CHAPTER 28

Dealing With Power and Politics in Project Management

Project management is more than techniques to complete projects on time, scope, and budget. Organizations by their very nature are political, so effective project managers need to become politically sensitive. Astute “project politicians” assess the environment and develop an effective political plan help to address the power structure in an organization. They identify critical stakeholders’ levels of impact and support, develop a guiding coalition, and determine areas of focus.

Because all projects involve change, project managers and team members find themselves involved in an organizational change process. To be ignorant about leading change can be costly to the organization and the individual. Instead of lamenting about a failed project, program, or initiative, it is possible to learn a proven approach to power, politics, and change that optimizes project success. Let’s examine some specific steps that make a difference between success and failure in a political environment.

It takes wisdom and courage to engage in action and change an approach to project work. Instead of facing unknowns, resistance and chaos alone, prepare for a hero’s journey. The approach shared below can help turn potential victim scenarios into win-win political victories.

Sooner or later all professionals find a leadership role thrust upon them, a team to lead, or a project to accomplish with others. Greater success comes to those who define, develop, and/or refine a plan to be successful. These people ultimately embrace the journey or process of changing an organization to be more efficient and more profitable by developing an organization-wide project management system, often called enterprise project management. Wise persons choose a proactive path, employing a change management process, replete with requisite political skills, rather than wishing they had done so in retrospect.

The path includes many uncertainties. Luckily, modern project management provides effective strategies to reduce uncertainties throughout the project life cycle. Opportunity comes to those leaders who understand and meld scope management and change management processes with skills in selling, negotiating, and politicking.

A common theme for success or failure of any organizational initiative is building a guiding coalition—a bonding of sponsors and influential people who support the change. This support, or not, represents a powerful force either toward or away from the goal. Gaining support means the difference between pushing on, modifying the approach, or exiting a path toward a new order of business. Moderate success may be achieved without widespread political support, but continuing long-term business impact requires alignment of power factors within the organization. Along the way, adapt effective concepts from nature to make organizations more project-friendly, which in turn leads to greater value-added, economically viable results.

Organizations attempting projects across functions, businesses and geographies increasingly encounter complexities that threaten their success. A common response is to set up control systems that inhibit the very results intended. This happens when we inhibit free flow of information and impose unnecessary constraints.

By contrast, taming the chaos and managing complexity are possible when stakeholders establish a strong sense of purpose, develop shared vision and values, and adopt patterns from nature that promote cooperation across cultural boundaries. These processes represent major change for many organizations.

An organic approach to project management acknowledges that people work best in an environment that supports their innate talents, strengths, and desires to contribute. Many organizational environments thwart rather than support these powerful forces in their drive to complete projects on time, on budget, and according to specifications. Applying lessons from complexity science offers a different approach—one that seeks to tame the chaos rather than implement onerous controls. A key is to look for behavioral patterns and incentives that naturally guide people toward a desired result. Results are similar to those of a successful gardener: combining the right conditions with the right ingredients creates a bountiful harvest. By ensuring that leadership, learning, means, and motivation are all present in appropriate amounts, the right people can employ efficient processes in an effective environment.

Too late, people often learn the power of a nonguiding coalition. This happens when a surprise attack results in a resource getting pulled, a project manager is reassigned, or a project is cancelled. Getting explicit commitments up front, the more public the better, is important to implementing any change. It also takes follow through to maintain the commitment. But if commitment was not obtained initially, it is not possible to maintain throughout. It all starts by investigating attitudes and assessing how things get done.1

VIEWS OF POLITICS

Albert Einstein said “Politics is more difficult than physics.” Politics will be present anytime an attempt is made to turn a vision for change into reality. It is a fact of life, not a dirty word that should be stamped out. A common view is what happens with negative politics, which is a win-lose environment in an underhanded or without-your-knowledge-of-what’s-happening approach. People feel manipulated, and the outcome is not desirable from their point of view. Secret discussions are more prevalent than public ones. Reciprocal agreements are made to benefit individuals rather than organizations.

The challenge is to create an environment for positive politics. That is, people operate with a win-win attitude. All actions are out in the open. People demonstratively work hard toward the common good. Outcomes are desirable or at least acceptable to all parties concerned. This is the view of power and politics being espoused in this writing.

One’s attitude toward political behavior becomes extremely important. Options are to be naive, be a shark that uses aggressive manipulation to reach the top, or to be politically sensible. According to Jeffrey Pinto, “politically sensible individuals enter organizations with few illusions about how many decisions are made.” They understand, either intuitively or through their own experience and mistakes, that politics is a facet of behavior that happens in all organizations. People who are politically sensitive neither shun nor embrace predatory politics. “Politically sensible individuals use politics as a way of making contacts, cutting deals, and gaining power and resources for their departments or projects to further corporate, rather than entirely personal, ends.2

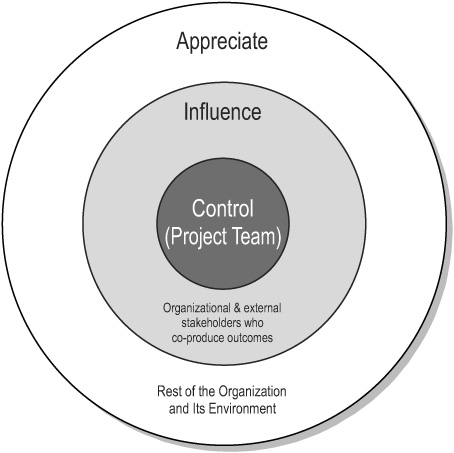

To make politics work for you, it is important to understand the levels of power in leading a project. As depicted in Figure 28-1:

• Control or authority power is the one most prevalent but not one that project managers can rely on with any degree of certainty in most organizations.

• Influence or status depends upon referent (or appealing to others) powers:

• Willingness to challenge the status quo.

• Create and communicate a vision.

• Empower others.

• Model desired behavior.

• Encourage others..

• Appreciation means having awareness of areas of uncertainty outside the realm of control or influence that could nevertheless impact project success. For instance, I cannot know when an upper manager will dictate a change in the project or a system will crash, but I can appreciate that these things happen and provide placeholders with contingencies for them in the project plan.

Politics are part of all organizations. Remarkably, power and politics are unpopular topics with many people. That ambivalent attitude hampers their ability to become skilled and effective.

Most organizations do not suffer from too much power; more so people feel there is too little power either being exercised to keep things moving or available to them. They often resort to a victim mode of feeling powerless. One high-level management team almost ceased to function when the general manager could not be present at the last moment for a critical meeting. The facilitator had to help them realize this was their opportunity to build a power base among themselves and to take action that presented a united front.

Lack of demonstrated power is also an opportunity to exercise personal power. Many people shine when they jump in and do something when they first see the opportunity, asking forgiveness later if necessary instead of waiting for permission.

FIGURE 28-1. TYPES OF STAKEHOLDER POWER

ASSESSING THE POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT

A big pitfall people fall into is not taking the time to fully assess what they are up against—learning how to operate effectively in a political environment.

What is a political environment? A negative reaction to the word “political” could be a barrier to success. Being political is not a bad thing when trying to get good things done for the organization. A political environment is the power structure, formal and informal. It is how things get done within the day-to-day processes as well as in a network of relationships. Power is the capacity each individual possesses to translate intention into reality and sustain it. Organizational politics is the exercise or use of power. The world of physics revolves around power. Because project management is all about getting results, it stands to reason that power is required. Political savvy is a vital ingredient for every project manager’s toolkit.

Understand the power structure in the organization. A view from outer space would not show the lines that separate countries, organizations or functional areas, or other political boundaries. The lines are figments that exist in our minds or on paper but not in reality. Clues to a power structure may come from an organizational chart, but how things get done goes far beyond that. Influence exists in people’s hearts and minds, where power derives more from legitimacy than from authority. Its presence is shown by the implementation of decisions.

Legitimacy is what people confer on their leaders. Being authentic and acting with integrity are factors a leader decides in relations to others, but legitimacy is the response from others. Position power may command respect, but ultimately how a leader behaves is what gains wholehearted commitment from followers. Legitimacy is the real prize, for it completes the circle. When people accept and legitimize the power of a leader, greater support gets directed toward the outcome; conversely, less resistance is present.

People have always used organizations to amplify human power. Art Kleiner states a premise that in every organization there is a core group of key people—the “people who really matter”—and the organization continually acts to fulfill the perceived needs and priorities of this group.3

Kleiner suggests numerous ways to determine who these powerful people are. People who have power are at the center of the organization’s informal network. They are symbolic representatives of the organization’s direction. They got this way because of their position, their rank, and their ability to hire and fire others. Maybe they control a key bottleneck or belong to a particular influential subculture. They may have personal charisma or integrity. These people take a visible stand on behalf of the organization’s principles and engender a level of mutual respect. They dedicate themselves as leaders to the organization’s ultimate best interests and set the organization’s direction. As they think or act or convey an attitude, so does the rest of the organization. Their characteristics and principles convey what an organization stands for. These are key people who, when open to change, can influence an organization to move in new directions or, when not open to change, keep it the same.

Another way to recognize key people is to look for decision makers in the mainstream business of the organization. They may be aligned with the headquarters culture, ethnic basis, or gender, speak the native language, or be part of the founding family. Some questions to ask about people in the organization are: Whose interests did we consider in making a decision? Who gets things done? Who could stop something from happening? Who are the “heroes?”

Power is not imposed by boundaries. Power is earned, not demanded. Power can come from position in the organization, what a person knows, a network of relationships, and possibly the situation, meaning a person could be placed in a situation that has a great deal of importance and focus in the organization.

A simple test for where power and influence reside is to observe who people talk to or go to with questions or for advice. Whose desk do people meet at? Who has a long string of voice or e-mail messages? Whose calendar is hard to get into?

One of the most reliable sources of power when working across organizations is the credibility a person builds through a network of relationships. It is necessary to have credibility before a person can attract team members, especially the best people, who are usually busy and have many other things competing for their time. Credibility comes from relationship building in a political environment.

In contrast, credibility gaps occur when previous experience did not fulfill expectations or when perceived abilities to perform are unknown and therefore questionable. Organizational memory has a lingering effect—people long remember what happened before and do not give up these perceptions without due cause. People more easily align with someone who has the power of knowledge credibility, but relationship credibility is something only each individual can build, or lose.

Power and politics also address the priority assigned to project management’s triple constraints—outcome, schedule, and cost. If the power in an organization resides in marketing where tradeshows rule new product introductions, meeting market window schedules becomes most important. An R&D driven organization tends to focus on features and new technology, often at the expense of schedule and cost.

POLITICAL PLAN

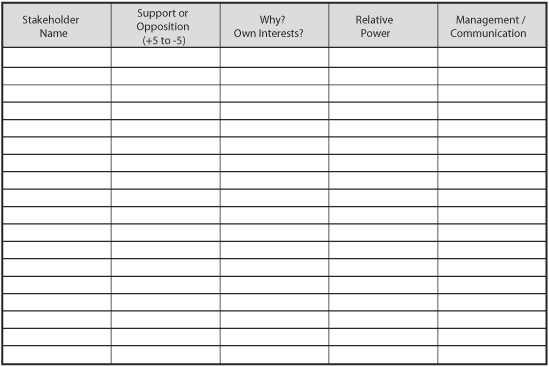

A quest to optimize results in a convoluted organizational environment requires a political management plan. This is probably a new addition to the project manager’s arsenal. Elements of a political plan may have been included in a communications plan. To conduct a systematic approach to power and politics, key element is to prepare a stakeholder analysis. One quickly realizes that it is impossible to satisfy everyone and that the goal might become to keep everyone minimally annoyed and to use a “weighted dissatisfaction” index.4

Stakeholder Analysis

Analysis of common success factors indicates that project leaders need to pay attention to the needs of project stakeholders as well as the needs of project team members. Identifying stakeholders early on leads to better stakeholder management throughout the project. Use the diagnostic tools and traits of key powerful people described previously to analyze stakeholders. A stakeholder is anyone who has a “stake in the ground” and cares about the effort—sponsoring the change, supplying, or executing it. Ask, “Who could stop this effort?” (See Figure 28-2 on pg. 382.)

To be thorough, visualize all stakeholders as points on a compass. To the north is the management chain; direct reports are to the south. To the west are customers and end users; other functional areas are to the east. In between are other entities, vendors, or regulatory agencies. Identify all players. Write down names and get to know people in each area. What motivates them, how are they measured, and what are their concerns?

Approach a stakeholder analysis using these steps:

1. Who are the stakeholders?

• Brainstorm to identify all possible stakeholders.

• Identify where each stakeholder is located.

• Identify the relationship the project team has with each stakeholder in terms of power and influence during the project life cycle.

2. What are stakeholder expectations?

• Identify primary high-level project expectations for each stakeholder.

3. How does the project or products affect stakeholders?

• Analyze how the products and deliverables affect each stakeholder.

• Determine what actions the stakeholder could take which would affect the success or failure of the project.

• Prioritize the stakeholders, based on who has the most positive or negative effect on project success or failure.

• Incorporate information from previous steps into a risk analysis plan to develop mitigation procedures for stakeholders who might negatively impact the project.

4. What information do stakeholders need?

• Identify from the information collected, what information needs to be furnished to each of them, when it should be provided, and how.

Prepare an action plan for using the stakeholder “map” to resolve political issues. That plan might include actions such as:

• Face to face meetings with each middle level manager, explaining the project mission and objectives, and getting them to share their real needs and expectations.

• Sessions with all middle managers, using “mind-mapping techniques” to brainstorm ideas and get suggestions and real needs from various perspectives, leading up to a more aligned vision for the project.

• Identifying and avoiding barriers like organizational climate, perceptions, customer pressure, and too many communication links.

Approach stakeholders in each area starting from the position of strength. When, for instance, power is high but agreement about the project is low, start by reinforcing the effective working relationship that exists and how the person may contribute to and benefit from the project. Express desire that this bond will help work through any differences. Only after establishing agreement on these objectives is it then appropriate to address the problem area. People often jump right into the problem. This prompts defensive behavior from the other person. Taking time to reestablish rapport first can prove far more effective to reach a mutually satisfying solution. It is then possible to discover misinformation or negotiate a change in outcome, cost, or schedule that lessens the levels of concern and moves people higher in supporting the project.

To illustrate, the customer says to the project manager, “I’m okay with most of your status report, but I have a big problem with progress on resolving the resourcing issue.” Most people only hear the problem and immediately jump into defensive mode. Instead, start with, “I hear that you’re satisfied with how we implemented your requests and can continue moving forward. Is that correct? Great! Okay, so now we only have this one issue to work through….” The tenor of this approach is positive, the topics on the table for discussion are bounded, and rapport is present, setting the mood for a creative solution.

Positioning

Another element of a political plan is positioning. For instance, where a project office is located in an organization affects its power base. The concept of “centrality” says to locate it in a position central and visible to other corporate members, where it is central to or important for organizational goals.5 HP’s Project Management Initiative started in Corporate Engineering, a good place to be because HP was an engineering company. That put the Initiative into the mainstream instead of in a peripheral organization where its effectiveness and exposure may be more limited. Likewise, a project office for the personal computer division reported through a section manager to the R&D functional manager. This again reflected centrality since R&D at that time drove product development efforts.

Most important decisions in organizations involve the allocation of scarce resources. Position and charter a project office with a key role in decision-making that is bound to the prioritization and distribution of organizational resources. Be there to help, not make decisions. Put managers at ease that they are not losing decision-making power but gaining an ally to facilitate and implement decisions.

An individual contributor, project leader, or project office of one needs to consider where he or she is located in an organization when wanting to have a greater impact, make a larger contribution, get promoted, or generally gain more power and influence. Doing service projects in a field office for a manufacturing and sales-oriented company is less likely to attract attention than a product marketing person doing new product introduction projects in the factory. Seek out projects that address critical factors facing the organization. In essence, address in a political plan how important the project is to the organization, where it resides in having access to key decision makers, and the support resources available to it.

Driving Change

Implicit in creating any new order is the notion that change is inevitable. The use of power and politics becomes a mechanism for driving change. Politics is a natural consequence of the interaction between organizational subsystems.

A well-known political tactic that enhances status is to demonstrate legitimacy and expertise. Developing proficiency and constantly employing new best practices around program and project management, combined with some of the above tactics in the political plan, plus communicating and promoting the services and successes achieved, helps a project gain status in the organization. This factor is a recurring theme in many case studies.

Pinto says, “Any action or change effort initiated by members of an organization that has the potential to alter the nature of current power relationships provides a tremendous impetus for political activity.”6

A business case can be made that changes are often necessary within organizations that set out to conquer new territory through projects and project teams, often guided by a project office. The role of upper managers may need to change in order to support these new efforts. However, it takes concerted effort, often on the part of project managers who are closest to the work, to speak the truth to upper managers who have the authority and power about what needs to happen.7 The change may be revolutionary and require specific skills and process steps to be effective. Change agents successfully navigate the political minefields by exercising these traits:

• Act from personal strengths, such as expert, visionary, or process owner.

• Develop a clear, convincing, and compelling message and make it visible to others.

• Use your passion that comes from deep values and beliefs about the work (if these are not present, then find a different program to work on).

• Be accountable for success of the organization, and ask others to do the same.

• Get explicit commitments from people to support the goals of the program so that they are more likely to follow through.

• Take action—first to articulate the needs, then help others understand the change, achieve small wins, and get the job done.

• Tap the energy that comes from the courage of your convictions … and from being prepared.

Conflict

Stakeholders’ competing interests are inherently in conflict. Upper managers and customers want more features, lower cost, less time, and more changes. Accountants mainly care about lower costs. Team members typically want fewer features to work on, more money, more time, and fewer changes. These voices ring out in cacophony. When people find that telling their problems to the project manager helps them get speedy resolution instead of recrimination, they feel like they have a true friend, one they cannot do without.

Conflict is natural and normal. Too little, however, and there is excessive force—“Whatever the group wants.” Too much, and there is excessive conviction—“My mind’s made up.” These represent the flight or fight extremes of human behavior. The ideal is to create constructive contention where the attitude is: “Let’s work together to figure this out.” This middle ground happens when:

• A common objective is present to which all parties can relate.

• People understand how they make a contribution.

• The issue under discussion has significance, both to the parties involved and to the organization.

• People are empowered to act on the issue and do not have to seek resolution elsewhere.

• Everyone accepts accountability for the success of the project or organizational venture.

For example, a material engineering manager was in a rage and called the taskforce project manager to ask how the project was proceeding. The project manager asked the other manager to come talk with him in person. Rather than putting up a defensive shield to ward off an upcoming attack, the project manager started the meeting by reviewing the project objectives and eliciting agreement that developing a process with consistent expectations and common terminology was a good thing. He next asked the materials manager about his concern and found out that inserting crosscheck steps early in the process would ensure that inventory overages would not happen when new products were designed with different parts. This represented a major contribution to the project. These individuals were empowered to make this change, which would have significant impact because all projects would be using the checklists generated by this project. Rather than creating a political battle, the two parties resolved the conflict through a simple process, the project achieved an improved outcome, and the two parties walked off arm in arm in the same direction.

Recognize that organizations are political. A commitment to positive politics is an essential attitude that creates a healthy, functional organization. Create relationships that are win-win (all parties gain), where actual intentions are out in the open (not hidden or distorted), and trust is the basis for ethical transactions. Determining what is important to others and providing value to recipients are currencies that project leaders can exchange with other people. Increased influence capacity comes from forming clear, convincing, and compelling arguments and communicating them through all appropriate means. Effective program managers embrace the notion that they are salespersons, politicians, and negotiators. Take the time to learn the skills of these professions and apply them daily.

Start any new initiative or change by thinking big but starting small. First implement a prototype and achieve a victory. Plan a strategy of small wins to develop credibility, feasibility, and to demonstrate value. Get increased support to expand based upon this solid foundation.

AUTHENTIC LEADERSHIP IN ACTION

Authenticity means that people believe what they say. Integrity means that they do what they say they will do, and for the reasons they stated. Authenticity and integrity link the head and the heart, the words and the action; they separate belief from disbelief and often make the difference between success and failure. Many people in organizations lament how their “leaders” lack authenticity and integrity. When that feeling is prevalent, trust cannot develop and optimal results are difficult if not impossible to achieve.

Integrity is the melding of ethics and values into action. Individuals who display this quality operate off a core set of beliefs that gain admiration from others. As a leader, integrity is critical for success. It is necessary if leaders wish to obtain wholehearted support from followers.

Integrity is the most difficult—and the most important—value a leader can demonstrate. Integrity is revealed slowly, day by day, in word and deed. Actions that compromise a leader’s integrity often have swift and profound repercussions. Every leader is in the “spotlight” of those they lead. As a result, shortcomings in integrity are readily apparent.

How do you create an environment that achieves results, trust, and learning instead of undermining them? One can observe many examples of “organizational perversities,” most often caused by leaders who are not authentic and who demonstrate lack of integrity. Demonstrating these values in action often makes the difference between success and failure. People generally will work anytime and follow anywhere a person who leads with authenticity and integrity.

It becomes painfully evident when team members sense discord between what they and their leaders believe is important. Energy levels drop, and productive work either ceases or slows down.

These managers display aspects of a common challenge—becoming a victim of the measurement and reward system. The axiom goes: “Show me how people are measured, and I’ll show you how they behave.” People have inner voices that reflect values and beliefs that lead to authenticity and integrity. They also experience external pressures to get results. The test for a true leader is to balance the internal with external pressures and to demonstrate truthfulness so that all concerned come to believe in the direction chosen. Measurement systems need to reflect authentically on the values and guiding principles of the organization. Forced or misguided metrics do more harm than good.

To get people working collaboratively in a political environment, consider ways for them to receive more value from this effort: the project provides means to meet organizational needs; they have more fun; the experience is stimulating; they get more help and assistance when needed; they get constructive feedback; they are excited by the vision; they learn more from this project; their professional needs are met; they travel and meet people; it’s good for their careers; together they’ll accomplish more than separately; this is neat….

Ways to demonstrate authentic leadership in action:

• Say what you believe.

• Act on what you say.

• Avoid “integrity crimes.”

• Involve team members in designing strategic implementation plans.

• Align values, projects, and organizational goals by asking questions, listening, and using an explicit process to link all actions to strategic goals.

• Foster an environment in which project teams can succeed by learning together and operating in a trusting, open organization.

• Develop the skill of “organizational awareness”—the ability to read the currents of emotions and political realities in groups. This is a competence vital to the behind-the-scenes networking and coalition building that allows individuals to wield influence, no matter what their professional role. Tap the energy that comes from acting upon the courage of convictions … from doing the right thing … and from being prepared.

For example, a contractor came to the project manager’s desk, made demands about resources on the project, and left. This was out of character, for the two people had formed a close relationship. The project manager decided not to act on the critical demands that could have severe negative impact on project relations. Later he sought out the contractor and found him in a different mood. The contractor confessed he was told by his company to make those demands. By correctly reading the emotional state and assessing that something below the surface was going on in that transaction, the project manager was able to work with the other person, keep the issue from escalating, and find a solution.

Leaders who commit “integrity crimes,” shift the burden away from a fundamental solution to their personal effectiveness. Trust cannot develop under these conditions. Leaders either get into problems or else tap the energy and loyalty of others to succeed.

In systems thinking terms, this is a classic example of a “shifting the burden” archetype, in which a short-term fix actually undermines a leader’s ability to take action at a more fundamental level. When under pressure for results, many project managers result to the “quick fix”—a command and control approach, which on a surface level appears to lessen the pressure. This has an opposite effect on the people they want to influence or persuade. These people do not do their best work so more pressure is felt to get results.

A more fundamental solution is to develop skills of persuasion as practiced by a change agent. Help people come to believe in the vision and mission and aid them to figure out why it is in their best interest to put their best work into the project. (Use Figure 28-2 to help analyze their interests and concerns.) People usually respond positively to this approach and accomplish the work with less pressure.

Tools of persuasion include:

• Reciprocity. Give an unsolicited gift. People will feel the need to give something back. Perhaps a big contract … or maybe just another opportunity to continue building a strong relationship.

• Consistency. Draw people into public commitments, even very small ones. This can be very effective in directing future action.

• Social Validation. Let people know that this approach is considered “the standard” by others. People often determine what they should do by looking at what others are doing.

• Liking. Let people know that we like them and that we are likeable too. People like to do business with people they like. Elements that build “liking” include physical attractiveness, similarity, compliments, and cooperation.

FIGURE 28-2. STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS TEMPLATE

• Authority. Be professional and personable in dress and demeanor. Other factors are experience, expertise, and scientific credentials.

• Scarcity. Remember just how rare good project management practice is, not to mention people who can transform a very culture. This applies to the value both of commodities and information. Not everyone knows what it takes to make a program successful.8

A summary of the science and practice of persuasion: It usually makes great sense to repay favors, behave consistently, follow the lead of similar others, favor the requests of those we like, heed legitimate authorities, and value scare resources.

To assess effective practices and apply a simple tool for analysis, consider these steps:

1. Identify basic leadership traits and their consequences.

2. Assess and compare leadership approaches in complex situations.

3. Apply a shifting-the-burden structure to create a positive culture.

4. Appreciate the value of authentic leadership and commit to act with integrity.

We’ve covered several techniques for political coalition building. The extent that powerful organizational forces are on board (or not) enables a project to go ahead in a big way, a project to be modified or downscaled, or for people to quit and move on to something easier.

A vision for project management is to become the standard management technique, operating in project-based organizations. Achieving this state requires forming a dream of what it would be like:

Project managers will be like current department managers. Upper managers will be an integral part of the project management process. The organizational building block will be the team. Therefore, upper managers will function as members of upper management teams. Project positions will be based on influence, which is based on trust and interdependence. Any one project will be part of a system of projects, not pitted against each other for resources but rather part of a coordinated plan to achieve organizational goals and strategy. This means project managers will themselves be a team. The upper manager’s team will develop the organization structure and lead the project system, or project portfolio. Trust will be supported by open and explicit communication. Upper managers will oversee a project management information system to answer questions and provide information on all projects. There will be less emphasis on rules but a strong emphasis on organizational mission to guide action. There will be clear relationships between individual jobs and the mission. A process for taming project chaos will be based on linking projects to strategy, a focus on values and direction, the free flow of information, and organizing to support project teams.

Between today’s situation and this desired state lies a long road of organizational change and the required politicking. Project managers who are skilled at the political arts of communication, persuasion, and negotiation—and who also are authentic and trustworthy—can help their organizations make this transition.

REFERENCES

1 Graham, Robert, and Randall Englund. Creating an Environment for Successful Projects: Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2004; Lewin, Roger, and Regine, Birute. The Soul at Work: Listen, Respond, Let Go; Embracing Complexity Science for Business Success. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000; and Pinto, Jeffrey K., Peg Thomas, Jeffrey Trailer, Todd Palmer, and Michele Govekar. Project Leadership. Newtown Square, Penn.: Project Management Institute, 1998.

2 Pinto, J. K. Power and Politics in Project Management. Upper Darby, Penn.: Project Management Institute, 1996.

3 Kleiner, Art. Who Really Matters: the Core Group Theory of Power, Privilege, and Success. New York: Currency Doubleday, 2003.

4 Pinto, “Power and Politics.”

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 See pp. 66–73 in Englund, Randall, Robert Graham, and Paul Dinsmore. Creating the Project Office: A Manager’s Guide to Leading Organizational Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2003 for a more thorough discussion about speaking truth to power.

8 Cialdini, R. B. Influence: Science and Practice (4th ed.). New York: Pearson Allyn & Bacon, 2000.