5 Dual identity and/or ‘bread and butter’

Electronics industry workers in Slovakia 1995–2000

Introduction

This chapter characterises working life and industrial relations in two Slovak electronics plants based on a comparison of selected findings from the second (1995) and third (2000) phase of the international research project ‘The Quality of Working Life in the Electronics Industry’ (see note 1 in Kroupa and Mansfeldová in this volume for further details).

The principal source was a survey of workers' attitudes, using a standardised questionnaire, supplemented by data from other surveys and interviews with experts. In order to take into account the specific conditions of contemporary Slovakia, the findings are presented in conceptual and empirical context, with reference to system transformation, to economic conditions and the state of the labour market, and to the framework of industrial relations and social partnership in Slovakia during the period concerned.

Post-socialist transformation towards a democratic and capitalist system in the East European context involves a simultaneous and coordinated transformation of both the political and the economic system. Political reform itself involves a combination of two elements: constitutional guarantees of citizens' rights and development of the democratic right of participation (Offe and Adler 1991). The civil right to private property offered citizens — either as owners and employers or as employees — the opportunity to emerge from the relative homogeneity of the ‘working people’ (when everyone was employed by a monopolistic owner and employer — the state) via specific individual strategies. The other side of the coin was the exclusion of a further group of citizens — the unemployed — from the labour market.

Sociological treatment of these processes in Slovakia has encompassed biographical-interpretative approaches focusing on the behavioural and motivational dimensions of private business formation (Kusá and Tirpáková 1993) as well as on questions of social identity among the unemployed as expressed in their autobiographical narratives (Kusá and Valentšíková 1996); qualitative survey approaches have also been used, for example to examine the attitudes of young people towards enterprise, self-employment and unemployment (Macháček 1997; Roberts and Macháček 2001). However the prevailing methodology has involved standardised representative public opinion surveys of the (declared) values of individuals. Interpretation of the resulting data on generalised social attitudes has typically led to inferences about the (non-)adaptability of the population to the transformation from an authoriarian to a democratic political system, from a centrally planned to a market economy and from a state-dominated social system to modern social policies. Such interpretations have become the basis for constructing and measuring pro- and anti-transformation ‘potential’ in society, and as such they often lead to the conclusion that social adaptation to the system change demands primarily a change in socio-cultural stereotypes and attitudes. As a consequence, analysis of structural conditions and the macro-level economic and social framework of transformation, and above all of the social micro-sphere of plants, firms or workplaces has been neglected. For instance, the survey ‘Performance of entrepreneurial activities in transport’ (October 1992,426 respondents) produced the finding that the most important motivations for business start-up decisions were ‘better prospects for self-realisation’ (84 per cent) and ‘the opportunity to provide better services’ (78 per cent). Overwhelming verbal declarations for these kinds of values in surveys frequently overshadow possible structural determinants such as (in this case) ‘lack of perspective of the firm’ where the respondent worked (47 per cent) or ‘the need to come to terms with loss of work’ (46 per cent).1 This is problematic in an historical period in which research has pointed to the frequent occurrence of ‘cognitive breakdown’ (Krivý 1993) — the adoption of inconsistent beliefs, when individuals agree with contradictory statements or when preferences declared in surveys are disconnected from people's actual behaviour and from the development of the real situation at the level of the economy or society.2

In 1995, when there were already de facto more employees in the private sector than in the public sector (by 1,159,000 to 979,000) most employees questioned — regardless of which sector they themselves worked in — declared that they would prefer to be employed in the public sector or specifically by a state enterprise.3 For those who did not adopt this attitude, the attraction of work in the private sector was often connected with the desire (which may or may not have been actually realised) to set up their own firm. Jobs in firms owned by another (private) person were generally unpopular among workers. In other words the private sector was valued as a sphere of self-realisation by real or potential (co)owners/employers, while the public or state sector was valued by the majority of real or potential employees (Čambáliková 1997). Although this sample of workers was on balance positive about the benefits of privatisation for the economy as a whole, the overwhelming consensus was against their own firm's privatisation: 45.8 per cent felt that state ownership was the best guarantee of their firm's development when asked to choose from a range of options, the next most popular of which was ownership by employee shareholders with only 13 per cent (3.8 per cent favoured foreign ownership, and just 1.7 per cent supported the current management). The existence of such divergent opinion on privatisation in general and privatisation of one's own employing enterprise is all the more significant given the nature of the privatisation process in Slovakia, as a process realised and controlled by political elites that derived their legitimacy and competences from citizens on the basis of free elections. Employees of a particular firm were not asked their opinions except as voters, in which role they were more likely to express their views on privatisation in general.

Post-socialist transformation is not a nationally isolated process. Exogenous influences have played an important role in shaping the economic and political structures of transforming societies. The creation of an entirely new class of entrepreneurs and owners has been a political process, determined and directed by real actors. In contrast to its western version, the market economy that is emerging in Eastern Europe resembles ‘political capitalism’: it is a ‘xeroxed’ capitalism arranged and enforced by reform elites (Offe and Adler 1991). This has two consequences: firstly, the successful negotiation of this type of transformation depends politically on processes of democratic legitimation and social consensus building; and secondly, the transformation cannot be completed until it penetrates not just the form but also the content of the economy. It must encompass economic institutions, economic actors (individuals, firms and corporations) and ‘everyday’ economic practices.

On the political level, ‘the principle of citizenship begins with the estab-lishment of political regimes in which civil rights and civic participation can become necessary elements of the constitution’; while ‘modern social conflict is about attacking inequalities that restrict citizens’ full participation in the social, economic or political realm' (Dahrendorf 1991: 73). In this sense, the process of democratisation is also the process of establishing institutions that mediate citizenship in all its dimensions — on the one hand connecting citizens with the polis and on the other hand connecting citizens with the market, since democratic conceptions of citizenship stress that the rights of the citizen comprise political, civil and social or economic rights.

Economic democracy can be understood in a wider sense — as a democracy with the political aims of wealth redistribution and equal access to economic opportunities; but it also has a narrower meaning (in the sense of industrial democracy) — the participation of workers in the management and control of the production process, especially at plant level (Sartori 1993). At the start of the transformation in Slovakia, the sphere of political and civil rights was prioritised over the sphere of economic rights. This is reflected in social attitudes, where citizens' participation in the democratic process, as revealed both in their declarations and in their actual behaviour, is effectively reducible to the roles and the status of a political citizen. With the exception of social partnership and collective bargaining, participation is realised independently of economic activities and outside the working environment of citizen-employees. Industrial democracy at plant level remains a potential rather than an actual expression of democratic citizenship, which has so far run up against both economic and socio-psychological limits. Social partnership and social dialogue offer potential institutional solutions to this problem: they are tried and tested democratic means of participation in decision-making processes both in society and in the firm (mainly in connection with social policy, work conditions, wages and the status of employees). Simultaneously (and this applies especially to tripartite institutions at the macro level) they are a forum for extra-parliamentary social debate geared towards the creation of social con-sensus, and thus an instrument for the democratic but ‘non-political’ and ‘party-neutral’ legitimation of the transformation process in the economic and social spheres and in the sphere of industrial relations.

Social dialogue and social partnership in Slovakia

Since the institutionalisation of social partnership in the Slovak Republic, social dialogue has been accomplished at three levels:

1 the micro-level (the firm),

2 the meso-level (industrial branches and regions),

3 the macro-level (the tripartite).

At the beginning of the period of rapid social changes and system trans-formation, a certain institutional vacuum emerged. In the absence of intermediary structures between state and society, precipitately emerging political parties and other institutions tried to fill this vacuum. The institutions of social partnership and social dialoque were established at this time. Social partnership in Slovakia has been (in comparison with most European states with a market economy) institutionalisd in the specific context of a social structure homogenised by the socialist system, at a date (1990) when the main actors (employers' associations and standard trade unions) did not yet exist. The formation of the Council for Economic and Social Accord (as the tripartite council is officially known) was influenced at the outset not just by this relatively homogenised social structure, but also by the high political legitimacy and social prestige of the government after November 1989. Trade unions — burdened by their past as the ‘heirs of state-controlled unions’ and without a clear conception of the transformation — could not be a real social partner for the government. Employers and their associations were only just forming, with the state still having a near monopoly in terms of employment and enterprise. The government could therefore assume the dominant role in the tripartite. The social partners accepted the discourse of political elites on the need for the rapid creation of a ‘capital-creating class’ (enterpreneurs and employers), the need to increase the effectivity and competitiveness of the Slovak economy and reorientate it towards global and western markets, and the need to simultaneously maintain social peace. This systemic conception of social change initially enjoyed general societal support. Nevertheless the creation of the tripartite council could be considered a signal that the authors of the new political system realized that transformation in the sphere of work and collective labour relations would lead to tensions and that it would be necessary to create institutions in which conflicts could be resolved or prevented by negotiation.

After November 1989 the government strengthened its position through legislative changes: trade unions lost some of their co-decision making and control competences especially at the level of the enterprise. Attacks on trade union competences were probably motivated in part by the assumption that extensive union powers in enterprises could complicate the process of restructuring and privatisation. Nevertheless while trade unions gave up some of their rights and competences in the process of democratisation, they gained others, including the right to participate in tripartite negotiations and the exclusive right to represent employees at all levels of social dialogue (including collective bargaining). Privatisation made it possible for some former employees — the managers of former state enterprises — to became the new owners of privatised enterprises and thus to become employers. The Slovak government's preference for this form of privatisation reflected its increasingly close connections with an emerging employers' interest group. This also meant that the government could assume the support and loyality of employers in the framework of tripartite negotiations.

The remit for tripartite negotiations, according to its original statute, included economic issues, social issues, wages and work conditions, while the outcome of negotiations should be a ‘General Agreement’ governing conditions and relations in these spheres. However it only had the status of a ‘gentlemen's agreement’ — unlike collective agreements at the enterprise or branch level, the General Agreement had no legal, but ‘only’ political or moral force. The tripartite made it possible for social partners to participate in the resolution of problems connected with the transformation of society and work within the framework defined by their newly specified competences. It enabled them to take standpoints on legislative proposals, and the view of the tripartite council was presented in parliament as an explanatory attachment to each bill. Constitutionally, however, the social partners — including the government — have no guarantee that their agreement will become law, since parliament (the Slovak National Council) is the sovereign legislative power.

The systemic transformation of social and labour-law conditions, given above all by the Labour Code and the systems of social, health and old age insurance, has not yet been completed in Slovakia. The tripartite was conceived as an important forum for extra-parliamentary input into these problems, but also for dealing with questions which exceed the scope of enterprise collective agreements and the competences of their actors. It therefore remains relevant not least because the actual scope and extent of collective bargaining at the enterprise level is relatively narrow: the content of collective agreements is defined on the one hand by the Labour Code (conditions in a collective agreement cannot be at variance with the Code) and on the other hand by the legally enshrined competences of trade unions at the enterprise level. Adjustment of both these constraints (i.e. liberalisation versus regulation of industrial relations) has been one of the most important topics of tripartite negotiations. Trade unions used the tripartite to demand the legal codification of their own competences in relation to national or regional public institutions such as the emerging labour market institutions. In this way they managed to acquire some significant competences, especially in terms of participation in new public corporations such as social insurance, health insurance and pension funds. However governments, especially in more recent years, have not accepted many union demands, some of which were incompatible with a parliamentary political system (for example the demand for tripartite conclusions to be binding for the next phase of the legislative process).

Social partnership and social dialogue have been strongly conditioned by the history of privatisation. Government pledges in the course of social dialogue and social partners' demands towards government have to be harmonised with the latter's competences in conditions of ownership plurality. The state is no longer the monopoly employer and enterpreneur, and the difference between conditions in the public and private sectors is increasing. Moreover differentiation between branches and regions causes further problems for the coordination of negotiations at the national level, with the result that agreements passed at this level are more and more general and formalistic. In Slovakia the private sector now produces more than 80 per cent of gross domestic product and more than three-quarters of the workforce is employed by private companies. Thus, as a result of the economic transformation process, it is enterprise-level industrial relations which have the greatest significance, which provides employees and employers with greater scope to influence labour relations through legally binding bilateral collective agreements.4

The Slovak economy 1995–2000

In view of the standardised research methodology of the main survey data which this chapter draws upon, a consideration of economic and industrial development in the relevant period is necessary to provide both a contextual framework of working life (since workers' evaluation of the changes between 1995 and 2000 are reported in the survey), and also — given the specificities of Slovakia's economic and political development during the period — an important explanatory framework for the outcomes and changes identified.

Between 1994 and 1998 Slovakia achieved a relatively high, and among the transition economies the highest, rate of growth in GDP. However growth was achieved at the cost of disequilibrium that meant conditions for sustainable growth were never established, and a significant decline in the rate of economic growth occurred from 1998. This disequilibrium is characterised by an imbalance between final consumption expenditure and domestic production (as a volume of GDP): as a result gross domestic consumption has been higher than the productivity of the economy could sustain. Disequilibrium is to a large extent structurally conditioned: demand, which is naturally diversified, consists of mainly finished products, while supply consists of mainly unprocessed and intermediate products. In other words the Slovak economy suffers from a persistently low degree of product finalisation. The greatest proportion of this internal disequilibrium was accounted for by expenditure in the state administration and in the sphere of investments. Capital investment saw an enormous growth between 1996 and 1998, but was dominated by infrastructural investments, especially energy generation (including the completion of a nuclear power station) and transportation (highways). Investments in manufacturing industry were directed mainly to less sophisticated branches, contrary to the objectives of state industrial policy, which sought to change the structure of industry in favour of production with high value added and low material and energy intensity. Thus the existing disadvantageous production structure was even further entrenched.

The inefficient direction of investments was supported by industrial policy, which — through tax allowances and large guarantees for loans to industry — created a soft environment with no pressure towards higher efficiency and more competitive production programmes. This further exacerbated the state budget deficit, which in turn fed directly (through state expenditure and loan guarantees) and indirectly (through tax allowances) into the widening of the gap between consumption and production. Internal economic disequilibrium also fed into external disequilibrium in terms of a deficit of the current account of the country's balance of payments. Foreign currency reserves were used up, and the exchange rate of the Slovak crown fell. Among the contributory factors here were the relatively high share of foreign loans, the predominance of short-term finance within the overall structure of capital and finance sourcing, and the low volume of foreign direct investments. The obvious way to redress these imbalances would involve sticking to a sustainable balance of payments deficit and maintaining high-quality portfolios within capital and financial accounts, which should be restructured away from loans in favour of foreign direct investments.

Table 5.1 Foreign direct investment inflows in CEFTA countries

The low level of foreign investments in Slovakia has been partly caused by the transformation of property relations, specifically by the overt preference for domestic applicants when selling industrial companies owned by the state. During the prime ministership of Vladimír Mečiar the favouring of domestic buyers and owners in the privatisation process manifested itself in growing mistrust and caution on the part of foreign partners. As a result, the Slovak economy showed the lowest level of participation in international capital flows within the region.5

Wages

In 1997 average monthly wages in Slovakia for employees with basic and primary education reached only €175 (when recalculated per full-time occupation), which is 8.2 times lower than the average income in EU countries; for employees with secondary education the figure was €237 (8.6 times lower than in the EU); and for employees with university education it was €501 (5.4 times lower than the EU mean). In 1999 the official minimum wage was €1,162 in Luxembourg, €357 in Portugal, but just €94 in Slovakia.6 The level of real wages in Slovakia in 1999 was still below that at the start of the transformation in 1989. In fact real wages fell further in 1999, by 3.1 per cent, mainly due to price increases and rising costs of housing, water, electricity, gas, health care services, recreation and culture.

Prices

The level of inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, reflected the gradual adoption of administrative and economic measures to deregulate prices, increases in prices which continued to be centrally regulated, and tax rate changes (especially value added tax and excise duties). Between 1995 and 1998 inflation remained below 7 per cent, but in 1999 it increased to almost 15 per cent.

Employment

In the early phase of the transformation process employment fell mainly as a consequence of the conversion of the armaments industry and the collapse of East European markets. Further decreases in employment were connected with the processes of enterprise restructuring. In the 1993–9 period economic growth had no positive impact in terms of job creation. While the increase of GDP was 32.9 per cent in the period 1994–8, the employment rate increased by just 1 per cent. That means that GDP growth was obtained thanks to increasing labour productivity, (up 31.6 per cent in the same period). However this was achieved simply by enterprises laying off surplus labour.7

During the period surveyed, employment gradually decreased in the public sector (by 24 per cent) and increased in the private sector (by 15 per cent). Accordingly the share of the private sector in total employment grew from 40.5 per cent in 1994 to 65.2 per cent in 1998. The branch structure of employment has also changed. The branch with the highest number of employees is still industry, but its share of total employment fell from 30.3 per cent in 1995 to 29.6 per cent in 1999. The greatest falls in employment were recorded in agriculture, industry and construction. On the other hand the number of employees increased in public administration, health, public and social services, education, insurance and banking.

Unemployment

The unemployment rate increased by approximately 6 per cent between 1995 and 1999 (from 13.1 per cent to 19.2 per cent), although this is partly explainable by demographic trends: the economy failed to create sufficient demand for the increased supply of labour entering the market. This shortfall has been widening: whereas in 1997 the annual increase in new jobs was 160,000, only 90,000 new jobs were created in the year to December 1999. The most vulnerable groups in the labour market are young people without work, women taking care of their children, people with low education skills and physically disabled people. They form the core of the long-term unemployed. So-called social unemployment is also a problem, since groups on the lowest wages cannot achieve higher incomes through the labour market in comparison with unemployment benefit or other social benefits. The ratio between the minimum wage, unemployment benefit and social support is 4,000 : 3,456 : 3,093.

Regional differences in the unemployment rate have been deepening. At the end of 1999, when the national registered unemployment rate peaked at 19.18 per cent, the difference between the highest unemployment rate (Rimavská Sobota district — 37.36 per cent) and the lowest one (Bratislava district — 4.21 per cent) was 33.15 percentage points. Unemployment trends are alarming from the perspective of regional development: in eleven districts unemployment is more than 30 per cent and in 39 it is more than 20 per cent (out of seventy-nine districts in Slovakia).8

Labour market policies

Labour market policies consist of a system of social support and social assistance provided to citizens, enabling them to participate in the labour market. Today the authorities involved in labour market policies are the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and the Family and the National Labour Office (NLO).According to Act no. 387/1996 on employment the NLO was established as a public corporation on the principle of tripartism, based on the cooperation and co-responsibility of the social partners. The NLO is funded on an insurance principle, and is separate from the state budget. Labour market policies in Slovakia rest on redistributive and social solidarity principles, and consist of two components: passive labour market policy (especially unemployment benefit and payments to health and social insurance funds for certain categories of registered unemployed) and active labour market policy (the primary objective of which is to assure the right of citizens to suitable employment through the creation of new jobs, the maintenance of existing jobs and the establishment of conditions necessary for professional and spatial mobility). The resources for active labour market policy depend directly on the expenses for passive labour market policy in a given year, because the right to unemployment benefit is a legal right under the Employment Act. Given that mandatory expenditure on passive labour market policy has been increasing, the relation between outgoings on active and passive labour market policy has fallen from 178.7 per cent in 1995 to 140.1 per cent in 1996, 77.7 per cent in 1997 and 41.7 per cent in 1998.9

Working time

The duration of working time (per year or per week) is comparable with European Union countries, but the flexibility of working time is lower. The Slovak labour market is characterised by the low number of employees who work part-time (in 1999 only 2 per cent of all workers — the EU average was 17 per cent in 1997). Besides demonstrating the low flexibility of work patterns this also reflects the fact that the earned income for parttime work is insufficient to cover average living costs in Slovakia. In December 1999 a new regulation on part-time work was written into the Labour Code, bringing Slovak labour law into line with European Council resolution 97/81/ES on part-time working, and its aim is to increase the share of part-time workers.

In 1999 District Labour Offices permitted 7,191,267 over-time hours above the limits set by the Labour Code, equivalent to jobs for 3,596 additional workers. Nevertheless tighter regulation by Labour Offices saw the number of over-time hours permitted decrease in 1999 in comparison the previous year, when 18,602,896 hours were approved — equivalent to 9,301 jobs.10

The Slovak electronics industry 1995–2000

As already noted, Slovak industry is characterised by a strong dependency on traditional industries and too low a share of modern industries. Slovakia's specificity is the fact that industrial policy has to be implemented in a situation where much of the economy requires restructuring, meaning both the winding down of ineffective companies and industries and a shift of economic activity into new industries and areas. An indirect indicator of the level of restructuring is the ability of Slovak enterprises to succeed in foreign markets. Electronics enterprises saw exports grow by a factor of four during the last four years. Yet despite these increases, Slovak producers suffer from low competitiveness in foreign markets. According to an analysis by the Ministry of the Economy only 18 per cent of total exports are competitive in quality, with a further 29 per cent offering ‘standard’ quality and able to succeed on grounds of price. The remainder — more than half of production for export — is problematic from the viewpoint of competition. The problem is related to the low level of product finalisation: ‘this is caused above all by the tendency of firms with foreign participation to utilise overwhelmingly components originating outside Slovakia in the production of the final product’, claims A. Lancík, general secretary of the Union of the Electronics Industry of the Slovak Republic (the sectoral employers' organisation). Despite recent increases in the added value of production, labour productivity per employee in electronics enterprises still falls behind average productivity in industry by as much as 30 per cent. The reason lies in a continuing high share of manual labour. Slovakia's cheap labour force remains its strongest competitive advantage, and in contrast with the decrease of employment in industry as a whole, electronics enterprises show employment growth, and today they employ approximately 8 per cent of workers in industry.

The electronics industry in Slovakia has been privatised: since 1996, all enterprises in this branch have been in private hands. The share of firms with foreign participation is approximately 85 per cent of total branch production, and much of this foreign capital is represented by major firms such as Siemens, SONY, ALCATEL SEL, Motorola, Bull, ABB, OSRAM and Emerson. In 1999 investments in the branch reached three billion Sk, an increase of 44 per cent on 1998, and these growth trends are expected to continue. Capital investment also depends heavily on foreign firms. But ‘although the increases have been relatively high, we cannot consider this level of investment as sufficient, because the needs of electronics enterprises are higher’, according to the analysis of the Ministry of the Economy.

From dual deviation to dual identity?

The questionnaires distributed in the two sample electronics plants revealed one very important change in industrial relations in the last five years: whereas in 1995 there was a tendency towards dual deviation (where workers identify neither with the management nor with their trade union), in 2000 dual identity (where workers identify with both plant management and trade unions) clearly predominated.11

One-sided types of identity (oriented towards either management or union) remained almost unchanged and applicable to only a small minority of workers. On the contrary Slovak experience seems to confirm the prevailing tendency observed in the previous phases of the international research, implying that East European workers too prefer either dual deviation or dual identity to a one-sided type of identity.

The explanatory hypothesis which emerges is that management and unions no longer constitute alternative sources for identification and loyalty. In the traditional model of industrial relations based on class antagonism, employee identity is supposed to be oriented towards either management or unions. ‘Dual identity’ could result from the heralded shift from class-based conflict to a model of industrial relations based on organisational integration.

The simple labour contract and the service relationship

In the relevant sociological literature (e.g. Giddens 1999: 268, 271) two basic types of employment relations are distinguished: the simple labour contract and the service relationship. The simple labour contract is charac-teristic for the situation of workers in the early phases of western industrial-isation and is associated with the traditional type of confrontational industrial relations. This type of employment relationship implies that wages are exchanged for labour, the employee is easily replaceable at low cost, and the tie between employee and employer is limited to the wage. The service relationship, by contrast, is based on trust and implies dependency relations between employer and employee. In this type of industrial relations it is assumed that work has become more autonomous and multi-skilled and the product market more fluctuating and unpredictable. These developments force firms and their workforces to increase their capacity as collective actors to adapt to the changing environment in a

Table 5.2 Distribution of four types of workers' identity (per cent)

| Dual identity | Management-sided | Union-sided | Dual deviation | |

| 1995 | 15.1 | 12.5 | 10.1 | 39.3 |

| 2000 | 40.2 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 9.8 |

Source: Ishikawa et al., Denki Rengo Survey, 1995 and 2000

flexible way. One implication is that it has become vital for management to create feelings of participation and identity and to train workers with a broad range of skills who are committed to their company. In other words a larger proportion, especially among unionised workers, have gradually been offered a ‘service relationship’, and the industrial relations system has therefore been transformed into a more cooperative one.

Is dual identity, as manifest in contemporary Slovakia, comparable with trends observed in West European countries? Are the causes of its development identical? Which general and which specific aspects in what combination lead to the emergent feelings of participation, community and identity found among these Slovak workers? Is a ‘service relationship’ really on offer to a larger proportion of the unionised workforce in Slovakia in the early twenty-first century? Are Slovak workers in electronics plants trained and treated in such a way as to enable them to acquire a broad range of skills and to become committed to their company? Our field observations and interviews with workers in the chosen firms, together with our analysis of the data obtained, indicate how difficult it is to give unambiguous answers to these questions. Nevertheless we can say that changes in workers' identity in Slovakia have been influenced not only by ‘internal’ factors (changes in the quality of working life) but also by ‘external’ factors, including: changes on the macro-level (especially the high level of unemployment and generally low level of wages); changes at the branch level (connected with the need for restructuring and modernisation); and changes at the level of the plants themselves, both of which have been transformed into companies with foreign capital involvement, and both of which belong to the most successful and stable firms in Slovakia.

Working life in the sample firms: what has changed since 1995?

Since 1995 workers' identity in both firms has switched from dual deviation to dual identity. In general workers' tendency towards dual identity is highly dependent on their satisfaction with work, job security, wages and career opportunities in the firm. It is associated with the development of a workforce with a broad range of skills and with the introduction of a ‘service relationship’ for a larger proportion of unionised workers (Ishikawa and le Grand 2000: 45). The following changes were observed within the various components of workers' firm-level identity.

Changes in evaluations of job satisfaction

The generally positive evaluations of working life which were recorded in 1995 have further improved: no respondent declared that he/she was absolutely dissatisfied with working life in 2000. In comparison with 1995 the satisfaction of workers with job security and welfare provision has increased

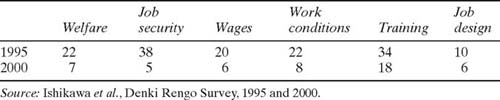

Table 5.3 Satisfaction with working life (per cent)

Table 5.4 Satisfaction with different aspects of work (per cent)

| 1995 | 2000 | |

| Work conditions | 32.4 | 63.5 |

| Work load | 46.7 | 47.7 |

| Trust managers--employees | 17.5 | 37.3 |

| Wages and remuneration | 12.4 | 25.3 |

| Promotion prospects | 18.5 | 19.9 |

| Training | 26.0 | 27.0 |

| Job security | 15.6 | 41.3 |

| Welfare provision | 21.9 | 56.8 |

| Relations with supervisor | 58.4 | 49.6 |

| Relations with co-workers | 87.6 | 82.7 |

Source: Ishikawa et al., Denki Rengo Survey, 1995 and 2000

almost threefold; satisfaction with pay and fringe benefits, with work conditions, with trust between managers and employees almost doubled. Satisfaction with relationships between co-workers and with work-loads stayed roughly the same (and relatively high). A constant relatively low level of satisfaction, on the other hand, applied to evaluations of promotion opportunities, training and retraining.12 Relationships to supervisors saw a slight deterioration, but remained satisfactory for half the workforce.

Changes in evaluations of the work process

According to our interviews with experts (including trade union representatives at the plant-level) the work tasks of most workers — and especially blue-collar workers — in the two firms have not become any more autonomous or multi-skilled. Unskilled work is the norm, especially for female blue-collar workers. The proportion of workers who feel that they can control what they do at work has decreased more than threefold. The number of workers who are convinced that they can make use of their abilities in their work and/or learn new skills is also lower. The number of workers whose work is dictated by machinery has increased. But despite these findings fewer workers than in 1995 consider their work to be repetitive, and overall satisfaction with working life is higher.

Table 5.5 How true are the following statements about your work? (per cent)

Changes in workers' relationship to the firm

The level of both moral and instrumental commitment to the firm seems to be high and stable. Only 10.7 per cent of workers in 1995 and 4.2 per cent in 2000 expressed indifference to company affairs.

Changes in evaluations of interest representation

The measure of agreement with decisions by both plant-level trade union organisations and plant management has increased significantly in the sample firms.

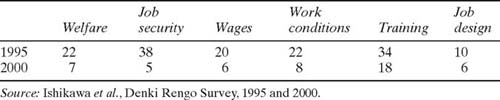

Table 5.6 How far do the decisions of your local union reflect your opinions? (per cent)

Table 5.7 How far do the decisions of management reflect your opinions? (per cent)

| Membership | Agreement with union (very+fairly well) | Participation (often+ whenever possible) | |

| 1995 | 75 | 28 | 8 |

| 2000 | 67 | 64 | 18 |

Source: Ishikawa et al., Denki Rengo Survey, 1995 and 2000

Despite a slight decrease in union membership during the last five years, the level of agreement with plant-level trade union policy (i.e. the conviction that decisions by the union reflect workers' own opinions) has increased significantly. In both firms, however, the level of direct participation in trade union activities is relatively low, which is related to the type of activities most typically undertaken by unions: above all they are concerned with collective bargaining and the operation of a ‘welfare service’, both of which are ‘expert’ activities, and have practically become professionalised in the sample firms. The relatively low level of direct participation by trade union members is thus explained by the satisfaction of employees with the representation and protection of their interests in the areas which they consider to be key; their passivity as social actors is only a secondary explanation.

The most important tasks for the trade union according to the opinion of workers were: securing wage increases (in 2000 90.6 per cent of trade union members considered this very important) and protecting job security (87 per cent very important). A secondary set of tasks for unions (according to workers' ranking of their importance) is connected with holidays and leave (59 per cent), welfare services (57 per cent) and the work environment (50 per cent). Only around 20 per cent of workers attached great importance to activities connected with work loads and work methods, working time and work organisation, or education and training. A similarly low proportion (18 per cent) considered it very important to increase the influence of the trade unions over, and/or to broaden the scope for workers' participation in, management policies.

These trends in workers' attitudes toward unions suggest at least a partial modernisation of the ‘residual’ identity associated with unions' welfare function under the previous regime (Slocock and Smith 2000: 219). Our analysis showed further — and this may be one of the main reasons for the inception of a ‘dual identity’ in both firms — that plant managements as well as trade unions have adopted a role in the areas considered most important by workers and where they felt an absence of interest representation in the past, job security and wages. In the sphere of job security workers consider plant managements to be the single best representative of their interests, whereas in the sphere of wages they look to the trade union together with management (especially their immediate superior); in the field of social welfare their preferred representative is the trade union. The only spheres in which as many as half the workers felt the absence of any subject to represent their interests were promotion and career development and training and education. Thus from the perspective of trade unions, positive trends (strengthening perceptions of trade unions as a collective actor which represents employee interests well) are observable in the spheres of wages and work conditions, job security and social welfare issues. On the other hand, the last five years have seen a loss of confidence in the influence of trade unions in the spheres of training and education

Table 5.9 Representational deficit on labour issues (percentage of workers who answered ‘nobody’ when asked ‘Who best represents your interests in the following aspects of working life?’)

and job design. The absence of representation which workers feel in these spheres has not however had any major influence on their satisfaction with working life or on their overall identification with trade unions and management in the sample firms.

Worker participation and industrial relations in the sample firms

Only one trade union organisation exists in each of the firms, affiliated to the main metalworkers' union OZ KOVO, the strongest trade union among all forty in the Slovak Trade Union Confederation. Both organisations can boast above average unionisation rates: in comparison with the average rate for the entire Slovak labour force of 35 per cent, firm A's workforce was 55 per cent unionised in 1998,60 per cent unionised in 1999 and 45 per cent unionised in 2000; in firm B the workforce is even more strongly organised, with more than 92 per cent union members from 1996 to 1999, dropping to 80 per cent in 2000, which, according to A. Rakušan, chairman of the trade union organisation in firm B, was due to the recruitment of new workers on temporary contracts:

New legislation introduced in December 1999 makes it possible to employ workers for a period of six months and then to extend their contracts for a further six months. Among workers who were employed on permanent contracts 90 per cent are trade union members, but among the employees working in the “2×6 months” regime the figure is only 20 per cent. These are usually unskilled workers, especially women.

In both plants a collective agreement is signed between the plant-level trade union organisation and the management. On the branch level a higher-level collective agreement (KZVS) is signed between OZ KOVO and the Union of the Slovak Electronics Industry. Trade union leaders on the plant level consider collective bargaining as their main task, wherein their main aims are to achieve the best possible conditions, especially in the spheres of wages, social conditions and labour relations; matters relating to the implementation and policing of collective agreements constitute their second main area of concern.

In both plants unions are financed from a combination of membership fees (1 per cent of members' salaries) and company subsidies, which cover room rent, telephone bills and the wage of the union chairman — according to the KZVS firms which employ more than 450 employees are obliged to pay the salary (equivalent to the average wage within the firm) of one trade union representative, while two union representatives are entitled to support if the firm has more than 900 employees. The employer cannot terminate the contract of an elected union representative either during his/her term of office or for a further year. The effectiveness of collective bargaining is indicated by the fact that no labour dispute occurred in either firm during the period 1995–2000.

Conclusions

Our evaluations of work and the firm are inevitably conditioned by the wider context of economic and social conditions and the state of the domestic labour market. The restructuring of industry and the transformation of the economy have significantly influenced the Slovak electronics industry as a sub-system, and the social costs of transformation have also hit workers in this branch. The workers in the sample firms are not immune to the effects of rising unemployment, falling real wages and the appearance of poverty in Slovak society. For them — and for contemporary Slovakia — Kulpiñska's description of another work collective and her accompanying analysis of the transformation of working life in Central Europe holds true: ‘These employees … belong to the winners — they have jobs, and they are quite well paid … Despite this, their opinions are clearly influenced by the general situation, which involves growing insecurity and sometimes the threat of losing one's job’ (Kulpiñska 2000: 203).

The transformation process is connected with new challenges and adapt-ations. New foreign management teams, which have come into both sample firms, bring new techniques of human resource management, cultivate new types of labour relations and could improve the quality of working life. But more immediately they have come to be perceived by employees as the guarantors of their jobs and of the prosperity of the firm. For in the year 2000, our findings suggest, Slovak employees' expectations from both management and trade unions remained on the level of ‘bread and butter’ issues — and they were grateful for this much. For bread we can read jobs, and for butter wages: jobs are a fundamental priority for workers in a country where unemployment exceeds 20 per cent and in a sector where essential modernisation is not yet complete; wages are higher in these enterprises than the average for a sector whose comparative advantage is cheap labour costs, and usually only become a meaningful demand after the entry of foreign capital (which is presented by political and economic elites and in the media as a condition for current stability and future prosperity). The German and French owners of these two firms are amenable to trade unions, progressive in the application of new human resource management approaches and at the same time have preserved existing standards of enterprise welfare services. Although they have provided job opportunities for blue-collar workers they have not as a rule offered more autonomous and multi-skilled work, nor prospects for career development, personal and professional growth. Participation in management and union involvement in co-decision-making likewise remain issues of secondary concern among these workers. Despite this foreign employers have managed to engender in their workforces a commitment to the firm and a feeling of job satisfaction, simply by providing the chance to earn one's daily bread through work.

Our research findings therefore point to a certain discrepancy between Slovak and ‘western’ forms of dual identity, which is unlikely to be eliminated as long as the contemporary phase of economic globalisation reproduces patterns of core-periphery relations which impose severe constraints on the potential of local actors in countries like Slovakia.

Notes

1 Source: Názory 1992, no. 4. Respondents had the option of choosing more than one of the alternatives.

2 For instance, according to the survey Contemporary Problems of Slovakia in May 1994 (FOCUS Bratislava) 79 per cent of the public agreed with the opinion that ‘the state should provide a job for everyone who is willing to work’; 69 per cent agreed that ‘economic changes should proceed slowly to prevent unemployment’; 57 per cent thought that ‘state ownership of enterprises should predominate’; and 48 per cent thought that ‘prior to 1989 the economy required only minor changes’.

3 According to the EU-sponsored survey ‘Strategies and Actors of Social Transformation and Modernisation’ (carried out in the summer of 1995 by the Institute of Sociology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences on a random sample of 956 adults aged 20–59):

If it were up to you would you like to:

Work in a private company 12.3%

Work in a state-owned company 56.3%

Work in your own company 19.7%

Work abroad 10.5%

Not work at all 1.2%

Source: Transformation and Modernisation. Codebook 1995.

4 Collective bargaining is regulated by Act no. 2/1991 on collective bargaining. This Act shapes the collective bargaining process between trade unions and employers, defining a collective agreement as ‘a bilaterally drawn up document which is legally binding and determines the individual and collective relations between employees and employers as the rights and responsibilities of social partners’.

5 On the other hand it should be noted that a high share of foreign direct investment in neighbouring countries was channelled into the so-called natural monopolies, which were still owned by the state in the relevant period in Slovakia. The sale of even minority stakes in these companies would produce a change in this indicator in favour of Slovakia, since such one-off capital inflows have already occurred in the other countries. The post-1998 government approved a new strategy which openly supports the entry of foreign capital.

6 Source: Social Trends in the Slovak Republic 2000.

7 Source: Employment in the Economy of the Slovak Republic — entrepreneurial reporting data.

8 Source: The Ministry of the Economy of the Slovak Republic.

9 Source: OECD figures.

10 Source: National Labour Office.

11 As early as the 1950s Japanese researcher Odaka Kunio (Odaka 1953) revealed the predominance of workers with ‘dual identity’, based on empirical surveys of workers' attitudes. More recent research projects led by Akihiro Ishikawa have analysed international data obtained from the Denki Roren research project in 1984–5 (Ishikawa 1992) and (together with C. le Grand) from the Denki Rengo research project in 1995 (Ishikawa et al. 2000) in an attempt to ascertain whether ‘dual identity’ is universal in modern society or particular to Japan.

12 Education and training schemes operated by both firms consist of introductory courses for newly employed blue-collar staff lasting from one week to six months, and for newly employed technical staff usually six months. Internal company training is also organised for more experienced staff. In the past five years approximately 60 per cent of blue-collar workers, 90 per cent of technical staff and 100 per cent of managers have participated in training courses of at least a week. The content of training, its length and the selection of participants are determined by management.

Bibliography

Bulletin Štatistického úradu SR [Bulletin of the Slovak Statistical Office] (1995) 12.

Čambáliková, M. (1996) ‘K otázke občianskej participácie v transformujúcom sa Slovensku’, Sociológia vol. 28 no. 1: 51–5.

Čambáliková, M. (1997) ‘Utváranie občianstva zamestnancov a zamestnávatel'ov’ in Roško, R., Macháček, L. and Čambáliková, M.Občan a transformácia, Bratislava: SÚ SAV: 100–34.

Dahrendorf, R. (1991) Moderný sociálny konflikt, Bratislava: ARCHA.

Giddens, A. (1999) Sociologie, Praha: Argo.

Ishikawa, A. (1992) ‘Patterns of Work Identity in the Firm and Plant: An East-West Comparison’, in Szell, G (ed.) Labour Relations in Transition in Eastern Europe, Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Ishikawa, A. and le Grand, C. (2000) ‘Workers’ Identity with the Management and/or the Trade Union', in Ishikawa, A., Martin, R., Morawski, W. and Rus, V. (eds) Workers, Firms and Unions 2: The Development of Dual Commitment, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Ishikawa, A., Martin, R., Morawski, W. and Rus, V. (eds) (2000) Workers, Firms and Unions 2: The Development of Dual Commitment, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Krivý, V. (1993) ‘Problém názorovej inkonzistencie a kognitívnej dezorientácie’, in Aktuálne problémy Slovenska po rozpade ČSFR, Bratislava: FOCUS.

Kulpiñska, J. (2000) ‘Transformation of Working Life in Central Europe’, in Ishikawa, A., Martin, R., Morawski, W. and Rus, V. (eds) Workers, Firms and Unions 2: The Development of Dual Commitment, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Kusá, Z. and Tirpáková, Z. (1993) ‘O rozhodovaní sa pre dráhu súkromného podnikania’, Sociológia vol. 25 no. 6: 547–64.

Kusá, Z. and Valentšíková, B. (1996) ‘Sociálna identita dlhodobo nezamestnaných’, Sociológia vol. 28 no. 6: 539–57.

Macháček, L. (1997) ‘Mládež a tri výzvy modernizácie Slovenska’, in Roško, R., Macháček, L. and Čambáliková, M.Občan a transformácia, Bratislava: SÚ SAV: 57–100.

Macháček, L. (1998) Youth in the Processes of Transition and Modernisation in the Slovakia, Bratislava: SÚ SAV.

Ministry of the Economy of the Slovak Republic Employment in the Economy of SR. Online. Available HTTP:http://www.economy.gov.sk.

Ministerstvo práce, sociálnych vecí a rodiny SR (2000) Social Trends in the Slovak Republic. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.employment.sk

National Labour Office, Annual Report 2000.

Názory (1992) Informačný bulletin, no. 4, Bratislava: Ústav pre výskum verejnej mienky pri Slovenskom štatistickom úrade [Institute for Public Opinion Research at the Slovak Statistical Office].

Odaka, K. (1993) Science of Human Relations in Industry, Tokyo: Yuhikaku.

Offe, C. and Adler, P. (1991) ‘Capitalism by democratic design?’, Social Research vol. 58 no. 4: 865.

Roberts, K. and Macháček, L. (2001) ‘Youth Enterprise and Youth Unemployment in European Union Member and Associated Countries’, Sociológia vol. 33 no. 3: 317–29.

Sartori, G. (1993) Teória demokracie, Bratislava: ARCHA.

Slocock, B. and Smith, S. (2000) ‘Interest politics and identity formation in post-communist societies: the Czech and Slovak trade union movements’, Contempor-ary Politics vol. 6 no. 3: 215–30

Transformation and Modernisation. Codebook 1995 (1995), Bratislava: Sociological Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences (internal material).

WIIW (Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies) (July 1999) Foreign Direct Investment in Central and East European Countries and the former Soviet Union, Vienna: biannual report. Online. Available HTTP:http://www.wiiw.ac.at/e/fdi_data.html