3

Context of change

The context of change relates to dynamism in external and internal relationships, as well as organizational responses to them (Armenakis & Bedeian, 1999), or temporality of actions (Heracleous & Barrett, 2001; Stouten, Rousseau, & De Cremer, 2018). It is hardly surprising that large-scale change efforts, such as acquisitions, impact relations with internal and external interest groups. Still, research mainly considers one stakeholder at the time. The context of change surrounding acquisitions is also likely to be idiosyncratic (e.g., Casciaro & Piskorski, 2005), so we focus on summarizing stakeholders that firm managers need to consider. For example, acquisitions change relationships with internal and external stakeholders that can be inconsistent with prior routines (Stensaker, Falkenberg, & Gronhaug, 2008), and this can contribute to employee resistance (Sonenshein, 2010). As a result, most research on internal disruptions to organizations and steps managers can take to mitigate its negative impacts (Meglio et al., 2015). However, acquisitions also change relationships with competitors (e.g. King & Schriber, 2016), suppliers (e.g. Kato & Schoenberg, 2014), and customers (e.g. Degbey, 2015; Rogan, 2013). We also review research on options for communicating with stakeholders.

Stakeholders

Acquiring and target firms operate in industries at different stages along the industry lifecycle (Bauer, Schriber, Degischer, & King, 2018) that also need to consider competitors (e.g. King & Schriber, 2016), suppliers (e.g. Kato & Schoenberg, 2014), and customers (e.g. Degbey, 2015; Rogan, 2013). Second, while acquisitions considered at one level affect firms, they also affect and are affected by various other stakeholders (Hitt, Harrison, & Ireland, 2001). Consequently, this chapter focuses on the external and internal context using a stakeholder perspective of acquisitions. Understanding stakeholder impacts from an acquisition has gained increased appreciation in achieving acquisition success or minimizing its challenges (King & Taylor, 2012). In the following sections, we develop insights from research on different stake-holders that firms need to consider when contemplating an acquisition. Figure 3.1 displays common stakeholders along the acquisition process.

Figure 3.1 Stakeholders impacting acquisitions

Shareholders

The primary perspective taken in acquisition research is that of an acquiring firm’s shareholder wealth gains (Meglio & Risberg, 2011), and owners both influence and are affected by acquisitions. Shareholders are considered by many as the primary stakeholder of a firm and managers often conduct road shows to solicit shareholder acceptance of an acquisition (Brauer & Wiersema, 2012). Another consideration is that over 90 percent of acquisitions have lawsuits filed with the majority of lawsuits filed by shareholders (Secher & Horley, 2018). Wide variance in the premiums paid for target firms (Laamanen, 2007) creates ambiguity on what is an appropriate price and this fuels concerns and perceptions of overpayment, contributing to managers also communicating with analysts about an acquisition (Perry & Herd, 2004). Still, acquisition premiums are vulnerable to bias associated with anchoring the price paid for a target firm using comparable deals (Beckman & Haunschild, 2002; Malhotra et al., 2015) or its 52-week high stock price (Berman, 2009).

Shareholders are also affected by the choice of payment method. Stock is a common form of payment for an acquisition; however, stock payment dilutes ownership of acquiring firm shareholders (Blackburn, Dark, & Hanson, 1997). While there are expectations that market reactions to an acquirer’s share price on the announcement of an acquisition predict acquisition outcomes (Secher & Horley, 2018), market reactions to acquisitions using stock as payment may be more about ownership dilution (Andrade, Mitchell, & Stafford, 2001; Blackburn et al., 1997). Another important aspect is that not all shareholders are alike. For example, family owned firms might pursue objectives beyond pure value maximization (Feldman, Amit, & Villalonga, 2016), such as the socioemotional wealth (Gomez-Mejia, Patel, & Zellweger, 2018) or risk reduction through diversification (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Lester, 2010). Additionally, institutional investors can hold shares in both an acquiring and target firm, and they may be motivated to vote for an acquisition based on gains from owning target firm shares (Bethel, Hu, & Wang, 2009).

M&A research largely relies on U.S. or at least public firms (Meglio & Risberg, 2010; Zollo & Singh, 2004), but family firms also use M&A to respond to environmental changes and sustain their business (Steen & Welch, 2006). Still, family values affect strategic decisions and business behaviors of family businesses and their focus on issues, such as management succession, can vary from non-family firms (Steier, Chrisman, & Chua, 2004). Even though M&A involve family firms have a lower value and volume (Miller et al., 2010), the global annual transaction volume and the high number of family firms indicate that the involvement of family businesses in M&A – either as an acquirer or as a target – is highly relevant (Mickelson & Worley, 2003). Further, family influence and ownership is not limited to small firms (Anderson, Mansi, & Reeb, 2003) and they play an important role in Europe. While continuous change, in our case through M&A, is essential for family firm survival, they confront a trade-off between change and continuity (Kotlar & Chrisman, 2018). Consequently, different combinations of firms (e.g. family and non-family firms) involved in M&A imply that not all deals are alike (Bower, 2001). In other words, family firms are shaped by a unique context that affects their strategic priorities, governance structures, social responsibility and learning behavior (Chrisman, Fang, Kotlar, & De Massis, 2015; Miller et al., 2010). Family firms can display different behaviors in comparison to their non-family counterparts (Schulze & Gedajlovic, 2010), and we hold that this also leads to distinctive behaviors and consequences when it comes to M&A.

Employees

Acquisitions significantly influence the psychological contracts of how employees view their employment (Bellou, 2006). While employees expect change following and acquisition (Risberg, 1997), acquisitions are disruptive and they create uncertainty (Rafferty & Restubog, 2010) involving possible job loss, increased workload, and changes in organizational structure (Ullrich & Van Dick, 2007). Without considering the implications of change associated with an acquisition, employee uncertainty can turn into resistance (Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999). However, awareness of employee concerns during acquisitions (Seo & Hill, 2005) can mitigate conflict and employee resistance (Ellis, Weber, Raveh, & Tarba, 2012) by demonstrating a commitment to employees and establishing mutual understanding (Bauer et al., 2018; Birkinshaw et al., 2000).

Taking steps to address employee concerns by communicating how an acquisition influences them (King & Taylor, 2012; Secher & Horley, 2018), can lower the risk of unplanned turnover from employees simply leaving. For example, key employees often get job offers within a week of an acquisition announcement (Brown, Clancy, & Scholer, 2003). As a result, communication is needed to reduce employee uncertainty and increase commitment to change (Rafferty & Restubog, 2010; Secher & Horley, 2018). Further, M&A success depends on the people responsible for making expected improvements, or the employees of a combined firm.

However, even intentions to communicate openly may be difficult to execute. Confidentiality agreements used prior to acquisition announcement and completion, to avoid disclosure and comply with regulatory oversight, restricts an exchange of communication and can create hard feelings for employees that were not informed (Harwood & Ashleigh, 2005). One important signal in the shift to be more open can come in the form of a letter from the CEO to all employs when an agreement is finalized (Schweiger & Denisi, 1991). This can also avoid employees from learning about an acquisition from media coverage. The combined implication contributes to an inverted-U relationship in communication needed between combining firms (Allatta & Singh, 2011), or the demands of communication rapidly increase before declining.

A separate consideration is whether employees belong to a union, and more experienced acquirers get unions to agree to goals and milestones (Meyer, 2008). One reason is that union employees are more likely to have lower satisfaction in response to acquisition announcements (Covin, Sightler, Kolenko, & Tudor, 1996). Another reason is that union representatives can serve as key boundary spanners across organizations and collaboration with union and management can enable change following an acquisition (Colman & Rouzies, 2018).

Competitors

Other firms offering similar products or services in the same market generally oppose an acquisition, as M&A offer a means of avoiding or reducing competitive threats (Porter, 1980). More nuanced views emphasize potentially shared interests and opportunities for cooperation (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996), but competitors still pose a threat to an acquirer reaching M&A goals. As discussed earlier, competitors can take advantage of uncertainty from an acquisition to recruit talent. However, competitors can also take other actions to reduce the benefits from making an acquisition, including lowering prices and stealing customers (King & Schriber, 2016). These competitive attacks are often launched during integration (Clougherty & Duso, 2011), or acquiring firm managers typically have an internal focus and are vulnerable to competitor retaliation (Cording, Christmann, & King, 2008; King & Schriber, 2016). For example, research identifies the best time to attack a competitor is when they are distracted by an acquisition (Meyer, 2008). An acquisition also changes the dynamics within an industry and rivals can benefit from an acquisition through increased market power. However, associated share price changes are also associated with rival firms also becoming acquisition targets (Song & Walkling, 2000). For example, grocery firms lost a combined $40 billion in market capitalization when Amazon announced its acquisition of Whole Foods (Domm & Francolla, 2017). As a result, competitors can also respond to an acquisition by making an acquisition of their own (Keil et al., 2013) possibly at lower prices. However, later acquisitions generally involve less attractive targets.

Customers

Another issue is that disruption and uncertainty from an acquisition is not isolated to a firm’s employees. Business relations are often dynamic and substantial change, such as M&A, can lead to changes in relations to and loss of customers (Anderson, Havila, & Salmi, 2001), typically because customers perceive loss of attention (Öberg, 2014). Earlier we discussed that competitors will try and poach customers, but customers also act to reduce dependence on suppliers that combine (Rogan & Greve, 2014) and two-thirds of firms lose market share following an acquisition (Harding & Rouse, 2007).

Communicating the impacts of an acquisition to customers can limit problems that can eliminate the value from making an acquisition (King & Taylor, 2012). For example, IBM halved its contracts with two combining suppliers because no one in the firms communicated what the acquisition meant to their primary customer (Marks & Mirvis, 2010). Meanwhile, for consumer businesses, it may be important to maintain a target firm’s brand to avoid customer loss (Secher & Horley, 2018).

Advisors

An industry of people depends on facilitating acquisitions for their livelihood, and completing an acquisition depends on external advisors (Kesner et al., 1994). A consistent admonition is to hire the best advisors as they can complete deals faster and help uncover issues with an acquisition (Angwin, 2001; Anslinger & Copeland, 1996; Hunter & Jagtiani, 2003) to help firms avoid bad decisions (Kim et al., 2011). For example, Lockheed Martin canceled a planned acquisition after external auditors found improper international payments by a target firm that also led to a government investigation (Marks & Mirvis, 2010). Additionally, advisors can augment staffing needs that peak during acquisition integration. For example, using human resource consultants during an acquisition can have positive effects (Correia, e Cunha, & Scholten, 2013). This underscores that there are different types of advisors including, investment bankers, legal counsel, accounting and management consultants (Secher & Horley, 2018). There is also a need for advisors with experience in a target country for cross-border acquisitions (Westbrock, Muehlfeld, & Weitzel, 2017).

While advisors can offer important insights and managerial resources during several acquisition phases, an overriding consideration involves the need to use objective advisors (Lovallo et al., 2007), as advisors may be motivated to complete a deal or display conflicts of interest (Secher & Horley, 2018). For example, bankers may have conflicts of interest if they have non-public information about a target firm’s financial issues and an acquisition means associated debts have a lower risk of being repaid (Allen, Jagtiani, Peristiani, & Saunders, 2004). Moreover, investment bankers are often paid in relation to the acquisition value rather than its performance, implying they benefit from suggesting also less than optimal M&A (Parvinen & Tikkanen, 2007) at high prices.

Government

Evidence of the potential of M&A to change industries and impact customers is visible in governments issuing laws regulation to shape the institutional environment for M&A. Antitrust regulation or laws providing consumer protection against monopolies exist in 90 countries that require public review of acquisitions (Dikova, Sahib, & Van Witteloostujin, 2010). The Sherman Act of 1890 aimed to protect competition, and the first antitrust action in the U.S. took place in 1904 (Banerjee & Eckard, 1998). Announcements of government reviews of an acquisition are associated with a negative market reaction and forced divestment of units can lower combined firm performance (Ellert, 1976), as U.S. regulators demand changes in the majority of deals reviewed (Monga, 2013). Still, government influence comes in additional forms. For example, China takes an active role in domestic and cross-border acquisitions (JP Morgan, 2018). However, the U.S. government also influences merger activity by encouraging consolidation of the defense industry (Augustine, 1997) and pressuring Bank of America to acquire Merrill Lynch following the 2008 financial crisis (Story & Becker, 2009).

Additionally, some countries hold “golden shares” in firms. For example, the United Kingdom holds “golden shares” in British Aerospace and Rolls Royce that limits acquisitions (Economist, 2018), and Brazil holds a “golden share” in Embraer complicating a proposed takeover by Boeing (Fortune, 2017). Additionally, the Chinese government takes an active role in acquisitions through government ownership (Chen & Young, 2010). Teva also waited five years to acquire Hungarian firm Biogal based on government acceptance of lay-offs (Brueller et al., 2016). The proceeding examples are consistent with acquisitions increasingly involve cross-border considerations, so there is a need to consider multiple governments and not just an acquirer’s home country (King & Taylor, 2012). As a consequence, there is evidence that firms attempt to influence regulation. For example, Hol-burn & Vanden Bergh (2014) find firms increase political donations prior to announcing acquisitions in regulated industries. Additionally, AT&T publicly lobbied the government in support of its merger with Time Warner (Breland, 2017; Bukhari, 2017; Kang & Lipton, 2016).

Stakeholders and managerial risk

While acquisitions are known to increase turnover for target executives (Krug, 2003; Krug, Wright, & Kroll, 2014), both acquiring and target firm executives can experience higher turnover. For example, acquiring firm CEO turnover is higher after an announced acquisition is canceled (Chakrabarti & Mitchell, 2016) and for CEO that make acquisitions (Haleblian & Finkelstein, 1999; Lehn & Zhao, 2006). Further, the risk of dismissal for an acquiring firm CEO increases if they completed more than one poorly performing acquisition (Offenberg, 2009). This suggests top managers in acquiring firms face real risks when they fail to consider stakeholders of an acquisition. Further, an identified “red flag” for acquisitions involves circumstances where only the CEO believes in the deal (Lovallo et al., 2007). This can have heightened importance, as research suggests CEO traits may make them more likely to complete acquisitions (Gamache, McNamara, Mannor, & Johnson, 2015), and it further underscores the need for acquiring firm managers to consider stakeholders impacted by an acquisition.

Communication

In light of the various stakeholders affected by and affecting M&A, managers need to facilitate communication with different stakeholder groups. One explanation for General Electric’s success with acquisitions is developing a communication plan across multiple phases of integration (Ashkenas & Francis, 2000). Typically, M&A are generally planned in closed circles involving mainly top managers, though research emphasizes the need to inform employees (Schweiger & Denisi, 1991).

Implementing change in an uncertain context is associated with a tendency to focus inward following an acquisition (Cording et al., 2008; Lambkin & Muzellec, 2010), but this can overlook the need for a communication plan that considers multiple stakeholders (Lambkin & Muzellec, 2010; Sillince, Jarzabkowski, & Shaw, 2012). It is also necessary to consider different perspectives, as multiple interpretations of dialogue are more likely in cross-border acquisitions (Risberg, 2001). While there is an assumption that communication helps and this drives a need for greater communication in the process of change (Rafferty & Restubog, 2010; Rousseau, 2001; Sinetar, 1981), organizations can experience greater success using ambiguous communication to enable multiple interpretations and greater flexibility (Eisenberg, 1984; Gioia, Nag, & Corley, 2012). For example, managers may use uncertainty to increase their power relative to other stakeholders (Hill & Jones, 1992). However, ambiguous communication can be counterproductive for international acquisitions where cultural differences can contribute to misunderstanding (Risberg, 2001).

For acquisitions, this reflects the need for communication to facilitate trust and manage a dichotomy where there is a need to both hold back and share information with employees (Harwood & Ashleigh, 2005) and other stakeholder groups. For example, there are concerns that competitors can benefit from acquirers communicating too much about an acquisition and its integration (King & Schriber, 2016). Still, effective change communication tends to reveal rather than conceal (DiFonzo & Bordia, 1998). Meanwhile, the amount of communication is also associated with the speed of integration with faster integration associated with less communication (Saorín-Iborra, 2008), but this may be restricted to circumstances of limited change. Still, the pace and extent of change is examined less frequently in research on organizational change (Amis, Slack, & Hinings, 2004) and M&A research (Bauer, King, & Matzler, 2016).

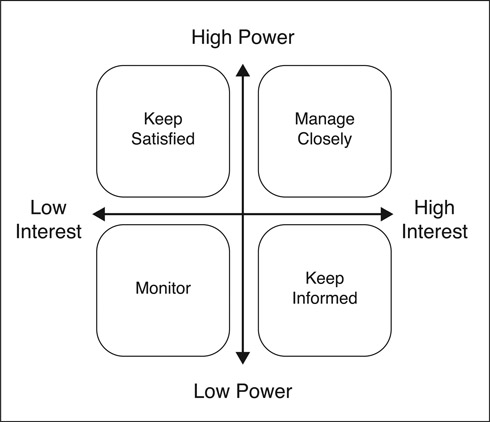

Figure 3.2 Classification of stakeholders based on power and interest

In considering stakeholders and communication, it may be helpful to classify stakeholders on dimensions of their power, legitimacy, and urgency (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, 1997). However, managers likely apply a simpler model that classifies stakeholders on power and interest and this provides advice on appropriate actions (Eden & Ackermann, 1998), see Figure 3.1. Graphing different stakeholders can also help avoid considering stakeholders in isolation, because responding to the concerns of one stakeholder can be countered by another stakeholder’s reaction. Success requires identifying an approach that balances or captures a majority of stakeholder concerns. In other words, failing to gain enough support from stakeholders will compel managers to make changes (Hill & Jones, 1992).

In assessing stakeholders, managers need to identify powerful stake-holders, or those where gaining support is most needed. As part of identifying important stakeholders, consider “deal breakers” for an important stakeholder, or what issues are “hot topics” or serve as conditions for their support. This can explain a focus on shareholders in M&A research at the same time that it limits broader stakeholder interests. For example, it is important not to overlook any group of stakeholders or to simply provide a generic response based on their power and interest. Assessing stakeholders involves a continuous process as interests and power can change over time. For example, one stakeholder group may react to how another stakeholder group is treated.

Summary and outlook

M&A do not take place in a vacuum, nor are they fully controlled by those initiating the deal. Initial research considering stakeholders beyond shareholders, as research has only begun considered other interested parties, including employees, competitors, and customers. While there is growing research into the relations between M&A and stakeholders, different groups are generally considered separately. We argue that structured attention to stakeholders enhances an understanding of dynamic conditions surrounding M&A, and that communication is central to how M&A can be successfully managed. In other words, a clear understanding of involved parties can provide a needed foundation for approaching M&A. However, research needs to reflect that the order of events is central to how M&A evolve. This has been considered in research focusing on in timing of events and the pace of change. Therefore, we next turn to a process perspective of M&A and associated research variables.