Chapter 6

Differentiating Customers by Their Needs

I don’t know the key to success, but the key to failure is trying to please everybody.

—Bill Cosby

All value for a business is created by customers, but the reason any single customer creates value for a business is to meet that particular customer’s own individual needs. While it’s important to recognize that different customers will create different amounts of value for the enterprise (i.e., some customers are worth more than other customers, a subject we explored in Chapter 5), it’s even more important to understand how customers differ in terms of their individual needs, and this is the topic we will tackle in this chapter. Individual customer valuation methods are fairly well established as an important stepping-stone for managing the customer-strategy enterprise. Academics and business professionals alike spend much time and energy testing the effectiveness of alternative methods and models. But differentiating customers based on their needs is still a relatively new idea, not as widely practiced by companies—not even by those professing to take a customer-centric approach to business. At its heart, needs differentiation of customers involves using feedback from an identifiable, individual customer to predict that customer’s needs better than any competitor can who doesn’t have that feedback. In addition to categorizing customers by their value profiles (see Chapter 5), it is vital to categorize customers based on their individually expressed needs, when they are similar. This is the only practical way to set up criteria for treating different customers differently.

Having a good knowledge of customers’ value is certainly important, but to use customer relationship management (CRM) tools and customer strategies to increase a customer’s value, the business must be able to see things from the customer’s perspective, with the realization that there are many different types of customers whose perspective must be individually understood. Value differentiation by itself will not give a company this perspective. Think about it: Customers don’t usually know or care what their value is to a business. Customers simply want to have their problem solved, and every customer has his own slightly different twist on how the process should be handled, even if more than one customer wants a problem solved a particular way. The key to building a customer’s value is understanding how this customer wants it solved. So one key to building profitable relationships is developing an understanding of how customers are different in terms of their needs and how such needs-based differences relate to different customer values, both actual and potential. What behavior changes on the customer’s part can be accomplished by meeting those needs? What are the triggers that will allow the firm to actualize some of that unrealized potential value?

In this chapter, we consider the different needs of different customers and the role that customer needs to play in an enterprise’s relationship-building effort. In most situations, it makes sense to differentiate customers first by their value and then by their needs.1 In this way, the relationship-building process, which can be expensive, will begin with the company’s higher-value customers, for whom the investment is more likely to be worthwhile. (An important exception to this general rule, however, applies to treating different customers differently on the World Wide Web. On the Web, the incremental costs of automated interaction are near zero, so it makes little difference whether an enterprise differentiates just its top customers by their needs or all its customers.)

Definitions

Before going too much further, let’s pause to define the important terms relevant to this discussion.

Needs

When we refer to customer needs, we are using the term in its most generic sense. That is, what a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, what she wants, what she prefers, or what she would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but to simplify our discussion, we will refer to them all as “needs.”

It is what a customer needs from an enterprise that is the driving force behind the customer’s behavior. Needs represent the “why” (and often, the “how”) behind a customer’s actions. How customers want to buy may be as important as why they want to buy. The presumption has been that frequent purchasers use the product differently from irregular purchasers, but it may be that they alternatively or additionally like the available channel better. For that matter, it may be that they like the communications channel better. The point is that needs are not just about product usage but about an expanded need set (which we discuss fully in Chapter 10) or the combination of product, cross-buy product and services opportunities, delivery channels, communication style and channels, invoicing methods, and so on.

In a relationship, what the enterprise most wants is to influence customer behavior in a way that is financially beneficial to the enterprise; therefore, understanding the customer’s basic need is critical. It could be said that while the amount the customer pays the enterprise is a component of the customer’s value to the enterprise, the need that the enterprise satisfies represents the enterprise’s value to the customer. Needs and value are, essentially, both sides of the value proposition between enterprise and customer—what the customer can do for the enterprise and what the enterprise can do for the customer.

Customers

Now that we have defined both customer value and customer needs, we should pause for a reminder of the definition of customer before continuing with our discussion. In Chapter 1, we defined what we mean by customer. On the surface, the definition should be obvious. A customer is one who “gives his custom” to a store or business; someone who patronizes a business is the business’s customer. However, the overwhelming majority of enterprises serve multiple types of customers, and these different types of customers have different characteristics in terms of their value and their individual needs.

A brand-name clothing manufacturer, for instance, has two sets of customers: the end-user consumers who wear the clothes and the retailers that buy the clothes from the manufacturer and sell them to consumers. As a customer base, clothing consumers do not have as steep a value skew as, say, a hotel’s customer base, even though some consumers might buy new clothes every week. (In other words, the discrepancy in value between the very most valuable consumers and the average will generally be smaller for a particular clothing merchant.) But all consumers of the clothing manufacturer do want different combinations of sizes, colors, and styles. So even though clothing consumers may not be highly differentiated in terms of their value, they are highly differentiated in terms of their needs. Retailer customers also have very different needs: Some need more help with marketing, or with advertising co-op dollars, or with displays. Different retailers will have very different requirements for invoice format and timing or for shipping and delivery. They may need different palletization or precoded price tags. Interestingly, retailers will also vary widely in their values to the clothing manufacturer—with much more value skew than consumers will show. Some large department store chains will sell far more stock than can a local mom-and-pop clothing shop. Thus retailer customers display high levels of differentiation in terms of both their needs and their value.

For the clothing manufacturer, if the enterprise expresses an interest in improving its relationships with its customers, the question to answer is: Which customers? And this is, in fact, the type of structure in which most enterprises operate. They won’t all sell products to retailers, but the vast majority of businesses do have distribution partners of some kind—retailers, dealers, brokers, representatives, value-added resellers, and so forth. Moreover, a business that sells to other businesses, whether these business customers are a part of a distribution chain or not, really is selling to the people within those businesses, people of varying levels of influence and authority. Putting in place a relationship program involving business customers will necessarily entail dealing with purchasing agents, approvers, influencers, decision makers, and possibly end users within the business customer’s organization, and each of these people will have quite different motivations in choosing to buy.

The logical first step for any enterprise embarking on a relationship-building program, therefore, is to decide which sets of customers to focus on. A relationship-building strategy aimed at end-user consumers can (and in most cases, should) involve some or all of the intermediaries in the value chain in some way. However, it is a perfectly legitimate goal to seek stronger and deeper relationships with a particular set of intermediaries. The basic objective of relationship building with any set of customers is to increase the value of the customer base; thus, it’s important to understand from the beginning exactly which customer base is going to be measured and evaluated. Then, when focusing on that customer base, the enterprise must be able to map out its customers in terms of their different values and needs.

Companies create products and services with benefits that are specifically designed to satisfy customer needs, but the benefits themselves are not equivalent to needs.

It is easy to confuse a customer’s needs with a product’s benefits. Companies create products and services with benefits that are specifically designed to satisfy customer needs, but the benefits themselves are not equivalent to needs. In traditional marketing discipline, a product’s benefits are the advantages that customers get from using the product, based on its features and attributes. But features, attributes, and benefits are all based on the product rather than on the customer. Needs, in contrast, are based on the customer, not the product. Two different customers might use the same product, based on the same features and attributes, to satisfy very different needs.

When it focuses on the customer’s need, the enterprise will find it easier to increase its share of customer, because ultimately it will seek to solve a greater and greater portion of the customer’s problem—that is, to meet a larger and larger share of the customer’s need. And because the customer’s need is not directly related to the product, meeting the need might, in fact, lead an enterprise to develop or procure other products and services for the customer that are totally unrelated to the original product but closely related to the customer’s need. That’s why focusing on customer needs rather than on product features often will reveal that different customers purchase the same product in order to satisfy very different individual needs.2

Demographics Do Not Reveal Needs

Thirty years ago, a groundbreaking marketing article asked: “Are Grace Slick and Tricia Nixon Cox the same person?” Grace Slick, lead singer for the rock group Jefferson Starship, and Tricia Nixon Cox, the preppy daughter of Richard Nixon who married Dwight Eisenhower’s grandson, were demographically indistinguishable. They were both urban, working women, college graduates, age 25 to 35, at similar income levels, household of three, including one child.

What made this question startling in the early 1970s was that it undermined the validity of the traditional demographic tools that marketers had been using for decades to segment consumers into distinct, identifiable groups. With demographic statistics, mass marketers thought they could distinguish a quiz show’s audience from, say, a news program’s. Then marketers could compare these audiences with the demographics of soap buyers, tire purchasers, or beer drinkers. The more effectively a marketer could define her own customers and target prospects, differentiating this group from all the other consumers who were not her target, the more efficiently she could get her message across. She could buy media that would reach a higher proportion of her own target audience.

But demographics could not explain the distinctly nondemographic differences between Grace Slick and Tricia Nixon Cox. So, as computer capabilities and speeds grew, marketers began to collect additional information to distinguish consumers, not by their age and gender, but by their attitudes toward themselves, their families and society, their beliefs, their values, their behaviors, and their lifestyles.

Source: Excerpted from Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, Ph.D., The One to One Future (1993), in reference to John O’Toole, “Are Grace Slick and Tricia Nixon Cox the Same Person?” Journal of Advertising 2 (1973): 32–34.

Differentiating Customers by Need: An Illustration

Consider a company that manufactures interlocking toy blocks for children, such as LEGO Lego® or MEGA Bloks®, and suppose this firm goes to market with a set of blocks suitable for constructing a spaceship. Three seven-year-old children playing with this set of blocks might all have different needs for it. One child might use the blocks to play a make-believe role, perhaps assembling a spaceship and then pretending to be an astronaut on a mission to Mars. Another child might enjoy simply following the directions, meticulously assembling the same spaceship in exact detail, according to the instructions. Once the ship is built, however, the child would be less interested in it. A third child might use the block set meant to construct a spaceship to build something entirely different, drawn from his own vivid imagination. This child simply wouldn’t enjoy putting together a toy according to someone else’s diagram.

Each of these three children may enjoy playing with the same set of blocks, but each is doing so to satisfy a different set of needs. Moreover, it is the child’s need that, if known to the marketer, provides the key to increasing the child’s value as a customer. If the toy manufacturer actually knew each child’s individual needs, and if it had the capability to deal with each child individually, by treating each one differently, it could easily increase its share of each child’s toy-and-entertainment consumption. For example, for the “actors,” it might offer costumes and other props, along with storybooks and videos or DVDs, to assist the children in their imaginative role-playing activities. For the “engineers,” it might offer blueprints for additional toys to be assembled using the spaceship set; or it might offer more complex diagrams for multiset connections. And for the more creative types, the “artists,” the company might provide pieces in unusual colors or shapes, or perhaps supplemental sets of parts that have not been planned into any diagrams at all.

We can use this example to compare and contrast the different roles of product attributes and benefits versus customer needs. Exhibit 6.1 shows that each product attribute yields a particular benefit that consumers of the product can enjoy.

EXHIBIT 6.1 Product Attributes versus Benefits

| Product Attribute | Product Benefit |

| Toys in fantasy configurations | Recognizable make-believe situations |

| Colorful, unusual shapes that easily interlock | Large variety of interesting combinations |

| Meticulously preplanned, logically detailed instructions | Complex directions that are nevertheless easy to follow |

It should be easy to see that each product attribute can be easily linked to a particular type of benefit. And the benefits will appeal differently to different customers, but each benefit springs directly from each attribute. If, instead, we were to map out the types of customers who buy this product, based on the needs of these end users as just outlined, we could then list the additional products and services that each type of customer might want, based on what that customer needs from this and other products. If we just looked at our actor, artist, or engineer end-user customers to see which needs they wanted to address, then our table would look like Exhibit 6.2.

EXHIBIT 6.2 Beyond Benefits: Customer Needs

| Customer Need | Additional Products and Services |

| Actor: Role-playing, pretending, fantasizing | Costumes, videos, storybook, toys |

| Artist: Creating, making stuff up, doing things differently | Colors and paints, unique add-ons, nonsequitur parts |

| Engineer: Solving problems, completing puzzles | More diagrams, problems, logical extensions |

This is only a hypothetical example, of course, and we could easily come up with several additional types of customers, based on the needs they are satisfying with these construction blocks. For instance, there might be some girls who want the spaceship set of blocks because they are really interested in rockets, outer space, and other things astronautical. Or there might be some boys who want the set because they are collectors of these kinds of building-block toys, and they want to add this to a large set of other, similar toys. Or there might be others who like to use this kind of toy to invite friends over to work together on the assembly. Any single child might, in fact, have any combination of these needs that she wishes to satisfy, either at different times or in combination.

The point is, by taking the customer’s own perspective, the customer’s point of view—by concentrating on understanding each different customer’s needs—the enterprise will more easily be able to influence customer behavior, and changing the future behavior of a customer by becoming more valuable to him is the key to realizing additional value from that customer.

Scenario: Financial Services

A large B2B financial services organization faced both increasing competition and product commoditization.a The customers of this firm are channel members—the brokers and financial advisors (FAs) who sell stocks and bonds and other financial instruments to consumer clients from their own business. The enterprise sought to increase loyalty and reduce the effects of cost cutting among these channel-member customers by meeting their individual needs, one customer at a time. Research, based on interviews with the enterprise’s sales staff and customers, uncovered several key customer needs.

Five needs-based portfolios were identified and given nicknames—High-Potential Newbies, Marketing Machines, Active Growers, Transitional Players, and Cruise Controls—in a research project that combined customer needs information with customer valuation. As a result, the enterprise determined its customers’ needs while at the same time uncovering which high-value customers posed the greatest defection risk. This led to the development of a defection reduction strategy to retain those customers. For customers not at risk of defection, the organization developed interaction strategies to begin meeting their needs immediately.

As it builds relationships with these customers over time, the financial services enterprise will seek to increase customer knowledge and to act on the individual needs of its customers. In the process, both the enterprise and its customers will benefit. For the enterprise, an interaction strategy for each FA, based on the individual FA’s needs and value, will provide clear direction and focus for the sales force. As more needs are uncovered, the firm will be able to offer more products and services. Ultimately, defection will be reduced, which should substantially reduce marketing and sales costs.

For the customers themselves, the relationship-building program should improve the relevance and usefulness of incoming information from the enterprise. This will enable individual FAs to run their own businesses faster, more efficiently, and in a way that is likely to please their own clients more.

aThanks to Jennifer Monahan, Nichole Clark, Laura Cococcia, Bill Pink, Valerie Popeck, and Sophie Vlessing for the ideas here.

Understanding Customer Behaviors and Needs

Kerem Can Özkısacık, Ph.D.

Manager, Middle East, Peppers & Rogers Group

Understanding the differences in customer behaviors, and the needs underlying these behaviors, is critical for all stages in a company: from product development to financial consolidation, from production planning to strategic planning or marketing budgeting. All decisions and activities made by customers in order to evaluate, purchase, use, and dispose of any goods or services offered by a company are subject to being captured in the transactional record and are subject to behavioral analysis.

A customer’s need is what she wants, prefers, or wishes while her behavior is what she does or how she acts in order to satisfy this need. In other words, “needs” are the “why” of a customer’s actions, and “behaviors” are the “what.” Behaviors can be observed directly, and from behaviors an enterprise can often infer things about a customer’s needs. This hierarchy or logical ordering in these two notions, that customer needs drive customer behaviors, is a critical pillar for the relationship-marketing practitioner.

All companies want to understand why and how customers make their buying decisions. Factors that affect this process are analytically assessed and examined, then reexamined. Clearly segmenting customers by their needs and behaviors will allow an enterprise to identify and describe different categories of customers and ensure that its marketing efforts are effective for each of these groups.

Characterizing Customers by Their Needs and Behaviors

Companies now have comprehensive systems and processes to capture and store customer data covering almost every aspect of a customer’s relationship with a firm. Descriptive characteristics like gender, age, and income, along with transactional data such as interactions, purchases, and payments, and usage-related measures such as service requests—all this information can be captured and stored by the enterprise. The information companies store on individual customers is usually referred to as customer profiles.

Now let’s consider a customer database in a bank environment where there has been a significant information technology (IT) investment. The department in charge of business intelligence can describe the same customer in two different ways, providing two different profiles:

1. Customer is married, is European, has two children, lives in an upscale neighborhood, and is a member of a frequent-flyer program.

2. Customer visited the online banking site once a week over the last six months, always visiting the site at least once in the first three days of each month; has a tenure of more than two years; uses investment tools; checks her statement and balance regularly; pays her credit debts promptly and has a clear credit history; and has increased her assets under management by 5 percent in the last three months.

The first profile is demographic. It is a set of characteristics that are less dynamic compared to the second profile. These data probably are stored by other companies doing business with this customer as well, and perhaps even by the bank’s own competitors. The second profile is behavior-based, and involves a record derived from what the customer is actually doing or has done in the past with this bank. Details of her behavior are dynamic and only available inside the bank’s database, thus providing the bank with an opportunity for competitive advantage—if the bank uses the information to serve this customer better than other firms that do not have the specific customer information.

Both profiles are important in their own ways. For someone preparing an advertising campaign, creating a marketing strategy, or deciding on content for a piece of marketing communication, the first profile is very useful, because it defines the customer (or the market) at a macro level and provides clues to editorial direction. If someone in the bank’s marketing department just wanted to describe this customer to someone else, this is the profile they would probably use. The second type of profile, however, is about action and behavior, and is certainly more relevant than the demographic profile for any executive at the bank who really wants to know what customers are doing. Will this customer visit again? Will she buy again? What is the risk she will default on her credit, or cost the bank money? These are the questions an executive tries to answer by looking at behavioral records.

But let’s now assume that the business intelligence department can produce a third profile on this customer as well:

3. The customer the future of her family and her children very carefully, and this is her primary motivation while using the bank’s products and services. She is comfortable with technology and enjoys engaging with the bank online rather than having to visit branches, because she is always pressed for time.

This new profile actually defines why this particular customer uses the banking services she uses. It shows why she prefers online services and why she has accumulated an investment account. Moreover, while different customers will have different needs, many of these needs will be shared by others. Needs describe the root causes behind a customer’s actions, whether those actions include choosing to work with another bank or staying loyal to this bank and subscribing to a new service.

It’s important to get the sequence right also. Needs are not based on a customer’s value or behavior. Rather, a customer’s needs drive her behavior, and her behavior is what generates her value to the business. The needs just described are not generic, true-for-everybody statements, such as “I want to have cheaper products with higher quality.” They are very specific needs, valid only for some portion of the bank’s customers.

Behaviors are the customers’ footprints on a company.

Behaviors are the customers’ footprints on a company. They represent the evidence of customers trying to meet their needs, and this evidence is likely to be accumulated in different company systems over different periods of time.

Needs May Not Be Rational, but Everybody Has Them

In his groundbreaking book, Predictably Irrational,a Dan Ariely makes the case that humans are irrational in what they want and what they do, but—oddly enough—in completely predictable ways. Some of the research he cites draws from lab work on rats and other animals. In one of the most telling studies, mice were offered a food pellet instantly if they pressed a green button. If, instead, they pressed a purple button, they could get 10 pellets, but they had to wait 10 whole seconds, which must seem like forever in mice time. If they pressed the purple button, and—while they were waiting for the big reward—had a chance to press the green button, they could not stop themselves and just had to press the green button—even after they figured out that pressing the green button stopped the delivery of the 10 pellets from the purple button. They learned that if they could not (and therefore did not) press the green button, but they had already pressed the purple button, they did in fact get their 10 pellets after a delay.

What did they do about this situation? Enter the red button, which, as it turns out, makes it impossible to press the green button. So the mice learned to press the purple button, then immediately press the red button, then press the green button all they wanted, but since pressing the red button had turned off the green button, the mice still got to collect the big win of 10 pellets.b

And this is just lab rats, managing to balance their own short- and long-term goals. Can companies do as well? And can we understand that the same customer wrestles with multiple kinds of needs at the same time?

This customer needs thing: It’s complicated.

aDan Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions (New York: HarperCollins, 2008).

bParaphrased from a story told by Dan Ariely in a keynote address to the Duke University Fuqua School of Business Marketing Club annual conference, January 27, 2010.

Why Doesn’t Every Company Already Differentiate Its Customers by Needs?

It is reasonable to ask, if the logic outlined is so compelling, why toy manufacturers and other firms aren’t already attempting to differentiate customers by needs. But keep in mind that the hurdles to doing so are sizable. For one thing, most toy manufacturers sell their products through retailers and have little or no direct contact with the end users of their products. In order to make contact with consumers, a manufacturer will have to either launch a program in cooperation with its retailing partners or figure out how to go around those retailers altogether—a course of action likely to arouse considerable resentment among the retailers themselves. So the majority of a manufacturer’s end-user consumers are destined to remain unknown to the enterprise. Moreover, even if it had its customers’ identities, the manufacturer still would have to find some means of interacting with the customers individually and of processing their feedback, in order to learn their genuine needs. Then it would have to be able to translate those needs into different actions, requiring a mechanism for actually offering and delivering different products and services to different consumers.

These obstacles make it very difficult for toy manufacturers simply to leap into a relationship-building program with toy consumers at the very end of the value chain. That said, the manufacturer does not have to launch such a program for all consumers at once. Rather, it could start by identifying its most avid fans, its highest-volume, most valuable consumer customers. Perhaps it could devise a strategy for treating each of those highly valuable customers to individually different products and services, in a way that wouldn’t undermine retailer relationships. A Web site designed to attract and entertain such consumers could play this kind of role, and the toymaker could take advantage of social networking connectivity as well. Although the toy manufacturer still would encourage other shoppers to buy its products in stores, perhaps it could begin to offer more specialized sets and pieces directly to catalog and Web purchasers. If it had a system for doing this, launching a program designed to make different types of offers to different types of end-user consumers—based on their individual needs— would be much simpler and would, for practical reasons, start that process with customers of high value.

Indeed, the primary reason so many firms are now attempting to engage their customers in relationships is that the new tools of information technology—not just the World Wide Web in general and social networking sites in particular, but customer databases, sales force automation, marketing and customer analytics applications, and the like—are making this type of activity ever more cost-efficient and practical. But for an enterprise engaged in relationship building, the “hot button,” in terms of generating increased patronage from the customer, is the customer’s need.

Categorizing Customers by Their Needs

In the end, behavior change on the part of the customer is what customer-based strategies are all about. To capture any part of a customer’s unrealized potential value requires us to induce a change in the customer’s behavior; we want the customer to buy from an additional product line, or take the financing package as well as the product, or interact on the less expensive Web site rather than through the call center, and so forth. This is why understanding customer needs is so critical to success. The customer is master of his own behavior, and that behavior will change only if our strategy can appeal persuasively to his needs. Being able to see the situation from the customer’s point of view is key to any successful customer-based strategy.

But in order to take action, at some point, different customers must be categorized into different groups, based on their needs. Clearly, it would be too costly for most firms to treat every single customer with a custom-designed set of product features or services. Instead, using information technology, the customer-focused enterprise categorizes customers into finer and finer groups, based on what is known about each customer, and then matches each group with an appropriately mass-customized product-and-service offering. (More about mass customization and the actual mechanics of the process in Chapter 10.)

One big problem is the complexity of describing and categorizing customers by their needs. There are as many dimensions and nuances to customer needs as there are analysts to imagine them. For consumers, there are deeply held beliefs, psychological predispositions, life stages, moods, ambitions, and the like. For business customers, there are business strategy differences, financial reporting horizons, collegial or hierarchical decision-making styles, and other corporate differences—not to mention the individual motivations of the players within the customer organizations, including decision makers, approvers, specifiers, reviewers, and others involved in shaping the company’s behavior.

Marketing has always relied on appealing to different customers in different ways. Market segmentation is a highly developed, sophisticated discipline, but it is based primarily on products and the appeal of product benefits rather than on customers and their broader set of needs considered in a holistic fashion for each individual customer. To address customers as different types of customers, rather than as recipients of a product’s different benefits, the customer-based enterprise must think beyond market segmentation per se. Rather than grouping customers into segments based on the product’s appeal, the customer-based enterprise places customers into portfolios based primarily on type of need.

A market segment is made up of customers with a similar attribute. A customer portfolio is made up of similar customers. The market segmentation approach is based on appealing to the segment’s attribute while the customer portfolio approach is based on meeting each customer’s broader need, based on the customer’s own worldview. If segments and portfolios were made up of toys, then red fire trucks might be in a segment of toys that included red checkers sets, red dolly makeup lipsticks, and red blocks. But red fire trucks would be in a portfolio of toys that included ambulances, fireboats, police cars, and maybe medical helicopters, along with fire hats and axes, stuffed Dalmatians, and ladders. A market segment might be composed of women, over age 45, with household incomes in excess of $50,000. A portfolio of customers might be made up of women who value friendships and like to entertain.

In Chapter 13, we discuss customer management, including the grouping of customers into portfolios. There is a continuing role for traditional market segmentation, even in a highly evolved customer-strategy enterprise, because understanding how a product’s benefits match up with the attributes of different customers continues to be an important marketing activity. But as the enterprise gains greater and greater insight into the actual motivations of particular categories of customers, it will find that managing relationships cannot be accomplished in segment categories, because any single customer can easily be found in more than one segment. Instead, when they take the customer’s perspective, the managers at a customer-strategy enterprise will learn that they must meet the complex, multiple needs of each customer, as an individual. And doing this will require categorizing customers according to their own, broader needs rather than according to how they react to the product’s individually considered attributes and benefits. Each customer can appear in only one portfolio.

A single customer can be found in more than one customer “segment” but in only one customer “portfolio.”

Understanding Needs

Understanding different customers’ different needs is critical to any serious relationship-building program. Some of the characteristics of customer needs should be given careful consideration:

- Customer needs can be situational in nature. Not only will two different consumers often buy the same product to satisfy different needs, but a customer’s needs might change from event to event, and it’s important to recognize when this occurs. An airline might think it has two customer types—business travelers and leisure travelers—but in reality this typology refers to events, not customers. Even the most frequent business traveler will occasionally be traveling for leisure, perhaps with a spouse or family instead of the usual solo travel, and in that event she will need different services from the airline than she needs when she travels on business.

- Customer needs are dynamic and can change over time as well. People are changeable creatures; our lives evolve from one stage to another, we move from place to place, we change our minds. Moreover, certain types of people change their minds more often than others, tending to be less predictable. That said, the fact that a certain type of customer is not predictable is a customer characteristic itself, which can be used to help guide an enterprise’s treatment of that customer. Marriage, new babies, and retirement typically lead to profound changes in needs for most people.

- Customers have different intensities of needs and different need profiles. Even when two customers have a similar need, one customer will have that need intensely while the other may feel the need but less intensely and perhaps in a different profile, combined with other needs. One homemaker is committed to running a very “green” kitchen while another wants to take care of the environment where it makes sense, but also has the need to save time as much as possible and may use paper plates so she doesn’t have to spend so much time washing dishes.

- Customer needs often correlate with customer value. Although it is not always true, more often than not a high-value customer is likely to have certain types of needs in common with other high-value customers. Similarly, a below-zero customer’s needs are more likely than not to be similar to other below-zero customers’ needs. A business that can correlate customer value with customer needs is generally in a good situation, because by satisfying certain types of needs, it can do a more efficient job of winning the long-term loyalty of higher-value customers.

- The most fundamental human needs are psychological. When dealing with human beings as customers (as opposed to companies or organizations), understanding the psychological differences among people can provide useful guidance for treating different customers differently.

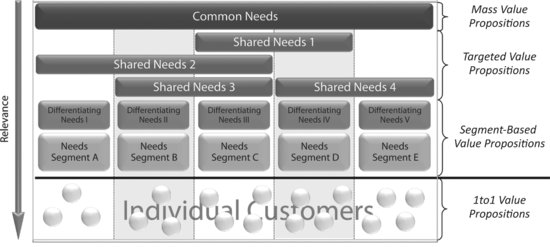

- Some needs are shared by other customers while some needs are uniquely individual. When an online bookstore makes an automated book recommendation to an individual customer, this recommendation is based on the fact that other customers who have bought similar books as this customer has bought in the past have also bought the book being recommended now. There are hundreds of thousands of books a person could buy at an online bookstore, but people who buy similar books do so because they share similar needs. A retailer with a good database of past customer purchases can use “community knowledge,” purchases, and traits found in common among disparate customers, to infer which products the members of a particular community of customers might find more appealing. Software for sorting through groups of customers to find commonalities is called collaborative filtering (more about these concepts later in this chapter). However, if a florist remembers a customer’s wedding anniversary or a relative’s birthday and sends the customer a reminder, the florist is very likely to get a great deal more business, simply by remembering these unique dates for each customer. But any single customer’s wedding anniversary has very little to do with any other customer’s anniversary date. In both the bookstore’s and the florist’s case, individual customer needs are being met, but some needs are unique and personal while some are tastes or preferences that are shared by other customers, as well (see Exhibit 6.3).

EXHIBIT 6.3 Common and Shared Needs of Customers

- There is no single best way to differentiate customers by their needs. As difficult as it is to predict and quantify a customer’s value to the enterprise, at least the final result will be measured in economic terms. Value ranking, in other words, is done in one dimension: the financial dimension.3 But when an enterprise sets out to differentiate its customers by their needs, it is embarking on a creative expedition, with no fixed dimension of reference. There are as many ways to differentiate customers by their needs as there are creative ways to understand the deepest human motivations. The value of any particular type of needs-based differentiation is to be found solely in its usefulness for affecting the different behaviors of different customers.

- Even in business-to-business (B2B) settings, a firm’s customers are not really another “company,” with a clearly defined, homogeneous set of needs. Instead, customers are a combination of purchasing agents, who need low prices; end users, who need benefits and attributes; the managers of the end users, who need those end users to be productive; and so on.

Community Knowledge

In the competition for a customer, the successful enterprise is the one with the most knowledge about an individual customer’s needs. In a successful Learning Relationship, the enterprise acts in the customer’s own individual interest as a result of taking the customer’s point of view. What if the customer were to maintain her own list of specifications and purchases? If the record of a customer’s consumption of groceries were maintained on her own computer rather than on a supermarket’s computer, this would undercut the competitive advantage that customization gives to an enterprise. Each week a whole cadre of supermarkets could simply “bid” on the customer’s list of grocery needs, reducing the level of competition once again to the lowest price. The customer-strategy enterprise can avoid this vulnerability, as it has devised a way to treat an individual customer based on the knowledge of that customer’s transactions as well as on the transactions of many other customers who have similarities to her. This is known as community knowledge.

Community knowledge comes from the accumulation of information about a whole community of customer tastes and preferences. It is the body of knowledge that an enterprise acquires with respect to customers who have similar tastes and needs, enabling the firm actually to anticipate what an individual customer needs, even before the customer knows he needs it. The collaborative filtering software that sorts through customers for similarities is essentially a matching engine, allowing a company to serve up products or services to a particular customer based on what other customers with similar tastes or preferences have preferred in this particular product or service.

Technology has accelerated the rate at which enterprises can apply community knowledge to better understand individual customers. This tool can help not just the individual consumers of a company like an online bookstore, but also B2B customers. The idea of community knowledge has a direct lineage from one of the most important values any B2B business can bring its own business customers: education about what other customers with similar needs are doing—in the aggregate, of course, never individually. Firms know that they must teach their customers as well as be taught by them. An enterprise brings insight to a customer based on its dealings with a large number of that customer’s own competitors. Community knowledge can yield immense benefits to many businesses, but especially to those businesses that have:

- Cost-efficient, interactive connections with customers as a matter of routine, such as online businesses, banks and financial institutions, retail stores, and B2B marketers, all of which communicate and interact with their customers directly and on a regular basis.

- Customers who are highly differentiated by their needs, including businesses that sell news and information, movies and other entertainment, books, fashion, automobiles, computers, groceries, hotel stays, and healthcare, among other things.

Marketing expert Fred Wiersema4 has said that there are three characteristics of market leadership: bringing out the product’s full benefits, improving the customer’s usage process, and breaking completely new ground with the customer. Any one of these types of customer education can come from the knowledge an enterprise acquires by serving other customers. An enterprise with a large number of customers can use community knowledge to lead a customer to a product or service that the enterprise knows the customer is likely to need, even though the customer may be totally unaware of this need. It might be as simple as choosing a hotel in a city the customer has never visited, but it could also apply to pursuing an appropriate investment and savings strategy, even though the customer may not have thought of it yet.

Pharmaceutical Industry Example

Consider, for example, a pharmaceutical company. Traditionally, this firm has not engaged in much relationship building with its end-user consumers (i.e., the patients for whom its drugs are prescribed). Rather, the firm has always considered its primary customers to be the prescribing physicians and other related healthcare professionals, along with pharmacies, employers, some government entities, and healthcare organizations. But now, faced with the cost-efficient, powerfully interactive technology of the World Wide Web, this pharmaceutical company wants to begin to establish genuine, one-to-one relationships with at least some of the more valuable consumers of its products. The company sells medicine for diabetes, which can be kept in check through constant vigilance, but, as is the case with many such diseases, compliance is a problem. Patients often simply fail to keep up the medical treatment or fail to monitor their own condition properly. The company knows that patients want help in understanding and dealing with the disease, so it sets up a Web site to serve as a resource for information and support. The benefits for the pharmaceutical company and for the patient are straightforward: A better-informed and supported patient is likely to exhibit better compliance, which will both keep the patient healthier and sell more of the pharmaceutical company’s drugs.

Knowing that different consumers will need different types of support and assistance, the pharmaceutical enterprise undertakes to design a patient-centric Web site. To do so, it conducts a research survey of patients, and discovers that a patient’s attitude toward keeping the disease in check will drive her individual needs for using the Web site. Newly diagnosed patients for the most part simply want any and all information related to their disease. They need to be able to select content relevant to their own problems. However, as patients come to grips with their sickness, their attitudes toward the disease tend to fall into one of three primary categories. For this pharmaceutical company, working with a set of diabetic patients, the needs groupings tend to look like this:

- Individualists. This type of patient relies on herself to make educated decisions on how to manage her disease. Individualists could be directed to online clinical support, and they could opt for customized electronic newsletters or for online health-tracking tools.

- Abdicators. This patient’s attitude toward the disease is one of resignation and detachment. She basically decides that she will “just have to live with the conditions of her disease,” so she ends up depending on the help given by a significant other. The site directs abdicators to various caregiver resources and provides planning information related to nutrition and meals.

- Connectors. This type of patient welcomes as much information and support as she can get from others to help her make educated decisions about how to manage her disease. The site directs connectors to online chat rooms and electronic bulletin boards where they can meet and converse with other patients. It has an “e-buddy” feature that pairs her up with a patient similar to herself.

For the pharmaceutical company to design a Web site that is truly customer-focused, it should try to figure out, for each returning visitor, what the particular mind-set of that visitor is, and then serve up the best features and benefits for that particular type of patient. The easier the enterprise can make it for different patients to find the support and assistance they need, individually, the more valuable those patients will become for the enterprise.

At this juncture, however, it is important once again to separate our thinking about the features and benefits of the Web site (i.e., the product, in this case) from the actual psychological needs and predispositions of the Web site visitors themselves. Any one of the visitors might in fact use any of the Web site’s many features on any particular visit. That means each of the Web site’s benefits will probably overlap several different types of customers, with different types of needs. But the customers themselves do not overlap—they are unique individuals, each with her own unique psychology and motivation. It is only our categorization of these unique and different customers into needs-based groups that might give us the illusion that they are the same. They may be similar in their needs, but at a deeper level, they are still uniquely individual, and this will be true no matter how many additional categories, or portfolios, we create. We simply categorize customers in order to better comprehend their differences by making generalizations about them.5

Healthcare Firms Care for and about Patient Needs

As much as any industry, healthcare could benefit from applying principles that address individual patients’ needs and values. In addition, relationships with donors and volunteers, medical staff, and suppliers would benefit from one-to-one Learning Relationships. But there are special challenges in this field.

Similar to any manufacturing enterprise, a health maintenance organization (HMO) can rank its patients by their value to the HMO. Interestingly, for an HMO, its most valuable patients are those it never hears from—those in good health.a However, the HMO does not want this group of customers to switch to another healthcare provider; it wants this set of valuable customers to use preventive healthcare procedures and to engage in a dialogue with its representatives so that they can understand each of its customers’ personal medical-related needs. The goal of a healthcare provider, therefore, could be to create an ongoing, interactive relationship with the customer-patient, a relationship that does not revolve around what happens between admission to the institution and discharge but rather between discharge and admission. That’s why many HMOs are engaged in building relationships by establishing contact with patients before an illness sets in, by inviting them to participate in reduced rates on exercise equipment, classes on smoking cessation, nutrition, and so on. These programs are win-win: They can contribute to the health and well-being of the patient or HMO member, and they help the HMO reduce costs through improved health of its patients.

Gary Adamson, who served as past president of Medimetrix/Unison Marketing in Denver, Colorado, said the power of healthcare integration lies in creating the ability to do things differently for each customer, not to do more of the same for all customers.b One of Medimetrix’s clients, Community Hospitals in Indianapolis, Indiana, for example, implemented “Patient-Focused Medicine,” a CRM initiative aimed at four constituent groups: patients, physicians, employees, and payers. The hospital has found that most medical practitioners customize the “care for you” component of healthcare by individually diagnosing and treating medical disorders. But Community also individualizes the “care about you” component—the part that makes most patients at most hospitals feel like one in a herd of cattle.

The hospital encourages thoughtful, high-level “service” by its doctors and nursing staff because it wants to show patients that they are being cared for; but the hospital also recognizes that random acts of kindness by a dedicated staff are not the same as customizing healthcare, which works only if the patient’s special needs are remembered and continued at the next shift and between visits.

The opportunity—and the challenge—for customization lies in caring about an individual patient’s needs. That means treating different patients differently in a cost-efficient and well-planned way. Healthcare, by its very nature, is among the most personal of any industry. Personal information provided to a doctor, hospital, pharmacy, or insurance company can be valuable to the organization but is highly private to the customer-patient. Healthcare personalization, of course, has existed for a long time, and certainly since the time when doctors made house calls and local druggists remembered each of their customers’ medical histories. The vast majority of healthcare services could benefit from a shift in focus from event treatment to patient relationships, for the good of the healthcare organization as well as the patient—perhaps starting with an integrated billing system that makes sense to patients and their caregivers.

Some companies in the healthcare industry already see personalization as a strategic advantage in a crowded marketplace. By adding Web-based services for its customers, Oxford Health Care, which offers health insurance in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, has provided the same level of personalized service a customer would get from a telephone call. Not only does the My Oxford program, a subsection of its Web site, allow customers to access their coverage plans and process claims, but Oxford Health Care has also fully invested in efficient, remote patient access services. Its Lifeline medical alert system connects patients with their Personal Response Associate at the push of a button; these associates can access personal information, contact the individual, and send appropriate help. Similarly, telemonitoring devices can gather vital signs and other health information daily from patients at home and transmit this information via phone line to Oxford HealthCare, where a nurse reviews it and responds according to parameters set by the patient’s physician.c

While reducing its cost to service “customers,” Oxford serves each customer better. But personalized online services go far beyond customized content or a listing of available healthcare products or services. The real opportunity lies in building a Learning Relationship between the healthcare provider and the customer. A drugstore, for example, might know a customer buys the same over-the-counter remedy every month. But if the same drugstore detects that the customer is suddenly buying the product every week, it could personalize its service by asking her whether she is having a health problem and how it could assist her with personal information or other types of medication. Already the pharmacy is the last resort for many patients to help spot possible drug interactions for prescription and over-the-counter drugs prescribed and recommended by a variety of different physicians. Using information to serve the customer better helps the drugstore create a long-lasting bond with this customer.

For instance, Medco, formerly part of Merck and a pharmacy benefits management company of Merck & Co., has created a sophisticated information system that links patients, pharmacists, and physicians, helping to ensure the appropriate use of medication for each individual based on his health profile. Merck-Medco customers are issued a pharmacy card that enables the company to identify customers when they fill and refill a prescription. But the company goes the extra step and shows that it not only cares for its customers but cares about them too. When a customer suddenly stops refilling a prescription, a Medco representative will likely contact him to see if he has forgotten to refill the prescription or if his health status has changed.

Personalization also lets healthcare providers focus their sales efforts on their most valuable customers. For example, Florida Hospital, which serves 1 million patients a year, provides a concierge service for patients that can track and automatically schedule routine appointments such as well-check visits and flu shots as well as referrals to specialists to help a patient avoid the usual three or four phone calls it takes to get the right person. Even in the hospital, patients can have an interactive experience with bedside kiosks, where they can access medical records and the Internet, purchase vitamins or medical supplies with a card swipe, or leave messages for physicians. “We’re really looking to bring value through coordination of care that is for the whole person,” says Des Cummings, executive vice president of Florida Hospital. “We’re looking at a whole person system for health and healing; caring for a person throughout their life.”d

aJaeun Shin and S. Moon, “HMO Plans, Self-Selection, and Utilization of Health Care Services,” Applied Economics 39 (2007): 2769–2784.

bDon Peppers, Martha Rogers, Ph.D., and Bob Dorf, The One to One Fieldbook (New York: Doubleday, 1999).

cAvailable at www.oxfordhealthcare.net, accessed April 27, 2010.

dMarji McClure, “Florida Hospital Prescribes a Personalization Cure,” 1to1 Magazine’s Weekly Digest, August 16, 2004, available at: www.1to1media.com/view.aspx? DocID=28465, accessed September 1, 2010.

Using Needs Differentiation to Build Customer Value

The scenarios of the toy manufacturer and the pharmaceutical company show how each had to be aware of its respective individual customer’s needs so it could act on them. Once a particular customer’s needs are known, the company is better able to put itself in the place of the customer and can offer the treatment that is best for that customer. Each company gets the information about customer needs primarily by interacting. Therefore, an open dialogue between the customer and the enterprise is critical for needs differentiation. Moreover, customer needs are complex and intricate enough that the more a customer interacts with an enterprise, the more learning an enterprise will gain about the particular preferences, desires, wants, and whims of that customer. Provided that the enterprise has the capability required to act on this more and more detailed customer insight, by treating the customer differently, it will be able to create a rich and enduring Learning Relationship.

A successful Learning Relationship with a customer is founded on changes in the enterprise’s behavior toward the customer based on the use of more in-depth knowledge about that particular customer. Knowing the individual customer’s needs is essential to nurturing the Learning Relationship. As the firm learns more about a customer, it compiles a gold mine of data that should, within the bounds of privacy protection, be made available to all those at the enterprise who interact with the customer. Kraft, for example, empowers its salespeople with the data they need to make intelligent recommendations to a retailer. (The retailer is Kraft’s most direct customer, and the retailer sells Kraft products to end-user consumers, who can also be considered Kraft’s customers.) Kraft has assembled a centralized information system that integrates data from three internal database sources. One database contains information about the individual stores that track purchases of consumers by category and price. Another database contains consumer demographics and buying-habit information at food stores nationwide. A third database, purchased from an outside vendor, has geodemographic data aligned by zip code.

Information is the raw material that is transformed into knowledge through its organization, analysis, and understanding. This knowledge then must be applied and managed in ways that best support investment decisions and resource deployment.

But truly to get to know a consumer through interactions directly with her, enterprises must do more than gather and analyze aggregated quantitative information. Accumulating information is only a first step in creating the knowledge needed to pursue a customer-centered strategy successfully. Information is the raw material that is transformed into knowledge through its organization, analysis, and understanding. This knowledge then must be applied and managed in ways that best support investment decisions and resource deployment.

Customer knowledge management is the effective leverage of information and experience in the acquisition, development, and retention of a profitable customer. Gathering superior customer knowledge without codifying and leveraging it across the enterprise results in missed opportunities.6

Scenario: Universities Differentiate Students’ Needs

Like more enterprises around the world, universities are building Learning Relationships with individual students as well as with the corporate concerns that are already providing much of the funding for tuition and research.

Higher education has a variety of different customers. Students, parents, employers, government, states, and donors are just some examples. Instead of measuring the success of a university by the number of students it enrolls, or even the cutoff point for admission, a customer-focused university gauges its success by the projected increase or decrease in a particular student’s expected future value. The university no longer focuses just on acquiring more students but on retaining existing learners and growing the business each gives the institution.

Interestingly, the fastest-growing sector of global higher education (and every university’s market is indeed global) is the for-profit university, which enrolls one-third of students worldwide. According to Sir John Daniel, a university administrator who has worked in Canada and the United Kingdom, a for-profit university offers three benefits to its students: efficiency, a focus on teaching students based on market demand rather than conducting research, and a focus on ensuring that its students succeed.a

Whether for-profit or public, academic universities want to attract and retain the most valuable customers and most growable customers (i.e., highly qualified, tuition-paying students) and to reap the most benefit from them, not just over their four years of study but over their many years as alumni as well. In order to integrate the typically siloed information on recruitment, retention, and development, higher-education spending on CRM will have seen a doubling from 2007 to 2012, reflecting universities’ increasing value of the 360-degree view of their customers.b

Acknowledging both actual and potential value of students and alumni is just as important. Higher levels of financial contribution coming from alumni are associated with higher income, but, most important, the degree of satisfaction with one’s undergraduate/graduate experience. Moreover, in many universities, each newly graduating class leaves behind a “Class Gift” that varies in expense and type. Some classes raise thousands of dollars to donate toward scholarships and loan funds; others raise money to help renovate university buildings that otherwise would have been left untouched. Retaining strong relationships with alumni is seen as beneficial not only for financial purposes; they also play other critical roles for the academic university—returning to teach, counseling graduate students, or serving on advisory boards to the university.

As more universities consider their options for achieving those goals, attention often turns to alumni as the answer. Institutions of higher learning have understood that prolonging relationships with alumni can improve the accuracy of the fundraising list, which in turn improves fundraising response rates and donor lifetime value. The number of schools that are implementing strategies for those purposes is increasing.

Because it is now possible to keep track of relationships with individual students, the size of a university is becoming a less potent competitive advantage. A university of any size has the opportunity to use information about each student to secure more of that individual’s participation. Notwithstanding the “brand” or status value of a handful of high-status Ivy League and top-ranked higher education institutions, securing and keeping the participation of more students will likely depend on who has and uses the most information about a specific student, not on who has the most students.

To compete, the customer-focused university has to integrate its entire range of business functions around satisfying the individual needs of each individual student. The school’s organizational structure itself will have to be altered, and it must embrace significant change, affecting virtually every department, division, administrator, and employee. Once it has migrated to a customer-strategy model, the university will be able to generate unprecedented levels of participant loyalty by offering an unprecedented level of customization and relationship building.

Student-customer valuation will require measures of success based on individual student results, not just product or program measures. Rather than seeing whether enough students enrolled in a particular course to justify its existence, for instance, the institution will also predict whether a particular student is valuable enough to justify a certain level of expenditure.

The customer-focused university will be able to calculate share of student on an individual, participant-by-participant basis, with the goal of capturing a greater share of dollars, time, and other investment in learning. The customer-focused university builds a Learning Relationship with each student by interacting over time and continuing to increase its level of relevance to each student by understanding her motivation. Although participation in the university should be motivation enough, the customer-focused university will understand whether a student is, for example, taking a course because of interest in the material, admiration for the professor, a need to be respected, a desire to make business contacts, as part of a degree program, career participation, or some other reason. Remembering what each student wants and finding ways to make the collaboration effort valuable to the participant leads to mass-customizing the offering, the response, the dialogue process, the level of recognition, the opportunity for active participation, and so on.

The implications of more cost-efficient electronic interaction for higher education are immense. Many universities are pioneers in adopting a customer strategy to develop Learning Relationships with each of their students. Western Governor’s University in Salt Lake City, Utah, is creating independent measurements of “output”—their graduates. In addition to traditional assessment of learning outcomes, such as those required by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB)—measuring the university’s quality by the number of doctorates on the faculty or books in the library—the school also is rating the academic performance of its students against an objective measure of the student’s overall accomplishment. The nation’s first online competency-based university, Western Governor’s University received the United States Distance Learning Association’s 2008 International Distance Learning Awards in two categories: the 21st Century Award for Best Practices in Distance Learning and Outstanding Leadership by an Individual in the Field of Distance Learning.c

Franklin University, an independent nonprofit institution serving 11,000 students in Columbus, Ohio, created a new position, Student Services Associate (SSA), designed to be the “customer manager” for its students. Each of the university’s 25 SSAs is evaluated and paid based on how many of his or her students make it to graduation. Every SSA interaction with a student is captured on the computer so that anyone interacting with the student can view his or her complete profile and history. In addition, to better meet the needs of busy students, the university became part of a Community College Alliance and now offers 24 undergraduate majors and 2 graduate programs entirely online. For Franklin, customer-focused strategies—led originally by past-university president Paul Otte and now by current president Dr. David R. Decker—have translated directly into revenue increases and greater share of student. In the mid-1990s, 60 percent of students were freshmen and sophomores; now 60 percent are juniors and seniors, another 10 to 12 percent are continuing on to graduate school, and surveys indicate higher levels of student satisfaction.d

Students at the University of Phoenix (UP), Arizona, are often underwhelmed at its physical facilities, but they enthusiastically participate in the school’s accredited programs in business, nursing, and education because they can get the learning they want and need on their own terms, according to their own schedules. UP draws “working students” who do not want to put their lives on hold to earn their degrees, so their courses last only five or six weeks and can be started virtually anytime.e Similarly, Boston University, whose online Bachelor of Liberal Studies degree ranks first among online teaching institutions, is reaching out to this working student population, aiming to provide a high-quality but flexible degree program that can fit in busy adult schedules.f

According to Arthur Levine, the president and professor of Teachers College, Columbia University, current demographic shifts will push colleges to choose a target audience to meet the various needs in the market. The fastest-growing student segment in the United States—women over the age of 25 who are attending part time and working—want the cost-effective, à la carte educational experience and don’t want to pay for a giant athletic facility they are not using. Simultaneously, the traditional 18- to 22-year olds who attend full time and live on campus (or nearby) want the widest possible course offerings and food options and expect student activities 24 hours a day. It is indeed not easy to serve a population of two opposite poles, those who want the bare minimum and the other half who want everything. So colleges face a challenge to decide whom they will serve and how, coming up with the ideal solution of reconsidering their mission and being able to accommodate different expectations under the same roof.g

To draw alumni in and keep the relationships going, academic institutions are building peer-to-peer communities on their Web sites that foster involvement and camaraderie. Free services include a lifelong university-branded e-mail address, searchable alumni directories, and customizable Web pages. For some institutions, the central focus of their Web community is the alumni database; others take a portal approach, using diverse content as the core property. Most universities hope that alumni will set the school’s Web portal as their default Web browser home page.

aSir John Daniel, “The Fastest Growing Sector of Higher Education,” convocation speech, University Canada West, November 22, 2008, available at: www.col.org/RESOURCES/ SPEECHES/2008PRESENTATIONS/Pages/2008-11-22.aspx, accessed September 1, 2010.

bChristopher Musico, “Making CRM Mandatory for University Administration,” Customer Relationship Management 12, no. 8 (2008): 20.

c“USDLA Recognizes Western Governors University with Two Major Distance Learning Awards,” press release, April 23, 2008, available at: www.wgu.edu/about_WGU/ usdla_awards_4-23-08, accessed September 1, 2010.

d2009–2010 Franklin University Academic Bulletin, available at www.franklin.edu.

eAvailable at http://university.phoenix.edu/, accessed April 29, 2010.

f“2009 Rankings of Online Colleges and Online Universities,” Guide to Online Schools, available at: www.guidetoonlineschools.com/online-colleges, accessed April 29, 2010.

gKarla Hignite, “Insights: Arthur Levine’s Call for Clarity,” Business Officer (May 2006), available at: www.nacubo.org/Business_Officer_Magazine/Magazine_Archives/May_2006/ Arthur_Levines_Call_for_Clarity.html, accessed April 29, 2010.

Summary

We have now discussed the necessity of knowing who the customer is (identifying) and knowing how the customer is different individually (valuation and needs). Getting this information implies that the enterprise will need to interact with each customer to understand each one better. Once the enterprise has ranked customers by their value to the enterprise and differentiated them based on their needs, it conducts an ongoing, collaborative dialogue with each customer. This interaction helps the enterprise to learn more about the customer, as the customer provides feedback about her needs. The enterprise can then use the customer’s feedback to modify its service and products to meet her needs (i.e., to “customize” some aspect of the customer’s treatment to the needs of that particular customer).

The “identify” and “differentiate” steps in the Identify-Differentiate-Interact-Customize (IDIC) taxonomy for developing and managing customer relationships can be accomplished by an enterprise largely with no actual participation by the customer. That is, a customer won’t necessarily have to know or involve herself in the process that the enterprise uses to identify her, as a customer, or to rank her by value, or even to evaluate her needs, as a customer. These first two steps—“identify” and “differentiate”—can be thought of as the “customer insight” phase of relationship management. However, the third step—“interact”—requires the customer’s participation. Interaction and customization can only really take place with the customer’s direct involvement. These latter two steps could be thought of as managing the “customer experience,” based on the insight developed.

Interacting with customers, the third step in the IDIC taxonomy, is our next point of discussion.

Food for Thought

1. Why has more progress been made on customer value differentiation than on customer needs differentiation?

2. If it could only do one, is it more likely that a customer-oriented company would rank all of its customers differentiated by value or differentiate all of its customers by need?

3. Is it possible to meet individual needs? Is it feasible? Describe three examples where doing this has been profitable.

4. For each of the listed product categories, name a branded example, then hypothesize about how you might categorize customers by their different needs, in the same way our sample toy company and pharmaceutical company did. Unless noted for you, you can choose whether the brand is business to consumer (B2C) or B2B:

- Automobiles (consumer)

- Automobiles (B2B, i.e., fleet usage)

- Air transportation

- Cosmetics

- Computer software (B2B)

- Pet food

- Refrigerators

- Pneumatic valves

- Hotel rooms

Glossary

Attributes Physical features of the product.

Benefits Advantages that customers get from using the product. Not to be confused with needs, as different customers will get different advantages from the same product.

Customer portfolio A group of similar customers. The customer-focused enterprise will design different treatments for different portfolios of customers.

Market segment A group of customers who share a common attribute. Product benefits are targeted to the market segments thought most likely to desire the benefit.

Needs What a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, synonymous with what she wants, prefers, or would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but in each case we are still talking, generically, about the customer’s needs.

1. In the view of some, differentiating by value first, then needs, may appear to focus first on the company’s needs, then those of the customers; but another way to look at this order of strategic imperatives is to think about how a company that used to treat every customer’s needs as equally important will now focus more on the needs of those customers who contribute the most to the success of the firm and therefore will put the needs of some customers ahead of the needs of other customers, thus allocating resources best for the most valuable customers.

2. A large body of academic research, as well as trade articles and professional work, has been published on the topics of benefits, attributes, and needs as well as the findings about the different reasons two customers with the same transaction history are motivated to buy the same products.

3. And the financial dimension is not limited to for-profits: For nonprofit organizations, the financial dimension might include maximizing funds from outside sources or maintaining fiscal stability. See Michael Martello, John G. Watson, and Michael J. Fischer, “Implementing a Balanced Scorecard in a Not-for-Profit Organization,” Journal of Business and Economics Research 6, no. 9 (September 2008): 68. For nonprofits, “customer” or member, or donor, or volunteer value may include proxies for financial value such as willingness to participate, compliance rates, voting record, donations of time and volunteerism, and so forth.