CHAPTER 19

Professionalization of Project Management: What Does It Mean for Practice?

As we move into the 21st century, work has become more knowledge oriented, and information workers in various occupations have recognized the similarity of their work to the traditional “professions” of the 20th century. Many of these occupations, led by teaching, nursing, and social work and including financial planners, surveyors, and many others, have embarked on professionalization initiatives seeking the recognition and privileges traditionally associated with medicine, law, accounting, engineering, and a very few other occupations.

In the last decade of the 20th century, project managers launched a similar professionalization mission. The Project Management Institute (PMI) stated that its mission is “to further the professionalization of project management” with the explicit intent of developing a new profession. Today, many project managers view project management as a “profession.” More than 65 percent of PMI’s membership explicitly recognizes project management as a profession.1

There is no question that these individuals conduct themselves in a professional manner when carrying out their responsibilities. Yet, there is equally no doubt that project management has not today attained the status of a traditional profession as defined in sociological terms, in which a profession is recognized as a special kind of occupation with a particular set of characteristics that carry with them a set of privileges and responsibilities. Professions are recognized by law in the Western world, and there are very few accepted in most Western jurisdictions.2

DEFINITION OF A PROFESSION

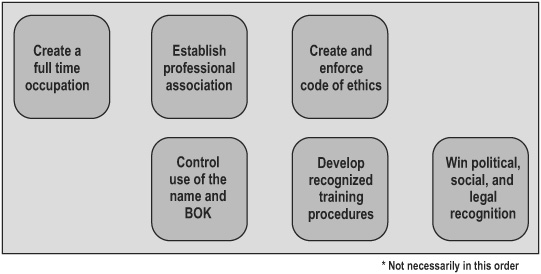

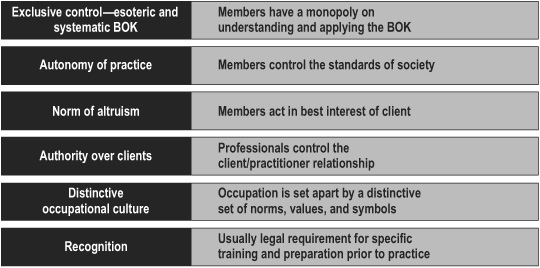

Professions have been studied in sociology for more than 75 years, when it was recognized that there existed a class of occupation that was typically accorded a higher degree of privilege and rewards than other occupations. Original studies of the professions focused on identifying the unique characteristics that distinguished professions from nonprofessions. This “trait approach” to professionalization typically identified the set of characteristics outlined in Figure 19-1 as fundamental to a profession.3, 4

These studies also identified the need to drive out malpractice and protect the public as a driving force in the legal recognition of the profession. The occupations of law, medicine, and lately engineering and accounting, typically formed the basis of study for research on the traditional professions.

According to trait theory, nursing, teaching, and social work (among others) are classified as “semiprofessions,” as they possess only some of the traits or have only partially developed some of the traits required by an occupation to be considered fully professional. Project management clearly fits into the “semiprofession” category5 as

explained below. Professionalization, or the path to professional status, requires consideration of both what a profession looks like (the traits) and the process by which these characteristics are attained. Figure 19-2 identifies the key activities usually associated with professionalization.

Abbott6 suggested that professions begin with the recognition by people that they are doing something that is not covered by other professions and the formation of a professional association. Forming a professional association defines a “competence territory” that members claim as their exclusive area of competent practice. The professionalization activity and its claims to professional status must be placed in historical, economic, political, and social context and seen as being fundamentally shaped by these conditions, rather than assuming that claims to professional status are objective, inevitable, and timeless. Claims to professional status (for example, “autonomy” or “esoteric knowledge”) are perceived as strategies in exerting occupational control and autonomy vis-à-vis other groups, including bureaucratic managers.7

FIGURE 19-1. TRAITS OF A PROFESSION

FIGURE 19-2. THE PROCESS OF PROFESSIONALIZATION

Understanding professionalization as a struggle between occupations to exert control and gain autonomy can provide superior insights into the historical struggle of occupations such as nursing, teaching, social work, and project management to achieve professional status. Indeed, some have pointed out that even the firmly established professions (such as medicine and law) are increasingly subject to broad social change questioning their traditional status, especially in the age of cutbacks.8,9 Thus, we turn to an examination of the status of project management in attaining the characteristics of a profession and then the requirements of professionalization through the processes and exercise of power with particular emphasis on what project management can learn from the struggles of other “semi-professions” and the actions of the various professional associations world wide to advance this initiative.

Status of Project Management

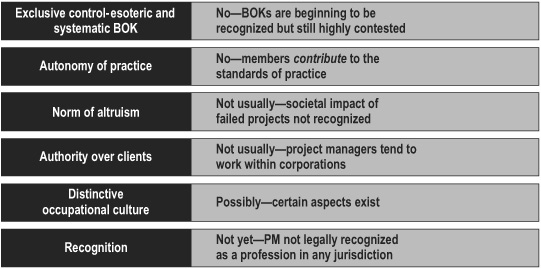

Figure 19-3 summarizes project management’s status in terms of developing the characteristics of a profession.

Clearly, project management has not yet achieved most of the characteristics of a traditional profession. Next we will look at the activities various project management bodies and practitioners have embarked on to achieve these characteristics.

THE PATH TO PROFESSIONALIZATION

The path to professionalization is composed of several lines of activity as introduced in Figure 19-3. Each of these activities is introduced below with reference to the actions of other emerging professions, and to the implications for project management in accomplishing this goal.

FIGURE 19-3. THE STATUS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Full-Time Occupation

Being recognized as a full-time occupation rather than a skill or technical tool required of a variety of occupations can be seen as the first step toward formal recognition of the “worth” of an occupation as separate from the other potential occupations within which this skill is practiced. An occupation has truly arrived in most Western jurisdictions when governments begin to collect occupational statistics. Until recently the only statistics available on the number of project managers worldwide came as estimates provided by PMI—no occupational statistics were available. Without being a recognized occupation, project management could never attain profession status and would always be seen as an attribute perhaps of some other profession (like architecture). About five years ago, we are told the U.S. government recognized project management as an occupation and would collect occupational statistics (though this has not been confirmed at press time). Thus, it appears that project management has been recognized as an occupation.

Monopoly Over Use of the Name

However, while the occupation has been recognized, there is still no clear definition of what a project manager is. To reach profession status, the term “project manager” must be captured and controlled. As long as anyone can use that designation without regard to training or certification, it will be impossible to create an occupation that can lay claim to “professional” status. To date, it appears that anyone will be able to self-report as a member of the project management occupation without reference to qualifications.

All analyses of “professionalization” processes include this criterion, but it should not be viewed in absolute terms. All claims to professionalization include a negotiated statement regarding what the practitioners include in their claims and what they leave out. Doctors don’t claim control or competency over everything in the domain of work in health. Teachers don’t claim the exclusive right to practice in all learning situations. Gaining control over the name will require defining which project management activities are to be the sole jurisdiction of professional project managers. What “projects” will “professional” project managers assume as theirs? and what will be left to anyone else who wants them? Where does the casual practitioner fit into the world of projects and where does the “professional” project manager enter? Not all projects are equal and not all projects require a professional. Currently, some of this activity is happening in individual organizations, as they create career ladders for project managers and define what qualifications are required for the use of the term within their organizational activities, and within some national jurisdictions in terms of competency rankings.

However, the protection of that designation or “name” will be ongoing, continuing part of the struggle between occupations, and between occupations and employers, to achieve control over the work. Through this ongoing process, the limits of the practice will be negotiated through time. Nurses do a number of things today that they did not do twenty years ago, as witnessed by the arrival of the Nurse Practitioner. This will require lobbying activities to win the right to that name and continuing efforts to police the use of the name. Conducted in a piecemeal fashion within various organizations and professional associations, this is likely to be a messy process.

Control Over the Body of Knowledge

The claim to “professional status” ultimately rests on the ability of the practitioners to lay claim to more or less exclusive command of an esoteric body of knowledge that they declare to be essential to good practice. The inability to make this claim convincingly is, perhaps, the primary factor responsible for the failure of teachers and social workers to achieve full recognition as “professionals.” Nurses, on the other hand, suffer not from the lack of a “hard scientific” body of knowledge, but rather from the fact that another group of professionals, physicians and surgeons, has laid claim to controlling that body of knowledge. Project management fits somewhere between these extremes.

The emergence of project management BOKs is a significant step in the right direction, but the development of a full-blown body of knowledge for project management will require a great deal of elaboration. In particular, professional bodies will have to be able to argue convincingly that the methods, ideas, and tools embedded in the project management BOKs and mastered by the professional project managers improves their ability to deliver projects and add value to clients. This is not a claim that can be substantiated by solid research evidence at this point in time—primarily because serious research on project management issues is still relatively rare.

Indeed, while the creation and maintenance of project management BOKs is a step in the right direction, so far there is no exclusive body of knowledge that holds the position of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles or recognized medical diagnostic tests in the world of project management doctrines. Project management guidelines are promulgated by other project management professional associations worldwide as well as those crafted by individual gurus and large companies. Without agreement on what this body of knowledge is and who is in charge of developing and maintaining it, professionalization will be difficult to achieve.

Education

Upgrading knowledge and developing recognized and ever more comprehensive educational programs has been a key aspect of professionalization in every case of a modern occupation striving to upgrade to “professional” status. The major established professions and the three semiprofessions of particular interest to project management—teaching, social work, and nursing10—all lay claim to their own faculty/college within the university higher education system. Accounting is the only profession that resides in someone else’s home (business or management faculty/colleges); the others all have their own deans. To date, project management has no clear home within the university setting. It is found in one of several locations, including business, engineering, or planning, and many universities provide no academic project management education, focusing only on providing project management training and professional certification preparation. Most training in project management still resides within corporate training, consulting, and professional organizations—entirely outside higher education. Development of a recognized academic discipline will be crucial to the professionalization project. While there will always be a demand for a wide array of educational offerings, the emergence of the academic discipline will entail negotiations between professional associations and academics.

Role of the Professional Associations

Professional associations in traditional professions are the center of control for the practitioners; they represent the interests of the practitioners to the outside world and enforces standards within the profession. A strong association mediates between public and private authorities on behalf of practitioners and directly influences the power and influence that accrues to that profession.

Today, a variety of local and global professional associations are alternately vying for recognition and authority in the project management world and cooperating to improve project management’s chances of becoming a 21st-century profession (see Crawford 2004a and b for more comprehensive discussions of these developments11,12). These and other important association initiatives are introduced below.

International Project Management Association (IPMA)

IPMA began as a community of practice for managers of international projects in 1965 but has evolved into a federation of approximately 40 national project management associations representing 50,000 members around the world (see IPMA Web site). The IPMA has developed its own standards and certification program, which is comprised of a central framework and quality assurance process plus national programs developed by association members. This association competes on a global basis with the programs of the Project Management Institute. However, recently the two organizations have been trying to find common ground for working together.

Project Management Institute

PMI began as the national project management association for the United States of America in 1969. Until the 1990s, this was a relatively small professional association. However, the 1990s witnessed exponential membership growth. By the late 1990s, PMI recognized that its membership of more than 100,000 was becoming international in nature. While PMI’s headquarters continues to be in Philadelphia and the organization continues to be subject to the laws of that state, in 2003 the first of three planned regional service centers was opened in Europe.

PMI’s large membership and global mandate suggests that it is the “leading nonprofit professional association in the area of project management” (http://www.pmi.org). However, it is still largely American in membership, nature, and approach (Crawford, 2004).

In addition to certification and registered education programs, PMI has instituted university accreditation programs. To date all of these programs are voluntary in nature. PMI has also initiated government lobbying both in North America and in emerging markets like China in recent years.

Regional Project Management Associations

There are almost 300 regional PMI chapters, national members of IPMA, or other national associations in the world today. A few are notable because of their size or activity in developing bodies of knowledge, standards, or certification programs. The Association for Project Management (APM) of the UK has a membership of 13,000 and has been actively involved in defining the project management body of knowledge over the years. The Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM) began in 1976 and operates independently of both PMI and IPMA. It has been a leader in encouraging the development of national project management associations in the Asia Pacific region. AIPM has also worked closely with the Australian government to develop national competency standards. Project Management South Africa is another independent professional association that has worked closely with their government to define performance-based competency standards. The Japan Project Management Forum is based on corporate rather than individual membership and has been actively involved in capability enhancement, the promotion of project management, and the development of a Japanese project management body of knowledge. The Project Management Research Committee of China has also been active in publishing the China National Competence Baseline.

Global Efforts

In addition, there have been efforts underway for the last decade to define a global approach to project management integrating the efforts of the independent associations and perhaps setting the foundations for a future global profession.

Certification/Licensing and Control

To attain professional status, professional associations must be given legal responsibility for designating who is qualified to practice. This may be very complicated, with a number of certification and licensing alternatives such as those found in medicine, or much simpler, as in the more generic licensing of teachers. If there is no effective certification and/or licensing scheme, then it will be impossible for practitioners to lay claim to any sort of special status or privileges. Certification is the key to control of the name and to control of admission to practice. In project management today, there are a number of largely voluntary certification approaches in project management ranging from knowledge-based assessment to competency standards based on practice.

In North America (and increasingly globally), PMI has a largely knowledge-based approach based on acquiring five years of project experience and then passing a test assessing knowledge of the concepts and terms included in their body of knowledge. Aggressive global growth over the last decade has given the Project Management Professional (PMP) designation widespread recognition and many organizations are using it as an entrance requirement when hiring project managers. In this way, the PMP certification is beginning to control entry into the practice of project management in many jurisdictions.

Other professional associations (for example, IPMA or AIPM) have more comprehensive certification processes that assess levels of project management knowledge and performance starting at the team member level and progressing up to project or program directors. All of these certification processes are largely voluntary, but in some countries (such as Africa or Australia), government involvement in certification has come close to providing legal recognition for certification.

AREAS OF CHALLENGE OR CONCERN

To date, no government has recognized the imperative to protect the public from the malpractice of individuals calling themselves project managers, even in the face of billion-dollar overruns on public projects. It is unlikely that governments will independently pursue actions to create a project management profession. In most jurisdictions, there is some question as to whether they even understand that there is a developed occupation of project management, despite the fact that individual organizations and associations establish standards and define programs for hiring and advancing project managers. It is also unlikely that private corporations will request or require the formation of a profession, as protecting their short-term interests is not likely to encompass creating this situation. Some may support the initiative, but many will resist in order to protect their autonomy and rights over the management of work.

For project management to become a “profession,” it requires the concerted effort of its practitioners and professional associations in pursuing this objective. Keys to achieving this status are as follows:

• Developing a defensible definition of project management that can be used to gain protection of the occupational name

• Developing a well-defined and complex body of knowledge that can be claimed by the profession and unequivocally asserted to create value

• Elaborating significant independent academic educational programs with an associated set of research programs

• Creating and enforcing a code of ethics for all practitioners using the title Project Manager

• Winning political, social, and legal recognition of the value of regulating project management for the good of society.

The most significant challenge facing the professionalization effort is gaining recognition and acceptance of the changes required of both professional associations and practitioners. Under a profession model, professional associations refocus from supporting the advancement and growth of practice in general to defining, regulating, and representing the collective “rights” of professional project managers. Practitioners at the same time need to decide whether they see project management as a profession that should be self-regulating and to which they are willing to submit their practice for judgment, or whether they would rather see it continue as an occupation subject to the whims of the market or even a tool kit of use in many occupations. These differences are significant in scope and have serious implications for development of either the occupation or profession.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS

Regardless of the potential for project management to achieve “professional” status, the promulgation of written standards, and the acceptance of these standards by important jurisdictions and organizations, has serious implications for the way a craft is practiced. Today, courts and other organizations can take these standards into account in defining negligent or competent practice. Some feel that it is only a matter of time before project managers are held legally accountable for the outcomes of projects. The Auditor General’s Office of Canada and many other organizations are attempting to use the ANSI standard PMBOK® Guide as a measure of project manager competence.

Clearly the professionalization effort has already created some serious implications for practitioners. Several of these are discussed below.

Bureaucratization of Practice

Practice standards and official guidelines in professional practice require that either practitioners follow the guidelines appropriately or justify why the particular context of activity required some other approach. Members of traditional professions maintain copious case notes and journals to enable them to reconstruct their professional reasoning if necessary. Professionals must be able to show that they followed established practice guidelines or justify why they did not. Many project managers operating in fast-paced environments may see this as unnecessary and time consuming when there is no clear evidence that the guidelines provide better results than other approaches.

In many ways, this bureaucratization of project management has led to complaints of increased “overhead costs” of project management at exactly the time practitioners are striving to streamline practice to increase the value added. Tradeoffs between following guidelines and getting things done in a timely fashion are already replete in project management discussions. Further professionalization without clear identification of when and where these guidelines need to be applied and when they can be shortcutted will exacerbate these conflicts. Interesting paradoxes are sure to arise.

Value of Certification

The value of certification is a hotly contested issue in project management. Many argue that the knowledge-based certifications that exist today simply show that you have some background knowledge and can pass an examination, not that you can successfully manage projects. Again, there is no clear evidence that certification increases the success of project managers on any clearly definable criteria.

In fact, certification and licensing are not designed to eliminate poor performance or to guarantee a very high standard in all cases. It has more to do with providing an adequate screening mechanism and controlling the entry of individuals into the profession. The value of licensing doctors came from eliminating thousands of quacks and incompetents and raising the general standard. As a consumer or patient, it is still up to you to find a “good” physician. The potential values arising through certification/licensing (professionalization) of project management are:

• Raising the general level of practice.

• Increasing the status of the practitioners.

• Increasing the rewards for practicing project managers.

• Screening out most of the individuals who should not be claiming that they are competent to practice.

However, most of these benefits come from setting the entrance criteria significantly high that not anyone who takes a course and studies can pass the exam. Failure rates on these “bar exams” are usually kept to a significant level. As the value of holding the certification rises, individual practitioners can expect the educational bar to be raised on attaining certification.

Benefits and Costs of Professionalization

The benefits of professionalization accrue to the majority of practitioners in terms of providing guidelines of practice, increased status, and recognition, but superstars often fail to see any benefit. Michael Jordan doesn’t need the players’ union, but most of the NBA players benefit from it. All professional project managers would benefit from increased status, pay, and authority in the project environment. However, many of the most successful practitioners probably already enjoy these benefits and are likely to oppose any constraints imposed on them. Those for whom managing projects has become an intuitive process of doing what is necessary will chafe against the need to document their decision processes. Expert project managers will be required to certify and abide by the laws of the professional association if they intend to continue practicing.

Professionalization also creates a legal liability to be assumed by practitioners. Costs of insurance and personal liability can be quite high, as evidenced by malpractice costs in medicine. The liability assumed by an uncertified, unlicensed worker is considerably less than that assumed by a registered, licensed member of a profession. The seal of the profession carries with it a personal liability associated with “bad” practice. A failed project managed by an ordinary employee does not carry the same possibility for the assumption of personal liability. In projects that go terribly wrong, these costs could be substantial.

Costs to projects and organizations also rise as requiring professional project management practice. These costs are usually seen in two particular areas. The first is in the cost of acquiring the services of a professional. The second is in the loss of control over organizational practices. Using a professional project manager requires recognizing the judgment of the project manager in many areas that were traditionally the responsibility of the organization’s management alone. Internal project management standards can only be applied as long as they adhere to the standards promulgated by the profession. Where there is a discrepancy, a professional project manager must go with the professional standard. Both of these can increase the costs of projects.

Costs to individual practitioners include the necessity to maintain current understanding of the body of knowledge and to continually update and upgrade skills. It will no longer be enough to master a body of knowledge and apply it as well as possible. It will now be necessary to ensure that your practice lives up to the evolving standards set by an outside body. Maintaining professional status becomes a cost and necessity of carrying out your professional practice. Certification will no longer be voluntary, and membership costs will usually rise to cover the increased costs of policing and developing the profession. Some form of insurance against malpractice is also likely to become a necessity.

Professionalization is often seen as a noble goal for emerging knowledge occupations. The activities of project management associations throughout the world reflect the growing efforts to attain this goal by achieving professional recognition. However, there remains much to be done to develop the characteristics and recognition of a traditional profession. Obtaining the status of a full profession will require significant effort from the members of an occupation to work together to achieve recognition. Gaining control over the characteristics of a profession requires both heavy initial investment and ongoing efforts directed at maintaining this status. Recognizing the benefits and costs of this type of initiative are a solid first step to developing the necessary commitment of practitioners to this lofty goal.

CONCLUSION

This chapter endeavors to provide practitioners with the background to clearly understand the issues involved in professionalization. From this foundation it is possible for individual practitioners to make informed choices about the activities they undertake to ensure their practice fits within this model and the implications of doing so. The process of initiating project managers into these practices will make a difference in how project management is understood and practiced in organizations.

REFERENCES

1 Project Management Institute. Project Management Factbook. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 1999.

2 Italy is a noted exception where many occupations, if not most, are recognized as professions with a legal mandate enforcing privileges and responsibilities of membership.

3 Roach Anleu, Sharyn L. The Professionalisation of Social Work? A Case Study of Three Organizational Settings. Sociology 26 (1992): 23–43.

4 Hugman, Richard. Organization and Professionalism: The Social Work Agenda in the 1990s. British Journal of Social Work 21 (1991): 199–216.

5 Zwerman, B., and Thomas, J. “Potential Barriers on the Road to Professionalization,” PM Network, Vol. 15 (2001): 50–62.

6 Abbott, Andrew. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

7 Aldridge, Meryl. Dragged to Market: Being a Profession in the Postmodern World. British Journal of Social Work, 26 (1996): 177–194.

8 Hugman, Richard. Professionalization in Social Work: The Challenge of Diversity. International Social Work 39 (1996): 131–147.

9 Labaree, David F. Power, Knowledge, and the Rationalization of Teaching: A Genealogy of the Movement to Professionalize Teaching, 62 (1992): 123–154.

9 Zwerman, B., Thomas, J., Haydt, S., and Williams, T. Professionalization of Project Management: Exploring the Past to Map the Future. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

10 Crawford, L. H. Global Body of Project Management Knowledge and Standards. In P. W. G. Morris, and J.K. Pinto (Editors), The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects (Vol. Chapter 46). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2004a.

11 Crawford, L. H. Professional Associations and Global Initiatives. In P. W. G. Morris, and J. K. Pinto (Editors), The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects (Vol. Chapter 56). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2004b.