mines. They travel to the [control center in the] city … they apply their knowledge, not their physical strength.”5

The transformation continues, leading to even more radical changes in Codelco’s operations. Integrated information networks and fully automated processes will let the company design future mines differently. The company is moving toward an intelligent-mining model, where no miner may ever need to work in the dangerous underground environment again. Intelligent mining is an important goal, especially after 2010, when thirty-three miners from a different mining company were trapped underground for sixty-eight days.6 Fully autonomous machines, connected through a wide information network, will operate twenty-four hours per day, while being controlled remotely from the central control center.7

But the benefits of digitally transforming mining operations go far beyond safety. Removing humans from underground mines will allow Codelco to design mines to different specifications. After all, if a tunnel collapses on a person, it’s a terrible tragedy. But if it collapses on a driverless truck, it’s not so bad. Human-free mining designs are cheaper and faster to build, with implications for the economics of the company. If Codelco can dig more cheaply and with lower risk, it can exploit huge caches of ore that are not economically feasible today. What started as better process information and driverless trucks is now changing the economics of the entire company.

At the same time that Codelco is automating processes and removing humans from dangerous locations, the company is engaging employees far differently from before. CIO Orellana said, “Our company is very conservative, so changing the culture is a key challenge.”8 Leaders are working to speed execution, become more data-driven in decision making, and increase the firm’s innovativeness. According to Orellana, “We created internal innovation awards to promote new ideas and encourage our workers to innovate.” When workers create an innovation in one mine, Codelco publicizes the innovation, and the workers, across the company.

While not immune to the union-versus-management challenges common in many mining companies, Codelco’s managers and workers are joining together to identify and implement digital opportunities. “We needed more safety conditions for the workers,” Orellana said, “and we needed to create a more attractive business for the new workers who don’t like working inside the mines and inside the tunnels.”9

Codelco executives are now reaching for new frontiers through model-driven management in mining. Instead of making decisions based on past results, they are moving to real-time predictive management. According to Orellana, “This is very challenging because the tools as we know them today, such as ERP, must be adjusted to collect, process, and deploy this new information. We are sure that this ability will become a competitive advantage, allowing us to be even more productive and more efficient than we are today.”

Digital transformation is already paying huge dividends at Codelco. Operational efficiency and safety are increasing steadily. The firm is extending the life of older mines and identifying new opportunities. It is working with vendors from inside and outside the industry to create innovative ways of performing and orchestrating activities. Through vision and execution, this government-owned enterprise is transforming its internal operations, its industry, and, potentially, the nature of mining throughout the world.

Codelco’s story, like that of Burberry, Asian Paints, and Caesars, shows how the first step in digitally transforming operational processes sets the stage for further transformation. We’ve seen this pattern in dozens of companies that use digital tools ranging from basic IT to leading-edge mobile and embedded technologies. Digitally transforming operations requires a strong technology backbone that integrates and coordinates processes and data in the right ways. Then it takes rethinking how you can manage your business better through technology and information. New opportunities follow, ranging from customer experience to operations to business models.

THE POWER OF DIGITALLY TRANSFORMED OPERATIONS

Let’s face it: transforming operations is less sexy than transforming customer experience. Your internal technologies and processes may not be as pretty and polished as what you show your customers. Your best operations people may be more gritty and gruff than your salespeople. But we all know that what’s sexy on the outside isn’t always good on the inside (and vice versa).

In industry after industry, companies with better operations create a competitive advantage through superior productivity, efficiency, and agility. What’s more, strong operational capabilities are a prerequisite for exceptional digitally powered customer experience, as the Burberry and Caesars examples in chapter 2 showed. Yet operational capabilities are far less visible to outsiders than changes in customer experience.

The hidden nature of operations makes it a particularly valuable source of competitive advantage. Competitors can see the outcome—better productivity or agility—but cannot see how you get it. The operational advantage is difficult to copy, because it comes from processes, skills, and information that operate together as a well-tuned machine. Simply adopting a technology or process alone won’t do it. For example, it took US car manufacturers many years to get good at Toyota’s lean manufacturing methods, even though Toyota willingly gave factory tours to its rivals’ executives.10 More recently, traditional companies continue to struggle to adopt the digitally powered methods of online leaders like Amazon.com and Google, although the outlines of these methods are well known. As these cases show, even when competitors start to understand your hidden operations advantage, it may be years before they can make the advantage work for themselves.

Opportunities abound. Companies in every industry and country are already capturing the digital operations advantage. Executives are making better decisions because they have better data. Employees routinely collaborate with people they’ve never met, in places they’ve never visited, and stay connected with the office anywhere and anytime. Frontline workers, armed with up-to-date information, make decisions and creatively resolve operational issues in ways never possible before. Technology, from robots to diagnostics to workflow management, can outperform human workers along dimensions ranging from cost to quality to safety to environmental protection. Other technology is augmenting human labor, improving human productivity, and making work more fulfilling in jobs ranging from customer service workers to attorneys to surgeons. By virtualizing business processes—separating the work process from the location of the work itself, and providing decision makers with the information they need regardless of the source—companies are using technology to truly leverage their global knowledge and scale.

So where do you start? A great first step is to digitally optimize your internal processes. You can digitize core processes, change the way employees work, create real-time transparency, or make smarter decisions. But this should just be a start. The best firms, like many of the Digital Masters we have studied, go well beyond simple process improvements. They see technologies as a way to rethink the way they do business, breaking free of outdated assumptions that arose from the limits of older technologies.

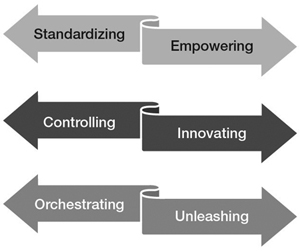

OPERATIONAL PARADOXES OF THE PREDIGITAL AGE

To many executives, improving operational performance represents a paradox of competing goals. Do you focus on the needs of the global company or the needs of local units? On today’s efficiency or tomorrow’s growth? On risk management or on innovation? It may seem that you can optimize one or the other, but not both. Six levers of operational improvement have traditionally created three key managerial paradoxes (figure 3.1). The limits of nondigital technologies and management methods forced managers to make trade-offs on each dimension, choosing “either-or” instead of “both-and.”

FIGURE 3.1

Three operational paradoxes of the nondigital world

For example, the ideas of standardizing and empowering have traditionally been seen as a paradox: artisans empowered to choose their own methods were considered less efficient than workers at production lines, yet the standardized nature of production tasks can make workers far less empowered (and fulfilled) than artisans. Standardization can lead to automation that further deskills workers, reduces wages, or eliminates jobs.11 In a world where computers can do more and more jobs that people once did, what happens to the workers?12

Another pair of operational goals often seen as a paradox is controlling and innovating. Controlling processes tightly—ensuring they run exactly as designed and detecting any variation—can improve efficiency and reduce risk. Yet controlling variation can prevent people from innovating the process in useful ways.13 Employees may be unable to adjust global processes for local customers or to conduct experiments that would improve the processes. On the other hand, loosening controls to enable innovation can open the door to inefficiency or fraud.

A third paradox comes from the need to synchronize steps in complex processes. Paper, offices, and status meetings were the coordinating technology of the twentieth century. That is why, for example, salespeople, field service workers, and police investigators had to visit their offices regularly in person and fill out numerous paper forms. It’s also why so many employees can feel buried in status meetings and e-mail. Traditionally, however, unleashing employees from their offices or workstations made coordinating their activities very difficult.

As a result, orchestrating (which managers want) and unleashing (which employees want) represent another paradox of the nondigital world. In the past, tighter orchestration required tying people closer to the places and methods that did the orchestrating. It created overhead that could reduce peoples’ productivity, restrict their sense of freedom, and sap their energy. Unleashing people or processes from old technology tethers can allow workers to focus on more important activities. But unleashing people can introduce problems in the handoffs between them.

Wouldn’t it be nice if these paradoxes didn’t represent stark either-or trade-offs? When asked whether you want standardization or empowerment (or control or innovation, or orchestration or unleashing), wouldn’t it be nice if you could answer yes?

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION BREAKS OPERATIONAL PARADOXES OF THE PAST

Facing daunting operational paradoxes, managers typically choose to reduce variation and flexibility rather than increase it. They redesign processes to be more standardized, better controlled, and more tightly orchestrated than before. This approach made sense in the days before computers and was the focus of many computerization efforts over the past fifty years.

However, the newest wave of digital technologies is different. Technologies such as smartphones, big-data analytics, social media collaboration, and embedded devices can break the paradoxes of the predigital age. Mobile and collaboration technologies that unleash workers from desks, paper reports, and status meetings can also orchestrate workers more closely. Standardization that removes creativity from some tasks can also empower workers to be more creative in other ways. Technology that imposes strict controls to reduce process variation and fraud can also help you to innovate those processes. Let’s look at how companies are approaching each paradox.

Standardizing and Empowering

Ever since the days of Frederick Taylor, engineers have seen standardization as a way to improve process efficiency. Through time-and-motion studies and other methods, they broke each process into its component parts, standardized each step, eliminated unnecessary activity, and asked workers to follow a precise cookbook of actions. This kind of activity, even in the precomputer age, enabled radical manufacturing innovations such as interchangeable parts and the moving assembly line.

Standardization also makes automation possible. Process reengineering and enterprise resource planning (ERP) efforts of the past twenty-five years have led to dramatic financial benefits.14 Robots have made inroads in standardized assembly-line tasks, working twenty-four-hour days without complaint and making fewer mistakes than humans do. Robots can also make hazardous tasks, such as automotive painting, more efficient by removing the need for worker protection safeguards. As computer capabilities increase, machines will be able to substitute for workers in more and more tasks.15

But standardization can make humans more efficient without replacing them. By providing consistent information on process performance and the status of every order, ERP systems help humans do their jobs better. Similarly, standardized processes in cockpits and pharmacies can help people conduct their work more efficiently and safely without eliminating their jobs.

Let’s look at how companies are managing the standardizing-versus-empowering paradox. It’s sensible to start with standardization, since newer technologies are creating huge opportunities that did not exist before. For example, mobile phones, e-business, and embedded devices produce billions of data points that you can mine for insights on how to standardize and improve your processes. But while some companies continue to drive efficiency through standardization, others are breaking the paradox to both standardize and empower.

Improving Efficiency Through Standardization at UPS

The success of global package delivery company UPS is based largely on standardization and operational efficiency. The company operates in 220 countries, with nearly four hundred thousand employees. In 2012, it served 8.8 million customers and delivered some 4.1 billion items. UPS controls a complex logistical web with millions of possible permutations in service options and delivery routes. Jack Levis, UPS director of process management, explained: “We not only aim to deliver every package on time, but we provide customers with multiple service options to meet their needs. We even allow adjusting of delivery choices while the shipment is in route. Executing this mission means constantly orchestrating orders, adjusting route schedules and following up on package deliveries with a massive fleet of ground and air vehicles.”16

For decades, UPS has been a leader at optimizing its processes. By standardizing its processes, even to the extent of telling drivers how to step off the truck, UPS continually improves efficiency, safety, and quality.17 New data analytics capability is enabling even further optimization. According to Levis, UPS generates “huge amounts of data feeds, from devices, vehicles, tracking materials and sensors. Our goal is to turn that complex universe of data into business intelligence.”18

Route optimization is a key opportunity and a complex challenge, as Levis explained: “We have 106,000 package car drivers globally and we deliver more than 16 million packages daily. When you consider the fact that every driver at UPS has trillions of ways to run their delivery routes, the number of possibilities increases exponentially. The question becomes: how do you mine the sea of data from our sensors and vehicles to arrive at the most effective route for our drivers?”19 Cracking the puzzle can have huge payoffs, as a reduction of one mile per driver per day translates into savings of up to $50 million per year.20

Levis and his team used advanced algorithms to shave millions of miles from delivery routes. The project crunches business rules, map data, customer information, and employee work rules, among other factors, to optimize package delivery routes within six to eight seconds. An optimized route might look very similar to the driver’s normal route—a quarter mile saved here, a half mile there—but the real benefit lies in the accumulated distance saved across thousands of deliveries.

The project is a huge endeavor for UPS, employing some five hundred people. But it generates significant operational advantage. So far, analytics has helped UPS to reduce eighty-five million miles driven per year. The reduction equates to over eight million fewer gallons of fuel used. The systems reduced engine idle time by ten million minutes, thanks in part to onboard sensors that help determine when in the delivery process to turn the truck on and off. This technology alone saved more than 650,000 gallons of fuel and reduced carbon emissions by more than 6,500 metric tons.

Levis said, “We don’t look at initiatives as ‘analytics projects,’ we look at them as business projects. Our goal is to make business processes, methods, procedures and analytics all one and the same. For the front line user, the use of analytics results becomes just part of the job.”21

Breaking the Standardizing-Versus-Empowering Paradox

UPS has generated millions of dollars of savings through standardizing its internal processes. Many other companies are making similar improvements and getting substantial savings. Yet, these changes, while valuable, sometimes focus on only one side of the standardization-empowerment paradox.

Other companies have managed to break the paradox. Even if standardizing can deskill or disempower workers, it does not have to do so. Companies can shift routine tasks to workers who find the routine tasks fulfilling. And if standardizing eliminates some workers, it can empower the others to do more-fulfilling work.

The changes can be small or large. A manufacturer we studied started to standardize, and then automate, many of the tasks in its human resources (HR) function. The company reduced HR staff from more than a hundred to fewer than thirty, while improving employee satisfaction. Employees found it easier to manage routine HR tasks through self-service systems. According to the vice president of HR, the remaining HR employees are happier too. They can now focus on “enlarging manager skills, rather than counting days off.”22 Looking forward, HR plans to hire new employees as the volume of these more-empowered HR tasks grows.

Asian Paints standardized the process of taking orders from the retailers it serves. Formerly, a sales force of hundreds visited thousands of retailers regularly.23 Salespeople took orders for paint and other products, answered questions, and contacted local distribution centers to deliver each order. Orders were then fulfilled by local distribution centers, which operated largely independently from each other.

Seeing an opportunity to improve operations, company executives implemented a single ERP system to manage the whole order-to-cash process, as well as advanced supply chain management capabilities. Implementing the new system required the company to standardize the way it worked, both within and across regions. It also provided better information and efficiency. According to CIO and head of strategy Manish Choksi, “During this period, we built an extremely strong financial and operational foundation for growing the company.”24

Executives soon found another opportunity to standardize processes. Analysis showed that the company could improve customer experience and sales performance by having workers in a centralized call center—instead of salespeople in the field—take routine orders. The change eliminated steps in the process and created economies of scale in order-taking personnel.

As an added bonus, the change also improved service quality. Formerly, customer satisfaction varied across regions and salespeople. But the centralized call center, and its enabling technology platform, changed the situation. For the first time, executives had a single view of all customer-related activity across the company. They could ensure that every retailer got the same level of service, regardless of the retailer’s location. Managers could monitor the performance of each phone representative, providing training and making adjustments as needed. The improvement extended beyond order taking, as the system allowed executives to understand whether some distribution centers were outperforming others, and why.

But what about the people? Workers in the call centers perform highly routinized processes managed by automated systems. Yet, jobs in call centers are considered far better than the jobs many of the call-center workers could have obtained before. And although salespeople lost a key component of their former jobs, eliminating routine order-taking empowered them to do something more. Now, armed with mobile access to the company’s systems, plus training and support from the company, salespeople have transformed from low-skilled order takers to empowered relationship managers. They can give greater service to retailers and be more fulfilled while call center workers are happy to perform routine order-taking.

We have seen this kind of simultaneous standardization and empowerment in many companies we have studied. In online pharmacies, automated production lines do much of the routine work, empowering pharmacists to do more fulfilling tasks: advising patients and managing complex orders, not putting pills in bottles. At Caesars, strong standardization and automation make processes more efficient, but also arm employees with up-to-date information about each customer. Customer representatives can decide to provide an upgrade or a free meal without having to check with supervisors. They even receive information in real time about customers who may need an intervention, and can choose how to serve them best.25

Controlling and Innovating

Codelco’s centralized operations center allows its managers to know, in real time, the status of all activities in a mine. Because information is available in one place, managers can spot potential problems, coordinate activities, and make better planning decisions. Controlling variation makes processes more efficient and safe, while real-time control capabilities allow Codelco to adjust to changes in workload, ore composition, machinery efficiency, and other factors. Yet integrated information also helps Codelco identify areas to target for innovation.

In many industries, automation is particularly well suited to applications that require control. Autopilots make minor adjustments to thrust and direction to keep an aircraft on course. Process automation mixes chemicals in the right quantities and temperatures to optimize reactions and safeguard product quality. Accounting systems ensure that people can only enter transactions for valid accounts and amounts.

Yet, automated control can also reduce innovation and other valuable variations. Overly restrictive systems can prevent employees from giving special perks to their best customers. Tight controls in supply chain systems can force store managers to live with what headquarters tells them, rather than finding the right product mix for their local customers.

As with the previous paradox, the first place to look for opportunities along the controlling-versus-innovating dimension is control. New technologies such as mobile and embedded devices are creating new ways to improve process efficiency, increase product quality, and prevent fraud. But while some companies tend to focus only on control, others are breaking the paradox to control and innovate at the same time.

Controlling Process Quality

Although Asian Paints managed both sides of the standardizing-versus-empowering paradox in its selling processes, it chose to focus on one side—controlling—in manufacturing.26 Paint manufacturing is a low-margin business with many opportunities to make mistakes. The biggest driver of cost is raw materials, which constitute 60 percent of costs. Chemicals must be mixed in the right quantities at the right times, and materials can cause environmental damage if not managed properly.

High growth in paint demand created the need to set up new manufacturing plants every three years. According to Manish Choksi, CIO and head of strategy, building world-class manufacturing plants “calls for a high degree of automation to deliver labor efficiency but also better quality and less waste.”27 Seeing the potential of technology to improve manufacturing, executives opened a 200,000-ton plant in 2010 that was almost wholly automated, followed by a fully automated 300,000-ton plant in 2013. The new plants are completely integrated from an information management perspective. Data from shop floor control systems and warehouses is linked seamlessly to the ERP. This has helped to further sustain the firm’s operational efficiencies. Raw materials flow in from storage tanks, where machines mix the materials and place the finished product into containers in a continuous process. Technicians monitor progress and maintain the machinery, but computers control everything else.

To the company’s executives, the benefits of automation extend well beyond reducing labor costs. Automation has led to greater scalability, better quality, and stronger safety and environmental protections. Fewer workplace accidents occur. The company needs to hire fewer workers for high-turnover factory jobs. Product quality improves because there is less process variation. And with full telemetry on process steps, engineers can troubleshoot production problems faster than before.

Controlling Fraud

New technologies are creating new ways to control fraud. Financial services companies have systems and compliance organizations to detect and prevent unauthorized trading. Credit card companies have real-time automated fraud management operations. But digital technology is opening possibilities in other industries, too.

Employee theft and fraud are widespread problems in firms. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners reported that the typical organization loses 5 percent of its revenues to fraud each year.28 According to the National Restaurant Association, theft for its members accounted for 4 percent of annual food sales, or more than $8.5 billion in 2007. These numbers are significant because pretax profit margins often range between 2 and 6 percent for restaurants.29

For example, in restaurants, opportunities abound for servers to supplement their income through fraud. They can use multiple techniques to steal from their employers and customers, including voiding and “comping” sales after pocketing cash payment from customers and transferring food items from customers’ bills after the bills have been paid. These activities have occurred largely outside management’s eyes, as servers become practiced at varying their techniques to avoid detection.

Recently, a large US-based restaurant chain implemented software to address the problem. The system examines the whole universe of cash register transactions to identify cases of fraud that are so obvious as to be indefensible by servers. Managers can then confront the servers about the activity, armed with specific information about when and where it happened. Corrective actions vary from letting servers know they are being watched to fining or firing them.

A study of the system’s impact in a chain of 392 casual dining restaurants found an average 21 percent decrease in the most egregious forms of theft after implementation.30 Even more interesting, researchers found that total revenue at each restaurant increased by an average of 7 percent, suggesting either a considerable increase in employee productivity or that much more theft is being prevented than the system can detect. Furthermore, drink sales (the primary source of theft in restaurants) increased by about 10.5 percent. This increase is particularly important because the profit margins on drinks in casual dining are between 60 and 90 percent, representing approximately half of all restaurant profits. For restaurant owners, this type of digital control represents an immediate opportunity to increase profits without major investment or process change. For servers, it may represent something else.

The possibilities extend to other contexts as well. For years, governments have used computers to detect signs of fraud in tax returns or equity trading. Now, they are looking in other areas. For example, recent research has identified signals of fraud in automotive emissions inspections.31 Governments can use these signals to target their enforcement operations and reduce corruption.

Breaking the Controlling-Versus-Innovating Paradox

While the benefits of using technology to control process variation and reduce fraud are enormous, technology can also spur innovation. Measuring tightly controlled processes gives companies like Asian Paints, Caesars, and Codelco the opportunity to identify problem areas and improve processes. They can conduct controlled experiments, accurately measuring differences between treated and nontreated groups. Caesars CEO Gary Loveman was once quoted as saying, “There are three sure ways to get fired at Caesars. The first is to steal from the company. The second is to harass someone. And the third is to conduct an experiment without a control group.”32

A restaurant firm is actively conducting experiments in pricing and promotion across a set of franchised booths in sporting and entertainment pavilions. Using digital signage, the company can experiment with bundling and pricing to increase sales. Sellers can change their menus according to whether a baseball game, football game, or concert is happening nearby. Now the company is experimenting with dynamically adjusting prices to shift demand as a result of weather, time of day, and inventory levels. The company shares what it learns in each location so that others can benefit. But the company retests each idea in each new venue to ensure that ideas from Milwaukee will really sell in Miami, and vice versa.

Even more powerful is the experience of Seven-Eleven Japan (SEJ), whose strong, central process controls increase efficiency while also enabling innovation.33 The company has built an information and process platform that connects every store to headquarters and distribution centers in real time. Store managers have the status of every order they have placed, whether it is for hot foods, delivered twice daily; cold food, delivered daily; or hard goods, delivered less frequently. A dashboard in each store shows real-time performance relative to similar periods in the past. Managers know what is selling and what is not, and they can vary their orders accordingly. The managers can even adjust orders on a daily basis, such as ordering more hot foods on days that are expected to be cold and rainy.

SEJ’s strong process controls also enable innovation. The company routinely launches new products and tests them in a sample of stores, getting rapid feedback on product performance. Good products stay, and poor products drop. SEJ also experiments with services such as banking and bill paying that can use the firm’s many retail locations to provide customer convenience.

The company has begun to foster new innovation opportunities at the local level. Store managers are encouraged to make hypotheses about what will sell, and order accordingly. They might see children wearing a certain color, and order accessories in that color. Or they might suggest a new product in light of what customers have been requesting lately. Successful experiments turn into innovations that the company can share across all of its stores. In a company where more than 50 percent of products are new each year, the opportunities afforded by local innovation capability are very valuable.

Seven-Eleven Japan shows clearly how technology can break the paradox between controlling and innovating. The standards and processes that reduce variation can also provide opportunities to conduct experiments that improve the company’s performance. This kind of experimentation on tightly controlled processes is a well-known innovation technique for digital firms such as Amazon and Google.34 Now it is moving rapidly from the digital world to the physical one. It would not be possible without the integrated real-time data that today’s digital technologies can provide. But only companies that take active steps to use information differently can unlock the innovative potential that digital operations provide.

Orchestrating and Unleashing

New digital technologies are unleashing people from the constraints that once bound them. People can increasingly work where they want, at the hours they choose. They can communicate as they wish, with a few friends or hundreds of “friends,” sharing sensitive information easily with people inside and outside their organizations. To many workers, this sounds like freedom. To many managers, it sounds like chaos.

On the other hand, digital technology can synchronize processes more closely. Mobile scanners in warehouses and stores link directly to inventory systems and financial systems, launching requests that span your company and reach into other companies. GPS and mobile phones allow you to track field workers, so that you can schedule them and monitor their performance more closely than ever before. Radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags and sensors on devices provide mountains of information to track devices or monitor processes in real time.

In using these new technologies and data, many companies focus only on the benefits of orchestration. But more is possible. Some companies envision how to break the paradox, unleashing people and processes from constraints while simultaneously orchestrating activities closer together.

Digitally Orchestrating Supply Chains

Digital technologies create many opportunities to orchestrate supply chains better. Channel partners—suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, or customers—can share information on a real-time basis. Proactive supplier collaboration and visibility of raw material flow can improve order quality and reduce sourcing costs. Companies that have digitally transformed their supply chains are racing ahead and reaping huge benefits.

Kimberly-Clark Corporation, a US-based personal and health-care products supplier, built a demand-driven supply chain using data analytics to gain better visibility into real-time demand trends. This capability enabled the company to make and store only the inventory needed to replace what consumers actually purchased, instead of basing its manufacturing on forecasts from historical data. Kimberly-Clark utilized point-of-sales data from retailers such as Walmart to generate forecasts that triggered shipments to stores and guided internal deployment decisions and tactical planning. It also helped the company create a new metric for tracking and improving supply-chain performance. The metric, defined as the absolute difference between shipments and forecast and reported as a percentage of shipments, effectively tracks stock-keeping units and shipping locations. Using this metric, Kimberly-Clark has reduced its forecast errors by as much as 35 percent for a one-week planning horizon and 20 percent for a two-week horizon. Improvements over an eighteen-month period translated to one to three days less safety stock and 19 percent lower finished-goods inventory, with direct impacts for the company’s bottom line.35

Apparel retailer Zara is another example. Zara supports its “fast-fashion” business model through unique buyer-driven supply-chain capabilities.36 Designers and others at company headquarters monitor real-time information on customer purchases to create new designs and price points. Through standardized product information, Zara can quickly prepare computer-aided designs with clear manufacturing instructions.

In manufacturing, cut pieces are tracked with the help of bar codes as they flow further down the supply chain. The company’s distribution facility functions with minimal manual operations as optical readers sort and distribute more than sixty thousand items of clothing every hour. Zara also leverages the close proximity of production to the central distribution facility to reduce supply-chain risk and lead time.

Complete control over its value chain helps the company to design, produce, and deliver new apparel to stores in around fourteen days, where other industry players typically spend about nine months. Zara’s smaller batch sizes lead to higher short-term forecast accuracy and lower inventory cost and rate of obsolescence. This reduces markdowns and increases profit margins. For example, unsold items at Zara account for 10 percent of stock, compared with the industry average of 17 to 20 percent.

Orchestrating and Unleashing at Air France

Companies like Kimberly-Clark and Zara have created substantial benefits by digitally linking every element of their supply chains more closely. While orchestration-focused approaches like these can be very valuable, other opportunities exist in breaking the orchestrating-versus-unleashing paradox. Operations become better orchestrated while workers gain freedom to do some tasks outside the leashes of paper, desks, and office hours.

Air France found that it could break the paradox by moving from paper to electronic materials in its flight operations.37 The company’s documentation challenges extend to four thousand pilots and hundreds of flights per day around the globe. Previously, each pilot, aircraft, and flight route required a unique set of documentation on board, collectively adding sixty pounds of paper to each flight.

Additionally, paper was a poor technology base for orchestrating operations. Critical decisions about safety or scheduling waited as typists entered information from forms into systems. Truly time-critical processes required employees to coordinate manually by phone or radio, and they often had to fill out forms after the process finished.

The logistics of coordinating documentation for each flight is no small task. In the past, each plane carried reference documents and pilots kept separate copies at home. Dedicated rooms in two Paris airports—Orly and Roissy—held racks of information cards on each destination Air France served. Each aircraft required specific manuals and performance calculators, with variations depending on the plane’s specific engine system. Back-office personnel prepared a flight folder for each flight that included weather information, airport details, and flight itineraries. This mountain of paper documentation helped maintain the safety and security of Air France’s flights, but also created a lot of operational complexity. Sebastien Veigneau, first officer at Air France, explained: “In the past, we used to receive our planning every month on printed paper. Planning documents were dispatched individually to all four thousand pilots and all fifteen thousand stewards, stewardesses, and pursers.”38

In 2006, Air France managers realized that technology could unleash employees from paper forms and manual coordination, while orchestrating processes more closely. The firm could reduce cost and risk, improve pilot training, and make critical processes faster. Air France started by digitizing most reference and flight documentation and then issuing laptops to all pilots. The pilots could use laptops to do tasks they formerly did on paper. Meanwhile, by installing tablets called Electronic Flight Bags on its aircraft, the company paved the way to reducing paper in flight operations. Air France benefited because all notes were legible and available in real time and in the same place. Digital documentation was easier to maintain and update than paper-based documentation. Pilots could have the most up-to-date documents with a single tap. And passengers benefited by not having to wait so long because operations were more efficient.

Although the initial process showed promise, it also encountered difficulties. Application design issues and pilot reticence led to some dissatisfaction. In 2009, the company paired IT personnel with active pilots to develop a solution that was faster, simpler, and more modern. In just a few months, the team developed an iPad-based solution dubbed Pilot Pad that pilots found more useful than the original laptop-based approach.

Air France’s operational changes were largely invisible to customers, but the efforts affected customers through greater safety, better coordination of flight crews and airplanes, and reduced waiting time.

Digital orchestration enabled Air France to improve its processes substantially. However, the benefits extended beyond the tarmac. The transformation also unleashed pilots from tasks that had created frustration and extra effort in the past. Using their PilotPads, pilots could access the company’s online scheduling platform from anywhere in the world. Now, whenever Air France updates a document in the library, 60 percent of affected pilots review it within twenty-four hours, which allows the pilots to stay informed, wherever they are. The pilots can also do required training courses more conveniently. Previously, pilots were required to attend in-classroom presentations to keep up-to-date with the latest aircraft and practices—a challenge, given the typical pilot’s busy travel schedule. New e-learning modules enable pilots to complete training whenever and wherever they wish.

To date, the Pilot Pad program has been a success. By unleashing itself from paper, Air France his orchestrated its processes better than ever before. Plus, the tablet device has unleashed pilots to do their nonflying duties wherever and whenever they want. As Veigneau told us, “When Pilot Pad was rolled out, it turned flight operations into an efficient and user-friendly process. The only question we have from pilots now is, ‘When will I get my Pilot Pad?’” Air France expanded the program to all of its pilots in 2013. Now, seeing the solution’s potential for pilot engagement, the flight operations group plans to continue pushing its boundaries through new digital capabilities. For example, cabin crew are being equipped with iPads in 2014.

BUILDING YOUR OPERATIONAL ADVANTAGE

The digital transformation of operations began in the 1960s and 1970s with basic transactional systems. It accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s with the introduction of PCs, e-mail, and online systems. It leaped forward in the 2000s with mobile phones, ubiquitous internet, and cheap global communications. Now it is poised to accelerate even faster through technologies such as flexible robotics, advanced analytics, voice and translation technologies, and 3-D printing.

So, how can you think about opportunities to transform your operations? The digital operations advantage is about more than great tools. It’s a combination of people, processes, and technology connected in a unique way to help you outperform your competitors. None of the examples in this chapter were only about adding new technology to a process. They were actually about using digital technology as an opportunity to rethink the way your company’s processes work. If you grasp the power of transformed operations, you can create an operational advantage that few others can copy.

In looking for opportunities to transform operations, don’t think about mobile or analytics or embedded devices. Think about constraints that you’ve lived with for years—constraints you don’t even consider constraints because they’re just common knowledge. Are the assumptions behind those constraints still true? Or can new technologies allow you to work radically differently? That is where you can find the best opportunities.

Look for ways to apply each of the six levers to your operations. And figure out how you can use technology to break paradoxes. But don’t stop there. The Digital Masters we studied used multiple levers—alone and in combination—to transform their operations. One change led to another and then another.

Companies have unleashed their product design and production processes from paper, opening up possibilities to orchestrate their processes in new ways. Codelco used automation to control and then innovate its processes. Asian Paints rethought assumptions from a legacy of history, standardizing its sales processes while empowering frontline salespeople to perform more-strategic tasks. Caesars controls its processes digitally, while empowering workers to make decisions independently and actively working to find innovations that improve each process.

Digitally transforming operations requires vision that extends beyond incremental tweaks. But it also requires something more. Transformation requires good data, available in real time, to the people and machines that need it. For many companies, true operations transformation starts by overhauling legacy systems and information to provide a unified view of processes and data. This is no small task, but it is well worth the effort. As we discuss in chapter 8, improving your technology platform is the foundation upon which all other elements are built.