Assessing information culture

Abstract:

This chapter focuses on the concept of information culture and how to apply this idea to your own organisation in order to identify particular problem areas and to work out appropriate solutions. A three-level framework for assessment is outlined, and the characteristics of each level are described. Suggestions are provided in order to use this tool in an organisation to diagnose its information culture.

Introduction

Back at the start of this book I introduced the concept of information culture. Every organisation, no matter how large or small it is, regardless of its type and function, wherever in the world it is situated, has an information culture. Understanding the organisational culture is critical in working out which features characterise the organisation’s information culture. This chapter considers how to tease out exactly those characteristics which will define the organisation’s information culture. The chapter begins by outlining an overall framework to use for assessment, then describes each level of this framework, suggesting how to go about collecting the data necessary to compile a holistic picture of information culture. Armed with this information, you will then be able to identify and prioritise areas for action.

Framework for assessment

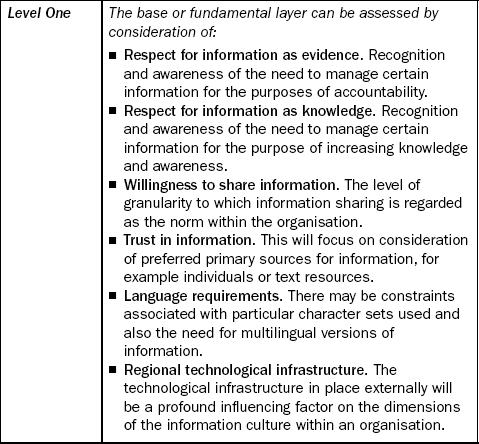

In the same way that we have established that organisational culture consists of multiple layers, information culture is shaped by influences occurring at different levels – some of which are more open to change than others! So I have developed a framework for assessment, which takes this into account. The framework is shown in the following table:

Each of these levels is discussed in the following sections, together with suggestions as to how to gather data for assessment.

Level one

This level is the base or fundamental layer of an organisation’s information culture. It would be very difficult, if not impossible, to effect any change at this level, but understanding of its dimensions is critical in order to make sure that the information strategies you do develop are appropriate for the organisation and will be adopted. This level has the largest number of features that need to be taken into consideration, beginning with respect for information managed for the two key purposes that will be the focus of records managers, archivists and librarians. The remaining characteristics at this level are all linked to the location of the organisation, whether they are associated with national culture (willingness to share information, trust in information) or structural features (language, technological capabilities).

Respect for information as evidence. The extent to which it is accepted within the organisation that certain information needs to be managed for the purposes of accountability provides the measure by which you can ascertain the degree of respect for information as evidence. This can be assessed by answering the following questions:

![]() Is there an organisation-wide filing system for current records?

Is there an organisation-wide filing system for current records?

![]() Are there professional staff employed to undertake records management?

Are there professional staff employed to undertake records management?

![]() If an organisation-wide filing system exists, does it encompass all records, regardless of format and media?

If an organisation-wide filing system exists, does it encompass all records, regardless of format and media?

![]() Does management consider that recordkeeping should be part of everyone’s roles?

Does management consider that recordkeeping should be part of everyone’s roles?

![]() Do employees throughout the organisation consider recordkeeping to be part of their responsibilities?

Do employees throughout the organisation consider recordkeeping to be part of their responsibilities?

![]() Are systems and procedures in place to ensure that records are retained only as long as necessary?

Are systems and procedures in place to ensure that records are retained only as long as necessary?

![]() Is the organisation aware of requirements to identify, protect and preserve records of archival value?

Is the organisation aware of requirements to identify, protect and preserve records of archival value?

![]() Are there policies and procedures in place to archive records, either in-house or by transferring to a designated archival repository?

Are there policies and procedures in place to archive records, either in-house or by transferring to a designated archival repository?

Some of these questions can be answered simply by observation and identifying relevant policies. Others will need more work, in particular the question relating to employees’ attitudes towards recordkeeping. In this case, it will be important to collect data from staff, either by interview, focus group or by constructing a questionnaire.

If all these questions can be answered with an emphatic and unambiguous ‘yes’, then the organisation shows a high respect for information as evidence. The more negative the responses, the lower the respect that is accorded to managing information for accountability purposes.

If there is very little existing activity relating to the management of current and archival records, then this does not mean of course that the relevant infrastructure cannot be introduced. But you will need to be aware that the need to promote and justify records management will be an ongoing concern; it should never be assumed that records management will be routinely recognised as being a good thing. This is particularly the case where employees in the organisation do not recognise the need to take responsibility for recordkeeping as part of their workflow.

Respect for information as knowledge. The extent to which it is accepted within the organisation that certain information needs to be managed for the purpose of increasing knowledge and awareness provides the measure by which you can ascertain the degree of respect for information as knowledge. This can be assessed by answering the following questions:

![]() Are library services used by employees to inform their work?

Are library services used by employees to inform their work?

![]() Are there professional staff employed to manage information for knowledge and awareness?

Are there professional staff employed to manage information for knowledge and awareness?

![]() If professional librarians are employed, does the scope of their responsibilities extend beyond a physical library?

If professional librarians are employed, does the scope of their responsibilities extend beyond a physical library?

![]() If a library exists, does it have sufficient funding to buy necessary information resources?

If a library exists, does it have sufficient funding to buy necessary information resources?

![]() If a library exists, does it have sufficient space to house resources?

If a library exists, does it have sufficient space to house resources?

![]() Are employees encouraged to ensure that their work is informed by consulting a variety of information resources?

Are employees encouraged to ensure that their work is informed by consulting a variety of information resources?

![]() Do employees routinely go beyond Google when searching for information?

Do employees routinely go beyond Google when searching for information?

If all these questions can be answered ‘yes’, then the organisation shows a high respect for information as knowledge. The greater the number of negative responses, the lower the respect that is accorded to managing information for the purposes of increasing knowledge and awareness. In those cases it could be important for professional information managers to demonstrate expertise by getting involved in any other information projects within the organisation that are underway, such as intranet development. Here, professional skills can be applied to organising and structuring information, and linking to relevant external resources. It becomes important to show that information management is not something that is simply a feature of what may be thought of by staff as a very narrow and perhaps outmoded entity, a library, but is applicable in ways that can meaningfully support the organisation’s activities.

Willingness to share information. The level of granularity to which information sharing is regarded as the norm within the organisation is the third characteristic to assess at this fundamental level of our information culture framework. Here, you should attempt to find out whether or not people are likely to be inclined to share information with their colleagues, and whether those colleagues will be limited to only those working in the same team or whether they will include those working in other departments.

The deciding factor here is likely to be related to national cultural characteristics. The tables provided in Chapter 2 relating to Hofstede’s dimensions indicate that a view of sharing information as an attribute of organisational success versus a view of withholding information as an attribute of organisational success are characteristics relating to the individualist/collectivist dimension. In addition, the characteristic of openness with information is associated with countries that ranked low on the power distance dimension, whereas high power distance is associated with information constrained by hierarchy. The key questions to be asked therefore are:

![]() Where is the organisation situated?

Where is the organisation situated?

![]() What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the individualist/collectivist dimension?

What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the individualist/collectivist dimension?

![]() What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the power distance dimension?

What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the power distance dimension?

Dimension rankings can easily be ascertained by using the online tool available at Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions Resources http://www.geert-hofstede.com/geert_hofstede_resources.shtml.

If your research reveals that either the whole or part of the organisation and its employees are based in a country which scores highly on the collectivist dimension and/or the power distance dimension, then be prepared to factor a reluctance to share information widely into the overall design of your information management system. A high score on the collectivist dimension, though, will probably indicate readiness to share information with colleagues in the same team, but a resistance to sharing with those outside this workgroup.

Another factor that will influence willingness to share information, which is not related to national cultural characteristics, relates to the function and purpose of the organisation, and the sector that it is operating in. Security requirements and competitiveness will both be factors that will inhibit willingness to share information with colleagues. So further questions could be:

![]() Are security classifications applied to routine operational activities?

Are security classifications applied to routine operational activities?

![]() Do employee reward systems encourage individual rather than team approaches to activities?

Do employee reward systems encourage individual rather than team approaches to activities?

An affirmative answer to either of these questions will certainly indicate that sharing information with colleagues is not likely to be encouraged, or even be the right thing to do. If there are security reasons why information should be restricted rather than shared then it is imperative that information management systems support these considerations. If reward systems promote hoarding rather than sharing information, then it would be worth checking to see that this is deliberate rather than an inadvertent consequence. For instance, if there are any aspirations voiced as to becoming a learning organisation, then it would be good to point out the inhibitory effect of the performance management systems that are in place. This feature is unique in terms of level one characteristics, as it could be easily influenced or changed if desired by the organisation.

Trust in information. This is the first of two factors in the assessment framework relating to trust, the other being at level three. At level one, this factor considers which are likely to be the most trusted primary sources for information, for example, individuals or text resources. The degree of trust will be evidenced by preference, i.e. which sources of information are preferred. Again, national cultural characteristics are likely to be significant. The tables in Chapter 2 indicate that two characteristics associated with differences on the individualist/ collectivist dimension are relevant here. The first characteristic relates to preferences for high context rather than low context information. This influences whether communication takes place based primarily on the context of the information, or on the explicit content. So if the preference is high context, images may communicate information adequately. If the preference is for low context, then words will definitely be needed. The second characteristic relates to preferences for relying more on one’s social network as a source of information rather than relying on published sources.

So, the key questions to assess which information will be trusted and therefore used are:

![]() Where is the organisation situated?

Where is the organisation situated?

![]() What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the individualist/collectivist dimension?

What ranking does this/these place(s) have on the individualist/collectivist dimension?

Dimension rankings can easily be ascertained by using the online tool available at Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions Resources http://www.geert-hofstede.com/geert_hofstede_resources.shtml.

If the organisation and the majority of its employees are based in locations which score highly on the collectivist end of this dimension, there are likely to be preferences for nontextual information and perhaps less use of published (whether online or in traditional print format) resources for initial fact finding. However, I do not think that this factor can be solely interpreted based on analysis of a single cultural dimension. Further investigation as to the extent to which people are willing to trust their colleagues as opposed to rely on official written sources could be carried out. In this case, survey questions could be developed to find out employee preferences. For instance,

![]() If you need to find out what the requirements are to protect personal information in this organisation, what would be your first course of action:

If you need to find out what the requirements are to protect personal information in this organisation, what would be your first course of action:

Consistent preferences for written sources such as the policy documents will indicate a high trust in textual information. Preferences for asking people will certainly emphasise the importance of training, and making sure that individuals are aware and up-to-date with the content of policy.

Language requirements. The languages that the organisation uses and needs to communicate with are fundamental features of its information culture and should be obvious. There may be constraints associated with particular character sets used and also the need for multilingual versions of information. This is a very straightforward factor to assess, but omitting to take this into consideration may result in unforeseen consequences when managing digital information. Key questions are:

![]() Is there a need to publish/disseminate/use information in more than one language?

Is there a need to publish/disseminate/use information in more than one language?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then make sure this is kept in mind when considering any strategies for the rendering of digital documents.

Regional technological infrastructure. This is the last of the level one characteristics and is a very practical feature that must be taken into account. It is particularly important, for instance, when considering guidance and advice developed in another region, which may quite simply be not applicable given local constraints. The technological infrastructure in place externally will be a profound influencing factor on the dimensions of the information culture within an organisation. It will affect which tools are used to manage information, the ways in which employees work, including the extent to which they are constrained by the physical boundary of the organisation. Determining the capabilities of the technological infrastructure which supports organisational systems will be relatively straightforward, as this information should be available from published resources. The Economist Intelligence Unit, for example, provides an annual ranking of e-readiness for over sixty countries (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2009).

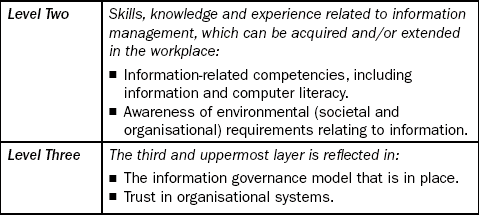

Level two

The second level of the information culture assessment framework addresses employees’ skills, knowledge and experience related to information management, which can be acquired and/or extended in the workplace. This should be the level that you target most attention to as this is where you can really make a big difference! The two categories to focus on are:

![]() Information-related competencies, including information and computer literacy. Do staff know how to evaluate the authority of information resources? Are staff aware of the need to assign appropriate metadata to documents they create? Are staff aware of the risks involved in using USB keys for data storage? And so on.

Information-related competencies, including information and computer literacy. Do staff know how to evaluate the authority of information resources? Are staff aware of the need to assign appropriate metadata to documents they create? Are staff aware of the risks involved in using USB keys for data storage? And so on.

![]() Awareness of environmental (societal and organisational) requirements relating to information. Are staff aware of the legislative requirements to manage information in certain ways, for example to protect personal information? Are staff familiar with the requirements of relevant organisational policy?

Awareness of environmental (societal and organisational) requirements relating to information. Are staff aware of the legislative requirements to manage information in certain ways, for example to protect personal information? Are staff familiar with the requirements of relevant organisational policy?

Sometimes the focus of any training delivered by information management staff is solely on this last factor, the policy that has been developed in-house. This is not at all surprising as probably the information management team has spent many hours in crafting the required policy, developing associated procedures, and getting management approval for the whole package. But concentrating solely on raising awareness of, say, organisational records management requirements, will guarantee only partial success in accomplishing your overall goals of promoting effective information management. This is because staff simply may not have the contextual awareness necessary to understand why the policy is in place, and/or the skills necessary in order to conform to the policy. If either of these components is missing, then training objectives will not be realised.

The information that you have gathered to provide your level one assessment will probably have given you some insight into your organisation’s employees’ information-related competencies, and perhaps their awareness of information management requirements as well. So you may already have a good idea of which areas need to be addressed by training. However, particularly if you are responsible for information management in a large and dispersed organisation, more rigorous identification of training needs may need to be carried out. Requirements for information and computer literacy will vary according to individual responsibilities and the systems that are in use. Particular issues may range from information retrieval to managing information overload, as well as proficiency in using specific software packages. Target each level of your organisation, and try to get an overview of information management related training needs by asking staff about problems they experience in working with information. The method you use to ask staff will depend on the size and complexity of your organisation, and the information tools already available. So you may consider developing a short online survey for staff to complete, or perhaps just wander around and chat to some key people.

Determining awareness of societal and organisational requirements for managing information will be a straightforward process. The first step will be to identify all external requirements relating to information management, and then to see whether relevant organisational policies exist. The next stage will be to analyse the extent to which the content of the policy reflects the intent of the external requirement. (At this stage of course there may be remedial work required to upgrade the policy so that it does accurately reflect any external requirements.) The final step will be to find out whether individuals are aware of appropriate policies. This can be done by asking staff, or if policies are online it may be possible to view data relating to their usage. Although in this case, beware of the level one ‘trust in information’ characteristic which may skew your findings.

Assessment of people’s knowledge and understanding of requirements to manage information, in conjunction with your observations and any information gathered for the analysis at level one, will provide you with a solid basis to identify learning objectives for your training programme. Once the learning objectives are clearly formulated the content will emerge. For example, if you have found out that staff are unaware of the reasons why a shared document repository should be used to save their work, then a learning objective could be ‘Ensure staff are familiar with options for saving documents’. Content can then be developed which will emphasise the advantages and/or disadvantages of each option.

Almost as important as identifying training needs is deciding how the training should be delivered. Options are many and varied – here are a few of the decisions that will need to be made. Should training be delivered on an individual or group basis? If group, how should the groups be made up – by functional area or representing a range of different functions? Should groups be segregated by level of employee, or should they be cross-sectional in terms of organisational hierarchy? Will face to face contact be needed, or should online resources be developed? What types of supporting materials should be developed? Should external trainers be used, or will existing information management staff be sufficient?

It is important that your decision making here is based on the findings from your level one analysis. In other words, cultural characteristics play a critical role, in particular rankings on the power distance and individualist/collectivist dimensions.

If the employees of an organisation were raised and work in a country with a ranking at the collectivist end of the individualist/collectivist dimension (for example, China and South East Asian countries), then training is more likely to be effective if it is delivered on a group basis. The composition of the groups should reflect work units rather than be assembled from across the organisation. Also there is likely to be a preference for high context communication. This suggests that diagrams and images will be very effective as a means of communicating relevant training messages, and that these should be used in any supporting resources that are developed.

In contrast, for those employees who grew up and are working in a country with an extreme individualist ranking (Australia and the United States, for example), training focused at the individual level is more likely to be effective. In these countries the preference is likely to be for low context communication, so consideration should be given to providing explicit text-based resources for use as supporting references.

Rankings on the power distance dimension will influence whether training should be delivered to a cross-section of the organisational hierarchy or not. If the setting is one where there is a high score on the power distance dimension, i.e. status is accorded a high importance, then trying to deliver training to a group of participants representing all ranks will probably be doomed to failure. Those at the lower end would certainly not want to risk offending the boss and so would maintain a very low profile. Managers, on the other hand, would be wary of losing face and so would likely to be equally reluctant to fully participate. In this case it would also be wise to consider using a source of expertise for training which would be considered neutral – that is, not aligned to one particular organisational group.

The final decisions on these points and eventual design of your training programme will, of course, be constrained by the resources you have available (what funding is available, whether information management staff have the necessary expertise to develop and deliver training, and so on). But establishing first of all what likely cultural preferences there are will provide you with a firm foundation for a successful training programme to address the features represented at level two of the information culture framework. The final point to remember is that training should not be regarded as a one-off activity. Follow-up training needs should be considered, and new staff coming into the organisation should be identified and trained as soon as possible.

Level three

The uppermost level of the framework provides further data for the assessment of the information culture. The two features to be considered here are information governance and trust in organisational information systems.

Information governance. The information governance model that is in place will be reflected in the degree of coherence of the overall information architecture. A typology of information states developed by Thomas Davenport and colleagues (Davenport et al., 1992) provides an easy to apply template based on features that are very familiar to most of us. These authors identified five distinct models, which they depict as political states:

![]() Information federalism. This approach to information management is based on negotiation and consensus on the organisation’s key information elements and reporting structures.

Information federalism. This approach to information management is based on negotiation and consensus on the organisation’s key information elements and reporting structures.

![]() Information feudalism. Here, individual business units manage their own information, define their own needs and report only limited information to the overall organisation.

Information feudalism. Here, individual business units manage their own information, define their own needs and report only limited information to the overall organisation.

![]() Information monarchy. In a monarchy, information categories and reporting structures are defined by the leaders of the organisation, who may or may not share information after collecting it.

Information monarchy. In a monarchy, information categories and reporting structures are defined by the leaders of the organisation, who may or may not share information after collecting it.

![]() Information anarchy. As the name suggests, there is an absence of any overall information management policy, and individuals obtain and manage their own information.

Information anarchy. As the name suggests, there is an absence of any overall information management policy, and individuals obtain and manage their own information.

![]() Technocratic utopia. This approach to information management is characterised by an emphasis on information engineering and technological solutions, particularly focusing on new and emerging technologies. (Davenport et al., 1992: 56)

Technocratic utopia. This approach to information management is characterised by an emphasis on information engineering and technological solutions, particularly focusing on new and emerging technologies. (Davenport et al., 1992: 56)

In my experience, where information anarchy is the norm and this has been recognised as a problem, the solution that is proposed is often the technocratic utopia, the magic bullet which will bring everything under control. The reality, of course, will be quite different; if all information management problems could be addressed by the implementation of a technological system then our professional skills and expertise would not be needed. Which is most definitely not the case!

In order to determine which model typifies your organisation, try to find out the extent to which information systems interconnect. So the key questions will be:

![]() What functions does the organisation carry out?

What functions does the organisation carry out?

![]() What information systems support those functions?

What information systems support those functions?

![]() Do the information systems use data that is common to all systems?

Do the information systems use data that is common to all systems?

![]() Are single or multiple log-ons required to access these systems by individuals who need to use their information to carry out their work?

Are single or multiple log-ons required to access these systems by individuals who need to use their information to carry out their work?

If you find that there is a pattern of multiple systems that do not interconnect, then beware of attempts to develop a new system to fix isolated problem areas. Find out what plans there are to address this area, and marshal your arguments against the deceptive lure of a technological utopia!

Trust in organisational systems. The final area that must be assessed in order to understand your organisation’s information culture is to find out the extent to which employees trust existing in-house information management systems. This is critical – no matter how robust your systems are, if employees do not trust those systems, those employees will not use them. The result being, of course, that a large proportion of your efforts to establish comprehensive and effective information management efforts will have been in vain.

The consequences of lack of trust were vividly demonstrated to me when I carried out the case study of the Australian university. This university had a records management unit, which had been in existence for fourteen years. It was well resourced, in that it had five members of staff, all with professional qualifications in either records or archives. A filing system and retention schedule had been devised, and the scope of the records unit was enterprise wide, i.e. not limited to one department or function. So in terms of the framework level one factor, respect for information as evidence, there were plenty of signs to suggest that information as evidence was respected and valued by the organisation.

However, when I interviewed staff outside the records unit, I found that there was a marked tendency for people to keep their own files rather than add them to the central system. One manager described the situation in her area as an ongoing battle to get anyone to add records to the central filing system. The reason for this was a perception that files were destroyed before they should have been. Whether this was fact or fiction was immaterial, the point being that the filing system was perceived as being a place that could not be trusted to store the records needed for as long as they were required for operational purposes. It did not appear that this was a feature that could be addressed by modification of the retention and disposal schedule, which should provide the ultimate authority as to how long information needs to be kept. It was a case, quite simply, of lack of trust.

The lack of trust did indeed sabotage the effectiveness of the system. It was not just a question of not using files, but of withholding key documents. For instance, records relating to the negotiation and establishment of contracts and agreements might be filed, but the original signed copy of the agreement was kept ‘safely’ by the individual responsible for that area of work. This raises all sorts of problems relating to the proper storage and protection of the record, as the records unit had procedures in place to ensure appropriate security. A more disturbing aspect, though, is the risk that decisions would be made based on incomplete evidence. In the case of the contract, it would be relatively straightforward to spot the absence of the crucial record. But if the missing component was not so obvious, say in the case of a more unstructured correspondence file, then users of the file would be unaware that the information was incomplete.

Lack of trust can also be very detrimental to library operations. As with the records management system, signs of lack of trust in this setting can be witnessed as contributing factors to a desire to keep resources in the staff member’s own working area, rather than in a central library; they will also be manifest in a lack of engagement with library services, the unfortunately familiar scenario where departments start building their own collections rather than using the organisation’s library.

The key questions to be asked to gather data to assess the level of trust in organisational systems are quite straightforward:

![]() Are appropriate systems in place?

Are appropriate systems in place?

![]() Is information withheld from systems?

Is information withheld from systems?

![]() Are there any significant barriers to use, such as location of a physical repository in a location remote from users, or insufficient access to technological systems?

Are there any significant barriers to use, such as location of a physical repository in a location remote from users, or insufficient access to technological systems?

If the answer to the first two questions is yes, and no to the third, the most likely cause of the problem is lack of trust. Once this has been identified then an ongoing programme to modify perceptions will have to be developed. Establishing trust is not easy, it will take ongoing effort and there will be a need to work hard on relationship building as well as continually demonstrating responsiveness to user needs.

Conclusions

This chapter has explored the concept of information culture, and provided a framework to use in order to assess it. Unlike information audits or surveys, the emphasis is not on what information is created, available and used, but rather on the ways in which people behave, and inherent values and attitudes which will impact on the way that information is managed. The framework distinguishes between factors which can be changed, and those that cannot, but including both emphasises the requirement for solutions tailored to the organisation’s needs. The final chapter provides four different scenarios of information management projects to demonstrate how different strategies for implementation will have to be developed in order to take into account variation in organisational setting.

References

Davenport, T.H., Eccles, R.G., Prusak, L., Information politics. Sloan Management Review (Fall). 1992:53–65.

Economist Intelligence Unit from. The 2007 e-readiness rankings. 2009. http://www.eiu.com/site_info.asp?info_name=eiu_2007_e_readiness_rankings