2 Civil society and political parties in the Czech Republic

I am for the decentralisation of power& . I am for the progressive creation of the space for a diversified civil society in which the central government will perform only those functions which nobody else can perform, or which nobody else can perform better& . The creation of a genuine civil society of the western type will take a very long time, but that does not mean that we should not be creating favourable conditions for its emergence. It is not a question only of regional autonomy or of the creation of a non-profit making sector or of the system of tax allowances. It is a question of much more, of the method of thinking which enables citizens to trust.

(Václav Havel, Právo 18 November 1995)

Our country is following a thorny path from communism to a free society and market economy so far without any real wavering& . On that path we have already passed several crossroads& . The first was the clash over economic reform, over whether we want genuine capitalism or whether we would try for a third way, socialism with a human face, perestroika& . The second was the clash over the character of the political system itself, over whether we want the standard parliamentary pluralism based on the key role of political parties or whether an allembracing non-politics should dominate. The third was the clash over maintaining the homogeneous common Czechoslovakia or over its division, if that proved impossible. The fourth concerns the very conception of the content of our society & whether we want a standard system of relations between the citizen (and community) and state, supplemented with voluntary organisations, or whether we will create a new form of collectivism, called civil society or communitarianism, where a network of ‘humanising’, ‘altruising’, moralsenhancing, more or less compulsory (and therefore by no means exclusively voluntary!) institutions, called regional self-government, professional self-government, public institutions, non-profit making organisations & councils, committees and commissions & are inserted between the citizen and the state.

(Václav Klaus, Lidové noviny 11 July 1994)

Introduction

These quotations illustrate the sharp conflict over the meaning and importance of ‘civil society’ in the Czech Republic in the mid-1990s. They also helpfully illustrate the modes of thought and argument of ‘the two Václavs’. Havel, the former dissident who became President of Czechoslovakia in 1989 and then of the Czech Republic, saw himself maintaining a position derived ultimately from fundamental moral principles. Klaus, the disciple of the monetarist economist Milton Friedman, was federal Minister of Finance from 1989 to 1992 and then Czech Prime Minister until November 1997. He saw himself opposing and defeating successive attempts to deviate from what he believed to be clear messages from ‘standard’ western theory and practice.

This chapter aims to set that conflict over civil society in the context of an emerging political system. It is built around two questions. The first concerns why there should have been such sharp disputes over a vague, ambiguous and rather abstract term. To some extent the terminology and the form taken by the debate could have reflected the very different predilections and past interests of the key protagonists. Behind it, however, lay deep disagreements, albeit ones that were not always very directly formulated, over the kind of political system they wanted to see and over the relationship between the political system and society in general.

The second question concerns how far the debate influenced the development of the political system and forms of interest representation. It coincided with, and was in part a reaction to, attempts by Klaus' Civic Democratic Party to minimise the influence of other political or social forces. Havel became a part of a diffuse opposing trend that resisted the exclusive domination of politics by parties and pointed towards a more complex institutional framework for the control, and possibly also decentralisation, of power.

What is civil society?

The term ‘civil society’ has been used over a very long period of time, with roots back at least to Aristotle. It is therefore hardly surprising that its meaning has shifted over time, leading even to the despairing suggestion that ‘there is no discovering what the term means’ (Nielsen 1995: 41). Ambiguities in its meaning did colour the debate, but both main positions actually have clear theoretical and historical antecedents.

The important break in the development of the term was the notion of a separation, or even counterposition, between state and civil society. John Keane (1988b: 35–71) sees the beginnings with the Scottish eighteenth-century philosopher Adam Ferguson who argued that the danger of ‘despotical government’ was opposed by the ‘sense of personal rights’ (Ferguson 1966: 273), strengthened by forms of involvement in public activity. However, Ferguson's use of the term ‘civil society’ did not imply the advocacy of associations fully independent of the state: that distinction was to come later.

Hegel, although he used the term civil society, gave it a meaning that has little relevance to the Czech debate. He did see a private sphere, but it was a chaotic arena, full of conflict, which needed to be given order by a political authority, the state. More relevant was almost the exact opposite view derivable from Adam Smith's ‘invisible hand’ of market relations (cf. Cox 1999: 454). Civil society is then the sphere of private, individual activity, free from state control, but it is largely able to organise itself as long as a state maintains set rules. It could even be equated with private property. Klaus seemed happy with such a notion, viewing ‘liberal civil society’ as part of the heritage of his favoured ‘conservative right’ (Klaus 1992: 42).

The notion of a distinct civil society as a barrier against ‘state despotism’ was developed by Alexis de Tocqueville in his study of American democracy in 1831. To him the contrast was clear with a France where he saw negative consequences of uncontrolled power in different periods from an established, and then from a revolutionary, order. In America he saw power controlled by a popular willingness to become actively involved, with public discussion of even ‘the most trifling habits of life’ (Tocqueville 1980: 79). This led in turn to a plethora of free associations, independent of the state. They could have common economic concerns, but were also ‘religious, moral, serious, futile, extensive or restricted, enormous or diminutive’ (ibid.: 111). The level of involvement led him to suggest that debates at the top level were ‘a sort of continuation of that universal movement which originates in the lowest classes of the people’ (ibid.: 79).

Havel was close to this starting point, but it appears limited in a more modern world of mass parties, organised interest representation and diverse centres of power. Control of state despotism can no longer be the sole area of concern. Thus trade unions emerged largely to counter the power of private property, but are also involved in conflicts with the state and play a variety of roles in political life. Business too can organise, coordinating its position against organised labour and ensuring independence from the state, but also influencing the latter's behaviour. The counter-position of state to civil society is too simple a starting point for analysing such processes.

Nevertheless, the term civil society underwent something of a revival in the late twentieth century with a new meaning as an informal and spontaneous sphere. The problem of defining the relationship between civil society, parties and interest representation is resolved by defining civil society as everything apart from the state, economic power, market relations, parties and clearly formal forms of political activity (Cohen and Arato 1992). This definition acquired life with the growth of ‘new’ social movements outside previously established political structures (cf. Keane 1988b). Parties, trade unions and the like had become established. To some they were another element restricting the representation of the full diversity of opinions and interests. A definition based on ‘informality’ implies a dividing line between political and civil society that is vague, moving as a regime changes or as a movement gains ‘established’ status. Nevertheless, this was a notion that could find a strong resonance in east-central Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. It even still had some influence in the specific situation in Czech politics after 1998.

However, even the vision of democracy derived from de Tocqueville is not shared by all intellectual traditions. Klaus, familiar largely with what he saw as ‘standard’ economic theory, was a confident advocate of the radically different perspective articulated by the economist Joseph Schumpeter (1943). The starting point was rejection of direct popular decision making. The best realistic alternative Schumpeter saw was a system allowing choice between individuals. There was a conscious analogy to the competition between firms in economic theory. The crucial point, however, was that democracy not only centred on, but also meant no more than, a system of periodic choice between professional politicians. The voters must not indulge in ‘political backseat driving’. They ‘must understand that, once they have elected an individual, political action is his business and not theirs’ (Schumpeter 1943: 295). There was thus no place for associations or interest representation. This was a licence for an elected dictatorship.

Both neo-classical and neo-liberal economics take this further, seeing interest representation as positively harmful, as distorting the otherwise ideal market outcomes. Trade unions behave as economic monopolies, raising remuneration for some only by ‘depriving other workers of opportunities’ (Hayek 1984: 52). State provision breeds a ‘bureaucracy’ that is self-serving and inefficient (Niskanen 1971 and Niskanen 1994), quite unlike that portrayed in Weber's ‘naive sociological scribblings’ (C. Rowley, in Niskanen 1994: vii). Even elected government may be dangerous, enabling a majority to impose policies to its advantage on society as a whole (Tullock 1976). The solution is the free market wherever possible.

Hayek (1944), and in a more popularised version Friedman (1962), portray the free market and private property as a necessary, and it seems also sufficient, condition for political democracy. Private wealth is the barrier against political dictatorship and any interference in the market is itself an infringement of freedom. It even carries the ultimate threat that it might culminate in an elected government whereby ‘a majority imposes taxes for its own benefit on an unwilling minority’ (Friedman 1962: 194). In this view, any form of ‘socialism’, even if from an elected government, threatens both personal freedom and economic prosperity.

Equating political freedom to property ownership is difficult to reconcile with the historical evidence on the crucial role of workers’ movements in the development of political democracy (Rueschemeyer et al. 1992). Indeed, in Czech history too the political forces representing rural and urban business were either suspicious of universal suffrage or opposed to it, and on grounds very similar to those behind Friedman's reservations about democracy. The Social Democrats were left to lead demonstrations, culminating in a general strike in 1905, to force concessions out of the Habsburg empire.

Friedman's followers need not reject de Tocqueville's notion of civil society built around voluntary association, but in Friedman's world they rely on support from ‘a few wealthy individuals’ (Friedman 1962: 17). They therefore depend on the prior existence of capitalism and inequalities in wealth. Friedman also advocates ‘private charity directed at helping the less fortunate’ (ibid.: 195) as the best solution to problems of poverty and deprivation. In this case voluntary associations could play a role, filling in those few cases where markets, for reasons not made clear, may produce results not judged ideal. There is, however, no legitimate place for the collective representation of interests that might temper the power associated with wealth or alter the outcome of free market processes.

While these ideas of Friedman and Hayek were gaining influence among a small circle of professional economists in the 1980s, active dissidents were more attracted to the notion of civil society as a counter to formal political authority. This had a special resonance in Czechoslovakia, where it echoed a nineteenth-century tradition. Masaryk (1927: 47) claimed to have set the aim to ‘de-Austrianise our people thoroughly while they are still in Austria’. A ‘non-political politics’ would enable the Czech nation to develop within the substantial space allowed for cultural and economic advancement, while not challenging the key areas of ‘big’ politics, such as foreign and military policy (Havelka 1998: 460–1).

The ‘non-political politics’ of the 1970s and 1980s fitted the specific situation of a repressive regime confronting a weakly organised and seemingly powerless opposition that was isolated from any sources of social discontent. The dilemma, of ‘what to do when we can't do anything’ (Otáhal 1998: 467) was resolved by involvement in small-scale activities, such as seminars and samizdat publications. Challenging the power structure directly was not a serious option.

Havel gave this a theoretical justification around his notion of ‘anti-political politics’. He was not interested in power, but rather in an individual moral revival amounting to ‘living in truth’. There was no political strategy, far less so than in the case of much of the Polish opposition or even Masaryk in the 1890s, and no clear vision for a political or economic system in the future. The agenda was left at a very general level, at the ‘prepolitical’ stage (Havelka 1998; Otáhal 1998; Havel 1988). This did not prevent Havel from emerging to play a leading role in the mass movement that established Civic Forum – he chose the civic part of the name – and ended communist power. It did, however, mean that he had only the vaguest of theoretical armouries relevant to the new situation after November 1989.

Civil society and the 1989 revolution

Despite the breadth and spontaneity of the initiatives leading to the emergence of Civic Forum (OF), its rise cannot be interpreted as a victory for civil society over a repressive regime. Throughout the early months of 1990 OF was primarily the vehicle of political revolution, forcing changes in personnel in the administrative machine, in economic life and in local government. It was moving into the arena of power. The spontaneous aspect continued in the absence of formal organisational structures as it brought together opposition groups spanning the political spectrum. The effect was to leave the body of activists at local levels divorced from central decision making. Indeed, major policy issues were increasingly taken within government structures without wider consultation. Civil society as normally understood therefore had to develop as something distinct from Civic Forum.

The overthrow of dictatorships in Latin America and southern Europe was frequently followed by an ‘explosion’ of civil society with a ‘multitude of popular forms’ (O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986: 53). In purely numerical terms the same could be said to apply in the Czech Republic where civil society has been conveniently defined as registered non-state non-profit making organisations (e.g. Zpráva 1999: 19): these numbered 2,500 by the end of 1990 and 79,000 by December 1999. This, however, gives only a partial picture, particularly where the political influence of the various organisations is concerned. The change that took place was as much a transformation of existing structures as a creation of new ones from scratch.

Repression in Czechoslovakia had not prevented society from organising. The point was rather that organisations were controlled and incorporated. Many completely new organisations did emerge to represent interests, opinions and activities, but they were generally small in relation to the transformed versions of ones that already existed. Some have consciously aimed to influence policy, but they typically do this by personal links to MPs, ministers or officials in the new power structure. They generally steer well clear of more public forms of protest (cf. Frič 2000).

The only organisations with the will and potential to influence political events by mass protests have been the trade unions and the representatives of cooperative farmers. Their links to the new power structure were initially weak and they encountered initial suspicion over their past ties to the old regime. The guiding spirit in trade unions therefore became decentralisation and depoliticisation with a rapid devolution of power into local organisations rather than a desire to play a central role in a new political structure (Myant and Smith 1999). As they redefined their role in society they sought a formal tripartite structure that would recognise their right to a voice on a clearly defined range of issues relating to employment and social policies.

Civic Forum itself, it can be added, started with a modest view of its own role. The initial assumption had been that it would quickly disappear, giving way to newly emerging political parties that would contest elections. Such a process had been eased in eastern Germany by importing a party system from the West. Effective new parties did not emerge so quickly in Czechoslovakia and it was soon accepted that OF would itself contest the first parliamentary elections, scheduled for June 1990.

In this early period Civic Forum's development was dominated by two potentially conflicting trends. One emphasised the creation of a new political system with all the checks and balances associated with a mature democracy, while the other emphasised a firmer line against the remnants of the old regime, merging in extreme cases into a crude anti-communism. The clearest advocate of putting primacy on ‘creating’ was Czech Prime Minister Petr Pithart. He was already worrying at a OF assembly on 21 January 1990 that the people could come to fear the new authorities as much as they had feared the communists in the past. His call was to finish ‘as soon as possible with the dismantling of the old’ and ‘to build a state, an independent civil society, a prosperous economy, in short a civilised European society’ (inFórum 23 January 1990).

This thinking was a powerful influence on policy making. It even contributed to the development of formal structures for interest representation with Pithart playing an important role in the creation of a tripartite structure that assured trade unions and employers’ organisations access to the government on issues that concerned them directly (Myant et al. 2000). However, the general principle of the need to open up political life and to control those in power could not lead to any inspiring political slogans. Modern democracies, as is often argued, themselves developed gradually as the result of pressures from, and compromises between, conflicting forces. It could not be an easy task to win enthusiasm for the need to control one's own power when leading revolutionary changes. Indeed, Pithart was frequently accused of scoring ‘own goals’ that reduced his political standing by appearing to be ‘soft’ on communists.

The alternative, ‘anti-communist’ trend had an automatically easier appeal, seeming to follow more naturally from the revolutionary changes. It was fuelled by reports that the Communist Party (CP), or CP members, were resisting changes. In reality, although its members grumbled and clung to positions where they could, the party itself could mount no serious organised opposition to the loss of its positions of power. However, it continued to exist, kept the word ‘communist’ in its title, sought to cling on to as much as possible of its substantial wealth – equivalent to 1.6 per cent of GDP and 283 times the property held by OF (Svobodné slovo 25 October 1990) – and occasional early reports showed that many of its members still occupied leading positions. These, rather than social interests or the creation of democratic structures, were issues that could mobilise public demonstrations throughout early 1990. A significant, and very vocal, part of public opinion favoured banning the CP in total – 37 per cent of the population supported this in an early opinion poll (Rudé právo 17 May 1990) – and there were more widespread calls for a thorough purge of positions of authority.

The 1990 election gave OF approximately half the Czech vote. It had a comfortable majority in the Czech and, together with its Slovak counterpart Public Against Violence, federal parliaments. Its detailed programme naturally emphasised the ‘constructive’ trend, but its appeal was based around general themes rather than specific policies. It presented itself as the key force in ending communist power and as the best guarantee against a return to the past. It promised to continue with the creation of a democratic system, a market economy and with ensuring a successful ‘return to Europe’. Its own status and role within these processes were left vague. Indeed, a key appeal had been its slogan of ‘parties are for party members, Civic Forum is for everyone’, a wording that fitted with the spirit of the time, but not with plans that might include acceptance of its future transformation into a political party.

Ultimately, contesting elections imposes a certain logic on an organisation's development, requiring a degree of discipline, an organisational structure, a means of funding and a body of activists. It also logically means hampering rather than encouraging the development of other parties. Moreover, having won the parliamentary elections, OF again took responsibility for government. Splitting into the diverse trends that had come under its umbrella could threaten the stability of that government. Havel and others began to reason that OF would have to continue at least to contest the next parliamentary elections in 1992.

This realisation of permanence coincided with pressure from a number of Civic Forum assemblies for a thorough purge of public and economic life. Society, in Havel's words, was ‘nervous and impatient’, as reflected in ‘hundreds of letters daily’ demanding more dramatic changes (inFórum 18 September 1990). This found acceptance around the aim of destroying the ‘nomenclature brotherhood’ that was alleged, albeit with little definite evidence, to be ‘strengthening its positions’ (I. Fišera, inFórum 21 August 1990).

A reasoned, if uninspiring, alternative to this mood came again from Pithart. Existing laws did not allow for a sweeping purge with arbitrary dismissals, although some changes to the law were to create more scope for removing job security from high officials. His objective of creating a modern political system meant that OF ‘must be tolerant and farsighted enough to aid the emergence of parties alongside us’ (inFórum 18 September 1990).

Enter Václav Klaus

A new way forward came from a somewhat different direction. Once it was decided that Civic Forum needed a stronger profile around a new chair, Václav Klaus, at the time federal Finance Minister, emerged with enthusiastic support as ‘the author of the economic reform’ (inFórum 17 October 1990). He was elected chair by 115 votes to 52 for Havel's favourite Martin Palouš at the OF assembly on 13 October.

The background had been his role in developing ideas on reform within his ministry from early 1990 onwards. He had focused on essentially the standard IMF stabilisation package plus voucher privatisation, while making some concessions to advocates of a more interventionist approach. Despite criticism from specialist opinion in the following months, parliament approved the programme in September and Klaus was keen to present himself as its main author and defender (Myant 1993). Klaus's thinking dominated the formulation of the OF programme at assemblies in December 1990 and January 1991. His position can be characterised around three elements. The first was an insistence that Civic Forum should become a party, not ‘an all-embracing political movement’, with a clear programme based around economic reform and the proven models of democracy from the Czechoslovak past, western Europe and North America. This, it was argued, required support from a disciplined movement. Subsequent events suggested no need for a disciplined mass membership, but Klaus was worried that the effects of economic reform would provoke social discontent. Discipline among ministers and MPs could then prove important.

The second element was a clear commitment to a rightwing perspective that required firm rejection of socialism, social democracy and anyone who wanted ‘to speak of a market economy with various kinds of adjectives’ (inFórum 17 January 1991). Klaus had already won implicit acceptance for his rejection of the ‘social market economy’, the successful slogan of Germany's Christian Democrats. Elements of the reform scenario agreed by parliament (‘Scénár ekonomické reformy’ Hospodárské noviny 4 September 1990), with references to industrial, energy and transport policies and a substantial programme of state initiatives to create a comprehensive environmental policy, had quietly disappeared. Instead came the Friedmanite insistence that private ownership was the key to solving all economic, social, environmental and political problems.

Thus political reform, meaning the construction of an institutional framework for democracy and civil society, was subordinated to economic reform. References did remain to the need to find mechanisms to control the state apparatus and to develop strong local government, but private property was creeping forward as the only precondition worth mentioning for defending individual rights (inFórum 17 January 1991).

The third element was his approach to anti-communist rhetoric. Klaus was from the start against any further ‘purges’. He later claimed to have been guided by a clear position of favouring ‘a systemic solution, overcoming communism as a system, and not an individual, personal confrontation with the individuals responsible for the evil and injustice of the communist regime’ (Rudé právo 13 August 1994). He even suggested on occasion that the best way to deal with former communists was to help them become capitalists. His opposition to the ‘individual’ approach brought him into potential conflict with a strong and persistent body of opinion, and one the support of which he needed to ensure dominance within OF. He was not enthusiastic about the ‘lustration’ law, passed in October 1991, which barred for five years various former communist officials and secret police informers from holding state office, but he made little public show of his doubts. It was easy enough to keep any of his allies directly affected in post by transferring activities into the private sector where no bars applied. In general, he made what concessions were necessary to ensure an implicit alliance with ‘anti-communist fundamentalists’. They in turn were impressed enough by his brand of rhetoric. As various of his views recorded in this contribution indicate, he subjected those with ideas to the left of his own to scathing criticism, effectively accusing them of threatening a return to the communist past. Anti-communism to him was not a matter of individuals’ pasts, an issue that caused him very little concern, but a weapon against political opponents of the present. It sounded quite good enough to give him the status of the dominant personality on the political right.

The direction Klaus was giving Civic Forum in the latter part of 1990 led to the departure of some MPs into an emerging Social Democrat group and ultimately to a division of the organisation into two streams. The alternative position favoured a looser internal structure, perhaps hankering to maintain something of the heritage from the period since November 1989, with a greater concern for social issues, albeit alongside commitment to a market economy. For the sake of government continuity, the two groups held together in a loose federation until the 1992 elections. On 21 April 1991 Klaus was elected chair of the new Civic Democratic Party (ODS), while a majority of former dissidents and government ministers went into the looser Civic Movement.

Klaus's conception had no place for political or social organisation beyond his own clearly rightwing party which was to promote private property as the foundation and guarantor of individual liberty. Nevertheless, there was some scope for pressing social interests. Organisations associated with the past continued to be cautious, but some new, and often very small, groups could make an impact when they had the right personal connections and when issues were repackaged in terms of reconciliation with the communist past. Individual MPs, themselves not tied to anything approaching party discipline, would willingly take up such demands, and frequently embarrassed the government. Thus the voice of emerging small businesses became audible around demands for return of property confiscated in the past. Klaus saw this as a diversion from rapid and comprehensive privatisation, but he conceded quickly enough for his position to receive little publicity.

The voice of farmers, a group that was hit hard and very early by economic changes, was at first most audible when it came from newly emerging organisations that wanted scope for returning land taken by cooperatives into private, individual use (Fórum no. 15, 1990: 11). The Civic Forum draft programme presented on 8 December 1990 started its agricultural policy section with a call to ‘redress the crimes perpetrated by the totalitarian regime’ (inFórum 13 December 1990, supplement), a position that dominated policy making towards agriculture throughout 1991. The biggest organisations representing the agricultural community were more concerned with addressing the difficulties created by economic reform and defending existing cooperatives against what they saw as a bigoted and politically motivated attack led by people ignorant of farming. Their voices were eventually heard in government after powerful public demonstrations (Myant 2000), a tactic that newer groups neither needed nor wanted to use.

Czech parties and the ODS

The weakness of organised interest representation across east-central Europe was a common feature in the early 1990s. The Hungarian political scientist Attila Ágh has referred to a ‘partyist’ democracy, with visible politics dominated by clashes between party oligarchies (Ágh 1998: 12). Czech parties, however, were themselves weak in measurable indicators, such as membership and committed support (cf. Jičínský 1995). They appeared to be ‘cadre parties in the truest sense of the term’ (Šamalík 1995: 257), brought together around the vaguest of programmes, and possibly charismatic leaders, and lacking internal cohesion or discipline. Indeed, more than seventy out of the 200 Czech MPs had changed party before the 1996 elections, albeit with changes overwhelmingly among opposition parties (A. Vébr, Rudé právo 13 May 1995, and Brokl et al 1998: 25).

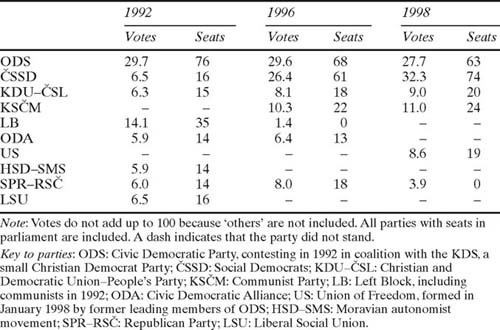

Nevertheless, generalisations need to be tempered by a recognition of diversity in party types across the Czech political spectrum. Table 2.1 shows the parliamentary election results that secured the ODS a dominant position in coalitions in 1992 and 1996. Its coalition partners were the People's Party-Christian and Democratic Union (KDU–CSL) and the Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA). The former inherited property and a party machine from an existence as a loyal satellite party before 1989 and soon claimed to have doubled its membership to a very satisfactory 40,000. It sought to profit from association with powerful Christian Democrat parties in western Europe, adopting the slogan of a ‘social market economy’. The ODA remained a select group with about 2,000 members, created in 1989 by long-standing dissidents and neo-liberal economists.

The opposition included the farright Republicans and various centre groupings that often seemed to be searching for issues to take up. One, for example, latched onto a campaign for restoration of the death penalty. There seemed to be little ‘middle ground’ when the key issues were reconciliation with the communist past and economic reform.

The left was dominated by two parties. The CP was completely out of touch with the spirit of the time, but retained an ageing core of members, falling from 1.7 million in 1989 to 355,000 in 1992 and 121,000 in 2001 (Fiala et al. 1999:180–2 and http://www.kscm.cz). It retained a substantial

apparatus, but made few new recruits (under 5,000 in the period up to 2001) and 65 per cent of all members by 2000 were over 60. They were clinging to the past with little serious ambition to take part in power again and had little in common with the notion of cadre party. The Social Democrats (CSSD) benefited both financially and politically from links with friendly western European parties, but suffered from a slow start before leading figures drifted across from OF. Membership was never high, reaching about 13,000 in 1996, and there were no formal links to organised interest representation. Trade unions preferred to keep a distance from all parties. The CSSD's popularity increased as the leadership moved to condemn the corruption and rising inequality that they associated with privatisation. It probably benefited from a growing awareness of social issues and from a move towards more active campaigning by trade unions from 1994 onwards.

The ODS too was small and fits to some extent with the characterisation as a ‘cadre’ party. It won support by appearing as the most committed advocate and architect of the new political and economic order. However, it was closely tied in with the new structures of political and economic power, leading to a characterisation as a ‘nomenclature’ party ‘of a special type’ with members in leading positions in the state administration and privatised enterprises (Z. Jicínský, Rudé právo 24 January 1994). Its nature can be demonstrated around the three key areas of membership, funding and internal differences.

Klaus's original claim had been that 10 per cent of Civic Forum supporters would be willing to join the ODS, leading to a mass ‘conservative’ party. This proved unrealistic, but also unnecessary and for him possibly even undesirable. The ODS to Klaus was a vehicle for supporting his government's position of power so that it could implement his conception of economic reform, based on privatisation and the emergence of prominent Czech entrepreneurs heading powerful business empires. He had no interest in a political structure giving scope for interest representation, debate and freely competing views. It was even suggested that he would have been happy had the party dissolved itself after the 1992 elections to reemerge only for the next elections in 1996 (B. Pecinka, Lidové noviny 9 September 1994). In practice ODS membership was steady at around 23,000.

Parties typically need members to provide revenue, to fill elected posts in local government and to mobilise around certain objectives. Revenue came by means indicated below. The party was too small to contest more than 26 per cent of Czech parishes in local elections in 1994 – only the communists could contest in more than half – and, of the 20,000 representing the party, only half were members (Hospodárské noviny 6 October 1994). Not surprisingly, local organisations remained weak. The party vice-chair in charge of organisation complained at the congress in December 1996 that only a few activists were involved, and then only in ‘formal, organisational tasks’ (L. Novák, http://www.ods.cz). This, however, is only part of the picture. Although there was little sign of activity in the sense of an interest in political debate, and certainly not in challenging the leadership, a decentralised and loose organisational structure created the ideal environment for a party that could serve as a mechanism for ambitious individuals to achieve positions of personal power.

Funding was linked to the party's ability to help with privatisation decisions. Heads of nationalised industries, hoping for decisions favourable to themselves, openly sponsored the party in 1994. This practice was stopped following opposition from all other parties. It appears to have been replaced by less public methods. A forensic audit of the party's accounts published by Deloitte and Touche in May 1998 revealed evidence of systematic errors, omissions and contraventions of the law. One case that probably related to a major privatisation decision came to court around charges of tax evasion (proving corruption behind a donation would have been a practical impossibility) against an ODS official. The twenty-five witnesses called in June 2000 remembered or knew nothing of the details of how the party had been funded. The party's accounts, showed Kcs 43.5 million from sponsorship in 1996. This is considerably less than the Kcs 161.5 million subsequently received from the government as funding linked to election results, but the sponsorship figure need not be a reliable guide in view of the possibility of secret donations or of firms themselves paying ODS election expenses directly. As one insider suggested at the time, the 1996 campaign was financed partly ‘from black, untaxed funds’ (T. Dvorák, Právo 2 September 1996). These, it should be emphasised, were little more than business transactions that related specifically to privatisation and implied no further implications for ODS policy. This was not a case of an organised interest influencing a party's policy. Klaus was happy to dismiss collective representation from business and also had little time for individual managers who were critical of government policies. His government was to remain impervious to outside pressures.

Within the party too, as already indicated, there was very little political discussion. Conflicts and differences did emerge, but they were largely to do with personal ambitions and accusations of corruption against leading local individuals. Behind the scenes, however, three political positions played a role in the party's development. The first was Klaus's focus on economic reform. The second was that of ‘fundamentalist anti-communists’. The third was associated with Josef Zieleniec, Czech Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1993 to 1997. He was ‘even said to be the one man from whom Klaus is capable of taking even very sharp criticism’ (B. Pecinka, Lidové noviny 9 September 1994) and is sometimes credited with authorship of the idea of creating a mass, right-wing party (e.g. Husák 1997: 84). Klaus's great ability was to react quickly and improvise to keep a balance between the first two of these without it being too obvious when he had to make compromises and concessions.

Naturally, Klaus denied that he had propagated a personality cult and others whose voices could be heard feigned offence at the suggestion that it was a one-man party. However, only Miroslav Macek, one of the party's deputy chairs and a man whose self-confidence and thirst for publicity almost rivalled that of Klaus, publicly claimed to have ‘convincing written evidence that Václav Klaus has accepted a number of my suggestions’ (Právo 20 November 1999).

The ‘fundamentalist anti-communist’ position was visible not in an alternative personality, but in a small number who did not vote for Klaus as party chair, amounting to 16 per cent of delegates at the November 1993 congress. There was occasional talk of a breakaway party, but the most serious ‘fundamentalist’ party rarely passed the 5 per cent barrier in opinion polls. Klaus was willing to compromise, for example accepting an extension of the validity of the lustration law to 2000. He was more reluctant to concede when anti-communism threatened the creation of large Czechowned business empires, but he had on occasion to yield when publicity was given, probably thanks to colleagues within his own party, to the communist past of some of his favoured prospective captains of Czech industry.

The issues raised by Zieleniec were even more central to the nature of the ODS, but he lacked the political charisma and support base to press them with any serious chance of success. He began with cautious suggestions in 1994 that the party might benefit from greater programmatic clarity. This could be seen as an alternative, and even a threat, to Klaus's method of holding together the diverse personal interests within the party by a combination of charisma and improvisation (P. Pfíhoda, Lidové noviny 15 September 1994; P. Šafr, Lidové noviny 28 September 1994). Zieleniec tried again after the disappointing 1996 election results, suggesting that the ODS would never reach his target of 40 per cent of the votes if it continued to be a party that ‘always speaks with one voice’. He suggested that policy should come not just from above but ‘from plurality and political battles on all levels’ and saw the key in welcoming fractions and an internal life which encouraged debate (Mladá fronta Dnes 5 August 1996). There were a few mutterings of support and some voices taking the point towards its logical conclusion, asking ‘why have we left the term “social market economy” to [People's Party leader] Lux?’ (R. Dengler, Právo 6 August 1996). Klaus returned early from his holiday, described Zieleniec's contribution as ‘important’ and ensured that it was quickly buried.

Zieleniec tried yet again in 1997, advocating a shift in the ‘method’ of funding away from the efforts of top officials directed towards big sponsors. Instead, the party would rely more on smaller donations. As he pointed out, that would imply a shift in policy orientation. It would mean listening to ‘small’ as well as ‘big’ voices (Mladá fronta Dnes 30 October 1997). He was working towards a coherent alternative of a party that tries to forge links with, and to take up the interests of, diverse social groups that might be expected to gravitate towards the right. It is an approach familiar in western Europe. The trouble for Zieleniec was that the party had developed in a very different way. He could refer to the desirability of debates and fractions, but there was no basis for any to emerge. He was proposing an abstract idea with no resonance in a membership that had no reason to challenge its leader.

Zieleniec resigned from the government on 24 October 1997 and revelations about the party's secret funding shortly afterwards forced Klaus's resignation. The ODS, however, weathered the storm of divisions in its top leadership and continued as the dominant force on the political right. Recorded sponsorship was down to Kcs 23.5 million by 2000, against total party income of Kcs 96.3 million. The party was even more clearly dominated by Klaus, with his picture and speeches hogging its web pages. He had, however, lost an important stage in the battle described in the next section over the nature of the political system and the relationship between parties and society.

The two Václavs

The most visible public clash over the nature of the emerging power structure was the debate between Havel and Klaus which took off after the former's New Year address for 1994 and was amplified in a series of speeches over the following two years. Havel's concerns over the government's activities were expressed in terms of the need to lay the foundations of a civil society. At first he built this around the need to respect his general moral principles of ‘tolerance’ and ‘respect for one another’. The conflict took shape as he took up practical issues, particularly noting delays over fulfilling constitutional requirements for the creation of a senate and regional authorities. By 1995 Klaus was reported saying of one of his speeches that ‘every sentence is directed against the ODS’ (Rudé právo 15 March 1995).

To Havel the basic pillar of political life should be respect for human rights, including measures against racism, anti-semitism and the abuse of power by state officials. The state itself should be run by a trusted civil service, with a role protected and defined by law. Lustration was to him an acceptable element of control over power only during the emergency period before a new state machine could be stabilised. He used his power of veto in October 1995 against prolongation of its validity to 2000, a move that was then duly overturned by parliament. Political parties had a role in politics, but not as ‘the monopoly owners of all political activity’ and they should never place themselves ‘above the state’ (Právo 13 March 1996; Hospodárské noviny 15 March 1995). Instead, he favoured decentralisation by strengthening regional government, professional associations and nonprofit making organisations. He had less to say on social or economic issues, but gradually added his concerns over economic corruption, ultimately joining in accusations of ‘mafia-like capitalism’ (e.g. Právo 2 January 1996 and 29 March 2000).

Havel's position was criticised from a number of different angles. Many commentators disliked his moralising tone, but it was precisely when he moved beyond this that real controversy erupted. Some on the left felt it should all have been said much sooner. He could, for example, have taken a stronger stand against lustration from the start, joining others who believed that it conflicted with internationally recognised standards of human rights with its presumption of guilt and retrospective applicability. Instead, he had capitulated to the craving for ‘a hysterical settling of scores with the communist past’ (J. Šabata, Rudé právo 19 September 1994). By 1995, however, there was little doubt where Havel was placing himself. ODS MPs saw his stand as an attack on their party or even as an attempt to construct an alternative government programme. It was by no means only Klaus who thought that once elected the ODS should be freed from any outside controls. In the lead-up to the 1996 election Minister of the Interior Jan Ruml, generally closer to the ‘anti-communist’ trend in the party, described the idea of an ombudsman, supported by Havel and taken up vigorously by the Social Democrats, as ‘a refined attempt to revise the results of the elections and to dominate our political scene’. He saw implementation of the constitutional requirements for a senate and regional authorities as aimed at ‘limiting the influence of the ODS’ (Právo 4 April 1996).

Klaus, however, was the most persistent and articulate in attacking Havel, as illustrated in the quotation at the start of this chapter. He tried to give his criticisms academic weight, claiming that the notion of civil society ‘stands outside current standard sociological or political disciplines’. Its basic origins, he claimed, are in ‘rationalist philosophers’ meaning, apparently, that it amounts to another attempt at ‘social engineering’ (Lidové noviny 7 March 1994). Thus, as with everything else he opposed, he tried to tar it with the socialist, or communist, brush. He felt confident enough to counterpose ‘a society of free individuals’ to ‘socalled civil society’. Oddly, his academic source, one that would have been unknown to practically all his Czech readers, referred to the notion of civil society as ‘critical to the history of western political thought’ (Seligman 1992: 5). Klaus could not convince those with knowledge of the history of ideas (e.g. P. Pithart, Lidové noviny 25 March 1994), but the key question was whether support for Havel could take an effective political form.

Broad support for Havel's conception can be followed around three themes: conflicts within the coalition, conflicts over the decentralisation of power and the issue of organised interest representation. The first of these became important both in response to Havel's interventions and as parties began thinking of the forthcoming 1996 parliamentary elections.

The ODA, with its roots partially in the dissident movement, included a role for ‘citizens’ initiatives’ in environmental protection and cultural development in its 1996 programme. It was more persistent in its support for strong regional government, including the issue in its 1992 election programme. Support for civil society, albeit in a weak form that paid little attention to interest representation, was presented as a distinguishing feature from the ODS. However, it was unlikely to be enthusiastic about a genuine opening up of power to outside scrutiny as, like the ODS, it was heavily dependent on sponsorship from business. ODA members headed the Ministries of Trade and Industry and Privatisation. It was even more of a ‘cadre’ party than the ODS and declared sponsorship income in 1996 of Kcs 8 million, the highest figure in relation to membership of any party. It was destroyed as an electoral force in early 1998 following revelations of anonymous donations.

The KDU–CSL gave general support to Havel with party leader and deputy Prime Minister Josef Lux calling for the speedy creation of a senate and regional authorities. He saw a reluctance to complete the construction of the institutional structure set out in the constitution ‘primarily in those elements that lead to a division of authority and power’. In place of the visible ‘efforts at etatisation’, he advocated ‘sharing out powers and building a many-layered, civil society’ (Rudé právo 18 July 1995). This was to prove of greater practical significance than the ODA's position. The Christian Democrats, embracing the general idea of a ‘social market economy’, were less dependent on business sponsorship and more willing to listen to organised interests both from agriculture, for which Lux had ministerial responsibility, and from trade unions.

On specific policy issues Klaus was guided by Friedman's theoretical perspective, dressed up with a portrayal of any deviation from the free market as threatening a return to the communist past. The practical implication was that there was no need to listen to voices from outside or to decentralise power in any way. It was a message he liked to press vigorously, perhaps not least in the hope of asserting discipline among his own MPs. For him there was no place for an environmental policy, and no need to listen to an environmental movement. An environmental policy proposed by a minister from the KDS, a small Christian Democrat group allied to the ODS, was voted down by ten to nine in a government meeting in August 1994, with Klaus giving assurances that the market and private property are ‘far more important than activities of the government’ (Hospodárské noviny 23 August 1994). This view could be backed up by the theoretical contribution of Nobel Prize winner Ronald Coase (1960), but that is tempered by important caveats. To Klaus, however, anything more than the market ‘would return us to the social system that we had before’ (Lidové noviny 29 August 1994).

Self-regulation of professions was dismissed just as lightly. The main practical issue was the medical profession which had a different conception from the government on the development of the health service. Klaus agreed that he might talk to them, but never wavered from his interpretation that the professional body was just ‘an ordinary pressure group’ the primary aim of which was to limit competition by controlling entry qualifications (Hospodárské noviny 19 January 1995, and 12 February 1999). Representatives of the profession were amazed at this suggestion (I. Pelikánová, Hospodárské noviny 25 January 1995), presumably unaware of its central place in Friedman's argument against the medical profession controlling standards of those practising medicine (Friedman 1962: Chapter 9).

Regional government was a bigger theme, as it figured in OF programmatic documents and in the constitution. The inherited structure of eight administrative authorities had been dissolved in 1991, but no agreement followed on how it should be replaced with new, self-governing authorities. The ODS preference was for a large number which would have little chance of challenging a central authority. Klaus anyway saw no urgency, arguing that genuine decentralisation should be directly to the citizen, meaning the greatest possible reliance on market relations and the minimum of bureaucracy. In the words of his press spokesperson, ‘do we want every second citizen to be a state official or a representative, so that there will be an even stronger bureaucracy?’ (J. Petrová, Lidové noviny 27 June 1994). In fact, the abolition of one layer of regional government was followed by a growth in employment in the state administrative structures by 77 per cent from 1991 to 1997. However, as Klaus pointed out, the precise merits of the case were not the issue. Regional administration was ‘a stale theme which lacks popular support’ (Rudé právo 24 June 1995). There were some who saw creating strong local government as the key to a functioning ‘civil society’, but the wider public showed little interest.

Organised interest representation was ultimately a more troublesome area. Klaus contemptuously dismissed trade unions and employers’ organisations as ‘a residue from socialism’ (Lidové noviny 5 November 1993). Unions should have no role outside the immediate workplace, but this had been ‘rather poorly understood’ when tripartite structures were established. It was ‘no small task to turn this back’ (Lidové noviny 18 April 1994). Klaus nevertheless made a serious effort after unions staged protest actions against a proposed reform of the pension system in December 1994. He was, however, held in check by his coalition partners, with the KDU–CSL taking the unions’ position seriously. The outcome was a restriction in the tripartite's competence such that it could not discuss the full range of economic issues (Myant et al. 2000).

The trend towards a centralised, unlistening government was reversed by the electoral weakening of the ODS in 1996, the subsequent intensification of economic difficulties, the emergence of divisions in its own leader-ship and a clear threat of rising social discontent. The first, albeit cautious, step towards institutionalising change was a restoration of the tripartite in its original form in July 1997. Klaus still had no interest in listening to what was said there, but his time as Prime Minister was anyway practically at an end.

The aftermath

Returning to the questions posed at the start, the sharp conflict around civil society reflected much more than two abstract views of the world. It concerned one of the central questions of Czech political development in the mid-1990s, but it also missed the crucial areas associated with interest representation and the political implications of privatisation. The ODS's position was closely tied to privatisation in which wide authority was left within ministries and a government freed from scrutiny by parliament or any outside body. Havel, coming from a position that ignored economic and social interests, pinpointed general themes of control over power which were not areas of central concern to the population.

The fact that Havel progressively nailed his colours to the anti-Klaus mast undoubtedly played some role in weakening the latter's prestige, but it was only one part of a process that began to reverse the concentration of power towards a dominant party. Ágh has referred to the party domination of east-central European politics as a phase that should give way to a broadening of inputs from outside the party system. Czech experience illustrates two points. The first is that party domination depended on a determined effort by a particular group to create the party that would aim to dominate and then to exclude others from political influence. The second is that opening up the political structure and creating a wider pluralism was itself the result of political battles in which a very diverse range of forces and pressures were involved.

The specific issues that concerned Havel have generally been addressed. A senate started operating after elections in November 1996, with an electoral system that leads to a different party composition from that of the main chamber. The creation of fourteen new regional authorities was approved in April 2000, with the ODS still hostile. The electoral system led generally to ODS domination: that might eventually presage changes within a party that had little previous experience of alternative centres of power. The tripartite, albeit not one of Havel's themes, has operated to give representative bodies direct access to government and the right to comment on relevant legislation before it is passed. The potential power of trade unions has thus opened the way for involvement of a wider range of interests. Privatisation, again not one of Havel's themes, has continued, but with more scope for open scrutiny of decisions.

It would therefore appear that much of the institutional framework for a ‘multi-layered’ civil society has been created, with channels for interest representation, more scope for the decentralisation of authority and more means of control over power. However, civil society in this sense is still not a theme that creates great public excitement. There has instead been something of a revival of interest in a conception that emphasises the informal sphere, with activities distinct from, or even opposing established parties and representative bodies. This may have partly reflected specific circumstances after the parliamentary elections of June 1998. The minority Social Democrat government clung to office in the following years thanks an agreement with the ODS. In exchange for a promise to oppose any vote of no confidence in the government, the main opposition party was helped into a number of key parliamentary posts and the Social Democrats agreed, among other concessions, to support a change in the electoral system to one closer to the first-past-the-post principle. This would have given a real chance for a single party to win an outright parliamentary majority. The method ultimately approved by parliament was deemed illegal by the Constitutional Court in 2001 as it was incompatible with the constitutional stipulation of elections by proportional representation.

This ‘opposition pact’ between the two largest parliamentary parties was presented as a pragmatic necessity and as the only feasible means to maintain a stable government. To many, however, it appeared to be keeping afloat a government that clearly lacked majority support and to confirm all that was distasteful with political parties. What might elsewhere have been secret deals between a few individuals now seemed to be reached in the full glare of publicity. Loyal party representatives were left to toe lines that must have jarred with their instincts.

This period saw a revival of ideas for a political life outside, or opposed to, existing parties. Initiatives emerged, some with directly political aims but others ostensibly to create an independent discussion forum. Among the most substantial was Dekujeme, odejdete (Thank you, now leave’), initiated as a petition in November 1999 by former student leaders from the events of November 1989. Their call was for the then current generation of political leaders to resign. It soon claimed 150,000 signatures of support. This and other initiatives were quickly confronted with a situation that differed substantially from that of 1990. Civil society, in the sense of an informal sphere distinct from the existing structures of power, could claim a base in past traditions and could win immediate support from part of the population. Before long, however, figures leading independent initiatives were being asked about their links to existing parties, about what constructive alternatives they could propose and about whether they too might not soon be forming a party. It remains to be seen whether the partial revival of ‘non-party’ political activity after 1998 will prove to be a minor, temporary episode or whether the strength of past traditions and a continuing level of distrust towards the ‘formal’ sphere mean that it will remain a more permanent feature of Czech political life.

Bibliography

Ágh, A. (1998) The Politics of Central Europe, London: Sage.

Brokl, L., Mansfeldová, Z. and Kroupa, A. (1998) Poslanci prvního ceského parlamentu (1992–96), Prague: Sociologický ústav AV CR, working paper WP98: 5.

Coase, R. (1960) ‘The problem of social cost’, Journal of Law and Economics, 3: 1–44.

Cohen, J. L. and Arato, A. (1992), Civil Society and Political Theory, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cox, R. (1999) ‘Civil society at the turn of the millenium’, Review of International Studies, 25: 3–28.

Ferguson, A. (1966) An Essay on the History of Civil Society 1767, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Fiala, P., Holzer, J., Mareš, M. and Pšeja, P. (1999) Komunismus v Ceské republice, Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

Fric, P. (2000) Neziskové organizace a ovlivhování vefejné politiky (Rozhovory oneziskovém sektoru II.), Prague: Agnes.

Friedman, M. (1962) Capitalism and Freedom, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Havel, V. (1988) Anti-political politics, in Keane, J. (ed.) Civil Society and the State, London: Verso: 391–8.

Havelka, M. (1998) ‘Nepolitická politika: kontexty a tradice’, Sociologický casopis, 34: 455–66.

Hayek, F. (1944) The Road to Serfdom, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hayek, F. (1984) 1980s Unemployment and Unions, London: Institute for Economic Affairs.

Husák, P. (1997) Budování kapitalismu v Cechách: Rozhovory s Tomásem Ježkem, Prague: Volvox Globator

Jicínský, Z. (1995) Ústavneprávní a politické problémy Ceské republiky, Praha: Victoria Publishing House.

Keane, J. (1988a) Democracy and Civil Society, London: Verso.

Keane, J. (1988b) ‘Despotism and democracy’, in Keane, J. (ed.) Civil Society and the State, London: Verso.

Klaus, V (1992) Procjsem konzervativcem ?, Prague: TOP Agency.

Masaryk, T. G. (1927) The Making of a State: Memories and Observations, London: Allen & Unwin.

Myant, M. (1993) Transforming Socialist Economies: The Case of Poland and Czechoslovakia, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Myant, M. (2000) ‘Employers interest representation in the Czech Republic’, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 16:1–20.

Myant, M. and Smith, S. (1999) ‘Czech trade unions in comparative perspective’, European Journal of Industrial Relations, 5: 265–85.

Myant, M., Slocock, B. and Smith, S. (2000) ‘Tripartism in the Czech and Slovak Republics’, Europe-Asia Studies, 52: 723–39.

Nielsen, K. (1995), ‘Reconceptualizing civil society for now: Some somewhat Gramscian turnings’, in Walzer, M. (ed.) Toward a Global Civil Society, Providence, RI and Oxford: Berghahn.

Niskanen, W. (1971) Bureaucracy and Representative Government, Chicago: Aldine Atherton.

Niskanen, W. (1994) Bureaucracy and Public Economics, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

O’Donnell, G. and Schmitter, P. (1986) ‘Tentative conclusions about uncertain democracies’, in O’Donnell, G, Schmitter, P. and Whitehead, L. (eds) Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Prospects for Democracy, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Otáhal, M. (1998) ‘O nepolitické politice’, Sociologický casopis, 34: 467–76.

Rueschemeyer, D., Stephens, E. and Stephens, J. (1992) Capitalist Development and Democracy, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Šamalík, F. (1995) Obcanská spolecnost v moderním státe, Brno: Doplnek.

Schumpeter, J. (1943) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, London: Allen & Unwin.

Seligman, A. (1992) The Idea of Civil Society, New York: Free Press.

Tocqueville, A. de (1980) On Democracy, Revolution and Society: Selected Writings, edited and introduced by J. Stone and S. Mennell, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tullock, G. (1976) The Vote Motive: An Essay in the Economics of Politics, London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Zpráva vlády o stavu ceské spolecnosti (Report of the Government on the State of Czech Society), January 1999.