28

Power Policy and Power Development in India During the Post-Liberalization Period

Vijayamohanan Pillai N.

28.1 Power Sector in India: Organization and Regulation

By the time of Independence, power supply in India had been largely in the hands of small private companies, besides some municipalities and government electricity departments, all confined to some urban centres. The sector was governed by the Indian Electricity Act (IEA), 1910, which was regulatory in character. Soon after Independence, Electricity (Supply) Act (E(S) Act), 1948 was enacted and under the Act, the State Electricity Boards (SEBs) and the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) were created: the SEBs, originally proposed to be autonomous corporate bodies in the public sector, were entrusted with monopoly rights for power development in the states, and the CEA, with the responsibility for the overall policy and coordination at the national level for power development. The Authority, inter alia, conducts the techno-economic appraisal of the project reports in respect of setting-up of generating stations in the country and issues techno-economic clearance (TEC) for projects. The West Bengal Electricity Board was the first (on 1 May 1956) and the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) was the second (on 31 March 1957) SEB to be established. The E(S) Act in fact led to the ‘public sectorization’ of the Indian Electricity Supply Industry (ESI) which policy was later formalized by the Industrial Policy Resolution, 1956 that reserved the production of power for the public sector. Thus, as a matter of the policy, the licences of five private companies, two in Bombay and one each in Calcutta, Ahmedabad and Surat, licensed under the IEA, 1910, which expired were not renewed and their businesses were taken over by the SEBs. Power is placed in the concurrent list of the Indian Constitution, with the states having the primary responsibility for power development in their respective areas of jurisdiction.

Till the turn of the 1990s that ushered in an era of reforms in the power sector, the governance structure of the Indian ESI had been one of the public sector regulations, with the vertically integrated functions of electricity generation, transmission and distribution (including supply) being regulated by the two acts—the IEA, 1910 and E(S) Act, 1948, together with the amendments, and supported by the Indian Electricity Rules (IER), 1956. The IEA, 1910 provided for the issue of licences to supply electricity and outlined procedures to regulate the licences, while the E(S) Act, 1948 had as its objective rationalization of the power development at the state level through the SEBs and at the national level through the CEA. The IER, 1956 laid down technical standards for power supply, construction of T&D lines and safety standards for electrical installations. The principles of the financial performance of SEBs contained in Section 59 of the E(S) Act, 1948 were amended with effect from 3 June 1978 such that the SEBs were to adjust their tariff from time to time, after taking credit for any subvention from the state government, in order to ensure that the total revenue shall, after meeting all expenses properly chargeable to revenues, leave such surplus as the state government may specify. The amendment enabled state governments, if it deemed expedient to do so, to notify the SEB as a body corporate and the desirability of SEBs converting a part of the outstanding loans into equity was also recognized.

In the early 1960s, taking into account the uneven distribution of resources in different states for power development, it was felt imperative to reap the advantages of the integrated operation of power systems at the regional level. Thus, the country was divided into five regions and Regional Electricity Boards (REBs) were established in 1964 to coordinate the integrated operation of the power system in these regions and the Regional Load Dispatch Centres (RLDCs) to monitor that of the regional grids. The REBs were given statutory status in 1991 through amendment in the E(S) Act, 1948 to strengthen grid management and enforce grid discipline. In November 1996, REBs were given the authority to decide on plant dispatch, that is, to decide which plants should be on line to meet demand and which should be backed down in case of a fall in demand, on the basis of the merit-order-operation clause.

The recognition of the inadequate resource availability in the states led to the setting up in the central power sector of the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC, 1975), National Hydro Electric Power Corporation (NHPC, 1975) and North Eastern Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO, 1976). In addition to these, nuclear power plants are also in the central sector, under the charge of the Atomic Energy Commission, and the Nuclear Power Corporations under the Department of Atomic Energy.

A national grid that facilitates inter-regional transmission of power was the next step towards a logical conclusion. Section 27A of the IEA, 1910 provides for a Central Transmission Utility (CTU) to undertake transmission of energy through an interstate transmission system and to discharge all functions of planning and coordination relating to interstate transmission system with state transmission utilities, central government, state governments, generating companies, etc. Thus, in 1989, the Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd. (PGCIL) came into operation with the central sector transmission lines as the CTU. The transmission assets of the NTPC, NHPC and Neyveli Lignite Corporation (NLC) were transferred to this new entity; in 1994, the PGCIL took over the charge of the RLDCs also.

28.2 Performance and the Background for Reforms

The installed capacity in the Indian ESI, which was only 1,564 MW in 1950–51, increased to 112,058 MW in 2003–04, marking an annual compound growth rate of about 8.4 per cent, and electricity generation increased from 5,100 million units (MU) in 1950–51 to 558.1 billion units (BU) in 2003–04, at the 9.3 per cent per year growth rate. The per capita consumption of electricity, which was less than 15 units at Independence, rose to 408 kWh in 2001 at the 6.4 per cent growth rate. Among other growth indicators, the percentage of villages electrified increased from 0.54 in 1950–51 to 86.5 (of the total 587,258 inhabited villages) in 2002–03 and irrigation pump-sets energized numbered 13.4 million out of a possible 19.6 million by 2001–02 (Government of India, 2002).

However, these apparent achievements appear trifle in relation to real requirements. Serious power shortages have been plaguing the country for a long time; at the commencement of the Eighth Plan (1991–92), India faced a peaking shortage of about 19 per cent and energy shortage of about 8 per cent, and the situation remained almost so by the end of the Plan period. The total energy shortage, during 2000–01, was 39,816 MU, amounting to 7.8 per cent and the peak shortage was 10,157 MW translating to 13 per cent of the peak demand. It has been found, based on the demand projections made in the 16th Electric Power Survey that over 100,000 MW additional generation capacity needs to be added to meet the national objective of ‘power for all by 2012’. It has been estimated that this would involve investments to the extent of Rs 900,000 crores in the sector (Government of India, 2004).

In the face of such shortages, it is no wonder that the annual per capita power consumption of India, at about 408 kWh in 2001, was among the lowest in the world.1 Moreover, nearly 80,000 villages are yet to be electrified. According to the 2001 Census, of the rural population, which constitutes about 72 per cent of the total population of the country, about 57 per cent of the rural households have no access to electricity. Still worse, the end-users of electricity (i.e. households, farmers, commercial establishments, industries) are confronted with frequent power cuts, both scheduled and unscheduled.

This chronic shortage situation has been the inevitable outcome of a cumulative decline in capacity addition in the power sector, explained by the compounded effects of an increasingly inadequate investment tempo2 and the inordinate, but avoidable, delays in project completion. Investment deficiency and inefficiency have thrived in both the segments of the sector—central and state (as also private). Coupled with this have been the following:

- Lack of optimum utilization of the existing generation capacity

- Inadequate inter-regional transmission links

- Inadequate investments in the transmission and distribution infrastructure resulting in power evacuation constraints from the generating stations

- Huge transmission and distribution losses, largely due to outright theft3 and unmetered supply and inefficient/defective metering

- Lack of grid discipline4

- Inefficient use of electricity by the end-consumer.

In addition to such dismal performance has been the poor financial health of the SEBs, which, in turn, has mainly been due to the poor performance on the distribution front. Out of the total energy generated, only 55 per cent is billed and only 41 per cent is realized. The gap between average revenue realization and average cost of supply has been constantly increasing. For instance, during the year 2000–01, the average cost of supply was Rs 3.04 per unit and the average revenue was Rs 2.12 per unit; that is, there was a gap of 92 paise for every unit of power supplied. All this has caused substantial erosion in the volume of internal resource generation by the SEBs. The annual losses of SEBs have now reached a level of about Rs 26,000 crores, rendering them unable to make full payments to the Central Power Sector Utilities (CPSUs) for purchases of power and coal. This has now resulted in an accumulation of outstandings of more than Rs 40,000 crores by the SEBs.

The problems of inefficiency and deficiency have had behind it a long history of abuses and aberrations of public sector management. The Rajadhyaksha Committee on Power thus commented on the plight as far back as in 1980:

‘Under the Electricity Supply Act, which regulates the operation of the SEBs, the Boards were not till recently specifically required to earn a return on the capital they use. A number of committees, of which particular mention should be made of the Venkataraman Committee, 1964, examined the working of the SEBs and recommended a gross return of 9.5 per cent (excluding electricity duty) on capital employed after providing for operating expenses and depreciation. However, when the statute was amended in 1978, although it was provided that Boards should earn a positive return, no specific figure was mentioned.

‘In actual practice, however, the Boards are often regarded as promotional agencies to be used to subsidize different classes of consumers and with little or no control over their tariff policy. As a result, on the whole, the returns specified by the Venkataraman Committee have not been realized and on the contrary, large arrears of interest are due to the state governments on the loans given by them to the SEBs.’

‘Besides low tariffs, the causes of the poor financial performance are the low operating efficiencies, high capital cost of projects due to long delays in construction and high overheads—mainly the result of heavy overstaffing. Although precise comparisons are not possible, the average employees per MW of installed capacity in India is 7, compared to 1.2 in the USA, 1.5 in Japan, and 1.7 in the UK. Within the country, the expenditure on salaries varies from 12 per cent to 40 per cent of the total income of the SEBs. Much of this overstaffing is due to SEBs being compelled under political pressures to take on people they do not need.

‘The result of all this is that many of the Boards are wholly dependent upon the state government even for meeting their normal operating expenses making it even more difficult for them to function as the autonomous bodies which they were set up to be.

‘The weaknesses in the management of the utilities, in particular the SEBs, . . . arise partly out of the desire of some state governments to exert a high degree of day to day control on the operations of the Boards, and partly due to management culture, inherited from the bureaucratic style of functioning, that most SEBs had when they were government departments’. (Report of the (Rajadhyaksha) Committee on Power 1980: 4).

28.2.1 Indian Power Sector on the Reform Path

Thus, the ill-ridden performance of the ESI had already left it cash-strapped. And to crown the worst, there descended before the sector an impasse out of the infamous fiscal crisis at the dawn of the 1990s. In fact, the capacity-deficient Indian ESI had the rude shock when confronted with the fiscal crisis begotten revelation that the conventional budgetary funds support for capital augmentation programmes had dried up. It should, however, be pointed out that there had been a steady deceleration over time in the plan provisions to the power sector, leading to cumulative investment deficiency. The predicament thus posed had also its readymade solution—the private sector. But the Indian capital market was found too feeble to support the sector and hence the significance of the foreign sector. It was also hoped that there would be a side benefit in respect of efficiency, which remained at an unacceptably low level. This efficiency was thought to be improved through the often-claimed better management and higher technical performance of the private sector.

28.2.2 Private Sector Participation in Generation

The reform process in the Indian power sector was initiated in 1991. The generation sector of the vertically integrated natural monopoly of the ESI had become increasingly recognized as having the potential to accommodate competition and thus it was the natural starting point for introducing private participation, both domestic and foreign.5 This was accomplished through the October 1991 amendment to 1910 and 1948 Acts that for the first time introduced the concept of a generating company as a distinct entity (The Electricity Law (Amendment) Act, 1991)—the first amendment with structural implications for the ESI in India. Under this amendment act, private companies can now build, own and operate power stations, subject to certain terms and conditions detailed subsequently in the Notification of 13 March 1992, from the Ministry of Power and Non-Conventional Energy Sources, Department of Power (see Box 28.1). The independent power producers (IPPs) were expected to negotiate power purchase agreements, with the concerned SEBs, that would reflect those terms and conditions. In addition to an Investment Promotion Cell (IPC), a high powered board (under the Chairmanship of the Minister of Power) was also set up to facilitate project implementation by serving as ‘a single-point forum for faster clearance of the proposals received within a definite time frame’ (quoted in World Bank 1995: 84)

The IPP entry on the basis of negotiation (memorandum of understandings, MoU) with the tariff determined on cost-plus formula had the inherently inevitable rate padding tendency that led to higher tariffs. This belated (and hence costly) realization resulted in the January 1995 policy that provided for entry of IPPs on the basis of competitive bids only, administered by the states (for their purchases) and by the centre (for megaprojects, for example). Guidelines were issued by the Ministry of Power for such competitive bidding processes. In October 1995, the scope for private investment was further enlarged, inviting private sector participation in the renovation and modernization (R&M) and life extension (LE) of existing power plants,6 which are cost-effective, environmental-friendly and require shorter lead time. R&M and LE yield an additional capacity at a cost of only 15–25 per cent of the cost of equivalent new capacity (Government of India, 2000: 19).

Box 28.1: Key Features of the Power Sector Reform Policy Introduced, Starting 1991

- Private sector companies may build, own and operate generating stations of any size and type (except nuclear).

- Foreign equity is permitted in generation companies.

- A post-tax return on equity of 16 per cent at a plant load factor (PLF) of 68.5 per cent is guaranteed, based on a two-part tariff formula, which covers both fixed and variable costs.

- Additional returns (of 10–12 percentage points) on equity allowed where the PLF exceeds 68.5 per cent.

- Free repatriation of dividends and of interest on foreign equity and loans.

- A five-year tax holiday for new generation and distribution companies.

- Protection from exchange rate fluctuations.

- Depreciation rates on plant and machinery have been increased.

- Custom duty on imports of equipment has been reduced by 20 per cent.

- A private power generator can sell power to anyone with the permission of the concerned State Government.

—World Bank 1995: 83; Box 3.2.

The government has recently reviewed the policy on automatic approval of foreign equity participation in the power sector (both in generation and in T&D) and revised the limit from 74 per cent to 100 per cent of equity participation in cases where project cost does not exceed Rs 15,000 million. Again, for speedy environmental clearance, the Ministry of Environment and Forests has agreed to delegate powers to the states regarding environmental clearances for cogeneration projects and captive plants up to 250 MW, coal-based plants using fluidized technology up to 500 MW, power plants on conventional technology up to 250 MW and gas/naphtha-based plants up to 500 MW. In November 1998, the limit in respect of various categories of power projects beyond which the concurrence of the CEA would be required was enhanced. The 1991 policy had envisaged that not more than 40 per cent of the total outlay for the private sector units might be raised from Indian public financial institutions. The government has recently removed the ceiling for the extent of domestic debt, subject to the adoption of a norm by Indian public financial institutions, whereby a higher domestic debt component would be allowed for projects based on indigenous equipment.

During 1998–99, the central government announced a policy on hydro-power development with a view to exploiting at a faster rate the vast hydropower potential available in the country. Subsequently, guidelines were issued that simplify the procedure for the TEC by the CEA, reducing the normative availability factor for hydropower stations from 90 per cent to 85 per cent and allowing the sale rate of secondary energy at the same rate as applicable for primary energy in order to provide an additional incentive for attracting investment in hydro projects.

For the purpose of financing the power sector, new arrangements have also been made. These include setting up of the infrastructure development finance company, broadening the scope of the public sector Power Finance Corporation (PFC), allowing an active role for the PFC in negotiating loans from international banks and foreign capital markets, constituting a power development fund by the power ministry for speedy implementation and execution of power projects as also to finance feasibility studies for setting up power plants, mooting a Power Trading Company (PTC) to purchase power from power-surplus regions and sell it to power-deficient regions, launching of ‘infrastructure bonds’ to channel household savings into the power sector and involving provident funds as a potentially important source of funding.

28.2.3 Transmission Sector

Though a number of amendments were added to the 1910 and 1948 acts, they were of only clarificatory nature. In contrast, the first amendment act (The Electricity Law (Amendment) Act, 1991) with structural implications for the ESI in India was designed in 1991 to introduce the concept of a generating company as a distinct entity. In 1998, similarly, the Electricity (Amendment) Act, 1998 treated transmission as a separate entity of business which could be licensed and which could thus facilitate private participation. In this new light, the Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd. (PGCIL) that owns and operates the central sector transmission assets was notified as the Central Transmission Undertaking (CTU). This enabled it to gain explicit legal control of the grid management system in the country. Similar entities at the state level were notified as State Transmission Undertakings (STUs). Among the main functions of these undertakings are identification of transmission lines, issue of specifications and selection of private party ready to participate in the sector. Private sector participation in transmission sector investment is proposed to be limited to build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) basis projects under the supervision and control of the PGCIL. Private sector entry is welcomed through two routes: (i) 100 per cent equity; or (ii) joint venture with the PGCIL. In the latter case, 26 per cent stake would be held by the PGCIL and the remaining by the private partner or a consortium. The PGCIL would be the authority to identify such projects at national and regional levels as well as to select private investors and to recommend them to the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) for issuance of licences; at the state level, STUs would be the corresponding authority to recommend to the State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC) (vide infra). The licences thus issued would be for a period of 30 years for the private investor’s BOOT project. The PGCIL, if it is so prepared, can take the line on rental basis; in the case of joint venture, the tariff would be based on cost-plus basis.

28.2.4 Electricity Regulatory Commissions

It was unequivocally emphasized that the future development of the ESI in India depended on two factors: (i) improved operating efficiency of the SEBs; and (ii) their financial viability. To achieve this objective, it was then proposed and decided that the ESI be restructured and unbundled wherever possible for effective private participation, assumed to usher in competition and efficiency. Since the private power sector pre-supposes regulation, it was further acknowledged that unbundling could not effectively take place, unless regulators were appointed first.

Thus, the IEA, 1910 and the E(S) Act, 1948 were amended in 1996 to enable the setting up of State and Central Level Electricity Regulatory Commissions (see Appendix 28.2 for the functions of the CERC and SERCs). Each state and union territory was to set up an independent SERC to deal with tariff fixation, that is, to determine the tariff for wholesale or retail sale of electricity and for the use of transmission facilities. Later on the Government of India (GoI) issued an ordinance which was later converted into an act in 1998 (The Electricity Regulatory Commission (ERC) Act, 1998) to enable the appointment of regulators at the national and state level. At the centre, a CERC was set up (on 24 July 1998) to deal with all state-level appeals and interstate power flows. Such commissions had already been set up in Odisha in 1996 and in Haryana in 1998 under state legislation. With the concurrence of the GoI, Andhra Pradesh passed a separate regulatory and restructuring act in 1999, in line with the Odisha and Haryana acts. Due to the federal nature of our constitution, the central government had decided that though it would pass an Electricity Regulatory Commission Act, it would not impose a restructuring model on any state by central legislation, and that it would only issue guidelines and model acts for the consideration of the states.

Since 1 April 1999, the CEA has entrusted the CERC with the task of regulating power tariffs of central government power utilities, interstate generating companies and interstate transmission tariffs. One of the important objectives of the CERC is to improve operations in the power sector, by means of measures such as increased efficiency, large investments in the transmission and distribution (T&D) systems, time-of-day pricing and power flow from surplus to deficit regions. Further, the central government or the CERC can grant a transmission licence to anyone to construct, maintain and operate any interstate transmission system under the direction, control and supervision of the central transmission utility.

A number of SEBs are on the reform/restructuring path. So far 22 states namely Odisha, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Delhi, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Uttaranchal, Goa, Bihar, Jharkhand, Kerala and Tripura have either constituted or notified the constitution of the SERC. 18 SERCs viz., Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Uttaranchal, Jharkhand and Kerala have issued tariff orders and the SEBs of Odisha, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal Rajasthan, Delhi and Madhya Pradesh have been unbundled/corporatized. 29 states have securitized their dues (either fully or partially) over Rs 28,000 crores to central undertakings. Consequently, cash realizations improved to nearly 100%. Distribution has been privatized in Odisha and Delhi, and the states of Gujarat and Karnataka have started handing over parts of the distribution system on management contract to franchisees. Jharkhand has also invited expression of interest for handing over distribution in Ranchi to franchisees. (See Appendix 28.3 for the details of progress of reform in the Indian power sector).

Most of the states have identified feeder managers to increase accountability. This is helping the utilities in reducing aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses. Computerized billing and consumer complaint centres have been started in selected towns of Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Consumer indexing has been started in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. A high-voltage distribution system has been introduced for reduction in pilferage of electricity in CPDCL (Andhra Pradesh), NDPL (Delhi), West Bengal, Noida (Uttar Pradesh), etc. 39 major towns in the country have introduced monitoring of the reliability index.

The first move towards such reform process was initiated in Odisha, even before the formulation of the CERC at the centre. The Orissa Electricity Regulatory Commission was the first of its kind in the country, designed as an independent regulatory commission to regulate the power sector in the state. The World Bank has sanctioned a loan of 350 million dollars to Odisha for its power sector reforms.

Restructuring of the Odisha power sector started in 1996 with the enactment of the Orissa Reforms Act, 1995. The erstwhile vertically integrated utility of the Odisha SEB was unbundled into separate corporations—Grid Corporation of Orissa (GRIDCO) for transmission and distribution and Orissa Hydro Power Corporation (OHPC) for hydel generation. Subsequently, four wholly owned subsidiary companies of the GRIDCO were carved out for distribution and later these subsidiary companies were privatized by the sale of 51 per cent of the share of GRIDCO’s equity holding. The BSES took over three companies in the north, west and south zones (NESCO, WESCO and SOUTHCO, respectively), and the AES Corporation of the USA, the central zone (CESCO). However, the AES has later backed out from the managerial responsibility of the company and the CESCO is now administered by a government official. The Orissa Power Generation Corporation (OPGC) has been disinvested to the extent of 49 per cent.

The transition process involved valuation, apportioning and adjustments of assets and liabilities. Adjustment of subsidies and electricity charges, totalling Rs 340 crores, payable to the OSEB/GRIDCO against the upvalued amount of Rs 1,194 crores, cast a heavy strain on the finances of the GRIDCO. Moreover, a major proportion of past losses and overdue liabilities were retained by the GRIDCO with a view to successful privatization of the distribution companies. The four distribution companies were assigned only the project-related liabilities totalling Rs 630 crores, while the GRIDCO retained liabilities totalling Rs 1,950 crores. In addition, the GRIDCO issued Rs 253 crores worth of shares and Rs 400 crores worth zero-coupon bonds to the state government. All these left GRIDCO heavily cash-strapped and forced to default to generating companies and other suppliers (Government of India, 2000: 9). Hence, the significance of the financial assistance from the institutional lenders, especially the World Bank through its adaptable program loans. In fact, Odisha has been implementing the model of power sector restructuring as conceived by the World Bank (Dixit, Sant and Weigle, 1998).

The Haryana SEB was unbundled into two separate entities on 14 August 1998—the Haryana Power Generation Corporation for generation and the Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam for transmission. For distribution, the state has been divided into two zones, viz., north (managed by the Uttar Vidyut Vitaran Nigam) and south (managed by the Dakshin Vidyut Vitaran Nigam).

Andhra Pradesh has received presidential assent to its Electricity Reform Bill, 1998, which has led to the formulation of the SERC. Under the provisions of the Andhra Pradesh Electricity Reforms Act, two corporations, viz., the Andhra Pradesh Power Generation Corporation Limited (AP GENCO) and the Transmission Corporation ofAndhra Pradesh Limited (AP TRANCO) have replaced the Andhra Pradesh SEB. It has been decided that the distribution in the state will be divided into five zones and 51 per cent of the stake in distribution will be offered to the private sector. It should be remembered that the AP Electricity Regulatory Commission has recently hiked the tariff to such an extent that the whole state has been paralysed for many days together with public agitation. As per a report, the revised power cost in AP is estimated to be about 16 per cent, compared with a world average power cost of only seven cents (The Hindu Business Line, 29 July 2000).

Karnataka is the first state in India to have separated the generation of power from transmission and distribution by setting up the Karnataka Power Corporation Limited (KPCL) as far back as in 1970. The transmission business of the Karnataka SEB has recently been corporatized (Karnataka Power Transmission Corporation Limited, KPTCL) and Karnataka proposes to incorporate distribution companies by the end of 2000 and to privatize them by December 2001. Under the current proposal, already cleared by the state government, 51 per cent of the equity is to be provided to the private sector promoters/bidders and the remaining 49 per cent to other intending equity holders including financial institutions, with a small stake for the KPTCL. The KPCL has recently decided to insure its assets as a prelude to restructuring and the subsequent disinvestment (either splitting of the KPCL into separate thermal and hydel power generation companies or converting the KPCL into a single state-owned holding company with equity stakes in both these ventures separately). With this move, the KPCL will be the first public sector company in the country to insure its assets.

28.2.5 Accelerated Power Development Programme

A new central assistance scheme, viz., Accelerated Power Development Programme (APDP), has come into force for leveraging reforms in the power sector in the states. The APDP will finance projects relating to: (i) renovation and modernization/life extension/ updating old power plants (thermal and hydel); and (ii) upgradation of subtransmission and distribution network (below 33 kV or 66 kV) including energy accounting and metering. Priority is given to projects from those states that commit themselves to a time-bound programme of reforms in terms of:

- Setting up the SERC and making it operational as envisaged under the law and the state power utilities sending the first proposal for fixation of tariff to the SERC

- Creating separate profit centres/restructuring generation/transmission/distribution to make the system accountable

- Dividing the state into a number of zones for the purpose of distribution and privatization of each zone or alternatively giving responsibility of electricity distribution to panchayats/users’ associations/co-operatives/franchisees, in case it is found that improvement in public sector management is not feasible

- Completing 100 per cent of metering in a planned manner.

It is also stipulated that APDP funds shall also be available to the states which otherwise achieve high level of operational efficiency and financial viability. The fund under the APDP is scheme-specific, provided to the state governments as a special central assistance over and above the normal central plan allocation. The state government should release this fund to the state power utility under the same terms and conditions as they receive from the central government; within a week of the said amount being credited to the state government account, confirmation should be sent to the GoI; otherwise, it will be treated as diversion of fund.

No project will receive assistance both under the APDP and under the Accelerated Generation and Supply Programme (AG&SP) of the Power Finance Corporation (PFC). Energy audit, accounting and system studies, however, can be financed through the AG&SP under the model distribution scheme. Renovation and modernization/life extension projects costing less than Rs 100 crores will be financed under the APDP and those costing more than Rs 100 crores will be financed under the AG&SP of the PFC. It is also provided that cent per cent metering only within the identified distribution circles will be financed under the APDP.

28.2.6 Accelerated Power Development and Reform Programme (APDRP)

The objectives in the distribution reform segment of the APDRP are to achieve 100 per cent metering, energy audit, better high-tension-to-low tension (HT-LT) ratio, replacement of distribution transformers, and information and technology (IT) solutions relating to power flow at critical points to ensure accountability at all levels. These should lead to a qualitative improvement at the consumers’ end so as to raise the level of satisfaction, besides improving revenue realization of the utilities. Under APDRP schemes, projects of Rs 16,610.19 crores have since been sanctioned.

The scheme has two components—an investment component and an incentive one. Under the investment component, additional central assistance of half the project cost is provided for strengthening and upgradation of subtransmission and distribution networks. The rest has to be provided by the SEBs and utilities from the PFC, Rural Electrification Corporation and other financial institutions or from their own resources as counterpart funds. The release of funds, however, is linked to measurable targets. The performance criteria include putting in place a regulatory framework, restructuring of SEBs, reduction in transmission and distribution losses, curtailing revenue arrears, increased plant load factor, manpower reduction and reduction in cash losses. Under the incentive component, on the other hand, an incentive equivalent to 50 per cent of the actual cash-loss reduction by SEBs/utilities is provided as grant. For this, 2000–01 is the base year for the calculation of loss reduction in subsequent years.

Another related programme is the AG&SP with funding from both the REC and PFC. Loan up to about Rs 10,000 crores would be available under this programme mainly for renovation and modernization (R&M) of power plants.

28.2.7 Further Distribution Reform Programmes

Distribution reforms have been identified as the key area for putting the sector on the right track. The strategies adopted by the Ministry of Power (MoP) in this direction include the following:

- Developing district-level distribution improvement plans/projects for all districts. The Ministry/CEA will help the states in capacity-building measures in areas related to technical and commercial activities as well as planning and deployment of personnel. Assistance would also be provided to SEBs to improve their accounting practices.

- Setting up of district level energy committees for monitoring and resource planning.

- Developing 60 distribution circles as centres of excellence for distribution reform. The funds for the project would be provided by the centre under the APDP. These centres would act as models for replication in other districts.

- 100 per cent metering and effective management information system (MIS) for monitoring at feeder level, backed up by detailed energy audit to bring accountability into the system at all levels.

- Taking high-voltage lines up to the load centre to prevent theft of power and reduce technical losses.

- Signing of MoUs with states for undertaking distribution reforms in a time-bound manner and linking the support of GoI to achieve predetermined milestones.

- Privatization/corporatization of distribution.

- Tariff rationalization by SERCs.

28.3 Electricity Act, 2003 (Notified in June 2003)

Recently, the central government has introduced a new act, which stands to replace the existing three Acts that govern the power sector. The three acts are the IEA, 1910, Indian E(S) Act, 1948 and the recently enacted the Electricity Regulatory Commissions Act, 1998 that together constituted the legal foundation for the ESI in India till now. The Electricity Act, 2003 now replaces all these three acts. The objective of the act is supposed to introduce competition, protect consumers’ interests and provide power for all. The act provides for a national electricity policy, rural electrification, open access in transmission, phased open access in distribution, mandatory SERCs, license-free generation and distribution, power trading, mandatory metering and stringent penalties for theft of electricity. The purported aim is to push the sector onto a trajectory of sound commercial growth and to enable the states and the centre to move in harmony and coordination.

A very significant provision in the act is that all the SEBs of present constitution will ‘wither away’ as the new act comes into effect. This has since the introduction of the bill in 2000 led to a very heated controversy. However, it is open to a state government to set up its own SEB if it wants the existing system to continue. In fact, once the E(S) Act, 1948 is done away with, the very existence of SEBs, the establishment of which was the objective of the act, comes to a natural end. Now the state government needs to reconstitute the SEB, if it so desires, through its own legal provision. At the same time, on the other side, appears the fact that once the SEBs cease to exist following restructuring, the very E(S) Act, 1948 becomes redundant. Hence, the significance of the replacement. Part 13 of the act deals with the reorganization of the SEBs in detail.

The act envisages time-bound radical restructuring in terms of unbundling and corporatization. All the states have to establish SRCs, authorized to supervise, direct and control all the activities in the ESI. This implies that the government interference in the day-to-day affairs of the sector is minimized, though the government is still allowed to wield significant powers. The act also seeks to establish a spot market for electricity through pooling arrangements. This necessitates setting up of an independent system operator for transmission such that the ‘wires business’ becomes one of national dimension rather than interstate dimension. There is a threat, however, lurking in such development in that the concurrent, federal nature of authority of the states on the ESI may soon be superseded by a centralized, unitary authority. The act in fact gives an impression that the subject of electricity, instead of being in the concurrent list, is in the central list, with far too many rooms for centralization and standardization. Policies on all matters, namely the national electricity policy and plan, and even the national policy on stand-alone systems for rural areas and non-conventional systems, and the national policy on electrification and local distribution in rural areas are all matters for formulation by the central government (Section 3, The Electricity Act, 2003).

Box 28.2: A Big ‘No’ to Unbundling and Privatization

Restructuring is being considered [now in India] mainly because the SEBs are operating at loss and are not in a position to meet the electricity demand and are also considered inefficient with high T&D losses and the KSEB is no exception. At the same time, the factors that have led the SEBs into this situation, which are quite well known, have not been removed and no attempt has been made in that direction. … The Task Force is of the view that before contemplating any restructuring, which becomes irreversible, it is to be examined whether the present sickness can be remedied without any drastic surgery by removing the problems that cause the sickness. It is to be stressed that the problems that may arise consequent to restructuring could be more severe than the existing ones, particularly when a large and complex organization like the KSEB is unbundled and split into several units.…

Electric utility, unlike other engineering industries, requires perfect and total coordination between generation and T&D. A composite organization is best suited for this purpose. Financial assistance is likely to be extended to the KSEB from banks and financial institutions including international agencies in case its balance sheet is healthy, which is possible only if it is permitted to follow a rational and sound tariff policy.

The Task Force noted that the utilities, by tradition and practice, are a natural monopoly and there can never be a competitive situation vis-a-vis the consumer. This is for the reason that the consumer has no option to choose from more than one source providing the utility service. The Task Force is of the view that if there were to be a monopolistic situation, Government monopoly, which is subject to Government control, keeping in view the social objective, is far more preferable than a private monopoly where commercial or profit making interests prevail over other considerations. The Task Force, accordingly, strongly recommends against privatization of transmission and distribution activities.

(Executive Summary of the Report

of the Task Force on Policy Issues Relating to Power Sector and Power Sector

Reforms; quoted in Government of Kerala 1998: Annexure 2)

TABLE 28.1 Status of Private Power Projects (PPPs) (Since 1991)

Notes: *Also includes those projects which do not require the techno-economic clearance of the CEA.

**Includes licencees also.

Source: http://www.iitpl.com/mop/nrg71.htm.

The act also plans, in a bid to facilitate a level playing field for transmission sector participants (transmitters), to restrict the role of the central transmission utility—PGCIL— to that of power grid management only, divesting it of the other role of being also a player in the transmission business. This is in the wake of a long-standing feud between the PGCIL and the CERC over a directive issued by the CERC to the Power Grid in 1999 to operate its business and perform its role as a grid manager as separate autonomous business units. The earlier version of the Electricity Bill vested the regulatory control in the transmission sector with the PGCIL; however, the recent version (sixth draft) has restored (in line with the Electricity Amendment Act, 1998) the power to the CERC with some minor modifications.

A major criticism levelled against the act has been that there is not enough emphasis on rural electrification and it actually overemphasizes commercialization of power (in Part 7 of the Act) rather than making power available to everybody.

The act as such has caused much flutter and protest; many states (for example, Kerala) and SEB employees suspect the move of Centre as an attempt to usurp the state’s authority on the ESI and impose restructuring where the state is unwilling.

28.4 Responses to the Opening Up Policy

Quite contrary to the confident expectation in 1991–92, however, the private sector has not come forward to contribute sufficiently to bridging the gap between power demand and supply. Although the CEA has provided techno-economic clearance (TEC) to nearly 30,000 MW and in-principle clearance to another 10,421 MW, only 4,760 MW has been commissioned during the past 10 years (as in January 2001, as shown in Table 28.1). It should be stressed that a whole decade has gone waste by waiting for private sector participation in the power capacity addition programme: the installed capacity (IC) during the last decade grew at an annual average rate of 4.5 per cent only, while the growth rate in the 1970s as well as in the 1980s was 7.5 per cent and 8.2 per cent, respectively. As in March 2001, the private sector accounted for only 10.55 per cent (11,066.5 MW) of the total IC in the Indian power sector (101,657 MW), while the state sector accounts for 59.33 per cent (62,246.5 MW).

Before concluding, it should be stated that there definitely has appeared a silver lining: thanks to controversial power projects, there has been wide public debate as well as informed discussion, though greater transparency in decision making, greater public participation (especially from the civil society) and greater information dissemination are still wanting.

References

Dixit, S., Sant, G. and Weigle, S. (1998). ‘WB—Orissa Model of Power Sector Reforms: Cure Worse Than Disease’, Economic and Political Weekly April 25: 944–949.

Government of Kerala (1998). Report of the (K.P. Rao) Expert Commit-tee to Review the Tariff Structure of KSEB, May. Thiruvananthapuram.

Government of India (2000). Conference of Power Ministers: Agenda Notes. 26 February. Ministry of Power, New Delhi.

Government of India (2002). Annual Report (2001–02) on the Working of State Electricity Boards and Electricity Departments, Planning Commission (Power and Energy), New Delhi. May.

Government of India (2004). Report of the Task Force on Power Sector Investments and Reforms. February Volume 1, Ministry of Power, New delhi.

World Bank (1995). Economic Development in India: Achievements and Challenges, World Bank Country Study, Washington DC.

Appendix 28.1

Historical Background of Legislative Initiatives

- The Indian Electricity Act, 1910

- Provided basic framework for electric supply industry in India.

- Growth of the sector through licences (licence issued by state governments)

- Provision for licence for supply of electricity in a specified area.

- Legal framework for laying down of wires and other works.

- Provisions for laying down the relationship between the licence and consumer.

- The Electricity (Supply) Act, 1948

- Mandated creation of SEBs.

- Need for the state to step in (through SEBs) to extend electrification (so far limited to cities) across the country.

- Main Amendments to the Indian Electricity Supply Act

- Amendment in 1975 to enable generation in the central sector.

- Amendment to bring in commercial viability in the functioning of SEBs—Section 59 amended to make the earning of a minimum return of 3 per cent on fixed assets a statutory requirement (w.e.f. 1.4.1985).

- Amendment in 1991 to open generation to the private sector and establishment of RLDCs.

- Amendment in 1998 to provide for private-sector participation in transmission and also provision relating to transmission utilities.

- The Electricity Regulatory Commission Act, 1998

- Provision for setting up of the Central/State Electricity Regulatory Commission with powers to determine tariffs.

- Constitution of the SERC optional for states.

- Distancing of government from tariff determination.

- The Electricity Act, 2003

- The objective is to introduce completion, protect consumer’s interest and provide power for all.

- To promote sound commercial growth, and to enable the states and centre to move in harmony and coordination.

- To achieve time-bound radical restructuring in terms of unbundling and corporatization.

Appendix 28.2

Functions of the CERC

Provision 79 in Part IX of the Act

- The Central Commission shall discharge the following functions, namely:

- To regulate the tariff of generating companies owned or controlled by the central government

- To regulate the tariff of generating companies other than those owned or controlled by the central government specified in Clause (a), if such generating companies enter into or otherwise have a composite scheme for generation and sale of electricity in more than one state

- To regulate the inter-state transmission of electricity

- To determine tariff for inter-state transmission of electricity

- To issue licences to persons to function as a transmission licences and electricity trader with respect to their interstate operations

- To adjudicate upon disputes involving generating companies or transmission licensee in regard to matters connected with clauses (a) to (d) above and to refer any dispute for arbitration

- To levy fees for the purposes of this Act

- To specify grid code

- To specify and enforce the standards with respect to quality, continuity and reliability of service by licensees

- To discharge such other functions as may be assigned under this Act.

- Without prejudice to the provisions of sub-section (1), the Central Commission may:

- Advise the central government on all or any of the following matters, namely:

- Formulation of national electricity policy and tariff policy

- Promotion of competition, efficiency and economy in activities of the electricity industry

- Promotion of investment in electricity industry

- Any other matter referred to the Central Commission by that government (b) Fix the trading margin in inter-state trading of electricity, if considered necessary

- Advise the central government on all or any of the following matters, namely:

- The Central Commission shall ensure transparency while exercising its powers and discharging its functions.

- In discharge of its functions, the Central Commission shall be guided by the national electricity policy publish under sub-section (2) of section of functions of Central Commission.

Functions of the State Electricity Regulatory Commission

Provision 86 in Part IX of the Act

- The State Commission shall discharge the following functions, namely:

- Determine the tariff for generation, supply, transmission and wheeling of electricity, wholesale, bulk or retail, as the case may be, within the state— providing that where open access has been permitted to a category of consumers under Section 42, the State Commission shall determine only the wheeling charges and surcharge thereon, if any, for the said category of consumers

- Regulate electricity purchase and procurement process of distribution licensees including the price at which electricity shall be procured from the generating companies or licensees or from other sources through agreements for purchase of power for distribution and supply within the State

- Facilitate intra-state transmission and wheeling of electricity

- Issue licences to persons seeking to act as transmission licensees, distribution licensees and electricity traders with respect to their operations within the state

- Promote cogeneration and generation of electricity from renewable sources of energy by providing suitable measures for connectivity with the grid and sale of electricity to any person, and also specify, if it considers appropriate, for purchase of electricity from such sources, a percentage of the total consumption of electricity in the area of a distribution licence

- Adjudicate upon the disputes between the licensees, and generating companies and to refer any dispute for arbitration

- levy fee for the purposes of this Act;

- specify state grid code consistent with the grid code specified under clause (h) of sub-Section (1) of Section 79

- specify or enforce standards with respect to quality, continuity and reliability of service by licensees; and

- discharge such other functions as may be assigned to it under this Act.

- Without prejudice to the provisions of sub-section (1), the State Commission may:

- Advise the state government on all or any of the following matters, namely:

- Promotion of competition, efficiency and economy in activities of the electricity industry;

- Promotion of investment in electricity industry;

- Reorganization and restructuring of electricity industry in the state;

- Matters concerning generation, transmission, distribution and trading of electricity or any other matter referred to the state commission by that Government.

- fix the trading margin in intra-state trading of electricity, if considered necessary;

- Advise the state government on all or any of the following matters, namely:

- The State Commission shall ensure transparency while exercising its powers and discharging its functions.

- In discharge of its functions, the State Commission shall be guided by the National Electricity Policy published under sub-Section(2) of Section 3.

Appendix 28.3

State-Wise Reforms and Restructuring

Andhra Pradesh

- State Reforms Act came into force with effect from 1 February 1999; MOU signed with Government of India

- APSEB was unbundled into Andhra Pradesh Generation Company Ltd. (APGENCO) and Andhra Pradesh Transmission Company Ltd. (APTRANSCO for transmission and distribution)

- Andhra Pradesh Electricity Regulatory Commission was operational w.e.f. 3.4.1999; two tariff orders issued

- Obtained World Bank loan of US $210 million under the Adaptable Programme Loan (APL)—1 w.e.f. 22 March 1999 for reforms and restructuring

- And also DFID’s 28 million UK Pound as technical cooperation grant

- CIDA is giving technical assistance of Canadian dollar 4 million.

Arunachal Pradesh

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC was constituted

Assam

- SERC constituted, functional

- Tariff Order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Bihar

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC constituted

- Anti-theft law passed.

Chhattisgarh

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC constituted.

Delhi

- SERC constituted, functional

- Tariff order issued

- Reform law enacted

- DVB unbundled

- Distribution privatized.

Goa

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC constituted.

Gujarat

- MOU signed with Government of India

- State Reforms Bill enacted

- SERC became functional w.e.f. 10 March 1999; tariff orders issued

- Anti-theft law enacted.

Haryana

- MOU signed with Government of India

- State Reforms Act came into force w.e.f. 14 August 1998

- SERC became operational w.e.f. 17 August 1998

- Haryana SEB was unbundled into Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Ltd., a Trans Co. (HVPNL) and Haryana Power Corporation Ltd. on 14 August 1998

- Two Government owned distribution companies, viz. Uttar Haryana Bijli Vitaran Nigam Ltd. (UHBVNL) and Dakshin Haryana Bijli Vitaran Nigam Ltd. (DHBVNL) have been established. These two companies are expected to operate as subsidiaries of HVPNL, until they become independent licensees

- World Bank loan of US $600 million is available under succeeding APLs. The works under the first APL of US $60 million have been completed

- DFID’s technical co-operation grant of UK Pound 15 million is available for reforms works.

Himachal Pradesh

- SERC constituted functional

- Tariff order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Jammu and Kashmir

- Reform Bill passed by state assembly

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Jharkhand

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC notified

- Tariff order issued.

Karnataka

- State Electricity Reforms Act came into effect from 1 June 1999

- Two new companies namely Karnataka Power Transmission Corporation Ltd. (KPTCL) and Visvesvaraya Vidyut Nigam Ltd., a GENCO, (VVNL) were incorporated and came into existence as on 1 August 1999

- KPTCL has carved out five regional business centres (RBCs) for five identified zones

- SERC has been functional since 15 November 1999; tariff order issued

- State government has signed a MoA on 12 February 2000 with the Ministry of Power, Government of India (GOI), charting out the actions to be taken towards power sector reforms in a structured and time bound manner

- Anti-theft law passed

- Steps have been taken for the completion of privatization of distribution, one of the main points of MOA.

Kerala

- State government signed a MoA with the Ministry of Power, Government of India, in August 2001, agreeing to power sector reforms

- Central government has agreed to sanction Rs 150 crores for electricity sector reforms.

- KSEB was divided into three profit centres for generation, transmission and distribution in April 2002

- SERC constituted. Tariff order issued

- Anti-theft law passed.

Madhya Pradesh

- Reform law enacted.

- SERC has been operational since 30 January 1999. Tariff order issued.

- State government signed a MoA on 16 May 2000 with the Ministry of Power, Government of India (GOI), charting out the action to be taken towards power sector reforms in a structured and time bound manner

- SEB unbundled

- Anti-theft law passed.

Maharashtra

- SERC has been functional w.e.f. 6 October 1999. Tariff order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India

- Anti-theft law passed.

North Eastern States

- North eastern states have shown willingness to constitute Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission (JERC)

- Mizoram and Manipur are in the process of constituting.

Odisha

- The first state to undertake reforms back in 1996 through State Reforms Act. Also the first state to privatize distribution w.e.f. 1 April 1999

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SEB unbundled

- OERC issued third tariff order in December, 1999, and revised tariff order w.e.f. 1 February 2000.

Punjab

- SERC constituted, functional tariff order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Rajasthan

- Reform law enacted

- SERC has been functional since 2 January 2000. Tariff order issued

- SEB unbundled

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Tamil Nadu

- SERC constituted, functional; tariff order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India.

Uttaranchal

- MOU signed with Government of India

- SERC constituted

- SEB unbundled

- Tariff order issued.

Uttar Pradesh

- State Reforms Act was enacted

- SERC is constituted, functional. Tariff order issued

- As per the decision of the Government of Uttar Pradesh (GoUP), the activities of generation, transmission and distribution of erstwhile UPSEB have been transferred to:

- Uttar Pradesh Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Ltd. (UPRVUNL)

- Uttar Pradesh Jal Vidyut Nigam Ltd. (UPJVNL)

- Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation Ltd. (UPPCL)-UPPCL took over the transmission and distribution functions of erstwhile UPSEB.

- The activities, assets and staff of erstwhile UPSEB have been transferred to the new companies

- A MoU between Government of India (GOI) and Government of Uttar Pradesh (GoUP) was signed on 25 February 2000 charting out the actions to be taken towards reforms in which GOI has committed to support the GoUP in R&M, transmission works, reforms studies, joint venture hydro projects, rural electrification and by way of additional central power allocation

- Anti-theft law passed

- GoUP has taken a bold step of writing-off of Rs 19,000 crores of liabilities of erstwhile UPSEB with a view to starting the new companies, created after unbundling, with healthy balance sheets

- Distribution business of Kanpur has been handed over to the Kanpur Electricity Supply Company (KESCO)

- Uttar Pradesh Electricity Regulatory Commission (UPERC) has conducted five open house discussions for formulation of a tariff procedure

- World Bank has sanctioned loan of US $150 million for power sector reforms

- UPERC is to get an assistance of US $150,000 from the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF), a facility established and funded by a number of bilateral and multilateral agencies and international agencies.

West Bengal

- SERC has been functional since 10 March 1999, tariff order issued

- MOU signed with Government of India

- Anti-theft law passed

- Re-organization committee set up to study the state power sector, has submitted its recommendations to state government

- The state government has set up State Rural Energy Development Corporation (WBREDC) as an independent company under the Companies Act to manage distribution for rural and agricultural consumer segments with assistance of rural Energy Co-operatives

- Consultants have submitted the final report of the tariff rationalization study, financed by PFC.

APPENDIX 28.4 Growth of the Indian Power Sector

| Installed capacity | Energy generated | |

|---|---|---|

| (Thousand MW) | (Billion kWh) | |

| 1950–51 | 2.3 |

6.6 |

| 1960–61 | 5.6 |

20.1 |

| 1970–71 | 16.3 |

61.2 |

| 1980–81 | 33.4 |

129.2 |

| 1990–91 | 74.7 |

289.4 |

| 2000–01 | 117.8 |

554.5 |

| 2004–05 | 137.5 |

680 |

| 2008–09 | 175 |

842.5 |

| Growth (times) | 76.1 |

127.65 |

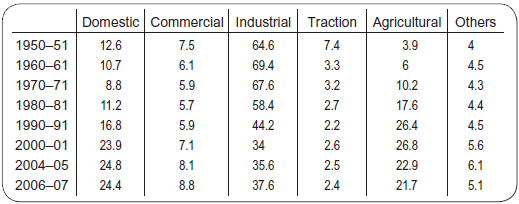

APPENDIX 28.5 Consumption in India by Sectors (%)

Source: Based on http://powermin.nic.in