What Is Performance Appraisal?

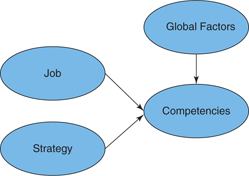

Performance appraisal , as shown in Figure 7.1, includes the identification, measurement, and management of human performance in organizations.1

FIGURE 7.1 A Model of Performance Appraisal

-

▪ Identification means determining what areas of work the manager should be examining when measuring performance. Rational and legally defensible identification requires a measurement system based on job analysis, which we explored in Chapter 2 . The appraisal system, then, should focus on performance that affects organizational success rather than performance-irrelevant characteristics such as race, age, or sex.

-

▪ Measurement, the centerpiece of the appraisal system, entails making managerial judgments of how “good” or “bad” employee performance was. Performance measurement must be consistent throughout the organization. That is, all managers in the organization must maintain comparable rating standards.2

-

▪ Management is the overriding goal of any appraisal system. Appraisal should be more than a past-oriented activity that criticizes or praises workers for their performance in the preceding year. Rather, appraisal must take a future-oriented view of what workers can do to achieve their potential in the organization. This means that managers must provide workers with feedback and coach them to higher levels of performance.

The Uses of Performance Appraisal

Organizations usually conduct appraisals for administrative and/or developmental purposes.3 Performance appraisals are used administratively whenever they are the basis for a decision about the employee’s work conditions, including promotions, termination, and rewards. Developmental uses of appraisal, which are geared toward improving employees’ performance and strengthening their job skills, include providing feedback, counseling employees on effective work behaviors, and offering them training and other learning opportunities.

Performance appraisal offers great potential for a variety of uses, ranging from operational to strategic purposes.4 If done effectively, performance appraisal can be the key to developing employees and improving their performance. In addition, it provides the criteria against which selection systems are validated and is the typical basis on which personnel decisions, such as terminations, are legally justified. Further, performance appraisal makes the strategy of an organization real. For example, performance measures that assess courtesy and care can make a stated competitive strategy based on customer service very tangible to employees.

Despite the many uses of performance appraisals, companies struggle to realize the potential in their performance appraisal systems.5 If managers aren’t behind the system and can’t see its value, it is little wonder that workers also don’t see the value in it. To be effective, the performance appraisal system may require considerable time and effort of managers and may require employees to gather information and receive feedback. Unfortunately, some managers do not take the task seriously or do not have the skills needed to do a good job of evaluating performance and providing feedback. Some employees do not calmly accept the feedback. Others may become frustrated with an ineffective performance appraisal system and end up believing that the system is unfair and doesn’t matter.

Although performance appraisal systems can have problems and are the target of many criticisms, employees still want performance feedback, and they would like to have it more frequently than the typical once-a-year performance evaluation.6 Although more frequent formal appraisal can be positive, the practical reality is that informal appraisal, including feedback and discussion with workers, should occur on a continuous basis.

If appraisal is not done well—if, for instance, performance is not measured accurately and feedback is poorly given—the costs of conducting the appraisal may exceed its potential benefits.7 It makes good business sense to engage in a practice only if the benefits exceed the cost. Some people take the position that performance appraisal should not be done at all.8 From this perspective, the practice of performance appraisal is staunchly opposed as a hopelessly flawed and demeaning method of trying to improve performance.9 Thus, performance appraisal should be eliminated as a practice in organizations because of the problems and errors in evaluating performance.10 One basis for the position against doing performance appraisal is the quality philosophy11 that performance is mainly due to the system and that any performance differences among workers are random.

Although there is selected opposition, the vast majority of organizations conduct performance appraisal. Figure 7.2 lists several reasons, from both the employer’s and employee’s perspectives, why appraisal is valuable despite the criticisms that have been leveled against it.

Identifying Performance Dimensions

The first step in the performance appraisal process (see Figure 7.1) is identifying what is to be measured. Consider the following example:

As part of her job as team manager, Nancy has to allocate raises based on performance. She decides to take a participative approach to deciding which aspects, or dimensions , determine effective job performance. In a meeting, she and her team start generating dimensions of performance. One of the first suggestions is the quality of work done. However, Nancy realized that some of the workers she supervises took three times longer than others to complete assignments, so she offered quantity of work performed as another dimension. One worker volunteered that how well someone interacted with peers and “customers” inside the organization was pretty important. The team added interpersonal effectiveness as another performance dimension.

Employer Perspective

Despite imperfect measurement techniques, individual differences in performance can make a difference to company performance.

Documentation of performance appraisal and feedback may be needed for legal defense.

Appraisal provides a rational basis for constructing a bonus or merit system.

Appraisal dimensions and standards can help to implement strategic goals and clarify performance expectations.

Providing individual feedback is part of the performance management process.

Despite the traditional focus on the individual, appraisal criteria can include teamwork and the teams can be the focus of the appraisal.

Employee Perspective

Performance feedback is needed and desired.

Improvement in performance requires assessment.

Fairness requires that differences in performance levels across workers be measured and have an effect on outcomes.

Assessment and recognition of performance levels can motivate workers to improve their performance.

FIGURE 7.2

The Benefits of Performance Appraisal

Sources:Based on Cardy, R. L., and Carson, K. P. (1996). Total quality and the abandonment of performance appraisal: Taking a good thing too far? Journal of Quality Management, 1, 193–206; Heinze, C. (2009). Fair appraisals. Systems Contractor News, 16, 36–37; Tobey, D. H., and Benson, P. G. (2009). Aligning performance: The end of personnel and the beginning of guided skilled performance. Management Revue, 20, 70–89.

In the next two sections, we explain the issues and challenges involved in the first two steps of performance appraisal: identification and measurement. We conclude the chapter by discussing some of the key issues involved in managing employee performance.

Raising and considering additional work dimensions might continue until Nancy and her team have identified perhaps six or eight dimensions they think adequately capture performance. The team might also decide to make the dimensions more specific by adding definitions of each and behavioral descriptions of performance levels.

As you have probably realized, t he process of identifying performance dimensions is very much like the job-analysis process described in Chapter 2 . In fact, job analysis is the mechanism by which performance dimensions should be identified.

What is measured should be directly tied to what the business is trying to achieve,12 because the performance appraisal process needs to add value to the business and not be done simply as a measurement exercise. Many organizations identify performance dimensions based on their strategic objectives. This approach makes sure that everyone is working together toward common goals.13

An increasingly popular approach to identifying performance dimensions focuses on competencies , the observable characteristics people bring with them in order to perform the job successfully.14 In order to make adequate evaluations, it is important to define competencies as observable characteristics, rather than as underlying and unseen characteristics (see the discussion and difficulties associated with personality traits as performance measures in the following section). The set of competencies associated with a job is often referred to as a competency model . An example of a competency model is presented in the Manager’s Notebook, “Competencies in a Global Workplace.”

Source:Ambrophoto/Shutterstock.

Measuring Performance

To measure employee performance, managers can assign numbers or a label such as “excellent,” “good,” “average,” or “poor.”15 Whatever system is used, it is often difficult to quantify performance dimensions. For example, “creativity” may be an important part of the advertising copywriter’s job. But how exactly can we measure it—by the number of ads written per year, by the number of ads that win industry awards, or by some other criterion? These are some of the issues that managers face when trying to evaluate an employee’s performance.

Measurement Tools

Managers today have a wide array of appraisal formats from which to choose. Here we discuss the formats that are most common and consider their legal defensibility. Appraisal formats can be classified in two ways: (1) by the type of judgment that is required (relative or absolute) and (2) by the focus of the measure (trait, behavior, or outcome).

Relative and Absolute Judgments

Appraisal systems based on relative judgment ask supervisors to compare an employee’s performance to the performance of other employees doing the same job. Providing a rank order of workers from best to worst is an example of a relative approach. Another type of relative judgment format classifies employees into groups, such as top third, middle third, and lowest third.

Relative rating systems have the advantage of forcing supervisors to differentiate among their workers. Without such a system, many supervisors are inclined to rate everyone the same, which destroys the appraisal system’s value. For example, one study that examined the distribution of performance ratings for more than 7,000 managerial and professional employees in two large manufacturing firms found that 95 percent of employees were crowded into just two rating categories.

Most HR specialists believe the disadvantages of relative rating systems outweigh their advantages.16 First, relative judgments (such as ranks) do not make clear how great or small the differences between employees are. Second, such systems do not provide any absolute information, so managers cannot determine how good or poor employees at the extreme rankings are. For example, relative ratings do not reveal whether the top-rated worker in one work team is better or worse than an average worker in another work team. This problem is illustrated in Figure 7.3. Marcos, Jill, and Frank are the highest-ranked performers in their respective work teams. However, Jill, Frank, and Julien are actually the best overall performers.

Team 1 Team 2 Team 3 Actual Ranked Work Ranked Work Ranked Work 10 (High) Jill (1) Frank (1) 9 Julien (2) 8 Tom (2) Lisa (3) 7 Marcos (1) Sue (3) 6 Uma (2) 5 4 Joyce (3) Greg (4) 3 Bill (4) Ken (5) Jolie (4) 2 Richard (5) Steve (5) 1 (Low)

FIGURE 7.3

Rankings and Performance Levels Across Work Teams

Third, relative ranking systems force managers to identify differences among workers where none may truly exist.17 This can cause conflict among workers if and when ratings are disclosed. Finally, relative systems typically require assessment of overall performance. The “big picture” nature of relative ratings makes performance feedback ambiguous and of questionable value to workers who would benefit from specific information about the various dimensions of their performance. For all these reasons, companies tend to find relative rating systems most useful only when there is an administrative need (for example, to make decisions regarding promotions, pay raises, or terminations).18

Unlike relative judgment appraisal formats, absolute judgment formats ask supervisors to make judgments about an employee’s performance based solely on performance standards. Comparisons to the performance of coworkers are not made. Typically, the dimensions of performance deemed relevant for the job are listed on the rating form, and the manager is asked to rate the employee on each dimension. An example of an absolute judgment rating scale is shown in Figure 7.4.

FIGURE 7.4

Sample of Absolute Judgment Rating Scale

Theoretically, absolute formats allow employees from different work groups, rated by different managers, to be compared to one another. If all employees are excellent workers, they all can receive excellent ratings. In addition, because ratings are made on separate dimensions of performance, the feedback to the employee can be more specific and helpful. Absolute formats are also viewed as more fair than relative formats.19

Although often preferable to relative systems, absolute rating systems have their drawbacks. One is that all workers in a group can receive the same evaluation if the supervisor is reluctant to differentiate among workers. Another is that different supervisors can have markedly different evaluation standards. For example, a rating of 6 from an “easy” supervisor may actually be lower in value than a rating of 4 from a “tough” supervisor. But when the organization is handing out promotions or pay increases, the worker who received the 6 rating would be rewarded.

Nonetheless, absolute systems do have one distinct advantage: They avoid creating conflict among workers. This, plus the fact that relative systems are generally harder to defend when legal issues arise, may account for the prevalence of absolute systems in U.S. organizations.

It is interesting to note, though, that most people do make comparative judgments among both people and things. A political candidate is better or worse than opponents, not good or bad in an absolute sense. If comparative judgments are the common and natural way of making judgments, it may be difficult for managers to ignore relative comparisons among workers.

Trait, Behavioral, and Outcome Data

In addition to relative and absolute judgments, performance measurement systems can be classified by the type of performance data on which they focus: trait data, behavioral data, or outcome data.

Trait appraisal instruments ask the supervisor to make judgments about traits, worker characteristics that tend to be consistent and enduring. Figure 7.5 presents four traits that are typically found on trait-based rating scales: decisiveness, reliability, energy, and loyalty. Although some organizations use trait ratings, trait ratings have been criticized for being too ambiguous20 and for leaving the door open for conscious or unconscious bias. In addition, because of their ambiguous nature trait ratings are less defensible in court than other types of ratings.21 Definitions of reliability can differ dramatically across supervisors, for example, and the courts seem to be sensitive to the “slippery” nature of traits as criteria.

FIGURE 7.5

Sample Trait Scales

Assessment of traits also focuses on the person rather than on the performance, which can make employees defensive. This type of person-focused approach is not conducive to performance development. Measurement approaches that focus more directly on performance, either by evaluating behaviors or results, are generally more acceptable to workers and more effective as development tools. It is not that personality traits are not important to performance; the problem is with using a broad person characteristic, such as reliability, as a performance measure. To categorize an employee as “unreliable” will likely make the worker defensive, and the basis for the assessment and how to improve may not be clear. It would be preferable to assess and provide feedback on more observable and performance-relevant measures, such as number of times the employee has been late, the number of missed deadlines, and so on.

Behavioral appraisal instruments focus on assessing a worker’s behaviors. That is, instead of ranking leadership ability (a trait), the rater is asked to assess whether an employee exhibits certain behaviors (for example, works well with coworkers, comes to meetings on time). Probably the best-known behavioral scale is the Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scale (BARS). Figure 7.6 is an example of a BARS scale used to rate the effectiveness with which a department manager supervises his or her sales personnel. Behaviorally based rating scales are developed with the critical-incident technique. We describe the critical-incident technique in the Appendix to this chapter.

The main advantage of a behavioral approach is that the performance standards are unambiguous and observable. Unlike traits, which can have many meanings, behaviors across the range of a dimension are included directly on the behavioral scale. Because behaviors are unambiguous and based on observation, BARS and other behavioral instruments are more legally defensible than trait scales, which often use such hard-to-define adjectives as “poor” and “excellent.” Behavioral scales also provide employees with specific examples of the types of behaviors to engage in (and to avoid) if they want to do well in the organization, and they encourage supervisors to be specific in their performance feedback. Having behavioral examples can make clear to employees how to enact organizationally prescribed values that may otherwise be unclear to them. For example, acting with integrity or being ethical may sound like great concepts, but workers may be unclear about what these concepts should mean for their day-to-day work performance. The Manager’s Notebook, “Make Ethics Part of Appraisal,” suggests how you can operationalize these concepts. Finally, both workers and supervisors can be involved in the process of generating behavioral scales.22 This is likely to increase understanding and acceptance of the appraisal system.

FIGURE 7.6

Sample BARS Used to Rate a Sales Manager

Source:Campbell, J. P., Dunnette, M. D., Arvey, R. D., and Hellervik, L. V. (1973). The development and evaluation of behaviorally based rating scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 15–22. © 1973 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK Make Ethics Part of Appraisal

Ethics/Social Responsibility

Performance appraisal is typically focused on tasks and business accomplishments. However, how duties are carried out and how goals are achieved can be critically important in organizations. Specifically, the ethical conduct of employees can be an important issue, but it is often not directly measured. Ethical conduct is often identified as a guiding value at the organizational level. But how does this value translate into everyday performance on the job? Many organizations have codes of ethics, but it may not be clear to employees how it should translate into how they perform their jobs. For example, a code emphasizing integrity and fairness may sound great, but what the code should mean for how the worker carries out his or her tasks may be ambiguous.

Including ethics in the appraisal of performance sends a clear signal about the importance of ethics in the organization. Taking a behavioral approach to the assessment of ethical performance can make clear the types of actions workers should and shouldn’t do.

Source:Image Source/Getty Images.

The dimensions described here are examples of ethical characteristics that have been found to occur in organizations. A positive and negative behavioral example is provided for each of these dimensions of ethical performance. These behavioral examples are general and provide only a broad behavioral description of each dimension. The behavioral descriptions would probably be most useful if they were customized for each organization’s setting.

| Dimensions | General Behavioral Examples |

|---|---|

| Misrepresentation |

+ This worker accurately states work situations. − This worker misconstrues work situations. |

| Information Sharing |

+ This worker openly shares information with coworkers. − This worker withholds information from coworkers. |

| Collegiality |

+ This worker supports colleagues and provides a positive influence. − This worker attacks colleagues and is a negative influence. |

| Adherence to Work Rules |

+ This worker follows standards for work processes. − This worker does not follow standards for work processes. |

Behavioral systems are not without disadvantages, however. Developing them can be very time consuming, easily taking several months. Another disadvantage is their specificity. The points, or anchors, on behavioral scales are clear and concrete, but they are only examples of behaviors a worker may exhibit. Employees may never exhibit some of these anchor behaviors, which can cause difficulty for supervisors at appraisal time. Also, significant organizational changes can invalidate behavioral scales. For example, computerization of operations can dramatically alter the behaviors that workers must exhibit to be successful. Thus, the behaviors painstakingly developed for the appraisal system could become useless or, worse, operate as a drag on organizational change and worker adaptation. To avoid this problem of obsolescence, behavioral examples could be developed that reflect general performance capabilities rather than very job-specific task performance. Outcome appraisal instruments ask managers to assess the results achieved by workers, such as total sales or number of products produced. The most prevalent outcome approaches are management by objectives (MBO) 23 and naturally occurring outcome measures. MBO is a goal-directed approach in which workers and their supervisors set goals together for the upcoming evaluation period. The rating then consists of deciding to what extent the goals have been met. With naturally occurring outcomes, the performance measure is not so much discussed and agreed to as it is handed to supervisors and workers. For example, a computerized production system used to manufacture cardboard boxes may automatically generate data regarding the number of pieces produced, the amount of waste, and the defect rate.

MANAGER’S NOTEBOOK Competencies in a Global Workplace

Global

Competencies needed to adequately perform in an organization can go beyond being able to complete tasks. Global aspects of today’s organizations can mean that additional competencies are needed. For example, working with customers from various parts of the world or working with fellow employees on virtual teams from around the globe can require additional skills.

Competencies are often identified based on either an analysis of what is done on a job or based on the core mission and strategy of an organization. In the case of basing competencies on job requirements, the focus begins with what needs to be done. Based on what the employee needs to do on the job, competencies are identified. For example, for a job that requires assembly of parts, a manager or human resources representative might identify mechanical skill as a core competency area.

Competencies can also be based on the strategy of the firm. An organization might, for example, set its sights on becoming known for its customer service, even though its current emphasis has been on manufacturing. Basing competencies on the current jobs would not capture this customer-service focus. However, basing competencies on the strategy of the organization will help move it closer to reaching that customer service target. Identifying customer service behaviors as a competency that will be measured and developed as part of the performance appraisal system can make the strategic goal of competing on customer service a reality for the business.

Globalization in the business world is also a source for competencies in many organizations. Certainly, having the competencies to perform the required tasks or the competencies that have strategic value is necessary if employees are to add value to the business. Simply being able to operationally perform tasks is not the whole story—it’s also how the tasks are carried out and knowing when a situation calls for different approaches. Differences in culture can be one of those key situational factors that need to be taken into account. People from different countries or backgrounds can differ in their beliefs, experiences, and values. These differences can affect a wide variety of work-related issues. In the extreme, differences in language can make communication difficult and negatively impact areas such as sales and decision making in the organization. Less dramatic, but also important, cultural differences can also impact styles of communication, priorities, and preferred styles of working. For example, people from more individualistic cultures, such as the United States, Australia, and United Kingdom, would generally be more responsive to performance feedback that focuses on their individual contributions. In contrast, people from more collectivist cultures, such as China and Singapore, would look for feedback that focuses on how their work team is doing as a whole.

In situations where jobs include working with customers or fellow employees from diverse backgrounds, cultural competency may be as important as job- or strategy-based competencies. The sources of competencies are summarized in the following illustration.

The ability to do the tasks that are part of the job and the ability to contribute to the strategic mission of the organization are core competencies. In today’s global environment, awareness of cultural differences and the ability to take those differences into account can also be critical competencies.

The outcome approach provides clear and unambiguous criteria by which worker performance can be judged. It also eliminates subjectivity and the potential for error and bias that goes along with it. In addition, outcome approaches provide increased flexibility. For example, a change in the production system may lead to a new set of outcome measures and, perhaps, a new set of performance standards. With an MBO approach, a worker’s objectives can easily be adjusted at the beginning of a new evaluation period if organizational changes call for new emphases. Perhaps the most important thing is that outcomes can easily be tied to strategic objectives.24

Are outcome-based systems, then, the answer to the numerous problems with the subjective rating systems discussed earlier? Unfortunately, no. Although they are objective, outcome measures may give a seriously deficient and distorted view of worker performance levels. Consider an outcome measure defined as follows: “the number of units produced that are within acceptable quality limits.” This performance measure may seem fair and acceptable. However, when the machine is not running properly, it can take several hours—sometimes an entire shift—to locate the problem and resolve it. If you were a manager, you would put your best workers on the problem. But consider what would happen to their performance. Your best workers could actually end up looking like the worst workers in terms of the amount of product produced.

This situation actually occurred at a manufacturer of automobile components.25 Management concluded that supervisors’ subjective performance judgments were superior to objective outcome measures. The objective numbers were deficient measures of performance and didn’t accurately portray who were the better and poorer workers. Some of the best workers were assigned to difficult situations and were given responsibility to resolve problems with machinery, giving these workers poor productivity numbers. The objective data couldn’t take these factors into account, but the supervisors could consider difficulty of assignments when assessing employee performance. Another potential difficulty with outcome-based performance measures is the development of a “results at any cost” mentality.26 Using objective measures has the advantage of focusing workers’ attention on certain outcomes, but this focus can have negative effects on other facets of performance. For example, an organization may use the number of units produced as a performance measure because it is fairly easy to quantify. Workers concentrating on quantity may neglect quality and follow-up service to the long-term detriment of the organization. Likewise, a “results at any price” mentality can lead workers to disregard ethics in the conduct of their job so that goals are achieved.27 Although objective goals and other outcome measures are effective for increasing performance levels, these measures may not reflect the entire spectrum of performance.28

Measurement Tools: Summary and Conclusions

Our discussion so far makes it clear that there is no single best appraisal format. Figure 7.7 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of each approach in the areas of administration, development, and legal defensibility. The choice of appraisal system should rest largely on the appraisal’s primary purpose.

For example, say that your main management concern is obtaining desired results. An outcome approach would be best for this purpose. However, when outcomes are not adequately achieved, further evaluation may be needed to diagnose the problem.

Empirical evidence suggests that the type of tool does not make that much difference in the accuracy of ratings.29 If formats do not have much impact on ratings, what does? Not surprisingly, it’s the person doing the rating. Characteristics such as the rater’s intelligence, familiarity with the job,30 and ability to separate important from unimportant information31 influence rating quality. Thus, the person doing the rating is an important determinant of the quality of ratings.

CRITERIA Appraisal Format Administrative Use Developmental Use Legal Defensibility Absolute 0 + 0 Relative + + + − Trait + − − − Behavior 0 + + + Outcome 0 0 + − − Very poor − Poor 0 Unclear or mixed + Good + + Very good

FIGURE 7.7

Evaluation of Major Appraisal Formats

Who does the rating is commonly referred to as the source of the appraisal. The most common source is the worker’s direct supervisor. However, other sources can provide unique and valuable perspectives to the performance appraisal process. Self, peers, subordinates, and even customers are increasingly common sources of appraisal.

Self-review , in which workers rate themselves, allows employees input into the appraisal process and can help them gain insight into the causes of performance problems. For example, there may be a substantial difference in opinion between a supervisor and an employee regarding one area of the employee’s evaluation. Communication and possibly investigation are warranted in such a case. In some situations, people can find themselves having to rely on self-appraisal as a guide to managing performance.

In a peer review , workers at the same level of the organization rate one another. In a subordinate review , workers review their supervisors.

In addition to feedback from within the organization, some companies look to customers as a valuable source of appraisal. Traditional top-down appraisal systems may encourage employees to perform only those behaviors that supervisors see or pay attention to. Thus, behaviors that are critical to customer satisfaction may be ignored.32

Indeed, customers are often in a better position to evaluate the quality of a company’s products or services than supervisors are. Supervisors may have limited information or a limited perspective, whereas internal and external customers often have a wider focus or greater experience with more parts of the business.

The combination of peer, subordinate, and self-review and sometimes customer appraisal is termed 360° feedback . A 360° system can offer a well-rounded picture of an employee’s performance, one that is difficult to ignore or discount, because it comes from multiple perspectives. Many organizations are now employing technology to make 360° appraisal an efficient and cost-effective system.