CHAPTER 25

A Process of Organizational Change: From Bureaucracy to Project Management Orientation

Once upon a time … there was an organization that was attempting to change from a functional to a project management organization. The organization flourished in the bureaucratic mode with limited competition and stable products and services. However, it found itself in the intensive world of deregulated financial services. As more and more projects were developed to respond to the new environment, the company executives discovered that their project management practices were reflections of their bureaucratic past rather than of their project management future.

Attempts to teach managers the basics of project management were not successful. The newly-trained people found that the practices necessary for successful project management were not supported by the departments in the organization. From this experience, company executives came to realize that the organization needed to be changed in order to respond effectively to the new business environment. The process they followed in order to achieve that change is presented here as an example of the steps needed to install sound project management practices into a functional organization.

AN ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE MODEL

Research on organizational change indicates that most people in organizations will not change their behavior unless they see a clear need for such a change. Some people come to realize the need for change because their culture is not consistent with their business strategy. However, just realizing this does not bring it about. What is needed is a planned and directed organizational change effort that has the support and involvement of senior management.

The components of an organizational change effort are depicted in Figure 25-1. In general, they can be summarized as follows:

![]() Define new behavior. The senior managers must lead the move toward new behavior by clearly defining what the new behavior should be and what it should accomplish.

Define new behavior. The senior managers must lead the move toward new behavior by clearly defining what the new behavior should be and what it should accomplish.

![]() Teach new behavior. Once the new behavior is defined, it must be taught. This means that management development programs must be designed and developed to impart the knowledge as well as the feeling of what life will be like in the future organization. Senior managers must be a part of this program so that they understand the new behavior that is being taught. In addition, the program should incorporate feedback from participants to help refine what works in the organization.

Teach new behavior. Once the new behavior is defined, it must be taught. This means that management development programs must be designed and developed to impart the knowledge as well as the feeling of what life will be like in the future organization. Senior managers must be a part of this program so that they understand the new behavior that is being taught. In addition, the program should incorporate feedback from participants to help refine what works in the organization.

![]() Support new behavior. Development programs have little effect unless they are supported by senior management. In addition, there often needs to be a change in the reward system to ensure that the new behavior is rewarded and thus supported.

Support new behavior. Development programs have little effect unless they are supported by senior management. In addition, there often needs to be a change in the reward system to ensure that the new behavior is rewarded and thus supported.

FIGURE 25-1. COMPONENTS OF AN ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE EFFORT

![]() Model new behavior. Management development programs are reinforced by a combination of top management support and effective role models. This means that senior managers must exhibit the new behavior that is being taught and thus become effective role models for other organization members.1

Model new behavior. Management development programs are reinforced by a combination of top management support and effective role models. This means that senior managers must exhibit the new behavior that is being taught and thus become effective role models for other organization members.1

An organizational culture has been defined as “the environment of beliefs, customs, knowledge, practices, and conventionalized behavior of a particular social group.”2

So any change effort toward a project management culture must begin with a serious examination of the current beliefs and practices that caused projects to be less than successful. One way to achieve this is to compare successful and unsuccessful projects to determine what practices seemed to be present in the successful projects. This comparison could be augmented by practices that have been proven successful in other organizations. The result of this examination should be a description of the new, desired behavior.

Once this is determined, the new behavioral patterns must be taught. The lessons from the examination above should be put into a case study for use in the training program. At a minimum, the case study of the least successful project could become an indication of the types of assumptions and behavior that are not wanted.

AN ORGANIZATIONAL EXAMPLE

The organization described below—let’s call it OE (Organization Example)—is used to illustrate the types of problems typically encountered in attempts to change bureaucratic organizations. It is also used to illustrate how the change process described in the previous section can be applied for organizational change.

OE’s business began with a series of local offices selling consumer financial services. As the business grew, it became necessary to develop a general procedure manual so that all offices across the country would run according to the same principles and procedures. This manual was developed to such a degree that the placement of everything in the office was defined precisely such that any manager could walk into any office and know exactly where everything was. A highly structured organization grew up to support these procedures, and OE flourished as a result.

With such standardized procedures and with everyone going by the same book, it became part of the OE culture that people were interchangeable. That is, it was assumed—and it was true—that any manager could run any office. This assumption of interchangeable parts, such an asset in earlier years, later proved to be quite an obstacle to proper project management. The assumption led to the practice of continually moving people from project to project and changing the composition of the team as the project progressed. As this was common practice in the past, many managers failed to understand that in the project management world, people are not as interchangeable as they were in the past. Some of the general differences between a bureaucratic culture and a project management culture—which OE experienced—are summarized in Figure 25-2.

OE went through a tumultuous change as a result of the deregulation of the financial services market. Suddenly there were more competitors and fewer people on staff. This combination generated a sudden increase in the number of “special projects” in the organization. Most of these new projects involved computer technology, so that projects and project management became associated with the computer department. As there was little history of project management in the organization, it seemed natural that the project managers should come from the computer department. This assumption proved to be another obstacle to proper project management.

Project Management Culture |

|

Many standard procedures |

Few, new procedures |

Repeated processes and products |

New process and product |

More homogenous teams |

More heterogeneous teams |

Ongoing |

Limited life |

High staff level |

Low staff level |

High structure |

Low structure |

People more interchangeable |

People not interchangeable |

Little teamwork |

More teamwork and team building |

Positional authority |

Influence authority |

Departmental structure |

Matrix structure |

FIGURE 25-2. BUREAUCRATIC CULTURE VS. PROJECT MANAGEMENT CULTURE

The basic problem was that the person managing the project was not from the department that initiated the request. As such, the project manager had little formal responsibility and accountability other than making the product work technically. He or she had no formal responsibility to make certain that the product performed the way that the initiating department had envisioned.

“Accidental” project managers thus arose from the technical departments, and procedures evolved somewhat haphazardly. Each department involved mostly responded to requests from those project managers and were content to do only as requested. They did not share ownership of the final product. As the project manager was not ultimately responsible for achieving end results or benefits, the role evolved into one of project coordinator. As such, project success depended more on informal contacts, as there was little formal methodology. The role of project manager was highly ambiguous and thus not an envied position.

In addition, there was little concept of a continuing project team. People were often pulled onto a project as needed, and they were just as often pulled off a project in the middle of their work. As the project was identified with the computer department, contributing departments did not feel it necessary to keep people on a project for its duration. Thus, team membership was fluid, and there was often loss of continuity.

Despite all of these problems, there were some OE projects that were decidedly successful. However, there were others that were definitely unsuccessful. After a few of these failures, upper management decided that it was time for a change. This is the normal procedure with any decision about change. Any group will hold onto a set of procedures for as long as the procedures do not cause too many problems. One failure is usually not enough to change people’s minds. After a few failures, the need for change becomes clearer.

DEVELOPING THE NEW PROJECT MANAGEMENT CULTURE

Using the organizational change model in Figure 25-1, let’s examine the actions of OE executives as an example.

Step 1: Define New Behavior

To begin the change toward better project management, a conference of senior managers was arranged to examine what was right and what was wrong with project management practices at OE. At that conference the managers listed those projects that were deemed to be most—and least—successful. One division president became extremely interested when he realized that most of the failures were from his division. He became the champion for the management development program that was later developed.

From the analysis of the “winners and losers,” it became fairly clear what behavior patterns had to be modified. The senior management team then began the task of defining the new behavior, at least in outline form. Some of the changes in behavior defined were as follows:

![]() The project manager should be a defined role. The project manager should be designated from the user department and held accountable for the ultimate success of the project. It is up to the user department to define the specifications and see that they are delivered.

The project manager should be a defined role. The project manager should be designated from the user department and held accountable for the ultimate success of the project. It is up to the user department to define the specifications and see that they are delivered.

![]() A core team of people from the involved departments should be defined early on in the existence of major projects. The people on the core team should, if possible, stay on the team from the beginning until the end of the project. The project manager is responsible for developing, motivating, and managing the core team members to reach the ultimate success of the project.

A core team of people from the involved departments should be defined early on in the existence of major projects. The people on the core team should, if possible, stay on the team from the beginning until the end of the project. The project manager is responsible for developing, motivating, and managing the core team members to reach the ultimate success of the project.

![]() A joint project plan should be developed by the project manager and the core team members. This project plan should follow one of the several project-planning methodologies that were in use in the corporation. The specific methodology was not as important as the fact that the planning was indeed done.

A joint project plan should be developed by the project manager and the core team members. This project plan should follow one of the several project-planning methodologies that were in use in the corporation. The specific methodology was not as important as the fact that the planning was indeed done.

![]() A tracking system should be employed to help core team members understand deviations from the plan and then help them devise ways to revise that plan. The tracking system should also give good indications of current and future resource utilizations.

A tracking system should be employed to help core team members understand deviations from the plan and then help them devise ways to revise that plan. The tracking system should also give good indications of current and future resource utilizations.

![]() A postimplementation audit should be held to determine if the benefits of the project were indeed realized. In addition, the audit should provide a chance to learn lessons about project management so that projects could be better managed in the future.

A postimplementation audit should be held to determine if the benefits of the project were indeed realized. In addition, the audit should provide a chance to learn lessons about project management so that projects could be better managed in the future.

A case study was developed, based on a project failure, for use in the training program for the new project managers. It highlighted how things had gone wrong in the past and what behavior needed to be changed for the future.

Step 2: Teach New Behavior

Defining new behavior is not difficult; realizing the new behavior is quite a different matter. At this point the people from the management development area began to determine development needs. They began to ask the question of how to teach this new behavior throughout the organization.

In order to implement project management, the role of the project manager had to be redefined. In addition, people throughout the organization had to understand the new role of the project manager. This person was no longer to be just a coordinator, but a leader of a project team. This person had to do more than just worry about technical specifications, but rather, had to see to it that new changes were actually implemented. That is, the project manager had to lead a project team that would develop changes in the way that people in the organization did their business. Thus, the person also had to manage change.

These additional aspects redefined the role from that of project manager to that of project leader. The emphasis was then changed to developing a program on the role of project leadership. The program was aimed not only at the project leader, but also at the other people in the organization who had to appreciate the new role.

In addition to developing an appreciation of the new role, the development program also had to develop an appreciation of the use of influence skills rather than reliance on positional authority. In a bureaucratic culture there is a higher reliance on positional authority, but the increased responsibility of the project leader was not matched with increased authority. This is usually the norm in project management. Sometimes the project is identified with a powerful person so the project manager can reference that person and get referent authority. That is, the project manager can say, “The CEO wants this done,” and wield authority based on the CEO’s position. But in general, project leadership requires that the person develop his or her own abilities at influence and not depend so much on referent power. Therefore, the development program had to impart this idea in a usable form so the future project leaders would become more self-sufficient and more self-reliant, and would become entrepreneurs rather than simply project coordinators.

The project leadership role can be defined and put on paper, but it is not really meaningful until it is experienced. Thus, it was imperative that the training program be experiential, so that people could have a better idea of what the project leadership role would be like in the future. In addition, it was important that others on the project team, as well as others in the organization, experience what it would be like dealing with the new project leaders. It was thus decided that a simulation experience, involving all layers of management personnel, would be the best management development tool.

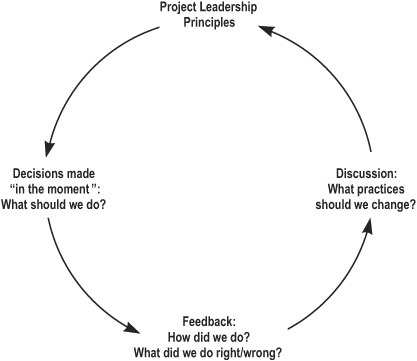

Using Simulation to Teach New Behavior

The simulation was a computer-based in-tray exercise where teams of people assume the role of project leader for a new software product. The simulation was used as a part of a learning process to put people “in the moment,” making decisions about project leadership. It is easy to teach the principles of leadership and project management, but when managers are “in the moment” of a decision, they often forget these new principles and rely on old patterns of behavior. The idea of the development program was to change those old behavior patterns, so the program was designed to first teach the new behavior and then put people in simulated situations where they learn to apply the new concepts. There is thus a large component of feedback in the simulation, which indicates if the simulation participants used old procedures rather than the new concepts. The simulation model is shown in Figure 25-3.

In the simulation, teams are presented with a variety of situations where they must solve problems that arise during the simulated project. Most of the problems have a behavioral orientation and deal with such areas as team building; obtaining and keeping resources; dealing with requests from clients, top management, and budgeting personnel; and generally living in a matrix organization. Each situation encountered has a limited number of offered solutions, and the team members must agree on one of the possible choices. During the normal play of the simulation, participants are scored on their ability to develop an effective project team and deliver a quality product while satisfying the often conflicting demands of top management, clients, accountants, and other important project stakeholders. The simulation presents situations that emphasize developing skills in the areas of building the project team, motivating the project team, managing diverse personalities on the project team, developing influence to achieve goals, developing a stakeholder strategy, and managing to be on time.

FIGURE 25-3. SIMULATION MODEL TO TEACH NEW BEHAVIOR

The simulation was used to give people some experience in a different world. It purposely did not simulate their current experience, as the idea was to get them ready for new organizational expectations. The simulation experience thus helped to clarify what the role of the project manager would be in the future and gave people some brief experience in this role. Potential project team members also received benefit as they experienced the problems of project management from the point of view of the project leader. They thus obtained a better understanding of what a project leader does and why they do what they do.

Step 3. Support New Behavior

Many organizational change efforts seem to die from a lack of senior management support. That is, people are trained to practice new behavior, they get excited about the benefits of the new behavior, but then they return to their departments and find that senior management still expects and rewards the old behavior. When this happens, the net effect of the management development program is to cause frustration. Thus, effective change strategies require constant interaction and communication between the training function and senior management to ensure that there is support for the behavior being learned.

The senior management at OE worked to ensure this communication and support. One of the division presidents sponsored the program and was physically present to introduce most courses and discuss why they were being offered. This sent a message to course participants that the move toward a project management culture was serious and supported by senior management.

The development program included a top management review of the perceived impediments to changing behavior in the organization. People in the development program often saw the benefits in changing behavior but sometimes felt that there were impediments in the organization, usually assumptions on the part of upper management that favored old behavior. Each group in the development program thus developed a list of those behaviors that they felt they could change themselves and those where they felt there were organizational impediments. These lists of impediments were then collected from the participants and presented to senior management. The senior management team then worked to remove the impediments and thus helped to support the change.

Step 4. Model New Behavior

Proper project management requires a discipline on the part of project leaders in the areas of planning, scheduling, and controlling the project, as well as dealing with the myriad of other problems that arise during the project execution. One aspect that senior managers may sometimes fail to realize is that it requires a similar discipline on their part. That is, in order effectively to ask subordinates to follow certain procedures, senior managers must be ready to follow those procedures themselves, or subordinates will not take the requested changes seriously. The process of instilling good project management into this organization thus began at the top. In effect, this means that senior managers must be role models for the changes that they want others to implement. This requires a number of behaviors on their part. Some of these are as follows:

![]() Enforce the role of project plans. Project management requires planning. However, if senior managers never review the plans, project leaders may not take planning seriously. In addition, project leaders should know how their project fits into the overall strategic plan for the organization. It is thus important that upper management work with the project leaders to review their project plans and show them where the project fits into the overall strategic plan.

Enforce the role of project plans. Project management requires planning. However, if senior managers never review the plans, project leaders may not take planning seriously. In addition, project leaders should know how their project fits into the overall strategic plan for the organization. It is thus important that upper management work with the project leaders to review their project plans and show them where the project fits into the overall strategic plan.

![]() Enforce the core team concept. Project management requires a core team of people that stays with the project from beginning to end. Most everyone in organizations believes that this is true, but adopting this approach limits senior managers’ ability to move people at will. Upper management must thus model the behavior of not moving people off core teams unless there is an extreme emergency. If they do not adopt this posture, the core team concept will fail.

Enforce the core team concept. Project management requires a core team of people that stays with the project from beginning to end. Most everyone in organizations believes that this is true, but adopting this approach limits senior managers’ ability to move people at will. Upper management must thus model the behavior of not moving people off core teams unless there is an extreme emergency. If they do not adopt this posture, the core team concept will fail.

![]() Empower the role of project leader. Project management requires that the end-user department take responsibility for the project. The project leader needs to be empowered from that user department. This means that the senior manager from the user department also takes responsibility for all projects in his or her department.

Empower the role of project leader. Project management requires that the end-user department take responsibility for the project. The project leader needs to be empowered from that user department. This means that the senior manager from the user department also takes responsibility for all projects in his or her department.

![]() Hold postimplementation audits. Project management requires that postimplementation audits be held to determine if the proposed benefits of the project were indeed realized. In addition, audits should be used to help members of the organization to develop better project management practices by reviewing past project experiences. The audit should be seen as a unique chance to learn from experience, and the results of audits should be reviewed by senior management.3

Hold postimplementation audits. Project management requires that postimplementation audits be held to determine if the proposed benefits of the project were indeed realized. In addition, audits should be used to help members of the organization to develop better project management practices by reviewing past project experiences. The audit should be seen as a unique chance to learn from experience, and the results of audits should be reviewed by senior management.3

How the Process Worked

We began with two programs for Executive Vice Presidents and Senior Vice Presidents. Every program consisted of three days of the simulation. Presenting a program for 25 participants every two months for four years, we had about 500 people exposed to correct project management practice. After the vice presidents were done, we started with the department directors, then on to the project managers themselves. After all of the project managers went through the program we started to train the actual team members.

Most of the programs were done at corporate headquarters. However, many of the problems originated in the credit card processing centers spread across the United States, so the program went on the road to the centers to ensure that they too were up on the new procedures. This had an amazing effect. First, they were learning the procedures just like everyone else. But more importantly, they were surprised that the people at headquarters were actually addressing the problems instead of just complaining about them. This made them eager to adopt the best practices.

At the end of each program, the PIP questionnaire on best practices was developed by Pinto and Slevin,4 which indicates how well the organization implemented best practices for project management. In every area, the people in this organization consistently scored in the 20th percentile or less. Those scores remained basically static for the first three years of the change process. Toward the end of the third year, we began to see many project team members who, after taking the simulation, would say, “Oh, that’s why they told us to do those things.” At this point, the scores jumped noticeably. Suddenly, this organization scored in about the 80th percentile on every best practice area. Best practices had finally taken hold in that organization.

LESSONS LEARNED

![]() Think long term. It takes a long time to install new procedures in an old organization. This process took about five years to complete in a mid-sized organization.

Think long term. It takes a long time to install new procedures in an old organization. This process took about five years to complete in a mid-sized organization.

![]() Start at the top. If you truly want the organization to change, you have to start at the top. This is particularly true of a hierarchical organization, like a bank, where all power and direction comes from the top.

Start at the top. If you truly want the organization to change, you have to start at the top. This is particularly true of a hierarchical organization, like a bank, where all power and direction comes from the top.

![]() Project management is for everyone. For project management to really take hold in organization, everyone in that organization must learn the procedures. Merely training the project managers in best procedures is not enough. New procedures must be learned and supported from the top of the organization all the way to the bottom.

Project management is for everyone. For project management to really take hold in organization, everyone in that organization must learn the procedures. Merely training the project managers in best procedures is not enough. New procedures must be learned and supported from the top of the organization all the way to the bottom.

![]() Measure your progress. Using a normed instrument like the PIP allows you to compare your organization to others, which helps to motivate program participants when they see how far they are behind others, while changes in these scores verify success of the change effort.

Measure your progress. Using a normed instrument like the PIP allows you to compare your organization to others, which helps to motivate program participants when they see how far they are behind others, while changes in these scores verify success of the change effort.

![]() Keep the faith. Progress does not appear in steady increments. Toward the end of three years, PIP scores remained low and it looked like we had nothing. Then, when we finally got down to the project team members, the scores suddenly jumped and everything jelled. This is a great example of the old parable of comparing change to turning water into ice. When cooling water all the way down to 33B0, it looks as if nothing much is happening. Then with one degree cooler to 32B0, the water suddenly turns to ice. This certainly happened at OE and would likely be similar in most other organizations.

Keep the faith. Progress does not appear in steady increments. Toward the end of three years, PIP scores remained low and it looked like we had nothing. Then, when we finally got down to the project team members, the scores suddenly jumped and everything jelled. This is a great example of the old parable of comparing change to turning water into ice. When cooling water all the way down to 33B0, it looks as if nothing much is happening. Then with one degree cooler to 32B0, the water suddenly turns to ice. This certainly happened at OE and would likely be similar in most other organizations.

REFERENCES

1 Graham, Robert J. Project Management as if People Mattered. Bala Cynwyd, PA: Primavera Press, 1989.

2 Cleland, David I. Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Tab Books, 1990: 352.

3 Graham, Robert and Randall Englund. Creating an Environment for Successful Projects: Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2004. See also Englund, Randall, Robert Graham and Paul Dinsmore. Creating the Project Office: a Manager’s Guide to Leading Organizational Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2003.

4 Pinto, Geoffrey, and Dennis Slevin. Project Success; Definition and Measurement Techniques. Project Management Journal, 19 (1988).