24

Storytelling in Conversation

They’re not, then, doing simply telling a story for no good reason, or telling of something that happened once to somebody else, or that happens to people, but they’re offering something that does something now, i.e. describes, explains, accounts for, our current circumstances—mine, yours, or mine and yours.

(Sacks, 1992: II: 465)

1 Introduction

There is a substantial body of literature on storytelling in a number of fields, including Linguistics, Anthropology, Folklore, Sociology, Cultural Studies, Communication, Psychology and Cognitive Science. This work has focused predominantly on the story. In contrast, conversation analytic work focuses on the telling, revealing the stable set of features that interactants deploy to produce storytelling as a recognizable activity and through which they implement a variety of social actions. (On activity and overall structural organization, see Robinson, this volume.) In focusing on the telling of stories, conversation analysts have shown that stories are interactive productions, co-constructed by teller and recipient and tailored to the occasions of their production. The focus on telling also facilitates the observation that with stories, tellers not only relate experiences but simultaneously complain, blame, account, justify and so on (Schegloff, 1997a: 97).

Sacks (1972c: 345) examined the story “the baby cried the mommy picked it up,” explicating the kind of knowledge necessary to understand the story, and to understand it as a story (although a particular kind of story—one told by a child, not the canonical story told in conversation discussed here). He explained that it is recognizable as a story not only

By virtue of being a possible description but also by virtue of its employing, as parts, items which occur in positions that permit one to see that the user may know that stories have such positions, and that there are certain items which when used in them are satisfactory incumbents.

(Sacks, 1972c)

In this way, Sacks introduced a fundamental question that he would later discuss in more detail and which we will consider in this chapter: what makes a story recognizable as a story to recipients and to analysts? This question takes on more significance when we realize that the telling of a story usually requires extended turns-at-talk on the part of the teller, and a passing up of the opportunity to take turns, on the part of the recipient—a suspension of the ordinary turn-taking arrangement of conversation that guarantees a speaker only one turn-constructional unit of talk (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974; see Clayman, this volume, on turn-taking). Yet, this can only be achieved if there is recognition, at the beginning of the story’s telling, that it is, in fact, a telling.

In this chapter I describe the distinctive features of storytelling. I show how interactants work together to suspend turn-by-turn talk so that the teller can produce an extended turn-at-talk. I describe how prospective tellers make available the connection between their telling and the talk that precedes and follows it. I further show how tellers convey their stance toward the events they report and how recipients, through verbal and embodied responses, respond to such conveyed stances while the story is being told and at its conclusion (on embodiment, see Heath & Luff, this volume). How a storytelling is actually composed is complicated by what the teller assumes or knows the recipient(s) to know, and also by how many recipients are present. I discuss how tellers and recipients manage these exigencies. Lastly, I show how stories are constructed to accomplish particular actions in both everyday and institutional settings, and consider the various tasks that stories may be used to implement.

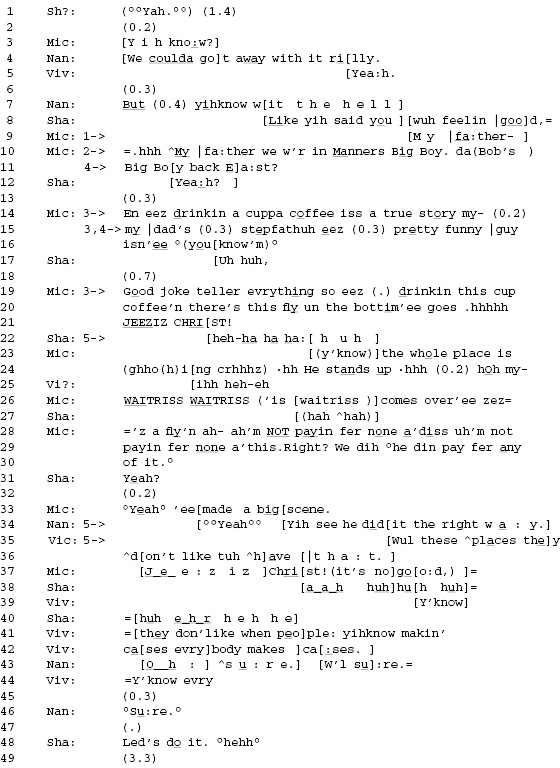

My discussion of one story provides a basis for this examination of some of the key features of storytelling in everyday interaction. It occurs during a dinner shared by two couples, Shane and Vivian, and Michael and Nancy. Immediately prior to the telling, prompted by Nancy’s joking suggestion to Michael that he “check the food for bugs,” the group has been discussing how they could have gotten away without paying for their dinner and drinks the night before because of a problem with the food.

The matter seems to be coming to a close as Nancy, in line 7 below dismisses the discussion with “But (0.4) yihknow wit the hell”. While Shane in line 8 reiterates a point made earlier in the talk, that their mood at the time explains them not trying harder to get out of paying for the meal, Michael, just where Nancy’s apparent dismissal of the matter comes to a point of possible completion, introduces to the conversation a new person: “My |fa:ther”. Examine Extract (1) for how:

Below I discuss each of these, showing what we can learn by focusing on the telling itself.

This brief story provides a basis for our consideration of the interactive work tellers and recipients engage in to launch a storytelling, provide proper resources for recipients to understand it, formulate its upshot, and reengage turn-by-turn talk upon its completion, deploying interactional resources in such a way as to implement action while managing this complex set of interactional contingencies.

2 Storytelling and Turn-by-Turn Talk

Because interactants build conversations turn-constructional unit by turn-constructional unit, typically each speaker is entitled to one TCU at a time, and at its point of possible completion, another speaker may begin to talk (cf. Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974; see also Clayman, this volume). Using the resources of prosody, grammar and pragmatics, interactants project the point of possible completion of a current unit of talk in order to determine when they may begin a next turn (Lerner, 2004a; Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974). In contrast, telling a story usually involves recounting events that require more than one turn-constructional unit to tell.1

Sacks (1992: II: 21) notes that, “The issue of the production of a story might involve that anybody’s determining that it is a story is relevant to its coming off as a story.” That is, the telling of a story is a distinctive and identifiable form of talk. In principle, the story needs to be recognized by recipients as a story before the end of the first possible turn-constructional unit, if the teller is to be able to continue the telling. The question is how they build the first TCU to be recognizable as launching a telling.

3 How Prospective Tellers Launch Storytellings

Storytellings can be initiated in first position, by the prospective teller, as occurs in The Fly in the Coffee story in Extract (1). Here, just as Nancy completes a turn in line 7 in which she wraps up talk about their previous evening with “yihknow wit the hell”, Michael refers to a person who has not been mentioned so far: “My |fa:ther” in line 9 (referred to again in line 10 after the overlap is resolved). This initially presents recipients with a puzzle as to the relevance here of this person. However as he proceeds, he provides details of a location: “we w’r in Manners Big Boy.” At this point it may become recognizable that Michael will have more to say about his father and what transpired in this location. Given immediately prior talk about the participants’ bad experience in a restaurant, recipients might also infer a connection of some sort to that restaurant location, although this is not made available explicitly.2 Recipients must do some work both to determine that there may be a story to tell, and to understand what its relevance might be here. In line 13, Shane, a prospective story recipient, apparently acknowledges the place reference with “Yea:h?”. Importantly, in line 13, there is a gap after the possible completion of Michael’s turn. The fact that no one begins talking provides some evidence (for both us and Michael) that fellow interactants are treating Michael’s turn as one that will continue, and indeed, in line 14, Michael begins to recount something his father was doing: “En eez drinkin a cuppa coffee”. Thus his turn evolves into a recognizable storytelling format: the recounting of a past event. This suggests that one way to launch a storytelling is simply to begin, relying on recipient ability to recognize an incipient storytelling.

The beginning of The Fly in the Coffee storytelling contrasts with beginnings in which prospective storytellers secure recipient alignment to a storytelling in advance of beginning it. This can be done by using a first-pair part request or offer (such as, “W’ll why’on’ I change thuh subject an’ tell ya about thuh wedding.”, or, projecting a joke, “You wanna hear a story my sister told me last night”; Sacks, 1978: 250). Projecting a storytelling in this way puts prospective recipients in a position to forward or block the storytelling. In addition to the prospective teller indicating, through the story projection or story preface (Sacks, 1974a, 1974b, 1978), that there is something to tell (making relevant the suspension of regular turn-by-turn talk in order to produce a multi-unit turn), in this turn the teller also makes available various possible aspects of the nature of the incipient telling (e.g. the source of the story, that it was recent—Last night … , etc.), providing resources for prospective recipients to align as recipients of an upcoming extended turn, and to project what kind(s) of responses will be relevant to the story and when, not only while it is in progress, but also upon completion.

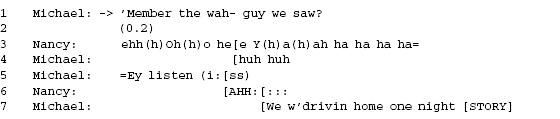

One type of story preface is to solicit the recollection of an occurrence shared with another co-participant. Lerner (1992) describes reminiscence recognition solicits, as occurs in the following extract:

Here Michael addresses his talk to Nancy, but makes it available for the other non-addressed recipients (Lerner, 1992: 255), putting them in the position to infer that there may be something Michael and Nancy could report. Nancy’s turn at line 3, “Oh yah”, with laughter incorporated into it, both claims to remember the guy that they saw, but also, through the use of laughter, indicates the character of the event Michael has invited her to recall, making available to prospective recipients that something funny may be coming up.

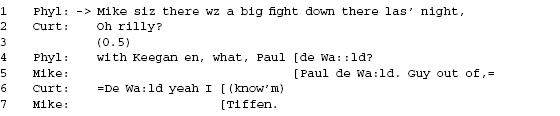

Sometimes someone who already knows a story will prompt the prospective teller (who knows the story firsthand (cf. Sacks, 1984b, on entitlement to experience)) to tell it (Lerner, 1992), effectively delivering the story preface and securing a story recipient, as occurs in the following instance (also discussed by C. Goodwin, 1986a, 1987b; Schegloff, 1987a, 1988a, 1989):

With Mike present, Phyllis reports something Mike told her. Curt’s “Oh rilly?” in line 2 could make relevant further telling about the event, since he shows interest or surprise. When Mike does not begin to tell in line 3, Phyllis extends her turn, introducing a main character and seeking Mike’s help in identifying another main character. In this way, Mike is prompted to tell the story by a knowing recipient, but one who indicates that the story is Mike’s to tell, not hers, thus making relevant Mike’s telling of the event (Lerner, 1991: 251–3).

In contrast to stories initiated in first position by the prospective teller, some stories are produced in second position, responsive to something prior. For example, they may be initiated through an inquiry, invitation or solicitation (Schegloff, 1997a: 103; Sidnell, 2010a: 180). For instance, in the process of discussing an upcoming outing to see a play, the story of which is known to Hyla, Nancy asks, “Kinyih tell me what it’s abou:t?” and Hyla proceeds to tell her. Lerner (1992) describes various ways in which story beginnings are coproduced by story consociates, thus building a story from its beginning as known by more than one participant. This is one way of managing the problem of having recipients with different states of knowledge about the event to be recounted, since the knowing recipient is acknowledged from the outset (cf. C. Goodwin, 1979, for an account of how recipients’ differing states of knowledge are oriented to in the production of a single sentence).

Whether they are initiated in first position or second position, by the prospective teller, or by a knowing or unknowing prospective recipient, interactants deploy a range of practices to secure the floor for an extended turn-at-talk, indicating both that there may be a story to tell, and what might constitute proper responses to it.

4 How Tellers Shape Recipient Response

Tellers provide recipients with a variety of indications of what is important in the telling and how they should react to the telling. These indications may be in the story preface or at the beginning of the telling with elaboration throughout the telling. In Extract (1), immediately after referring to “∧My |fa:ther” in line 10 of the Fly in the Coffee story, Michael suspends the forward progress of the turn about his father and introduces a location, inserting himself and others (inferrably including his father) into it: “we w’r in Manners Big Boy. da(Bob’s ) Big Boy back Ea:st?” In reformulating the place reference from Manners Big Boy, he indicates attentiveness to what his recipients are able to recognize. It is possible that through the shift from “Manners” Big Boy (found only in Northeastern Ohio) to “Bob’s” Big Boy found both on the West coast (where interactants are currently located) and the East coast (where Shane and Vivian are from), Michael indicates that the location of the event he is about to recount is important. This provides a resource for recipients in further determining the nature of the story. While features such as the location of events may not always be central to a story’s telling, Sacks (1974b: 134) describes how a location reference can provide information relevant to figuring out what is going on in the events of the storytelling. Providing the location of the event as a restaurant, albeit a casual hamburger place, suggests that this is consequential for understanding the events to be related—in this case, the success in securing a free meal due to Michael’s father’s behavior.

We also see early indications of the type of stance recipients should take in Extract (1). After reporting an action his father was taking “En eez drinkin a cuppa coffee”, Michael suspends the forward progress of the story. In a parenthetical segment (C. Goodwin, 1984: 236) he offers a characterization of the story he is about to tell: “iss a true story”. In claiming that the story is true, he makes available to recipients that the upcoming story may be so surprising that they may take it to be untrue. Michael then offers a characterization of the person with whom he began the storytelling, his father: “my |dad’s (0.3) stepfathuh eez (0.3) pretty funny |guy isn’ee °(you know’m)°”.3 Shane’s gaze is directed at his food at that moment, but he produces an “Uh huh” in line 17, acknowledging Michael’s characterization of his father as a “pretty funny |guy”, (even though it was addressed to Nancy). This indicates that Shane is aligned as recipient of Michael’s ongoing turn in that he works to facilitate the progression of the telling. Apparently in response to the “isn’ee” in line 16, Shane looks over at Michael. In response to this, Michael continues with an additional characterization of his father: “Good joke teller everything”. Both the characterization of the father as a pretty funny guy and the characterization of him as a good joke teller provide additional information that the telling still to come will be (and should be taken to be) humorous.

Here then we see how, in the particulars of the construction of the storytelling—specifically how it is proposed and begun—tellers convey their “affective treatment of the events” they are recounting, or their stance toward them (Stivers, 2008: 27). As Stivers notes, this may or may not be communicated explicitly. While it is possible for the teller to report events neutrally—namely not conveying a stance toward them—usually in the construction of the telling, various components make available how the teller feels about the events. The teller’s stance, and the extent to which this is conveyed, is a crucial resource for recipients, as it makes available the teller’s expectations regarding how the events of the storytelling are to be responded to.

5 How Recipients Respond to Storytellings

Just as recipients of jokes must monitor for the punch line so that they can respond in the right way at the right time (Sacks, 1978), storytelling recipients must monitor for the possible climax of the story so that they can produce a proper response. They draw on the story’s sequential context (that is, the character of preceding talk), its beginning or preface, and background material provided by the teller, as resources for ascertaining what event could constitute the climax of the story.

Finding a fly in one’s coffee could be heard to be a situation that is directly related to the group’s experience discussed immediately preceding The Fly in the Coffee story. It might therefore be inferable that the point of Michael’s story could be to report to recipients what his father did in a similar situation that resulted in him not having to pay (in contrast to what they had done the previous night that resulted in them having to pay). However the build-up of his father as a funny guy and good joke-teller apparently leads recipients to monitor the telling for something that bears that out instead. So when Michael enacts his father’s extreme response (“JEEZIZ CHRIST”, line 21), recipients (notably Shane) erupt in the kind of laughter the climax of a story billed as funny could relevantly elicit. It would appear that Michael’s way of introducing the main character has made relevant for response a different element than getting away without paying after making a fuss about a problem with the food. That the story may in fact have been headed toward making the point that this is the kind of thing one needs to do to get away without paying (as opposed to being simply a report of his father’s amusing and over-the-top reaction) is indicated in the ‘retrofit’ that Michael engages in in subsequent utterances, particularly lines 28–30 and 33. Jefferson (1979) showed that laughter is normatively responded to with laughter, but in line 23 Michael continues his storytelling. This indicates that the telling is not complete at this point. He continues the telling by recounting how his father called for a waitress, reported the fly in the coffee, and announced, “ah’m NOT payin fer none a’diss uh’m not payin fer none a’this.” In reporting what his father actually said, recipients may recall that immediately prior to this segment, when the group was discussing what they could have done when facing a situation in which they had a problem in a restaurant, Michael used almost these exact words: “Yih know what I should a said was look ah’m not payin for it.” Thus through reported speech (Holt, 2000), Michael provides a resource—albeit tacitly—for recipients to connect this story with their experience the previous night.

In lines 29–30 Michael formulates the upshot of the reported event: “We din pay fer any of it.” but Shane does not treat this as the possible completion of the storytelling. Rather, he produces a minimal, questioning “Yeah?” which Michael confirms with “°Yeah°” before formulating the upshot again: “’ee made a big scene.”, thus recompleting the story, providing another opportunity for recipients to respond. Nancy’s response in line 34 formulates what Michael may have been going for all along: “Yih see he did it the right wa:y.”, thus making it available that she hears what Michael reported his father to have done as being offered as a contrast to what the group did the previous night (which was, inferably, the ‘wrong’ way).

Here both how the teller sets up the story, and how recipients respond to it, shape what the storytelling amounts to. Stivers (2008) notes that recipients may enact a particular orientation toward the storytelling in two distinct ways: alignment and affiliation (see also Lindström & Sorjonen, this volume). Alignment concerns the orientation that a recipient takes up with regard to the current state of talk, treating it as a storytelling by showing an understanding that there has been an adjustment of the turn-taking arrangement to accommodate one party taking an extended turn-at-talk, with minimal contributions from the recipient(s), until the storytelling is possibly complete. Interactants enact alignment as recipients of a storytelling by, for instance, forwarding the telling after a prospective teller has projected that there may be something to tell, and producing continuers or assessments (see below) as the story is told. That is, the recipient “supports the structural asymmetry of the storytelling activity” (Stivers, 2008: 34), co-participating in a rearrangement of the canonical organization for everyday talk in interaction, where (as discussed above) one speaker takes one turn-constructional unit and then speaker transition occurs (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974). A speaker who is aligned as recipient of an ongoing storytelling usually enacts this alignment by producing talk that is hearably relevant at the possible end of a unit of the ongoing story, and does not launch or participate in a competing action. Thus the recipient’s enactment of alignment to the asymmetrical arrangement of talk, and attention to the sequential implications for recipient contributions of an ongoing storytelling, are key components in the interactive constitution of the storytelling.

In responding to storytellings, recipients may adopt the teller’s stance toward the events, or resist it. Endorsing and/or displaying support of the teller’s perspective constitutes affiliation (Stivers, 2008: 35). In The Fly in the Coffee story, Michael builds the story to be hearable as funny. Shane’s strong laughter in response to what he takes to be the punch line of the story may be understood as an affiliative response. Nancy’s response at the end of the storytelling is strongly affiliative with the stance Michael has provided through the storytelling with regard to what they should have done at the restaurant the previous night. Although we saw in The Fly in the Coffee story that Michael may have inadvertently provided for recipients to treat the story as funny by how he introduced the protagonist, there are occasions when recipients resist the teller’s overt stance toward the events being recounted. Mandelbaum (1991) described different ways in which recipients resist the complaining action a storytelling is designed to implement, extracting and responding to other storytelling elements as a way of resisting affiliating with a complaint. Recipient resistance to the teller’s stance in some storytellings indicates that recipients are strongly attuned to the action a teller may be designing a story to accomplish, and the potential (and sometimes complex) relational consequences of their affiliation with it.

Our discussion so far shows how, in the course of an ongoing storytelling, recipient responses are crucial to the development of the telling. While traditional approaches to storytelling have tended to view the recipient as a passive ‘audience member’, whose contributions to the story’s telling are minimal (and may not be incorporated in the discussion or even the transcript of the storytelling), conversation analytic work shows that the ‘audience’ is in fact the co-author (Duranti & Brenneis, 1986), with recipient turns playing a crucial role in shaping and even constituting the ongoing course of the storytelling. Research suggests that recipient responses can be arrayed on a continuum from passive to active, according to the extent to which they make relevant a specific response from the teller, and thus constrain what the storyteller can do next in a continuing storytelling. Some recipient responses (such as continuers like mm hm, uh huh or head nods) may be characterized as ‘passive’ in the sense that, for the most part, they do not put the teller in the position of having to shape the storytelling in response to them (Drummond & Hopper, 1993a; C. Goodwin, 1986b; Schegloff, 1982). Others such as assessments (e.g. Oh wow or God) provide an indication of the recipient’s understanding of the telling (Goodwin, 1986b), and may thus make it relevant for the teller to respond to the recipient’s response, for example by adjusting the details of the story to clarify how the story should be taken. Some recipient responses (such as questions) are first-pair parts that make relevant particular kinds of responses from tellers, and may thus serve to divert or redirect an ongoing storytelling (Mandelbaum, 1989).

6 Recipient Responses via Body Behavior

As in all face-to-face interaction, in storytelling deployment of the body by both speaker and recipient is carefully attended to. C. Goodwin (1984) showed how such aspects of body behavior as gaze, facial displays and body orientation are integral parts of the telling of a story. Goodwin (1984: 231) noted that while in regular turn-by-turn talk, the addressee should be gazing at the speaker (cf. also C. Goodwin, 1981), a storytelling environment seems to make relevant different practices regarding eye gaze between speaker and recipient (see also Rossano, this volume, on gaze). He showed how if an interactant has aligned as recipient during the preface of a storytelling, he or she may direct his or her gaze elsewhere during a background segment (1984: 130–1). This is evident in The Fly in the Coffee story, as Shane and Vivian, the unknowing recipients, gaze at Michael while he is beginning the story, attend to their food once the storytelling appears to be under way, and look back at Michael when response may be relevant (e.g. after the place reference in line 11, and at the possible punch line in line 22). Looking away at this specific point is a way of enacting an orientation to the storytelling as an ongoing unit of talk that will continue, as gaze could be taken to indicate that the recipient takes it that speaker transition could or should occur at the next point of possible turn completion. Goodwin further showed that despite orienting to such concurrent activities as eating, recipients of an ongoing storytelling may show that they are nonetheless attending and oriented to the storytelling by producing a nod, for instance. Kidwell (1997) showed that gaze may be an important resource by which a non-addressed story recipient seeks to be included as an addressed recipient.

Sidnell (2006) examined reenactments during storytellings, distinguishing between reenactments, direct quotation, and demonstration. Holt (2000: 249) suggested that direct reported speech “can be said to ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ the recipient what was said and in doing so it gives them ‘access’ to it.” Sidnell (2006: 381) suggested that reenactments are like direct reported speech and demonstrations, “in that they depict or show rather than describe.” He noted that during the description of events, tellers typically gaze at recipients while recipients’ gaze may be directed elsewhere (as C. Goodwin, 1986a, also notes). In contrast, during reenactments (such as reenacting driving a car), tellers often gaze directly in front of them (or in some other direction) and not at recipients since the gaze direction is actually part of what is being reenacted, while recipients gaze directly at tellers. Sidnell observed that in ending reenactments, the return of the teller’s gaze to recipients can be a crucial resource for recipients to recognize the shift from enactment to narration (392).

Stivers (2008) described how one place where head nods are recurrently produced by recipients in the course of an ongoing storytelling is when tellers provide more direct access to the telling through, for instance, direct reported speech. The nod can serve as a preliminary indication of affiliation with the story. This further emphasizes the importance of continuers to the ongoing storytelling, and suggests the nuances available to recipients even in a response form that may seem ‘passive’ in terms of its impact on the course of the storytelling.4

7 Recipient Disruption of Storytelling

As we have seen, central to the production of a storytelling is recipient collaboration. While, as noted above, there are a number of ways in which recipients produce talk in the course of an ongoing storytelling in such a way as to support the activity of storytelling, and possibly also the action that the teller is building through the storytelling, there are also many ways in which recipients may intervene (M. H. Goodwin, 1997; Lerner, 1992; Mandelbaum, 2010) into an ongoing storytelling. There are occasions in which a recipient exploits the fact that the teller’s ability to tell a story is contingent on recipient co-participation, by participating in ways that may derail or divert the storytelling. Responses other than continuers or affiliative assessments may have serious disruptive consequences for the progressive realization of the storytelling. For instance M. H. Goodwin (1997: 79) shows that “playful commentary” about talk in progress can embellish the storytelling, but “repair-like moves that critique the speaker’s talk” may prompt the teller to close the telling down. Some recipient turns are fatally disruptive of storytelling alignment between conversation participants. Initiators of byplay also carefully position it and produce it in ways that “minimize its intrusiveness” (99). Goodwin shows how byplay can be momentary, or more extensive, and how this is arrived at interactively by teller and recipients.

In addition to “heckling” (Monzoni & Drew, 2009; Sacks, 1992: II: 284–8), Mandelbaum (1991) notes that storytellings may be derailed when taking up a teller’s project implemented through the storytelling would conflict with other constraints on the recipient’s responses. For instance, in taking up a teller’s complaint, a recipient might risk co-complaining about someone. Recipient-led disruptions of storytellings indicate again the interactive character of storytelling, and also the interactive character of what a storytelling comes to be “about.” However, in her description of “byplay,” M. H. Goodwin (1997: 98–9) notes that tellers deploy various resources to prevent byplay from becoming the primary focus instead of the storytelling. And, as Mandelbaum (1993) noted, tracking the development of a storytelling provides insight into practices through which ‘reality’ is interactively constructed and reconstructed.

8 How Tellers Use Storytellings to Produce Actions

Studies of storytelling have shown how stories may be designed to implement a range of actions (on action, see Levinson, this volume). For instance, they may make fun of someone, often a co-present recipient (C. Goodwin, 1984; Mandelbaum, 1987, 1989), complain (Drew, 1998; Mandelbaum, 1991; Monzoni & Drew, 2009; Schegloff, 2005a), account for conduct (Buttny, 1993; Mandelbaum, 1993), or recount troubles (Cohen, 1999; Jefferson, 1980a, 1980b, 1988, 1993; Jefferson & Lee, 1992). Jefferson (1988) described a robust series of interactional moves by a prospective troubles teller and troubles recipient for producing troubles-tellings that are, in fact, rarely implemented in their entirety, probably due to their sensitivity to local interactional contingencies. This reinforces the tight connection between how a story is structured, the action it is produced to implement, and the interactional character of that implementation, in which teller and recipient work together rather than a telling being produced as a teller’s monologue (Schegloff, 1997a). Further Jefferson (1988) shows how, in the course of the unfolding trajectory of a troubles-telling, speakers may move from distance to intimacy as the recipient takes up the trouble and responds to the troubles-telling in an affiliative way. Recipients’ affiliative responses may foster further elaboration of the troubles-telling.

As I discuss above regarding recipient responses, while recipients initially treat The Fly in The Coffee story as about something funny that Michael’s father did, in the rest of the story we see Michael working to shift what recipients make of the storytelling. It becomes clear that his story is designed to provide an exemplar of what one could do when faced with a “bug” in one’s food, hearably contrastive with what the group did the night before. It emerges that he is not designing his story merely to entertain his recipients, and when it appears to be the entertaining aspect of it that they are attending to, he works to shift their understanding. In turn, recipients revise what they make of the telling. In the large, multi-disciplinary literature on narrative, it is often assumed that what a story is designed to accomplish (what Labov, 1972a: 366–75, characterized as “evaluation”) is constructed and implemented solely by the teller. As M. H. Goodwin (1997: 77) points out though, and as our discussion above indicates, what a story comes to be about is usually arrived at through the interaction between teller and recipient.

While many stories are told in such a way as to be entertaining, like The Fly in The Coffee story, all stories in conversation appear to be both designed by tellers and understood by recipients to be doing something. Sacks (1978) pointed out that even the telling of a joke, a canonical case of a story-like structure used to entertain, is designed to implement important ‘social work’—addressing for and transmitting to its intended audience, norms and concerns about their everyday social worlds, for instance. Stories appear to be deployed to implement a variety of tasks. In institutional settings, this may be yet clearer. For instance, patients sometimes use a storytelling format to present the history of the problem that brings them in to the doctor’s office (Halkowski, 2006; Heritage & Robinson, 2006a). Narrative expansions emerging from patients’ answers to physicians’ questions provide a window into the lifeworld of the patient. Physicians must make delicate choices in determining whether and how to take up patients’ narratives (Beach & Mandelbaum, 2005; Stivers & Heritage, 2001; on CA work on medical interaction, see Gill & Roberts, this volume).

Thus we see that storytelling is deployed to implement a wide range of actions in both informal and institutional settings. Much of the work on storytelling in everyday conversation indicates that and how stories are designed to implement actions, and that recipient responses during the storytelling and at its possible end co-participate in constructing what the attempted action actually amounts to.

9 How Tellers end Storytellings

In turn-by-turn talk, interactants project the possible end of a turn-constructional unit using prosody, grammar and pragmatics (Ford & Thompson, 1996; Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974; see Clayman, this volume, on turn-taking and the transition-relevance place). In order for the possible end of a storytelling to be recognized, making relevant recipient uptake of the story and a return to turn-by-turn talk, tellers must construct the ending of the storytelling as an ending. A canonical way of producing a recognizable story ending is, as Jefferson (1978: 231) points out, to “return home.” For instance, in a telling that begins at a pizza place, involving a trip away from it, a return home “’n were back t’ the pizza joint we started from” (Jefferson, 1978: 230) works to indicate to the story recipient that the telling is complete.

In the ending of the telling, a teller may provide an utterance that demonstrates how the storytelling makes relevant further topical talk. If recipients talk by reference to this, then reengagement of turn-by-turn talk will result (Jefferson, 1978). However, recipients do not always take up the possible end of a storytelling right away, and tellers then need to engage in pursuit of recipient uptake, as occurs in The Fly in the Coffee story in line 33. Jefferson showed how a teller can use story components to expand the telling as a kind of exit device. Producing further talk by reference to the story, or recycling elements of the story, ‘recompletes’ it, making available another opportunity for recipients to respond to it after initial lack of uptake. An example of this occurs in The Fly in the Coffee story when Michael recompletes with “’ee made a big scene.” to indicate the upshot of his telling after it was taken up only minimally by Shane with his “Yeah?” in line 31.

The ending of a storytelling is interactionally arrived at; it is not enough for the teller simply to present the story as possibly complete. Recipients must treat it as complete, by producing a turn that indicates that they take the story to be possibly complete, such as providing their understanding of the story’s implications.

In addition to the reengagement of turn-by-turn talk, tellers may orient to what recipients are making of the story, and thus what the story has amounted to (Jefferson, 1978: 233). Recipients may rely on indications from the teller at the beginning of the storytelling, or from indications provided as the story progresses, as to what they should make of the storytelling, as we saw in The Fly in the Coffee story when Michael, at story completion says “We dih °he din pay fer any of it.°” (lines 29–30).

Another way in which recipients indicate what they are making of a storytelling is by telling a “second” story (Ryave, 1978; Sacks, 1992: I: 764–72, II: 3–17, 249–68). These stories are built to show that they are touched off by and/or are picking up the point of the story to which they are responding (Sacks, 1992: I: 767–8). Sacks also noted that second stories are not just “touched off by,” but are carefully fitted to and specifically “stand as analysis of” the prior (771).

10 Future Directions

As this discussion indicates, a substantial body of work exists on the organization and interactional uses of storytelling in interaction, showing how challenges inherent in telling a story are resolved by teller and recipient working together, using storytelling to produce a variety of actions. This accumulation of knowledge, in addition to the many advances in our understanding of a variety of domains of the organization of interaction, provides for opening new frontiers in our explorations of storytelling. Nonetheless, many aspects of storytelling require further exploration, including the variety of ways in which stories are begun and ended, how characters are introduced into a storytelling, how recipients figure out what they should or could be making of a storytelling, and how storytelling practices are used in institutional settings.

While Jefferson (1978) has described how stories are triggered or systematically introduced into talk, work remains to be done to describe the variety of contexts from which stories emerge—what makes them relevant and what prompts prospective tellers to tell them? We know less about stories begun in the way that The Fly in the Coffee story above begins—with a teller simply launching the telling—than we do about those that are systematically introduced or overtly projected with a preface. Further work is needed on stories begun with pregnant turns such as Shane ate lobster this afternoon (Mandelbaum, 1989), and other such turns in which a prospective teller projects a story without actively forcing recipients into recipient position with an initiating action. Rather, these turns make available possible news for further expansion, if they are taken up. The relationship between how a story is projected (i.e. what the projection makes available about what the story is designed to do) and how it is taken up by recipients should also be examined. The matter of a story’s ‘stability’—whether or not turn-by-turn talk is resumed before the story is completed, or the story is in some way interrupted or diverted—may also be related to how the story is begun. Additionally, further work examining stories that are projected but are not forwarded may shed light on how and why some projected stories are taken up, while other are not.

Further investigation of membership categorization practices in storytelling (e.g. when a character is introduced into a storytelling) will provide for further exploration of this important domain. Different genres of storytelling provide further interesting access to this issue. For instance, reminiscences produced in story format call on recipient (or possible co-teller) knowledge in particular kinds of ways. Collaboration with and resistance to co-telling or affiliating with the upshot of reminiscences have implications for family and other relationships (Mandelbaum, 2010), and offer fertile ground for further investigation.

While some work has examined what may happen when a recipient takes up a different aspect of the story than the one projected by the teller (Jefferson, 1978; Mandelbaum, 1989, 1991, 1993), further work remains to be done on the endings of stories and the different practices tellers and recipients deploy in managing the production of a story ending, the uptake of the story, and the resumption of turn-by-turn talk.

Further study of storytelling in institutional settings may enable us to lay out additional distinctions between these storytellings and those told in everyday noninstitutional settings. It is likely that the particular practices used to tell stories in institutional settings contribute to the constitution of the setting as an institutional one (Drew & Heritage, 1992a).

In addition to laying out the practices through which tellers and recipients work together to produce a storytelling, and thereby produce a variety of actions, CA work on storytelling both benefits from and contributes to lines of work on sequence organization (see Stivers, this volume)—by showing how storytellings are recognized and oriented-to as distinctive structures that shape action while they are under way, thereby constituting a different sort of sequence organization than the adjacency pair, but one that nonetheless makes relevant particular kinds of action; membership categorization and reference—by examining, for instance, the knowledge deployed in introducing events and characters; and turn-taking—by examining the distribution, deployment and management of multi-unit turns, for example. In focusing on the practices of telling, rather than on the story, CA work has elucidated significantly our knowledge of this important domain of action.

NOTES

The author is grateful to Gene Lerner and Manny Schegloff for very helpful discussion at the inception of this chapter, and to Gene Lerner for important insights during its development. The editors of this volume provided invaluable suggestions.

1 While here our focus is storytelling, extended turns are used to implement a variety of activities in addition to storytelling. These include responses to questions in sociolinguistic interviews (Labov & Waletzky, 1967), giving directions (Psathas, 1979a), updating (Drew & Chilton, 2000; Morrison, 1997), announcing news (Maynard, 2003; Terasaki, 2004), making lists (Jefferson, 1991; Lerner, 1994), giving instructions, dictating recipes, etc.). Multiunit turns may also be one way in which other actions such as defending oneself against a possible complaint or accusation (Schegloff, 1980: 117–20, 128–31; Schegloff, 1988a: 118–31) may be implemented.

2 Jefferson (1978: 224) notes that speakers may also use practices that make apparent the connection between a storytelling and the prior talk from which it emerges or is touched off, and that those ways of introducing a storytelling have consequences for how the story itself unfolds, and how it is responded to.

3 It is possible that when he is addressing Nancy he is ‘reminding’ her of a characteristic of his Dad, but in addressing Shane he provides him with ‘new’ information (cf. C. Goodwin, 1979, regarding how a speaker may shift an utterance in its course in response to particular recipients).

4 The recognizability of continuers such as mm hm, yeah, head nods, etc., as indicating the recipient’s understanding that a telling will continue is demonstrated when a recipient produces a continuer at the possible end of a storytelling, and a teller treats it as displaying the recipient’s understanding that the telling is not in fact complete, necessitating, for example, recompletion of the storytelling (cf. Schegloff, 1982: 84).