Chapter 7

U.S. Treasury Securities

Frank J. Fabozzi, Ph.D., CFA

Adjunct Professor of Finance School of Management Yale University

Michael J. Fleming, Ph.D.*

Senior Economist Federal Reserve Bank of New York

United States Treasury securities are direct obligations of the U.S. government issued by the Department of the Treasury. They are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and are therefore considered to be free of credit risk. Issuance to pay off maturing debt and raise needed cash has created a stock of marketable Treasuries that totaled $2.8 trillion on June 30, 2001.1 Treasuries trade in a highly liquid round-the-clock secondary market with high levels of trading activity and narrow bid-ask spreads. Despite the absence of credit risk and the high level of liquidity, an investor in a Treasury security is still subject to interest rate risk and non-U.S. investors who seek to convert payments from U.S. dollars to their local currency are exposed to currency risk. As will be explained, there are Treasury securities that are available that eliminate inflation risk and reinvestment risk.

Treasury securities serve several important purposes in financial markets. Due to their liquidity and well-developed derivatives markets, Treasuries are used extensively to price, as well as hedge positions in, other fixed-income securities. Exemption of interest income from state and local taxes also helps make Treasuries a popular investment asset to institutions and individuals. Moreover, by virtue of their creditworthiness and vast supply, Treasuries are a key reserve asset of central banks and other financial institutions.

TYPES OF SECURITIES

Treasuries are issued as either discount or coupon securities. Discount securities pay a fixed amount at maturity, called face value or par value, with no intervening interest payments. Discount securities are so called because they are issued at a price below face value with the return to the investor being the difference between the face value and the issue price. Coupon securities are issued with a stated rate of interest, pay interest every six months, and are redeemed at par value (or principal value) at maturity. Coupon securities are issued at a price close to par value with the return to the investor being primarily the coupon payments received over the security’s life.

The Treasury issues securities with original maturities of one year or less as discount securities. These securities are called Treasury bills. The Treasury currently issues bills with original maturities of 13 weeks (3 months) and 26 weeks (6 months), as well as cash-management bills with various maturities. The Treasury announced in July 2001 that it would start issuing bills with 4-week maturities. On June 30, 2001, Treasury bills accounted for $620 billion (22%) of the $2.8 trillion in outstanding marketable Treasury securities. Because their maturity is less than one year, Treasury bills are viewed as part of the money market and were discussed in Chapter 6.

Securities with original maturities of more than 1 year are issued as coupon securities. Coupon securities with original maturities of more than 1 year but not more than 10 years are called Treasury notes. Coupon securities with original maturities of more than 10 years are called Treasury bonds. The Treasury currently issues notes with maturities of 2 years, 5 years, and 10 years. In October 2001, the Treasury suspended issuance of 30-year Treasury bonds. While a few issues of the outstanding bonds are callable, the Treasury has not issued new callable Treasury securities since 1984. On June 30, 2001 Treasury notes accounted for $1.5 trillion (52%) of the outstanding marketable Treasury securities and Treasury bonds accounted for $617 billion (22%).

In January 1997, the Treasury began selling inflation-indexed securities. The principal of these securities is adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index for urban consumers. Semiannual interest payments are a fixed percentage of the inflation-adjusted principal and the inflation-adjusted principal is paid at maturity. On June 30, 2001, Treasury inflation-indexed notes and bonds accounted for $129 billion (5%) of the outstanding marketable Treasury securities. As these securities are discussed in detail in Chapter 8, the remainder of this chapter focuses on nominal (or fixed-rate) Treasuries.

THE PRIMARY MARKET

Marketable Treasuries are sold in the primary market through sealed-bid, single-price (or uniform price) auctions. Each auction is announced several days in advance by means of a Treasury Department press release or press conference. The announcement provides details of the offering, including the offering amount and the term and type of security being offered, and describes some of the auction rules and procedures. Exhibit 7.1 shows the August 1, 2001 announcement by the Department of the Treasury of the August 2001 auctioning of a 10-year note.

Treasury auctions are open to all entities. Bids must be made in multiples of $1,000 (with a $1,000 minimum) and submitted to a Federal Reserve Bank (or branch) or to the Treasury’s Bureau of the Public Debt. Competitive bids must be made in terms of yield and must typically be submitted by 1:00 p.m. eastern time on auction day. Noncompetitive bids must typically be submitted by noon on auction day. While most tenders (or formal offers to buy) are submitted electronically, both competitive and noncompetitive tenders can be made on paper.2

All noncompetitive bids from the public up to $1 million for bills and $5 million for coupon securities are accepted. The lowest yield (i.e., highest price) competitive bids are then accepted up to the yield required to cover the amount offered (less the amount of noncompetitive bids). The highest yield accepted is called the stop-out yield. All accepted tenders (competitive and noncompetitive) are awarded at the stop-out yield. There is no maximum acceptable yield, and the Treasury does not add to or reduce the size of the offering according to the strength of the bids.

EXHIBIT 7.1 Treasury Announcement of an Auction

Historically, the Treasury auctioned securities through multiple-price (or discriminatory) auctions. With multiple-price auctions, the Treasury still accepted the lowest-yielding bids up to the yield required to sell the amount offered (less the amount of noncompetitive bids). However, accepted bids were awarded at the particular yields bid, rather than at the stop-out yield. Noncompetitive bids were awarded at the weighted-average yield of the accepted competitive bids rather than at the stop-out yield.3

Within an hour following the 1:00 p.m. auction deadline, the Treasury announces the auction results. Announced results include the stop-out yield, the associated price, and the proportion of securities awarded to those investors who bid exactly the stop-out yield. Also announced is the quantity of noncompetitive tenders, the median-yield bid, and the bid-to-cover ratio. The bid-to-cover ratio is the ratio of the total amount bid for by the public to the amount awarded to the public. For notes and bonds, the announcement includes the coupon rate of the new security. The coupon rate is set to be that rate (in increments of ? of 1%) that produces the price closest to, but not above, par when evaluated at the yield awarded to successful bidders.

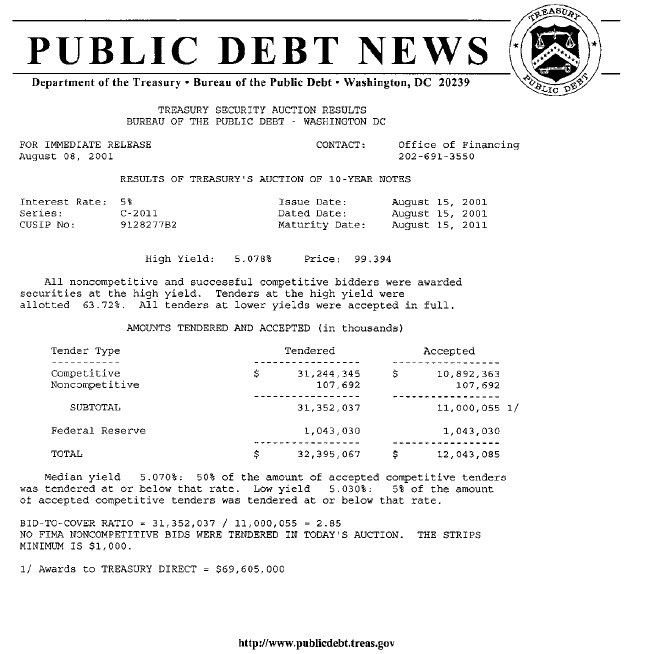

Exhibit 7.2 shows the results of the 10-year note auction. Note the following:

- The high yield or stop yield was 5.078% and this was the yield at which all winning bidders were awarded.

- The coupon rate on the issue was set at 5%.

- Given the yield of 5.078%, the coupon rate of 5%, and the maturity of 10 years, the price that all winning bidders paid was $99.394 (per $100 par value).

- Those bidders who bid the high yield of 5.078 were allocated 63.7% of the amount that they bid.

- Since the total amount of bids by both competitive and noncompetitive bidders was $31,352,037,000 and the total amount awarded was $11,000,055,000, the bid-to-cover ratio was 2.85 (= $31,352,037,000/ $11,000,055,000).

Accepted bidders make payment on issue date through a Federal Reserve account or account at their financial institution, or they provide payment in full with their tender. Marketable Treasury securities are issued in book-entry form and held in the commercial book-entry system operated by the Federal Reserve Banks or in the Bureau of the Public Debt’s Treasury Direct book-entry system.

EXHIBIT 7.2 Results of a 10-Year Note Auction

Primary Dealers

While the primary market is open to all investors, the primary government securities dealers play a special role. Primary dealers are firms with which the Federal Reserve Bank of New York interacts directly in the course of its open market operations. They include large diversified securities firms, money center banks, and specialized securities firms, and are foreign- as well as U.S.-owned. Among their responsibilities, primary dealers are expected to participate meaningfully in Treasury auctions, make reasonably good markets to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s trading desk, and supply market information and commentary to the Fed. The dealers must also maintain certain designated capital standards. The 25 primary dealers as of July 2, 2001 are listed in Exhibit 7.3.

EXHIBIT 7.3 Primary Government Securities Dealers as of July 2, 2001

| ABN AMRO Incorporated | Fuji Securities Inc. |

| BMO Nesbitt Burns Corp. | Goldman, Sachs & Co. |

| BNP Paribas Securities Corp. | Greenwich Capital Markets, Inc. |

| Banc of America Securities LLC | HSBC Securities (USA) Inc. |

| Banc One Capital Markets, Inc. | J. P. Morgan Securities, Inc. |

| Barclays Capital Inc. | Lehman Brothers Inc. |

| Bear, Stearns & Co., Inc. | Merrill Lynch Government |

| CIBC World Markets Corp. | Securities Inc. |

| Credit Suisse First Boston | Morgan Stanley & Co. Inc. |

| Corporation | Nomura Securities International, Inc. |

| Daiwa Securities America Inc. | SG Cowen Securities Corporation |

| Deutsche Banc Alex. Brown Inc. | Salomon Smith Barney Inc. |

| Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein | UBS Warburg LLC. |

| Securities LLC | Zions First National Bank |

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (www.newyorkfed.org/pihome/news/opnmktops/).

Historically, Treasury auction rules tended to facilitate bidding by the primary dealers. Rule changes enacted in 1991, however, allowed any government securities broker or dealer to submit bids on behalf of customers and facilitated competitive bidding by non-primary dealers.4

Auction Schedule

To minimize uncertainty surrounding auctions, and thereby reduce borrowing costs, the Treasury offers securities on a regular, predictable schedule as shown in Exhibit 7.4. Two-year notes are offered every month. They are announced for auction on a Wednesday, auctioned on the following Wednesday, and issued on the last day of the month (or the first day of the following month).

The remaining coupon securities are issued as a part of the Treasury’s Quarterly Refunding in February, May, August, and November. The Treasury holds a press conference on the first Wednesday of the refunding months (or on the last Wednesday of the preceding months) at which it announces details of the upcoming auctions. The auctions then take place on the following Tuesday (5-year) and Wednesday (10-year), with issuance on the 15th of the refunding month.

While the Treasury seeks to maintain a regular issuance cycle, its borrowing needs change over time. Most recently, the improved fiscal situation has reduced the Treasury’s borrowing needs resulting in decreased issuance and a declining stock of outstanding Treasury securities.5 To maintain large, liquid issues, the Treasury eliminated regular issuance of the 3-year note in 1998 and the 52-week bill in 2001. It also reduced issuance of the 5-year note from monthly to quarterly in 1998.

In addition to maintaining a regular issuance cycle, the Treasury tries to maintain a constant issue size for securities of a given maturity. As shown in Exhibit 7.4, typical public issue sizes as of June 2001 were $10–11 billion for the 2-year note, $11–13 billion for the 5-year note, and $9–11 billion for the 10-year note.6 Issue sizes have also changed in recent years in response to the government’s decreased funding needs. Issue sizes for 2-year notes, for example, were $15 billion as recently as 1999, $4–5 billion larger than issue sizes in the first half of 2001.

EXHIBIT 7.4 Auction Schedule for U.S. Treasury Securities

Issue frequency and typical issue sizes as of June 2001 are reported for the six regularly issued Treasury securities. Public issue sizes exclude amounts issued to refund maturing securities of Federal Reserve Banks.

| Issue | Issue Frequency | Public Issue Size |

| 13-week bill | weekly | $12.5-15.0 billion |

| 26-week bill | weekly | $10.5-12.0 billion |

| 2-year note | monthly | $10.0-11.0 billion |

| 5-year note | quarterly | $11.0-13.0 billion |

| 10-year note | quarterly | $9.0-11.0 billion |

| 30-year bond | semiannually | $10.0 billion |

Source: Bloomberg for issue sizes.

Reopenings

While the Treasury regularly offers new securities at auction, it often offers additional amounts of outstanding securities. In February 2000, the Treasury instituted a regular schedule of reopenings for its longer-term debt, whereby it offers additional amounts of outstanding securities at every other auction of its 5-, 10-, and, prior to October 2001, 30-year securities. New 10-year notes, for example, are offered in February and August, with smaller reopenings in May and November.

Exhibit 7.1 shows the August 1, 2001 announcement of two reopenings: a 4¾-year note and a 29½-year bond. The 4¾-year note was originally a 5-year note (issued in May 2001) and the 29½-year bond was originally a 30-year bond (issued in February 2001). For this reason, the coupon rate was provided for each issue. Exhibit 7.5 shows the auction results for the 29½-year Treasury bond. Recall that this was a reopened issue. The coupon rate was already set at 5⅜%. The high yield or stop yield was 5.520%. Given the coupon rate of 5⅜%, the yield of 5.520%, and the maturity of 29½ years, the price that winning bidders paid was $97.900 (per $100 of par value).

Buybacks

To maintain the sizes of its new issues and help manage the maturity of its debt, the Treasury launched a debt buyback program in January 2000. Under the program, the Treasury redeems outstanding unmatured Treasury securities by purchasing them in the secondary market through reverse auctions. The redemption operations are typically announced on the third and fourth Wednesdays of each month and conducted the next day. Each announcement contains details of the operation, including the operation size, the eligible securities, and some of the operation rules and procedures.

The Treasury conducted 20 buyback operations in 2000 (the first in March), and 12 in the first half of 2001. Operations sizes ranged from $750 million par to $3 billion par over this period, with all but two between $1 and $2 billion. The number of eligible securities in the operations ranged from 6 to 26, but was more typically in the 10 to 12 range. Eligible securities were limited to those with original maturities of 30 years, consistent with the Treasury’s goal of using buybacks to prevent an increase in the average maturity of the public debt.

THE SECONDARY MARKET

Secondary trading in Treasury securities occurs in a multiple-dealer over-the-counter market rather than through an organized exchange. Trading takes place around the clock during the week, from the three main trading centers of Tokyo, London, and New York. The vast majority of trading takes place during New York trading hours, roughly 7:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. eastern time. The primary dealers are the principal market makers, buying and selling securities from customers for their own accounts at their quoted bid and ask prices. For the first half of 2001, primary dealers reported daily trading activity in the secondary market that averaged $296 billion per day.7

EXHIBIT 7.5 Results of a 29½-Year Auction

Interdealer Brokers

In addition to trading with their customers, the dealers trade among themselves through interdealer brokers. The brokers provide the dealers with proprietary electronic screens that post the best bid and offer prices called in by the dealers, along with the associated quantities bid or offered (minimums are $5 million for bills and $1 million for notes and bonds). The dealers execute trades by calling the brokers, who post the resulting trade price and size on their screens. The dealer who initiates a trade by “hitting” a bid or “taking” an offer pays the broker a small fee.

Interdealer brokers thus facilitate information flows in the market while providing anonymity to the trading dealers. For the most part, the brokers act only as agents and serve only the primary dealers and a number of non-primary dealers. The brokers include BrokerTec, Cantor Fitzgerald/ eSpeed, Garban-Intercapital, Hilliard Farber, and Tullett & Tokyo Liberty.

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve is another important participant in the secondary market for Treasury securities by virtue of its Treasury holdings, open market operations, and surveillance activities. The Federal Reserve Banks held $535 billion in Treasuries as of June 30, 2001, or 16% of the publicly held stock. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York buys and sells Treasuries through open market operations as one of the tools used to implement the monetary policy directives of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Finally, the New York Fed follows and analyzes the Treasury market and communicates market developments to other government agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board and the U.S. Treasury.

Market Transparency

Despite the huge volume of trading in the secondary market for government securities, the transparency of the market is nowhere near the level of that for common stocks. However, there have been some major strides in the reporting of government securities transactions since 1990. The most prominent example is GovPX, Inc., a private firm created in 1990 by the primary dealers and the interdealer brokers. GovPX provides 24-hour, worldwide distribution of government securities information as transacted by market participants through interdealer brokers. The information reported by GovPX includes the price and size of the best bid and best offer, trade prices and sizes, total volume (aggregate daily volume per issue and aggregate volume across all issues), and current rates and volume (intra-day updates) for repo transactions. The information reported by GovPX is distributed through Bloomberg Financial Markets, Reuters, and Bridge to 50,000 global users.

Trading Activity

While the Treasury market is extremely active and liquid, much of the activity is concentrated in a small number of the roughly 200 issues outstanding. The most recently auctioned securities of a given maturity, called on-the-run or current securities, are particularly active. Analysis of data from GovPX shows that on-the-run issues accounted for 64% of trading activity in 1999. Older issues of a given maturity are called off-the-run securities. While nearly all Treasury securities are off-the-run, they accounted for only 29% of interdealer trading in 1999.

The remaining 7% of interdealer trading in 1999 occurred in when-issued securities. When-issued securities are securities that have been announced for auction but not yet issued. When-issued trading facilitates price discovery for new issues and can serve to reduce uncertainty about bidding levels surrounding auctions. The when-issued market also enables dealers to sell securities to their customers in advance of the auctions, and thereby bid competitively with relatively little risk. While most Treasury market trades settle the following day, trades in the when-issued market settle on the issue date of the new security.

There are also notable differences in trading activity by issue type. According to 1999 data from GovPX, the on-the-run Treasury notes are the most actively traded securities, with average daily trading of $6.4 billion for the 2-year, $4.0 billion for the 5-year, and $2.7 billion for the 10-year.8 Trading activity in when-issued securities is concentrated in the shorter-term issues, with the most active securities being the 2-year note ($1.5 billion), the 13-week bill ($883 million), and the 26-week bill ($651 million). Off-the-run trading is similarly concentrated, with the most active being the 3-month bill ($157 million per issue), the 2-year note ($86 million per issue), and the 26-week bill ($63 million per issue). Trading in longer-term off-the-run securities is extremely thin, with mean daily per-issue trading of just $20 million for the 5-year note and $10 million for the 10-year note.

Quoting Conventions for Treasury Coupon Securities

In contrast to quoting conventions for Treasury bills, discussed in Chapter 6, Treasury notes and bonds are quoted in the secondary market on a price basis in points where one point equals 1% of par.9 The points are split into units of 32nds, so that a price of 96-14, for example, refers to a price of 96 and 14 32nds or 96.4375 per 100 of par value. Following are other examples of converting a quote to a price per $100 of par value:

| Quote | No. of 32nd | Price per $100 par |

91-19 |

19 | 91.59375 |

| 107-22 | 22 | 107.6875 |

| 109-06 | 6 | 109.1875 |

The 32nds are themselves often split by the addition of a plus sign or a number. A plus sign indicates that half a 32nd (or a 64th) is added to the price, and a number indicates how many eighths of 32nds (or 256ths) are added to the price. A price of 96-14+ therefore refers to a price of 96 plus 14 32nds plus 1 64th or 96.453125, and a price of 96-142 refers to a price of 96 plus 14 32nds plus 2 256ths or 96.4453125. Following are other examples of converting a quote to a price per $100 of par value:

| Quote | No. of 32nds | No. of 64ths | No. of 256ths | Price per $100 par |

91-19+ |

19 | 1 | 91.609375 | |

| 107-222 | 22 | 2 | 107.6953125 | |

| 109-066 | 6 | 6 | 109.2109375 |

In addition to price, the yield to maturity is typically reported alongside the price.

Typical bid-ask spreads in the interdealer market for the on-the-run coupon issues range from 1/128 point for the 2-year note to 3/64 point for the 30-year bond, as shown in Exhibit 7.6. A 2-year note might therefore be quoted as 99-082/99-08+ whereas a 30-year bond might be quoted as 95-23/95-24+. Bid-ask spreads vary with market conditions, and are usually wider outside of the interdealer market and for less active issues.

ZERO-COUPON TREASURY SECURITIES

The Treasury does not issue zero-coupon notes or bonds. These securities are created from existing Treasury notes and bonds through coupon stripping. Coupon stripping is the process of separating the coupon payments of a security from the principal and from one another. After stripping, each piece of the original security can trade by itself, entitling its holder to a particular payment on a particular date. A newly issued 10-year Treasury note, for example, can be split into its 20 semi-annual coupon payments and its principal payment, resulting in 21 individual securities. As the components of stripped Treasuries consist of single payments (with no intermediate coupon payments), they are referred to as Treasury zero coupons or Treasury zeros or Treasury strips.

On quote sheets and vendor screens Treasury strips are identified by whether the cash flow is created from the coupon (denoted “ci”), principal from a Treasury bond (denoted “bp”), or principal from a Treasury note (denoted “np”). Strips created from coupon payments are called coupon strips and those created from the principal are called principal strips. The reason why a distinction is made between coupon strips and principal strips has to do with the tax treatment by non-U.S. entities as discussed below.

As they make no intermediate payments, strips sell at discounts to their face value, and frequently at deep discounts due to their oftentimes long maturities. On June 29, 2001, for example, the closing bid price for the February 2031 principal strip was just $19.41 (per $100 face value).

Zero-coupon instruments such as Treasury strips eliminate reinvestment risk. Consequently, the yield at the time of purchase on strips is the pre-tax return that will be realized if an issue is held to maturity. Strips enable investors to closely match their liabilities with Treasury cash flows, and are thus popular with pension funds and insurance companies. Strips also appeal to speculators as their prices are more sensitive to changes in interest rates than coupon securities with the same maturity date.

EXHIBIT 7.6 Bid-Ask Spreads for U.S. Treasury Securities

Statistics for the spread between the best bid and the best offer in the interdealer market are reported for the on-the-run securities of each issue. Bill spreads are reported in yield terms in basis points and coupon spreads are reported in price terms in points.

| Issue | Median Spread | 95% Range |

| 13-week bill | 0.5 basis points | 0-2.5 basis points |

| 26-week bill | 0.5 basis points | 0-2.5 basis points |

| 2-year note | 1/128 point | 0-1/64 point |

| 5-year note | 1/64 point | 0-2/32 point |

| 10-year note | 1/32 point | 0-2/32 point |

| 30-year bond | 3/64 point | 0-6/32 point |

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on 1999 data from GovPX, Inc.

The Treasury introduced its Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities (STRIPS) program in February 1985 to improve the liquidity of the zero-coupon market. The program allows the individual components of eligible Treasury securities to be held separately in the Federal Reserve’s book entry system. Institutions with book-entry accounts can request that a security be stripped into its separate components by sending instructions to a Federal Reserve Bank. Each stripped component receives its own CUSIP (or identification) number and can then be traded and registered separately. The components of stripped Treasuries remain direct obligations of the U.S. government. The STRIPS program was originally limited to new coupon security issues with maturities of 10 years or longer, but was expanded to include all new coupon issues in September 1997.10

Reconstitution

Since May 1987, the Treasury has also allowed the components of a stripped Treasury security to be reassembled into their fully constituted form. An institution with a book-entry account assembles the principal component and all remaining interest components of a given security and then sends instructions to a Federal Reserve Bank requesting the reconstitution.

Tax Treatment

A disadvantage of a taxable entity investing in stripped Treasury securities is that accrued interest is taxed each year even though interest is not paid. Since tax payments must be made on interest earned but not received, these instruments are negative cash flow instruments until the maturity date.

One reason strips are identified on quote sheets and vendor screens by whether the cash flow is created from the coupon or the principal is that some foreign buyers have a preference for the strips created from the principal. This preference is due to the tax treatment of interest in their home country. Some countries’ tax laws treat the interest as a capital gain—which receives a preferential tax treatment (i.e., lower tax rate) compared to ordinary interest income-if the stripped security was created from the principal.

SUMMARY

U.S. Treasury securities are obligations of the U.S. government issued by the Department of the Treasury. They play several important roles in financial markets, serving as a pricing benchmark, hedging instrument, reserve asset, and investment asset.

Investors in Treasury securities are perceived not to be exposed to credit risk. However, investors in Treasuries are exposed to interest rate risk and reinvestment risk, and investors in fixed-rate Treasuries are exposed to inflation risk. By investing in Treasury strips (i.e., Treasury zero-coupon securities), an investor eliminates reinvestment risk.

The regular and predictable issuance of Treasuries has been disrupted in recent years by the government’s decreased funding needs. Recent debt-management changes include the suspension of issuance of the 52-week bill and the 30-year bond and the introduction of a debt buyback program.