Chapter 5

Differentiating Customers: Some Customers Are Worth More than Others

The result of long-term relationships is better and better quality, and lower and lower costs.

—W. Edwards Deming

All value created by a business comes from customers. Without a customer or client, at some level, no business can create any shareholder value at all, and this simple fact is inherent in the very nature of a business. By definition, a business exists to create and serve customers and, in so doing, to generate economic value for its stakeholders. But some customers will create more value for a business than others will, and understanding the differences among customers, in terms of the value they each will or could create, is critical to managing individual customer relationships. In this chapter, we explore the most fundamental ideas about the value that customers represent for an enterprise, including both a customer’s “actual” value and “potential” value. We show how a firm can use insights about customer value to better allocate resources and prioritize sales, marketing, and service efforts. We consider whether and under what conditions a firm should consider “firing” very low-value or even negative-value customers.

Identifying each customer individually and linking the information about that customer to various business functions prepares the customer-strategy enterprise to engage each customer in a mutual collaboration that will grow stronger over time. The first step is to identify and recognize each customer at every touchpoint. As we saw in Chapter 4, when the “identify” task is properly executed, information about individual customers should allow a company to see each customer completely, as one customer throughout the organization. And seeing customers individually will enable the company to compare them—to differentiate customers, one from another. By understanding that one customer is different from another, the enterprise reaches an important step in the development of an interactive, customer-centric Learning Relationship with each customer.

The inability to see customers as being different does not mean the customers are the same in needs or value, only that the firm sees them that way.

The inability to see customers as being different does not mean the customers are the same in needs or value, only that the firm sees them that way. Understanding, analyzing, and profiting from individual customer differences are tasks that go to the very heart of what it means to be a customer-strategy or customer-centric enterprise—an enterprise that engages in customer-specific behaviors, in order to increase the overall value of its customer base.

Customers are different in two principal ways: Different customers have different values to the enterprise, and different customers have different needs from the enterprise. The entire value proposition between an enterprise and a customer can be captured in terms of the value the customer provides for the firm and the value the firm provides for the customer (i.e., what needs the firm can meet for the customer). All other customer differences, from demographics and psychographics, to behaviors, transactional histories, and attitudes, represent the tools and concepts marketers must use simply to get at these two most fundamental differences.

Knowing which customers are most valuable and least valuable to the enterprise will enable a company to prioritize its competitive efforts, allocating relatively more time, effort, and resources to those customers likely to yield higher returns. In effect, an enterprise’s financial objectives with respect to any single customer will be defined by the value the customer is currently creating for the enterprise (her actual value) as well as the potential value the customer could create for the enterprise, if the firm could present the exact right offerings at the right time as needed by the customer and thus change the customer’s behavior in a way that works for both the customer and the enterprise. Of course, changing a customer’s behavior (which is the basic objective of all marketing activity) can be accomplished only by appealing to the customer’s own personal motives, or needs. So while understanding a customer’s value profile will determine a firm’s financial objectives for that customer, the strategies and tactics required to achieve those objectives require an understanding of that customer’s needs. It should be noted that a customer has value to the enterprise in two ways that matter to shareholders and decision makers: A customer has current value (revenue minus cost to serve) as well as long-term value in the present that goes up or down based on experience with the company or brand, influence from the outside, and changes in his own needs.

In this chapter, we discuss the concept of customer valuation, including various ways a company might rank its customers by their individual values to the enterprise. In Chapter 6, we address the issue of customer needs. Importantly, we return again and again throughout the book to these two issues: the different valuations and needs of different individual customers. For instance, we return to the issue of short-term and long-term customer valuation in Chapter 11, when we discuss metrics and measurements. And we come back to the issue of customer needs during our discussion of customization and mass customization in Chapter 10.

Customer Value Is a Future-Oriented Variable

Mail-order firms, credit card companies, telecommunications firms, and other marketers with direct connections to their consumer customers often try to understand their marketing universe by doing a simple form of prioritization called decile analysis—ranking their customers in order of their value to the company and then dividing this top-to-bottom list of customers into 10 equal portions, or deciles, with each decile comprising 10 percent of the customers. In this way, the marketer can begin to analyze the differences between those customers who populate the most valuable one or two deciles and those who populate the less valuable deciles. A credit card company may find, for instance, that 65 percent of top-decile customers are married and have two cards on the same account while only 30 percent of other, less valuable customers have these characteristics. Or a catalog company may find that a majority of customers in the bottom three or four deciles have never before bought anything by direct mail while 85 percent of those in the top two deciles have.

It would not be unusual for a decile analysis to reveal that 50 percent, or even 95 percent, of a company’s profit comes from the top one or two deciles of customers. Mail-order houses and other direct marketers are more likely than other marketers to have used decile analysis in the past, largely as a means for evaluating the productivity of their mailing campaigns, but this kind of customer ranking analysis will become increasingly important as more companies begin to adopt a customer focus.1

But just how does a company rank-order its customers by their value in the first place? What data would the credit card company use to analyze its customers individually and then array them from top to bottom in terms of their value? And what variables would go into the mail-order firm’s customer rankings? What do we mean when we talk about the value of a customer, anyway?

For our purposes, the value a customer represents to an enterprise should be thought of as the same type of value any other financial asset would represent. To say that some customers have more value for the enterprise than others is merely to acknowledge that some customers are more valuable, as assets, than others are. The primary objective of a customer-strategy enterprise should be to increase the value of its customer base, for the simple reason that customers are the source of all short-term revenue and all long-term value creation, by definition. In other words, a company should strive to increase the sum total of all the individual financial assets known as customers.

But this is not as simple as it might sound, because in the same way any other financial asset should be valued, a customer’s value to the enterprise is a function of the profit the customer will generate in the future for the enterprise.

Let’s take a specific example. Suppose a company has two business customers. Customer A generated $1,000 per month in profit for the enterprise over the last two years while Customer B generated $500 in monthly profit during the same period. Which customer is worth more to the enterprise?

Knowing only what we’ve been told so far, we can say it’s probable that Customer A is worth more than Customer B, but this is not a certainty. If Customer A were to generate $1,000 in profit per month in all future months while Customer B were to generate $500 per month in all future months, then certainly A is worth twice as much to the enterprise as B. But what if we know that Customer A plans to merge its operations into another firm in three months and switch to a different supplier altogether while Customer B plans to continue doing its regular volume with the company for the foreseeable future? In that case, our ranking of these two customers would be reversed, and we would consider B to be worth more than A. However, if what actually happened was that a competitor derailed A’s merger while B went bankrupt and ceased all operations the following month, then our assessment would still be wrong.

By definition, a customer’s value to an enterprise, as a financial asset, is a future-oriented variable. Therefore, it is a quantity that can truly be ascertained only from the customer’s actual behavior in the future. We mortals can analyze data points from past behavior, we can interview a customer to try to understand the customer’s future opportunities and intent, and we can even conclude contractual agreements with customers to guarantee performance for the contract period, but the plain truth is that, without clairvoyant powers, we can’t know what a customer’s true value is until the future actually happens.

However, until that future does happen, we can affect its outcome—at least partially—by our own actions. Suppose we were to find a revenue stream for Customer B that allowed it to continue in business rather than going bankrupt. By our own deliberate action, in this case, we would have changed B’s value to our firm as a financial asset.

To think about customer valuation, therefore, we need to use two different but related concepts:

1. Actual value is the customer’s value, given what we currently know or predict about the customer’s future behavior.

2. Potential value is what the customer’s value as an asset to the enterprise could represent if, through some conscious strategy on our part, we could change the customer’s future behavior in some way.

Customer Lifetime Value

The “actual value” of a customer, as we defined it, is equivalent to a quantity frequently termed customer lifetime value (LTV). Defined precisely, a customer’s LTV is the net present value of the expected future stream of financial contributions from the customer.2 Every customer of an enterprise today will be responsible for some specific series of events in the future, each of which will have a financial impact on the enterprise—the purchase of a product, payment for a service, remittance of a subscription fee, a product exchange or upgrade, a warranty claim, a help-line telephone call, the referral of another customer, and so forth. Each such event will take place at a particular time in the future and will have a financial impact that has a particular value at that time. The net present value (NPV), today, of each of these future value-creating events can be derived by applying a discount rate to it to factor in the time value of money as well as the likelihood of the event. LTV is, in essence, the sum of the NPVs of all such future events attributed to a particular customer’s actions.

One useful way to think about the different types of events and activities that different customers will be involved in is to visualize each customer as having a “trajectory” that carries the customer through time in a financial relationship with the enterprise. For example, a customer could begin his relationship at a particular starting point and at a particular spending level. At some point, he increases his spending, taking another product line from the company; later he also begins paying more for some added service. Still later he has a complaint, and it costs the company some expense to resolve it. He refers another customer to the company, and that customer then begins her own trajectory, creating a whole additional value stream. Eventually, perhaps several years or decades later, the original customer “leaves the franchise,” because his children grow up, or he decides to switch to another product altogether, or he gets divorced, or retires, or dies. At this point, his relationship with the enterprise comes to an end. (We could describe a business customer’s trajectory in the same way. Although a “business” may have an indefinite future potential as a customer, each of the individual potential end users, purchasing agents, influencers, and so forth eventually will quit, get promoted or transferred, or fired, retire, or die.)

Different customers will have different trajectories. In a way, the lifetime value of each customer amounts to the NPV of the financial contribution represented by that customer’s trajectory through the customer base. From a customer’s stream of positive contributions, including product and service purchases, an enterprise must deduct the expenses associated with that customer, including the cost of maintaining a relationship. For instance, relationships usually require some amount of individual communication, via phone, mail, e-mail, or face-to-face meetings. These costs, along with any others that apply to a specific individual customer, will reduce the customer’s LTV. It sometimes happens that the costs associated with a customer actually outweigh the customer’s positive contributions altogether, in which case the customer’s LTV is below zero.

We are using the term contribution, as opposed to profit, deliberately, because the value of a particular customer is equivalent to the marginal contribution of that customer, when he is added to the business in which the enterprise is already engaged. Suppose we add up all the positive and negative cash flows an enterprise will generate over the next few years, and the total is $X. But then Customer A’s trajectory of financial transactions is removed from the enterprise, and the positive and negative cash flows will only amount to a lesser total of $Y. The customer’s marginal contribution is equal to X – Y. The NPV of those various contributions by Customer A is the customer’s LTV. There are additional “contributions” a customer can make, not all of them monetary. Aside from the obvious word-of-mouth given by a customer, a nonprofit organization looks to volunteer work or other participation.

In practice, of course, it is not possible for an enterprise to know what any particular customer’s future contributions will actually be, and if we want to be able to make current decisions based on this future-oriented number, then we will have to estimate it in some way. Traditionally, the most reliable predictor of a customer’s future behavior has been thought to be that customer’s past behavior. We are usually quite justified in making the commonsense assumption that a customer who has generated $1,000 of profit each month for the last two years will continue to generate that profit level for some period of time in the future, even though we simultaneously acknowledge that any number of forces can appear that will change this simplistic trend at any moment. Various computational techniques can be used to model the probable trajectories of particular types of customers more precisely and to project these expected trajectories into the future. Some companies have customer databases that allow highly sophisticated modeling and analysis. Such analysis can sometimes be used to give an enterprise advance warning when a credit card customer, or a cell phone customer, or a Web site subscriber, is about to defect to a competitor. A whole class of statistical analysis tools, frequently termed predictive analytic, is designed to help businesses sift through the historic records of certain types of customers, in order to model the likely behaviors of other, similar customers in the future.

According to the late CRM consultant Frederick Newell, LTV models have a number of uses. They can help an enterprise determine how much it can afford to spend to acquire a new customer or perhaps a certain type of new customer. They can help a firm decide just how much it would be worth to retain an existing customer. With a model that predicts higher values for certain types of customers, an enterprise can target its customer acquisition efforts in order to concentrate on attracting higher-value customers. And, of course, the LTV measurement represents a more economically correct way to evaluate marketing investments compared to simply counting immediate sales.3

Although sophisticated modeling methods help to quantify LTV, many variables cannot be easily quantified, such as the assistance a customer might give an enterprise in designing a new product, or the value derived from the customer’s referral of another customer, or the customer’s willingness to advocate for the product or company on a social networking Web site. Any model that attempts to calculate individual customer LTVs should employ some or all of these data, quantified and weighted appropriately:

- Repeat customer purchases

- Greater profit and/or lower cost (per sale) from repeat customers than from initial customers (converting prospects)

- Indirect benefits from customers, such as referrals (Imagine that you are a book author and Oprah Winfrey bought and likes your book!)

- Willingness to collaborate—the customer’s level of comfort and trust with the company and participation in data exchange that results in the opportunity for better customer experience (sometimes called relationship strength)

- Customers’ stated willingness to do business in the future rather than switch suppliers

- Customer records

- Transaction records (summary and detail)

- Products and product costs

- Cost to serve/support

- Marketing and transaction costs (including acquisition costs)

- Response rates to marketing/advertising efforts4

- Company- or industry-specific information

The objective of LTV modeling is to use these and other data points to create a historically quantifiable representation of the customer and to compare that customer’s history with other customers. Based on this analysis, the enterprise forecasts the customer’s future trajectory with the enterprise, including how much he or she will spend, and over what period.

For our purposes, it is sufficient to know that:

- The actual value of a customer is the value of the customer as a financial asset, which is equivalent to the customer’s lifetime value—the NPV of future cash flows associated with that customer. (This is the current value, assuming business as usual.)

- LTV is a quantity that no enterprise can ever calculate precisely, no matter how sophisticated its predictive analytics programs and statistical models are.

- Nevertheless, even though it can never be precisely known,5 LTV is a real financial number, and every enterprise has an interest in understanding and positively affecting its customers’ LTVs to the extent possible, and—as we shall see in Chapter 13—to hold members of the organization responsible for exactly that.

As difficult as LTV and actual value may be to model, potential value is an even more elusive quantity, involving not just guesses regarding a customer’s most likely future behavior but guesses regarding the customer’s options for future behavior.

Still, potential value isn’t impossible to estimate, especially if the analysis begins with a set of customers who have already been assigned actual values or LTVs. Probably the most straightforward way to estimate a customer’s potential value is to look at the range of LTVs for similar customers and then to make the arbitrary assumption that in an ideal world it should at least be possible to turn lower-LTV customers into higher-LTV customers. In the consumer business, this means examining the LTVs for customers who are perhaps at the same income level, or have the same family size, or live in the same neighborhoods. For business-to-business (B2B) customers, it would mean comparing the LTVs of corporate customers in the same vertical industries, with the same sales levels, or profit, or employment levels, and so forth and better decisions.

The problem at many companies is that a customer’s “value to the firm” is confused with the customer’s current profitability. Often, measuring customer profitability at all, even in the short term, is an achievement for a firm. But when a customer’s LTV is taken into account, the results will be more revealing, and estimating potential values will yield still more insight.

Recognizing the Hidden Potential Value in Customers

Pelin Turunc

Consultant, Peppers & Rogers Group, Europe

Differentiating or grouping customers in terms of various characteristics such as value, needs, and behavioral trends has proven to be an effective and widely accepted marketing practice among a variety of industries across the world. The most widely used segmentation method, pursued by the vast majority of companies focused on a customer strategy, involves differentiating customers by value and then designing different strategies for different value segments—launching aggressive retention strategies for high-value customers, for instance. Even though it is a popular strategy, many companies still succumb to a costly pitfall, related to just how a customer’s value is assessed. Far too frequently, companies take into account only the narrow viewpoint of the customer’s current “actual value,” largely based on historical behavior patterns, (this phrase actually only applies to “actual value”) while overlooking the immense potential of many customers to generate even more value than they have in the past or to generate value not directly indicated by transactional records or the historical picture.

It is understandable, of course, that a firm’s marketing analysts may be reluctant to forecast future behaviors for a customer when they haven’t already observed and modeled those behaviors in the customer’s transactional history. In addition, analysts may hesitate to try to quantify the results of customer behaviors that are not directly associated with purchasing and service costs. However, leading companies know that success often comes from taking account of individual customers’ potential values, not just their actual values. (Remember that both current value and actual value are “future” oriented, but, while a customer’s current value is the estimated net present value of future financial contributions currently expected, based on what is known now, a customer’s potential represents the increased value that could be realized if the customer were to behave differently, presumably based on the firm’s behavior.)

Consider, for instance, the idea that today’s customer might actually increase his or her patronage with a firm considerably, based solely on the fact that, as time goes on, the customer matures into an older and more productive person. Royal Bank of Canada (RBC)a was one of the first banks to look carefully and analytically at the youth segment as a promising group of retail banking customers when most banks were overlooking this segment due to their low current (actual) value. RBC recognized the high potential value of young college students, many of whom would become highly paid professionals in the future. The bank gained a competitive advantage by reaching out to and building loyalty in this segment early on. In a similar way, certain groups of customers who are in a temporary financial slump, or even in bankruptcy, could have the potential to be promising and high-value customers in the future. A bank that identifies such customers (differentiating them from other customers who are bankrupt now and likely to remain in financial distress for the long term) and reaches out to them at this difficult stage in their lives is certain to win these customers’ loyalty and trust.

In telecommunications, some companies find hidden word-of-mouth power in the ranks of their currently low-value “public sector employees” segment. For example, when Sprint offered attractive rates and group discounts to this public sector group, the word-of-mouth impact resulted in increased new customer acquisitions, increasing each company’s profitability and market share.b A close look at the needs of the customers was of course an enabling step in this strategy, where the telecommunications company was able to find the rate, payment, or discount benefits that best suited the needs and payment behavior of this customer group. The benefits could easily have been missed, however, had this company looked solely at these customers’ historically based actual values.

Taking into account the “customer influence” factor in modeling lifetime value is even more critical in some industries where a small number of customers exert a disproportionate share of influence on others’ buying decisions, such as in the pharmaceuticals industry. The primary customers here, at least in most countries, are physicians, and some physicians almost always stand out for the amount of influence they have on the medical practices of other physicians. Identifying and trying to quantify the value of such “key opinion leaders” (KOLs) is a high priority for pharmaceutical companies, such as Abbott Labs, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Biogen Idec.c KOLs usually are viewed by their peers as experts in specific therapeutic areas, and as such they exert immense influence over other doctors when it comes to the types of medications to be prescribed and the kinds of medical treatments to be administered in these therapeutic areas. Even though some KOLs may have low actual values themselves, in terms of the prescriptions they write in their own medical practice, their influence is disproportionately valuable. Some pharmaceutical companies (e.g., Roched) even try to identify rising KOL stars, who are for the most part relatively less well-known professionals who show signs of future success and influence. The companies then invite these rising stars to participate in medical education and other activities, hoping to build long-lasting relationships.

One industry in which potential value can be an important differentiator is the airline business. Because of their widely used frequent-flyer programs, airlines usually have a fairly good handle on the transactional histories of their most frequent travelers who are, for the most part, business flyers. But even if a business traveler flies 50,000 miles a year on an airline, the airline has no way of knowing, from its own transactional records, whether that traveler is flying another 50,000 miles on a competitive carrier. So, in trying to estimate the potential value of an airline customer, it is critical to look at external data sources (and, in some cases, simply to ask a customer in order to get share-of-customer information) when such sources are available and perhaps to tap into the data available from distributor partners, such as travel agencies or credit card firms. Lifestyle changes can also create shifts in the potential value of a customer and should be taken into account. Southwest Airlines, for example, identified and sent relevant offers to some currently low-value customers who moved to another country as expatriates, and these customers proved to have high potential value as evidenced by their future travels on holidays to their home country.

In addition to overlooking customers with high potential value, some companies make wrong and unprofitable investments in customers who seem to be high in value now but in fact have a low or sometimes negative potential value. In the retailer category, Best Buye successfully differentiated its customers to deliver exceptional treatment to identified high-potential customers while paring some of their less valuable customers from their mailing lists and tightening up their return policies to prevent abuse. In this way, Best Buy avoided unnecessary time and monetary investment on customers with low potential values. Filene’s Basement Discount Storesf represents a more extreme example. When Filene’s Basement realized that some of its customers who appeared to be high-value customers with high sales volumes were actually serial returners (often returning clothing after using it once), it banned some of them from its stores altogether, preventing losses from this group who proved to be Below Zero over the long term.

Another company that avoided unnecessary investment in low-potential-value customers is Capital One Bank, which recognized its low potential value customers and adjusted its reactive retention strategy to deemphasize them. (After all, why should the company go out of its way to retain a low-value customer?) One variable that can reduce the potential value of a financial services customer is financial risk. Understanding the likelihood that a customer will need to be charged off in the future is an important function for any credit-granting institution. Capital One, while giving incentives and positive offers to its high-value customers who want to close their accounts in order to save them, encouraged the high-risk customers (i.e., low-potential-value customers) to close their accounts with the bank. This policy helps to minimize future financial losses to the bank, improving overall profitability.

Assessing customer value as a combination of current and potential value is no longer a choice if a firm wants to remain truly competitive. Estimating a customer’s potential value is certainly more complex than simply trying to forecast actual value, or LTV, and requires a deeper look into factors such as needs, lifestyle phases, and behavioral trends. But making a genuine attempt to do so will likely prove quite beneficial.

aV.G. Narayanan and Lisa Brem, “Case Study: Customer Profitability and Customer Relationship Management at RBC Financial Group (abridged),” Journal of Interactive Marketing 16, no. 3 (Summer 2002): 76.

bAdvisory Opinion No. 05-1, “Conditions under which a State Employee May Accept a Discount on Goods or Services”; Sprint PCS (“Sprint”) provides wireless telephone services for OTDA and other state agencies through a contract approved by the State Office of General Services (2004), available at: www.nyintegrity.org/advisory/ethc/05-01.htm, accessed September 1, 2010. Sprint PCS company Web site and Nextel company Web site indicate 15 percent for government employees, available at: www.nextel.com/en/solutions/federal_govt.shtml.

cRachel Farrow, “Forging Key Opinion Leader Relationships: Developing the Next Generation,” TVF Communications ( July 2008); available at: www.tvfcommunications.com/publications.aspx, accessed September 1, 2010.

dIbid.

eRajiv Lal, Carin-Isabel Knoop, and Irina Tarsis, “Best Buy Co., Inc.: Customer-Centricity,” Harvard Business School Cases, April 1, 2006, p. 1.

fScott Wilkerson, “Marketers Must Understand Customer Value to Make Segmentation Pay,” Hawkpartners Group, Alert! Magazine, September 10, 2009, available at: www. hawkpartners.com/perspectives/articles/alert-mag-October-2009.pdf, accessed September 1, 2010.

Growing Share of Customer

With respect to its relationship with a customer, the goal of any customer-strategy enterprise should be to positively alter the customer’s financial trajectory, increasing the customer’s overall value to the enterprise. The challenge, however, is to know how much the enterprise really can alter that trajectory— how much increase in the customer’s value an enterprise can actually generate.

Unrealized potential value is a term used to denote the amount by which the enterprise could increase the value of a particular customer if it applied a strategy for doing so. It’s a very straightforward concept, really, because the unrealized potential of a customer is simply the difference between the customer’s potential value and actual value. It represents the potential additional business a customer is capable of doing with the enterprise, much of which may never materialize. As an enterprise realizes more and more of a customer’s potential value, however, it can be said to have a greater and greater share of that customer’s business. (Indeed, if we divide a customer’s actual value by the customer’s potential value, the quotient should give us “share of customer.”)

Increasing share of customer6 is an important goal for a customer-strategy enterprise and can be accomplished by increasing the amount of business a customer does, over and above what was otherwise expected (i.e., by applying a strategy to favorably affect the customer’s trajectory). This is often referred to as “share of wallet.” For example, a bank might have a relationship with a customer who has a checking account, an auto loan, and a certificate of deposit. The customer provides a regular profit to the bank each month, generated by transaction fees and the investment spread between the bank’s own investment and borrowing rates, compared to the lending and savings rates it offers the customer. The net present value of this income stream over the customer’s likely future tenure is the customer’s LTV. This LTV amount is equivalent to the present value of the financial benefits the bank would lose in the future, if the customer were to defect to another financial services organization today.

But suppose that, in addition to the accounts the customer now maintains at the bank, he also has a home mortgage at a competitive institution. This loan represents unrealized potential value for the bank, while it represents actual value to the bank’s competitor. The expected profit from that loan is one aspect of the customer’s potential value to the bank, which may devise a strategy to win the customer’s mortgage loan business away from its competitor.

Or suppose this customer owns a home computer and modem but doesn’t participate in the bank’s online banking service. If he were to do more of his banking online, however, the cost of handling his transactions would decline, his likelihood of defection would decline, and his value to the bank would increase. Thus, the increased profit the bank could realize if the customer banked online represents another aspect of the customer’s potential value to the bank.

Or perhaps the customer is a night student attempting to qualify for a more financially rewarding career. If the bank could help him achieve this objective, he would earn more money and do more banking, and his value to the bank would increase. All these possibilities represent real opportunities for a bank to capture some of a customer’s unrealized potential value.

Assessing a Customer’s Potential Value

In trying to assess a particular customer’s potential value, some of the questions you want to answer include:

- How much of the customer’s business currently goes to your competition, but might be pried away with the right approach or relationship?

- How much more of a customer’s business could you capture if you modify your treatment of him?

- How many more product lines might the customer buy from you? What other services or products could you sell the customer if you had the products available?

- What additional value would you capture if you could prevent the customer’s defection?

- The customer has needs you know about. How can you identify the needs you don’t yet know about?

- How much could you reduce the cost of serving this customer, while maintaining his satisfaction?

- How much could this customer be worth in terms of referrals and other non-monetary contributions?

Your opportunity for organic growth is directly related to the unrealized potential values of your current and future customers. But that is just your perspective. From the customer’s perspective, potential value has to do with [the customer’s] need. This is important:

The outside limit of any customer’s value is defined by the customer’s need, not by your current product or service offering.

Source: Excerpted from Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, Ph.D., Return on Customer (New York: Currency/Doubleday, 2005), p. 82.

Different Customers Have Different Values

Increasing a customer’s value encompasses the central mission of an enterprise: to get, keep, and grow its customers. When it understands the value of individual customers relative to other customers, an enterprise can allocate its resources more effectively, because it is quite likely that a small proportion of its most valuable customers (MVCs) will account for a large proportion of the enterprise’s profitability. This is an important principle of customer differentiation, and at its core is what is known as the Pareto principle, which asserts that 80 percent of any enterprise’s business comes from just 20 percent of its customers.7 The Pareto principle implies that a mail-order company ordering its customers into deciles by value is likely to find that the top two deciles of customers account for 80 percent of the business the company is doing. Obviously, the percentages can vary widely among different businesses, and one company might find that the top 20 percent of its customers do 95 percent of its business while another company finds that the top 20 percent of its customers do only 40 percent of its business. But in virtually every business, some customers are worth more than others. When the distribution of customer values is highly concentrated within just a small portion of the customer base, we say that the value skew of the customer base is steep.

Pareto Principle and Power-Law Distributions

When it comes to analyzing how customer values are distributed, the 80-20 Pareto principle does not result in a “normal” distribution, like a bell curve. (See Exhibit 5A.) The Pareto principle is a special case of what mathematicians call a power-law distribution, or a log-normal distribution. The key to understanding how a power law differs from a bell curve is to recognize that power laws go on and on with the same kind of distribution. (for this reason, we say that power-law distributions are “scale-free.”)

EXHIBIT 5A (a) Bell Curve or Normal Distribution and (b) Power-Law or Log- Normal Distribution

For instance, if customer lifetime values are distributed according to the 80-20 Pareto principle, so that the top 20 percent of customers account for 80 percent of the total value, then the 20 percent of that top 20 percent of customers will account for 80 percent of that 80 percent of value. In other words, just 4 percent of customers (20 percent of 20 percent) will account for 64 percent of a company’s total lifetime values (80 percent of 80 percent). Multiply it again and you’ll find that fewer than 1 percent of customers will account for more than 50 percent all customer lifetime value, and so forth.

It’s important to remember that all such distributions are still inherently random, and no random distribution of discrete quantities (e.g., individual customer lifetime values) will ever conform precisely to a particular mathematical formula. But it’s easy to be confused by the Pareto principle, because it represents a power law, while many of the natural phenomena we observe in everyday life are distributed according to the more intuitively understandable bell curve. Human height, for instance, is distributed according to a bell curve, while wealth is distributed according to a power law. If you walk down a crowded city street and catalog the different heights of the people you encounter, chances are you’ll see an occasional 6 foot 6 person or maybe even someone who is nearly 7 feet tall, but the odds of finding someone much taller than 7 feet 6 inches are vanishingly small. (You’ll also see one or two adults who are under 5 feet tall and maybe even an occasional person less than 4 feet 6 inches.)

Wealth, however, has no natural upper limit and is distributed according to a power law. Let’s suppose human height were distributed the same way personal wealth is distributed, with the average “height” of wealth being about 6 feet. If that were the case, then when you walked down the street you’d run into a few people in the 5- to 7-foot range, but many of the people you meet would actually be shorter than 3 feet tall, and the vast majority of them be only a few inches high! Every block or so, however, you’d encounter a couple of people 20 feet tall, and you’d likely see a 100-foot-tall person or even a 500-foot-tall person once in a great while. The longer you walk, the more likely you’ll see someone even taller than the last giant you encountered. If you happened to run into the two tallest people in the United States, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, they would each tower over the city, their heads more than a mile in the sky. Now, that would be a power-law distribution.

Power-law distributions characterize many kinds of measurable quantities that are based on networks, including the increasing proliferation of Internet-enabled social networks. As technology improves and continues to connect customers more and more closely together, power-law distributions can be expected to characterize things like the number of comments accumulated by different blogs, or the number of viewers of different YouTube videos, or the number of Twitter followers acquired by various users. As we read in Chapter 8, this is an important and more or less universal characteristic of social networks.

While LTV is the variable an enterprise wants to know, often a financial or statistical model is too difficult or costly to create. Instead, the enterprise may find some proxy variable to be nearly as useful. A proxy variable is a number, other than LTV, that can be used to rank customers in rough order of LTV, or as close to that order as possible, given the information and analytics available. A proxy variable should be easy to measure, but it obviously will not provide the same degree of accuracy when it comes to quantifying a customer’s actual value or ranking customers relative to each other.

For instance, many direct marketers use a proxy variable called RFM, for recency, frequency, and monetary value to rank-order their customers in terms of their value. The RFM model is based on individual customer purchase histories and incorporates three separate but quantified components:

1. Recency. Date of this customer’s most recent transaction

2. Frequency. How often this customer has bought in the past

3. Monetary value. How much this customer has spent in the most recent specified period

An airline, by contrast, might use a customer’s frequent-flier mileage as a proxy variable to differentiate one customer’s value from another’s. The mileage total for the last year, or the last two years, or some other period, will be a good indicator of the customer’s value, but it won’t be entirely accurate. For instance, it won’t tell the airline whether the customer usually flies in first class or in coach, and it won’t tell whether the customer always purchases the least expensive seat, frequently chooses to stay over on Saturdays, and takes advantage of various other pricing complexities and loopholes in order to guarantee always obtaining the lowest fare.

A proxy variable is, in effect, a representation of a customer’s value to the enterprise rather than a quantification of it. Nevertheless, proxy variables can be efficient tools for helping an enterprise rank its customers based on value, and with this ranking the company still can apply different strategies to different customers, based on their relative worth. Sophisticated LTV models can be expensive and time-consuming to create. If an enterprise is to explore and benefit from customer valuation principles, proxy variables that allow initial rank-ordering of customers by value are a good starting point.

The goal of value differentiation is not a historical understanding, but a predictive plan of action.

The goal of value differentiation is not a historical understanding but a predictive plan of action. RFM and other, similar, proxy-variable methods show that while differentiating among customers can be mathematically complex, it is still fundamentally a simple principle.

Customer Value Categories

Every customer has an actual value and a potential value. By visualizing the customer base in terms of how customers are distributed across actual and potential values, marketing managers can categorize customers into different value profiles, based on the type of financial goal the enterprise wants to achieve with each customer. For instance, one of a company’s goals for a customer with a high unrealized potential value would be to grow its share of customer (in order to realize some of this value), while one of the goals for a customer with low actual value and low potential value would be to minimize servicing costs. By thinking of individual customers both in terms of each one’s actual value (i.e., current LTV) and its unrealized potential values (i.e., growth potential), a company could array its customers roughly as shown in Exhibit 5.1.

EXHIBIT 5.1 Customer Value Matrix

Five different categories of customers are shown on this diagram, and an enterprise should have different strategic goals for each one:

1. Most valuable customers (MVCs). In the lower right quadrant of Exhibit 5.2, MVCs are the customers who have the highest actual value to the enterprise. This could be for any or all of a number of different reasons: They do the highest volume of business, yield the highest margins, stay more loyal, cost less to serve, and/or refer the most additional customers. MVCs are also customers with whom the company probably has the greatest share of customer. These may or may not be the traditional “heavy users” of a product; the MVC may, for example, fly a lot less often but always pays full fare for first-class tickets. The primary financial objective an enterprise will have for its MVCs is retention, because these are the customers likely giving the company the bulk of its profitability to begin with. In the airline business, these are the “platinum flyers” in the frequent-flyer program. In order to retain these customers’ patronage, an airline will give out bonus miles, offer special check-in lines, provide club benefits, and so forth. For a pharmaceutical company marketing prescription drugs to physicians, however, the most valuable customers may be those particular physicians who have the most influence over other physicians. (See “Customer Referral Value”)

2. Most growable customers (MGCs). In the upper left quadrant of Exhibit 5.2, MGCs are customers who have little actual value to the enterprise but significant growth potential. Here, of course, the enterprise’s financial objective is to realize some of that potential value. As a practical matter, these customers are often large-volume or high-profit customers who simply patronize a different company. MGCs are often, in fact, the MVCs of the enterprise’s competitors. So the company’s objective will be to change the dynamics in some way so as to achieve a higher share of each of these customers’ business. (Don’t forget, however, that the reverse is also true: Your own MVCs are your competitors’ MGCs.)

3. Low-maintenance customers. In the lower left quadrant are customers who have little current value to the enterprise and little growth potential. But they are still worth something (i.e., they are still profitable, at some level), and there are almost certainly a whole lot of them. The enterprise’s financial objective for low-maintenance customers should be to streamline the services provided them and to drive more and more interactions into more cost-efficient, automated channels. For a retail bank, for instance, these are the vast bulk of middle-market customers whose value will increase substantially if they can be convinced to use the bank’s online services rather than taking the time and attention of tellers at the branch.

4. Super-growth customers. In the upper right quadrant of Exhibit 5.2, many enterprises will have just a few customers who have substantial actual value and also a significant amount of untapped growth potential. This is more likely to be true for B2B firms than for consumer-marketing companies. If a company sells to corporate customers, it will likely have a few very large firms in its customer base that are giant, immense firms that already give the company a substantial amount of business. That is, they are likely already high-value customers, but they are so immense that they could still give the enterprise much more business. No matter what size B2B firm an enterprise is, if it sells to Microsoft, or Intel, or Nissan, or GE, or other corporate customers with similarly large financial profiles, chances are these customers are super-growth customers. The business objective here is not just to retain the business already achieved but to mine the account for more. There is one caveat, however: Sometimes super-growth customers, who obviously know that they represent immense opportunity for the companies they buy from, use their customer relationships to drive very hard bargains, squeezing margins down as they push volumes up. They can be merciless, because they know they are highly valuable to the firms they choose to buy from. (See “Dealing with Tough Customers.”)

5. Below-zeros (BZs). With very low or negative actual and potential values, BZs are customers who, no matter what effort a company makes, are still likely to generate less revenue than cost to serve. No matter what the firm does, no matter what strategy it follows, a BZ customer is highly unlikely ever to show a positive net value to the enterprise. Nearly every company has at least a few of these customers. For a telecommunications company, a BZ might be customer who moves often and leaves the last month or two unpaid at each address. For a retail bank, a BZ might be a customer who has little on deposit with the bank, but tends to use the teller window often. (Some banks in the United States estimate that as many as 40 to 50 percent of their retail customers are, in fact, BZs.) For a B2B firm, there can be a razor-thin difference between a super-growth customer and a BZ, because some giant business clients can threaten to drive margins down so low that they no longer cover the cost of servicing the account. The enterprise’s strategy for a BZ should be to create incentives either to convert the customer’s trajectory into a breakeven or profitable one (e.g., by imposing service charges for services previously given away for free) or to encourage politely the BZ to become someone else’s unprofitable customer.

This categorization of customers by their value profiles is fairly arbitrary, because it presumes customers can be split into just a few tight groups, based on actual and potential value. But whether the enterprise uses the MVC-MGC-BZ typology or not, what should be clear is that the enterprise should have different financial objectives for different customers, based on its assessment of the kind of value each customer is or is not creating for it already and what kind of value is possible.

Customer Referral Value

Obviously, some customers will refer new customers to an enterprise more frequently than others will, and this represents real value “created” by the referring customers. In most situations, a customer who comes into the enterprise’s franchise because of another customer’s referral is likely to be more satisfied with the service he or she receives, more loyal, and often significantly more valuable to the business than a customer who comes in through normal marketing or sales channels. This is only logical, because a friend’s recommendation is a highly trustworthy vote of confidence.

An enterprise should try to track customer referrals by individual customer, of course. For one thing, the enterprise needs to consider the fact of a referral in a customer’s transactional records, because referred customers as well as referring customers may tend to have different patterns of behavior and trajectories. In addition, the enterprise probably should thank the referring customer or provide other positive feedback that encourages additional referrals (although explicit monetary rewards are tricky here, as we discuss soon).

Fred Reichheld’s Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a compact metric designed to quantify the strength of a company’s word-of-mouth reputation among existing customers. Leading Bain consultant Reichheld suggests a business survey of its customers to ask how willing they would be to recommend the business or product to a friend or colleague, on a scale of 1 to 10. The NPS is then calculated by subtracting the percentage of “detractors,” who rate the likelihood anywhere from 1 to 6, from the percentage of “promoters,” who rate it 9 or 10. With research from Bain and Satmetrix, Reichheld claims that the resulting metric is positively correlated not only with customer loyalty but with a company’s growth prospects and its general financial performance. Reichheld also argues strongly that if a customer is willing to refer another customer, then he must be relatively more satisfied (and therefore more likely to remain loyal and valuable) himself as well.a As a very simple number based on a single question, NPS doesn’t offer a lot of diagnostic benefit—that is, by itself, it isn’t likely to say much about why a customer is or is not willing to recommend, but it has to be admired for its simplicity and practicality as well as its intuitive logic.

Significantly, calculating NPS requires subtracting detractors from promoters, which is an excellent idea, because customer dissatisfaction has been found to be a much better predictor of defection than customer satisfaction is of loyalty. Despite this fact, most companies that do track their customer satisfaction scores don’t bother trying to track dissatisfaction scores. This is a big mistake, because when customers talk about a company with other customers, it isn’t always positive. And negative word of mouth can be an insidious, destructive force all by itself, with a real effect on the financial value of the firm. (More about this in Chapter 8, when we discuss social media.)

At least one study more recent than Reichheld’s original NPS argument suggests that a customer’s actual referral value—that is, the true financial value of a customer’s referrals to an enterprise—is not well correlated with the value created by the customer’s own spending. In other words, although a customer may refer others to a business, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the customer herself spends much more than other customers. In a 2007 Harvard Business Review article, “How Valuable Is Word of Mouth?” the authors developed a comprehensive model for calculating the value of referrals, taking into account the likelihood that a referred customer might have become a customer anyway, even without the referral. They then applied their model to a sample set of customers taken from two different actual firms—one telecom company and one financial services firm. What they found was that the value created by customer referrals (CRVs) is a very significant component of overall customer lifetime values.b

So, for instance, a decile analysis of customer spending values (CSV) and customer referral values (CRV) for the telecom company’s customers would look like Exhibit 5B.

EXHIBIT 5B Decile Analysis of Customer Spending Values (CSV) and Customer Referral Values (CRV)

Rewarding customers with monetary incentives for referring other customers can be helpful sometimes in encouraging more referrals. This is the basis for the classic direct marketing strategy colloquially known as member-get-a-member and is a common feature even today of many airline frequent-flyer programs. Then there was the classic “Friends and Family” program launched by MCI, which was a remarkable success in the long-distance business in the 1990s. Name 10 friends or family members you make long-distance calls to, and if they become MCI customers, then everyone in your “circle” of friends and family will get a 10 percent discount off their calls to one another. More recently Sprint PCS has made it a practice to give any customer who refers another customer a service credit of $20, while Scottrade, the online brokerage firm, provides a few free stock trades to both referring and referred customers.c But the very best and likely most valuable referrals will come without requiring any monetary incentive. If a customer is very happy with a company’s product or service, then she is much more likely to see referring her friend to the company as doing the friend a favor. If, however, a financial incentive is offered, then (the customer might think) how confident can the company be in the quality of its product?

A highly successful online banking service in the United Kingdom, for instance, had a reputation for extremely good customer service. By its own analysis, this bank had customer satisfaction levels and “willingness to recommend” levels far above its nearest bricks-and-mortar banking competitors. Moreover, the bank had grown substantially in the past through customer recommendations. Citing Market & Opinion Research International, the firm’s own Web site claimed it was “the UK’s most recommended bank.”d

However, after a few years in business, it had apparently begun to wear out its welcome among many of its most loyal customers. One customer, for instance, reported that while he used to recommend the bank to his friends regularly, he had stopped doing so. Why? Because lately the bank had been sending him repeated, irrelevant solicitations by mail. A 12-year customer of the bank, he “never borrows,” but he and his wife now get about one solicitation a week for mortgages or loans. “I still bank there. It’s a good bank,” he says. “But I used to recommend [this bank] all the time to friends and others. I just thought I was doing a good turn for my friends by recommending it to them. But now they’re more like all the other banks out there—just trying to hustle me for more business. So I haven’t recommended them recently to anyone. Also, I know several other customers who feel the same way.”d And this may be one reason why this bank now pays its customers £25 for each new customer recommended to it. Put another way: The bank’s current lower customer experience levels required it to pay a fee for recommendations it formerly got for free.

aFred Reichheld, The Ultimate Question: Driving Good Profits and True Growth (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2006).

bThe authors defined customer lifetime values in terms of spending only, but we will call this “customer spending value,” while in our definition of “lifetime value” customer referrals are already included.

cV. Kumar, “How Valuable Is Word of Mouth?” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 10 (October 2007): 139–146.

dCustomer interview, November 12, 2003.

One large B2B company performed a value analysis of its customer base and arrayed its customers by actual value and unrealized potential value, creating the scattergram shown in Exhibit 5.2. Each of the dots in the exhibit represents a different business customer. The customers in this graph that occupy the long spike out to the right represent this company’s MVCs. Clearly, these are the customers giving the company the most business, and few of them have much unrealized potential value, because the company is getting the bulk of each one’s patronage in its category. Down in the lower left of the graph we can find a few customers who have less than zero actual value; these (of course) are this company’s BZ customers.

EXHIBIT 5.2 National Accounts’ Actual versus Unrealized Potential Value

The tall spike up the left-hand side of the scattergram represents this company’s MGCs. These are the customers who don’t give the firm much of their business right now but clearly have a great deal of business to give it, if they could be convinced to do so. You might note that the horizontal-vertical scales on this scattergram are not the same—that is, the vertical spike, if drawn to the same scale as the horizontal one, would soar up the page much farther than the illustration allows. And most of the customers in this vertical spike are the company’s competitor’s MVCs.

Is It Fair to “Fire” Unprofitable Customers?

As a company gets better at predicting actual and strategic value, it will become clear that just as 20 percent or so of its customers will likely account for the lion’s share of the firm’s profitability, another relatively small group of customers is likely to account for the lion’s share of service costs and transaction losses. It is not uncommon for a retail bank, for instance, to do a customer valuation analysis and learn that 110 percent of its profit comes from just the top 30 percent or so of its customers while the vast bulk of customers are either break-even or unprofitable for it, when considered individually. Other businesses have similar problems, although retail banking is probably one of the most extreme examples.

Because of traditional marketing’s heavy emphasis on customer acquisition, for many companies, it would be anathema even to suggest it, but the plain truth is that in many cases, a company will simply be more profitable if it were to get rid of some customers—provided, of course, that the customers it rids itself of are the ones who create losses without profit and who will likely continue to do so in the future.

Before leaping to the conclusion that this is unfair to customers, consider that it is the profitable customers who are, in effect, subsidizing the unprofitable ones. So “firing” unprofitable customers is not at all a hostile activity but one designed to make the overall value proposition fairer for all. Nevertheless, there are some important ground rules to follow when reducing the number of BZ customers at a company:

- However a company defines the value of a customer, the analysis must apply the same way to everyone. The company engaging in careful customer value differentiation does not care about skin color or gender, religion or political views. It cares only about each customer’s actual and potential value, and it acts accordingly. This may disadvantage some customers who have long ago abandoned loyalty in favor of coupon clipping or other price shopping but will appropriately reward the customers who are keeping the business in business.

- Some companies, such as utilities or telecommunications firms (or banks, in some countries), have enjoyed monopoly or near-monopoly status in the past through regulatory directive. Even if they are no longer government-sanctioned monopolies, as the established incumbents these firms are likely to continue to have universal service mandates that require them to serve any and all customers. Such firms still may choose to define value or customer profitability in a more sophisticated way than simple revenue minus cost of service. The telephone company that provides basic service to Aunt Matilda in a rural area cannot hope to make a “profit” on her, in the strictest financial sense, but rather than classifying her as a BZ customer, it should consider her part of the company’s mission to serve the community. Moreover, accomplishing this mission probably will be related to the company’s regulatory situation, and foreswearing such a customer might violate a legal requirement. For such a company, the real BZ customers would be those who move every few months and leave the final bill unpaid, requiring extra collection efforts; or who often cause mishaps with neighborhood lines; or who frequently change carriers or otherwise create excessive paperwork. These customers can be omitted from promotional mailing lists and other spending efforts. It’s okay to stop spending money trying to get a customer to generate a greater loss for the firm.

- Most important: Nothing about customer differentiation means treating anybody badly, ever. The enterprise that treats different customers differently will be required to maintain a consistently high “floor” of service that is the result of a fundamental recognition that customers are a twenty-first-century firm’s most valuable asset, and—by definition—the firm’s only source of revenue.

Nothing about customer differentiation means treating anybody badly. Ever.

Dealing with Tough Customers

Sometimes, because of the structure of an enterprise’s own industry or its distribution network, or simply because of the type of market it has to deal with, it will have to cope with very powerful customers—customers who have a great deal of negotiating leverage in their relationship with the vendors they buy from. Customers like these, while they may represent super-growth customers when considered in one light, are large enough that they can also demand and get highly favorable terms, in the form of lower prices, better service, priority delivery, and so forth. Occasionally such customers are so powerful that they may all but require an enterprise to lose money just to serve them. But extremely large customers also have prestigious names and are difficult for any company to resist.

In retailing, the giant mega-stores and category killers, such as Wal-Mart and Toys “R” Us, are very tough customers. In the high-tech field, companies that manufacture components in mature markets, such as microchips, must sell to tough customers like Dell and Hewlett-Packard. In the automotive category, almost all of the manufacturers are large, difficult to deal with, and obsessively concerned with price.

It’s important for a company to keep its perspective when serving “oppressive but necessary customers.”a In the first place, a firm can make rational decisions with respect to such relationships only if it understands its customers’ actual and potential values across the entire enterprise. But in addition, management at the enterprise should keep in mind that it really is a power struggle, so their firm must somehow develop more power for itself in the relationship. (Ironically, given all our discussion about “trust,” a tough customer will very likely trust the enterprise, but the enterprise will need to step carefully when dealing with this customer.) The goal, however, is to serve the customer’s best interests, and the enterprise won’t be able to do this if it has to give up on the relationship entirely because it has become too one-sided.

One former senior executive at Company X, a Fortune 100 technology firm, says that “[Company X] was always looked upon as the must-win account for every supplier—and we knew that well. So we routinely adopted very tough positions and made stringent demands.” According to this executive, the company’s “typical behavior” with respect to suppliers was to “work closely with that company, study them, and try to extract as much of the process and knowledge as possible, then fire the supplier and do it ourselves. Overall, being self-sufficient was always a key objective. A few companies managed to avoid this ultimate fate by continually innovating faster than we [at Company X] could absorb; so they maintained the ability to deliver new value each year.”

This is not unethical behavior on the part of a customer—far from it. It’s the policy that many large and powerful buyers follow, especially in highly competitive environments or during periods of rapid and potentially disruptive innovation. The problem, when selling to such a customer, is that it will be very difficult to increase profitability or even to maintain it. It will be nearly impossible to establish any kind of loyalty or to protect margins—but that is in fact the purpose behind the customer’s behavior in the first place. When dealing with suppliers, this kind of customer wants to use its power to hammer its costs down; and powerful firms have powerful hammers.

Sometimes an enterprise can maintain loyalty and protect its margins with tough customers by perpetually innovating new products or services, staying ahead of the customers themselves. Magna International sells automobile parts to all the world’s giant auto companies. Automotive companies are renowned for their tight-fistedness, their tough price negotiations, and their buying power. This is a brutal environment for a seller, but Magna is an innovative firm. With 238 manufacturing operations and 79 product-development, engineering, and sales centers employing 72,525 people around the world,b Magna is a large company—but it is still at a disadvantage when it comes to selling to most of its gigantic customers.

Magna set up its Magna Steyr operation specifically to cater to the most important, unmet needs of these auto giants.c As the auto business has matured, it has seen increased fluctuations in demand for particular models. The car companies themselves are often unable to cope with these demands, and a “hot” model might be sold out for months at a time. Rather than selling auto parts at arm’s length, the Magna Steyr division brings together all the capabilities required to manufacture cars, from parts to engineering, design, and production. For example, when demand for the new Mercedes M-Class SUV exceeded the capabilities of Mercedes’ Tuscaloosa assembly line in late 1998, Magna Steyr was producing additional M-Class vehicles for Daimler-Chrysler on its own assembly line in Graz, Austria, within just nine months. This kind of service can help a firm protect its margins even with the toughest customers. And as a strategic asset, Magna Steyr’s capabilities provide the company with a sustainable competitive advantage over its own competitors.

Sometimes an enterprise can deal effectively with tough customers by devising some service or offering that is customized to each customer’s own needs, or that is available only because of the enterprise’s own, larger breadth of experience or knowledge of the marketplace. In the commercial explosives business, Orica is a global company serving a large number of mining companies and quarry operators.d Quarry operators want their blasts to break rocks up into pieces of optimal size. An ineffective blast might leave the rock in chunks too large to be processed in an economically viable way. But as many as 20 different variables have to be considered when calibrating an explosive blast, and each quarry’s ability to experiment with these parameters is limited. Because of its size, and the many different mines and quarries Orica deals with, the company can collect a great deal of information from around the world, cataloging input parameters and blast results for a wide variety of situations. As a result, Orica has developed a sound understanding of blasting techniques and now offers to take charge of the entire blasting process for a customer, selling a service contract for broken rocks of a specific size. This service has two advantages for Orica’s customers.

1. They minimize the risk of poorly executed blasts. With an Orica contract, a customer, together with Orica, basically establish a “floor price” for correctly broken-up rock.

2. Many of a customer’s fixed costs, such as equipment for drilling and employees to manage the process, now become variable costs, which makes it that much easier for the company to manage each separate blasting project for its own customers. What makes this service useful to customers is the fact that Orica is uniquely positioned to compile information on blast techniques and parameters in a wide variety of situations. Any single one of its customers would have a great deal of difficulty duplicating this expertise.

Four principle tactics can be used to improve and maintain the value of even the toughest customers, and each of these tactics involves increasing the enterprise’s relative power, uniqueness, or indispensability in the relationship:

1. Customization of services or products. An enterprise can build high-end, customized services around the more commodity-like products or services it sells, which creates switching costs that increase a customer’s willingness to remain loyal, rather than bidding out the contract at every opportunity. Ideally, the enterprise will lock the customer into a Learning Relationship, but most tough customers will be wary of allowing such relationships to develop. The trick here is for the company to ensure that whatever high-end services are developed can be duplicated only by its competitors with great effort, even if they are instructed in advance (and they almost certainly will be by this tough customer!). This was Orica’s strategy in offering “broken rock of a certain size” to customers rather than simply selling them explosives.

2. Perpetual, cost-efficient innovation. To the extent that an enterprise can stay ahead of its tough customer with innovative product or service ideas, it will always have something to sell. The organizational mission must center on being nimbler, more creative, and cost-efficient—all at the same time. But the value such a firm is really bringing to the customer here is innovation, not the products themselves. Many tough customers will do their best to absorb a seller’s innovation in order to do it themselves or perhaps even to disseminate it to the seller’s own competitors, in order to maintain vigorous competition and low prices. In either case, the customers’ motive is to regain their negotiating power in dealing with the seller. So perpetual innovation is just that—perpetual. If a company can keep the wheels spinning fast enough, and provided that it doesn’t lose control of costs, it can safely deal with very tough buyers. This is the strategy behind Magna Steyr’s relationship with auto company customers.

3. Personal relationships within the customer organization. In the end, businesses have no brains, and they make no decisions. Only the people within a business make decisions, and people are both rational and emotional by nature. Therefore, the individuals within the enterprise need to have personal relationships with the individuals within the customer’s organization. In the high-tech or automotive arena, this might mean developing relationships with the engineers within a customer’s organization who are responsible for designing the company’s components into the final product. In the retailing business, it could mean developing relationships with the regional merchandising managers who get promoted based on the success of the programs the enterprise helps organize for them.

4. Appeals directly to end users. A highly desirable brand or a completely unique product in heavy demand by the customer’s own customers will pull a seller’s products through the customer’s own organization more easily. The “Intel Inside” advertising campaign is designed to create pull-through for Intel. When Mattel offers Toys “R” Us an exclusive arrangement for particular configurations, or products with brand names such as “Barbie” or “Transformers” or “Harry Potter,” it is making itself indispensable to this very tough customer. Similarly, any sort of information system or added service that saves time or effort for the end user can also be expected to put pressure on a tough customer. Dell’s Web pages for enterprise customers not only save money for the customers but also give Dell a direct, one-to-one relationship with the executives who actually have the Dell computers on their desks.

Management should never forget, however, that selling to a tough customer is a deliberate decision, and it’s possible sometimes that this decision will be made for the wrong reason. There are almost always choices to be made when thinking about the types of customers to serve, but often companies focus on the very large, most visible and “strategic” customers (i.e., tough customers), in the erroneous belief that simply because of their size they will be the most profitable. But, according to the ex-technology executive from Company X:

Overall, I don’t think that we at [Company X] are all that different from most category-dominant companies. These guys know they’re good and can get away with demanding just about anything. What many suppliers discover sooner or later is that despite the outward allure of serving a company like ours, once you actually win the business, the long-term payoff can be too painful to harvest. It was not unusual for a supplier to “fire” us as a customer by politely declining to bid on the next program.

aThanks to Bob Langer, Tom Spitale, Vernon Tirey, Steve Skinner, and Lorenz Esguerra for their perspectives on the issues in this section on “tough customers.” The term oppressive-but-necessary customers is from Tom Spitale.

bAvailable at: www.magna.com/magna/en/media/facts/default.aspx; accessed March 2010.

cFor more about Magna, see Mark Vandenbosch and Niraj Dawar, “Beyond Better Products: Capturing Value in Customer Interactions,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 4 (Summer 2002): 35–42.

dSee www.oricaminingservices.com, accessed March 29, 2010.

Managing the Mix of Customers

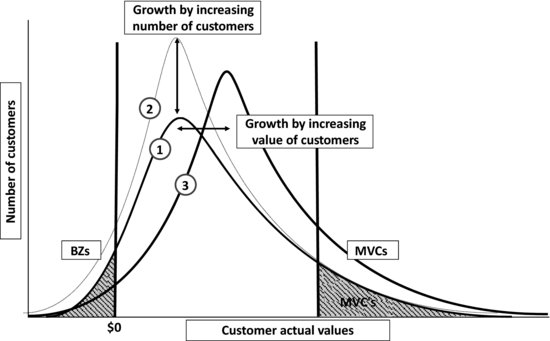

One way to think about the process of managing customer relationships is that the enterprise is attempting to improve its situation not just by adding as many new customers as possible to the customer base but also by managing the mix of customers it deals with. It wants to add to the number of MVCs, create more profitability from its MGCs, and minimize its BZs. An enterprise in this situation could choose either to emphasize adding new customers to its customer base or (instead or in addition) to increase the values of the customers in its customer base. So imagine if an enterprise were to plot the distribution of its customer values on a chart, as in Exhibit 5.3, with actual values of customers shown across the bottom axis and the number of customers shown up the vertical axis.

EXHIBIT 5.3 Managing the Mix of Customers