3 Civic Forum and Public Against Violence

Agents for community self-determination? Experiences of local actors

So are you saying we don’t have any honourable politicians?

— We do, but they are the ones who lack support…. People somehow don’t appreciate them …

Could it have turned out differently?

— Probably not. I thought this country was a lot better prepared for the fall of communism, that its moral condition was a lot better. But it isn’t.

You live in a small village [near Trnava] where most people support HZDS. How do you get along?

— The locals believe sweet-sounding slogans and don’t realise what influence they have on things. They tolerate me, they even listen, but they treat me as an eccentric.

(Interview with actor and folk singer Marián Geišberg, Domino fórum no. 4, 2002)

At present legal and political methods are highly effective and we must not abandon them. But nor should we neglect other strategies… Fundamental aspects of our environment will change for the better only via a positive road: by personal connection and personal example, through understanding, reciprocity, trust, openness, cooperativeness, interest in others, strength of personality.

(Jan Piňos, Czech environmentalist, ‘Trvale udržitelné hnutí’, Sedmá generace no. 9, 2000)

If it were not for us [mayors and local councils], instilling a certain calm and peace in the municipal sphere against a background of terrifying problems, this state would turn into Argentina.

(Peter Modranský, mayor of Trenčianske Teplice in Slovakia, Obecné noviny no. 22, 2002)

Introduction

Civic Forum (OF) and Public Against Violence (VPN) warrant attention for their historical role in extricating their respective societies from communism and formulating a ‘route map’ for democratic transformation. In addition they are remarkable as social phenomena characterised by mass involvement, penetration down to the grassroots and the geographical peripheries of society, for the spontaneity with which people formed and joined local groups, and, not least, for a certain experimental quality of the politics they pursued. They embodied a participative type of politics based on a loose, movement-type structure without formal membership, on decentralised decision-making and a commitment to devolving self-governing powers to a wide range of spatial and functional constituencies, and on dialogue, partnership and non-partisanship. In Czech and Slovak the term ‘non-political politics’, derived from the pre-1989 dissident discourse and associated above all with Václav Havel, has become a shorthand for such a political philosophy. In his 1978 essay ‘The Power of the Powerless’, Havel had dismissed ‘traditional mass political parties’ as ‘structures whose authority is based on a long-since exhausted tradition’, and instead spoke up for ‘organisations emerging ad hoc, imbued with fervour for a specific goal and disbanding upon its attainment’ — a vision of political organisation echoing new social movement theory, and as challenging to conventional parliamentary systems as to what Havel called the ‘post-totalitarian’ regime in communist Czechoslovakia. Political structures, he went on, ‘ought to emerge from below, as the result of authentic social self-organisation’ (Havel 1990: 61–2). He was not alone in his dissident reflections — the Hungarian Gyorgy Konrad's concept of ‘anti-politics’ was likewise an attempt to transcend established political and polito-logical traditions — but nowhere else in Central and Eastern Europe were such ideas translated into political practice to the same extent as in Czechoslovakia in the first year following the collapse of communism.

It is worth recalling the degree of utopianism and exceptionalism associated with this concept at the outset of the post-communist era. In late January 1990 a key VPN document boasted:

The euphoria of the first days after 17 November is slowly fading: we are now facing the need to transfer the political changes into everyday life. But even now we need not forget what it was that made us interesting for the world… . Evidently it was because we carried out [our revolution] spontaneously, from below, through the rediscovery of our own humanity and our identity as a state,… and that we showed a Europe, exhausted by the thrust and counter-thrust of political parties which increasingly bypass people, that civility can still be part of elementary human behaviour, as long as human beings act with intentionality

(‘Predstava o krajine’, verejnost' no. 9,1990)

Given these characteristics and these claims, it is particularly relevant to examine an as yet little understood and poorly documented aspect of these movements' short existence, namely their functioning in and impact upon local communities. Not only would this give us a better indication of the level of their actual penetration, participativeness, decentralisation and spontaneity; there are good reasons for supposing that a ‘non-political politics’, although it was displaced at the national level after the first experiences with parliamentary ‘realpolitik’, had a more lasting relevance to local democracy, found a more receptive social milieu within small rural municipalities in particular, and had greater potential benefits in such communities. On the basis of a series of Czech empirical studies of local democracy, Kroupa and Kostelecký concluded, ‘It is evident that a certain mistrust of classical political parties, characteristic of national political life in the period immediately following the change of regime, persisted much longer at local level’ (1996: 114) In other words the notion of a ‘non-political politics’, although originating in urban intellectual circles, chimed with social attitudes prevalent in rural or small town communities, suspicious of all political ideologies and convinced that local government is an essentially ‘non-(party)political’ affair. This belief, which can partly be attributed to a post-communist reaction against the party, is founded on the assumed non-conflictual character of local issues, such that the task of local political representatives is to represent and/or mobilise a unified all-community interest, rather than to manage the interaction of competing interests. The continued development of such a politics following the demise of OF and VPN in 1991 has prompted some commentators to suggest that local self-government represents the most successfully democratised ‘power container’ within post-communist Czech or Slovak society, citing a continued or growing preference for non-party politics (more than a third of Slovak, and three-quarters of Czech mayors are independents):

the mayors of rural municipalities (including villages and towns) represent in their experiences and their approaches the great hope for the emergence of a political force operating on a basis other than the party principle. The trend of recruiting local councils from political independents is a particularly hopeful one. Engaged mayors are beginning to sense that they can be the initiators of a political culture of a completely new style.

(Blažek ‘Obnova venkova’).

Starting hypotheses: positive and negative potential of OF and VPN

It is hypothesised that OF and VPN had a unique potential (in comparision with other, more conventional political actors of the time) to become vehicles for community-based civic renewal founded on a convincing narrativisation of a community's collective experience, trajectory or destiny. If they could win support for, and successfully manage, institutional transformation at the local level, this would also induce positive feedbacks in terms of a re-stocking of social and cultural capital. The outcome would be a self-confident, self-regulating, well-integrated social organism. This would represent a vital contribution to the process of democratisation, adopting the functional definition of the term used by Frič and Strečenská (1992) ‘as an increase in the influence of civil society on the course of social life’. On the other hand this positive potential must be balanced by recognition of plausible negative scenarios according to which local OF- or VPN-inspired collective actions could be effectively captured by partial interest groups, could be rejected by conservative social milieux struggling to cope with the demands of rapid social change, or could be unwittingly implicated in a disorganisation of local community life by failing to articulate with existing collective actors and identities.

The fulfilment of positive or negative scenarios hinged to a large extent on the functioning of local fora as social movement networks. A study by Buštíková conceives the potential of local OF in terms of facilitating a ‘loosening’ or ‘opening up’ of social networks, thus enabling broader participation in the public life of a community, followed by a later ‘resetting’ or reconfiguration as new patterns of community life, discourse, social control and governance became re-institutionalised (1999: 23). OF and VPN would thus have been the vehicles for a participative adaptation to a new mode of regulation. Conversely, where the negative scenario was fulfilled, this may be because fora served not as bridges between local actors but as gatekeepers or filters, enabling only a small clique to profit from the opportunities that the social transformation brought with it, and blocking (or at least not stimulating) participative adaptation for the majority of members of a community.

OF and VPN as social movements

In understanding the emergence and spread of OF and VPN as social movements, resource mobilisation theory provides a useful perspective. According to Lustiger-Thaler and Maheu:

Resource mobilisation theory … argues that constraints, inequalities and levels of domination cannot in and of themselves explain collective action and its impact on political systems. Collective action has to do with access to resources… .The social and political impact of grassroots groups, and their claims upon the larger polity, are mediated by their organisational aptitudes.

(1995: 162)

Clearly, OF and VPN were social movements which responded to a unique opening of the opportunity structure for collective action following the collapse of the communist system, and to this extent were phenomena determined by the availability of physical and ideological resources external to the lives of local communities. To put it another way, they were the product of a change in the ‘how’ rather than the ‘why’ of collective action. Access to external resources — above all the possibility of integration into the organisational structure of a powerful social movement network — provided the opportunity to articulate local claims, empower local self-help initiatives, or facilitate the ambitions of local social elites. In understanding which option was taken, however, we have to inquire after the identity or the social conflict to which the collective action gave expression, and the way in which this was articulated by the community concerned. Mobilisation around a reflexively formulated project for social change or community development amounted to the appropriation of external resources by local actors (the re-insertion of a ‘why’ of collective action). On the other hand, failure to reflect underlying social problems or to develop self-reflexive identities in interaction with a particular social constituency was likely to render social movements hostage to capture for the partial interests of pre-existing social elites.

Another perspective on social movements holds that they supplement the functioning of political systems which are necessarily imperfect at representing social interests, needs and identities (Offe 1987). New social movement theories developed to explain the coexistence between relatively stable political systems and anti-systemic collective actions whose effect is in part to directly satisfy needs the system fails to meet, and in part to push back the boundaries of representative procedures in order to admit identities and discourses previously not accorded legitimate status. This usually produces a tension within movements themselves between self-institutionalising and anti-systemic moments, such that they challenge the legitimacy of a political system and simultaneously contribute to state building (Lustiger-Thaler and Maheu 1995: 163–9). As actors which were anti-systemic in relation to a system which capitulated almost before they had emerged, OF and VPN were genetically associated with the statebuilding project which superseded this. Nonetheless they posed difficult questions with regard to the reintegration of public space, in particular articulating claims to citizenship and participation which tested the inclusiveness of the new Czechoslovak state.

Such a conception is implicit in the vision set out by VPN's founder-leader Fedor Gál at the beginning of 1990. In his view VPN and OF would — once their ‘revolutionary’ role had been completed with free elections — contribute to the further democratisation of Czechoslovak society in three distinct ways: as a loose political club purveying a non-political politics based on dialogue and stripped of the hierarchies and rituals of traditional political organisation; as the seedbed for economically independent institutions in areas such as research, the media and publishing; and (most importantly from the present perspective) by stimulating the emergence of problem-oriented movements which would both ensure the societal control of power and facilitate various forms of civic self-help, thus increasing the independence of civil society and its rapid mobilisability in the event that democracy were again threatened (‘Vízia našej cesty’, verejnost’ no. 5,16 January 1990). Gál's vision not only presupposes that the emerging political system would under-represent the spectrum of more or less localised social constituencies; it also presupposes sufficiently developed local civic cultures to experience and express this representational deficit and be capable of exploring forms of self-representation and self-regulation beyond the boundaries of formal institutions. OF and VPN thus promoted highly demanding patterns of local civic life, which were not everywhere accepted, possibly because populations expected the political incarnation of the movement to meet their needs without remainder.1

Inquiry into the longevity of a particular local OF/VPN organisation, and into its following either the ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ developmental trajectory sketched above, therefore leads to questions about the human potential with which different communities faced up to post-communist transformation, meaning the level of development of local civic cultures in terms of their structuration, integration, self-image and the competences of individual and group actors within them. As these are variables partially predetermined by settlements' demographic, socio-economic and geographical attributes, it was possible to test some of these relationships by an appropriate selection of case studies. The Czech cases encompass small towns and villages of different sizes, different degrees of proximity or peripherality in relation to Prague, different types of social structure and different functions within the settlement structure (including for instance agricultural communities and dormitory towns). However most are basically rural communities. The single Slovak example, Humenné, as well as providing a complementary urban example, is a useful test case in other respects. According to Falt’an et al. (1995), the Zemplín region suffers from ‘historical marginality’, given its geographical peripherality, a tradition of out-migration for work and its belated, primitive industrialisation. In common with large parts of Slovakia its development was more marked than most Czech regions by directive urbanisation and industrialisation projects after the Second World War that concentrated settlement and economic activity into growth poles — regional and district capitals or sites for greenfield industrial investments. This was when Humenné, hitherto a service and processing centre in an agricultural region, acquired a large industrial (textile, engineering, construction and especially chemical) capacity: growth was concentrated in the period 1960–80, when population more than doubled to 26,000, primarily in association with the establishment and expansion of the chemical plant Chemlon, which at one period had 6,000 employees. During the later years of state socialism many Czech towns began to acquire a more diversified economic structure, in particular a more developed tertiary sector (Musil 2001: 288), but the growth of Slovak towns such as Humenné continued to be a product of industrialisation, often leading to over-dependence on single enterprises, which substituted municipal social services (thus weakening the last vestiges of self-government) but could not make up for a generally impoverished civic infrastructure caused by the dominance of economic considerations in settlement planning. These were not promising preconditions for a self-regulative adaptation to post-communist conditions. However the study seeks to investigate, among other things, whether a more variegated distribution of human potential is visible at the sub-district level, and whether this was reflected in the impact of VPN on civic culture.

Self-government and extensive local autonomy

Merely by virtue of their presence in many if not most local communities during the critical first year or so after the ‘velvet revolution’, OF and VPN were in a pivotal position to coordinate the process of reintegrating the intricate network of public spaces which would make up the ‘new’ nation-state. Early pronouncements acknowledged this role and stressed that the process must take place from the bottom up, beginning with action on the local level, within the context of each municipality (obec). For Civic Forum:

Politics begins in communities [municipalities] whose members feel sufficient co-belonging that it is worth their while complying with democratic procedures…. Along with economic reform we must come up with, for example, new territorial arrangements in which it will be abundantly clear where the sphere of citizens' self-government ends and the competences of the authorities begin…. The state has to be built organically, gradually … through the expansion of our homes and our communities… . [W]hat we lack most of all today is community, and without living, self-governing communities politics and democracy are mere figments.

(Fórum no. 7,1990, supplement: 3)

Public Against Violence championed an identical project in opposition to hitherto dominant centralising forces:

The alternative is decentralisation, self-government in every region … the division of the res-publica into thousands of individual publics, making competent decisions about their own environments…. That is why VPN supports the emergence of the most varied fora… . These fora, and particularly those at the local level, can become the source of a genuinely cultured local or regional milieu, the activisers of local life, local administration, local culture in the broadest sense of the term.

(‘Predstava o krajine’, verejnost' no. 9,1990)

The meta-narrative of transformation to which these documents subscribe is one of the liberation of human potential suppressed by the centralistic administrative modes of governance which characterised the communist system, optimistically envisaging the spontaneous reconstruction of society from the bottom up, predicated only on the removal of institutional barriers to community self-regulation. High hopes were invested in formal local self-government structures, but the wider goal was to re-establish local communities as self-determining organisms in a more profound sense. Buček's distinction between ‘local self-government autonomy’ and ‘extensive local autonomy’ is useful here:

[Extensive local autonomy] ‘is not guaranteed constitutionally or legislatively [but] belongs to the non-political, informal sphere… . It reflects the aggregated efforts of a locality, of all local actors to attain the locality's collective aims, to control its social reproduction (through cooperative action and participation) and to resist unwanted external interference.

(Buček 2001: 166–7)

One might equally cite Vašečka's definition of local community in Chapter 9, stressing the complexity of the network of actors, relations and mutual obligations which needs to be managed, usually coordinated by, but never reducible to the actions of local self-government.

The introduction of new institutional solutions (such as the devolution of competences on to freely elected local governments or the establishment of political party structures) was a necessary but insufficient condition for the revitalisation of human potential. The wider need was for local facilitators to find ways of mobilising that potential, set up spaces for a public dialogue where the ‘locality's collective aims’ could be worked out and recruit community leaders. ‘Self-government’ (the term samospráva is used in Czech and Slovak for what would normally be called ‘local government’ or ‘local authority’ in the UK) was viewed unequivocally as an institution belonging to civil society in OF and VPN programmes, which envisaged a creative synergy between its organs and voluntary social organisations, churches and family circles, as communitarian traditions were reinvigorated. The ideal outcome would be to enhance a community's self-regulating capacities, bolster social cohesion and natural mechanisms of social control, and reduce dependence on external actors and institutions.

Sources

The main sources for the following case studies comprise in-depth interviews undertaken by the author in 2001 with several former mayors, functionaries and activists in each country. Claims to representativeness are largely sacrificed in favour of reconstructing in some detail the lifeworlds of a small number of distinct communities. In Slovakia a single, in-depth case study is presented to illustrate many of the challenges which faced a district VPN organisation in a medium-sized town, where the contestation between the two alternative trajectories described above became personified in a power struggle between two social networks within the organisation. This evidence is augmented by notes from interviews with VPN activists from other parts of Slovakia and at the central level. The selection of Czech interviewees was based on a sample of written first-hand testimonies taken from the Norwegian-sponsored project ‘Learning Democracy’,2 and interviews were supplemented by documents supplied by interviewees.3 Five mainly rural municipalities are compared in terms of the ability of local OF groups to initiate positive changes and their vulnerability to ‘negative scenarios’.

Public Against Violence (Humenné)

Foundation and early development of Humenné VPN

As in most larger Czech and Slovak towns, the people of Humenné (population nearly 37,000) responded relatively quickly to the events of 17 November 1989 in Prague by staging demonstrations and meetings and by setting up strike committees in their workplaces following the calling of a symbolic two-hour general strike for midday on 27 November. High school students were especially active, inspired by the leading role played by student representatives in Prague and elesewhere. In the first days of the revolution, as television, radio and most newspapers were still propagating the Communist Party or government version of events, any information from or about emerging opposition groups was vital if support was to grow outside the main urban centres and in peripheral regions such as Zemplín. As was often the case in eastern Slovakia, communications with Prague were better than with Bratislava, and activists in Humenné initially obtained more information about Civic Forum than about VPN, thanks in part to literature fetched by two guards working on the Prague train line (interview with Korba, Ďugoš and Miško). Indeed until mid-December as many OF as VPN groups were being formed, and the town's coordinating committee bore both names. Visits from OF activists (mostly students and actors) from Prague and Košice were received in Humenné before Bratislava VPN representatives came to the town.

Most of the members of the first coordinating committees represented workplace groups or interest groups (such as religious communities) rather than territorial units such as neighbourhoods and municipalities. The first specifically local demands concerned environmental and religious issues, which were issues of existential importance in a district with a sizeable chemical industry and an ethnically and confessionally mixed population (with large Ruthenian and Ukrainian minorities, which form the cores of Greek Catholic and Orthodox congregations). An early conception of the structure of the district VPN devolved to local groups the prerogative to add their own demands to that of the Humenné coordinating committee, whose programme would automatically be modified if a petition with at least twenty signatures was received (minutes of coordinating committee meeting, 12 January 1990). Demands addressed to the administrative authorities were thereby aggregated from the bottom up, so that even very specific local problems would not be overlooked. Later in 1990 other issues emerged as natural foci for mobilisation — notably property restitution and the transformation of agricultural cooperatives — partially eclipsing ecological and religious issues, but providing VPN with a continued strong raison d’etre.

At the start Humenné OF/VPN had sought access to the media to address the local community. Communications were an obvious concern, to combat the real risk of isolation from local society, and early meetings record repeated urgings to get the message out ‘among the people’ or ‘into the factories and schools’. A newsletter was founded (the first issue came out on 4 December) and a suggestions box was provided where people could indicate their own priorities or pass on ideas. The discourse adopted by Humenné VPN — informed by a mix of optimism and cautious un-certainity about the limits of the revolution — was one of partnership, reciprocity and the need to reintegrate a community artificially divided by interests generated by the redundant system. From the outset there was a clear intent to apply the human potential of a loose civic opposition to the solution of community problems: thus the first ‘action committee’, elected on 29 November, delegated portfolios for legal matters, health, transport, the Catholic community and propagation, a division which probably reflected the expertise of volunteers rather than any overt priorities. By mid-January, when a proper structure began to take shape, in keeping with the newly approved statutes of VPN as a nationwide organisation (with separate district and town committees to match the hierarchy of the administrative authorities), thirteen committees or expert groups had been established covering all important areas of local community life.

Early statements demanded the reclamation of the public space of the town and attempted to redefine the dominant discourse within public life. Top of a list of demands issued on 3 December was one for the removal of all banners and slogans proclaiming the leading role of the Communist Party. By 19 December, following wider public soundings, a more detailed and ambitious list of demands had been formulated, many of which proposed a reintegration of the urban community based around an informed citizenry, culturally literate and historically aware. Streets should be renamed, monuments restored and repositioned, the museum collection reconceived so as to reflect ‘truthfully and objectively’ the history of the town and district. The recently closed summer cinema should be reopened and other underused cultural facilities revived with a full programme of events and activities. A commission consisting of experts and representatives of the local SZOPK4 branch should be set up to produce an accurate report on the state of the environment and the health implications for local people. (This followed the revelation, publicised in the first OF/VPN Humenné newsletter, that the local environmental monitoring station did not actually possess the instruments needed to carry out pollution measurements because of a lack of funding, and had hitherto relied on information supplied by the polluting enterprises themselves!) There was also the thorny question of the imposing Communist Party building, the future use of which, it was suggested, should be determined on the basis of a broad public debate. One interesting initiative was the idea (subsequently brought to fruition) for the establishment of an Andy Warhol museum in his ancestral town of Medzilaborce, mentioned on 19 December, and symbolic of a different kind of reintegration — the reintegration of the region with modern world culture.

The empowerment of citizens also comes through in demands related to the activities of the local administrative authorities. Councillors were pressed to defend their record in front of their constituents, and, if requested, to resign; public ‘control commissions’ were seen as means by which (following the co-optation of opposition representatives) notoriously corrupt practices such as the allocation of flats and garages and the granting of building permits could be cleaned up, and injustices redressed. There was a recognition that people's support for democratic transformation would hinge on their own experiences (whether their complaints were satisfactorily addressed, whether they were able to secure justice for past wrongs). The VPN coordinating committee, as the self-proclaimed mouthpiece for the ‘broad public’ or ‘the workers and students’ of Humenné, demanded access to all the meetings of city and district national committees and later agitated for the replacement of a proportion of councillors and officials by its own delegates and those of other social organisations and political parties. Yet in late January 1990 minutes of VPN meetings still record a debate about the proper terms of involvement in local administration: Korba referred to cautionary advice from Bratislava that delegating too many VPN candidates could result in their acceptance of co-responsibility for problems they had not caused and were powerless or unqualified to redress. The suggestion was made to give priority to experts, even if they were not VPN supporters, when putting forward candidates for public office. This advice was later heeded when VPN nominated Matej Polák, an agricultural engineer from Košice and an ex-communist, as the new head of the district national committee in February 1990, a seemingly logical choice in an agricultural district, but a decision later regretted — his short term of office was characterised by the first suspicions of clientelistic privatisations, in which certain VPN representatives, as well as managers of leading local enterprises, were implicated.5

Both the district and city national committees underwent quite wholesale reconstruction, leaving the Communist Party with just 25 per cent of seats in the latter, with VPN making the largest number of new co-optations, alongside representatives of the newly formed Christian Democrats, Greens and Democratic Party, the reformed Social Democrats and the ‘old’ Freedom Party. The VPN representative Zuzana Dzivjáková became the new chair of the city national committee (commonly referred to as the mayor or ‘primátor’). VPN nominated its best candidates to the city national committee, which was regarded as more important for two reasons: its competences included housing and property, matters over which the greatest disputes arose in Humenné during 1990; and from the beginning of the year the tone of political debate indicated a concerted movement for decentralisation and strong self-government, in which municipalities would be the key actors, whereas many voices questioned the necessity of maintaining both district and regional administrative organs.

Internal problems of the district organisation: contestation of the movement's identity

The first three months saw a considerable turnover in the local VPN leadership, and the effective displacement of many of the founding members by a rival group with its roots in the district committee of the Socialist Youth Union (SZM). Of twenty-nine members of the first proper coordinating committee elected on 12 January 1990, seven were expelled on 14 February and a further eleven were no longer committee members (loss of commitment was common when people started businesses or made radical career changes) — a turnover of more than 60 per cent in a month. One of the grounds given for the expulsions was that those people ‘did not represent anyone’ (meaning an enterprise or organisation). The subsequent struggle for the identity of the movement negatively affected VPN's public image in Humenné: though such problems were typical in many localities (and also afflicted OF), Humenné is referred to in several VPN documents (along with a handful of other districts) as a ‘problem case’. With central mediation the dispute was resolved in favour of the original founders in October 1990, resulting in a second wholesale replacement of the district VPN leadership (of the eighteen members of the district coordinating committee who signed the motion to expel the ‘original’ founders only two remained in the reformed district council on 14 March 1991). However this came too late to save VPN from a rather disappointing performance in the local elections.

The internal struggle had soon begun to manifest itself in a breakdown of communication and trust between members of the district coordinating committee and VPN representatives on the reformed national committees. This may have reflected the disconnection between the two sets of institutions: of the first twenty-one VPN delegates to the city national committee, there were only three current and one former member of city or district coordinating committees. In contrast to the situation which was common in villages, where OF or VPN often ‘institutionalised’ themselves in the local self-government structures, and the movement (as a separate structure) became less relevant, a town the size of Humenné saw the development of a duality within the movement, which was intended to avoid the accumulation of functions by a narrow leadership, but which, in the worst case scenario, could lead to mutual isolation and rivalry. In Humenné the problem was more serious than poor coordination: VPN structures, it is alleged, actually hindered attempts by mayor Dzivjáková, in particular, to push through personnel changes in municipal institutions or investigate a Kčs 826,000 fraud at the cultural centre (Jozef Balica, member of the commission of the VPN district council: pre-local election literature, November 1990), and generally impeded reforming initiatives on the part of VPN delegates in public office, because they had begun to constitute a vested interest with close links to the former communist local elite. A report produced by the central control commission of VPN later concluded that, as a result of the lack of support for its public representatives by Humenné VPN, ‘The process of taking over the state administration is paralysed — if this was the intention, it has worked perfectly’ (‘Zpráva o situácii VPN v okrese Humenné’ ÚKK, KC VPN, 15/10/90).

VPN Humenné had achieved some initial success in pushing through the personnel changes it sought in the state administration — besides the national committees, VPN-approved figures took over at the head of the school board and the tax office. But ‘old structures’ showed much greater resilience in economic enterprises and the lower tier of public services, and the lack of change in the management of factories, farms or schools began to have a disheartening effect on their employees. Theoretically the matter lay in the hands of workforces themselves — they had the right, either through VPN cells or independently, to voice their disapproval of the incumbent management and force the holding of a new selection process (in effect a workforce election) for leading posts. But in the absence of any formal procedures to guide the process, reliant only on the moral compulsions of all sides, and in a situation of power asymmetry, managements were frequently able to win the overt approval of the majority of employees or ward off the holding of an election, giving themselves sufficient breathing space to ‘capitalise’ their position in the form of various types of more or less transparent privatisation scheme. VPN itself had to combat residual paternalistic expectations among employees, which were strongest in the district's outlying villages among employees of agricultural cooperatives. Letters poured into the district headquarters from workers pleading with what they saw as the new power centre to come and ‘restore order’ in their village. VPN Humenné continued to devote considerable time and energy to organising visits to the villages (each member of the coordinating committee was given responsibility for five or six), which had the character of public education exercises, explaining to villagers their rights or suggesting procedures for influencing the management and personnel policy of the organisations in which they lived and worked. To begin with the main value of these activities was simply in enabling people to express grievances and to obtain sympathy and encouragement, because ‘people needed to tell their story’ (interview with Korba); later in 1990, advice on restitution and cooperative transformation had a more practical purpose, since a high proportion of families in the Humenné district had claims to smallholdings confiscated during collectivisation. Legal counselling proved to be one of the most empowering actions VPN could take, and weekly legal advice shops held all over the district were well attended.

The call by the VPN national coordinating committee in April 1990 to disband enterprise VPNs and build the structure of the movement exclusively on a territorial hierarchy matching the administrative division of Slovakia was met with disappointment in Humenné, as the workplace was a natural space for collective action in a city of large industrial enterprises and public corporations. It coincided with an increasing unwillingness of people to engage in public affairs. Dzivjáková draws a direct relationship between these developments, based on the communications received by VPN from the public:

In the beginning people spoke out openly, and were not afraid to point directly at the particular official or boss whom their complaint concerned. The decision to finish with VPN in enterprises was an unfortunate one, at least in Humenné, as we thereby opened the way for the return of the old structures.

(Interview)

In August the VPN Humenné district committee issued an appeal for the re-establishment of VPN cells in workplaces, including cooperative farms, utilising the new law on trade unions, accompanied by a prescient warning to workers to monitor the establishment of new share companies by the managers of state enterprises and note any connections between new private firms and the economic nomenclature. The appeal also pointed to alleged cases of discrimination and intimidation by ‘unreconstructed’ managements against VPN activists, disguised as organisational changes in accordance with the Labour Code (OKV VPN Humenné, ‘Výzva’, 13 August 1990). It won support from a few other district organisations, but was ignored by Bratislava. It expressed a feeling widespread in some peripheral regions, where communist control had often been firmer (melded to an earlier system of informal social control based on the power of extended family clans), that VPN had acted too hastily and too magnanimously: that rooting out deeply ingrained clientelist relations would for some time yet require organised collective action backed by political clout; and that it was precisely within firms on the verge of privatisation that the most was at stake and there was the greatest need for organised resistance to the regrouping of ‘old structures’.

Such was the situation at the District Industrial Enterprise (OPP) in Humenné in November 1990, according to the VPN coordinating committee there (which had not been disbanded):

Rumour has it that [the director] and a narrow circle of his people are up to something, but the work collective is not in the picture and everyone's waiting to see what trick these rogues come up with to get something for themselves at the expense of the collective as a whole. In any case our knowledge of their capabilities can only serve as a warning. Therefore we cannot be inattentive, and we feel a responsibility to point things out and act. So we are trying to analyse the situation in the firm and present suggestions for a way forward.

(Letter dated 6 November 1990)

The quotation is from a letter addressed to both the Interior Minister and the VPN coordinating committee in Bratislava,

without [whose] assistance in these circumstances it will not be possible to redress the situation… . These people have already developed firm structures and are better organised than in the past… . They have the necessary resources, experience, unity of purpose, finance and influence. The influence which they should no longer have — which we should have.

(Letter dated 6 November 1990).

Detailed examples are given of how repeated promises of personnel changes had not been carried out, how votes of confidence and re-selection processes had been manipulated, and how, through a combination of bribes, coercion and benevolence towards petty theft, the top management had been able to forestall or curtail initiatives by the various collective bodies which began to, or had the potential to, threaten its control of the firm — the union organisation, the works council, the supervisory board and VPN.

Recourse to a personal appeal to the Interior Minister is interpretable as a residual paternalism or protectionism on the part of the work collective, but it also constituted a legitimate reproach against the perceived toothlessness and belatedness of legislative measures designed to enable the replacement of top personnel in enterprises: the government did not issue guidelines on this until 12 March 1990, and this did not amount to a clear set of procedures, only obliging managers to agree to workers' demands to hold ‘round table’ discussions, without addressing the fundamental power asymmetry between the parties, manifest most critically as a disparity in the social capital mobilisable by managerial networks on the one hand and ordinary workers on the other.6 In OPP a round table took place under the supervision of the chairman of the district national committee, Matej Polák, who, it turned out, had close ties with the company director, having previously collaborated in establishing foreign trade relations for the firm, and stood to profit from the latter's plans to privatise the wood-processing facility in Snina. Polák was nevertheless a VPN appointee, and the district coordinating committee (until its replacement in November 1990) stood by him, and so came into conflict with the OPP VPN branch, which openly criticised Polák's part in preventing management personnel changes. VPN district representatives in turn questioned the representativeness of the enterprise VPN structure, ironically only shortly after they had issued their appeal to refound VPN in enterprises. The nature of the internal conflict is indicated by an earlier letter to the VPN district council:

You were indifferent to all of this and we believe that several of your functionaries were acting on their own interests. How else can we explain the fact that on 13.8.90 you issued an Appeal with ten demands geared towards the intensification of our activities in workplaces. But when we organised an enterprise-wide dialogue on 10.10.90 … your secretary Mr Hladík visited us that morning and warned us not to organise anything because you had just issued an appeal for the withdrawal of all activities from workplaces… . During this whole affair you took no interest in our work until there were fears that this workers' meeting could result in demands for radical corrective measures in the firm.

(Letter dated 26 October 1990)

This episode illustrates the penetration of an interest-based politics into a movement initially disavowing this type of politics, and the centrality of personnel issues as a touchstone for competing transformation strategies. The OPP VPN group was appealing to the principle of self-regulation — that all collectives and organisations should have the right to choose the directors or managers they considered to be the best qualified and morally most suitable.

The recapture of the Humenné district and city organisations by the ‘founders’ represented the restoration of such a discourse, and the first opportunity to demonstrate this shift was in the run-up to the municipal elections of November 1990, when the goal of a strong, self-sufficient local council was defended, meaning both decentralisaton of competences and finance from central government, and liberation from dependence on the power of large enterprises which had previously subsidised much of the social and recreational provision in towns like Humenné and, through elite networks, effectively controlled local administrative decision-making. The compilation of the election programme, and indeed the list of VPN candidates, was turned into an exercise in participative ‘projecting’ and recruitment: policy suggestions were solicited and people were urged to ‘help us find wise, enterprising [candidates] who enjoy general respect’. The programme appealed to common effort and sacrifice, and became an exercise in self-criticism, acknowledging a struggle against a dependency culture which afflicted everyone:

Subconsciously we thought that … from the centre will come instructions on how to make changes in the villages, towns, districts and regions. We did not reflect on the fact that the revolution also meant abolition of any kind of centralism. Freedom and democracy have arrived, and we will have to deal with problems ourselves.

(J. Balica, pre-local election literature, November 1990)

To the extent that the dispute between the two groups within VPN Humenné was over principles, a distinction can be drawn between alternative conceptions of legitimacy: whereas the ‘original’ founders saw themselves as informal public representatives, whose legitimacy depended entirely on the work they carried out in the community and the support this engendered, the ‘SZM group’ viewed legitimacy as something delegated by specific organisations or firms. The ‘original founders’ in Humenné also adhered to an increasingly radical discourse which regarded any compromise with ‘old structures’ as unacceptable and dangerous, introducing a new stricture into the statutes (against the recommendations of Bratislava) that no ex-communists could hold office within VPN. The communist elite was viewed as so wedded to a nomenclature politics of patronage as to be morally unsuitable for office-holding in any non-corrupt regime, at least until they (as individuals) had demonstrated their goodwill by participating in the democratisation process as ordinary citizens or rank-and-file VPN members.

As noted, the capture of VPN Humenné was only reversed when order was effectively restored from above in the movement's hierarchy. Although this took place according to procedures contained in its statutes, it somewhat contradicts the decentralising ethos of VPN: Fedor Gál, VPN chairman in 1990, says the national coordinating committee intervened in the affairs of local branches very reluctantly, and regarded each such intervention as a failure of sorts (interview). In this respect developments in Humenné illustrate a wider problem within the life of the movement. Peter Zajac, another VPN founder, describes the position of the coordinating committee as like being between Scylla and Charybdis: VPN was expected to resolve psychological and social problems, ‘install order’ in an organisation or locality, arbitrate trivial personality clashes, and so on. On the other hand it found itself exposed to accusations in the press and sometimes from within its own structure of being the bearer of a new totalitarianism, of secretive ‘cabinet-style’ decision-making and of a lack of internal democracy (interview). According to Gál, local organisations looked to Bratislava with a mixture of aversion and helplessness (interview). Another member of the central leadership, Daniel Brezina, believes with hindsight that many of VPN's public activities were poorly conceived, not fully appreciating the priority of generating self-regulative capacities within communities. Thus legal advice shops, for example, were often too specific and encouraged continued dependency by placing VPN in the position of distributing justice or issuing instructions; instead they should have remained more on the level of general civic education about how democracy and the market work (interview).

In practice it was politically impossible to ignore the overwhelming public cry for help to which both OF and VPN were exposed: in the first three weeks or so of its existence VPN received more than 15,000 letters from the public at its Bratislava headquarters alone, many of them requests for help or poignant accounts of wrongs perpetrated on people and their families during the communist regime. Many rank-and-file communists also turned to VPN to help resolve the crisis of conscience or identity they were undergoing (verejnost' no. 3, 22 December 1989: 4–5). Given the utopian expectations which the velvet revolution aroused, OF and VPN, as its most prominent symbols, were in a sense condemned to try to ‘install order’ and ‘distribute justice’ if they were to maintain popular belief in the (inevitably painful) transformation of society.

Reintegration of public space: VPN's legacy in Humenné

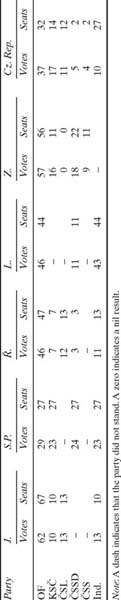

The history of VPN Humenné illustrates the vulnerability of organisations to capture in a weak civic culture. The cooptation of many of the leading lights in February and March 1990 on to the city and district councils, together with the high turnover of volunteers within the coordinating committee, led to the weakening of natural control mechanisms both from the ‘intellectual elite’ of the movement (preoccupied with municipal affairs) and from the rank-and-file (inexperienced in self-organisation). There was no formal district assembly between February and October, and yet a small clique around the former SZM leadership was able to bypass democratic procedures to take control of the district organisation, excluding many of the founding members without eliciting any protests among a sizeable membership. However the feud led to a loss of legitimacy for VPN within Humenné. A coalition for the local elections between VPN and the Christian Democrats (KDH), which led to success in many parts of Slovakia, fell apart in Humenné and Dzivjáková was narrowly defeated by the KDH candidate for mayor (nominally standing as an independent), with VPN finishing only third in terms of council seats behind KDH and the communists (winning seven out of thirty-nine). In the district as a whole VPN was only able to field mayoral candidates in forty-three out of 108 municipalities, and twenty-three of these were coalition candidates. Although the result in Humenné was only marginally below the national average for VPN of 20 per cent of council seats, this average is deflated by the non-existence of the movement in many small parishes.7 Humenné stood out as a disappointing return among larger towns, along with Martin and Senica, where the local organisations had also failed to find a coalition partner and had similar ‘problems with themselves’ (Telefax no. 28, 1990). Paradoxically one of VPN's best results in the district was in Snina, where it won 32 per cent of seats in the 1990–4 council chamber despite the organisation having a miniscule membership there (see Tables 3.1–3.4 for a summary of local election results).

Following the split in VPN in 1991, few members or branches in the Humenné district transferred their allegiance to Vladimír Meciar's Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), which continues to have relatively little support in the town itself (where the vast majority of VPN organisations were), holding just four out of thirty-nine seats on the last town council. The district HZDS organisation was formed in Snina, where it remains electorally strong. Among its founders were members of the ousted Humenné district VPN leadership, who evidently saw in HZDS an organisation better able to advance their political or business careers.

Minutes even of early VPN meetings suggest a problem finding suitable representatives in both Snina and Medzilaborce, the district's second and

Table 3.1 1990 local election results in main towns in Humenné district (percentage of councillors)

| Party | Humenné | Medzilaborce | Snina | Slovakia |

| VPN | 18 | 25 | 32 | 20 |

| KDH | 36 | 0 | 36 | 27 |

| KSS | 23 | 69* | 16 | 14 |

| DS | 8 | 6 | 16 | 2 |

| SDSS | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ind. | 3* | 0 | 0* | 16 |

Note: * Political affiliation of mayor.A zero indicates a nil result.

Table 3.2 1994 local election results in main towns in Humenné district (percentage of councillors)

| Party | Humenné | Medzilaborce | Snina | Slovakia |

| HZDSa | 28 | 35 | 37 | 23 |

| DÚa | 8 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| KDH | 21b | 0 | 33 | 20 |

| SDL | 23 | 53bc | 13 | 16 |

| DS | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| SDSS | 5 | 0 | 0 | – |

| ind. | 10 | 0 | 3bc | 9 |

| Note: | aVPN successor parties |

| bPolitical affiliation of mayor | |

| cSame mayor re-elected. |

Table 3.3 Mayors by party in Humenné district in 1990 (percentage of municipalities)

| Party | Okres Humenné | Slovakia |

| VPN | 18 | 17 |

| KDH | 24 | 19 |

| KSS | 23 | 23 |

| DS | 0 | 1 |

| SDSS | 0 | 0 |

| ind. | 20 | 25 |

| No candidate | 13 | 3 |

Table 3.4 Mayors by party in Humenné district 1994 (percentage of municipalities)

| Party | Humenné | Slovakia (excl. no cand.) |

| HZDS* | 22 | 13 |

| DÚ* | 0 | 2 |

| KDH | 24 | 15 |

| SDL | 24 | 18 |

| DS | 0 | 2 |

| SDSS | 0 | 0 |

| ind. | 20 | 29 |

| No candidate | 1 | – |

Note: * VPN successor parties

Key to parties (Tables 3.1–3.4):

VPN Public Against Violence

KDH Christian Democratic Movement

KSS Communist Party

DS Democratic Party

SDSS Social Democratic Party

HZDS Movement for a Democratic Slovakia

DÚ Democratic Union

SDL Party of the Democratic Left (transformed Communist Party).

third towns. Whereas in Snina this enabled the capture of VPN by partial interests who then declared for Meciar's HZDS, Medzilaborce presents a more complicated picture. The foundation of the VPN town coordinating committee in early 1990 was allegedly conceived directly as a means to defend the position of communist functionaries on the national committee. The VPN chairman, a Mr Petruš, was said to consult regularly with the old communist elite which thereby continued to exercise power from the shadows of public life, according to a statement by the participants in a meeting to refound VPN Medzilaborce addressed to the district coordinating committee (6 February 1991), who stressed their own credentials as the ‘original’ (later sidelined) founders of VPN in the town. The struggle for control of VPN did not, however, lead to a permanent schism in public life in Medzilaborce, perhaps because the town is, and the organisation was, much smaller, and because community life is also consolidated by the town's role as the centre of Ruthenian culture. In Medzilaborce (where Ruthenians make up 40 per cent of the population) a unity of purpose transcending party affiliations is therefore more easily maintained.8

The vast majority of Humenné district VPN groups, meanwhile, had regrouped behind the ‘founding’ wing of the movement. In January 1991, there were 589 registered members of seventy-eight local VPN clubs in Humenné district, of which 415 members in fifty-one clubs were in the town itself (in Snina there was just one club with eight members, plus two more clubs with fifteen members in the surrounding countryside). Given that ODÚ (Civic Democratic Union)–VPN still had as many as 550 members in the district late in 1991, it would appear that most VPN activists had crossed smoothly into the ‘centre-right’ successor party. It is perhaps surprising to note that the transition to a political party had not produced a step demobilisation of local activity (as was the case following the split of OF), although anecdotal evidence suggests that during 1990, before VPN kept accurate membership lists, activity had been much greater in the countryside (according to Korba, small cells of five or ten people existed in almost every municipality in early 1990) but had gradually reduced until a core of committed activists remained, almost exclusively in Humenné itself.9 The organisation remained active right up to the formal dissolution of ODÚ–VPN.

A long-term legacy is also apparent. A section of the current political scene in Humenné can trace its origins back to VPN, which initially coexisted very closely with the local Christian and Social Democrats as well as the Democratic Party (interview with Korba). Workplace VPN groups often made the transition to trade union organisations, and one former member of the VPN district council, Jozef Balica, is today a member of the Presidium of the steelworkers' union OZ KOVO. Some former VPN members also continue to engage in civic initiatives, including SKOI (the Permanent Conference of the Civic Institute), which is probably the most direct inheritor of the VPN legacy in Slovakia. SKOI was established in September 1993,

fifteen months after the elections which determined that the new Slovak government would not continue in the radical democratic politics of the Slovak and Czech governments of the post-revolutionary era … [in order to] continue to protect, cultivate, ennoble and popularise the ideals of November 1989.

(Undated SKOI leaflet)

Its main activities consist of organising discussion fora (known as clubs) in over fifty towns, targeted public information campaigns (recent campaigns were on public administration reform and on NATO membership) which typically take the message into provincial and rural Slovakia through student and other volunteers, and expert working groups intended to contribute towards regional and national development projects. Similar public educational and informative campaigns are carried out in the region by a group which bears the name Prešov Civic Forum (POF), whose second branch is in Humenné.

Both are examples of a strong wing of the Slovak NGO movement involved in the defence of human rights, the promotion of civil society or environmental issues (Woleková et al. 2000: 20–1). During the last Meciar government such NGOs10 were instrumental in uniting the whole sector as a political force, establishing the Gremium [Panel] of the Third Sector (G3S) to present common standpoints and coordinate activity, and to act as a service organisation. A major role was played by former VPN activists such as Pavol Demeš and Helena Woleková — intellectual activists who withdrew from parliamentary politics following the defeat of the original post-revolutionary transformation programme at the 1992 elections, and instead attempted to build democracy ‘from below’. In many instances such NGOs have also been catalysts for building partnerships with public and private sector actors, which have often performed similar functions in relation to community empowerment as the Czech Countryside Renewal programme (see below, pp. 72–3).11 It is symptomatic of the distinctive post-communist political development of Slovakia that NGOs have played a leading role in initiatives for extensive local autonomy. Local councils were initially more reticent, partly in fear of government ‘sanctions’ of one form or another during the Meciar era, but also because the capacities of rural populations for accessing external resources were still more depressed than in the Czech case, where the drive for urbanisation (and therefore the disruption of stable communities) was not as pronounced as in Slovakia, especially from the 1970s.12 But the 1998 general election campaign proved to be a significant turning point, characterised by the mobilisation of a ‘civic democratic’ alliance between the non-governmental and self-government sectors (headed by G3S and the two Slovak local government associations) calling for a fundamental change in the ‘character of the state’. This was a natural alliance within the polarised social conditions of Slovakia: opinion surveys from 1995 identified a strong correlation between membership in various kinds of civic association and local councils, delimiting an active citizenry sharing a distinctive set of values (above all a commitment to a ‘democratic’ as opposed to a ‘techno-cratic’ conception of the state) and a strong ‘sectoral identity’ (first mobilised during the Third Sector SOS campaign in 1996 against the restrictive terms of a proposed law on foundations) (‘Beseda’ 1996: 264). Cooperation has continued both in pushing for decentralisation of competences and other public sector reforms promoting subsidiarity, public participation and sustainable development, and in realising practical communitarian projects, many of which have been institutionalised in the form of community coalitions or foundations. In different places these have developed either from NGO attempts to establish local coordinating centres, pool resources and accumulate a capital base for long-term project financing, or from local authority initiatives to set up funds to stimulate the growth of a local civic sector (J. Mesík: Nonprofit no. 3, 1998; M. Minarovic: Nonprofit no. 3, 1999).

According to the SAIA-SCTS database of NGOs (HTTP: <http://www.saia.sk>), Humenné district has a relatively high concentration of voluntary organisations in comparison with the Prešov region as a whole, which itself ranks third out of the eight regions of Slovakia measured by the ratio of population to NGO numbers (behind only Bratislava and Košice, the country's two dominant urban regions). Humenné also saw the establishment of a community foundation in 2000, the starting capital for which was provided in equal measure by the council and the Open Society Foundation (Korzár 23 March 2001). Alongside SKOI and POF this constitutes another initiative recalling some of the original goals of VPN — building social capital, stimulating civic engagement and thereby enhancing the community's extensive local autonomy as well as people's quality of life. In 2001 it successfully competed for inclusion (as one of four Slovak towns) in a pilot urban social and economic planning scheme run by the Czech-American Berman Group consultancy firm and financed by USAID, which is designed to bring together key actors within the community. By contrast Medzilaborce (since 1996 a separate administrative district) has the lowest level of NGO activity in the region, and Snina also has a lower than average concentration (‘Tretí sektor v Prešovskom kraji’, Nonprofit no. 12, 1999, plus own calculations from SAIA-SCTS database). One of the factors behind this disparity may well be the formative role played by VPN in the emergence of a network of civic activists in Humenné and the lack of such a stimulus in Medzilaborce and Snina, where what little civic activity VPN generated was later absorbed by a single unifying ethnic identity (in Medzilaborce) or channelled into narrow personal and party interests (in Snina).

Civic Forum

The following section describes of the impact of Civic Forum on the life of five west and central Bohemian municipalities during and after 1990, based on the testimony of their mayors. All were elected in the November 1990 elections, and served until at least 1994. The first part provides a pen-portrait of each place, highlighting the most notable features of their development during the initial phase of post-communist transformation. The accounts are ordered according to a rough categorisation of two ‘positive’, one ‘mixed’ and two ‘negative’ cases, based on the scenarios hypothesised in the introduction, as well as on interviewees' own evaluations. The second part is structured around four variables which enable a more systematic assessment of the success or failure of OF in restoring the extensive local autonomy of communities and offer a framework for comparison with more generalised examples. These are representation, self-representation (narrativising and projecting), self-regulation (autonomous decision-making) and the reintegration of local public spaces (including the successorship of OF as political subjects).

Case studies

Positive cases

S.P. is a small town in the west Bohemian countryside with around 3,000 inhabitants. With a poor infrastructure in 1989, two of the main achievements of the first democratically elected local council were the building of an ecological water treatment plant (which became a model for other municipalities near and far) and the reconstruction of a disused country house for a small church secondary school. Although these projects were initiated by the council, they relied substantially on the willingness of citizens to help out in the form of voluntary brigade work. Furthermore both were of a nature which demanded considerable initial investment and sacrifice by the whole community, and only promised a return (water quality and a cleaner environment, educational opportunities for children) in the medium to long-term. Commenting on the victory of his electoral list (by now a grouping of ‘independent’ candidates) in the 1994 elections, the former mayor wrote:

We had not made any populist gestures. On the contrary we had constantly chided, guided and perhaps educated people… . I did not anticipate victory, and I took it as an unequivocal sign of endorsement of the work we had done at the town hall in the past four years.

(‘Learning Democracy’ archive)

Although OF itself ceased to exist in 1991, many of its leading activists — now independent councillors — and its politics of community mobilisation can be said to have become ‘institutionalised’ in the emerging self-government organs of the town. One of the keys to success was remaining sensitive to the traditional structure of public affairs, working closely with existing social organisations (notably the voluntary fire brigade), fostering an atmosphere of non-partisan cooperation (embracing even communist representatives) within the council chamber and refraining from making wholesale changes among the council staff, where their experience was needed. The mayor stood down voluntarily in 1994 (continuing as an ordinary councillor) and handed over the stewardship of the community to a young, energetic successor who had also been in OF, and who had served a four-year ‘apprenticeship’ as deputy mayor. Explaining his decision to stand down, the mayor wrote: ‘I had to leave so that people understood that democracy is everyone's responsibility… . I wanted the citizens of S.P. to look on a job in the council as a service.’

J. is a small town (population just over 3,000) within commuting distance of Prague. The course of the velvet revolution here was conditioned by this proximity, which meant that many inhabitants experienced the major demonstrations first-hand, and succeeded in infusing local life with some of the optimism about civic renewal which was naturally strongest in Prague itself. J. had a number of specific developmental handicaps — relative poverty, dependence on one large, heavily subsidised agricultural cooperative for employment, an over-burdening of the local environment by weekend tourists from Prague (with over 1,500 weekend cottages in the area)13 and, according to the ex-mayor, a typically petit-bourgeois social milieu. The local OF first took shape within the agricultural cooperative, but soon became primarily concerned with communal affairs. These included two ‘burning issue’ — the future use of a special ‘mobilisatory’ hospital located in the municipality, and resistance to plans for a motorway extension which would have cut through a locally cherished, hitherto unspoiled valley. These issues helped mobilise a local patriotism which overrode most internal sources of Fričtion and enabled the local OF group to collaborate with the national committee, which remained largely unreconstructed until the November 1990 elections (which OF, in a coalition with the People's Party, won convincingly). Until then OF, partly due to a cautious approval of the communist council leadership, partly in a spirit of democracy, took on the role of unofficial opposition, ‘mapping’ local problems and involving as wide a public as possible in the search for solutions, which were then written into its local election programme. The Swiss model of self-government, involving the widespread use of local referenda, was promoted and, at least informally, put into practice, and a well-written newsletter began to come out, informing citizens about their new rights and responsibilities as well as raising local issues. The core of the movement was viewed as a reservoir for the future civic leadership of J., and members (later councillors) were sent on courses and workshops designed to nurture management and leadership capabilities or communication skills. After the elections, ordinary councillors were invited to participate in council (leadership) meetings in order to foster a broader democratic accountability and incorporate more people into the decision-making process. OF became the crux of a network of social organisations, including the reinvigorated People's Party, the voluntary fire brigade, the Czech Tourists' Club and the evangelical Czech Brotherhood Church. Their common goal was to re-establish J. as an independent entity in relation to higher administrative bodies (J. quickly took up its new right to establish a local police station, for example). In contrast to S.P. the dissolution of OF was followed more or less automatically by the establishment of a local ODS branch, but in practice it constituted the straightforward substitution of one organisational base for another, with ODS continuing to function as a means of coordinating the efforts of an active local civic elite (and making it easier to stand for election, since independent candidates, unlike parties, have to gather signatures). In fact the ex-mayor of J. (now a regional MP) left ODS following the financial scandals which led to the downfall of the last Klaus government, joining the breakaway Freedom Union (US).

Mixed cases

Ř. also serves partly as a dormitory town for Prague, although it is larger than J., with a population of 11,000. It retains a relatively stable social structure which reflects the period of its most rapid growth in the 1930s. Its generally unruffled existence was threatened by plans hatched in the 1970s for what would have been the largest prison in Europe, a new industrial zone and a planned expansion in the population to 30,000. This provided an important mobilisatory issue for Civic Forum, and, as in J., the (successful) protest against ‘Prague's’ plans to dump its problems in Ř. fed into a movement to restore local self-determination and to reshape its relations with higher-level administrative authorities on the basis of partnership instead of hierarchical directives: ‘The town wants to live its own life again, as it once did. We are willing to reach agreement with the government if it has essential, justified intentions. But it must not be a humiliating agreement’ (two OF spokespeople quoted in Respekt no. 10, 1990).

Nonetheless OF was not as successful here at reintegrating the town's public space as in S.P. and J.This was partly attributed by the ex-mayor to the effect of Prague siphoning off potential civic activists — many of those who worked in Prague felt more of an affiliation with their workplace and engaged in Civic Fora established there. OF set up expert commissions to shadow the work of the national committee, which were integrated into the council administration after January 1990, when fourteen OF members were co-opted onto the council, one as its chairman. Ř. OF immediately identified the local administrative structures as the target of its action, and laid the foundations for efficient, democratic local government, but in comparison with the first two examples neglected the extensive self-governing structures of public life, failing to engage with or stimulate a revival of social and cultural activity generally. Moreover, when OF split in 1991 fissures also appeared in R., where ODS grouped a number of councillors opposed to the OF mayor. The small Socialist and People's Party groups on the council had already turned against OF, and the period of re-establishing a collective self-regulating ethic was quickly substituted by a disintegration of intracommunity relations into competing interest groups. This may reflect the differing social dynamics of a slightly larger town, where more stratified patterns of social interaction were rapidly visible following the establishment of a basic market economy. Thus although OF in Ř. succeeded in liberating creative energies latent within the community, this was not manifest in patterns of collective identification or social integration.14

Negative cases

Z. is a village of 500 people in western Bohemia, close to S.P. Civic Forum was quickly established there and its burgeoning popularity was reflected in electoral success in both the June 1990 general election and in the November local election results, which led to its candidate taking the mayoralty. A large response to a questionnaire about local problems and priorities, organised in the village by OF, indicated enthusiasm for a participatory self-government, and the results proved an invaluable guide for the first steps of the new council, according to the then mayor. But, as the activity of OF itself began to concentrate around a core of ten to fifteen people, the organisation started to drift towards a more elitist mode of operation, facilitated by indifference towards and inexperience with public affairs among the wider local population. There were no particularly urgent local issues to maintain a high level of public interest in communal politics, but proposals for ‘radical’ development projects by the OF mayor (such as for the construction of a holiday camp nearby, or for the transformation of the local consumer cooperative) evoked a strong negative reaction in a conservative rural social milieu, uncovering a latent preference for continuity in village life. By contrast public opinion proved a feeble antidote to the alleged manipulation of the tendering process for a social housing investment to the benefit of relatives of council leaders, an issue which led to the mayor's removal in 1996, because he opposed such practices. OF had not precipatated the recall of the communist national committee leadership in 1990, but most of the communist representatives withdrew from public life at the November elections and the Communist Party organisation itself slowly petered out. With hindsight the former mayor (for OF until 1991, then for its centre-left successor party Civic Movement) expresses regret about their retirement — in his view the communist municipal leadership was a better manager of local development and more responsible guardian of public finances than his former colleagues within OF (who remain in charge today).

L. is a very small village (population 270) in central Bohemia. It represents a widespread process in the Czech and Slovak countryside after 1990, when the new law on municipal government enabled communities which had been run as administrative sub-units from neighbouring larger parishes to re-establish their autonomy in local self-government. The people of L. thus opted through a petition to return to the independent status their community had enjoyed until 1975.15 However this proved to be a one-off engagement in public affairs (albeit extending to a very high turnout in the first local elections), and there is little evidence of much local patriotism in L. today: there are no functioning social organisations other than the Sokol sports club, and the only communal life revolves around the pub and Sokol, and specifically around an annual fundraising country music festival cum sports tournament. Civic Forum did not last long, and although some of its prime movers later joined ODS, their influence within the community was based on an ability to manipulate informal social networks and procedures where, as the former mayor put it, ‘decisions are taken in the pub and then ratified by the council’. OF thus had a marginal effect on civic culture in L., and may indeed have contributed to establishing the legitimacy of a small local ‘clan’ which has largely been able to direct public resources towards its own private interests with impunity, since public expectations of local representative institutions are so low. As in Z., the first (OF) mayor of L. proved unable to generate a revival of civic culture (despite its size L. had a rich associative life up to the 1930s) and as a result found himself impotent against the power of local clans, who ultimately engineered his premature replacement. The history of post-revolutionary social change in both Z. and L. matches the conclusions of an earlier study of eleven small villages — ‘public life has been extinguished (new interest organisations did not emerge, while old ones did not activise and some disappeared, nor was there even a revival in religious life)’ (Heřmanová et al. 1992: 372).

Revival of extensive local autonomy

Representation