CHAPTER 16

Terumo

By Probir Das (Executive Officer of Terumo Corporation, Japan, and Chairman and Managing Director of Asia-Pacific operations)

About Terumo

Terumo is a global leader in medical technology and has been committed to “Contributing to Society through Healthcare” for 100 years. Based in Tokyo and operating globally, Terumo employs more than 25,000 associates worldwide to provide innovative medical solutions in more than 160 countries and regions. The company started as a Japanese thermometer manufacturer, and has been supporting healthcare ever since. Now its extensive business portfolio ranges from vascular intervention, cardio-surgical solutions, blood transfusion, and cell therapy technology, to medical products essential for daily clinical practice such as transfusion systems, diabetes care, and peritoneal dialysis treatments. Terumo will further strive to be of value to patients, medical professionals, and society at large.1

Context

This is an attempt to pen my views on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medical technology industry. With medical technology being immensely diverse and spanning from a simple gauze dressing or syringe to complex remote robots that perform the intricate intravascular repair of the arteries in the heart or that disinfect hospitals, it is difficult to monolithically describe the pandemic's impact on the industry, and hence I must limit this piece to that constraint of generality. Also, the views expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of either my employer or of the several trade associations on whose boards I serve.

Healthcare has a unique dichotomy. On the one hand, it is the most “local” business (perhaps apart from food), with very uneven levels of maturity, access, service, infrastructure, skills, and financing across countries. On the other, the technology providers (both pharmaceuticals and medical devices) are rather globally consolidated, standard-driven multinationals. Healthcare has long been a global challenge; even though it is the second-largest industry globally, it still has not sufficiently served larger parts of the world's population. Functionally, it has somehow been built as “sick care,” with incentives having been structured around creating a cure, rather than “health care” that promotes a healthy lifestyle and wellness. Hence, we have seen an equal measure of failure to deliver quality healthcare, both in developed and underdeveloped countries.

Medical technology serves healthcare. It is the smallest component by size, much smaller than its hospital, diagnostic laboratory, pharmaceutical, and insurance cousins, but in the last half-century, it has enabled the maximum disruption to maximize the impact of the outcomes of those cousins. Yet its contribution has been little understood and often underappreciated by the general recipients of its benefits.

Before the Pandemic

Ours is a century-old medical devices and technology corporation, founded in Japan in 1921, uniquely by a group of scientists, led by the legendary Dr. Kitasato Shibasaburo, with a mission of contributing to society through healthcare. Such was the impact of Dr. Kitasato on medical science and education that he will become the face of the 1000-yen note, perhaps the most circulated Japanese currency note. (See Figures 16.1 and 16.2.)

Terumo Corporation is recognized as a top medical devices company, primarily for its innovations and contribution to advancing newer therapies. If I split our 100-year history into three equally divided historical horizons, the first would be when the company became a bedrock of public health, almost entirely in Japan; the second would be when it diversified into infection prevention and started exploring the global markets; and the last is when it pivoted into the intervention/minimally invasive space, where it is now a firm multinational player with globalization as its key strategic imperative. We currently have three major and distinct business areas: cardiac and vascular, general hospital, and blood and cell technologies. I have led our Asia Pacific region for the past three years.

FIGURE 16.1 Dr. Kitasato Shibasaburo led the group of scientists who founded the company to manufacture the most reliable clinical thermometer possible.

Image credit: Terumo Corporation.

FIGURE 16.2 Dr. Shibasaburo will be honored on the 1000-yen note in 2024.

Image credit: Ministry of Finance, Government of Japan.

Asia Pacific (APAC) is a relatively younger region for us. Before 2012, our many countries in the region worked directly with the headquarters in Japan. It was only in 2018 that we enabled a Singapore-based Asia Pacific headquarters to drive “business-led” management. I had spent 2018–19 envisioning this new HQ and creating board and executive management alignment on its reconstruction and scale-up. Since our erstwhile double-digit APAC growth rates had come down to early singles, we put in place a strategy to get back to double-digit growth. In the 2019–20 period, under the theme of “Reenergize,” we started enabling a business unit–led management structure, created strong and fight-worthy functional capabilities in our regional office, and were raring to unleash this growth strategy on our Asia Pacific focus markets. We aspired to start a reclaim journey to double-digit growth with an 8% goal for 2020–21. This is precisely when COVID-19 hit us smack in our face.

Early Signs

We had started hearing about this virus that was affecting Wuhan, China, at the beginning of 2020. At the time, it was a bit of a faraway problem and not entirely well understood. Right after the Christmas and New Year holidays in 2020 I read that the government of Singapore was to screen all incoming travelers from Wuhan for the virus. By the end of January, we had the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Singapore, and we were already urging our associates to be careful and check their fever status frequently. I started taking it very seriously when I heard that Singapore's DORSCON (Disease Outbreak Response System Condition) was likely to be raised from yellow to orange. I remember that late in January, I assembled my Singapore administration leaders and began putting together a business continuity planning (BCP) team, just in case DORSCON hit orange.

It was a shaky start. There were few references on what should or should not be done. We could not ask for guidance from global HQ; they were still far away from the problem. The government guidance was very helpful. Our BCP members frequently called them and got excellent advice. We cut all cross-border travel, and we instructed our subsidiary entities to stop cross-border travel too. We influenced every single one of our nine APAC-based entities to start BCP teams. Together we started putting in place several policies designing contact-free office entry-exit protocols, split team operations, daily temperature logs, and work-from-home support systems such as more virtual private network lines, cost reimbursements, and many others. Therefore, when the Singapore government declared the circuit breaker stay-at-home preventive measures in April 2020, we were ready. By that time, many of our regional offices were starting to see COVID-19 flare up in their countries, but they too were well prepared for lockdowns from an infrastructure standpoint. Besides, through our intense discussions, regular consulting with various external specialists, and implementing the Singapore government's advice, our young APAC HQ had unknowingly also set a global COVID-19 BCP benchmark.

Early Impact on Business and Mitigation

At the beginning of our fiscal 2020 (April), we had identified that COVID-19 would affect how we worked and performed for quite some time to come. Therefore, to articulate what was required to navigate it well, we focused on commensurate themes in our APAC and India regions. (See Figures 16.3 and 16.4.)

We saw a myriad of challenges, the most impactful ones being:

- The flow of products (supply chain)

- The flow of clinical information (medical promotion/communication between the serving and served)

- The flow of patients (we saw massive shifts in patient behavior; plus policies drastically reduced elective procedure caseloads)

- The flow of money (since COVID-19 created many current and future challenges in healthcare funding)

FIGURE 16.3 We knew that encouragement was required as we began to face the challenges of the pandemic.

Image credit: Terumo Asia Holdings Pte. Ltd

FIGURE 16.4 We focused on themes appropriate to the region.

Image credit: Terumo India Private Ltd

Complex Supply Chain

Manufacturing and distribution of medical devices comprise a very complex global supply chain, for which almost 70% of global revenue is concentrated within some top 50–60 players. This is primarily due to a few distinguishing factors. First of all, no single country or region is wholly contained and self-sufficient with the research and development, component manufacturing, and assembly of its consumption of medical devices. Second, due to the often lifesaving criticality of medical supplies, the supply chain needs to be fast and flexible. Third, given the massive component-level complexities, with components often sourced from other industries such as electronics, the manufacturing of medical devices involves (in most cases) a large ecosystem approach. For most products, most companies generally do not have entirely in-house, end-to-end, component-level manufacturing systems. Finally, healthcare delivery across the world is not as integrated as it ought to be. The complex myriad of public and private health systems, primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary care hospitals, laboratories, radiology centers, blood centers, clinics, rural location sites, and many others, are hardly connected or communicating to each other. This burdens the supply chain with tons of duplication.

Indeed, with these complexities, most medical device manufacturers have always put great importance on integrated business planning (IBP) and business continuity planning (BCP). However, none were prepared for a global shutdown of the extent that COVID-19 enforced! The concurrent lockdowns in virtually every country forced most factories of components and finished goods to suffer capacity loss. Government orders that limited movement kept labor away from their worksites. The shortage of aircraft, ocean freighters, containers, and even space in ports and airports due to congestion, severely attacked the supply chain of medical supplies. I have personally witnessed situations where employees of medical technology manufacturing plants could not access transportation to factories, were threatened with eviction from their rented homes since they were going out to work on lockdown days, and were even mistreated by law enforcement due to early-stage confusion about travel restrictions. Everyone (myself included) has greatly appreciated the selfless dedication of doctors and nurses and has recognized the need to allow their movement and work. Unfortunately, it has taken longer to similarly acknowledge the importance of the manufacturing workers, warehousing and logistic workers, clinical support specialists, and installation and service engineers who comprise the backbone of medical technology and devices. Even as I write this (in April 2021), there is unequal access to vaccination among the core medical technology workers who create the uninterrupted flow of supplies to the doctors and nurses. It is frustrating to see airline workers, delivery workers, taxi drivers, and so many other undoubtedly important frontline roles being vaccinated while the workers who relentlessly risk themselves to keep healthcare technology going are given a lower priority.

Change from a Highly Specialized, One-on-One Communication Legacy

Medical devices see their application mostly in medical settings, directly via the hands of a specialist. This is different from pharmaceuticals, which most often are self-administered by patients. Additionally, as mechanical or electrical engineering devices that draw from user experience, medical devices have a high dependence on incremental innovation; many devices thus have short life cycles of some 18 to 24 months! Finally, devices from two different companies with the same outcome objectives can often have very different engineering and feature elements.

These factors make the continuous and open communication between the user (medical specialist) and the supplier (medical device technical specialists) mission-critical for good patient outcomes. This communication has traditionally been physical, mostly one-on-one, and relatively frequent. While meetings in a group setting (such as symposiums and group training workshops) are common, they never took away from the more personalized forms of hands-on, experience-building sessions (often on simulators), direct interactions while a product was in use, or deep discussions about clinical evidence and data.

This paradigm has seen sudden and complete disruption by the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and in-person contact restrictions. Starting with the lockdowns in March and April 2020, industry representatives had to suddenly (mostly) give up their time-tested model of face-to-face meetings with medical professionals, even though the need to launch newer variants or support procedures remained. This meant a scramble to build or adopt digital engagement, content, and related tools at incredible speed. Just building these tools was not enough; they had to quickly be supplemented by technology to deploy them even from home settings. At the same time, technical specialists who weren't remote-savvy needed to develop skills rapidly for effective remotely work.

This communication complexity and information flow are not limited to users. Many medical devices are part of a “consignment” model, which necessitates regular communication between hospital administrators and medtech's supply chain teams. Besides, the workstyle of the industry was primarily office-based, unlike such industries as consulting or IT-enabled services. On one hand, the need for communication across the spectrum increased manyfold to manage the vast pandemic uncertainties, but on the other hand, organizations quickly had to pivot to being almost 100% remote-based.

Procedure Caseloads and Patient Behavior Vicissitudes

This is an area where the industry has seen orbital shifts in the pandemic period. Elective procedures for dental, ophthalmic, cardiovascular, aesthetics, and several other streams have seen massive declines. The blood-center supply chains are decimated due to massive drops in donor numbers, creating acute blood shortages. Several routine screening programs in cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular, and general health checkups have been hugely affected, creating an alarming future worry that overall health indicators will become uncontrollable due to the late presentations of such diseases.

To better illustrate the overall situation, let us dive into two specialties: cardiovascular and blood centers. When the COVID-19 cases increased alarmingly during the lockdown period, many hospitals were assigned dedicated COVID-19 treatment center status, and ICU beds were reserved for acute COVID-19 patients. Beyond that, many treatment protocols were also altered. High throughput cath labs and cardiac surgery centers reduced their cases to only acute myocardial infarctions, and they spaced the time between procedures to allow for aggressive disinfection of procedure rooms and for the medical teams to don personal protective equipment (PPE). Patients were discouraged from attending outpatient departments in large numbers, screenings were abandoned, and, for the most part, patients were too scared to come into a hospital setting. Most areas of the world saw a 50–70% drop in procedure volumes. (The British Medical Journal reported a 50% drop in patients attending cardiovascular services in the UK, with a 40% reduction in heart attack diagnoses in a hospital in Scotland.) The expectation was that when the lockdowns are lifted, the patients would come back in more significant numbers, but this is yet to happen, partly because intermittent lockdowns continue and partly due to the slow rate of patient reengagement. In the blood center domain, donor collections are depressed 50–80% (depending on geography), and the return is seen in a trickle.

However, for acute respiratory cases, needless to say, the numbers rose to often unmanageable proportions. Hospitals were flooded with COVID-19 patients, and all hands were on deck supporting them. In the initial stages of the pandemic, there were global shortages of PPE, ventilators, infusion pumps, and so on. However, the industry has been able to quickly address these issues, ramp up production, set up new capacity, and even support stockpiling of these critical items to prevent future shortages. The pharmaceutical industry's response in developing the fastest vaccine ever is now known to most.

These changes in the distribution of cases across domains and the cost of response have created a substantial financial depression in many health systems, the extent and impact of which I shall touch upon in the next section.

Financial Complexities Arising Due to the Pandemic

Healthcare providers are severely impacted due to lockdown-induced patient flow reductions and increased operating costs due to PPE, additional testing, and the need to acquire additional equipment such as ventilators, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) equipment, plasma therapy equipment, and so on. In many countries, some hospitals were designated COVID-19 treatment centers and others were non-COVID-19 hospitals. The latter felt a greater financial impact, especially in highly capital-intensive departments like cath labs, cancer centers, renal care centers, and blood banks, where they are still servicing recent investments. A financial sustainability/sentiments survey conducted in India points to the existential risks that small to mid-sized hospitals express. A recent Frost & Sullivan 2021 prediction foresees a 70% reduction in hospital capital purchases. Health sector CFOs are tightrope-walking to balance immediate viability with long-term growth.

For the medical technology industry, major revenue and income depression come from the heavy reduction of all forms of elective procedures. In the Q2–Q3 calendar 2020 period, many organizations saw an almost 60–70% reduction in these areas. The high startup investment into several digital initiatives (enabling work from home, physical distancing, and other measures) has also added to this pressure. In channel-dependent markets, especially in emerging markets in Asia, where the distributors are rather small-sized, receivables had shot up to high-risk levels. Finally, logistics costs increased due to reduced consumption of goods, write-offs of expired short-shelf-life goods, and a four-to-five times increase in shipping costs.

Closer to Home, Some Business Challenges We Faced

We directly experienced the impact of the pandemic in a range of areas:

- We saw a significant (40–80%) drop in elective cardiovascular procedures (like angioplasties, open-heart surgeries, and vascular grafting). In some high-growth countries, this business contributed 30%–75% of our portfolio. Especially in India, which saw one of the world's most stringent lockdowns during the first wave, the procedures were reduced to some 20% of the original volumes.

- Blood donations were reduced to a trickle due to government orders that limited people's movement, especially among college and university youth. Our Southeast Asia business is heavily dependent on blood bag tenders, which were suddenly not forthcoming.

- We saw a very high surge in demand for syringes and needles, where several governments were stockpiling inventory for COVID-19 management and, eventually, vaccination. But our main supply was from our plant in the Philippines, which was heavily affected by the lockdown and movement controls, so we had to quickly find a supply from alternate plants/sources.

- Some markets, especially the Philippines and India, saw a significant drop in channel collection. This, in turn, created Accounts Receivables (AR) issues that we had to focus on and especially resolve.

- We have always physically met with our customers to conduct business with them, run training sessions, manage consignment quality, and provide case support. Now, for the most part, we could not visit our customers in person.

Navigating Through the Complexity

Early in the first quarter of 2020, our company rolled out a global directive to manage the COVID-19 crisis, founded on three simple guidelines:

- All leaders were to keep their employees safe. That was our first and foremost responsibility.

- We needed to do our absolute best to ensure that our supply chain, so critical for patients across the world, was open and protected.

- Our technologies, unique skills, and capabilities were to be totally deployed in alignment with other stakeholders in fighting the pandemic.

Based on these, at Asia Pacific, we quickly did two pivots.

We migrated our twice-a-year performance management system to an agile monthly dashboard-based crisis management system. Starting in April 2020, we migrated all APAC countries, business units, and functions to a standard, common, 20 KPI-based, engaged dashboard. Now all of us were connected via common KPIs, and we were adjusting them as we went through the crisis.

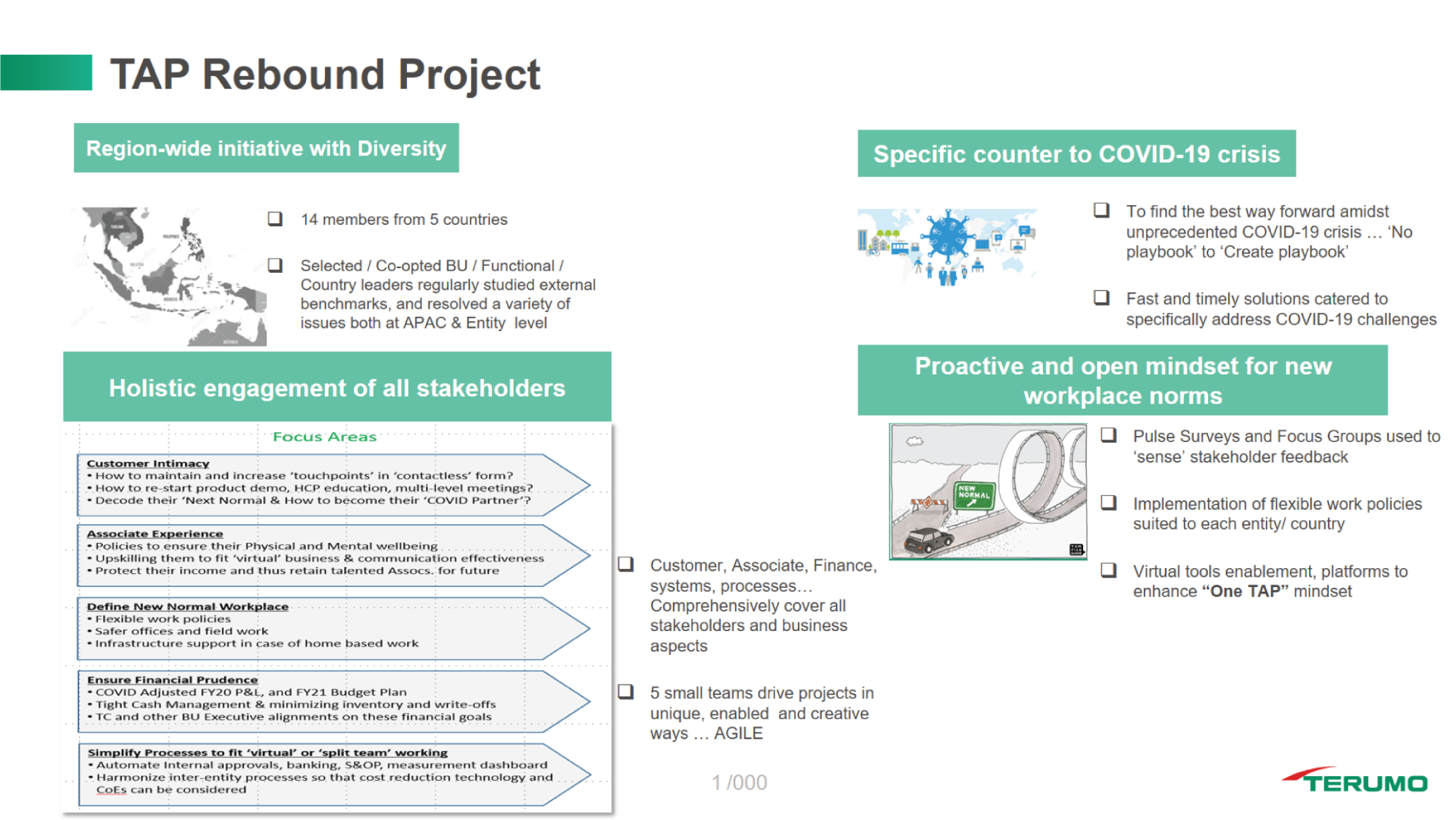

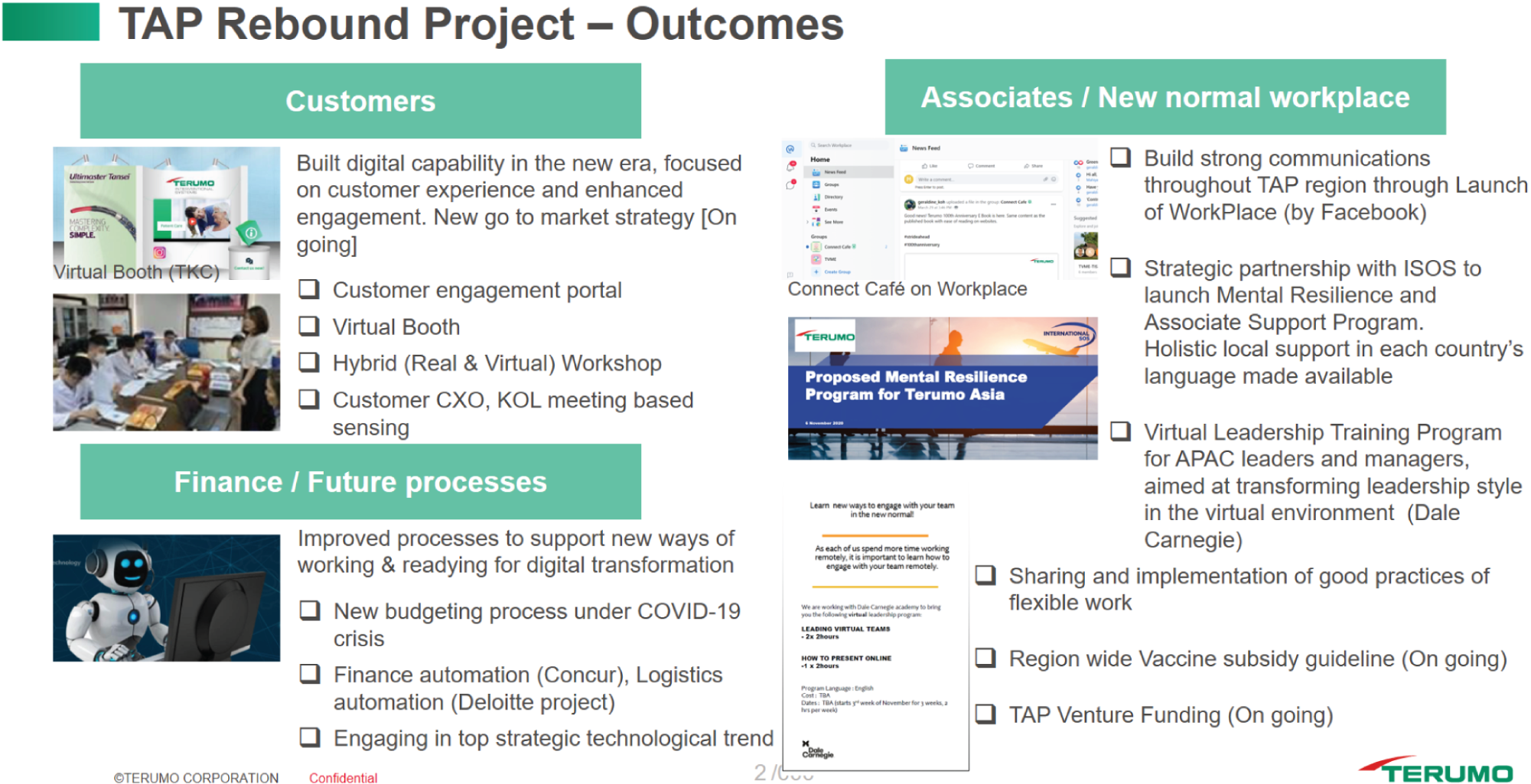

We also morphed our Singapore HQ-based COVID-19 BCP committee to a wider-purpose, multi-geography, multifunctional, cross-hierarchical COVID-19 rebound team. (See Figures 16.5 and 16.6.) Representatives of this team intensely engaged with external specialists, peers, and our entire diverse employee base across the region through spot surveys and focus groups to design a five-point charter that proved very effective for us through the year:

- Customer Intimacy Revival: In the contactless world, this encompassed hearing key opinion leaders (KOLs) and chief experience officers (CXOs), developing new COVID-19 consensus standards with them, migrating our customer training and workshops to electronic formats, and evaluating novel tools such as camera glasses to remotely support critical cases.

- Strengthen Associate Experience: So that our associates remained relentless and energized, despite the hardships and ambiguity thrust upon them by the pandemic, this workgroup enhanced communication by driving new engagement platforms (Workplace by Facebook, Town Halls, and so on). To prepare them for both resilience and skills, we rolled out a Mental Resilience Program (powered by International SOS) and a Virtual Effectiveness – Manager Training Program (powered by Dale Carnegie).

FIGURES 16.5 AND 16.6 Representatives of our COVID-19 rebound team engaged with external specialists, peers, and our diverse employee base to design a five-point charter.

Image credits: Terumo Asia Holdings Pte. Ltd.

- Define and Enable New Normal Workplaces: This team worked to advance flexible work policies, create work-from-home support infrastructure/subsidies, and add contactless/safety features to our offices to ensure that we were taking the best care possible of ourselves.

- Drive Balance Sheet–Based Financial Prudence: We significantly improved our cash management, trained business unit leaders on the balance sheet/asset management approach (they were previously more focused on P&Ls), and rolled out channel financing schemes and aggressive AR collection programs in target countries. Additionally, this team worked to align all country and business unit operations and global headquarters to roll out quarterly adjusted forecasts that became our performance standard for 2020.

- Simplify Processes: Our former systems were very office-based. Hence, we quickly needed to dismantle many of them, convert others to be fit for remote work and split teams, and reduce decision-making time.

Quickly Mitigating Revenue and Profit Risks

The rapid drop and very slow recovery of cardiovascular cases and blood supply in Southeast and South Asian markets posed a considerable risk to our financials. Yet, at the same time, we sensed some unplanned opportunities with our syringe and infusion pumps, emergency bypass systems, blood component collection systems, and disinfection robots (from a partner company). If swiftly adopted, these products could potentially strengthen our customers’ ability to scale their fight against COVID-19. Most of these efforts were complex, with global supply chains, long lead times, and forecast-based manufacturing capacities.

But our mission helped. Distant and diverse teams came together, rallied with each other, found unique and unprecedented methods, and ultimately successfully executed these projects. Just as an illustrative example, we supplied 45 machines to help a country's government set up its plasma therapy program within three months. Historically, we had deployed only two or three machines in a year. Sourcing, manufacturing, and the supply chain were scaled rapidly; we conducted application workshops across more than 30 far-flung sites through a hybrid tool consisting of videos, remote training, and 24/7 troubleshooting.

The rapid response not only helped us proudly live our mission, but also to a good extent helped us mitigate shortfalls from other therapy areas.

Future Outlook

Some significant trends have been identified. A disruption of this magnitude brings with it some significant shifts in habits. Plenty of changes are happening, but the more significant ones that I have experienced include these:

- Healthusiasm: Not only do we see increased use of masks and hand sanitizers (masks are authority mandated anyway), but I see people biking, running, walking, exercising, and meditating more. Perhaps quarantined living, the slipping sense of security, the realization that such huge health risks exist, and the recognition that life is so fickle has driven us to care for our bodies and minds more.

- Online Shopping Is the New Normal: With the massive rise of electronic shopping that allows far greater browsing than visits to physical stores, the habit is gradually permeating beyond personal or household purchases even to organized buying. Once the shopper learns how to check options, solid decision-making processes are suddenly fluid.

- From “Just in Time” to “Just in Case”: Again, this started at home with everyone buying an extra box of masks, a few more bottles of sanitizer, and even a pulse oximeter, but it suddenly became a massive phenomenon of institutional pandemic stockpiling of syringes, needles, life support equipment, and many other items.

- Rise of Compassion: Beautiful to see, compassion is suddenly mainstream. Everyone began ending a conversation with “stay well,” households cooked for stranded dormitory workers, and bosses were suddenly less bothered about what time a person started work. People managed through empathy what they could not manage through a plan. Louis Vuitton made sanitizer! “Compassionate” brands are everywhere now. Compassion is also a key determinant of employee “trust” currency. I foresee organization-wide compassion measuring metrics that will eventually determine both leadership capability and share prices.

- Telehealth: The future just fast-forwarded a few decades. Man landed on the moon in 1969 with health vitals of the famous moonwalkers monitored remotely from Houston, Texas. Unfortunately, half a century later, even Johns Hopkins was doing some 90 teleconsultations in a month. This went up beyond 10,000 in 2020. No traveling to the clinic, no needing someone to come along, no parking, no running around – the doctor just saw you in a jiffy, albeit virtually. I bet a lot of this will continue even beyond COVID-19.

There will never be a time when patients will not need to be supported through Terumo's technologies; hence our job in the future is cut out for us. However, models are likely to change, digital is expected to determine how success will look, and COVID-19 will likely stay with us for much longer than we had envisioned even six months ago. As I wrote this piece, we saw huge resurgence waves of the pandemic around Asia. We have moved from a “fight COVID-19” stage to a “live with COVID-19” stage.

Our fight will continue. Yes, when the pandemic hit, I had thought I should overcome it with enthusiasm – the enthusiasm to fight on, to try new things, experiment, and energize myself so that I could egg others to move on. That sprint quietly turned into a marathon, and a long one at that. But I realize that at some point during my run, I developed the marathon muscles. Not that I have lost the enthusiasm streak completely, but I am now more than enthusiasm driven; I am charged by the endurance to see this race through to the end. And, with countless unsung heroes pushing me a bit more every day, I know I am not alone.

About the Contributor

Probir Das is an executive officer of Terumo Corporation, Japan, and the chairman and managing director of Terumo's Asia Pacific operations. He has over three decades of medical technology experience and has worked extensively across Asian markets. Given his keen interest in policy-shaping, he is actively engaged in advocacy as director of the board for APAC Med and Medical Technology Association of India (MTaI). He held past senior roles with NATHEALTH, FICCI, and AdvaMed. Probir also has over a decade's teaching experience, specifically around strategy, leadership development, coaching, and performance management. His passion for med tech sees him mentor startups and entrepreneurs. Probir currently resides in Singapore.

Note

- 1 Corporate profile, 2021, https://www.terumo.com/about/profile/