Chapter 7

Interacting with Customers: Customer Collaboration Strategy

Most conversations are simply monologues delivered in the presence of witnesses.

—Margaret Millar

So far, we have discussed the ways an enterprise can identify and differentiate customers. Both of these efforts help the enterprise prepare to treat different customers differently. But, essentially, both “identify” and “differentiate” are analytical tasks. They are at the heart of the efforts, working behind the scenes to gather information about a customer, to rank him by his value to the company and to differentiate his needs accordingly. These tasks aren’t really visible to a customer. In this chapter, we introduce a part of the Interact-Differentiate-Interact-Customize (IDIC) implementation methodology that gets the customer directly involved: interaction. We will see different viewpoints on the broad and growing emphasis on interaction with customers. But even as the discussion touches on the general and the particular, the main reason for interaction remains the same: to get more information directly from a customer in order to serve him in a way no competitor can who doesn’t have the information.

Managing individual customer relationships is a difficult, ongoing process that evolves as the customer and the enterprise deepen their awareness of and involvement with each other. To reach this new plateau of intimacy, the enterprise must get as close to the customer as it can. It must be able to understand the customer in ways that no competitor does. The only viable method of getting to know an individual, to understand him, and to get information about him is to interact with him—one to one.

In Chapter 2, we began to define a relationship, and provided a foundation for relationship theory. We listed several important characteristics in our definition of the term relationship; but one of the most fundamental of these characteristics is interaction. A relationship, by its very definition, is characterized by two-way communication between the two parties to the relationship.

Interacting with customers acquires a new importance for a customer-strategy enterprise—an enterprise aimed at creating and cultivating relationships with individual customers. The enterprise is no longer merely talking to a customer during a transaction and then waiting (or hoping) the customer will return again to buy. For the customer-strategy enterprise, interacting with individual customers becomes a mutually beneficial experience. The enterprise learns about the customer so it can understand his value to the enterprise and his individual needs. But in a relationship the customer learns, too—about becoming a more proficient consumer or purchasing agent for a business. The interaction, in essence, is now a collaboration in which the enterprise and the customer work together to make this transaction, and each successive one, more beneficial for both. The focus shifts from a one-way message or a one-time sale to a continuous, iterative process, which de facto moves both customer and enterprise from a transactional approach to a relationship approach. The goal of the process is to be more and more satisfying for the customer, as the enterprise’s Learning Relationship with that customer improves. The result of this collaboration, if it is to be successful, is that both the customer and the enterprise will benefit and want to continue to work together. This is no longer about generating messages about your organization. This is about generating feedback, creating a collaborative feedback loop with each customer by treating her in a way that the customer herself has specified during the interaction.

This is no longer about generating messages about your organization. This is about generating feedback.

Interacting with an individual customer enables an enterprise to become both an expert on its business and an expert on each of its customers. It comes to know more and more about a customer so that eventually it can predict what the customer will need next and where and how he will want it. Like a good servant of a previous century, the enterprise becomes indispensable.

Customer-strategy enterprises ensure that each customer gets exactly what he needs, no matter what, and this priority should extend from the front line all the way to upper management. Years ago, Southwest Airlines created a high-level position to coordinate all proactive customer communications—from the information sent to front-line representatives when flights are delayed, to personally sending letters and vouchers to customers thus inconvenienced. All the while, when the inevitable delay does occur, Southwest flight attendants and even pilots walk the aisles to update passengers and answer questions, conveying genuine concern in the moment. For a company to be truly customer-centric, interaction must happen at all levels, so as many employees as possible know what it feels like to be a customer.1

In this chapter, we show how a customer-strategy enterprise interacts with its customers in order to generate and use individual feedback from each customer to strengthen and deepen its relationship with that customer. This two-way communication can best be referred to as a dialogue, which serves to inform the relationship.

Dialogue Requirements

An enterprise should meet six criteria before it can be considered engaged in a genuine dialogue with an individual customer:

1. Parties at both ends have been clearly identified. The enterprise knows who the customer is, if he has shopped there before, what he has bought, and other characteristics about him. The customer, too, knows which enterprise he’s doing business with.

2. All parties in the dialogue must be able to participate in it. Each party should have the means to communicate with the other. Until the arrival of cost-efficient interactive technologies, and especially the World Wide Web, most marketing-oriented interactions with customers were prohibitively costly.

3. All parties to a dialogue must want to participate in it. The subject of a dialogue must be of interest to the customer as well as to the enterprise.

4. Dialogues can be controlled by anyone in the exchange. A dialogue involves mutuality, and as a mutual exchange of information and points of view, it might go in any direction that either party chooses for it. This is in contrast to, say, advertising, which is under the complete control of the advertiser. Companies that engage their customers in dialogues, in other words, must be prepared for many different outcomes.

5. A dialogue with an individual customer will change an enterprise’s behavior toward that individual and change that individual’s behavior toward the enterprise. An enterprise should begin to engage in a dialogue with a customer only if it can alter its future course of action in some way as a result of the dialogue.

6. A dialogue should pick up where it last left off. This is what gives a relationship its “context” and what can cement the customer’s loyalty. If prior communication between the enterprise and the customer has occurred, it should continue seamlessly, as if it had never ended.2

Implicit and Explicit Bargains

Conducting a dialogue with a customer is having an exchange of thoughts; it’s a form of mental collaboration. It might mean handling a customer inquiry or gathering background information on the customer. But that is only the beginning. Many customers are simply not willing to converse with enterprises. And rare is the customer who admits that she enjoys receiving an unsolicited sales pitch or telemarketing phone call. For an enterprise to engage a customer in a productive, mutually beneficial dialogue, it must conduct interesting conversations with an individual customer, on his terms, learning a little at a time, instead of trying to sell more products every time it converses with him.

If the customer-strategy enterprise is to remain a dependable collaborator with its customers, then it must not adopt a self-oriented attitude (see Chapter 2, “Thinking about Relationship Theory” and “CRM: The Customer’s View,” both of which emphasize the importance to the enterprise of not being self-oriented in its approach to customer relationships). Instead of sales-oriented commercials and interruptive, product-oriented marketing messages, the customer-strategy enterprise will use interactive technologies to provide something of value to the customer. By providing this value, the enterprise is inviting the customer to begin and sustain a dialogue. The resulting feedback increases the scope of the customer relationship, which is critical to increasing the enterprise’s share of that customer’s business.

To understand how radical this idea is, think about television. When advertisers sponsor a television program, they are in effect making an implicit bargain with viewers: “Watch our ad and see the show for free.” During television’s early decades, these implicit bargains made a lot of sense, because viewers had only a few other channels to choose from and no remote control to make it easy to change the channel. In the early days, everybody watched commercials.

But today’s television viewer lives in a vastly different environment. Not only are there hundreds of channels from which to choose, but people are also watching television more selectively, with instant—and constant—control. Audiences have the power to tune out commercials at their will or even to block out the advertisements altogether. And video delivered via broadband connections through the Web soon likely will overwhelm the traditional broadcast model entirely, as more and more consumers will be downloading full-length movies and television programs the way they currently download YouTube videos and then wirelessly pushing them to their large-screen television monitors for viewing. These technological trends are inevitable, driven not just by innovation but by intense consumer demand for choice and immediacy. The problem for marketers, therefore, is that, because the broadcast television medium is nonaddressable and noninteractive,3 there is no real way to tie the particular consumer who watches the television show back to the ad or to know whether she saw it in the first place. There is also no real incentive, usually, for the consumer even to watch the ad.

However, interactive communications technologies are two-way and individually addressable. Because of these attributes, interactive media equip marketers with the tools to make “explicit” bargains rather than “implicit” ones with their consumers. They can interact, one to one, directly with their individual media customers. An explicit bargain is, in effect, a “deal” that an enterprise makes with an individual to secure the individual’s time, attention, or feedback. Dialogue and interaction have such important roles to play, in terms of improving and enhancing a relationship, that often it is useful for an enterprise actually to “compensate” customers, in the form of discounts, rebates, or free services, in exchange for the customer participating in a dialogue.

The interactive world is chock full of examples of explicit bargains. Hundreds of Web site operators around the globe, from Hotmail to Yahoo!, offer free e-mail to customers who are agreeable to receiving advertising messages or facilitating the delivery of ad messages to others. Some of the ads are highly targeted, and even based on the content of the e-mail messages themselves. For example, if a Google Gmail user writes a personal message to a friend discussing, say, a trip to the Bahamas, Google will likely show banner ads on the e-mail page that promote air travel, vacation packages, or hotels. Marketers routinely buy “keywords” from search engines like Google, Yahoo!, Bing, and others, so that when a consumer uses one of these engines to search for, say, “flat screen televisions,” the marketer’s own ad will appear prominently within the search results. It is standard practice for a Web site operator to require a visitor to register, providing personal identifying data and preferences, in return for gaining access to the site’s more detailed information or automated tools.

Do Consumers Really Want One-to-One Marketing?

A New York Times articlea raised serious issues about the viability of one-to-one marketing. Citing a survey of consumer attitudes commissioned by professors at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Berkeley, the article reported that a clear majority of Americans (66 percent) reject the whole idea of tailored ads and personalized news, even without being told how their own interests are being tracked online.

But this survey is deeply flawed, and its authors’ conclusions are biased (they’re professors, they should know better!). This would be an irrelevant nonissue, not worth our time and trouble (or yours), except for the possibility that a survey like this could inflame public opinion enough to encourage some sort of ham-handed government regulation of online advertising and marketing. Other bloggers are already worried about this.

The survey was conducted by telephone. A thousand adult Americans were interviewed, and each interview began with three basic questions, asked in a random rotation:

1. Please tell me whether or not you want the Web sites you visit to show you ads that are tailored to your interests.

2. Please tell me whether or not you want the Web sites you visit to give you discounts that are tailored to your interests.

3. Please tell me whether or not you want the Web sites you visit to show you news that is tailored to your interests.

The problems with this survey should be obvious: First, people really don’t like advertising and marketing messages in general. (Is that a surprise to anyone?) Of course they don’t want tailored advertising, but they don’t want untailored advertising either. Consumers are, in general, suspicious of marketers’ motives and hostile to being “sold” things. But that doesn’t mean they reject personalization. They reject all the loud, interruptive messaging out there, ceaselessly clamoring for their attention span.

Second, these questions present no alternative. If the authors are going to conclude that consumers prefer not to have tailored ads, they have to say what they prefer instead. The only way to understand consumer preference is to compare consumers’ desire for one thing relative to their desire for something else. That’s part of the very definition of the word preference. However, doing that would have required a question such as:

Please tell me whether you would prefer the Web sites you visit to show you ads tailored to your interests or, instead, to charge you a small fee for viewing the Web sites.

And of course we all know what the answer to that question would be. You don’t need a survey to demonstrate it, because the history of the Web already makes it very clear that free, ad-supported content will triumph over paid content at least 90 percent of the time.

But third, any rookie market researcher can tell you that consumers who are asked generalized questions like this often have difficulty visualizing the actual situation. The right way to have asked this question would have been to demonstrate it to the consumer directly. For instance, prior to asking these questions, what if the interviewer had first asked:

Please tell me whether you prefer diet drinks or nondiet drinks.

And then they could ask:

Please tell me whether you would prefer the Web sites you visit to show you ads for diet drinks or for nondiet drinks? (Pick one.)

There is still, however, a very important lesson to be drawn from this survey: the fact that consumers don’t see any benefit to tailoring is an indictment of most of us marketers, because we have done such a lame job of tailoring our messages and making them genuinely relevant to our customers. It is not surprising that ordinary consumers would have difficulty visualizing personalized advertising messages, because even today, with all the computer power and interactive technologies available to marketers, most consumers have very rarely witnessed personalized ads that are genuinely relevant!

Source: Based on blog post by Don Peppers, “Do Consumers Really Want One-to-One Marketing?” October 21, 2009, available at: www.1to1media.com/weblog/2009/10/do_consumers_really_want_one-t.html#more, accessed September 1, 2010.

aStephanie Clifford, “Two-Thirds of Americans Object to Online Tracking,” New York Times, September 29, 2009, available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/09/30/business/media/30adco.html?_r=3&partner=rss&emc=rss, accessed September 1, 2010.

Explicit bargains with consumers are certainly not confined to the Web either. More than one mobile phone company has been launched based on the idea of offering free voice minutes and text messaging in return for accepting advertising messages and responding to marketing offers.

In an interactive medium, an advertiser can secure a consumer’s actual permission and agreement, individually. By making personal preference information a part of this bargain, the service can also ensure that the ads or promotions delivered to a particular subscriber are more personally relevant, in effect increasing the value of the interaction to the marketer by increasing its relevance to the consumer. Explicit bargains like this are good examples of what author Seth Godin calls “permission marketing” (a concept we discuss in more detail in Chapter 9) in which a customer has agreed, or given permission, to receive personalized messages.

Two-Way, Addressable Media: A Sampling

In contrast to the one-way media that characterized mass marketing, the future of customer relationships will be interactive. Not “I talk, you listen” but “You talk, I listen,” and vice versa, and “We all talk, and everybody can listen in.” Likewise, more and more media are “addressable.” That means I can send a particular message to a particular individual at a known “address,” whether that address is a geographic address on a street, or an e-mail address, or Facebook account, or telephone number, or text address, or a combination of these and other new interactive, addressable media available every day.

- World Wide Web. The Web has become one of the most effective media to engage a customer in an individual interaction. An enterprise’s Web site is a highly customizable platform for collaborating with customers and learning about their individual needs effectively and inexpensively. (We talk more about the Web as a venue for customization in Chapter 10.)

- Social media. While technically just one aspect of the World Wide Web, the Web sites and online services that have been constructed to allow people simply to create content for other people and to share conversations and comments with others who have similar or intersecting interests—sites such as Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, and LinkedIn—represent a major change in how consumers acquire information and interact with their environments. The social media phenomenon is complex and rich enough all by itself to require a customer-strategy enterprise to plan deliberate strategies for dealing with social media, in an effort to build and strengthen its customer relationships.

- Wireless. The increasing proliferation of wireless technology is promising to “unhook” people from the network of cables and wires that used to connect them to the ground, freeing them not just to surf the Web using their iPhones, BlackBerries, and other smart phones but to connect their devices wirelessly to the Internet in coffeeshops, hamburger outlets, universities, airliners, and even many major cities, where ubiquitous WiFi technology has been installed for everybody. It is becoming clear that in the twenty-first century, not just in developed countries but across the whole world, people are going to be connected to the network and able to interact electronically with companies and other people more often than they will be offline. (Indeed, the very term online has now been rendered an archaic usage, much like “dialing” a phone number. Both terms will mystify our grandchildren as much as the word typewriter will.)

- Voicemail. Enterprises have established voicemail systems for their customers that enable them to phone in a question or comment and leave a message. Voicemail has many different potential dialogue applications.

- E-mail. Enterprises are using e-mail to write personalized messages to customers about their latest product offerings, sales promotions, customer inquiries, and many other important topics (we discuss more about e-mail later in this chapter).

- Texting (SMS—Short Message Service) and instant messaging (IM). Texting from a mobile phone and using the instant messaging feature of various e-mail and online services is another mechanism for quick, highly efficient interactions. Although it’s a more common business practice outside the United States, marketers can incorporate text-back codes to encourage customers to interact with them wherever they are, at any time—because everyone always has their mobile phone with them. Always.

- Fax. Fax machines are a highly interactive medium. The customer can fax an order to the enterprise. Or the enterprise can use a fax-on-demand service to enable customers to request product or service information via their fax machines. The enterprise also can fax customized catalogs, product information sheets, newsletters, and other documents to the customer on request. Fax also makes it easy to reach those who do not have online capability.

- Digital video recorders. The digital recording device, such as TiVo and others like it, has revolutionized television by enabling audiences to create highly personalized TV-viewing experiences. Digital video recorders (DVRs) are also changing television advertising. Instead of bombarding viewers with commercials that are not relevant, advertisers now have the opportunity to personalize their messages. Knowing the viewers’ demographics and viewing preferences, advertisers will be better able to match their ads to the right people.

- Interactive voice response. Now a feature at most call centers, interactive voice response (IVR) software provides instructions for callers to “push one to check your current balance, push two to transfer funds,” and so forth. One frequent problem with IVRs is that companies tend to use them more to reduce their costs than to improve their service, with the result that customers often are frustrated if the choice they want is not offered or if it becomes difficult to contact a “live” human.

- More new media every week. No print listing can keep up with the myriad of ways popular and esoteric that people of different generations and technical expertise will use and adapt to connect with each other and the companies they do business with.

Technology of Interaction Requires Integrating across the Entire Enterprise

Most business-to-business (B2B) companies already have active sales forces engaged in some form of relationship building with the accounts they serve, but new technologies allow them to automate a sales force to better ensure that customer interactions are coordinated among different players within an account and that the records of these interactions are captured electronically. For a business-to-consumer (B2C) company, however, interactive technologies enable it to create a consumer-accessible Web site, and to coordinate the interactions that take place on this Web site with the interactions that take place at the call center and at the point of sale and at any other point of contact with the customer. The universal question for such an enterprise, wrestling with how to use these technologies, is: What is the right communication or offer for this particular customer, interacting with us at this time, using this technology?

The point is that the arrival of cost-efficient interactive technologies has pretty much forced companies in all industries, all over the world, to take a step back and reconsider their business processes entirely. To deal with interactivity, they must create new processes that are oriented around the coordination of all these newly possible customer interactions. And they must ensure that the interactions themselves not only run efficiently but are effective at building more solid, profitable relationships with customers.

Don Schultz, Stanley Tannenbaum, and Robert Lauterborn’s classic book, The New Marketing Paradigm: Integrated Marketing Communications,4 documented the problems that occur whenever a single customer ends up seeing a mishmash of uncoordinated advertising commercials, direct-mail campaigns, invoices, and policy documents, and made the case for consistent marketing communications across the entire enterprise. Today, sophisticated interactive technologies enable enterprises to ensure that their customer-contact personnel can remember an individual customer and his preferences. A company can use software that creates an “ecosystem” of data about its customers and cull information from all of the touchpoints where it interacts with customers—call centers, Web sites, e-mail, and other places. If the enterprise can better understand its customers, it can better serve them by providing individually tailored offers or promotions and more insightful customer service.5 The result is that integrating the enterprise’s marketing communications is no longer a cutting-edge strategy but a must-have standard.

For this reason, the enterprise has to integrate all of its customer-directed communication channels so that it can accurately identify each customer no matter how an individual customer or a customer company contacts the enterprise. If a customer called two weeks ago to order a product and then sent an e-mail yesterday to inquire about his order status, the enterprise should be able to provide an accurate response for the customer quickly and efficiently. The company should remember more about the customer with each successive interaction. More important, as we said before, it should never have to ask a customer the same question more than once, because it has a 360-degree view of the customer, and “remembers” the customer’s feedback across the organization. The more the enterprise remembers about a customer, the more unrewarding it becomes to the customer to defect. The customer-strategy enterprise ensures that its interactive, broadcast, and print messages are not just laterally coordinated across various media, such as television, print, sales promotion, e-mail, and direct mail, but that its communications with every customer are longitudinally coordinated, over the life of that individual customer’s relationship with the firm.

Providing any kind of dialogue tool to customers enables the enterprise to secure deeper, more profitable, and less competitively vulnerable relationships with each of them. The deeper each relationship becomes, and the more it is based on dialogue, the less regimented that relationship will be. The customer may want to expand the dialogue on his own volition because he knows that each time he speaks to the enterprise, it will listen. Today, what most enterprises fail at is not the mechanics of interacting but the strategy of it—the substance and direction of customer interaction itself.

Today, what most enterprises fail at is not the mechanics of interacting but the strategy of it—the substance and direction of customer interaction itself.

Companies that employ such integration of customer data and coordination of customer interaction develop reputations as highly competent, service-oriented firms with excellent customer loyalty. Dell Computer has used direct mail, e-mail, personal contact by sales representatives, and special access to what amounts to intranet Web sites for large Dell accounts to stay connected with those customers.6 JetBlue’s reputation for service7 has been burnished by its extremely good online interaction efficiency and the seamless connections that customers experience among the airline’s reservations, ticketing, baggage tracking, and flight operations systems. Best Buy can use interactive connections to help customers analyze product features, track deliveries, and even solve technical problems by getting help from any one of several thousand company employees linked through Twitter into what the company calls its Twelp Force.8

Over time, a customer who interacts with a competent customer-strategy enterprise will come to feel that he is “known” by the enterprise. When he makes contact with the enterprise, that part of the organization—whether it is a call rep or a service counter or any other part of the firm—should have immediate access to his customer information, such as previous shipment dates, status of returns or credits, payment information, and details about the last discussion. A customer does not necessarily want to receive more information from the enterprise; rather he wants to receive better, more focused information—information that is relevant to him, individually.

Integrating the interactions with a customer across an entire enterprise requires the enterprise to develop a solid understanding of all the points at which a customer “touches” the firm. Stated another way, the customer-strategy enterprise needs to be able to see itself through the eyes of its customers, recognizing that those customers will be experiencing the enterprise in a variety of different situations, through different media, dealing with different systems, and using different technologies. Mapping out these touchpoints is one of the first tasks many customer-strategy enterprises choose to undertake, and one comprehensive process for accomplishing the task is outlined in the next section by Mounir Ariss, a managing partner at Peppers & Rogers Group.

Touchpoint Mapping

Mounir Ariss

Managing Partner, Middle East, Peppers & Rogers Group

Our goal is to help client companies do a better job of managing the experiences their customers have, by using customer insight to fashion better, more convenient, and more personalized relationships with these customers individually. A customer’s experience with a brand or an enterprise can be thought of as occurring in three different dimensions:

- Physical. Pertaining to the design of physical locations such as stores, sales and service offices, bank branches, and so forth, the physical dimension includes not just the location itself but factors such as the availability of parking space, pedestrian accessibility, interior design, and even the smoothness of flow of customers within the premises.

- Emotional. Harder to pin down, but highly important to the customer experience, the emotional dimension is related to the culture of the customer-facing employees and their behaviors when interacting with a customer. More than once we’ve seen companies go through comprehensive business process reengineering (BPR) and automation and then fail when it comes to dealing with their customers due to a culture that is just not customer oriented. Culture-change programs, while challenging, can achieve results. The key is to create awareness and desire for change while enabling employees, measuring them, and providing constant feedback. A culture-change program could be as basic as training contact center employees on the 10 things never to say to a customer or on how to deal with difficult customers. Measurements feedback mechanisms could then be set up using mystery shopper programs.

- Logical. The “logical” issues at a company include the firm’s business processes, information flows, and technology components. This is often the first dimension of the customer experience addressed by enterprises trying to become more customer-centric. Understanding (and then modifying) its business processes is an important step any company must take in order to begin managing customer relationships in a more directed, beneficial way. And this is the dimension covered by a Customer Experience and Interaction Touchmap.a

Within the IDIC framework, “identify” and “differentiate” are purely internal steps to a company. They could be done without the customer knowing about them. However, “interact” and “customize,” as the names indicate, are external steps where a company is actually managing the customer’s experience. Over the years, different companies have introduced tools to try to document the customer experience, diagnose gaps, and redesign it.

The Touchmap is a graphical depiction of the interactions a company has with each segment of its customers across each of the available channels. Its purpose is to take an outside-in view of customer interactions instead of the traditional inside-out view typically taken in BPR work. This approach is usually an eye-opener for organizations, and very often it is one of the rare times the customer perspective is actually brought to the attention of senior executives and explicitly considered in designing some interactions. For instance, more than once we have asked executives with a financial services client to go through the process of opening an account and then applying for a credit card at the enterprise where they themselves are employed. Many find just completing the application forms highly frustrating; some are amazed at how their customer-facing employees lack the information needed and even at the interpersonal skills required to deal with customers. Sources of frustration include not just the sheer volume of information being requested in an application form but also the fact that much of the requested information is already stored in the bank’s own systems, even though it is demanded from the customer anew, multiple times, in different application forms.

One useful way to think about this is to generate both a “Current State” Touchmap, to depict all the enterprise’s current interactions with customers and identify gap areas, and a “Future State” Touchmap, to depict the desired customer interactions—interactions that will be customized based on the needs and values of individual customers. Ideally, these Future State interactions should be a tool for a company to deliver on its brand promise and build customer value.

In addition to representing customer interactions from the customer’s own perspective, a Touchmap links these interactions with the enterprise’s internal processes, systems, and high-level information flows. This allows a company easily to identify organizational silos and broken processes, insufficient or nonexistent information sharing, poor system integration, and the general lack of cooperation among departments found at many companies. In our experience, most firms are already aware of many of the issues highlighted in a Current State Touchmap, but they probably never saw all of them illustrated at once, nor were they cognizant of how intricately these flaws and problems are related to each other and how seriously they inhibit a good customer experience.

Current State Touchmap

Preparing a Current State Touchmap for a company consists of several steps, all designed to ensure that the customer’s perspective is taken into consideration. In our consulting practice, we architect the process to meet the needs of the particular client and industry being served (telecom, e.g., has different issues from banking or government services), but in general, these tasks need to be accomplished to render a satisfactory and useful Touchmap:

- Recognition of different types of customers. Taking the customer’s point of view necessarily involves recognizing that different customers will have very different perspectives. The basic premise of CRM is “treating different customers differently,” so a Touchmap must accurately represent any customer-based differentiation within the same interaction. For a Current State Touchmap, these variations could be based, at least initially, on broadly defined segments—individual customers and business customers, for instance. Depending on the level of sophistication of a company, the Future State Touchmap could include variations based on a more granular segmentation or actual portfolio building. For example, most valuable customers (MVCs) could benefit from a totally different complaint-management process. Therefore, before starting a Touchmapping exercise, a company needs to identify its current customer groups and decide whether the current portfolio grouping or segmentation strategy will be sufficient for the customization of future interactions.

- Analysis of the customer life cycle. Broadly, a customer’s life cycle can be broken down into four principle parts: (1) awareness of a need, (2) decision to buy or contract with an enterprise to meet that need, (3) use of the product or service bought, and (4) support for the product and the ongoing relationship.

- High-level customer interviews. Customer interviews should allow us to identify a more granular breakdown of these four life-cycle steps and also will allow an enterprise to develop a better understanding of what the customer goes through, even before first interacting with the company. For example, how, where, and in what context did the customer become aware of a certain need? Was the customer talking to a friend? Did the customer have a promotion or a salary raise? Is the customer going through a change in life stage? What were the customer’s general perceptions about the company’s offering before starting to interact with the company? Did those perceptions change after the customer started interacting with the company or after buying a product or service? These customer interviews should be set up with a small sample of customers from each of the preidentified customer groups—typically 5 to 10 customers representing each group are sufficient for this stage.

- Customer satisfaction surveys. When available, satisfaction surveys can add some intelligence to the analysis of customer life cycle. A comprehensive survey, in fact, could minimize the need for and sometimes even replace customer interviews.

- Graphical illustration of customer life cycle. By linking customer feedback and comments from surveys and interviews to each stage of the life cycle, an initial diagnostic can be rendered, and a number of potential “quick wins” can almost always be identified—inadequate coordination of marketing materials or inaccurate transfer of information from the Web site, and so forth. After first illustrating a customer life cycle with each of its identified stages highlighted, we can then use callout boxes to document actual customer comments and color-code them (bad, neutral, and good) to pinpoint problematic areas visually. Often some of the underlying problems a company is facing in its customer interactions will be obvious from a color pattern that emerges. For example, if the early stages of a customer life cycle are in green, middle stages in yellow, and late stages in red, the company is probably performing really well in its marketing and sales functions but the high expectations it is setting for its products or services are not then being met. A more random distribution of good, neutral, and bad comments could be an indicator of inconsistencies in employee training, culture, and performance.

- Voice of customer. More detailed interviews with customers are now called for, in order to get at the actual details of what different customers go through at different states of the life cycle when interacting with the enterprise.

- Voice of employee. Detailed interviews of employees, emphasizing various business process owners, will allow the enterprise to link the customer’s perspective with the company’s own internal processes. Gaps between the two indicate potential improvement opportunities.

- Analysis of high-level information flows. It is important to identify critical data elements (CDEs) that facilitate decision making and process execution. During employee interviews with process owners, information should be compiled about which CDEs are captured or missing, updated consistently or out of date, disseminated effectively or stored in silos, utilized to generate customer insight or stored but not effectively used. Graphically, customer data that are not being captured in any system are highlighted with a “STOP” sign on the Current State Touchmap. Data being captured but not disseminated are highlighted with a “DEAD END” sign.

- Review of high-level technology components in use. Each of the processes illustrated in the Touchmap should be linked to supporting technology, when available. Once the technology components are identified and plotted at the center of the Touchmap, each of the processes can then be linked with the appropriate technology. The result will look something like a business process map for the enterprise, but rather than starting with business processes and mapping their effects, the Touchmap will start with customer interactions and map them in toward the business processes.

Future State Touchmap

The Future State Touchmap (see Exhibit 7A) should be drawn to depict how a redesigned set of customer interactions will function, once all improvement opportunities have been applied. Typical BPR work focuses on reducing the time it takes to complete an interaction or a process, and reducing the cost of completing it. BPR usually involves introducing quality controls to ensure time and cost efficiencies are achieved. The Future State Touchmap is designed to achieve these goals, but also to do a more complete and accurate job of taking the enterprise’s customer strategy into consideration. Therefore, when putting a Future State Touchmap together, it’s vital to incorporate a variety of “best practices” in managing customer relationships and experiences.

EXHIBIT 7A Future State Touchmap

While there are a large number of such best practices for relationship management (many of them covered in different chapters of this book), some examples would include:

- Treat different customers differently. Doing this usually will mean that different business processes have to be designed for the same type of interaction when it is applied to different customers or different customer groups. As a “best practice,” the first level of differentiation in business processes should be by customer value—for instance, treating MVCs to a more personalized service level based on their preferences. Working with one of the main telecommunication operators in the Middle East, for instance, we introduced four value tiers and designed different sales and service models for each of the tiers. Customers in the lower value tiers were driven toward remote self-service channels, but the high-value tiers were offered preferential treatments at all channels, assigned to the head of the queue at the contact center, receiving shorter complaint resolution times and shorter product installation times, and so forth.

- Unique customer identification at all touchpoints to identify customers. As just one example, many interactive voice response (IVR) systems in call centers request customers to enter their identification (ID) and personal ID number (PIN) before being directed to an agent. Then, when the customer finally talks to a human voice, often the first question the agent asks the customer is to repeat this identifying information.

- “Drip irrigation” techniques for collecting customer information. Rather than long application forms that request excessive information and often turn customers off, future-state interactions should focus on collecting less information at the beginning of a relationship with a customer but then enriching that information over time, as the relationship progresses.

- Never ask for the same information twice. Many companies request the same information from a customer over and over again. The future-state design would eliminate such occurrences to the extent possible, so the burden of repeating information falls on the company, not the customer.

Why Is a Touchmap Important?

The Customer Experience and Interaction Touchmap is a visual tool illustrating a strong link among customer groups, customer interactions, delivery channels, business processes, information flows, and technology components. It provides a holistic picture of how a company interacts with customers and sheds light on some of the burning issues affecting customer satisfaction, loyalty, retention, and growth.

Many companies are not fully aware of the services they offer and the multitude of channels they actually use. Others don’t have a standard definition of what a service is. For one of our recent clients, the number of different “customer services” reported to senior management varied between 12 and 200. This large variation was due to the fact that the company did not have a standard definition of what a service is. In addition, several departments in the company were allowed to offer services with no central coordination whatsoever. Through a Touchmapping project, this client was able to introduce standards in service definition, development, and deployment.

In a recent public sector project, we worked with a government in the Europe, Middle East, and Asia region to develop a full inventory of the services that each government department provides. As a part of this project, we introduced a standard way of defining government services. Two Touchmaps were produced, one covering citizen “customers” and the other covering business “customers.” The Touchmaps covered over 2,000 government services and resulted in a multiyear effort to enhance public service delivery in that country.

The Touchmap has also proven to be a versatile tool for a variety of other purposes related to managing customer relationships. Some of the uses we have seen over the past 15 years are:

- Technology implementation tracking. Some of the companies we have worked with have used monthly updates of the Touchmap to highlight their progress in CRM implementation and automation of business processes.

- Employee induction and training. Other companies have used a Touchmap to provide high-level training and orientation to employees, allowing them to better understand and visualize what the company does in general and how their jobs or tasks affect customers and the rest of the organization.

- Employee performance tracking. Some companies have added traffic light indicators next to each of the interactions illustrated on the Touchmap and linked quarterly customer satisfaction survey results to each of these indicators.

- Executive sponsorship. The visual display of complex information brought the topic closer to senior executives and helped secure more support and sponsorship for customer issues.

- Elimination of redundancies and other opportunities for efficiencies. Often a company realizes that different parts of the company each have the same good idea and each one has reinvented the wheel in trying to build customer relationships. A Touchmap contributes to a central repository for customer learning and methodology.

- Revealing data gaps and silos. A Touchmap exposes needs for particular data to be collected and to share data between and among parts of the organization to build a single view of the customer across the organization, without burdening the customer by asking for the same information more than once.

In summary, a Touchmap is an illustration of all interactions that happen between a company and its customers, based on the customer segments and depicted from the customer’s perspective. Its primary benefit is to enable the enterprise to maximize customer value by treating different customers differently.

aBased on 1to1SM Touchmap work conducted by Peppers & Rogers Group.

Customer Dialogue: A Unique and Valuable Asset

Interaction with a customer, whether it is facilitated by electronic technologies or not, requires the customer to participate actively. Interaction also has a direct impact on the customer, whose awareness of the interaction is an indispensable part of the process. Since interaction is visible to customers, interacting customers gain an impression of an enterprise interested in their feedback. It is a vital part of the customer experience with the brand or the enterprise. The overarching objective on the part of the enterprise should be to establish a dialogue with each customer that will generate customer insight—insight the enterprise can turn into a valuable business asset, because no other enterprise will be able to generate that insight without first engaging the customer in a similar dialogue.

This is one of the key benefits of the Learning Relationship we’ve been discussing, and it is based on the fact that different customers want and need different things. This means we also should expect different customers to prefer different interaction methods. One customer prefers mail to phone; another likes a combination of e-mail and regular mail; still another only visits social networking sites, such as Facebook. The level of personalization that the Web affords to a customer also should be available in more traditional “customer-facing” venues. Retail sales executives in the store, for instance, should have access to the same knowledge base of customer information and previous interactions and transactions with the enterprise as a customer service representative (CSR) at corporate headquarters or customer interaction centers. Enterprises must be able to identify which channels each of their customers prefer and then decide how they will support seamless interactions. Those enterprises that fail to provide these interaction capabilities can lose sales and compromise relationships.9

The goal is not understanding a market through a sample but to understand each individual in the population through dialogue.

The goal for the customer-strategy enterprise is not just to understand a market through a sample but also to understand each individual in the population through dialogue. The dialogue information that is of most interest to the enterprise falls into two general categories:

1. Customer needs. The best method for discovering what a customer wants is to interact with him directly. Each time he buys, the enterprise discovers more and more about how he likes to shop and what he prefers to buy. Interactions are important not only because the customer is investing in the relationship with the enterprise, but also because the enterprise learns substantive information about the customer that a competitor may not know. Interaction gives the enterprise valuable information about a customer that a competitor cannot act on.

2. Potential value. With every customer interaction, customers help the enterprise estimate more accurately their trajectory and their actual value to the enterprise. Getting a handle on a customer’s potential value, however, is often problematic. Through dialogue, a customer might reveal more specific plans or intentions regarding how much money she will spend with the enterprise or how long she will use its products and services. Insight into a customer’s potential value could include, among other things, advance word of an upcoming project or pending purchase; information with respect to the competitors a customer also deals with; or referrals to other customers that could be profitably solicited by the enterprise. This type of information is not usually available from a customer’s buying history or transactional records and can be obtained only through direct interaction and dialogue with the customer.

Customizing Online Communication

Tom Spitale

Principal, Impact Planning Group

“Nice product. Bad price. Let me go check the competition’s site.” Every chief executive in the world has felt the double-edged sword of online commerce. On one hand, the Internet boosts performance as the enterprise interacts with customers, suppliers, or channels at low costs. However, it has lowered the cost of entry for every competitor in the world. The Internet often is seen as the weapon of competitive choice for those only interested in competing on low price.

Executives at one healthcare insurer found a unique approach for using their Web site to block competition. The standard question in their industry is: How do we retain healthy customers who care very little about the features and benefits of our insurance policies? Your best customer, in this case, may be a 24-year-old man who runs three miles a day—and this dude is not likely to care much about insurance. If you run a health insurance company, you desperately want to hold on to such healthy customers, because the profit you derive from them will enable you to pay medical expenses for other insurance members who fall ill.

Lose enough healthy consumers and your entire company gets sick. A competitor with a lower price—even if it has a lousy offering—is likely to steal healthy customers away.

The executive team at this insurer decided to use its Web site to wrap a new layer of value around its core product of health insurance: customized health-related information. The company realized this was the best way to become relevant to its desired audience of physically fit consumers: Add communications and services that appeal to their healthy lifestyle, and customize the offers so they are relevant. Its Web site was the perfect vehicle, because while the firm couldn’t hire an army of customer relationship experts to offer personal communications to members, it could use dynamic content generation online to mass-customize the message.

To understand which services would be most appealing, the company cataloged wide-ranging content, including media publications tangentially related to health, and came up with innovative ideas. Fitness runners and weight lifters got unique information; cosmetics and baseball game information were added to the mix—all “expanding the need set”a of healthy consumers who previously didn’t care. This approach gave healthy customers reason to remain loyal (“My health insurer understands my preferences and provides personally relevant advice”) and reduced benefit costs by providing information that helped those with problems get better.

The lesson: Your Web site can block competitors by surrounding your core offering with a layer of personalized information and value. How would any company duplicate this insurer’s online communication customization in a different industry? Utilizing needs-based segmentation or portfolio-building in Web site design is key.

Needs-based segmentation (see Chapter 6) recognizes that different sets of customers have different needs. Filtering out content that is not relevant to each segment—and pointing people quickly to the most relevant content to them—is a valuable differentiator in a time-starved world.

This filtering can be done in a sophisticated fashion or very simply. Amazon.com has invested heavily in its Personal Recommendations strategy. In essence, it is creating a one-to-one relationship with each of its customers based on their individual ratings of books, and—wherever customers are willing to write a review—allowing customers to listen in on each other’s comments as well as benefit from ratings and usage. Many customers prefer to see comments from other people, even strangers, before they buy a product.

But what about a B2B company with a limited budget? A boutique strategy consulting firm with less than $5 million in annual revenues is using this concept in a much more straightforward, yet profitable, way. This firm recognizes that its customers approach strategic planning in different ways. For example, some companies enjoy rigor and discipline in their planning processes while others prefer to maintain some “entrepreneurial freedom” in their strategic planning.

The consulting company created a “front door” to its Web site that asks visitors to identify themselves based on one of four types of companies, according to their strategic planning profile. These four types of companies are really “needs-based segments” of firms. Once a visitor has chosen a profile, the Web site content is parsed to create a pathway to more relevant content. For example, the more entrepreneurial segment won’t see information on creating entire planning processes. Instead, they will be given information on “quick hit,” single-topic issues and see case studies about how other entrepreneurial companies are improving their strategic planning within a very fluid culture. The process-oriented segment will see still different content, offering free webinars on how to build strategic planning road maps or downloadable white papers on how to standardize planning presentations. They can read case studies on how process-oriented companies drive standardization throughout their organizations.

This is different from simply setting up different sections of a Web site with different types of offerings. Visit some B2B Web sites; very few, if any, will have a front door that customizes your pathway through the site.

And yet the financial return on site from this kind of interactive content customization is very high. Amazon.com is doing quite well, despite the fact that it doesn’t require a purchase in order to provide you with recommendations.

And there are other benefits as well. High percentages of new visitors to the Web site of the consulting firm just profiled reach out to the company through live channels to discuss doing business. A typical quote during that first live conversation? “You listen better than your competitors.” Do you think it has something to do with customized interactions on the Web site?

aRead more about the “expanded need set” in Chapter 10.

Because most customers will not sit still for extensive questioning at any given touchpoint, the successful customer-oriented enterprise will learn to use each interaction, whether initiated by the customer or the firm, to learn one more incremental thing that will help in growing share of customer (SOC) (see Chapter 1) with that customer. This is the concept we call drip irrigation dialogue. USAA Insurance in San Antonio, Texas, calls it “smart dialogue.” As the basis for intelligent interaction, USAA uses business rules within its customer data management effort to a make a customer’s immediate history available to its CSRs as soon as a customer calls. The CSRs also see a box on their computer screens that state the next question USAA needs to have answered about a customer in order to serve him better. This is not a question USAA is asking every customer who calls this month; it is the next question for this customer.

Golden Questions are designed to reveal important information about a customer while requiring the least possible effort from the customer.

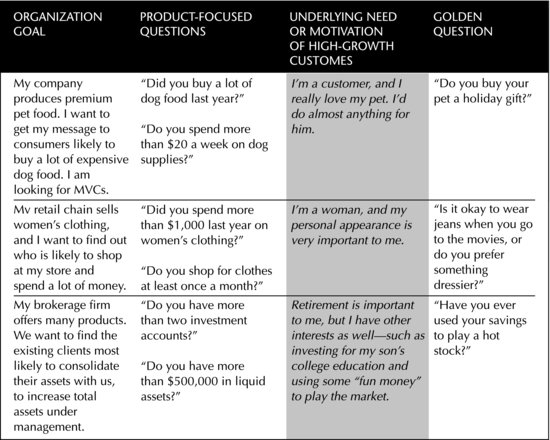

In many cases, an enterprise will use Golden Questions to understand its customers and thus achieve needs and value differentiation quickly and effectively (see Chapters 5 and 6). Golden Questions are designed to reveal important information about a customer while requiring the least possible effort from the customer. Designing a Golden Question almost always requires a good deal of imagination and creative judgment, but the question’s effectiveness is predetermined by statistically correlating the answers with actual customer characteristics or behavior, using predictive modeling. In general, an enterprise should avoid most product-focused questions, except in situations in which the customer is trying to specify a product or service, prior to purchase. Instead, the most productive type of customer interaction is that which reveals information about an individual customer’s underlying need or potential value. To better understand how product-focused questions differ from Golden Questions, examine the hypothetical chart in Exhibit 7.1

EXHIBIT 7.1 Development of Golden Questions

Not All Interactions Qualify as “Dialogue”

Many interactions with customers are simply not welcomed by the customer. In fact, a large portion of customer-initiated interactions with businesses occur because something has gone wrong with a product or service, and the customer needs to contact the enterprise to try to get things put right. It can be frustrating in the extreme for a customer to try to navigate through a complex IVR in order to get a problem resolved. One of the best books on managing contact-center interactions with customers is The Best Service Is No Service: How to Liberate Your Customers From Customer Service, Keep Them Happy, and Control Costs.10 Author Bill Price is the former vice president of Global Customer Service at Amazon.com, certainly a sterling example of a highly competent customer-strategy enterprise, and coauthor David Jaffe is a consultant in Australia focused on helping companies manage their customer experiences. In this excerpt from The Best Service Is No Service, the authors consider all the ways customers can be simply annoyed at the necessity of contacting the companies they buy from and interacting with them.

When the Best Contact Is No Contact

Let’s consider how often some organizations force us to make contact with them:

- A leading cable TV company requires three contacts for each new connection—why not just one contact?

- Some mobile phone companies handle as many as ten to twelve contacts per subscriber per year, whereas others have only three to four. Why do we need to call mobile providers so often? Shouldn’t we just be making calls and paying bills, preferably online?

- A water utility was averaging two contacts for each fault call. The first call should have been enough to fix the problem. The subsequent calls asked, “Why isn’t it fixed yet?” or “When are you coming to fix it?”—not good enough.

- A leading self-service bank averaged one contact per customer per year and nearly two for each new customer. Don’t we sign up for self-service applications like Internet banking so that we don’t have to call? Other banks have half this contact rate, so clearly something is broken.

- A leading insurance company was averaging more than two contacts per claim. The first contact makes sense, setting the claim in motion, but why were the subsequent contacts needed?

- “Customers reported making an average of 3.5 contacts in an attempt to resolve their most serious customer-service problem in the past year.”a Why isn’t this 1.0 contact or, perish the thought, zero contacts because nothing needs to be resolved in the first place?

We should make it clear that we are not talking about such interactions as placing orders, making payments, or using self-service solutions, such as checking balances, that the customers chose to use. Instead, we are talking about having to call or take the time to write or visit a branch to get something done or to get something fixed. In some industries, these contact rates are much worse: Every contact with a technical support area of an Internet provider or computer manufacturer is a sign that something is broken. Ideally, customers should never need to make these contacts.

aSpencer, “Cases of ‘Customer Rage’ Mount as Bad Service Prompts Venting,” Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2003, p. D4.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Bill Price and David Jaffe, The Best Service Is No Service: How to Liberate Your Customers from Customer Service, Keep Them Happy, and Control Costs (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008), p. 7.

Tapping into feedback from customers is an immensely powerful tactic for improving a company’s sales and marketing success. But customers will share information only with companies they trust not to abuse it. (See Chapter 9 for more on privacy issues.) Here are some ways to earn this trust, encouraging customers to participate more productively, improving both the cost efficiency and the effectiveness of customer interactions:

- Use a flexible opt-in policy. Many opt-in policies are all-or-nothing propositions, in which customers must elect either to receive a flood of communications from the firm, or none at all. A flexible opt-in policy will allow customers to indicate their preferences with regard to communication formats, channels, and even timing. To the extent possible, give customers a choice of how much communication to receive from you, or when, or under what conditions.

- Make an explicit bargain. Customers have been used to getting news and entertainment for free, in exchange for being exposed to ads or other commercial messages. As customers gain more power to zap commercials, eliminate pop-ups, and avoid unwanted calls, SMS messages, and e-mail they consider to be spam, marketers who want to talk to customers may need to make an explicit offer, something like this: Watch the last episode of your favorite weekly show on ABC.com and, when you do, we’ll post commercial messages from sponsors for your viewing three times during the show, and you’ll need to click your way through it to show us you see it. Or pay $4.00 to download the show and watch it without commercials.

- Tread cautiously with targeted Web ads. Even though targeted online ads are popular with marketers, research has shown that consumers are especially wary of sharing information when targeted Web ads are the result. This doesn’t mean don’t do it, but it does mean don’t pile on. In any case, for behavioral targeting to succeed, an enterprise must have the customer’s informed consent.

- Make it clear and simple. Have a clear, readable privacy policy for your customers to review. Procter & Gamble (P&G) provides a splendid example. Instead of posting a lengthy document written in legalese, P&G presents a one-page, easy-to-understand set of highlights outlining the policy, with links to more detailed information. By contrast, Sears Holding Company, in its online offer to consumers to join the “My Sears Holding Community,” has a scroll box outlining the privacy policy that holds just 10 lines of text but requires you to read 54 boxfuls to get through the whole policy. Buried far into the policy is a provision that lets the firm install software on your computer that “monitors all of the Internet behavior that occurs on the computer.”11

- Create a culture based on customer trust. Emphasize the importance of privacy protection to everyone who handles personally identifiable customer information, from the chief executive officer to contact center workers. Line employees provide the customer experiences that matter, and employees determine whether your privacy policy becomes business practice or just a piece of paper. If your business culture is built around acting in the interest of customers at all times, then it will be second nature at your company to protect customers from irritating or superfluous uses of their personal information—things most consumers will regard as privacy breaches, whether they formally “agreed” to the data use or not.

- Remember: You’re responsible for your partners too. It should go without saying that whatever privacy protection you promise your customers, it has to be something your own sales and channel partners—as well as your suppliers and other vendors—have also agreed to, contractually. Anyone in your “ecosystem” who might handle your own customers’ personally identifiable information and feedback will have the capacity to ruin your own reputation. Take care not to let that happen!

If an enterprise wants to conduct dialogues with customers, it must remember that the customers themselves must want to engage in these dialogues. Simply contacting a customer, or having the customer contact the enterprise, does not constitute dialogue, and will likely convey no marketing benefit to the enterprise.

Is the Contact Center a Cost Center, a Profit Center, or an Equity-Building Center?

Judi Hand

President and General Manager, Direct Alliance

We have all become very familiar with “call centers.” With all the technology that permeates our homes and our lives, undoubtedly we have all had to call an 800 number. This experience typically has been associated with long, confusing interactive voice response (IVR) menus, a single way of communicating, agents with poor English skills, and a frustrating lack of resolution. In a quest to lower support costs, companies have sacrificed the customer experience. A vicious cycle has emerged, driven by the focus on single metrics such as cost per call. Although companies may think they are lowering the cost to serve by focusing on this metric, the reality is that overall costs increase in the face of repeat calls, rework, and—most damaging to shareholder value—customer churn.

Enlightened companies are realizing they can turn this vicious cycle into a virtuous one. A virtuous cycle looks at the entire customer experience and focuses on metrics such as cost to serve and cost to retain. It starts with mapping out integrated touch plans for every customer segment, all the way down to segments of one. An integrated touch plan is the conversation that you want to have with a customer over their life cycle. It defines the key messages that you want to send with each and every interaction. It cuts across multiple channels of communication from voice, to chat, to SMS and online communities.

This is changing the very nature of call centers and transforming them into customer interaction centers. A customer interaction center handles all calls, regardless of type, for a certain customer segment or customer portfolio. Although there still may be an IVR, it is simplified with only a few choices. The interaction center associate is cross-trained to handle many different questions, issues, and tasks. This cross-training includes the ability to turn service calls into sales opportunities.

An integrated customer experience such as this typically involves multiple legacy systems. But desktop tools are available that help simplify the job of bringing together information about a customer. For example, a “single sign-on,” which allows the associate to sign in once and have access to all applications necessary to do the job, can lower average handle times (AHT) by up to 10 percent. Another tool would be a “desktop wrapper,” which picks up information that is required multiple times, such as a serial number or a telephone number. This “wrapper” will prepopulate all the applications that require it so that the associate does not have to spend time reentering the same information over and over again. It also results in lower AHTs. The result is an overall lower cost to serve, lower cost to acquire, and lower cost to retain. A major global consumer electronics company has implemented this customer experience strategy. It combined sales, care, and technical support functions into one integrated organization. It offers both voice and chat support. The center is “virtual” to take advantage of the “right shore” for the work. Within six months of launch, this center has driven down the cost to serve, increased revenue per call, and increased customer satisfaction.

Technology is also playing a major role in the transformation of customer support. Today’s young adults have grown up in a wireless, borderless world. Most would rather instant message their “chat” with a service associate than talk. It is imperative that any customer experience strategy offer this option. Best-in-class providers have associates handling up to four chats at once, thus driving strong cost savings.

Another emerging trend is the use of blogs and forums for customer support. According to Gartner, “By 2012, 65 percent of support conversations will happen outside of your enterprise.”a It is imperative that companies integrate traditional CRM channels with these new social CRM communities. One way to do this is to create a certified knowledge base. This base will capture all the information being shared across these interactions so that all associates have the benefit of the most up-to-date knowledge about a given topic. For example, I posed a question on a blog about accidentally running my son’s iPodTouch through the washing machine. I wanted to know if there was anything that I could do to save it. The blog community suggested that I immediately submerge the device in uncooked rice and leave it there for 48 hours. The rice would absorb the liquid and—with any luck—save the device. This is not the kind of information that you can predict needing, so you can’t really train support associates to deliver it, but it is important that they are aware of the advice being offered through crowd service if customers who call in ask about it. A certified knowledge base can assure this.

In summary, the industry is moving away from point solutions that address only a small part of the total customer experience, to integrated multichannel solutions. These solutions offer customers the choice of how they want to communicate, on their terms, and help a firm remember all the previous “conversations” with a customer.b The measures of success move from productivity measures to bottom line business outcomes.

aK. Collins, “CRM ‘hype’ continues, but maturity and adoption of enabling technologies vary widely,” September 8, 2008, accessed March 9, 2009, available at: http://blog.gartner.com/blog/crm.php.

bBased on what Don Peppers and Martha Rogers call a “Learning Relationship.”

Cost Efficiency and Effectiveness of Customer Interaction

Regardless of how automated they are, every interaction with a customer does cost something, if only in terms of the customer’s own time and attention, and some interactions cost more than others. The cost of customer interaction can be minimized partly by reducing or eliminating the interactions that the customer does not want. But ranking customers by their value also allows a company to manage the customer interaction process more cost efficiently. A highly valuable customer is more apt to be worth a personal phone call from a manager while a not-so-valuable customer’s interaction might be handled more efficiently on the Web site. An enterprise requires a manageable and cost-efficient way to solicit, receive, and process the interactions with its customers. It will need to categorize customer inquiries and responses in some effective way so it can customize its interactions for each customer.

Customer-strategy enterprises concentrate not just on the efficiency of the communication channel used for interactions with the customer but also on the effectiveness of the customer dialogue itself. Measuring efficiency might include tracking the percent of inbound customer inquiries satisfactorily answered by the enterprise’s Web site FAQ section, or monitoring how long customers stay on hold with the customer service department before they disconnect. Measuring effectiveness might include tracking first-call resolution, or the ratio of complaints handled or problems resolved on the first call. Critical to the success of any dialogue, however, is that each successive interaction with the individual customer be seen as part of a seamless, flowing stream of discussion. Whether the conversation yesterday took place via mail, phone, the Web, or any other communication channel, the next conversation with the customer must pick up where the last one left off.

For decades now, technology has been dramatically reducing the expenses required for a business to interact with a wide range of customers. Enterprises can now streamline and automate what was once a highly manual process of customer interaction. Different interactive mechanisms can yield widely different information-exchange capabilities, such as speed trackability, tangibility (the ability to hold it or refer back to it later), and personalization. Interacting regularly with a customer via a Web site is usually highly cost-efficient, and can be customer-driven, yielding a rich amount of information. Postal mail is not as practical for dialogue, because it involves a lengthy cycle time, although it can prove effective for delivering more detailed information to the customer, who can keep the hard copy to read later—hard copy that might include glossy photos or diagrams harder to render online. Telephone interaction has the advantages of real-time conversation, but neither phone nor face-to-face interaction facilitates easy tracking of the content of these conversations, and the enterprise trying to employ voice interactions to strengthen its customer relationships must be sure the employees responsible for the interactions are diligently and accurately capturing the key elements of customer dialogues (although scripted phone calls can aid in this effort).

Complaining Customers: Hidden Assets?

Customers generally contact an enterprise of their own volition for only three reasons: to get information, to obtain a product or service, or to make a suggestion or a complaint. Despite the fact that technology should make it easier for customers to contact companies, the Technical Assistance Research Program (TARP) found that customer complaints are declining; not because there are fewer problems but likely because, unfortunately, customers have been trained to expect problems as part of the cost of doing business.12 But sometimes a complaint can provide an opportunity for real dialogue.

Thus, one way to view a complainer is to see him as a customer with a current “negative” value that can be turned into positive value. In other words, a complainer has extremely high potential value. If the complaint is not resolved, there is a high likelihood that the complaining customer will cease buying, and will probably talk to a number of other people about his dissatisfaction, causing the loss of additional business. The customer-oriented enterprise, focused on increasing the value of its customer base, will see a customer complaint as an opportunity to convert the customer’s immense potential value into actual value, for three reasons:

1. Complaints are a “relationship adjustment opportunity.” The customer who calls with a complaint enables the enterprise to understand why their relationship is troubled. The enterprise then can determine ways to fix the relationship.

2. Complaints enable the enterprise to expand its scope of knowledge about the customer. By hearing a customer’s complaint, the enterprise can learn more about the customer’s needs and strive to increase the value of the customer.

3. Complaints provide data points about the enterprise’s products and services. By listening to a customer’s complaint, the enterprise can better understand how to modify and correct its generalized offerings, based on the feedback.

To a customer-centered enterprise, complaining customers have a collaborative upside, represented by a high potential value.