Chapter 1

Introducing Project Management

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

1.01 The PMBOK Guide, This Book, and the PMP Exam

1.02 Defining What a Project Is—and Is Not

1.03 Defining Project Management

1.04 Examining Related Areas of Project Management

1.05 Revving Through the Project Life Cycle

1.06 Defining Project Management Data and Information

![]() Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill

Q&A Self Test

How you’ll do on your PMP examination depends on your experience, your ability to problem-solve, and your foundation in project management. This chapter aims to explain how both this book and the sixth edition of PMI’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (referred to the PMBOK Guide in this book) can help you grasp what you must know to pass the exam.

In addition to learning about the PMBOK (pronounced pim-bok) Guide and the exam, you’ll learn what a project is, how project management works, what the exam process itself looks like, and how project management and projects operate in different environments. We’ll also take a “big picture” look at the project charter and the project management plan. We’ve lots to do, so let’s go!

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 1.01

The PMBOK Guide, This Book, and the PMP Exam

If you’ve sat down to read the PMBOK Guide, you’ve obviously had a lot of time on your hands, you were really curious about it, or someone told you it was required reading for passing the Project Management Professional (PMP) examination. Here’s the truth about the PMBOK Guide: It’s boring. My apologies to all my friends at Project Management Institute (PMI), but it’s true. The PMBOK Guide is, however, concise, organized, and an excellent reference manual. I use it all the time. But it wasn’t written to be a thriller. The PMBOK Guide is an excellent book to use as a reference throughout your project management career.

The PMBOK Guide isn’t just made-up stuff from some project management theorists. It’s written by project management professionals from a variety of disciplines. The PMBOK Guide is considered a standard for project management—the terms, processes, and approaches are applicable to nearly all projects nearly all of the time. Sure, you may have projects in which you’ll need to do something different from what the PMBOK Guide advises, but those moments will probably be rare. The PMBOK Guide is written in very broad terms—it’s not a mandate, but a documentation of what’s most likely to happen in most projects.

The sixth edition of the PMBOK Guide will be referenced throughout this book. Why? Well, your PMP exam is largely based on the facts, figures, and subtleties of the current PMBOK Guide. The good news is that unlike the PMBOK Guide—fine book that it is—the book you have in your hands is written in plain language. This book, unlike the PMBOK Guide, focuses on how to pass the PMP exam. It will also help you be a better project manager and explain some mysterious formulas and concepts, but its main goal is to get you over the hump toward those three glorious letters: PMP.

All About the PMBOK Guide

The PMBOK Guide is, as its abbreviated name suggests, a guide, not the end-all-be-all of project management. It’s based on what’s generally recognized as good practice on most projects most of the time. It’s not specific to IT, construction, software development, manufacturing, or any other discipline, but it is applicable to any industry, any project, and any project manager.

For the most part, if you follow the PMBOK Guide, you’ll increase your odds of project success. That means you’ll be more likely to complete the project scope, reach the cost objectives of your project’s budget, and achieve those schedule commitments to which your project must adhere. But there’s no guarantee.

Throughout this book, you’ll see little tips like this one. These tips are here to cheer you on, get you moving, and remind you that you can do this. Create a strategy to study this book and the PMBOK Guide, and keep working toward your goal of earning the PMP.

The PMBOK Guide readily admits that not everything in it should be applied to every conceivable project. That just wouldn’t make sense. Consider a small project to swap out all of the workstation lights in an office building versus a project to build a skyscraper. Guess which one needs more detail and will likely implement more of the practices the PMBOK Guide defines? The skyscraper project, of course.

In the PMBOK Guide, sixth edition, PMI tells us that the PMBOK Guide is based on The Standard for Project Management, another PMI publication that walks through the five process groups of project management (Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing). In the PMBOK Guide, sixth edition, you’ll see that The Standard for Project Management is now included as part of the PMBOK Guide—something new in this edition of the PMBOK Guide.

So, what’s the difference between the PMBOK Guide and The Standard for Project Management? There is much overlap between the two publications, but the PMBOK Guide offers much more detail on project management concepts, trends, tailoring the processes, and insight to the tools and techniques of project management. The Standard for Project Management is a foundational publication that describes, not prescribes, the most common, best practices of project management. This book, and your PMP exam, will focus on the contents of the PMBOK Guide, not The Standard for Project Management.

All About This Book

Your PMP examination is based largely on the PMBOK Guide. As mentioned, the PMBOK Guide is not a study guide; this book is. The following explains what this book will do for you:

![]() Cover all of the objectives as set by PMI for the PMP examination

Cover all of the objectives as set by PMI for the PMP examination

![]() Focus only on exam objectives

Focus only on exam objectives

![]() Prep you to pass the PMP exam, not just take it

Prep you to pass the PMP exam, not just take it

![]() Encapsulate exam essentials for each exam objective

Encapsulate exam essentials for each exam objective

![]() Offer 950 PMP total practice questions

Offer 950 PMP total practice questions

![]() Serve as a handy project management reference guide

Serve as a handy project management reference guide

![]() Not be boring

Not be boring

Every chapter in this book correlates to a chapter in the PMBOK Guide. If you have a copy of the PMBOK Guide, blow the dust off it and flip through its 13 chapters. Now flip through this book, and you’ll see that it covers the same 13 chapters in the same order. And there’s a magical Chapter 14. Okay, it’s not magical, but it explains in detail the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, which is a major exam objective. Chapter 14 covers leadership, motivation, and how to balance stakeholder interests. Chapter 14 also introduces the concept of project priorities and dealing with cultural issues.

Each chapter is full of exciting, action-packed, and riveting information. Well, that’s true if you find the PMP exam exciting, action-packed, and riveting. Anyway, each chapter covers a specific topic relevant to the PMP exam. The first 3 chapters of this book offer a big-picture view of project management, while the remaining 11 chapters are most specific to the PMP exam.

In each chapter, you’ll find an “Inside the Exam” sidebar. This is what I consider to be the most important message from the chapter. At the end of the chapter, you’ll find a quick summary, key terms, and a two-minute drill that recaps all the major points of the chapter. Then you’ll be given a 25-question exam that’s specific to that chapter.

All About the PMP Exam

Not everyone can take the PMP exam—you have to qualify to take it. And this is good. The project management community should want the PMP exam to be tough, the application process to be rigorous, and the audits to be thorough. All of this will help elevate the status of the PMP and ensure that it doesn’t fall prey to the “paper certifications” other professions have seen.

There are two paths to earn the PMP: with a degree or without a degree, as shown in Figure 1-1. With a degree, you’ll need 36 non-overlapping months of project management experience and 4500 hours leading project management tasks within the last eight years. Without a degree, you’ll need 60 non-overlapping months of project management experience and 7500 hours of project management tasks within the last eight years. Note that non-overlapping months of project management experience means that if you’re managing two projects at the same time for 6 months, that’s just 6 months of project management experience—not 12 months of experience.

FIGURE 1-1 There are two paths to qualify for the PMP examination.

In addition to these requirements, you’ll need 35 contact hours of project management education. (My company, Instructing.com, is a PMI Registered Education Provider, and I teach a qualified PMP Exam Prep course online that’s accepted by PMI. Check out the course at www.instructing.com.) Finally, you’ll have to pass the 4-hour exam and then maintain your PMP credential with ongoing education.

Here are the major details of the 2018 PMP examination as of this writing. Always check on PMI’s web site to confirm the exam particulars:

![]() PMI doesn’t tell us what the passing score is for the exam—it’s a secret—but the longstanding traditional score is 61 percent. The exam has 200 multiple-choice questions, 25 of which don’t actually count toward your passing score. These 25 questions are scattered throughout your exam and are used to collect statistics regarding student responses to see if they should be incorporated into future examinations. So this means you’ll actually have to answer 106 correct questions out of 175 live questions.

PMI doesn’t tell us what the passing score is for the exam—it’s a secret—but the longstanding traditional score is 61 percent. The exam has 200 multiple-choice questions, 25 of which don’t actually count toward your passing score. These 25 questions are scattered throughout your exam and are used to collect statistics regarding student responses to see if they should be incorporated into future examinations. So this means you’ll actually have to answer 106 correct questions out of 175 live questions.

![]() Clear and factual evidence of project management experience must be shown in each process group. On your PMP exam application, you’ll have to provide specifics on tasks you’ve completed in a process group. (See Table 1-1 for specific examples from PMI.)

Clear and factual evidence of project management experience must be shown in each process group. On your PMP exam application, you’ll have to provide specifics on tasks you’ve completed in a process group. (See Table 1-1 for specific examples from PMI.)

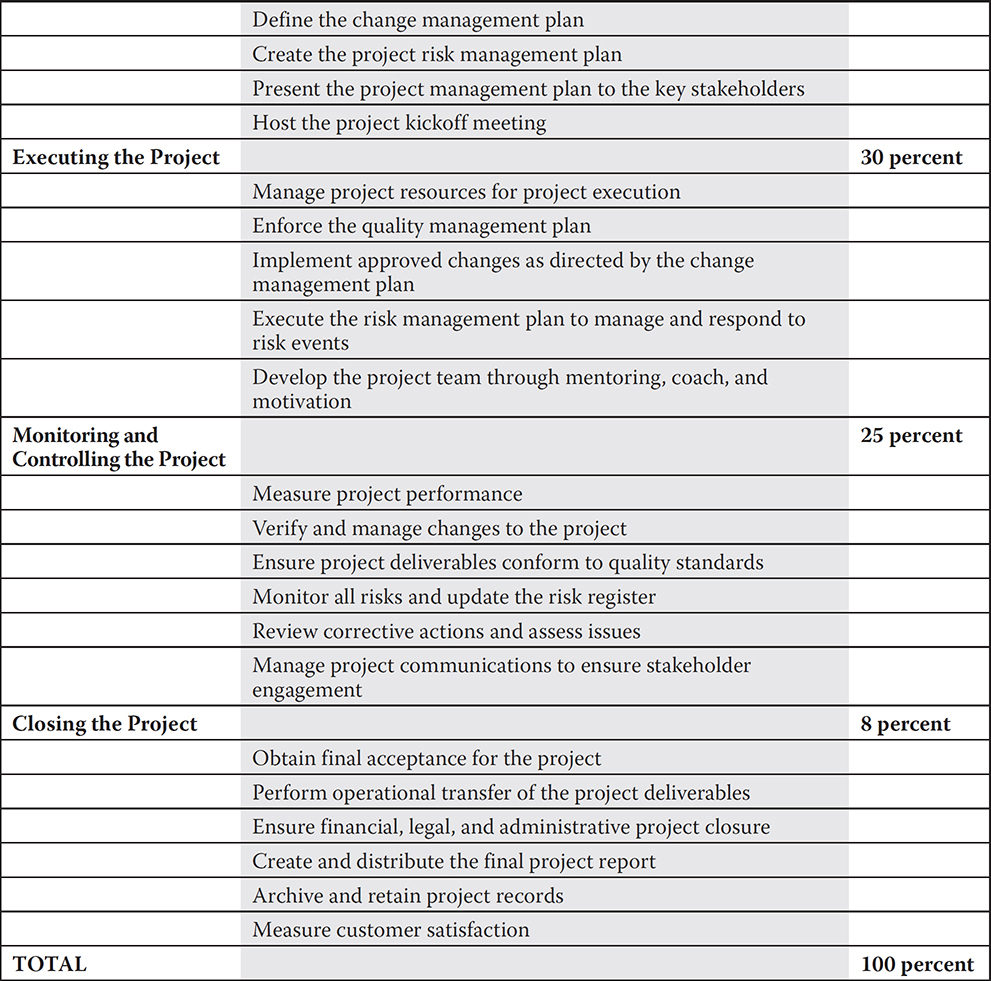

TABLE 1-1 The Five Domains of Experience Needed to Pass the PMP Exam

![]() Each application is given an extended review period. If your application needs an audit, you’ll be notified via e-mail. Audits are completely random, and there’s nothing you can do to avoid an audit. Audits confirm your work experience and education.

Each application is given an extended review period. If your application needs an audit, you’ll be notified via e-mail. Audits are completely random, and there’s nothing you can do to avoid an audit. Audits confirm your work experience and education.

![]() Applicants must provide contact information for supervisors on all projects listed on their PMP exam application. In the past, applicants did not have to provide project contact information unless their application was audited. Now each applicant must give project contact information as part of the exam application.

Applicants must provide contact information for supervisors on all projects listed on their PMP exam application. In the past, applicants did not have to provide project contact information unless their application was audited. Now each applicant must give project contact information as part of the exam application.

![]() Once the application has been approved, candidates have one year to pass the exam. If you procrastinate in taking the exam by more than a year, you’ll have to start the process over.

Once the application has been approved, candidates have one year to pass the exam. If you procrastinate in taking the exam by more than a year, you’ll have to start the process over.

![]() PMP candidates are limited to three exam attempts within one year. If they fail each time during that period, they’ll have to wait one year before resubmitting their exam application.

PMP candidates are limited to three exam attempts within one year. If they fail each time during that period, they’ll have to wait one year before resubmitting their exam application.

Always check the exam details on PMI’s web site: www.pmi.org. They can change this information whenever they like. You can, and should, download the PMP Handbook from www.pmi.org to confirm your study efforts.

The PMP exam will test you on your experience and knowledge in five different areas, as Table 1-1 shows. You’ll have to provide specifics on tasks completed in each knowledge area of your PMP examination application. The preceding domain specifics and their related exam percentages are taken directly from PMI’s web site regarding the PMP examination. Although this information is correct as of this writing, always hop out to www.pmi.org and check the site for any updates as you prepare to pass the PMP exam.

Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct

Right at the beginning of the PMBOK Guide we’re introduced to the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. This code is something that you must read and agree to adhere to when submitting your PMP exam application. The Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct address the values project managers should possess and address—responsibility, respect, fairness, and honesty.

The Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct offers aspirational standards and mandatory standards for all PMI members, volunteers, certificate applicants, and certificate holders, not just PMPs. As a PMP candidate, the code will affect you in your exam application, in your career as a project manager, and in your dealings with vendors, stakeholders, and other project managers. You will encounter ethical questions on the PMP exam, and you’ll always have to choose the best answer, even if you don’t like the choices presented. I’ve included an entire chapter in this book to walk through the particulars of the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 1.02

Defining What a Project Is—and Is Not

Projects are endeavors. Projects are temporary. A project creates something, provides a service, or brings about a result. I know, I know, it sounds like some marriages.

To define a project, you can simply think of some work that has a deadline associated with it, that involves resources, that has a budget to satisfy the scope of the project work, and for which you can state what the end result of the project should be. So, projects are temporary work assignments with a budget, that require some amount of resources (people, equipment, tools, and so on), that require some amount of time to complete, and that create a definite deliverable—a service, result, or product.

Let’s look at project characteristics in more detail.

Projects Create Unique Products, Services, or Results

This one isn’t tough to figure out. Projects have to create a thing, invent a service, or change an environment. The deliverable of the project—a successful project, that is—satisfies the scope that was created way, way back when the project got started. Projects create the following deliverables:

![]() Products Projects can create tangible products such as a skyscrapers or a design for piece of electronics, which is the end of the project. Or projects can create components that contribute to other tangible products, such as a project to design and build a specialized engine for a ship or custom electronics for a prototype device.

Products Projects can create tangible products such as a skyscrapers or a design for piece of electronics, which is the end of the project. Or projects can create components that contribute to other tangible products, such as a project to design and build a specialized engine for a ship or custom electronics for a prototype device.

![]() Services A project creating a service could establish a new call center, an order fulfillment process, or a faster way to complete inventory audits.

Services A project creating a service could establish a new call center, an order fulfillment process, or a faster way to complete inventory audits.

![]() Results Projects can be research driven. Consider a research-and-development project with a pharmaceutical company to find a cure for the common cold.

Results Projects can be research driven. Consider a research-and-development project with a pharmaceutical company to find a cure for the common cold.

![]() Combination And, yes, projects can even be a combination of products, services, and results. There’s no rule that your project can create a product and a service; for example, you might be leading a project to develop a new drug. Developing the drug is the tangible product, creating a lab test that you run for a doctor to diagnose the illness is a service, and the clinical trials to get FDA certification are results.

Combination And, yes, projects can even be a combination of products, services, and results. There’s no rule that your project can create a product and a service; for example, you might be leading a project to develop a new drug. Developing the drug is the tangible product, creating a lab test that you run for a doctor to diagnose the illness is a service, and the clinical trials to get FDA certification are results.

Projects are unique. This means that every project you ever do is different from all the other projects you’ve done in the past. Even if it’s the same basic approach to get to the same end result, there are unique factors within each project, such as the time it takes, the stakeholders involved, the environment in which the project takes place, and on and on. All projects are unique, even if your company does the same type of project repeatedly. Lucky you.

Projects Are Temporary

Regardless of what some projects may seem like, they must be temporary. If the work is not temporary, it is operations. Like a good story, projects have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Projects end when the scope of the project has been met—usually. Sometimes projects end when the project runs out of time or cash or when it becomes clear that the project won’t be able to complete the project objectives, so it’s scrapped. You might also experience the end of the project when it becomes clear that the project is no longer needed, such as when a new technology supersedes the project you’re managing.

The goal of a project will vary based on what the project’s deliverable is, but typically, the result is to create something that’ll be around longer than the process it took to create it. For example, if you’re managing a project to build a skyscraper, you expect the skyscraper to be around much longer than the time it took to build it.

So temporary means that the project is temporary, and the deliverable may or may not be temporary. You can have a project to host a giant picnic for your entire organization and its customers. The project’s logistics, invitations, and coordination of chefs may take months to complete, but the picnic will last only a few hours. However, you could argue that although the picnic event was temporary, the memories and goodwill your picnic created could last a lifetime. (That had better be one good picnic!)

Sometimes temporary describes the market window. We’ve all seen fads come and go over the past years: pet rocks, the dot.com boom, streaking, and more. Projects can often be created that capitalize on fads, which means projects have to deliver fast before the fad fades away and the next craze begins. Fads and opportunities are temporary; projects that feed off these are temporary as well.

When’s the last time you managed a project in which the entire project team stuck with the project through the entire duration? It probably doesn’t happen often. Project teams are often more temporary than the project itself, but, typically, project teams last only as long as the project does. Once the project is complete, the team disbands and the project team members move on to other projects within the organization.

Project teams don’t have to be big groups of people to complete a project. In fact, the PMBOK Guide advises that projects can be completed by even a single person.

Projects Change Things and Environments

When you think about a project—any project—it’s all about change. Any project you’ve ever worked on changed something. You added a server to your work environment? Change. You created a new product for your customers? Change. You led a project to develop a new product? Change again. All projects drive change. In the business world, your projects move the organization from its current state to a desired future state, and projects facilitate that change from now to then. As a general rule, projects can be mapped to a MACD description:

![]() Move A project moves something. You centralized all of your company’s data centers into one location. That’s a move project.

Move A project moves something. You centralized all of your company’s data centers into one location. That’s a move project.

![]() Add A project adds something to the current environment. You lead a project to build a new bridge in your city. That’s adding to the current city’s environment.

Add A project adds something to the current environment. You lead a project to build a new bridge in your city. That’s adding to the current city’s environment.

![]() Change Projects can change the environment. You upgrade your workstations to the latest and greatest operating systems. That’s a change project.

Change Projects can change the environment. You upgrade your workstations to the latest and greatest operating systems. That’s a change project.

![]() Delete Projects can remove things and services from the current environment. You lead an effort to demolish derelict or abandoned houses as part of urban revitalization program. That’s a delete project.

Delete Projects can remove things and services from the current environment. You lead an effort to demolish derelict or abandoned houses as part of urban revitalization program. That’s a delete project.

Projects Create Business Value

Projects need to provide business value. Business value is the sum of the benefits that an organization can quantify. Benefits can usually be defined in financial terms, but they may also be intangible benefits, such as goodwill, brand recognition, benefits to the public, strategic alignment, and even your organization’s reputation. Time savings, a common business value, can be quantified. You’re looking for benefits for stakeholders in the form of monetary assets, equity, utility, fixtures, tools, and market share.

Business value is almost always quantified in financial terms—something that helps set the objectives of the project. You might be asked to predict the profitability of a project to justify the organization’s investment in the project. As you know, projects cost money and time, and you’ll have to justify that investment of resources up front. This is where we’ll get into project selection, return on investment, and whether your project—or any project—should move forward or not.

Consider the Project Initiation Context

In alignment with business value is the discussion of project initiation: Why choose a project at all? For most project managers, this question is out of their scope of responsibilities, but they may get called upon to contribute to the project selection and initiation conversation. As a general practice, there are four reasons why projects get initiated:

![]() Satisfy stakeholder requests, needs, and opportunities

Satisfy stakeholder requests, needs, and opportunities

![]() Meet regulatory requirements, legal requirements, or social requirements

Meet regulatory requirements, legal requirements, or social requirements

![]() Change business and/or technological strategies in the organization

Change business and/or technological strategies in the organization

![]() Improve upon existing products, processes, or services or add new products, processes, and services

Improve upon existing products, processes, or services or add new products, processes, and services

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 1.03

Defining Project Management

Project management is the supervision and control of the work required to complete the project vision. The project team carries out the work needed to complete the project, while the project manager schedules, monitors, and controls the various project tasks. Project management requires that you apply your knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques, and do whatever it takes, generally speaking, to achieve the project objectives. Project management is about getting things done.

Projects, being the temporary and unique things that they are, require the project manager to be actively involved with the project implementation. Projects are not self-propelled. Project management is accomplished by using the correct project management processes at the right time, to the correct depth, and with the correct technique. These processes, which you’ll learn throughout this book, are logically organized in five process groups:

![]() Initiating

Initiating

![]() Planning

Planning

![]() Executing

Executing

![]() Monitoring and controlling

Monitoring and controlling

![]() Closing

Closing

Although the information covered in this chapter is important, it is more of an umbrella of the ten knowledge areas that you’ll want to focus on for your PMP exam. You’ll see all of the 49 project management processes in detail in the upcoming chapters. At the beginning of each chapter, we’ll highlight the processes that the knowledge area deals with. Here’s a breakdown of the 49 processes that you’ll learn about throughout this book.

Initiating the Project

There are just two processes to know for project initiation:

![]() Develop the project charter.

Develop the project charter.

![]() Identify project stakeholders.

Identify project stakeholders.

Planning the Project

There are 24 processes to know for project planning:

![]() Develop the project management plan.

Develop the project management plan.

![]() Plan scope management.

Plan scope management.

![]() Collect project requirements.

Collect project requirements.

![]() Define the project scope.

Define the project scope.

![]() Create the work breakdown structure.

Create the work breakdown structure.

![]() Plan schedule management.

Plan schedule management.

![]() Define the project activities.

Define the project activities.

![]() Sequence the project activities.

Sequence the project activities.

![]() Estimate the activity duration.

Estimate the activity duration.

![]() Develop the project schedule.

Develop the project schedule.

![]() Plan cost management.

Plan cost management.

![]() Estimate the project costs.

Estimate the project costs.

![]() Establish the project budget.

Establish the project budget.

![]() Plan quality management.

Plan quality management.

![]() Plan resource management.

Plan resource management.

![]() Estimate activity resources

Estimate activity resources

![]() Plan communications management.

Plan communications management.

![]() Plan risk management.

Plan risk management.

![]() Identify the project risks.

Identify the project risks.

![]() Perform qualitative risk analysis.

Perform qualitative risk analysis.

![]() Perform quantitative risk analysis.

Perform quantitative risk analysis.

![]() Plan risk responses.

Plan risk responses.

![]() Plan procurement management.

Plan procurement management.

![]() Plan stakeholder engagement.

Plan stakeholder engagement.

Executing the Project

There are ten executing processes:

![]() Direct and manage project work.

Direct and manage project work.

![]() Manage project knowledge.

Manage project knowledge.

![]() Manage quality.

Manage quality.

![]() Acquire resources.

Acquire resources.

![]() Perform team development.

Perform team development.

![]() Manage the team.

Manage the team.

![]() Manage communications.

Manage communications.

![]() Implement risk responses.

Implement risk responses.

![]() Conduct procurements.

Conduct procurements.

![]() Manage stakeholder engagement.

Manage stakeholder engagement.

Monitoring and Controlling the Project

There are 12 monitoring and controlling processes:

![]() Monitor and control the project work.

Monitor and control the project work.

![]() Perform integrated change control.

Perform integrated change control.

![]() Complete scope validation.

Complete scope validation.

![]() Control the scope.

Control the scope.

![]() Perform schedule control.

Perform schedule control.

![]() Perform cost control.

Perform cost control.

![]() Administer quality control.

Administer quality control.

![]() Control resources.

Control resources.

![]() Monitor communications.

Monitor communications.

![]() Monitor risks.

Monitor risks.

![]() Control procurements.

Control procurements.

![]() Monitor stakeholder engagements.

Monitor stakeholder engagements.

Closing the Project

There is only one closing process:

![]() Close out the project or the project phase.

Close out the project or the project phase.

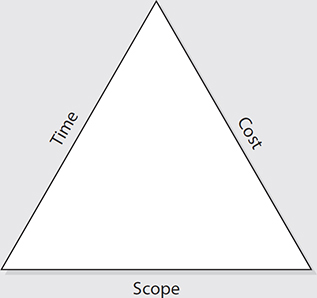

Process Group Interactions

As a project manager you’ll move between these five processes groups as appropriate in the project. Most projects begin with an identification of a business or societal need. Business needs generally focus on improving or maintaining profits, and societal needs include improving living conditions with new roads or cleaner water. This process may include some high-level requirements, costs, value statements, and timelines—what it’ll take for the project to be complete and to be considered successful. Your ongoing concern is to keep the stakeholders satisfied on the project’s progress by communicating the status of the project, showing evidence of progression toward project completion, and keeping the project constraints in balance. A constraint is any factor that limits the parameters of the project. The most common constraints in any project are time, cost, and scope, but you should also consider quality, resources (people, equipment, tools, and the like), and risks. Projects that are poorly managed are plagued by missed deadlines, blown budgets, quality issues, rework, scope expansion, stakeholder turmoil, and overall failure in achieving the project goals. Keep the following in mind:

![]() Process groups are collections of project processes to bring about a specific result.

Process groups are collections of project processes to bring about a specific result.

![]() Process groups are not project phases. The project may follow a workflow through the process groups, but the phases of the project are specific to the actual project work.

Process groups are not project phases. The project may follow a workflow through the process groups, but the phases of the project are specific to the actual project work.

Process groups are iterative. You can use the sequence of processes throughout the entire project, in each phase of the project, or both. I’ll discuss these points throughout the book, but for now this is a good foundation to understand why we all need effective, controlled project management. We achieve that goal through the five process groups and the project management processes. A project will also typically use ten project management knowledge areas. What you do in one knowledge area has a direct effect on the other knowledge areas. Chapters 4 through 13 will explore the following knowledge areas in detail:

![]() Project integration management This knowledge area focuses on creating the project charter, the project scope statement, and a viable project plan. Once the project is in motion, project integration management is all about monitoring and controlling the work. If changes happen—and they will—you have to determine how that change may affect all of the other knowledge areas.

Project integration management This knowledge area focuses on creating the project charter, the project scope statement, and a viable project plan. Once the project is in motion, project integration management is all about monitoring and controlling the work. If changes happen—and they will—you have to determine how that change may affect all of the other knowledge areas.

![]() Project scope management This knowledge area deals with the planning, creation, protection, and fulfillment of the project scope. One of the most important activities in all of project management happens in this knowledge area: creation of the work breakdown structure. Oh, joy!

Project scope management This knowledge area deals with the planning, creation, protection, and fulfillment of the project scope. One of the most important activities in all of project management happens in this knowledge area: creation of the work breakdown structure. Oh, joy!

![]() Project schedule management Schedule management is crucial to project success. This knowledge area covers activities, their characteristics, and how they fit into the project schedule. This is where you and the project team will define the activities, plot out their sequence, and calculate how long the project will actually take.

Project schedule management Schedule management is crucial to project success. This knowledge area covers activities, their characteristics, and how they fit into the project schedule. This is where you and the project team will define the activities, plot out their sequence, and calculate how long the project will actually take.

![]() Project cost management Cost is always a constraint in project management. This knowledge area is concerned with planning, estimating, budgeting, and controlling costs. Cost management is tied to time and quality management—screw up either of these and the project costs will increase.

Project cost management Cost is always a constraint in project management. This knowledge area is concerned with planning, estimating, budgeting, and controlling costs. Cost management is tied to time and quality management—screw up either of these and the project costs will increase.

![]() Project quality management What good is a project that’s done on time if the scope isn’t complete, the work is faulty, or the deliverable is horrible? Well, it’s no good. This knowledge area centers on quality planning, assurance, and control.

Project quality management What good is a project that’s done on time if the scope isn’t complete, the work is faulty, or the deliverable is horrible? Well, it’s no good. This knowledge area centers on quality planning, assurance, and control.

![]() Project resource management This knowledge area focuses on organizational planning, staff acquisition, and team development. You have to acquire your project team, develop this team, and then lead the team to the project results.

Project resource management This knowledge area focuses on organizational planning, staff acquisition, and team development. You have to acquire your project team, develop this team, and then lead the team to the project results.

![]() Project communications management The majority of a project manager’s time is spent communicating. This knowledge area details how communication happens, outlines stakeholder management, and shows how to plan for communications within any project.

Project communications management The majority of a project manager’s time is spent communicating. This knowledge area details how communication happens, outlines stakeholder management, and shows how to plan for communications within any project.

![]() Project risk management Every project has risks. This knowledge area focuses on risk planning, analysis, monitoring, and control. You’ll have to complete qualitative analysis and then quantitative analysis to prepare adequately for project risks. Once the project moves forward, you’ll need to monitor and react to identified risks as planned.

Project risk management Every project has risks. This knowledge area focuses on risk planning, analysis, monitoring, and control. You’ll have to complete qualitative analysis and then quantitative analysis to prepare adequately for project risks. Once the project moves forward, you’ll need to monitor and react to identified risks as planned.

![]() Project stakeholder management Stakeholders are the all people who are affected positively or negatively, or perceived to be, by your project. They can influence your project’s success, because a subset of them defines the projects goals. This knowledge area requires that you and the project team

Project stakeholder management Stakeholders are the all people who are affected positively or negatively, or perceived to be, by your project. They can influence your project’s success, because a subset of them defines the projects goals. This knowledge area requires that you and the project team

![]() identify stakeholders,

identify stakeholders,

![]() plan how you’ll manage their concerns and requirements in the project,

plan how you’ll manage their concerns and requirements in the project,

![]() plan how you’ll manage and control their engagement in the project, and

plan how you’ll manage and control their engagement in the project, and

![]() balance the needs, wants, threats, and concerns that stakeholders introduce to the project with the identified project requirements.

balance the needs, wants, threats, and concerns that stakeholders introduce to the project with the identified project requirements.

![]() Project procurement management Projects often need to procure products, services, and results purchased from outside vendors in order to reach closing. This knowledge area covers the business of project procurement, the processes to acquire and select vendors, and contract negotiation. The contract between the vendor and the project manager’s organization will guide all interaction between the project manager and the vendor.

Project procurement management Projects often need to procure products, services, and results purchased from outside vendors in order to reach closing. This knowledge area covers the business of project procurement, the processes to acquire and select vendors, and contract negotiation. The contract between the vendor and the project manager’s organization will guide all interaction between the project manager and the vendor.

Tailoring the Project Process

Chances are that you follow a prescribed methodology to manage projects where you work. Your work environment uses names for some of these processes that differ slightly from those presented here and in the PMBOK Guide, and that’s perfectly fine. The methodology that your organization uses to manage projects is just that—a method. The PMBOK Guide is not a methodology, but a guide to the best practices of project management.

The flexibility of the PMBOK Guide and project management is beautiful, when you think about it. Okay, maybe “beautiful” isn’t the best word, but the flexibility is important. The processes and approaches that you utilize in your project management approach involves tailoring of the processes, and that’s what’s needed in every project. Tailoring enables you to choose what processes should be used on a project and to what depth the processes should be used.

You do not use every process on every project. The larger the project, the more processes you will likely use. Consider a low-level project to swap out keyboards in an organization. Contrast that to a high-level project to construct a new headquarters for your company. The construction project has more uncertainties and will require more project management processes—and more tailoring of the processes to fit the uniqueness of the project.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 1.04

Examining Related Areas of Project Management

Project management is the administration of activities to change the current state of an organization into a desired future state. It manages a complex relationship between decision-making, planning, implementation, control, and documentation of the experience from start to finish. In addition to traditional project management, you may encounter, have encountered, or are actively participating in related areas. These related aspects often are superior to individual project management, are part of project management, or equate to less than the management of any given project.

Organizational project management (OPM) is an organizational approach to coordinate, manage, and control projects, programs, and portfolio management in a uniform, consistent effort. The philosophy of OPM is that by doing all work within projects, programs, and portfolio management with the same type of processes, actions, and techniques, the organization will consistently deliver better results than it would if the processes and approach were independent of one another. While project, program, and portfolio each have different skill sets, there is overlap in their approach, and these endeavors may utilize the same resources—including you, the project manager—to accomplish their objectives.

This section dissects the related areas of project management to see how they tie together to change a current state to a desired future state.

Exploring Program Management

Program management is the management of multiple projects all working in unison toward a common goal. Programs achieve benefits by managing projects collectively, rather than independently. Projects within a program can better share resources, improve communications, manage interdependencies, resolve issues quickly, leverage resources, and provide more benefits for the organization than they would if each project were not managed collectively under a program. Projects within a program still have project managers, but the project managers work with, and often report to, the program manager.

Consider all of the work that goes into building a skyscraper, for example. Within the overall work, several projects may lead to the result. You could have a project for the planning and design of the building. Another project could manage the legal, regulatory, and project inspections that would be required for the work to continue. Another project could be the physical construction of the building, and other projects might entail electrical wiring, elevators, plumbing, interior design, and more. Could one project manager effectively manage all of these areas of expertise? Possibly, but probably not.

A better solution could be to create a program that comprises multiple projects. Project managers would manage each of the projects within the program and report to the program manager. The program manager would ensure that all of the integrated projects work together on schedule, on budget, and ultimately toward the completion of the program.

Another example is a program within NASA. NASA could create a program within the organization to explore space, and it comprises individual projects within that program. Each project included in the program has its own goals, initiatives, and objectives that are in alignment with the overall mission of the space program. Programs are a collection of individual projects working in alignment toward a common end.

Basically, programs have much larger scopes than projects do. Project plans and program plans differ in that project plans are often detail-oriented, while program plans are often at a higher level, with the details left to the project teams within the program. Although project managers are usually resistant to change, program managers expect change to happen within the program. Because programs are made up of projects, project managers can expect the program manager to interact regularly with their projects to monitor and control the success of each project. Programs are deemed successful, just like projects, based on their abilities to meet requirements, meet performance objectives, and benefit delivery.

Consider Project Portfolio Management

Portfolios include projects, programs, and even operations that are managed and coordinated and should link to the strategic objectives for the organization, as demonstrated in Figure 1-2. Portfolios are created and controlled by upper-level management and executives and include financial considerations of the investment, return on investment, and distribution of risks for the programs, projects, and operations included in the portfolio. A portfolio describes the collection of investments in the form of projects and programs in which the organization invests capital. Project managers and, if applicable, program managers report to a portfolio review board on the performance of the projects and programs. The portfolio review board may also direct the selection of projects and programs.

FIGURE 1-2 Portfolios can contain operations, programs, and projects.

The portfolio review board—or even the direct management of the organization—also has a scope of projects and programs they’d like to invest in. This scope, however, is at a higher level than the scope of projects and programs, because the endeavors selected by the portfolio review board must fall within the strategic objectives of the company. Investments are made in projects and programs when there is a viable, strategic opportunity. Portfolio managers oversee the portfolio and monitor the organizational and marketplace environments to ensure that the components of the portfolio make sense to continue and to support the organizational objectives.

Consider these elements that may cause an organization to invest in a project or program as part of its portfolio:

![]() Legal requirement

Legal requirement

![]() Compliance needs

Compliance needs

![]() Advancement in technology

Advancement in technology

![]() Change in the market demand

Change in the market demand

![]() Efficiency improvements, business need, or productivity analysis

Efficiency improvements, business need, or productivity analysis

![]() Changes in operational capability

Changes in operational capability

![]() Environmental opportunity

Environmental opportunity

![]() Social need

Social need

The investments the company makes in projects and programs should have, of course, a positive return. These investments are monitored by the portfolio review board and portfolio manager through communications with the program managers and the project managers. The organization wants to see a return on investment through profits, social or performance improvements, reduction in waste, or other key performance indicators established at the selection of the projects and program investment.

While the focus of this book, the PMBOK Guide, and your PMP exam is on project management, it’s nearly impossible to avoid having a discussion on operations. Operations are the day-to-day activities that move a business forward. Projects are unique and temporary, while operations are not. Operations, programs, and projects overlap and work with one another, not opposed to one another. For your exam, you won’t need to know much about operations, other than that operations are ongoing. Portfolios can include, to be clear, operational activities, but our focus will be on the projects and programs within the portfolios.

Portfolio projects could be interdependent, but they don’t have to be. A portfolio is not the same as a program; it is a collection of projects, programs, and operations. The projects in a portfolio could be within one line of business, could be based on the strategies within an organization, or could follow the guidance of one director within an organization. There is a balance of risk in the selection of projects and programs. It’s not unusual to have some low-risk, high-risk, and moderate-risk selections to distribute the risk exposure across the components.

Project selections may pass through a project selection committee or a project steering committee, where executives will look at the return on investment, the value of the project, risks associated with taking on the project, and other attributes of the project. This is all part of project portfolio management.

Portfolios, programs, and projects obviously interact, but they each have a different purpose. A term you might occasionally see is organizational project management (OPM). OPM is the ideal model an organization uses when coordinating the efforts, goals, strategies, and investments of time and resources into portfolios, programs, and projects. An organizational strategic plan defines what investments should be made where, the expected return on investment, the risk distribution of each investment, and how each investment (the portfolio, program, or project) will contribute to the project’s achievement of benefits.

Implementing Subprojects

Subprojects are an alternative to programs. Some projects may not be wieldy enough to require the creation of a full-blown program, yet they may be large enough that some of the work can be delegated to a subproject. A subproject exists under the parent project, but it follows its own schedule for completing one or more deliverables. Subprojects may be outsourced, assigned to other project managers, or managed by the parent project manager but with a different project team. The following illustration shows a project containing multiple subprojects.

Subprojects are often areas of a project that are outsourced to vendors. For example, if you were managing a project to create a new sound system for home theaters, a subproject could be the development of the user manual included with the sound system. You would thus hire writers and graphic designers to work with your project team. The writers and designers would learn all about the sound system and then retreat to their own spaces to create the user manual according to their project methodology. The deliverable of their subproject would be included in your overall project plan, but the actual work done to complete the manual would not be in your plan. You’d simply allot the funds and time required by the writers and graphic designers to create the manual.

Subprojects do, however, follow the same quality guidelines and expectations of the overall project. The project manager has to work with the subproject team regarding supplying any needed materials, scheduling, value, and cost to ensure the deliverables and activities of the subproject integrate smoothly with the “master” project.

Projects vs. Operations

Meet Jane. Jane is a project manager for her organization. Vice presidents, directors, and managers with requests to investigate or to launch potential projects approach her daily—or so it seems to Jane. Just this morning, the sales manager met with Jane because he wants to implement a new direct-mail campaign to all of the customers in the sales database. He wants this direct-mail campaign to invite customers to visit the company web site to see the new line of products. Part of the project also requires that the company web site be updated so that it’s in sync with the mailing. Sounds like a project, but is it really? Could this actually be just a facet of an ongoing operation?

In some organizations, everything is a project. In other organizations, projects are rare exercises in change. There’s a fine line between projects and operations, and often these separate entities overlap in function. Consider the following points shared by projects and operations:

![]() Both involve employees.

Both involve employees.

![]() Both typically have limited resources: people, money, or both.

Both typically have limited resources: people, money, or both.

![]() Both are hopefully designed, executed, and managed by someone in charge.

Both are hopefully designed, executed, and managed by someone in charge.

Jane has been asked to manage a direct-mail campaign to all of the customers in the sales database. Could this be a project? Sure—if this company has never completed a similar task and there are no internal departments that do this type of work as part of their regular activities. Often, projects are confused with general business duties: marketing, sales, manufacturing, and so on. The tell-tale sign of a project is that it has an end date and that it’s unique from other activities within the organization. Here are some examples of projects:

![]() Designing a new product or service

Designing a new product or service

![]() Converting from one computer application to another

Converting from one computer application to another

![]() Building a new warehouse

Building a new warehouse

![]() Moving from one building to another

Moving from one building to another

![]() Organizing a political campaign

Organizing a political campaign

![]() Designing and certifying a new airplane

Designing and certifying a new airplane

The end results of projects can result in operations. For example, imagine a company creating a new airplane. This new airplane will be a small personal plane that would enable people to fly to different destinations with the same freedom they use in driving their cars. The project team will have to design an airplane from scratch that would be similar to a car, so that consumers could easily adapt and fly to Sheboygan at a moment’s notice. The project to create a personal plane is temporary, but not necessarily short-term. It may take years to go from concept to completion—but the project does have an end date. A project of this magnitude may require hundreds of prototypes and years of certification before a working model is ready for the marketplace. In addition, there are countless regulations, safety issues, and quality control concerns that must be pacified before completion.

Once the initial plane is designed, built, and approved, the end result of the project is business operations. As the company creates a new vehicle, they would follow through with the design by manufacturing, marketing, selling, supporting, and improving the product. The initial design of the airplane is the project—the business of manufacturing it, supporting sold units, and marketing the product constitutes the ongoing operations part of business.

In the creation of the plane, before the manufacturing of the actual plane begins, the project manager would have to involve the operational stakeholders in the project. The project manager needs the expertise of the people who’ll be doing the day-to-day operations of the plane manufacturing. Although operations and projects are different, they are also reliant on one another in most projects. The project deliverables often have a direct impact on the day-to-day operations of the organization. Communication and coordinated planning is needed between the project manager and the operational stakeholders.

Operations are the day-to-day work that goes on in the organization. A manufacturer manufactures things, scientists complete research and development, and businesses provide goods and services. Operations are the heart of organizations. Projects, on the other hand, are short-term endeavors that fall outside of the normal day-to-day operations an organization offers.

Let’s be realistic. In some companies, nearly everything’s a project. This is probably true if you work in an organization that completes projects for other companies. That’s fine and acceptable, however, since you’re participating in management by projects. There are still many operational activities that exist in these companies, such as accounting, payroll and HR, sales, marketing, and the like.

Once the project is complete, the project team moves along to other projects and activities. The people who are actually building the airplanes on the assembly line, however, have no end date in sight and will continue to create airplanes as long as there’s a demand for the product.

Projects and Business Value

Projects must support the corporate vision, mission, and objectives or they don’t bring value to the organization. Business value is simply what the organization is worth; it is the sum of the tangible and intangible components of an organization. Tangible elements are easy to identify: cash, assets, equipment, real estate, and so on. Intangible elements are things like reputation, the company brand, and trademarks. Projects must contribute to the business value or they likely don’t fit within the strategic goals of the company.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 1.05

Revving Through the Project Life Cycle

Consider any project, and you’ll also have to consider any phases within the project. Construction projects have definite phases. IT projects have definite phases. Marketing, sales, and internal projects all have definite phases. Projects—all projects—comprise phases. Phases make up the project life cycle, and they are unique to each project. Furthermore, organizations, project managers, and even project frameworks such as Agile or Scrum can define phases within a project life cycle. Just know this: The sum of a project’s phases equates to the project’s life cycle.

In regard to the PMP exam, it’s rather tough for the PMI to ask questions about specific project life cycles. Why? Because every organization may identify different phases within all the different projects that exist. Bob may come from a construction background and Susan from IT, each one being familiar with totally different disciplines and totally different life cycles within their projects. However, all PMP candidates should recognize that every project has a life cycle—and all life cycles comprise phases.

Because every project life cycle is made up of phases, it’s safe to assume that each phase has a specific type of work that enables the project to move toward to the next phase in the project. When we talk in high-level terms about a project, we might say that a project is launched, planned, executed, and finally closed, but it’s the type of work, the activities the project team is completing, that more clearly define the project phases. In a simple construction example, this is easy to see:

![]() Phase 1: Planning and prebuild

Phase 1: Planning and prebuild

![]() Phase 2: Permits and filings

Phase 2: Permits and filings

![]() Phase 3: Prep and excavation

Phase 3: Prep and excavation

![]() Phase 4: Basement and foundation

Phase 4: Basement and foundation

![]() Phase 5: Framing

Phase 5: Framing

![]() Phase 6: Interior

Phase 6: Interior

![]() Phase 7: Exterior

Phase 7: Exterior

Typically, one phase is completed before the next phase begins; this relationship between phases is called a sequential relationship. The phases follow a sequence to reach project completion—one phase after another. Sometimes project managers allow phases to overlap because of time constraints, cost savings, and smarter work. When time’s an issue and a project manager allows one phase to begin before the last phase is completed, it’s called an overlapping, or parallel, relationship because the phases overlap. You might also know this approach as fast tracking. Fast tracking, as handy as it is, increases the risk within a project.

A project is an uncertain business—the larger the project, the more uncertainty. It’s for this reason, among others, that projects are broken down into smaller, more manageable phases. A project phase allows a project manager to see the project as a whole and yet still focus on completing the project one phase at a time. You can also think of the financial distribution and the effort required in the form of a project life cycle. Generally, labor and expenses are lowest at the start of the project, because you’re planning and preparing for the work. You’ll spend the bulk of the project’s budget on labor, materials, and resources during project execution, and then costs will taper off as your project eases into its closing.

Working with a Project Life Cycle

Projects are like snowflakes: No two are alike. Sure, sure, some may be similar, but when you get down to it, each project has its own unique attributes, activities, and requirements from stakeholders. One attribute that typically varies from project to project is the project life cycle. As the name implies, the project life cycle determines not only the start of the project, but also when the project should be completed. All that stuff packed in between starting and ending? Those are the different phases of the project.

In other words, the launch, a series of phases, and project completion make up the project life cycle. Each project will have similar project management activities, but the characteristics of the project life cycle will vary from project to project.

Completing a Project Feasibility Study

The project’s feasibility is part of the initiating process. Once the need has been identified, a feasibility study is introduced into the plan to determine if the need can realistically be met.

Project feasibility studies can be a separate project.

So how does a project get to be a project? In some organizations, it’s pure luck. In most organizations, however, projects may begin with a feasibility study. Feasibility studies can be, and often are, part of the initiation process of a project. In some instances, however, a feasibility study may be treated as a stand-alone project.

Let’s assume that the feasibility of Project ABC is part of the project initiation phase. The outcome of the feasibility study may tell management several things:

![]() Whether the concept should be mapped into a project

Whether the concept should be mapped into a project

![]() If the project’s concept will deliver the anticipated value

If the project’s concept will deliver the anticipated value

![]() The expected cost and time needed to complete the concept

The expected cost and time needed to complete the concept

![]() The benefits and costs to implement the project concept

The benefits and costs to implement the project concept

![]() A report on the needs of the organization and how the project concept can satisfy these needs

A report on the needs of the organization and how the project concept can satisfy these needs

There is a difference between a feasibility study and a business case. A feasibility study examines the potential project to see if it’s feasible to do the project work. A business case examines the financial aspect of the project to see if the project’s product, service, or result can be profitable, what the profit margin may be, what the financial risk exposure may be, and what the true costs of the project may be. Some projects can generate profit directly. A construction company running a project to build a new strip mall will hopefully net a profit when the project is done. The investment firm, say, who hired the contractor to build the strip mall as part of a larger development project will not see a profit until leasing operations start generating income.

Examining the Project Life Cycle

By now, you’re more than familiar with the concept of a project life cycle. You also know that each project is different and that some attributes are common across all project life cycles. For example, the concept of breaking the project apart into manageable phases to move toward completion is typical across most projects.

As we’ve discussed, at the completion of a project phase, an inspection or audit is usually completed. This inspection confirms that the project is in alignment with the requirements and expectations of the customer. If the results of the audit or inspection are not in alignment, rework can happen, new expectations may be formulated, or the project may be killed.

Exploring Different Project Life Cycles

As more and more projects are technology-centric, it makes perfect sense for the PMBOK Guide to acknowledge the life cycles that exist within technology projects. Even if you don’t work in a technology project, it behooves you to understand the terminology associated with these different life cycles for the PMP examination. You should know about five technology-based life cycles:

![]() Predictive life cycles

Predictive life cycles

![]() Iterative life cycles

Iterative life cycles

![]() Incremental life cycles

Incremental life cycles

![]() Adaptive life cycles

Adaptive life cycles

![]() Hybrid life cycles

Hybrid life cycles

Predictive Life Cycles The predictive approach requires the project scope, the project time, and project costs to be defined early in the project timeline. Predictive life cycles have predefined phases, in which each phase completes a specific type of work and usually overlaps other phases in the project. You might also see predictive life cycles described as plan-driven or waterfall methodologies, because the project phases “cascade” into the subsequent phases and the Gantt chart looks like a waterfall.

Iterative Life Cycles This approach requires that the project scope be defined at a high level at the beginning of the project, but the costs and schedules are developed through iterations of planning as the project deliverable is more fully understood. The project moves through iterations of planning and definition based on discoveries during the project execution. The project team focuses on iterations of deliverables that can be released while continuing to develop and create the final project deliverable.

Incremental Life Cycles Incremental life cycles create the final product deliverable through a series of increment. Each increment of the project will add more and more functionality. Like the iterative life cycle, increments are a predetermined set amount of time, such as two or four weeks, for example. Before each increment, the team and a specific stakeholder determine what can be created within each increment, and then the increments begins and the team tackles the defined objectives. The project is done when the final increment creates a deliverable with sufficient capability as determined by the stakeholders.

Adaptive Life Cycles Adaptive life cycles are either agile, iterative, or incremental. Adaptive life cycles follow a defined methodology such as Scrum or eXtreme Programming (XP). Change is highly probable, and the project team will be working closely with the project stakeholders. You might also know this approach as agile or change-driven, because the team must be able to move or change quickly and the project scope and requirements are likely to change throughout the project. This approach also includes iterations of project work, but the iterations are fast sessions of planning and execution that usually last about two weeks. At the start of each phase, or iteration, of project work, the project manager, project team, and stakeholders will determine what requirements will be worked on next, based on the set of project requirements and what has been completed in the project.

Hybrid Life Cycles The hybrid life cycle is a combination of predictive and adaptive life cycles. Parts of the project can follow the predictive life cycle, such as project requirements and the budget, yet still utilize the flexibility and iterations that the adaptive life cycle offers. Hybrid life cycles can be, well, a bit messy, because there may be debates over what’s established and what’s being flexible. The project team and the project manager need a clear understanding of the “must haves” in the project and what components provide flexibility.

See the video “Project Life Cycle.”

Working Through a Project Life Cycle

Most projects phases move the project along. They allow a project manager to answer the following questions about the project:

![]() What work will be completed in each phase of the project?

What work will be completed in each phase of the project?

![]() What resources, people, equipment, and facilities will be needed within each phase?

What resources, people, equipment, and facilities will be needed within each phase?

![]() What are the expected deliverables of each phase?

What are the expected deliverables of each phase?

![]() What is the expected cost to complete a project phase?

What is the expected cost to complete a project phase?

![]() Which phases pose the highest amount of risk?

Which phases pose the highest amount of risk?

![]() What must be true in order for the phase to be considered complete?

What must be true in order for the phase to be considered complete?

Armed with the appropriate information for each project phase, the project manager can plan for cost, schedules, resource availability, risk management, and other project management activities to ensure that the project progresses successfully.

Although projects differ, other traits are common from project to project. Here are a few examples:

![]() Phases are generally sequential, as the completion of one phase enables the next phase to begin.

Phases are generally sequential, as the completion of one phase enables the next phase to begin.

![]() Cost and resource requirements are lower at the beginning of a project but grow as the project progresses. In a project, the bulk of the budget and the most resources are used during the executing process. Once the project moves into the final closing process, costs and resource requirements taper off dramatically.

Cost and resource requirements are lower at the beginning of a project but grow as the project progresses. In a project, the bulk of the budget and the most resources are used during the executing process. Once the project moves into the final closing process, costs and resource requirements taper off dramatically.

![]() Projects fail at the beginning, not at the end. In other words, the odds of completing are low at launch and high near completion. This means that decisions made at the beginning of a project live with the project throughout its life cycle, and a poor decision in the early phases can cause failure in the later phases.

Projects fail at the beginning, not at the end. In other words, the odds of completing are low at launch and high near completion. This means that decisions made at the beginning of a project live with the project throughout its life cycle, and a poor decision in the early phases can cause failure in the later phases.

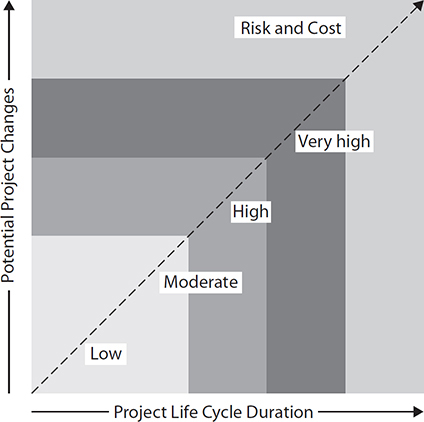

![]() The further the project is from completing, the higher the risk and uncertainty. Risk and uncertainty decrease as the project moves closer to fulfilling the project scope.

The further the project is from completing, the higher the risk and uncertainty. Risk and uncertainty decrease as the project moves closer to fulfilling the project scope.

![]() Changes are easier and more likely at the early phases of the project life cycle than near completion. Stakeholders can have a greater influence on the outcome of the project deliverables in the early phases, but in the final phases of the project life cycle, their influence on change diminishes. Thankfully, changes at the beginning of the project generally cost less and have lower risk than changes at the end of a project.

Changes are easier and more likely at the early phases of the project life cycle than near completion. Stakeholders can have a greater influence on the outcome of the project deliverables in the early phases, but in the final phases of the project life cycle, their influence on change diminishes. Thankfully, changes at the beginning of the project generally cost less and have lower risk than changes at the end of a project.

Your projects probably already follow a phasing structure that’s unique to the development, construction, or industry that you’re involved in. Typical phases of a project can include the following:

![]() Concept

Concept

![]() Feasibility study creation

Feasibility study creation

![]() Requirements gathering

Requirements gathering

![]() Solution development

Solution development

![]() Design and prototype creation

Design and prototype creation

![]() Build or execution

Build or execution

![]() Testing

Testing

![]() Operational transfer or transition

Operational transfer or transition

![]() Commissioning

Commissioning

![]() Reviewing

Reviewing

![]() Lessons learned documentation

Lessons learned documentation

Project Life Cycle vs. Product Life Cycle

There is some distinction between the project life cycle and the product life cycle. We’ve covered the project life cycle, the accumulation of phases from start to completion within a project, but what is a product life cycle?

In a project delivering products, a product life cycle is the parent of projects. Consider a company that wants to sell a new type of lemon soft drink. One of the projects the company may undertake to sell its new lemon soft drink is to create television commercials showing how tasty the beverage is. The creation of the television commercial may be considered one project in support of the product creation.

Many other projects may fall under the creation of the lemon soft drink: research, creation and testing, packaging, and more. Each project, however, needs to support the ultimate product: the tasty lemon soft drink. The product life cycle, though, also includes the ongoing operations of manufacturing, marketing, selling, distributing, and potentially end-of-life decommissioning of the product. Decommissioning of the product may involve a series of projects, but the other items are not projects—they are operations. Thus, the product life cycle oversees the smaller projects within the process and operations.

As a general rule, the product life cycle is the cradle-to-grave ongoing work of the product. Projects affecting the product are just blips on the radar screen of the whole product life cycle. Consider all of the projects that may happen to a home. The home is the product, while all the projects are things that make the product better or that sustain the existing product.

The Project Life Cycle in Action

Suppose you’re the project manager for HollyWorks Productions. Your company would like to create a new video camera that allows consumers to make video productions that can be transferred to different media types, such as VHS, DVD, and PCs. The video camera must be small, light, and affordable. This project life cycle has several phases from concept to completion (see Figure 1-3). Remember that the project life cycle is unique to each project, so don’t assume the phases within this sample will automatically map to any project you may be undertaking.

FIGURE 1-3 The project life cycle for Project HollyWorks

1. Proof-of-concept In this phase, you’ll work with business analysts, electrical engineers, customers, and manufacturing experts to confirm that such a camera is feasible to make. You’ll examine the projected costs and resources required to make the camera. If things go well, management may even front you some cash to build a prototype.

2. First build Management loves the positive information you’ve discovered in the proof-of-concept phase—they’ve set a budget for your project to continue into development. Now you’ll lead your project team through the process of designing and building a video camera according to the specifications from the stakeholders and management. Once the camera is built, your team will test, document, and adjust your camera for usability and feature-support.

3. Prototype manufacturing Things are going remarkably well with your video camera project. The project stakeholders loved the first build and have made some refinements to the design. Your project team builds a working model, thereby moving into prototyping the video camera’s manufacture and testing its cost-effectiveness and ease of mass production. The vision of the project is becoming a reality.

4. Final build The prototype of the camera went fairly well. The project team has documented flaws, and adjustments are being made. The project team is also working with the manufacturer to complete the requirements for materials and packaging. The project is nearing completion.

5. Operational transfer The project is complete. Your team has successfully designed, built, and moved into production a wonderful, affordable video camera. Each phase of the project allowed the camera to move toward completion. As the project came closer and closer to moving into operations, risk and project fluctuation waned.

Project Phase Deliverables

Every phase has deliverables. It’s one of the main points to having phases. For example, your manager gives you an unwieldy project that will require four years to complete and has a hefty budget of $16 million. Do you think management is going to say, “Have fun—see you in four years”?

Oh, if only they would, right?