19

Question Design in Conversation

1 Introduction

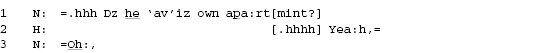

Questions are pervasive in ordinary conversation and institutional interaction, alike. Questions typically initiate sequences as in Extract (1).

Here, N requests information that she lacks (whether ‘he’ has his own apartment or not), making an answer that provides this information a relevant response. H’s answer confirms that he does have his own apartment, and N receipts this as informative with “change-of-state token” oh (Heritage, 1984a). This basic structure of question sequences led Bolinger (1957: 4) to say that a question “is an utterance that ‘craves’ a verbal or other semiotic response (e.g. a nod). The attitude is characterized by the speaker’s subordinating himself to his hearer.”

However, this characterization proves to be too limited to embrace all that questions are used for in social interaction. Depending on such factors as how they are designed, who is asking them, and the social and sequential context within which they are asked, questions bring about diverse interactional consequences. In fact, contrary to Bolinger’s comment, questions are a powerful tool to control interaction: they pressure recipients for response, impose presuppositions, agendas and preferences, and implement various initiating actions, including some that are potentially face-threatening (Brown & Levinson, 1987). In Sacks’ words (1995a: 54), “As long as one is in the position of doing the questions, then in part they have control of the conversation.”

Many conversation analytic studies discuss different question designs, their interactional imports and the actions they are used to accomplish in various contexts. These studies document how question design serves as a key resource to organize our social lives. This chapter provides an overview of the findings of these studies.

2 Questions

What is a question? is a question that has no simple answer, for the form a question takes is quite diverse. Studies on questions in spontaneous interaction suggest that there are three contributing factors that are regularly deployed to do questioning across languages: grammar, prosody and epistemic asymmetry (see Stivers, Enfield & Levinson, 2010). This section illustrates how these three resources serve as indicators of questions in interaction.

Let us first consider polar questions. Many languages have grammatical marking that distinguishes polar (yes-no) questions from assertions (see Dryer, 2011a). Typologically, the most common way of marking polar questions is with question particles. Finnish, Korean, Japanese, Lao and Tzeltal are examples of languages among many others that have question particles that appear in various positions of sentences. Many Germanic languages have a dedicated word order that distinguishes interrogatives from assertions. In addition, most languages have more than one way of asking polar questions. In English, for instance, a single proposition can be questioned in the inverted interrogative (e.g. Did he come?), a negative interrogative (e.g. Didn’t he come?) or a tag question (e.g. He came, didn’t he?). Yet, questions cannot be defined by any of these linguistic criteria, since an utterance in these interrogative formats does not necessarily do questioning, and an utterance in a non-interrogative form may serve as a question (Bolinger, 1957; Labov & Fanshel, 1977; Pomerantz, 1980; Heritage, 2012b, this volume).

Interrogative prosody is also commonly deployed in polar questions. In such languages as Italian, Romanian and Arabic, rising intonation is the only conventionalized means to ask polar questions (Dryer, 2011a; see also Rossano, 2010). In languages that have formal resources to mark polar questions, too, rising intonation is commonly found with declarative questions (e.g. He didn’t come?) as well as questions in the interrogative syntax (e.g. Did he come?) (Quirk, et al., 1985). However, studies offer evidence that it is misleading to treat rising intonation as strongly indicative of a polar question: polar questions are not necessarily marked with rising intonation, and rising intonation does not necessarily mark an utterance as a polar question (Geluykens, 1988; Selting, 1992; Stivers, 2010; Weber, 1993; see also Couper-Kuhlen, 2012). For instance, Stivers (2010) reports that 18% of declarative questions in her corpus are not produced with rising intonation. Thus, intonation is not a reliable indicator of questions, either. Moreover, there are languages that do not seem to have either conventionalized grammatical resources or intonation to mark polar questions (see Levinson, 2010, for instance, on Yélî Dnye). How, then, do participants recognize utterances as questions?

Previous studies show that domains of knowledge play a crucial role. Labov and Fanshel (1977) report that when a speaker makes a statement about an event that falls into the recipient’s knowledge domain (B-event statement), it functions as a polar question and elicits confirmation or disconfirmation (see also Heritage, 2003a, 2012a, this volume; Heritage & Roth, 1995; Stivers & Rossano, 2010). More generally put, it is recipient-tilted epistemic asymmetry that contributes to hearing an utterance as a question (Stivers & Rossano, 2010.). Below is an example from an exchange between an interviewer (IR) and an interviewee (IE) in a British news interview.

The interviewer’s utterance is a declarative sentence and is not produced with rising intonation. Nonetheless, the interviewee treats it as a polar question and responds to it as such by providing a confirming answer. The interviewer’s turn is recognizable as a question because of the nature of the information being sought: it addresses the subjective sentiment of the interviewee, which the interviewee has epistemic rights to confirm or disconfirm. Thus, interactants’ shared understandings regarding who is expected to have information plays a crucial role in making declarative utterances recognizable as questions. Levinson (2010) suggests that this seems to be what speakers of Yélî Dnye rely on in distinguishing polar questions from assertions: when an utterance addresses information that the speaker does not know but a recipient is likely to know, it is treated and responded to as a polar question or a confirmation request.

Thus, while most languages have grammatical and/or prosodic resources that are commonly associated with questioning, these resources do not definitively establish questions. Recipient-tilted epistemic asymmetry is a major contributing factor.1 This is true with content (wh-) questions as well. Traditionally, content questions are characterized by interrogative words (what, who, etc.), which all languages are said to have (Dryer, 2011b). However, an utterance including an interrogative word does not necessarily do questioning. For instance, an utterance “Do you know who’s going to that meeting?” is hearable both as a pre-announcement and as an indirect content question requesting information (Terasaki, 2004 [1976]: 202). Putative epistemic states of participants are a crucial factor that participants refer to in understanding an utterance like this (see Heritage, 2012a, this volume).

In such languages as English (Quirk, et al., 1985) and German (see Selting, 1992), content questions are associated with falling intonation. However, in spontaneous interaction, falling intonation does not systematically occur with content questions (Selting, 1992, 1996b; Couper-Kuhlen, 2012). For instance, Selting (1992, 1996b) shows that content questions in German are produced both with rising and falling intonation, and intonation, independently from the grammatical structure, contributes to distinguishing between activity types.

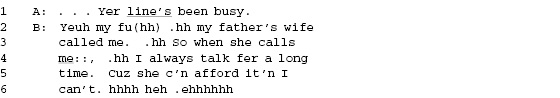

Moreover, while most content questions are marked with interrogative phrases, there are means to accomplish parallel actions without them. Pomerantz (1980) documents an interactional practice that regularly solicits an account, thus functioning as a why- or how come-question, without deploying the interrogative words. Here again, it is epistemic asymmetry that plays a key role. In line with Labov and Fanshel (1977), Pomerantz suggests that information can be classified as either a Type 1 knowable or a Type 2 knowable. The former is information that a speaker has both rights and obligations to know, while the latter is information to which a speaker has limited access by virtue of being occasioned. Pomerantz shows that reference to a Type 1 knowable that is a Type 2 knowable to the recipient routinely elicits telling about relevant information. Excerpt (3) is an example. A has reached B on the phone after several attempts.

At line 1, A tells ‘her side’, displaying limited access to an event in B’s domain of experience. B, being the subject-actor of her own experience, is expected to have more complete information about what has been happening to keep her line busy. And that is what B tells A in response. Thus, by telling the recipient’s ‘side’, a speaker encourages the recipient to ‘volunteer’ the information being sought without explicitly requesting it through why or how come.

This section has shown that there is no single formal way to identify a question, though languages usually have grammatical and/or prosodic resources that are associated with questions. Epistemic asymmetry appears to play a primary role in making an utterance recognizable as a question, and this is why speakers of languages without formal means for asking polar questions do not have problems in identifying them (e.g. Yélî Dnye). Moreover, interrogative lexico-morphosyntax and prosody can be reserved for other interactional goals. In the next two sections we turn to interactional consequences that different designs of questions bring about: section 3 illustrates various epistemic stances conveyed by designs of questions and resulting interactional consequences; section 4 discusses various constraints that questions set up for answers through details of their designs.

3 Questioning and the Epistemic Gradient

The previous section showed that grammar and prosody do not reliably identify questions. However, this is not to say that grammatical and prosodic features of question design have no interactional import; on the contrary, they are used to convey stances of various kinds. This section illustrates how question designs are used to convey epistemic stances.

Heritage (1984b: 250) writes:2

a questioner, in addition to proposing that an answer should be provided ‘next’ by a selected next speaker, also proposes through the production of a question to be ‘uninformed’ about the substance of the question … Moreover the questioner also proposes by the act of questioning that the recipient is likely to be ‘informed’ about this same matter. Thus a standard way of accounting for the non-production of an answer is for the intended answerer to assert a lack of information, and hence, an inability to answer the question as put.

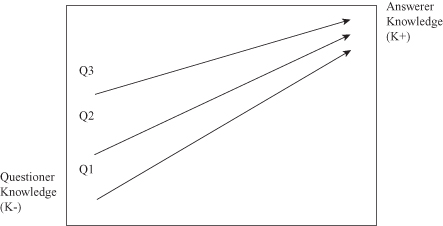

Here Heritage suggests that knowledge asymmetry is constitutive of question-answer sequences. In recent work, this has been discussed in terms of an epistemic gradient. The idea here is that in asking a question a speaker can propose, through the details of the question’s design, that the gradient is relatively steep or relatively flat (Heritage, 2008a; see also Heritage, 2010, this volume). Consider the following three questions:

| Q1) Content question: | Who were you talking to? |

| Q2) Interrogative question: | Were you talking to Steve? |

| Q3) Tag question: | You were talking to Steve, weren’t you? |

Heritage (2008a, 2010) argues that these questions differ in terms of the epistemic stance they convey: Who did you talk to? suggests the speaker has minimal knowledge about the inquired person; You talked to Steve? suggests that the speaker is predisposed to a yes answer; You were talking to Steve, weren’t you? suggests that the speaker strongly believes that this is the case and is simply seeking confirmation (see also Pomerantz, 1988; Raymond, 2010; see also Heritage & Raymond, 2012). As a result, these questions imply different epistemic gradients between questioner and answerer as represented in Figure 19.1.

Figure 19.1 Question design and epistemic gradients

(Heritage, 2008a, 2010; see also Heritage, this volume).

Different languages index degrees of (un)certainty with different resources. In Japanese, for instance, final particles are the major resource for doing so (Hayashi, 2010; Hayano, in prep.). In addition to such grammatical resources, prosody also indexes degree of epistemic (un)certainty. Couper-Kuhlen (2012) suggests that falling intonation in polar questions is associated with greater certainty, and rising intonation with lesser certainty. Thus, the slope of the epistemic gradient may be finely tuned employing grammatical and prosodic resources.

The epistemic stances adopted through questions’ designs can have a significant impact on ensuing interaction. Raymond (2010) examines interrogative questions and declarative questions in interactions between health visitor nurses (HV) and new parents, in which HVs are supposed to balance between being professional/institutional and being friendly/personal. He shows that interrogative questions portray the questioner as an unknowing party and invite the recipients to produce answers with elaboration on the issue. On the other hand, declarative questions convey that their speakers know the issues and invite the recipients, who have superior rights to the matter, to provide minimal confirmation so they can move on to the next agenda item. Consequently, the latter form underscores the institutional, impersonal nature of the setting more than the former does. Thus, an epistemic stance embodied through question design reflects participants’ orientations and a sensitivity to “socioepistemic” issues (Heritage, 2010: 50).

This section has discussed how grammatical and prosodic designs of questions convey various epistemic stances. While marking recipient-tilted epistemic asymmetry is a constitutive feature of questions, different designs are used to claim varying degrees of (un)knowledgeability. Managing knowledge, however, is not the only matter dealt with in question-answer sequences. Through details of question design, questioners set up multiple constraints for answerers. The next section turns to such constraints: presuppositions, agendas and preferences.

4 Presuppositions, Agenda Setting and Preferences

In traditional linguistic views, questions are distinguished from assertions in terms of speakers’ putative epistemic stance (i.e. lack of epistemic certainty), or the action they perform with regard to the propositional content of a sentence (i.e. request for information). In Bolinger’s words (1978: 104), a polar question “advances a hypothesis for confirmation.” In Lyons’s words (1977: 757), questions contain a “variable” and questioning invites recipients to “supply a value for this variable.” What underlies these views is an assumption that questioning is primarily concerned with information—requesting and obtaining information. However, questions do not solely request information. They are employed as a powerful tool in controlling interaction, and they do so by imposing various constraints on answerers. This section illustrates three major constraints that questions set up: presuppositions, agendas and preferences.

4.1 Presuppositions

Questions convey speakers’ presuppositions (e.g. Clayman, 1993b; Heritage, 2003a; Levinson, 1983; Lyons, 1977). For instance, the content question When did she leave town? presupposes that she left town at some point prior to the asking of the question. The polar question Are you using any contraception? (Heritage, 2010: 47) presupposes that the recipient is sexually active. The alternative question Do you want to arrange our next meeting now, or later? presupposes that the recipient wants to arrange a next meeting at some point. Any direct answer to a question accepts its presuppositions as valid, and since this is precisely what questions ask for, it takes interactional work to refute the presuppositions (Ehrlich & Sidnell, 2006; Heritage, 2003a).

While question presuppositions are usually shared and unproblematic, questioners can embed hostile presuppositions in questions (Heritage, 2003a). In Extract (4), an interviewer (IR) asks a content question loaded with a presupposition, which the interviewee (IE) rejects in his answer.

IR’s question “What’s the difference between your Marxism and Mister McGarhey’s communism.” (lines 1–2) presupposes that the interviewee is a Marxist. The interviewee begins his turn in a way that appears to be the start of an answer, which would accept the presupposition (“er The difference is … ” in line 3). However, as the turn develops, it does not answer the question but instead rejects the validity of the question by rejecting its underlying presupposition.

Questions, therefore, neither simply nor innocently request information. They convey, and impose on recipients, questioners’ beliefs. They do so through the designs of questions as well as whether and what sort of question preface is included. Additionally, different question designs embed presupposition at varying degrees of depth (Clayman & Heritage, 2002b). Such presuppositions can be a resource to convey confrontational messages. When asked such questions, answerers face a choice between: (a) providing a relevant answer and accepting the presupposition(s); or (b) bringing the presuppositions to the surface of the interaction, rejecting them but not answering the question, and thus potentially being heard as ‘evasive’. This is one of the ways in which questions bind conversationalists “in a web of inferences” (Levinson, 1983: 321).

4.2 Agendas

Another way in which questions constrain recipients is by setting agendas (Boyd & Heritage, 2006; Clayman & Heritage, 2002a, 2002b; Heritage, 2003a, 2010). In addition to the formal constraints in which a question places an answerer—for example answering a why-question with a reason or answering a polar question with an affirming or disaffirming answer—a question also sets two agendas: a topical agenda (what is being talked about) and an action agenda (what the speaker is doing with the question). Answerers usually conform to agendas set by questions, but not invariably. See Extract (5) for an example. The interviewer (IR) asks Edward Heath (IE) if he likes his main political rival Harold Wilson. This polar question sets as an action agenda a subjective evaluation of Wilson using a format that makes a yes- or no-answer due. The IR sets the topical agenda to discuss Harold Wilson.

Heath conforms to the question’s topical agenda, but not to its action agenda. His resistance of the action agenda is partially through his non-adherence to the formal constraints of the question. He addresses the topic of Wilson but with a preface which shifts the agenda from whether he likes Wilson or not to whether he deals with him well or not (lines 3–9). However, he does not get away with this response. The interviewer re-issues his question pursuing yes or no at line 10 and then again at line 16 after Heath again changes track (lines 12–14). As is exemplified here, while answers can and do resist the agendas set by questions, when they do so, they are seen to be evasive and provide questioners a warrant to renew the question (Clayman, 1993b; Heritage, 2003a).

Similarly, in Extract (6) below, the question “Where was her cancer.” (line 25) sets as its topical agenda the mother’s cancer, and the type of cancer as its action agenda. Formally, as a where-question, it constrains the answer to a location.

The patient’s response conforms to the formal constraints of the question by giving a location (“Arizona” in line 27) but moves away from both the topic and the action agendas at the outset of her turn. She eventually does comply with the action agenda by telling the physician that “she had(:)/(’t) like- in her stomach somewhere” (lines 31–2) but does not fully comply with the topical agenda insofar as the discussion of the mother is relatively far away from the cancer and more about her mother’s inaction.

Moreover, the scope of the agenda can be set relatively broadly or relatively narrowly. Content questions generally set agendas more broadly than polar or alternative questions (Heritage, 2003a; Heritage & Robinson, 2006b). For instance, the physician’s opening question What can I do for you today? sets both topical and action agendas broadly: it sets the topical agenda as broadly as a question could and it allows both phrasal and clausal answers (though phrasal are treated as generally preferred; see section 4.3). Heritage and Robinson (2006b) report that such open, general inquiries are more likely to solicit longer problem presentations than polar questions from patients.

In short, through various aspects of their design, questions set up agendas and specify what answerers should do in their response turns. Once a question is asked, an answerer cannot neglect its agenda without interactional consequences.

4.3 Preference Organization in Questioning

Preferences are another set of constraints that questions impose upon recipients. When questions are asked, there are a series of binary possibilities for what their recipients do in response: they may produce an answer response or nonanswer response; the answer may or may not conform to the questioners’ displayed expectations; the answer may or may not take the form that was specified by the question; when there are more than two participants in interaction, an answer may be produced by the addressed recipient or a non-addressed recipient. How these alternative responses are formulated reveals that one of them is preferred to the other: preferred responses are generally produced without delay, mitigation or hedging, while dispreferred responses tend to be delayed, mitigated and hedged (Heritage, 1984b; Pomerantz, 1984a; Sacks, 1987; Schegloff, 2007b; see also Lee, this volume; Pomerantz & Heritage, this volume). In this subsection, we discuss layers of preferences that questions posit through their design.

4.3.1 Preference for Answers Over Nonanswer Responses

Questions make answers conditionally relevant (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973): question recipients are accountable for providing answers, and when an answer is missing, it is “officially absent” (Schegloff, 1968: 1083). Indeed, when an answer is missing, what we often observe instead is a response that accounts for its absence, for example, I don’t know (Heritage, 1984b; see also Clayman, 2002b: 242–3; Metzger & Beach, 1996).

Stivers and Robinson (2006) argue that answer responses are systematically preferred to nonanswer responses based on four observed features: (i) answer responses are more common than nonanswer responses; (ii) nonanswer responses are regularly delayed, hedged and expanded with accounts; (iii) when a response is absent, that is typically treated as a harbinger of disalignment rather than of a nonanswer response; (iv) speakers do interactional work to provide answer responses, even when a nonanswer response is a readily available alternative.

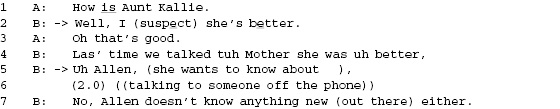

The fourth feature is exemplified in Excerpt (7). A’s question puts B in the position where she is accountable for providing an answer. As it turns out, however, B does not know how Kallie is doing, as shown at line 7 when she says “Allen doesn’t know anything new (out there) either.”

Instead of saying I don’t know, B works to provide an answer response, giving her guess (line 2), referring to the last occasion when she saw Kallie (line 4), and even goes further by requesting help in answering the question from a third party (lines 5–7). That interactants work to avoid nonanswer responses shows that the conditional relevance established by a question is robust.

4.3.2 Preference for Affirmation Over Disaffirmation

A second aspect of preference organization concerns alternative responses that are both conditionally relevant: preference for affirmation/confirmation over disaffirmation/disconfirmation. Polar questions make either a yes-answer or no-answer relevant (Raymond, 2003). Beyond this, polar questions typically display the speakers’ preference for one of them over the other and answers that converge with that expectation are preferred over those that do not (Heinemann, 2005; Heritage, 1984b; Pomerantz, 1984a; Sacks, 1987; see also Lee, this volume; Pomerantz & Heritage, this volume).

In general, in English, polar questions in the following constructions prefer a positive yes-answer (Heritage, 2010):

- Positively formulated straight interrogative (e.g. Have you heard from her?)

- Positive statement + negative tag (e.g. You’ve heard from her, haven’t you?)

- Positively formulated declarative questions (e.g. You heard from her?)

- Negative interrogative (e.g. Haven’t you heard from her?) (Bolinger, 1957; Heritage, 2002c)

On the other hand, questions in the following forms prefer a negative no-answer.

- Negative declaratives (e.g. You haven’t heard from her. and You never heard from her.)

- Negative declaratives + positive tag (e.g. You haven’t heard from her, have you?)

- Positive interrogative + negative polarity item (any, ever, at all, yet, etc.) (e.g. Have you heard from her yet? (Horn, 1989; Heritage, 2003a; Heritage, et al., 2007)

- Positive interrogative + negatively tilted adverbs (seriously, really, etc.) (e.g. Have you really heard from her?) (Heritage, 2003a)

For instance, see Extract (8). A asks B about the food in a cooperative housing arrangement. A’s question at line 1 is a positive declarative question preferring a yes-answer.

This question does not successfully elicit an immediate answer (line 2). A understands this delay as a harbinger of a dispreferred no-answer, and re-issues the question, reversing the polarity of it to accommodate the incipient no-answer (line 3). In this case, it turns out that the issue is not really about whether or not there is a good cook: there is no appointed cook (line 4). However, we can see that the questioner conveys a preference for a particular answer through the formulation of the question and attempts to design the question to maximize the chance of getting a preferred response.

Preferences conveyed through question designs can have robust and serious consequences. In their study on physicians’ questions in primary-care visits, Heritage, et al. (2007) demonstrate that a yes-preferring question (“Is there something else you want to address in the visit today?”) is significantly more effective in soliciting patients’ concerns than a question with negative polarity (“Is there anything else you want to address in the visit today?”). This study reveals how consequential seemingly trivial word choice in questions can be.

Preference in question design can be more complex than we have thus far discussed. A sequence can involve cross-cutting preferences when a question’s formal (grammatical) and action preferences are at odds (Pomerantz, 1984a; Schegloff, 2007b). For instance, the question You’re busy, aren’t you? conveys the speaker’s expectation for a no-answer as far as the formulation is concerned. However, if this question is produced as a pre-request (Schegloff, 2007b), a preferred, aligning response would be a go-ahead, which would encourage the production of the projected request. Thus, this question design poses a preference that cross-cuts the action-type preference, often working to mitigate the face-threatening nature of the projected action (here, for instance, a request) (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Heritage, 2010; see also Heritage & Pomerantz, this volume; Lee, this volume).3

This preference for affirmative answers has proven to be robust across languages. For instance, Stivers, et al. (2009) report that affirmations are produced faster than disaffirmations across ten typologically diverse languages. Thus, whatever language it is that they speak, speakers of polar questions do not put themselves in the utter K− position. They convey predispositions through details of question design, pressing recipients into either yes or no. Furthermore, questions specify the form that answers should take. The next section discusses this aspect of preference organization.

4.3.3 Preference for Type-Conformity Over Nonconformity

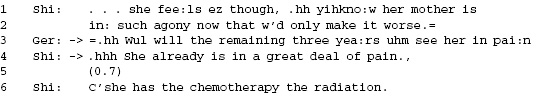

Earlier, it was suggested that questions embody presuppositions, which any direct answer, whether affirming or disaffirming, would accept. Raymond (2003) examines how presuppositions associated with a polar question can be either accepted or resisted through the form of the answer. He distinguishes two kinds of answers: type-conforming answers which are those containing a yes or no, on the one hand, and nonconforming answers which convey affirmation or disaffirmation by different means, on the other hand. He shows that type-conforming answers are systematically preferred, and nonconforming answers are produced ‘for cause’—namely to take issue with the presuppositions of the question. See Extract (9). Shirley asks Gerri about a woman who is dying of cancer. This polar question makes either yes or no relevant, a type-conforming answer. However, Gerri’s answer contains neither.

Though Shirley’s nonconforming response affirms the proposition of Gerri’s question, conveying that the woman “will” be in pain, by withholding a yes or no token, it pushes back on the question’s presupposition that the woman has not been in pain up until this point. Nonconforming answers are thus one way that answerers resist the presuppositions of a question (see Ehrlich & Sidnell, 2006; Stivers & Hayashi, 2010; see also Lee, this volume).

While Raymond (2003) focuses on polar questions, other kinds of questions constrain the type of response as well. Alternative questions confine answers to one of the alternatives provided. Content questions specify the type or class of answer expected via question words: a person for who-questions, an object, action, event, and do on for what-questions, a place for where-questions, a time reference for when-question, an account for why-questions and a manner or means for how-questions (Bolden & Robinson, 2011; Robinson & Bolden, 2010; Schegloff, 2007b; Schegloff & Lerner, 2009). Further, content questions generally prefer responses in the form of phrases, and clausal responses are produced to resist some aspect(s) of the questions and thus constitute nonconforming responses (Fox & Thompson; 2010). Thus, type-conformity is yet another constraint that questioners impose upon recipients.

4.3.4 Preference for Selected Speakers to Answer Over Nonselected Speakers

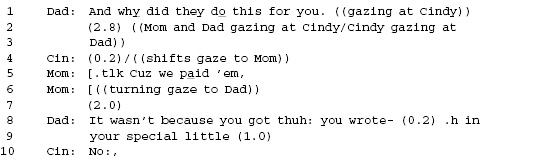

The final aspect of preference we discuss in this section does not concern the kind or form of a response, but who answers the question. It was mentioned earlier that once a question is asked, its recipient is accountable for providing an answer to it (see Hayashi, this volume, on turn allocation). The distribution of responsibility becomes more complicated in multiparty interaction. When a question is designed to select one of the recipients as next speaker (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974; see also Lerner, 2003), but an answer is not forthcoming from the selected recipient, another, nonselected recipient may provide an answer. Stivers and Robinson (2006) examine such cases, and find three pieces of evidence that participants are oriented to a preference for selected recipients of questions to answer: (i) selected speakers routinely begin responding at the transition-relevance place (see Clayman, this volume, on the transition-relevance place); (ii) nonselected recipients, even when they are otherwise able to answer a question, rarely do so at the transition-relevance place; and (iii) nonselected recipients, when they do respond, generally restrict their responses to answers whereas selected recipients also initiate repair or offer I don’t know-type responses. Extract (10) is a case in point. A family is having dinner, and Dad asks his nine-year-old daughter, Cindy, a question about a field trip to a local restaurant that she and her mother went on earlier that day. Cindy is selected as next speaker to answer the question through Dad’s eye gaze and the content.

Having gone on the trip with Cindy, Mom is able to answer the question. However, she refrains from doing so, and it is only after Cindy fails to answer for a substantial amount of time (line 2) and gazes to Mom to pass the turn to her (line 4) that Mom answers for Cindy. Based on this as well as other similar cases, Stivers and Robinson (2006) suggest that interactants are oriented to prioritizing selected recipients to respond, and this preference is relaxed only when progressivity is significantly impeded.

This section has discussed various preferences that questions convey: answer responses are preferred over non-answer responses; affirmation is preferred over disaffirmation; type-conforming answers are preferred over nonconforming answers; answers by selected recipients are preferred over those by nonselected recipients. All these aspects of preferences are mobilized through questions—through their design and the actions they implement.

5 Social Actions Implemented by Questions

We saw in the previous section that questions impose various constraints on answers through their design: they set up agendas, convey presuppositions and impose certain answers as preferred. This protean nature of questions, together with their compelling force to solicit responses (Heritage, 2012a; Steensig & Drew, 2008; Stivers & Rossano, 2010) make them a versatile resource to implement a wide range of other initiating actions than requesting information (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Goody, 1978; Searle, 1969; Steensig & Drew, 2008). Since an action that an utterance implements can be identified only by reference to both its position and its composition (Schegloff, 1984b, 1993), we cannot provide an exhaustive list of actions that questions implement. However, there are some actions that are regularly implemented by questions across languages. This section illustrates how questions implement requests, offers, and criticisms or challenges, and how in these actions question design plays a consequential role.

5.1 Requests

It is well-documented that questions serve as vehicles to implement requests across languages—politer requests than those in the imperative form (e.g. Brown & Levinson, 1978; 1987; Goody, 1978). A research question recurrently asked is when and why one makes a request in the form of a question when other forms (e.g. imperative) are available. Brown and Levinson (1978) suggest that the format of requests reflects the social relationship between a requester and request recipient as well as the nature of the request itself. A polite form is used when the recipient is socially distant from the speaker and/or the imposition a request makes is significant.

Conversation analysts also examine a range of formats to make requests. Through systematic and detailed analyses of spontaneous interaction, they reveal how such notions as social relations or entitlement are negotiated and (re)constructed through turn-by-turn talk. For instance, Lindström (2005) studies Swedish interaction between home-helpers and service recipients and demonstrates that requests in the imperative form convey that the speaker is entitled to having the request granted, while requests in the question form do not. Heinemann (2006) compares requests formatted as positive interrogatives (e.g. Will you please take that … ?) with those in negative interrogatives (e.g. Can’t you turn on the overhead light?) in Danish, and finds that the former conveys that the speaker is not entitled to making the request while the latter conveys that she is entitled. She further reports that the request form is associated with the chances of compliance: requests in the negative interrogative are more likely to receive compliance than those in the positive interrogative. Similarly, Curl and Drew (2008) examine requests in the form Can you X?/Could you do X? in contrast with those prefaced with I wonder if … in English interaction. They demonstrate that the former is used to reflect a speaker’s understanding that his/her request is noncontingent and that s/he is entitled to make the request, while the latter suggests that the speaker sees the request to be contingent and s/he is not necessarily entitled to make it.

As Heinemann (2006: 1101) says, entitlement to requests “is suggested, implied, negotiated and ultimately constituted through the way in which the participants format their contributions.” The variety of question formats is one of the alternative resources for a requesting party to index and mobilize interactional contingencies—who interactants are to each other, what they are entitled to request and whether the request is contingent or not, which may be aligned or disaligned with by request recipients.

5.2 Offers

Offers are another action often formatted as questions. Using telephone conversations in English as data, Curl (2006) reports a systematicity in the offer format and the activity in which the offer is embedded: offers that a caller initiates as the reason for the call are constructed with a conditional clause (e.g. “well if there’s anything you c’n (.) we c’n do: let us know:” (1262)); offers produced as a remedy to the a problem suggested by the interlocutor’s prior talk take the form of questions Do you want (me to) X? (e.g. “well now look d’you want me to come over ’n get her or wha:t” (1268)). Curl suggests that through these alternative constructions, interactants display an orientation to who the agent of these initiating offers is. Here again, question format is deployed to index and negotiate locally relevant identities (i.e. agentive/voluntary offerer vs. unspontaneous, recruited offerer) that participants hold vis-à-vis the matter.

5.3 Criticizing and Challenging

We have seen that a speaker’s K− position is a crucial factor that makes an utterance recognizable as a question. On the other hand, when a speaker holds a K+ position, utterances formatted as questions tend to be recognized as criticisms or challenges. Steensig and Drew (2008: 7) write, “asking a question is not an innocent thing to do; when a question is asked about what its recipient has said or done, it carries a possible implication of disaffiliation.” Indeed, many studies report how questions are used to implement confrontational actions across languages (e.g. Bolden & Robinson, 2010, 2011; Egbert & Vöge, 2008; Heinemann, 2008; Heritage, 2002c; Koshik, 2002a, 2005b).

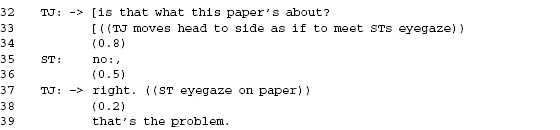

Koshik (2002a, 2005b), for instance, shows that Reversed Polarity Questions (RPQs)—namely questions that convey bias toward the opposite valence than the valence of the sentence—are often used as a means to criticize a student’s performance in pedagogical interaction. For instance, in Extract (11), the teacher’s question “is that what this paper’s about?” (line 32) is produced to actually convey that the student’s paper is not about that.

The teacher’s uptake “right” at line 37 retroactively suggests that the teacher had a ‘correct’ answer in mind when asking the question, and thus, the question was a criticism against what the student had said/written. Koshik (2002a) suggests that RPQs allow teachers to criticize students in a more mitigated manner than explicit criticisms in the form of assertions would.

Similarly, negative interrogatives (e.g. Didn’t you … ?) often serve as positive assertions that challenge the recipient’s position (Heritage, 2002c). This question design is commonly used by journalists to challenge interviewees while formally maintaining ‘neutralistic’ posture (Heritage, 2002c ; Clayman & Heritage, 2002b).

A question need not be biased toward the reversed polarity to convey criticism or challenge. Heinemann (2008), for instance, discusses questions that are ‘unanswerable’—questions that set a context in which both confirming and disconfirming answers would be problematic; confirmation would convey disagreement with the questioner and disconfirmation would require the speaker to contradict what s/he said earlier. She shows in her Danish data that these questions are produced and treated as challenges to the recipient.

Thus, when asked from a K+ position, together with interactional circumstances, questions commonly implement criticisms and challenges. These actions can also be formulated as declaratives (e.g. You shouldn’t have done that.), imperatives (e.g. Don’t do that to me again.) or exclamations (e.g. How dare you!). However, these alternative formulations may sound more confrontational and explicit than questions, and interactants are generally oriented to minimizing such acts.

This section has illustrated a few social actions that questions are commonly used to implement: requests, offers and criticisms/challenges. By formatting these actions as questions, and in questions designed in particular ways, interactants negotiate, and display their orientations to, social and interactional contingencies. Social contingencies managed through question designs are particularly prominent in interactional institution: participants vigilantly attend to their social roles and shape their interactional conduct accordingly. In the next section, we consider how questions and question designs serve their roles in various institutional settings.

6 Questions as Building Blocks of Institutional Activities

When we interact in institutional contexts, participants exhibit orientations to the institutional nature of the situation through their conduct (Heritage, 2003a). In particular, how questions are asked and answered can be remarkably distinctive, indeed constitutive of institutional contexts.

One general feature of question-answer sequences observed across institutional contexts is that questions and answers are pre-allocated to different categories of participants. In many types of institutional interaction—for example medical (see Gill & Roberts, this volume), legal (see Komter, this volume) and in news interviews (see Clayman, this volume)—it is the professional participant who asks questions and the lay participant who answers them. Since, as we have seen in this chapter, questions impose many constraints on answers, lay participants’ conduct is significantly constrained in institutional interaction (Drew & Heritage, 1992a).

Besides this general feature, each institution has its own system and goals of interaction for which question-answer sequences are shaped. For instance, physicians ask patients questions to take medical histories, which play a crucial role in reaching a diagnosis (Stockle & Billings, 1987). And studies report some interactional principles that are specific to medical interaction. For instance, physicians, as a default, design their questions such that they prefer answers that confirm positive, optimistic states (Boyd & Heritage, 2006; Heritage, 2002a): a question Is your father alive? is more common than an alternative way of asking about the same issue Is your father dead?. In contrast, however, in the case of acute care visits, physicians’ questions presuppose a problem with questions such as Are you sick today? or Did you have a fever? (Stivers, 2007b).

In courtroom interaction, too, questions play an essential role, but toward a different objective: attorneys ask plaintiffs and witnesses not to collect information but to make a case to the overhearing audience, namely the jury and/or judge (Drew, 1992). Attorneys are required and constrained to questioning during examination, but they utilize their question turns and third-position turns following answers tactfully in order to build their cases (Drew, 1992; Sidnell, 2010b; see also Komter, this volume).

The orientation to the overhearing audience is significant in news interviews as well: journalists ask public figures questions for the sake of an overhearing audience (see Clayman, this volume, on news interviews). Journalist conduct is bound and motivated by two norms: neutralism and adversarialness (Clayman & Heritage, 2002b). By confining their conduct to questioning, they sustain the “neutralistic posture” (Clayman, 2010c: 262). At the same time, they design questions to be adversarial. For instance, their questions are often preceded by extensive prefaces which allow journalists to provide necessary background information for upcoming questions. These prefaces are often exploited though as opportunities to challenge or criticize interviewees (Clayman, 2010c ; Clayman & Heritage, 2002b). Also, negative interrogatives (Didn’t you … ? and Isn’t it the case … ?), though they take the form of questions, are used and understood as positive assertions that state journalists’ critical positions (Clayman & Heritage, 2002b ; Heritage, 2002c).

In these contexts, as well as in many others that we do not have room to discuss here, questions serve as building blocks for institutional realities. Participants adhere to action types that are allocated to them and design questions to fulfill their institutional identities and roles.

7 Future Directions

This chapter has examined questions in conversation—how utterances come to be recognized as doing questions, how their designs convey various epistemic stances and impose constraints on answers, how they implement other social actions, and how they serve their functions in interactional settings. All of the conversation analytic studies discussed above, through systematic analysis of sequences of spontaneous interaction, contribute to revealing how interactants employ questions and question design to navigate their everyday social life. To conclude the chapter, I discuss some directions for future research.

While question design has been a very fruitful area of inquiry, many research questions await further work. For instance, we know much less about content questions and alternative questions than about polar questions. Functions of prosody in questions are still under-investigated. There may very well be institutional contexts or special interactional circumstances that exhibit peculiar questioning practices that have not been studied.

More significantly, a typology of questioning in interaction is a big research area that needs further research. A large part of the findings discussed in this chapter comes from work based on English data, and there are many studies that report the relevance of these findings in other languages. However, different grammars provide different affordances for asking questions. These can be expected to have interactional consequences, but we know relatively little about them. For instance, among the languages that have particles to mark polar questions, about 15% of them canonically place the particles at the beginning of sentences, while 35% of them do so at the end of sentences (Dryer, 2011a). The relative timing of marking questions is likely to have interactional consequences, and thus poses an interesting research question.

Another example of cross-linguistic variation concerns available lexical distinctions. German has two question words to ask for reasons, wieso and warum (among others). According to Egbert and Vöge (2008), wieso is heard as an information request, while warum is complaint implicative. Many other languages do not have two alternative question words to distinguish these two types of questions, and thus, why-questions allow for potential ambiguity as to whether they are genuine questions or implicit complaints (see Bolden & Robinson, 2011; Robinson & Bolden, 2010). We can expect that speakers of these languages have different considerations and utilities in producing and recognizing the significance of a why-question. Such an interactional phenomena that is not immediately visible in one language due to the lack of a dedicated grammatical resource may be more visible in another language (Heinemann, 2009). The importance of studying interaction in diverse languages cannot be overemphasized. By enlarging the body of literature on the topic, we will achieve a fuller picture of concerns that underlie our interactional conduct.

NOTES

I would like to thank the editors and John Heritage for their comments on earlier drafts of this chapter.

1 These three features—interrogative lexico-morpho syntax, interrogative prosody and recipient-tilted asymmetry—are three of the four features that Stivers and Rossano (2010) call response-mobilizing features. They suggest that question is “an omnibus term that expresses the institutionalization of response mobilization” (Stivers & Rossano, 2010: 29). See Stivers (this volume) and Heritage (2012b, this volume) for discussions on this ‘response-mobilizing’ aspect of questioning.

2 See Stivers and Rossano (2010) and Heritage and Raymond (2012).

3 See section 6 for a further discussion on various forms of questions that implement requests.