59

NANCY WHITE AND GABRIEL SHIRLEY

Online Environments That Support Change

A computer terminal is not some clunky old television with a typewriter in front of it. It is an interface where the mind and body can connect with the universe and move bits of it about.

—Douglas Adams

Washington State Public Health Nursing Directors

The Washington State Public Health Nursing Directors (PHND) are the state’s front line of public health communication, responsible for disseminating information and assisting in implementing public health policy for issues ranging from a West Nile Virus outbreak to possible chemical or biological attacks. They receive regulatory information from the federal and state levels and help regional health districts and hospitals develop policies, procedures, and readiness plans for public health emergencies. To be in a state of heightened preparedness is to live constantly on the leading edge of change. It’s a busy job.

The nursing directors meet face-to-face and via teleconference periodically to exchange information, ask questions, and discuss best practices. In the 1990s, they used an e-mail Listserv to help bridge the communication gaps between face-to-face meetings, to ask questions, and share useful practices from their day-to-day work. It was both a success and a failure.

Practices were shared by some and read by others, but there was no common space where the group’s wisdom was collected for future reference. They could communicate as a group instantly across hundreds of miles, engaging in their own time to accommodate busy schedules. Still, multiple simultaneous conversations created confusion, like ten people having ten different conversations all at once!

When the challenges of the e-mail list outweighed the benefits, the group looked for alternatives. They chose a Web-based discussion service providing multiple organized conversations, with different subgroups participating in each conversation. All conversations were accessible to anyone. “Flash conversations” (quick, easily started conversations) were created for a quick response to urgent issues.

When health districts share information, nurses, doctors, lawyers, and administrators save time. In autumn 2004, during a flu vaccine shortage in the United States, larger health districts used immunization clinics to vaccinate patients while using the situation as an emergency preparedness drill for a small pox epidemic. Smaller health districts did not have the resources to conduct the drill, but learned from their colleagues’ experience through the Online Environment.

Because PHND’s Web environment is private, their conversations sometimes include “venting sessions” about, for example, new policies from above. The online setting is a pressure release valve, providing a place to commiserate, as well as time for reflection and for carefully developing responses. As a result, face-to-face meetings are more productive and less emotionally charged.

The Basics

WHAT IS AN ONLINE ENVIRONMENT?

It is a technologically mediated “place” using the Internet to be together, to work, to share information, and to have conversations. It can be one tool, like e-mail, or many tools including discussion spaces, instant messaging, file sharing, and collaborative white boards. Anyone with Internet access can use Online Environments.

Online Environments are increasingly multimodal. Originally text based, today’s environments integrate audio, visuals (including video), and text, creating a rich communication medium. While some social gestures, such as body language, are lacking in some online environments, new gestures are emerging. Online presence indicators combine with other benefits, such as reflective space and centralized group memory, to create a rich environment. As technologies evolve, we naturally integrate online and off-line experiences into one coherent experience, utilizing the richness of all media.

At their best, Online Environments provide a platform to identify, connect, and engage diverse groups of people and information, creating the possibility of a new kind of collective action. They bridge time and distance, providing opportunities to discover useful questions, answers, and perspectives. Conversations emerge and stories are told. They offer transparency of both process and content, creating a record for reflection, study, and action. They provide a medium for accelerating and sustaining change.

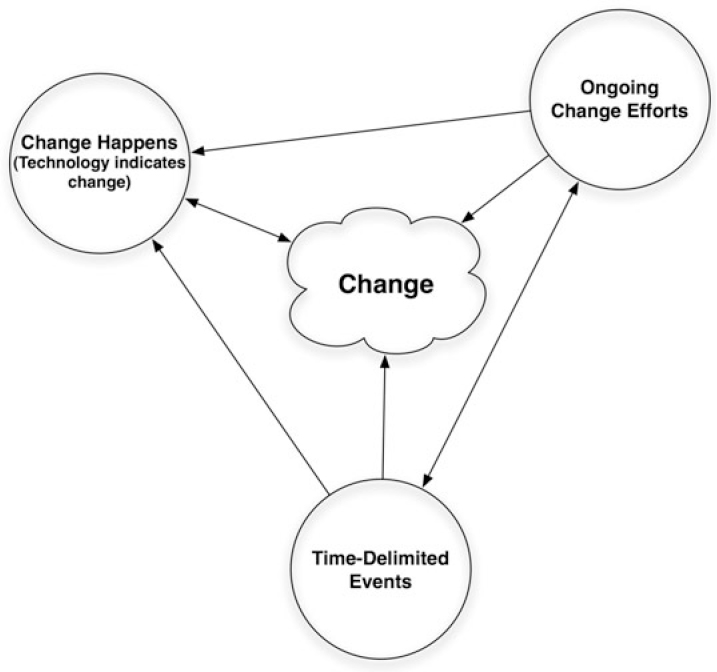

THREE PERSPECTIVES FOR CONSIDERING ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS FOR CHANGE

Why include online elements in change? How might they be of value? These “snapshots” reflect a continuum of potential uses. They can be mixed and remixed, and often overlap. Consider them an introduction to the many possibilities in a rapidly emerging domain. As you read them, think about the human interactions first and the technology second. Figure 1 illustrates the three perspectives.

Figure 1. Three Perspectives for Online Environments for Change

Supporting Time-Delimited Events

Online Environments can support change efforts that include significant events, such as an Open Space gathering or Appreciative Inquiry Summit, or they can be used for closing events and evaluation/reflection activities. Groups can be colocated or distributed.

Online Environments support events in several ways:

• Planning and Preparation: Dispersed Organizing Teams plan the event, recording key plans, interviews, research, action items, and assumptions in a centralized location open to all. As team members are added, they can review history or search it when questions arise. Transparency comes naturally, with all interactions captured in an “online record.”

• Registration and Logistics: Online registration can centrally gather logistical needs.

• Relationship Formation: Registration can end by inviting participants to a pre-event Web-based conversation to introduce oneself and learn about other participants. Members can share contact information, experiences, needs, and the like for use during the change process.

• Information Dissemination: Background materials provide an opportunity for participants to arrive with shared knowledge.

• Distributed Participation: Sometimes some people can’t join face-to-face events due to distance, cost, or schedule. Online Environments enable a variety of distributed participation strategies. Some “tune in live,” others extend the event over time for increased interaction and absorption.1

• Event Artifacts: Activities recorded in a variety of ways—audio, video, photographs, graphic recording, transcriptions, commitments, stories, notes, presentations, and so forth can be shared online for all participants to continue their work after the event ends.

• Extend Change Beyond the Original Event: Online Environments can be a place to share results, network with other change efforts, and create action plans, task forces, and work groups.

Supporting Ongoing Change Efforts

Change rarely happens in an instant, or in a single event. Online Environments can sustain the process from a variety of perspectives, some similar to the “event” perspective.

• Information Sharing: Collecting data, sharing documents, and posting schedules is quick and inexpensive with online tools.

• Ongoing Communication: “Talking” over time via online discussion tools, instant messengers, chat, and voice over IP (VOIP), allows conversations to continue among the entire group, or subsets working on aspects of the change initiative.

• Subgroups When Not Everyone Is Online: Sometimes only a portion of the people involved are, or need to be, online. A planning or leadership group may find Online Environments useful for coordination and process transparency.

• When the Change Connects to a Larger Network: Nothing exists in a vacuum. Often, organizations working on change interact with others in a larger system. Online Environments “show a face to the world” in an efficient manner, benefiting from the larger network’s knowledge. Doing some or all of a change effort “in public” online enhances access to those networks.

Change Happens: Technology as Influence on Existing Efforts and Practices

Change starts from a tiny spark, even a technological spark.

Using new technology sometimes (perhaps often) represents a social system’s implicit desire for change. Consciously, it may be “improving customer support” or “producing better widgets” or “creating better channels of communication between functional areas.” Someone gets a bright idea about helping the situation by using technology. “Wouldn’t it be great if the manufacturing team could see the design team’s work earlier in the process? Hey, we could set up a Web site and store designs in progress, inviting manufacturing folks to look and comment.”

In these situations, technology can change behavior and communication patterns, increase trust, agility, and productivity, without a formal “change effort.” It encourages existing conflicts to emerge when creative tension may benefit a process: “What are you guys doing?!! Don’t you know that doing it that way means reworking these other pieces? But if you do it this way …”

Technology shifts can provide fertile ground for pilot change projects, return on investment (ROI) studies, and early success stories. A few questions in a discovery session can uncover the story of change in progress: “What groups have implemented new technologies in the past two years? What motivated them? How has technology changed their behavior?”

New technology does not automatically imply that “change is happening.” There are many examples of technologies enforcing “the way things need to be.” Consider what motivated the change and its impact.

WHEN TO USE IT

Large-scale change methodologies construct a container for collective activity that can be supported, accelerated, and sustained using Online Environments … if the conditions are right. If the conditions aren’t good, the Online Environment may distract from the purpose. If you know more about change methods than technology, talk with others who can help bridge the gap.

Here are some starting points. Is it possible to do this change process entirely face-to-face? If so, how compelling is the motivation for adding an online component? How does it add value? Consider these questions, and if there are no compelling reasons, don’t go online!

LOGISTICAL REASONS

• Are participants separated by time or distance?

• Is there a need to create and nurture networks and communities over time and distance?

• Is there an event that would benefit from online support—before, during, or after?

• Are the cost or other factors of gathering face-to-face a barrier?

• Is the process going to last a long time where records, ongoing conversation, and information sharing will be useful?

• Will an Online Environment increase participation and access? Will it enable inclusion of more diverse voices than if there was no online option? Is this a desired outcome?

• Is there complexity that would be supported with a variety of interaction and recording options (i.e., are there needs for information exchange, conversation, relationship building, project tracking, and the sharing of artifacts like text, images, audio, and video)?

• Is there a need for transparency? Records of the interactions? How much transparency is useful?

• Are there special participant requirements that lend themselves to online interactions (communications needs, culture, etc.)?

• Are there people working in multiple languages or second languages that would benefit from “slowing down” the conversation to allow time for reflection?

MOTIVATION AND METHODOLOGY

• What motivates those who would use the technology? What are the demotivating forces?

• Is there a tangible and visible expansion of potential by going online?

• Will key stakeholders be willing to lead through action online?

• Will the motivation for connecting be stronger than the perceived barriers to using technology? This will be influenced by the technology used—so keep it as simple and intuitive as possible.

• Is there sufficient support and will to overcome technological and access barriers?

• Is there a need to support peripheral participation (people who “listen, read, watch” but may not be actively involved in the core processes)?

• Is there a need for privacy (suggesting boundaried, password-protected Online Environments)?

• How important is individual identity and personal voice versus collective identity and collective voice? (Identity evolves differently online.)

• Is increased transparency/visibility an opportunity or a threat?

PROBABLE OUTCOMES

Going online influences outcomes somewhat, but well-crafted interventions are about the change initiative, not the technology. Until people have experience and comfort with online tools, expect both interest in and resistance to technology. Beyond technological resistance, the transparency of the Online Environment highlights and even magnifies other types of resistance, including to change itself. This is one way Online Environments accelerate change. The joke is that our warts look even bigger online.

The environment can seem less warm and human to some, or so complicated that others feel disconnected. If you adopt Online Environments, helping people feel welcome and comfortable is critical.

If the initial group is successful, or transformed by its online experience, it influences future interactions. The change effort may reach other areas of the organization more quickly.

Successful online interactions can affect:

• Relationship Building: Broader “line of sight” and access to more people via online directories and interactions expands networks and deepens relationships.

• Knowledge Building: The old adage “two heads are better than one” is made visible by access to diverse knowledge and perspectives, building the overall group knowledge and enhancing group memory.

• Increased Transparency: Online records and open, traceable processes, where people see what is going on, support trust.

• Participation—Direct and Peripheral: Online Environments foster direct engagement and learning through observation.

• Flattened Hierarchy: Many-to-many access and communication means fewer layers of hierarchy are needed.

• Finding a Safe Space: Working out anxieties online can bring an enhanced quality of presence to face-to-face interactions.

• Heartbeat That Beats Beyond a Face-to-Face Meeting: The enormous energy of a face-to-face meeting creates a ripple effect that can be extended online.

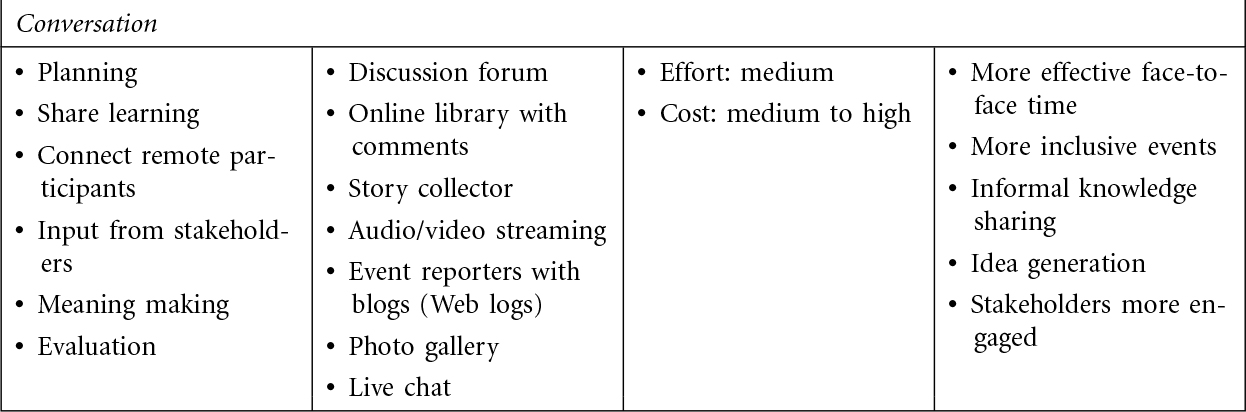

Table of Uses

Here are some common change activities and how Online Environments can support them:

Getting Started

Whether all online, or coupled with an existing off-line effort, the Online Environment is integral to the overall change effort. Here are nine interrelated elements to consider:

PURPOSE

Purpose drives everything. Be sure it is clear, understandable, and has clearly identified goals. Focus on change purpose first. NEVER adopt technology just because you can.

METHODOLOGY

Select a change methodology that fits your needs, preferences, and culture; then work on the technical or social architecture.

ACCESS

Assess the technological landscape—computers, internet connections, skill, and comfort of your audience—to determine what technologies to evaluate. Consider potential resistance to online approaches and cultural barriers that might be exacerbated online (i.e., beliefs about transparency, formality, etc.) to inform the design and implementation.

ARCHITECTURE: TECHNOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL

With purpose and methodology clear, access assured, design the technological and social architecture. These two interrelated strands evolve together.

Technological Architecture

Many change facilitators do not feel comfortable choosing and deploying technology. That’s okay. Do not use technology if you are strongly resistant. Put your energies elsewhere.

Selecting a suitable technical platform can be bewildering given the many options. An experienced partner who understands social systems, change efforts, and designing Online Environments helps.

Social Architecture

Once the technology is chosen, “prepare the space.” Online Environments for change generally begin with a minimal yet sufficient structure to orient participants. They “open the door” to possibilities, inviting participants to bring their thoughts, opinions, and issues. It is comfortable and feels immediately useful because issues people care about are discussed. Here are design decisions that help “open the door”:

• What’s public and what’s private? Make sure people know what can be “seen” by whom.

• Provide space for informal social interactions, especially for people who will not meet face-to-face. Discussion topics for introductions, social banter, and games help people get comfortable online.

• Create a compelling invitation. This is key to overcoming fear of technology or sense of “yet another thing” to do.

• Provide content and information. Making background information available increases comfort for some participants.

• Structure an “on-ramp” into the space. Start with minimum tools and content areas to prevent overwhelm, and add new areas as needed.

• Balance control and emergence. Structure provides a safe transition to the Online Environment. Choices support emergent needs and directions. Both are required, and balancing them is an art.

FACILITATION

Facilitation glues the other pieces together, bridging the gaps between process, technology, content, and experience. Plan time and activities for people to get comfortable. Help participants learn new tools and processes. Do a short telephone orientation and walk-through, answering questions and relating them to the purpose at hand.

Consider who will facilitate; with a global group, recruit from different time zones for broader coverage. Cofacilitators help discern meaning in a text world, checking with each other when not sure how to interpret a response.

ITERATION, ADJUSTMENT, AND EVALUATION

This framework has all the ingredients to start. One additional piece is particularly relevant online: Iteration. Online Environments and tools are fairly “plastic.” Tweak and adjust them in small, easy-to-tolerate increments. Solicit feedback, watch interaction patterns, and constantly improve the environment to serve your purpose (figure 2).

Figure 2. Be Prepared to Iterate and Evolve Over Time

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR THIS APPROACH

Online Environments reflect and amplify what is already present in a group, both positive and negative.

If groups are open to change, an Online Environment accelerates it by increasing the density of connections and flow of information/conversation among people.

The environment requires flexibility to grow and change with the participants’ changing needs. Flexible technology, flexible design, frequent redesign, agility to switch technologies quickly, or some combination of all of these is a must.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Relationships

SPONSORSHIP REQUIREMENTS

As in off-line efforts, sponsor commitment gives participants confidence that their efforts are recognized. Having sponsors who are open to supporting what emerges from the group’s activities is vital. Unique to the Online Environment, where interactions are recorded, is comfort with transparency. There is no place to hide!

Beyond the invitation, direct sponsor participation depends on the project. Their participation is often as a catalyst and role model. If they are technology shy, support their learning.

WHAT QUALITIES AND SKILLS MAKE A GOOD FACILITATOR?

Online facilitation3 encompasses face-to-face expertise, plus comfort and skill with technology. Often the facilitator supports the group processes, and serves as tech support and tool trainer. They often model online processes unfamiliar to a group, such as sociability in a foreign environment—“talking” with people they can’t “see.”

Competencies include:

• Modeling the basics of social interaction online—responding appreciatively, asking clarifying questions, commenting, and continuously inviting participants to share their hopes, ideas, and visions for the future.

• Modeling the use of the tools and processes.

• Providing or referring people to technical assistance.

• Weaving together conversations from different “spaces” online, or cross-linking them for greater visibility and synergy.

• Working with misunderstandings that happen more easily online.

PARTICIPANTS AND OTHER ROLES

The key role for participants is to show up and be present—bringing hopes, desires, ideas, and inspirations. Showing up takes visible and invisible forms—active engagement/posting or passive listening/reading. Both are valuable. Build trust explicitly online, as people often rely on face-to-face cues.

Participant expectations depend on the design and intention of the process. Generally showing up, introducing themselves, raising issues of importance, and engaging in topical conversations, decision-making processes, and ongoing team activity are involved.

Conditions for Success

WHEN YOU WOULD USE THIS APPROACH

From the convenience and speed of electronic communication to support for a complex initiative that spans space and time, solutions can be simple or elaborate. Think of throwing a party. Sometimes setting out the cheese and crackers is enough. Other times an elaborate table with a multicourse meal and paired wines is required. Context is everything.

WHY IT WORKS

Designing and executing based on the context is a condition for success. However, there is a caveat: Online Environments and interaction are still new. We don’t know all there is to know. Sometimes it doesn’t work. Do not use this method if there is no technology support. Be prepared to be surprised. Don’t use it when the purpose and value is less compelling than the barriers of using technology.

When it does work, there are a variety of reasons. It creates a “common now”—a space where time and experience is preserved for group interactions regardless of time zone. It provides opportunities to express divergent ideas simultaneously and converge them via collective processes. Reflective thinkers are often more comfortable online than face-to-face, feeling more engaged and valued. A common space for group activity forces the issue of organizing collective information for historical access. Search features provide a method to find gems that previously were lost forever.

Theoretical Basis

HISTORY OF CREATION

The history of Online Environments for change sits in the evolution of online communities,4 computer-supported communication, and distributed group work (teams). From early experiences of scientific and academic networks, Usenet, the early online e-mail, and Web-based online communities, to today’s sophisticated mix of tools and approaches, online interaction continues to grow in complexity and variety. It evolves on two complementary but not always congruent axes of technology development and process innovation. As more off-line change processes adopt technology, new combinations are emerging, including tools designed for specific processes. Through lessons learned from the early work of Peter and Trudy Johnson-Lenz (www.awakentech.com), Lisa Kimball (formerly of www.metanet.org, now www.groupjazz.com), and Doug Carmichael of www.metanet.org, to the recent work of WebLab (www.weblab.org) and AmericaSpeaks (www.americaspeaks.org), the landscape continues to change. New processes, springing out of the affordances of technology, promise yet more innovation.

CRITICAL UNDERLYING THEORY AROUND ONLINE COMMUNICATIONS

A large body of theory and research underpins online interaction technologies and practices for change efforts. It has spawned “Internet Research,” spanning many disciplines, from sociology and anthropology to the cognitive sciences. Two primary areas inform work in online interaction environments: computer-mediated communications research and online group research (virtual teams, online communities, online learning, and network theory).

SOCIAL INTERACTION ONLINE

For example, trust is formed and withdrawn differently online, influencing group interactions. Relationship formation follows different paths online, more easily forming “loose bonds” and more slowly forming tighter bonds and relationships.5 Identity—or more accurately, the small slices of identity we share online—affects our interactions.

The body of research is young, and early conclusions are situated in specific contexts that may not generalize to other online interactions. There are conflicting conclusions about the absence of face-to-face contact. Even a quick scan shows the need for more research. The studies are small and few track what happens in distributed groups mixing online and off-line or the role organizational culture plays.

EXPERIENCE

Individual learning and communication styles affect online experiences, particularly when working in only one modality, such as text. Those not comfortable reading on a screen, for example, are significantly disadvantaged. For aural learners, audio (podcasts, videos) enhances their experience. Knowledge of the different preferences is important in designing Online Environments. Virtual team research informs us about group experience, including processes for negotiating interdependent tasks in a change effort.

ATTENTION

The concept of “continual partial attention,” coined by Microsoft researcher Linda Stone,6 indicates that often we pay less attention to various electronic communication streams because we are paying attention to more than one at a time, or we are splitting our attention online and off-line. Think of listening to a phone call and reading e-mail or participating in an online meeting and a family member interrupts you. This partial attention can rob the end results of fullness. In contrast, electronic communication puts more in our line of sight, allowing new connections, insights, and innovation. New technologies for combining tools and content add opportunity and complexity. We don’t yet understand how this affects our attention.

Finally, research is blossoming around the sociopolitical aspects of online interaction, including the “digital divide.” This research examines complexities of who has access and control of online technologies, and how technology and its underlying values influence online interaction, coloring the application of Online Environments to change efforts.

Sustaining the Results

If your Online Environment begins with visioning, consider expanding it to accomplish daily work. Long-term and near-term work spaces within the same Online Environment can inform each other.

Alternatively, use an event model where the Online Environment is always available but is actively used periodically.

Another approach is archiving your Online Environment once it has accomplished its goals, keeping it available for reference. Officially closing an environment may reinforce positive experiences and a desire to “do it again one day.”

Burning Questions

Three types of burning questions are common:

1. Most frequent: “Isn’t online a poor second to face-to-face?” Online interactions can augment face-to-face and enable connections where face-to-face isn’t possible. Here is a reframe of the question: “Isn’t connecting and communicating around change essential—any way we might get it? How do we create the best possible Online Environments and interactions?”

2. More an assumption than a question: “Since it is online, it is free and fast, right?” It is rarely free and almost never fast. Human communication takes time and attention, regardless of the environment. Time is used differently online, complementing our personal schedules. But it still takes time. The cost can be far less than flying 30 people to a city and staying in a hotel for three days. Still, software, design, training, and facilitation have a cost.

3. Finally, the most challenging and ongoing question is how to get individuals and groups to participate. The emerging answers address the first question about “poor second” to face-to-face. When people have a meaningful online experience, the first question goes away. The challenge is designing and deploying online interactions that capture deep attention, meet real needs, and connect people with warm, electronic communications.

Some Final Comments/Possibilities for the Future

Online interaction environments are in their infancy. Our skills at successfully communicating and working within them are new. This is a rapidly evolving domain with new tools literally emerging daily, along with creative applications of human processes designed for online use.

Some technological developments like wikis (easy-to-create Web pages that can be edited by any user), blogs (Web logs), and communal resource sharing may support bottom-up self-organizing, unlocking doors. The emergent creative “hacking” of images from services like www.flickr.com may tap our visual interaction skills. Podcasting and vodcasting for easy online audio and video brings the warmth of voice and nuance of body language. Graphic facilitation, which has so enriched off-line facilitation, is beginning to blossom online. Some Web services even allow people to create and configure their own tools without knowing a computer language.

Imagine this: Nongovernmental disaster relief workers are facing a crisis. Scattered across the world, they mobilize with images, data, tools, and the critical conversations that quickly make meaning, chart a course of action, and respond. Geographic positioning systems track their work and provide critical feedback so that the system as a whole quickly adjusts as new patterns, resources, and scenarios emerge. Questions from the field flow to a “global brain bank” and are answered within minutes or hours, rather than days or weeks. Support surrounds an isolated relief worker through communication channels embedded in her mobile phone, which also translates in six languages so she works in context with those around her. And her partner, 3,000 miles away, gets to say “good night” every night … online.

These visions do not diminish the incredible warmth we share as humans who gather face-to-face. This is not an issue of “replacing warm communication with cold.” It is twofold: finding our warmth and humanity online, and identifying the mix of online and off-line, enabling people to achieve their goals and fulfill their potential. Embracing the mix of perspectives moves us forward in making wise choices in a world that needs all the wisdom it can get. No technology surpasses a hug, or a shared meal. Rather, it prepares us for finding still more connections that create change.

About the Authors

Gabriel Shirley ([email protected]) is an entrepreneur and consultant working at the convergence of leadership development, human potential, emergence, and technology. He has designed online collaboration technologies and consulted with start-ups, NGOs, and Fortune 50 companies to further their change efforts through the appropriate use of technology. He is the founder of BigMind Media, where he designed the BigMind Catalyst online platform and Big-Mind Consulting, where he currently works as an independent consultant. Gabriel’s personal change effort is to inspire people … to live their dreams, to be more productive than they knew was possible, and use business as an opportunity to improve the human condition. Online Environments are one medium he uses to accelerate that process.

Nancy White ([email protected]) is a leader in the field of online facilitation and online interaction design. She works in the nonprofit, organizational, and business spheres helping people connect and achieve their goals online and off-line. She has a particular interest in online collaboration and connection for people who would otherwise not be able to work together due to time, distance, and resources. She writes, teaches, and speaks about online interaction strategies and online facilitation, encouraging development of the practice in a wide range of settings. Nancy founded Full Circle Associates. She actively chronicles developments in online interaction through her blog (www.fullcirc.com/weblog/onfacblog.htm) and Web site (www.fullcirc.com).

Where to Go for More Information

REFERENCES

Barab, Sasha A., Rob Kling, and James H. Gray, eds. Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Lipnack, J., and J. Stamps. Virtual Teams: Reaching Across Space, Time, and Organizations with Technology. New York: John Wiley, 1997.

Rheingold, Howard. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1993.

Schuler, Doug. New Community Networks: Wired for Change. New York: ACM Press, 1996.

Smith, Mark, and Peter Kollock, eds. Communities in Cyberspace. New York: Routledge, 1999.

INFLUENTIAL SOURCES

Hock, Dee W. Birth of the Chaordic Age. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1999.

Mohr, Bernard, and Jane Magruder Watkins. Appreciative Inquiry—Change at the Speed of Imagination. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 2001.

Owen, Harrison. Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide, 2d ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1997.

Senge, Peter, Otto C. Sharmer, Joseph Jaworski, and Betty Sue Flowers. Presence: Exploring Profound Change in People, Organizations, and Society. New York: Doubleday, 2005.

Sheldrake, Rupert. The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Habits of Nature. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 1995.

ORGANIZATIONS

BigMind Consulting—www.bigmindconsulting.com

Full Circle Associates—www.fullcirc.com

OTHER RESOURCES

Methods for Change—http://methodsforchange.com

Nancy White’s Online Community Toolkit—www.fullcirc.com/community/communitymanual.htm

Open Space Institute (USA)—www.openspaceworld.org/cgi/wiki.cgi?OpenSpaceInstituteUSA Sample of a wiki.

1. Blending face-to-face and online is one of the more complex deployments. All virtual or all face-to-face is easier!

2. Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive & Computational Perspectives) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), http://emerge2004.net/osn_presentation/emerge2004_files/v3_document.htm.

3. For more, see www.fullcirc.com/community/facilitatorqualities.htm and www.fullcirc.com/community/onlinefacilitationbasics.html.

4. Howard Rheingold, The Virtual Community, www.rheingold.com/vc/book/.

5. M. Chayko, Connecting: How We Form Social Bonds and Communities in the Internet Age (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002).

6. Cited in Thomas Friedman, “Technology Backlash,” San Juan Star, January 31, 2001, p. 23.