The significance of organisational culture

Abstract:

This chapter explains the concept of organisational culture and establishes why it is necessary for information managers to understand this. The values accorded to information and attitudes to it are indicative of the information culture of organisations; understanding organisational culture will enable the development of appropriate strategies and systems. Two contrasting views of organisational culture are discussed, one which assumes culture is solely internally based and the other which acknowledges the external environment in which the organisation is situated.

Introduction

This chapter begins by discussing why it is important to understand organisational culture. Then I start to establish what organisational culture encompasses. Although it is a term that most people are familiar with, and many use frequently when discussing their workplace, interpretation and understanding vary greatly. Two of the key perspectives are discussed, one of which has unfortunately been very prevalent and influential on management thinking, to the detriment of information management. The final section of this chapter outlines the multilevel approach to organisational culture that underpins the thinking in this book, acknowledging the existence of national, occupational and corporate cultural influences in shaping our working environments.

Why is understanding organisational culture so important?

Whether you are a librarian, records manager or archivist, the objective of your work is to manage information. The primary purpose for which you are attempting to manage information will vary according to your occupation. Records managers and archivists manage information as evidence, for accountability. Librarians manage information for knowledge and awareness, and also sometimes for entertainment. So far, so good. These distinct purposes provide a universality for the work undertaken by information managers and enable us to work collaboratively (regionally, nationally and globally) to explore and develop appropriate technologies, systems and processes. However, the specific organisational context that librarians, records managers and archivists are working within is a primary influence on the way that they go about achieving their work objectives. For example, the way in which you would go about ensuring your clients are mindful of their information management obligations in a very structured setting such as a law firm would be quite different to a more anarchic environment such as a university.

Most information managers fulfil key roles in providing the necessary infrastructure to enable the organisation that they serve to function efficiently and effectively. But the nature of that organisation will vary widely, according to a number of factors, in particular

![]() Geography – Where the organisation is situated, whether it is multinational or restricted to one region or country. These features will determine the legislative environment, the languages used by employees and customers, and national cultural characteristics. Also of critical importance are the information and communication technology (ICT) capabilities of the location. For example, ready access to wireless internet facilities will be a significant influencer on the expectations of employees for accessing and creating information.

Geography – Where the organisation is situated, whether it is multinational or restricted to one region or country. These features will determine the legislative environment, the languages used by employees and customers, and national cultural characteristics. Also of critical importance are the information and communication technology (ICT) capabilities of the location. For example, ready access to wireless internet facilities will be a significant influencer on the expectations of employees for accessing and creating information.

![]() The functions of the organisation – These will determine the legislation and standards that the organisation is subject to, which in turn will influence the types of information created and required to be accessed and retained.

The functions of the organisation – These will determine the legislation and standards that the organisation is subject to, which in turn will influence the types of information created and required to be accessed and retained.

![]() The management of the organisation – This may affect the priority accorded to managing information, and resourcing of those activities. Also, the priorities accorded to information systems, information literacy and digital literacy skills of staff throughout the organisation will in turn impact on the success of information management initiatives.

The management of the organisation – This may affect the priority accorded to managing information, and resourcing of those activities. Also, the priorities accorded to information systems, information literacy and digital literacy skills of staff throughout the organisation will in turn impact on the success of information management initiatives.

These factors are intertwined, and are likely to influence each other, but all play a role in shaping the culture of the organisation. Each of these will be explored further in this book.

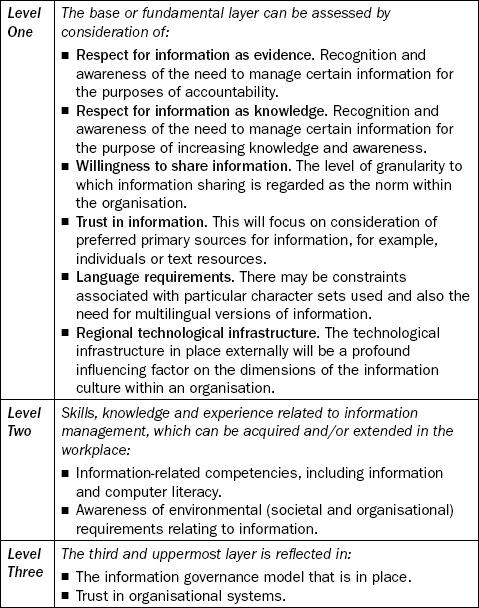

Understanding the importance of these factors will enable the diagnosis of an organisation’s information culture – that is, the values accorded to information, and attitudes towards it, specifically within organisational contexts. Every organisation, no matter how large or small, regardless of type and function, wherever in the world it is situated, has an information culture. Table 1.1 presents a framework for the assessment of information culture; the levels are explored in Chapter 6.

Information culture is inextricably intertwined with organisational culture, and it is only by understanding the organisation that progress can be made with information management initiatives.

Organisations are microcosms of their broader societal context. They may appear to be self-contained, but definitely do not exist in isolation from their broader context. Often consideration of organisational culture focuses solely on internal factors, primarily management and resourcing. The key aim of this book, however, is to highlight and untangle all those features that influence what happens at the library, records service or archives.

One of the features that characterise information management is the sheer diversity of settings in which it is implemented. For that reason, many practitioners remain in the same environment and it can be difficult to swap settings, largely because of the specialist skills and knowledge required. A law librarian, for instance, attempting to change focus to a hospital setting will often be regarded as making a career shift and may find entry into the new field problematic. Consequently, any consideration given to the more fine-grained or nuanced aspects of organisational culture is often overlooked. Where there is differentiation according to setting in literature and guidelines for practice, this is generally restricted to broad-brush domains such as medicine and law. Nevertheless, the work of information managers in, say, hospitals in various parts of the world, although focused on the same outcomes, may be quite different in terms of priorities accorded to different services and activities.

The ways in which information managers will be affected by organisational culture will vary according to the extent to which the main elements of their work (users and materials) are internal to the organisation, or external. For example:

![]() Special librarians in businesses, government departments, hospitals and so on will customise services to suit the needs of their clientele, who are likely to be generally internal to the organisation. Those needs will reflect, and be influenced by, the culture of the organisation.

Special librarians in businesses, government departments, hospitals and so on will customise services to suit the needs of their clientele, who are likely to be generally internal to the organisation. Those needs will reflect, and be influenced by, the culture of the organisation.

![]() Records managers and archivists in similar settings also have the challenge of customising and targeting services. In addition, the environment will greatly impact on the information itself that is the focus of their information management goals, namely, the ways in which records are created, managed and stored by individuals.

Records managers and archivists in similar settings also have the challenge of customising and targeting services. In addition, the environment will greatly impact on the information itself that is the focus of their information management goals, namely, the ways in which records are created, managed and stored by individuals.

![]() In public library settings, organisational cultural challenges will be experienced not so much from the user or information perspective, but in dealing with the parent body. Public librarians have to understand the organisational culture of the local authority in which they are operating, in order to formulate appropriate strategies and present them in such a way as to facilitate acceptance.

In public library settings, organisational cultural challenges will be experienced not so much from the user or information perspective, but in dealing with the parent body. Public librarians have to understand the organisational culture of the local authority in which they are operating, in order to formulate appropriate strategies and present them in such a way as to facilitate acceptance.

![]() In further educational settings such as universities, clients will vary much more widely on the spectrum of internal to external. Students occupy more ambiguous territory as they are officially part of the organisation, but may be quite peripheral, especially if study is on a part-time basis. Also the complexity of the subcultures associated with the different disciplines that make up the university is enormously challenging.

In further educational settings such as universities, clients will vary much more widely on the spectrum of internal to external. Students occupy more ambiguous territory as they are officially part of the organisation, but may be quite peripheral, especially if study is on a part-time basis. Also the complexity of the subcultures associated with the different disciplines that make up the university is enormously challenging.

Organisational culture and information management – academic research

There is an extensive body of literature published about research into information technologies and culture, including organisational and national comparative studies. The growth of multinational organisations, and deployment of information and communication technologies facilitating the globalisation of business have brought cross-cultural management and communication issues to the fore. An analysis of articles published in the leading information systems journals over a nine-year period identified over three hundred articles relating to global information management, i.e. ‘the development, use and management of information systems in a global/international context’ (Gallupe & Tan, 1999: 1).

In contrast to information systems, there has been very little published research on the role of organisational and/ or national culture in the library and recordkeeping fields. J. Periam Danton proposed an outline curriculum for the study of comparative librarianship and suggested a methodology to investigate this area (Danton, 1973). More recently, library researchers have been encouraged to include cross-cultural comparisons, and useful areas for study have been identified as intellectual policy legislation, regulation of mass media, science policy, censorship and library services, rather than the ‘touristtype’ descriptive report which is commonly found in library and information studies journals (Buckland & Gathegi, 1991). Philip Calvert (2001) used Hofstede’s dimensions to assess whether attitudes to service quality in academic library users were influenced by national culture. He notes that despite its suitability for this kind of study, Hofstede’s work does not appear to have been used before in information and library studies research (Calvert, 2001). Carolyn McSwiney discusses Hofstede’s dimensions in terms of informationseeking behaviour, and makes recommendations for librarians working in a multicultural context (McSwiney, 2003). Jennifer Rowley includes a brief discussion of the need to take into account national differences when determining knowledge management strategy, and proposing technological solutions (Rowley, 2003), and library practitioners are encouraged to take corporate culture into account when assessing library services (see Budd, 1996 for instance).

There are anecdotal accounts of national differences in recordkeeping practice, in the same vein as the ‘tourist-type’ literature mentioned by Buckland and Gathegi (1991).

However, there has also been consideration of cultural interactions and influences at a more scholarly level. David Bearman contrasts approaches in the United States and Europe to the management of electronic records, which he attributes to different cultural contexts, and suggests connections between Hofstede’s dimensions and archival practice (Bearman, 1992). Eric Ketelaar has drawn attention to national differences in archival systems, strategies and methodologies and in doing so advocated a comparative archival science to explore these differences (Ketelaar, 1997b, 1999, 2001, 2005).

The Electronic Recordkeeping Research project of the University of Pittsburgh developed a model for developing functional requirements for electronic records based on warrant. Warrant is defined as the ‘mandate from law, professional best practices, and other social sources requiring the creation and continued maintenance of records’ (Cox & Duff, 1997: 223). It is suggested that warrant is the most important aspect of the Pittsburgh project calling for additional study. The culture of the organisation can be considered as an aspect of warrant, including the industry in which the organisation is based and country in which the organisation is situated. Elizabeth Yakel (1996) also discusses the importance of organisational culture in recordkeeping and considers Duranti’s work on diplomatics in the cultural context.

Research into ethical issues which will have an effect on the management of information in organisations has been reported within information systems, management and accountancy literature. For example, the effect of national culture on audit practice has been investigated. Tsui and Windsor (2001) compared ethical reasoning in auditors from China and Australia, and the results were consistent with Hofstede’s predictions. Cohen and colleagues (1993) consider possible ethical conflicts for a multinational accounting practice in the context of Hofstede’s dimensions. Ethical attitudes involved in day-to-day decision making by managers have been investigated in a multinational study, differences were found in countries with differing values for Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism and uncertainty avoidance dimensions (Jackson, 2001).

Global information systems, e-commerce initiatives and the existence of multinational enterprises have highlighted differing attitudes and regulatory systems with regard to the protection of personal information. Sandra Milberg and colleagues (1995) conducted research to investigate firstly relationships between nationality, cultural values and privacy concerns, and secondly whether cultural values and privacy concerns are associated with different policy approaches. In doing so they used a continuum model to illustrate the global variation in regulatory approaches – ranging from non-governmental intervention to high governmental involvement. Results from their research indicate that the extent of government involvement is affected by cultural values (p. 71). A relationship between national culture, privacy policy and practice has been confirmed by a number of authors (Ajami, 1990; Cockcroft, 2002; Cockcroft & Clutterbuck, 2001; Duff et al., 2001).

Trans-border data flow legislation (TDFL) is a specific manifestation of privacy concerns. TDFL is designed to check the free flow of certain types of information (including personal information) across national boundaries. Walczuch et al. (1995) state that the main motivation for TDFL is cultural, although there may be other contributing factors. They analyse existing policy and regulatory environments, and relate this analysis to Hofstede’s dimensions. They conclude that the power distance and individualism dimensions appear to correlate with the adoption of TDFL (p. 54).

Walczuch and Steeghs (2001) consider the European Union (EU) directive on data protection legislation in depth and state that is a ‘typically European phenomenon’ (p. 143). However, they emphasise that there are major cultural differences between European nations.

My own research has explored similarities and differences in information management practices between organisations situated in different parts of the world. One study compared three universities situated in Australia, Germany and Hong Kong respectively. Although the functions of these organisations were the same (all were specialist distance education providers) information management in each had quite different features. The main characteristics of each were as follows.

![]() Management of information was not holistic, it was fragmented across the organisation.

Management of information was not holistic, it was fragmented across the organisation.

![]() There was little awareness on the part of individuals of records management responsibilities, and employees showed little trust in the records management systems that were in place.

There was little awareness on the part of individuals of records management responsibilities, and employees showed little trust in the records management systems that were in place.

![]() People complained about information silos.

People complained about information silos.

![]() A technological solution was proposed as the means of fixing all information management problems.

A technological solution was proposed as the means of fixing all information management problems.

![]() People were generally positive about sharing information with colleagues.

People were generally positive about sharing information with colleagues.

![]() There was a disjuncture between society’s and the university’s framework for information management – i.e. a mismatch between external standards and policy.

There was a disjuncture between society’s and the university’s framework for information management – i.e. a mismatch between external standards and policy.

![]() People seemed more inclined to ask a colleague for information rather than consult a documentary resource.

People seemed more inclined to ask a colleague for information rather than consult a documentary resource.

![]() A holistic approach was taken to the management of information, taking into account the needs of all stakeholders, including both staff and students.

A holistic approach was taken to the management of information, taking into account the needs of all stakeholders, including both staff and students.

![]() Efficient and effective systems were in place to share and disseminate information.

Efficient and effective systems were in place to share and disseminate information.

![]() A high value was accorded to information of all types.

A high value was accorded to information of all types.

![]() High importance was accorded to textual information – regarded as authentic and trustworthy.

High importance was accorded to textual information – regarded as authentic and trustworthy.

![]() Explicit links were made between societal requirements and internal policies, i.e. reference made to specific legislative requirements in policy documents.

Explicit links were made between societal requirements and internal policies, i.e. reference made to specific legislative requirements in policy documents.

![]() There were no complaints or comments about information silos.

There were no complaints or comments about information silos.

![]() Staff showed a strong sense of the need to show accountability by keeping records.

Staff showed a strong sense of the need to show accountability by keeping records.

![]() Records management was not viewed as a necessary function.

Records management was not viewed as a necessary function.

![]() There were concerns about the consequences of archiving information because of the perceived risk of unauthorised access to it.

There were concerns about the consequences of archiving information because of the perceived risk of unauthorised access to it.

![]() Staff showed reluctance to share information with colleagues beyond their immediate workgroup.

Staff showed reluctance to share information with colleagues beyond their immediate workgroup.

![]() There was minimal policy or systems relating to information management, which reflected the societal framework.

There was minimal policy or systems relating to information management, which reflected the societal framework.

![]() Shortcomings in information technology systems were addressed by using support staff to manually process information.

Shortcomings in information technology systems were addressed by using support staff to manually process information.

Differences then between the universities were reflected in the:

![]() organisational models (respectively the market, well-oiled machine and family model discussed in Chapter 2);

organisational models (respectively the market, well-oiled machine and family model discussed in Chapter 2);

![]() attitudes to sharing information;

attitudes to sharing information;

![]() preferences for textual or oral information;

preferences for textual or oral information;

![]() the value and recognition accorded to records (information as evidence);

the value and recognition accorded to records (information as evidence);

![]() the ways in which technology was used to manage information;

the ways in which technology was used to manage information;

![]() the information governance models in place (see further discussion in Chapter 6).

the information governance models in place (see further discussion in Chapter 6).

As this was interpretive research, findings cannot be generalised across whole countries. However, this study did highlight areas where organisational culture may influence information management.

In summary, looking at the academic literature it can be seen that although comparatively little research has been undertaken investigating culture in library and recordkeeping disciplines, there is much that is relevant to these areas (such as attitudes to privacy and ethical considerations) in other disciplines.

What is organisational culture?

Before going any further it is important to be very clear about the meaning and nature of organisational culture. Culture is a concept that is the focal point of studies in many different disciplines including anthropology, sociology and psychology. Within information management, culture can be regarded as primarily of interest because of the artefacts that are products of particular cultures, and so is often referred to from a heritage viewpoint. The organisations in which many information managers work may be referred to as ‘cultural heritage’ institutions. Establishing a clear definition of culture that is appropriate to all disciplines and all perspectives is extremely unlikely, and probably attempting to do this undesirable. Therefore I will focus on just one interpretation, which regards culture from a perspective of shared values.

The definition of culture used in this book is that of psychology professor Harry Triandis (1972: 4) of the University of Illinois, who defined culture as a ‘group’s characteristic way of perceiving the man-made part of its environment’. He suggests that this perception is likely to be shared by ‘people who live next to one another, speak the same dialect, and engage in similar activities (e.g. have similar occupations)’ (p. 4). The wording used in this definition acknowledges the possibility of difference between individuals, and does not imply that values are fixed and immutable. This definition is preferred because it emphasises the fact that culture should not only be considered from a geographical perspective, but there are in fact various facets or layers of culture which will be influential. The concept of various layers of culture is further discussed below.

‘Organisational culture’ is a phrase widely and loosely used. The connotations of the phrase are often taken to refer to cultural characteristics that are unique to a particular organisation. People may talk about on the one hand having a ‘good organisational culture’ or even a ‘regular’ organisational culture, and on the other hand a ‘dysfunctional’ or ‘problem’ organisational culture.

This limited view of organisational culture can be traced to the management literature, in particular Tom Peters and Robert Waterman’s 1982 highly influential book In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies. These authors attributed organisational excellence to the existence of a ‘strong’ culture:

Without exception, the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential quality of the excellent companies. Moreover, the stronger the culture and the more it was directed toward the marketplace, the less need was there for policy manuals, organisation charts, or detailed procedures and roles. (p. 75)

Peters and Waterman identified the following factors as the eight attributes of excellence:

In Search of Excellence makes very interesting reading from an information management perspective, not only because it has been influential in creating a partial or misleading view of organisational culture. More significantly, there is much that is explicitly associated with the Peters and Waterman definition of ‘good’ organisational cultures that can be actually detrimental to information management. Written information (such as the detailed procedures and policy manuals mentioned above) is depicted as being a sign of an inadequate culture, so it is likely that records management functions would not be highly valued. With regard to the eight attributes, the last two in particular can actually be seen as negative influences on establishing and maintaining information management services. With respect to the seventh attribute, Peters and Waterman state that: ‘Top-level staffs are lean; it is not uncommon to find a corporate staff of fewer than 100 people running multi-billion-dollar enterprises’ (p. 15).

Information management functions are often part of the central corporate services allocation, so any aspirations for leanness will almost inevitably lead to questioning of the value of associated positions. Unless the organisation concerned has a champion in senior management that will protect and promote information management, this can be a serious risk to survival for information management services.

Similarly, the final attribute signifies that chaos is acceptable, implying that little importance should be placed on establishing or requiring adherence to organisational systems. This type of environment would not be optimal for successful information management, especially the systematic creation and management of records for accountability.

Needless to say, this view of organisational culture is not one that is adopted in this book. Describing organisational cultures as strong or weak has very little meaning. As we will see, what appears ‘good’ in one setting may very well be regarded as completely dysfunctional in another. Nevertheless, it is very important to be aware of this perspective of organisational culture, and indeed the negative effect it can have on information management activities. In discussing organisational cultural issues with management or colleagues, it is worth spending some time making sure that you are not talking at cross purposes. Like it or not, the Peters and Waterman view of organisational culture has certainly made its mark, and it is important to understand it in order to be able to present an alternative, more rounded view.

Moving to the much more holistic approach to organisational culture that we adopt in this book, one very influential scholar who has explored the underlying concepts is Edgar Schein, professor of management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He distinguishes three levels at which cultural analysis can take place: artefacts, beliefs and values, and finally underlying assumptions (Schein, 2004: 25–37). These levels are further described as follows:

![]() Artefacts. A very comprehensive term, denoting all the very diverse phenomena that are readily visible. So, this will include for instance the architecture and interior design of the organisation, its language and ways of communicating, its technologies, the stories that circulate about past and present employees and leaders. Schein also classifies the more formal aspects of the workplace as artefacts – such as processes, procedures and organisational charts.

Artefacts. A very comprehensive term, denoting all the very diverse phenomena that are readily visible. So, this will include for instance the architecture and interior design of the organisation, its language and ways of communicating, its technologies, the stories that circulate about past and present employees and leaders. Schein also classifies the more formal aspects of the workplace as artefacts – such as processes, procedures and organisational charts.

![]() Beliefs and values. Schein identifies these as strategies, goals and philosophies. He stresses the importance of the beliefs and values that are promulgated in the organisation to be based on prior learning on the part of employees. If this is not the case, the beliefs and values may only influence what is said in a given situation, rather than what is actually done.

Beliefs and values. Schein identifies these as strategies, goals and philosophies. He stresses the importance of the beliefs and values that are promulgated in the organisation to be based on prior learning on the part of employees. If this is not the case, the beliefs and values may only influence what is said in a given situation, rather than what is actually done.

![]() Underlying assumptions. These are the taken-for-granted norms that people may have very little awareness of simply because they are so fundamental to the way that things are done. Consequently they can be extremely difficult to change. To illustrate, Schein refers to an engineer deliberately designing a product as unsafe as an inconceivable example of a flawed underlying assumption.

Underlying assumptions. These are the taken-for-granted norms that people may have very little awareness of simply because they are so fundamental to the way that things are done. Consequently they can be extremely difficult to change. To illustrate, Schein refers to an engineer deliberately designing a product as unsafe as an inconceivable example of a flawed underlying assumption.

I will refer back to artefacts in particular later in Chapter 5, but the model that we will use for organisational culture as a concept is one that explicitly takes into account the external setting of the organisation. The approach is that organisational culture is a comprehensive term, which encompasses features that reflect the geographical situation of the organisation, the occupations of the people that work within it, as well as any other cultural characteristics that are unique to that specific institution.

This book will focus on organisational culture in its widest possible sense, that is including the main cultural influences which will impact in one way or another on work within an organisation. This acknowledges that the values and beliefs of individuals will not be solely created or even shaped by the organisation in which they work. This is acknowledged in Schein’s ‘underlying assumptions’, and explicitly linked to national culture by the Dutch anthropologist Geert Hofstede. Hofstede is best known for developing a model for the measurement of national cultural dimensions, which we will consider in some detail in Chapter 2. Hofstede’s theory relating to national culture is subject to considerable debate, which can detract from the insight that his work has contributed to understanding organisational culture. For this reason, it is worthwhile at this initial stage to present the main features relating to Hofstede’s study, and in particular the main criticisms, as a prelude to introducing his organisational culture theory which underpins the thinking in this book.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, surveys were conducted to measure the attitudes of employees of IBM in over 70 countries. The analysis of the data that was collected from these surveys formed the basis of Hofstede’s theory relating to the fundamental influences on our behaviour. Hofstede has described these influences as ‘software of the mind’ and provides the following explanation of his thinking:

… people carry ‘mental programs’ that are developed in the family in early childhood and reinforced in schools and organisations, and … these mental programs contain a component of national culture. They are most clearly expressed in the different values that predominate among people from different countries. (Hofstede, 2001, p. xix)

Hofstede’s research has been the subject of criticism and debate, as well as replication and application. Other models of national culture will be described in Chapter 2, but Hofstede’s is by far the most extensively cited in academic literature (a search on Google Scholar indicates tens of thousands of cited references to Hofstede’s work). The main areas of criticism of Hofstede’s theory are that:

![]() The cultural dimensions are reflective of the world as it was in the 1970s, and consequently are no longer relevant to today’s environment.

The cultural dimensions are reflective of the world as it was in the 1970s, and consequently are no longer relevant to today’s environment.

![]() The survey population of IBM, being largely white collar, middle class employees, cannot be considered as representative of entire nations.

The survey population of IBM, being largely white collar, middle class employees, cannot be considered as representative of entire nations.

![]() A questionnaire on its own was insufficient to gather information relating to values (Sondergaard, 1994).

A questionnaire on its own was insufficient to gather information relating to values (Sondergaard, 1994).

The first two criticisms can be countered with reference to the considerable number of surveys in wide-ranging settings that have been conducted subsequently, using Hofstede’s methodology. For example, a much more recent large-scale study which included 43 countries indicated considerable replicability from the previous value surveys covering large numbers of countries (Smith et al., 1996).

The final criticism relating to reliance on a questionnaire rather than more in-depth interviews to gather data is recognised by Hofstede himself and he recognises the need for, and encourages, other approaches:

The ideal study of culture would combine idiographic and nomothetic, emic and etic, qualitative and quantitative elements … The nomothetic approach in the present study is a consequence of the type of data that became available … The idiographic element in my research is that I had frequently visited and interacted intensively with a fair number of the participating national IBM subsidiaries during the organisation of the first survey cycle. My interpretations of the scores found are often based on personal observations and profound discussions with locals of different ranks … I admire other, more idiographic and qualitative approaches. (Hofstede, 2001: 26)

There is also a more fundamental criticism of Hofstede’s work that applies to all national cultural models: these research findings over-simplify culture by equating it with nations.

There are indeed obvious limitations when defining culture by equating it with a nation. Nations are not fixed and immutable; political changes, particularly in Europe, have demonstrated that to us all too clearly. A political entity identified as a nation or country is likely to be made up of a number of distinct ethnic groups which may be characterised by different value sets. It must therefore be emphasised that at the organisational level, it is recognised that employees will of course hold values representative of particular ethnic, religious and linguistic groupings within that nation. Hofstede clearly acknowledges the existence of such subcultures.

Finally it must be noted that Hofstede’s theory does not apply to individuals per se, but rather reflects the tendency or likelihood to hold certain values. It is important to remember the meaning of Hofstede’s model, and guard against making the erroneous assumptions that:

![]() All members of a culture homogeneously carry the same cultural attributes, that a culture can be uniform.

All members of a culture homogeneously carry the same cultural attributes, that a culture can be uniform.

![]() Values and behaviour of all individuals will be wholly determined by their cultural background.

Values and behaviour of all individuals will be wholly determined by their cultural background.

![]() Dimensions are direct measures of national culture – they are not, they are manifestations of national culture (Williamson, 2002).

Dimensions are direct measures of national culture – they are not, they are manifestations of national culture (Williamson, 2002).

The model of culture referred to by Geert Hofstede and colleagues in a 1990 study is the one that underpins the approach to organisational culture in this book. Similar to Schein’s approach, these authors describe a multilevel model, identifying three layers of culture which are influential in organisations (Hofstede et al., 1990).

The initial layer I will refer to for the sake of simplicity as national culture, where the values acquired growing up from family and school influence attitudes and activities. The middle layer is occupational culture – those values and practices which have been learned in the course of vocational education and training. The most superficial layer reflects those characteristics that are unique to the organisation, the corporate culture. The sector or industry that the organisation is engaged in will be significant, as will the occupational groupings working inside the organisation. Each of these layers will be considered in detail in the rest of the book.

Hofstede (2001: 11) portrays the manifestations of culture as layers around a core of values. Detmar Straub and co-authors (2002) take this a step further and use an analogy of a virtual onion, where the layers are permeable and do not have a given order or sequence, to convey the complexity and lack of predictability of an individual’s cultural characteristics (p. 14). There has been very little research into the relative influences of these cultural layers. What must be emphasised at the outset, therefore, is that the degree of prevalence of one layer over another is not pre-determined. Depending on the setting, the relative influences of the various layers will vary greatly.

Summary and conclusions

Organisational culture has a profound influence on the way in which information is managed. Values and attitudes to information within organisations reflect its information culture; assessment of the information culture is dependent upon understanding the organisational culture.

The concept of organisational culture is widely referred to and discussed, but understanding and interpretation varies enormously. The definition frequently found in management literature of a strong or good organisational culture is not helpful and may even be detrimental to successful information management. The approach taken to organisational culture in this book follows that of Hofstede in distinguishing three levels of cultural characteristics which will shape the overall organisational culture: national, occupational and corporate culture. The relative importance of these three levels is not clear cut, and will vary according to the setting of the workplace. In the next chapter I will look in more detail at the first of these layers: national culture.

References

Ajami, R. Transborder data flow: global issues of concern, values and options. In: Lundstedt S.B., ed. Telecommunications, Values, and the Public Interest. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1990:126–143.

Bearman, D. Diplomatics, Weberian bureaucracy, and the management of electronic records in Europe and America. American Archivist. 1992; 55(1):168–181.

Buckland, M.K., Gathegi, J.N. International aspects of LIS research. In: McClure C.R., Hernon P., eds. Library and Information Science Research: Perspectives and strategies for improvement. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1991:63–71.

Budd, J.M. The organizational culture of the research university: Implications for LIS education. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. 1996; 37(2):154–162.

Calvert, P.J. International variations in measuring customer expectations. Library Trends. 2001; 49(4):732–753.

Cockcroft, S. Gaps between policy and practice in the protection of data privacy. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application. 2002; 4(3):1–13.

Cockcroft, S., Clutterbuck, P., Attitudes towards information privacy. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 12th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Coffs Harbour, NSW, 2001.

Cohen, J.R., Pant, L.W., Sharp, D.J. Culture- based ethical conflicts confronting multinational accounting firms. Accounting Horizons. 1993; 7(3):1–13.

Cox, R.J., Duff, W.M. Warrant and the definition of electronic records: questions arising from the Pittsburgh Project. Archives and Museum Informatics. 1997; 11(3/4):223–231.

Danton, J.P. The Dimensions of Comparative Librarianship. Chicago: American Library Association; 1973.

Duff, W.M., Smielauskas, W., Yoos, H. Protecting privacy. Information Management Journal. 2001; 35(2):14–30.

Gallupe, R.B., Tan, F. A research manifesto for global information management. Journal of Global Information Management. 1999; 7(3):5.

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001.

Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D.D., Sanders, G. Measuring organizational cultures: a qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1990; 35(2):286–316.

Jackson, T. Cultural values and management ethics: A 10 nation study. Human Relations. 2001; 54(10):1267–1302.

Ketelaar, E., The difference best postponed? Archivaria 1997; 44:142–148. www.hum.uva.nl/bai/home/eketelaar/difference.doc

Ketelaar, E. Archivalisation and archiving. Archives and Manuscripts. 1999; 27(1):54–61.

Ketelaar, E. Ethnologie archivistique. Gazette des Archives. 2001; 192:7–20.

Ketelaar, E. ‘Control through communication’ in a comparative perspective. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the First International Conference on the History of Records and Archives (I-CHORA) (forthcoming), 2005.

McSwiney, C. Cultural implications of a global context: the need for the reference librarian to ask again ‘who is my client?’. Australian Library Journal. 2003; 52(4):379–388.

Milberg, S.J., Burke, S.J., Smith, J., Kallman, E.A. Values, personal information privacy, and regulatory approaches. Communications of the ACM. 1995; 38(12):65–74.

Peters, T.J., Waterman, R.H. In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies. New York: Harper & Row; 1982.

Rowley, J. Knowledge management – the new librarianship? From custodians of history to gatekeepers to the future. Library Management. 2003; 24(8/9):433–440.

Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

Smith, P.B., Dugan, S., Trompenaars, F. National culture and the values of organizational employees: A dimensional analysis across 43 nations. Journal of Cross- Cultural Psychology. 1996; 27(2):231–264.

Sondergaard, M. Hofstede’s consequences: A study of reviews, citations and replications. Organization Studies. 1994; 15(3):447–456.

Straub, D., Loch, K., Evaristo, R., Karahanna, E., Srite, M. Toward a theory-based measurement of culture. Journal of Global Information Management. 2002; 10(1):13–24.

Triandis, H.C. The Analysis of Subjective Culture. New York: Wiley; 1972.

Tsui, J., Windsor, C. Some cross-cultural evidence on ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics. 2001; 31(2):143–150.

Walczuch, R.M., Singh, S.K., Palmer, T.S. An analysis of the cultural motivations for transborder data flow legislation. Information Technology and People. 1995; 8(2):37–57.

Walczuch, R.M., Steeghs, L. Implications of the new EU Directive on data protection for multinational corporations. Information Technology and People. 2001; 14(2):142–162.

Williamson, D. Forward from a critique of Hofstede’s model of national culture. Human Relations. 2002; 55(11):1373–1395.

Yakel, E. The way things work: Procedures, processes, and institutional records. American Archivist. 1996; 59:454–464.