60

SARAH HALLEY AND JONATHAN FOX

Playback Theatre

You try to cross over into that part of you that’s always there but is only alive when you’re playing.

—Dwike Mitchell

Sharing Personal Experience

Imagine a stage with two chairs off to one side, a combination of wooden boxes and simple colored fabrics center stage, and a variety of musical instruments on the other side. The occasion is a staff recognition dinner, with about 100 staff members from affiliated nursing homes and senior centers in the audience. The actors, conductor, and musician enter in a way that evokes the artistic and ritual feeling of a theatrical performance.

The performers begin as themselves, with a song, and an introduction that models the self-disclosure and public sharing that is a necessary component of Playback Theatre (figure 1). The conductor, who acts as a kind of master of ceremonies, sets the stage by welcoming the audience and saying a few words about what Playback Theatre is and what people might expect in the next hour or so. The conductor then begins to invite audience members to tell short moments, feelings, and experiences that are played back by the actors and musician. The process continues—the conductor asks questions, audience members respond, and then actors embody the story on stage.

The conductor invites longer stories in which the teller sits onstage next to the conductor for the interview and enactment. One person after another tells about how demanding the work is and how thin they are stretched. The actors act out the feelings. Then the conductor asks, “Why do you do the work you do?” A woman comes to the teller’s chair. She tells how she has grown up in the city, on a block where there were many older people. As a child, she had thought of them all as her grandparents. So it seemed natural for her to care for older adults as a profession. As the actors portray the teller as a young girl with her older neighbors, the love between them is palpable. There are many moist eyes in the audience. After the story, the atmosphere in the room changes. There is a sense of vision present and a feeling of renewal. The performance ends with reflection of the stories and themes present as integration.

Figure 1. What Playback Theatre Looks Like

What Is Playback Theatre?

Playback Theatre is an improvisational theatre form that takes personal stories told by participants, in the moment, and turns them into compelling theatre. It gives the storyteller and the group a chance to see the story from a different perspective. Because the story is embodied, it provides group members with the opportunity to experience the story and access a greater depth of empathy, transforming the listening from an “intellectual exercise” to a whole-body experience.

THE VOICE FOR THE COMMUNITY

Because of Playback Theatre’s effectiveness in building community and its inherent valuing of all voices, it can play a key role in organizational change efforts. This is especially true for any organization looking to develop a more effective team culture, greater openness and transparency in management, and more participatory leadership at all levels.

TYPICAL OUTCOMES

In the many different settings for Playback Theatre—which include public, semipublic, and private gatherings—Playback Theatre’s outcomes are similar. Dialogue occurs through the public sharing of stories. One story leads to another, connections are made between people, and awareness of differences between people and their life experiences are also brought out. Compassion, empathy, and greater understanding are frequent outcomes. At times, a sense of “everything is fine” can be replaced with a more realistic view, one that honors the current contradictions and existing conflicts, building individual and system capacity to live with ambiguity, which is necessary in any significant change process. Specific outcomes that can be built into a Playback Theatre event include:

• Surfacing critical issues, especially during a change process

• Celebrating successes and endings

• Energizing and clarifying vision, getting back to the heart and meaning of work

• Kicking off event to build energy and buy-in

• Building team cohesion, increasing intimacy and trust

• Bringing depth to data that has been gathered during an organizational assessment, and giving direction for additional data gathering that may be necessary

• Increasing openness and transparency in an organization, especially during a change process

• Breaking norms of indirect/underground communication, bringing conflict out into the open, giving permission for resistance to be openly expressed, and providing people with a chance to see and be seen at a deeper level

• Providing public forum for people to grieve, process, move

• Bringing out the “underheard” or minority voices in a community or organization

EVERY STORY IS IMPORTANT

A key guiding principle for Playback Theatre is a kind of democracy or inclusion, in which all stories and tellers are seen as important. During a Playback Theatre event, the faciliator, or conductor, is always tracking who has told and who has not, as well as patterns in the tellers (like race, gender, and organizational role). The conductor uses that awareness to invite those tellers and stories that have not yet been heard.

Playback Theatre is culturally respectful and adaptable; its motivation is an impulse toward healing and positive change; it operates on both individual and group levels; it is an unfolding process rooted in the moment that is highly spontaneous and trusts in nonlinear movement. It draws on the aesthetic, creative capacities of participants; sees inherent value in play; and it requires a ritual container that is created by the forms and presense of the performers and conductor.

Playback Theatre draws inspiration from the idea of the small community, in which everyone is known to one another. Its brand of storytelling improvisation conforms to characteristics of traditional societies where cultural ceremonies were intimate, communal, redressive, and attuned to the environment (see Fox 1994). From the theory of J. L. Moreno, originator of group-focused role-play approaches, such as sociodrama and psychodrama, it takes the idea that every individual is endowed with a capacity for creativity and spontaneity and can contribute to positive group life. Playback Theatre is also informed by the ideas of the Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, whose concept of critical consciousness suggests the identity clarifying power of personal story. Freire also emphasized the importance of listening, of an open-ended, democratic process of research.

The result of these influences for Playback Theatre is an approach that truly trusts participants’ input. Playback theatre teams perform with no script whatsoever; they come ready to listen; they put their artistic skills and humanity to the service of the tellers. Playback Theatre also has the sense of a “theatre of neighbors,” quite different from the anonymous urban feel of modern theatrical performance. Finally, it is an essential aspect of the Playback Theatre approach that the theatre be constructive. Art alone is not enough. This theatre is not simply entertainment; it has an educative purpose.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

What If No One Wants to Tell?

Usually, if troupe members have done their homework and prepared adequately, including designing the opening of the show to meet people where they are and warm them up to the process, people are open to telling. And if there is some reluctance to tell, then the conductor needs to go back and continue to warm the group up with easy-to-answer, “safe” questions. If no one tells, it is a clear signal to the facilitator that people are either not warmed up enough, or there is not enough safety in the group. One way to address this is by inviting people to talk to another person (dyads) about a structured question or topic. Then the conductor can invite someone to tell a short moment/feeling, or even ask a specific question that he or she is sure some people will be able to answer yes to, for example: “Is anyone experiencing mixed feelings about the change the company is going through, like hopeful and worried?”

What If Someone Goes Too Deep, and Is Emotionally Affected to the Point That He or She Is Overwhelmed or Too Exposed?

In our experience, individuals and groups have an innate wisdom that guides them to tell at a level they can handle. If deep feelings emerge, the conductor is trained to help the teller and group process their feelings and use the situation as a learning moment for the whole group.

What If the Group Does Not Tell the Stories We Want Them to Tell—Stories That Are “Off Topic”?

Stories that might seem “off topic” or superficial are often rich with relevant metaphors and themes, and can become a vehicle for truth to emerge. The following is an example from a performance Sarah Halley did with participants from a variety of Fortune 500 learning organizations. The theme of the gathering was about how to integrate a successful, out-of-the-box initiative by a small subdivision of a large corporation into the larger organization, when the sense of being new and different was an essential component of the initial success. At one point in the performance, a man came to the teller’s chair and he wanted to tell the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, from Goldilocks’s perspective. Typically in Playback Theatre, the teller tells a personal story that is true for him, but there was something about the genuineness with which he presented the story that moved the conductor to go with it. One theme that emerged in the enactment that resonated strongly with the group had to do with the courage it takes to put yourself in a situation in which you are vulnerable and out of your element. And we were left with powerful questions to ponder—Why did she wander out into the woods alone, and where were her parents? Where did her confidence come from? Was this a case of neglectful authority? Was it a story about the drive to take “the road less traveled,” which cannot be tamed by authority? What did the bears represent? In the end, this simple and irrelevant story was anything but that.

An Inappropriate Story

If we meet every story with respect, and trust there is some message of relevance to the group, then no story is truly inappropriate. Playback Theatre is based on the premise that anyone’s story has meaning and it’s our job to bring out the meaning. At one conference, a woman told a story about having different lovers in different cities. Partway through, Sarah realized that the woman had been drinking, and she was using the teller’s chair in part to make a public invitation for someone to “pick her up” that night. Sarah did her best to be as brief as possible during the interview process, and the actors brought out the range of feelings in the story. After the story, Sarah made a “metastatement” about the challenges of being away from home for work reasons. She asked who else in the room travels regularly for work, and many hands went up. She then asked for other feelings about traveling and being away from home. In effect, she built a bridge between her story and the group by making explicit the shared concern/issue that she believed others could connect with.

A Racist Story

We use the term “racist” because we hear that often, but there are a myriad of attitudes and behaviors that could be substituted. There are a number of interventions we might try in the case of a racial story. We might use inquiry to ask questions that get at why the person feels the way he or she does. We might ask how he or she thinks the target of the oppression felt. We might make a metastatement to the audience that brings in some sort of larger social context, or provides a piece of historical information many people may not know. We work to accept the teller and his or her truth, while at the same time acknowledging that there are other ways of seeing the story.

We will also work for brevity and hand the story over to the actors as soon as possible, knowing the actors are trained to use their craft to bring out the feelings of all the people in the story and they will complete the intervention in their enactment. They will work to humanize both the teller and the person who has been the target of the oppression. They will also look for a way to bring in the larger social context. Once the story is done, the teller will have a chance to speak. We might ask if the teller was surprised or learned anything by seeing his or her story. If we sense there is a lot of energy in the audience, we might invite audience members to talk in dyads about how the story impacted them, and how it connects to their lives. We might then ask for feelings—not about the teller, or the teller’s story, but for a feeling of how the story, or a moment in it, connected to their own personal experiences. We might even ask, in the next story, for a time when someone felt targeted for being different. In Playback Theatre’s service of helping a community get to a deeper dialogue, the story told by the racist can be both confronting and helpful.

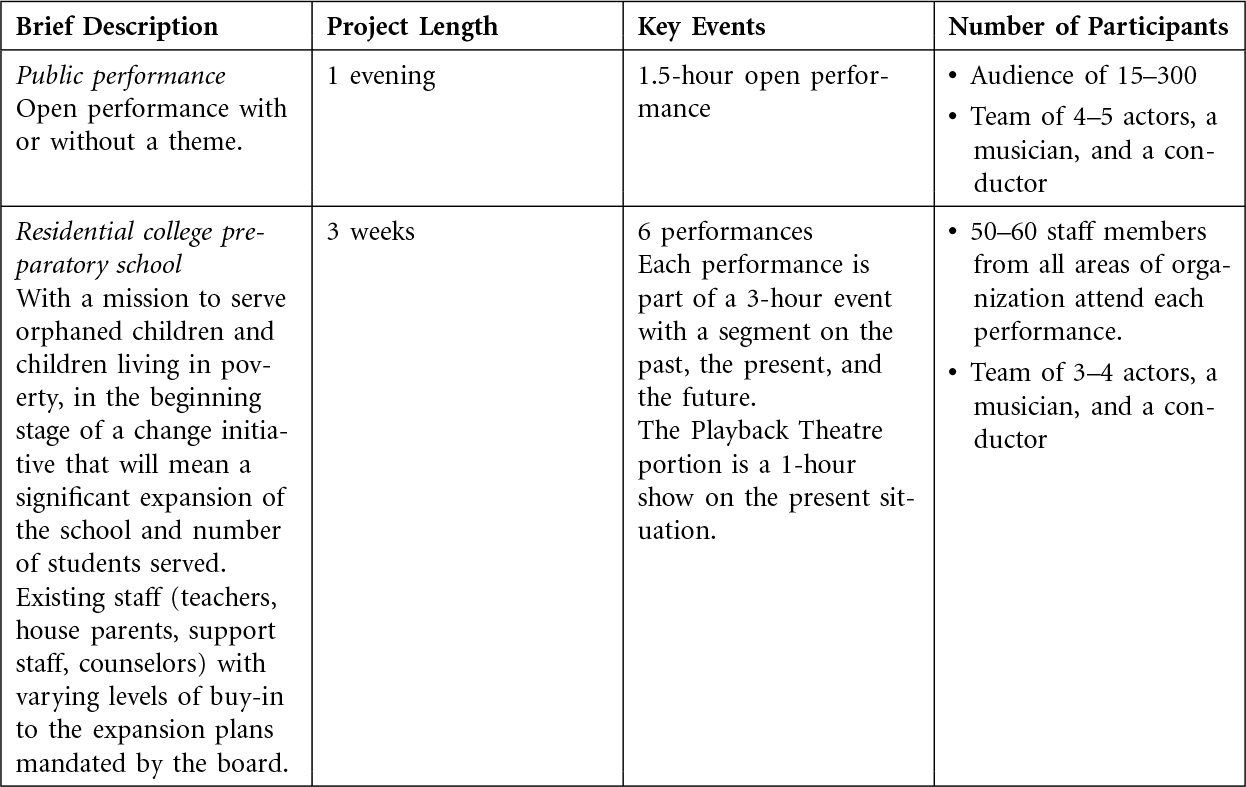

Table of Uses

Getting Started

Playback Theatre is an interactive process. Whether performance or workshop, it begins by warming participants up to each other, to their own stories, and to the Playback Theatre method. The amount of needed container building—that is, structure and boundary setting to ensure safe sharing—depends on who is in the room and the specific objectives of the event.

In a workshop run by a facilitator without an acting team, the steps are different, but the goals are similar. The workshop begins with a variety of activities designed to build connection, safety, and spontaneity. Additional skills like active listening and improvisation are practiced. At some point, personal storytelling is introduced, and participants become performers for each other’s stories. At the end of the workshop, there is a closing process that includes reflection on the takeaways.

Playback Theatre is particularly valuable where an infusion of creative energy is needed, or as a memorable way to bring people together and strengthen the community. This includes kickoff meetings, situations in which the group is in conflict and could use some “aerating,” where increasing trust and risk taking is necessary for success, or where there is some significant loss that the group needs to acknowledge and mourn in order to move on.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Relationships

FACILITATION

The facilitator for a Playback Theatre performance or workshop is the Playback Theatre conductor. The conductor guides and frames the process from beginning to end. Playback Theatre is a highly facilitator-dependent method, and the conductor’s role requires a great deal of skill to accomplish well.

The cornerstone of the conductor’s training is a thorough understanding of group process, including the stages of group development; how to adequately warm up and close a group; diagnostic and intervention skills; thinking on one’s feet; and a strong sense of ritual—that is, a heightened sense of aesthetic form and presence. In addition, the conductor must be skilled in using the Playback Theatre method, understand what forms to use where, how to invite a teller, and make sure the actors know what they need. Finally, the conductor also needs to be a bridge between the organization and the acting troupe, understanding the issues and cultures of both. The conductor training is extensive, and we would refer anyone who is interested in learning how to be a Playback Theatre conductor to the School of Playback Theatre.

Acting teams need to have performing skills along with the ability to listen to and hear the deeper levels of a story. The performers also need to know the culture of the audience. It needs a skilled conductor, and the right context.

Actors need to show depth and humanness of every character, regardless of how “onesided” the teller might be. Actors need to use the content of the story to bring out its social dimension. By social dimension, we mean the factors that are related to the social, historical, and political setting and cultures present in the story—factors that, when embodied and given voice, can both enrich the teller’s experience of the story and open up levels for others in the group to connect the story to their own experience.

Conditions for Success

OPENNESS AND TRUST

Because Playback Theatre is naturally interactive, it will only work if people are willing to tell their stories. There are always some people who are comfortable talking in front of groups and are willing to self-disclose. This fact does not diminish the need to meet the group where it is and intentionally build on opportunities for trust to develop, so that all audience members will at some point feel safe enough to offer a piece of their story. The beginning portion of the performance or workshop is designed to gradually increase the level of risk in sharing, so that participants are incrementally warmed up to telling longer stories. How this is done depends on the specific outcomes of the event, and how connected the group is initially.

Some basic level of trust is necessary for Playback Theatre to be effective, and it is the responsibility of the Playback Theatre practitioner to evaluate the existing conditions and proposed context to insure there is the potential to build enough trust to ask for public sharing of stories. There are certain situations where Playback Theatre is not appropriate because it is not safe to share anything personal.

In public performances and events such as professional conferences, the majority of audience members are unknown to each other. If the performance has a theme, people will have some affinity or desire to explore the theme, which means they may arrive more warmed up or ready to tell. In the case of an existing group, there may be norms in the group that limit what is shared. For example, if trust has been previously damaged in a group, the stories shared initially might not be very deep or risky (which would be appropriate). Increasing the trust level is a basic outcome of all Playback Theatre events.

The most basic requirement of participants is an openness to participate. Not all group members need to have the same level of openness. As long as there is some openness, the Playback Theatre process can be effective. The process itself can help increase openness in more resistant group members.

One example of this kind of opening is a performance we did in a church on Christmas Day during a dinner for homeless and poor people in the community. Sarah observed an initially disengaged man in the back of the room as he slowly opened up to the performance. He moved his seat about three times until he was in the front row, and when we ended, he enthusiastically jumped up and hugged each of us for coming. I couldn’t help but think that if we had passed each other on the street that morning, we would never have greeted each other that way, and it was the human sharing of stories that created that opening.

Theoretical Basis

THIRTY-YEAR HISTORY

Playback Theatre was founded in 1975 by Jonathan Fox and colleagues in the Hudson Valley of New York State. From the start, we experimented with a variety of community applications. We brought Playback Theatre to schools, festivals, organizations, and community centers. We started to travel internationally in 1980. At the same time, we began to offer training in the method. In 1990, in response to the growth of Playback Theatre around the world, the International Playback Theatre Network (IPTN) was founded. Service trademarks reside in the hand of this nonprofit association; Playback Theatre is not a franchised business. Rather, it tries to apply to its own professional community the same generosity of spirit needed by performers on the stage as they enact stories of a local community. Every few years, an international conference brings Playback Theatre practitioners together. Gatherings have been held in Sydney, Australia; Olympia, Washington; Perth, Australia; Rautalampi, Finland; York, England; and Shizuoka, Japan. In 1993, Jonathan started the School of Playback Theatre, of which Sarah is a core faculty member. The school offers comprehensive training for Playback Theatre and enjoys a diverse student body from about 25 countries. Its Libra Project is dedicated to bringing Playback Theatre training to regions needing to rebuild civil society. The school also works with institutional partners to bring the method to organizations and groups.

Playback Theatre has been compared to psychodrama and theatre of the oppressed (TO), created by Augusto Boal, a student of Friere’s. Like Playback Theatre, both methods value a nonscripted approach. However, there are significant differences. In contrast to psychodrama, Playback Theatre does not position itself in the therapeutic domain, even though it is grounded in the concept of constructive change. Unlike TO, Playback Theatre does not begin with any assumptions of what a particular audience’s “oppression” might be, but trusts that the members of a group, through the medium of their personal stories, will always raise issues of importance to them. TO looks for solutions, but Playback Theatre enactments do not. Playback Theatre stories instead engender shared perspectives and deep dialogue. Psychodrama, TO, and Playback Theatre are fully allied in a commitment to voicing truth, which can take courage because powerful forces—personal, social, and political—often urge us to suppress the real story. We believe it is positive and necessary to face the truth of a situation in order to creatively imagine the future.

Sustaining the Results

Measuring shifts in spontaneity, listening, creative thinking, and degree of cohesive community is not easy. As a largely supportive method, the partnering consultant is largely responsible for guiding the organization through the change process and building in measures of success. We have found, over and over, that a single playback event can become a powerful keystone metaphor for the kind of collaborative and responsive teamwork that many organizations strive to cultivate.

The positive outcomes from Playback Theatre are enforced by more than one performance—spaced sometimes up to a year apart—so that participants integrate deeply the experience of openness and creativity that playback promotes. There have been some organizations that have initiated an in-house Playback Theatre performing group comprised of diverse employees, thus guaranteeing sustainability.

It’s hard to say exactly why Playback Theatre works as well as it does. It has a universality and accessibility that has helped it spread to more than 50 countries around the world. It is simple on the one hand, and rich with metaphor and meaning on the other. It taps into a deep need for people to been seen, validated, and part of a community. And it carries with it the power of storytelling to heal and transform.

Burning Question

WHAT COMMITMENT IS NECESSARY?

Commitment on the part of higher-ups needs to include seeing value in play and creative activity and rewarding instead of penalizing participants for their openness (even if they are not in agreement with the content of what has been shared). Leaders must be committed to working with process as well as task goals in their team. Over time, if senior management can demonstrate its openness, others will follow. By the same token, some form of reasonable follow-up needs to be built into the system over time, so that everyone shares some responsibility for making the changes that are needed.

Parting Remarks

Playback Theatre is an action method and a boundary-crosser, spanning the fields of theatre, psychology, oral history, and conflict resolution. It works because people are eager to tell their stories. When members of a group are willing to share honestly their different perspectives on an issue and see them embodied on the stage, evidence indicates that Playback Theatre has led to permanent positive change in organizations.

About the Authors

As an undergraduate, Jonathan Fox ([email protected]) studied oral composition at Harvard, focusing on preliterary epics. His MA is in political science, which he earned in New Zealand while on a Fulbright Fellowship. He spent two years in the Peace Corps in Nepal learning the culture of preindustrial village life. Immersed in the experimental theatre at the beginning of the 1970s, Jonathan also studied psychodrama. All these strands led to Playback Theatre, which has been his principal focus since 1975.

Sarah Halley ([email protected]) has traveled from engineering to organic farming to education to social change work to the performing arts to team building, diversity training, and organizational change work. The red thread that connects them all is a passion for learning, a deep reverence for the interconnectedness of all beings, and a commitment to making the world a better place—all of which are expressed through her Playback Theatre work.

Where to Go for More Information

REFERENCES

Coles, Robert. The Call of Stories. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

Fox, Jonathan. Acts of Service: Spontaneity, Commitment, Tradition in the Nonscripted Theatre. New York: Tusitala, 1994.

———, ed. The Essential Moreno: Writings on Psychodrama, Group Method, and Spontaneity. New York: Springer, 1988.

Fox, Jonathan, and Heinrich Dauber, eds. Gathering Voices: Essay on Playback Theatre. New York: Tusitala, 1999.

Salas, Jo. Improvising Real Life. 2d ed. New York: Tusitala, 1996.

INFLUENTIAL SOURCES

Arrien, Angeles. The Four-Fold Way. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993.

Freire, Paulo. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Seabury Press, 1973.

ORGANIZATIONS

International Playback Theatre Network—www.playbacknet.org

School of Playback Theatre—www.playbackschool.org

OTHER RESOURCE

Tusitala Publishing—www.playbacknet.org/tusitala