23

Trade, Markets and Food Security in India: Issues and Prospects

C. S. Sundaresan* and P. V. Rajeev**

23.1 Introduction

One of the significant developments in the Indian food security front has been the initiation of the National Food Security Bill, 2010. It envisages establishing the scope of a conventional supply side management of the food sector, and therefore aims to provide subsidized food to all the poor. At the same time, it endorses the Rome declaration (at the World Food Summit, 1996) that the state reaffirms the right of everyone to have an economic and physical access to food—which is safe and nutritious. It seems that while the Rome declaration envisages a demand side management of food (market access), the Indian approach remains at its normal route for reasons perhaps known to everyone. There are, however, convincing arguments in India that the poverty estimates are not realistic and the people fitted above the line of poverty are also vulnerable, and that universalization of the right to food law will be required to meet the declared food security from the demand side, which will concentrate on the provision of employment (income) as a means to access food from the market. Therefore, the subject calls for attention from two angles, the establishment of sustainable agriculture and the food production systems (supply), and establishing market-driven food security systems, through the creation of income (employment).

A debate on the importance of agriculture, in a country’s economic development strategy, has a long history in economics. This discussion ranges from the Physiocrats of the 17th century to the later political economists like Ricardo, Malthus and Marx. It further extends to the 20th century economists, like Lewis, Kalecki, Jorgenson, Kaldor, etc. (1954–1976). A dichotomy of views, however, prevails in the contemporary debate over the role of agriculture and industry in the development of policy debate in the third world countries (Rao and Cabellaro, 1990). If there was an earlier consensus that a lack of growth in agriculture is a constraint to the non-agricultural growth, by the early 1980s it had vanished with the government emphasis on industrialization. The role of agriculture in the long-term development strategy, however, regained its momentum once again, by identifying its role in the international trade and as a source of domestic food security. This highlighted the supplementary and complimentary roles of agriculture, from an internal food security and global market perspective.

The role of agriculture in the long-term economic development of the South Asian economies, like India, has been emphasized for its food security and economic sustenance, from time to time. Many studies, which attempted to account for the disturbing trend in the industrial performance in India, for instance, were based on the proposition that the deceleration in the industrial growth during 1965–75 was related in a crucial way, to the performance of its primary agriculture sector. Further, it is observed that the adverse inter-sectoral terms of trade and movements have adversely affected industrial profitability, investment and hence macro-economic growth (Chakravarty, 1974; Mitra, 1977). The food grain crisis India faced in the 1960s, emphasized the importance of the sector and persuaded the new ways and means to enhance the agriculture sector in the national economy, from the food security point of view.

Before getting into the policy perceptions and macro-economic modalities, to achieve food security, it is worthwhile to know the balancing point where such a mechanism would not affect the overall economic performance. From an economic perspective, Kalecki (1976) argued that disproportionalities would arise whenever the agricultural supply growth falls below a certain minimum range needed to sustain a predetermined growth of the economy as a whole. It is because the excess demand for food (agricultural goods) exercises an upward pressure on the wage rate, relative to the prices of the manufactured goods, squeezing the industrial profitability and hence the investment demands in the industrial sector. Subsequent studies by Raj (1976), Nayyar (1978), Chakravarty (1979) and Sen (1981) observed that the economic growth and the industrial sector were constrained many a times by the traditional farm sector. The structural transformation of the economies often accompanies the enhanced production and the productivity levels, in varying degrees, in the different countries. Accordingly, its sectoral performance also undergoes changes. From the food security point of view, this structural transformation of the economic sectors and the production and productivity levels are very crucial.

23.2 Food Security: Concept, Definition and Constraints

Food security is broadly defined as a synchronization of three important elements. It envisages the availability of quality food at affordable prices to the citizens of a country, at any time and place. Hence it has three main elements to fulfil—the food availability, the quality of food available and the accessibility of the people to such food. It essentially refers, first of all, to the ability of a country to provide the required food to all its citizens. Second, it checks the capability of the domestic market and the supply institutions to ensure the quality of food and the stability of the food supplies. Third is the economic and physical ability of the population to obtain the necessary quantity of food, by the prevailing food distribution system. Conceptually, therefore, food security has to foster a situation where everyone has access to quality food, at all times, and at affordable prices. At the household levels, food security implies having physical and economic access to food that is adequate, in terms of the quantity, quality and safety. The access to food is determined, however, by the food entitlements. This entitlement is the sum of the human, physical and financial assets that an individual or a household owns, and can be used to acquire food. The rate, at which these assets can be converted to food, is either through exchange (value) or production (value) (Sen, 1981; Jha, 2000). What it implies is that food security concerns the physical and financial aspects of the food entitlements in terms of security, at the individual and household levels. In other words, it means that the regional or national food production levels and food stocks need not necessarily lead to an individual or household food security.

TABLE 23.1 Dimensions of Food Insecurity

| Transitory | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|

| Household level | Shortfall of income and savings. | Insufficient assets (including education and human capital) intra household resource sharing. |

| Market level | Change in the prices of food. Decline in the availability of food. | Long-term relative prices and level of wages. |

Irrespective of the high food availability, the accessibility to quality food has often been identified as a major source of food insecurity. Hence it calls for the simultaneous improvement in the output levels, as well as the distribution infrastructure. The other option in a market-driven economy, has been, to improve the income level of the people (through provision of employment), which enables them to access food at the market-determined prices. Food security, therefore, has the following dimensions at the household and market levels. It explains that food insecurity can either be transitory or chronic. In the transitory case it can be, for example, the temporary inability to acquire sufficient food. But in chronic food insecurity, it is the long-term inadequate ability to acquire sufficient food (Table 23.1).

23.3 Food Security in South Asia: A Macro Overview

The status of food deprivation for India and other South Asian neighbours (Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) is not encouraging. The depth of hunger measured by the average dietary energy deficit of the under-nourished people in the four South Asian countries (in terms of kilocalorie) stands at Bangladesh 340, India 290, Pakistan 290 and Sri Lanka 260 (the bigger the figure, the deeper the hunger). The role of the enhanced agricultural activities and the improved food distribution systems in these economies, therefore, are identified as being of vital importance. It may be relevant to mention in this context that from a historical perspective, few countries have been able to successfully transform their national economies into a developed one without achieving a reasonable level of food security and a developed agricultural sector (FAO, 1999). In tune with this understanding, the domestic support to agriculture has been continued as a source to strengthen the primary/core sector of many Asian economies. They, however, are yet to reach the desired level of growth in the farm sector, achieve the reasonable level of food security to the citizens or gain a significant share of the global market for the agricultural commodities. Table 23.2 conveys the per-capita food production, food imports, food aid, etc. at a constant term for the severity of the problem.

TABLE 23.2 Food Security Index: South Asia

Source: United Nations, Human Development in South Asia, 2000.

There are diverging views, however, on the scope and prospects of the farm sector in different countries for food security, with the ongoing structural adjustments and trade liberalization. The post-independence economic growth and development of South Asia was almost centred on agriculture and food production. With the sound macro-economic thrust—massive public investments in the agricultural infrastructure, the R&D, the credit and technology—many of the regional economies succeeded in achieving a desirable level of food security. In some cases, for instance, India’s food production has doubled, since the Green Revolution in the early 1960s. Against the domestic food security ideal, as a result, some of the countries in the region have been net exporters of food. If around 50 per cent of the population in South Asia remained below the poverty line in 1960s, now it is estimated at around 30 per cent.

23.4 Consumption Patterns and Indian Food Security

India is the second largest producer of rice, and ties with the United States as the second largest producer of wheat. In milk production, India enjoys the first position. Yet, behind these achievements lurk more disturbing trends—the production and the consumption of the important protein-rich items, like pulses, have been unsatisfactory. From 1960 to 1995, the per-capita supplies from all plant products increased modestly from 47.3 to 48.7 gms per day. The supplies of the critic amino acid protein availability have fallen from 9,384 to 8,790 milligrams per day. The contention is that more than half of the country’s population is short of the energy requirements, and three-quarters do not meet the minimum protein requirements. Around 624 million Indians still remain malnourished (Runge and Senauer, 2000).

TABLE 23.3 Production of Food Grains in India (in Million Tonnes)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2003.

The total food grains production in the country increased from 50.82 million tonnes in 1950–51 to 196.81 million tonnes in 2000–01. Today, the country is virtually selfsufficient in the production of food grains. Despite the fact that the country experienced a rapid rate of population growth, of about 2 per cent per annum, we could maintain the rate of growth of the food grains production at a level which was above the rate of population growth, and thus ensure an increase in the per-capita production of food grains.

While the total food grains production increased almost four-fold between 1950–51 and 2000–01, the production of wheat increased 10-fold during the period, as can be seen from Table 23.3. The production of rice increased four-fold during the 50-year period, while that of coarse cereals doubled during the period. An increase in the production of pulses was, however, less impressive.

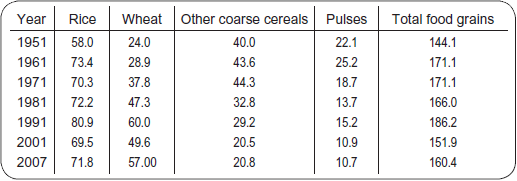

Table 23.4 shows the data on per capita net availability of food grains in India during the period 1950–2001. The table shows that the per capita net availability of rice increased by 20 per cent during the period, while in the case of wheat it has doubled. However, there was a consistent decline in the net per-capita availability of the coarse cereals and pulses.

The main vehicle, through which the government encourages the farmers to increase agricultural production, is through its food procurement operations at the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) announced from time to time. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) recommends the prices for various agricultural commodities. In its recommendations, the CACP takes into account not only a comprehensive overview of the entire structure of the economy and the details relating to a particular commodity, but also a number of other important factors. This is reflected in the list of factors that go into the determination of support prices—the cost of production, changes in the input—output prices, the open market prices, the demand and supply, the inter-crop price parity, effect on the industrial cost structure, the general price level, the cost of living, and the international price situation. Based on the recommendations made by the CACP, the government announces the MSP. The objectives of the price policy are two-fold—(1) to assure the producer that the price of his produce will not be allowed to fall below a certain minimum level, and (2) to protect the consumer against an excessive rise in prices.

TABLE 23.4 Per-capita Net Availability of Food Grains in India (Kgs/Year)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2008.

Dramatic changes in the food consumption patterns have taken place in the urban and rural India, in the post-Green Revolution years (Meenakshi, 2001). For instance, the rural cereal consumption at all India level had declined from 15.3 kg monthly per capita in 1972–73 to 13.4 kg monthly per capita in 1993–94. Similarly, in the urban areas, this decline is from 11.3 to 10.6 kg monthly per capita. On the other hand, the consumption of protein-rich food items like milk, milk products, meat, etc., has found more place in the consumption basket. This trend of food diversification has been registered not only among the affluent sections of the population, but among the poorest 25 per cent of the population as well (Planning Commission, 2001). Hence, the shift in the emphasis of crops, under the government support programmes, needs change from time to time towards achieving food security from a definitional point of view.

It is, however, not sure whether the change in the consumption basket of the people is induced by their income and life styles, or on the basis of their accessibility to such food items. Irrespective of it, given the nature and structure of the consumption preferences and the choice of food by the masses, the entitlements may vary from time to time. It becomes essential in such situations, to estimate the farming patterns and the new food production levels, varying levels of incomes and hence the new food entitlements in the short and long run towards establishing a food secure nation. There are various projections and forecasts on the food production and food availability levels in India, in the medium and longer term. Under a scenario of 5 per cent growth in the GDP, one estimate suggests that the domestic demand for food grains in India by 2020 would be 201 million metric tons (Rosaiah, 2000). The UN estimate, rather than projecting a particular food requirement figure, proposes the probable means and approaches to reach a near accurate projection of the food requirement. It relates the growth in population and the productivity levels, to reach such a figure. Accordingly, it projects India’s population to be at 1301.1 million by 2020, and suggests that the supply projections of food, under the assumptions of the input—output prices and the total factor productivity, would be more authentic. This would be capable of projecting the probable level of food supplies in the country, under (1) sustained growth in productivity at the levels prevailing in the 1980s, through a recovery in the public investment and (2) continued reduction in the productivity levels, owing to the further slowdown in public investment. With the level of population expected and the productivity levels, as suggested in the above alternatives, the following demand and supply projections are worked out for 2020 in India (Table 23.5).

TABLE 23.5 Long Run Demand-Supply Gap of Food Grains (Cereals) in India

Source: FAO, Food and Agriculture Statistics (Various Issues).

This does not necessarily ensure the accessibility of the people, to food or their food entitlements. Rather, it is just an indication of the minimum food requirement, if other criteria are fulfilled. However, the two agents, which work in enabling food security in a system, are the market (based on demand supply norms) and the government (sponsored food distribution schemes), with different sets of inputs and ingredients.

23.5 Public Distribution System and Indian Food Security

It is now recognized that the levels of food production, the stock of food material or the food market is not a sufficient pre-condition to establish the food security in a country. Also, it is true that the establishment of a food security through the mediation of market needs more economic and employment avenues. Hence, the Public Distribution System (PDS) works as the most important and vital source of ensuring food access to the consumers in the Less Developed Countries (LDCs) like India. With a network of more than 4.62 lakh fair price shops, distributing the consumption items worth more than Rs 30,000 crores, to 16 crores families, the PDS in India is the largest distribution network of the sort in the world. None, however, believes that everything is fine with the PDS system, either in the efficiency of its food distribution or its viability for long-term sustenance. It involves a huge expenditure in the form of annual food subsidy. This subsidy is on the increase every year, despite the improvement in the growth and employment levels. It increased from Rs 2,450 crores in 1990–91 to 25800 crores in 2004–05, constituting an average 5.40 per cent of the total annual government expenditure (Table 23.6).

Is there really any relation between the food stocks, the food grain procurement and the supply of it through the PDS? The recent experiences suggests ‘no’ as an answer. There are wide variations between the production, procurement and distribution quantities of the food material in India, across the years. For example, the production of rice, which was increasing at the rate of 3.48 per annum in the 1980s, increased only by 1.87 per cent in the 1990s. The rate of growth of wheat in the same periods was 4.38 and 3.21 per cent, respectively. The procurement of wheat accelerated, at an annual compound rate of 3.65 per cent in the 1980s and 9.64 per cent in the 1990s; while that of rice increased at 5.5 per cent, during these two decades. In absolute terms, the Food Corporation of India’s food grain procurement had been increasing at a moderate pace of 4 to 13 million tonnes, during the 1960s and the 1970s. The procurement rose faster, though with year to year variations, to reach 24 million tonnes by 1990–91 and more than 40 million tonnes in 2000–01.The disposal of food grains through the PDS, which reached a peak of over 26 million tonnes in 1996–97, plummeted to 13.6 million tonnes in 2001–02, and rose again to 23.9 million tonnes in 2003–04.

TABLE 23.6 Food Subsidy of the Central Government

| Year | Amount (in Crore Rupees) | Percentage of total government expenditure |

|---|---|---|

| 1990–91 | 2450 |

2.33 |

| 1991–92 | 2850 |

2.56 |

| 1992–93 | 2785 |

2.27 |

| 1993–94 | 5537 |

3.90 |

| 1994–95 | 4509 |

2.80 |

| 1995–96 | 4960 |

2.78 |

| 1996–97 | 6066 |

3.19 |

| 1997–98 | 7500 |

3.34 |

| 1998–99 | 8700 |

3.30 |

| 1999–2000 | 9200 |

3.09 |

| 2000–01 | 12,010 |

3.69 |

| 2001–02 | 17,494 |

4.83 |

| 2002–03 | 24,176 |

5.84 |

| 2003–04 | 25,200 |

5.31 |

| 2004–05 | 25,800 |

5.40 |

| 2005–06 | 23,077 |

5.30 |

| 2006–07 | 24,014 |

5.50 |

Source: Economic Survey (Various Years).

One of the most interesting queries at this point has been: What is the ideal food stock level India needs to maintain, towards ensuring the essential food distribution as well as enabling the efficiency of the food distribution network? Prof. Krishnaji (1988) suggests that the buffer stock of food grains should be an ‘optimum stock’ that is not ‘economically crippling’. Statistically, this is a quantity that is equivalent to the population-adjusted standard deviation, from the mean output of an appropriate historical time period. Taking the net domestic production and the population levels of 1968–84 (as base), he arrived at 13 million tonnes, as enough buffer stock to cover the unforeseen shortages and ensure the availability of food material, to be distributed through the PDS. If we consider the requirement of stocks to keep up a per-capita supply of 452 gms per day, for the total population of 2001 (1027 million), the figure would be around 14 million tonnes. If the subsequent increase in population is considered for estimation, the stocks will have to rise slightly every year. However, if the fluctuations in the production and procurement are reduced, then the quantity requirements will come down. The report of the working group on the PDS and the food security for the Tenth Five Year Plan, has made the following suggestions to restructure the PDS in India:

- The items other than rice and wheat need to be excluded from the purview of TPDS. The main objective of providing food subsidy to the poor is to ensure food security. The provision of food subsidies should be restricted to these two commodities.

- The items such as sugar should be kept outside the purview of PDS. Sugar should be decontrolled, and the system of levy on sugar should be discontinued.

- The average shelf life of the coarse grains is limited, making them unsuitable for the long-term storage and distribution under the PDS. The inclusion of the coarse cereals under the PDS cannot be taken up as a national level programme, since there is no standard variety of the coarse grain. But the initiatives from the side of the state governments are possible catering to the needs of the specific localities.

- The kerosene oil is also a commodity supplied through the PDS and intended for the poor. But this is an item where there occurs large-scale illicit diversion, because of the wide price margin in the PDS and the open market. The non-poor very often corners the subsidy on kerosene, and uses it for adulteration with diesel. It is irrational, therefore, to continue to subsidize kerosene, at rates that are so high, and continue its distribution through the PDS. The subsidy on kerosene should be gradually phased out by raising its supply price under the PDS, and an alternate means of distribution of this commodity to the poor should be explored. The introduction of fuel stamps for the distribution of kerosene to the poor could be considered.

- All further attempts to include more and more commodities under the coverage of the food subsidy, should be resisted.

23.6 Multilateral Trade and National Food Security

Following the GATT, the WTO initiative for entertaining the bids and offers to reach the mutual concessions on the trade of the agricultural commodities, internationally, there are concerns over the prospects of a market-led food security scenario emerging in the developing countries. This concern gets more aggravated, while knowing the fact that the WTO regime would resort more to a mutually managed mercantilism than realizing from the neo-classical doctrine of free trade. For the first seven rounds of the GATT, agriculture remained off the table. This was at the behest of the Americans and the Europeans, who felt it too sensitive to be placed among the disciplines of manufacturing. It more importantly was reflected on the agriculture export subsidy wars of the 1980s, to clear the European commodity surpluses. Throughout the Uruguay round, the European agricultural interests supported the American NGOs that would do their bidding, arguing that free trade harmed the US farmers, as well as the European ones (Runge et al., 2000). Though Europe could have come close to a settlement after exhausting its huge surplus stocks, the US farming interests supported the expanded US agricultural exports.

Simultaneously, however, the environmental issues began to emerge in the trade issues. The environmentalists established linkages with trade from a burgeoning perception that growth through trade would undermine the environmental quality, which in turn will lead to a worldwide ‘race to the bottom’. Also, it saw an opportunity for the optimistic environmental groups to raise their voice over the need to protect the environmental resources. None, however, dealt explicitly with the new trade-affected agriculture or food security, until the emergence of the GM debate (see Section 23.7).

From a global food security perspective, it is generally agreed that the international trade in the agricultural commodities needs to be liberalized, and the price instability generated by the tariff distortions are to be minimized. In this regard, the big demand is the dismantling of the protectionist regimes in the United States and the EU, which may improve the market access and competitive advantage of the LDCs. It is estimated in this context that market access and competition would do more good to the developing countries, than what the food or other sorts of aid they get currently from the developed world. For example, a 9–10 per cent increase in the market access to the US sugar markets, for the Caribbean producers, would do more to raise the incomes in the Caribbean basin, than has all the development assistance provided in the last 25 years.

From an international outlook, there are estimates which suggest that the food deficiency in nations in the South Asian region will be very high by 2020. In other words, trade in the essential food commodities would be the source of mitigating the food deprivation in many of these countries. Therefore, a market-led food security in the world requires dynamic steps in the form of more market access to the developed countries, and a spontaneous flow of the food trade without any distortions and aberrations. The FAO projects the following long-term food products availability and requirements, for the gap estimation in the South Asian subcontinent (Table 23.7).

With the given definitional constraints (Section 23.2), coupled with an unbalanced food sector and low growth in employment (income) in the subcontinent; even if the markets are opened up for free trade, its scope of bringing in a desired food security scenario is limited (or unlikely). The threat of the market distortions and the resultant national implications (political and economic) on the other hand, however, become new issues to tackle with. The reciprocal concessions and the balanced trade packages would, therefore, be only a short-term strategy to end the price instability, generated by the tariff distortions from such an open market. Progress must hence be made towards the increasing market access and the reduced export and production subsidies, to make the competitive advantage of food products on an equal footing. However, to assure the LDCs of their fear of the market forces, proper rules needs to be in place to provide the guaranteed access to food in times of exigencies. Proposals are there in this regard, to establish a multilateral grain sharing agreement that guarantees emergency concessions. The government and the private sector, perhaps, must make a collective initiative in this and survive the grey areas still prevailing in the global agricultural trade. The forthcoming rounds of multilateral trade negotiations in the agricultural commodities, therefore, carry much weight from a global food security angle.

TABLE 23.7 Estimates of Food Shortage in South Asia by 2020

All the quantities are in 000 tones unless mentioned otherwise.

Source: FAO, Food and Agriculture Statistics (Various Years).

The estimates, however, are that the agricultural trade liberalization is likely to negatively affect the rural and the urban poor, in the less developed world, in various forms. For instance, exposing small farmers in the developing countries, to import the competition, can lead to the erosion of the farming activities which, in turn, increase the longer term dependence on the global market for national and local food security. On the other hand, raising the food prices to control the imports can lead to an imbalance in the farming activities, which further benefit the competitive advantage of the importers in the long run, for the specific basket of commodities. The safety-net measures like employment programmes and the targeted food subsidies are nothing new to try within the developing world. The inclusion and exclusion constraints of the targeted PDS in many of the countries have been in debate for its suitability to ensure the food accessibility to the people. It is, however, a relief that some countries in the region (like India) can combine its buffer stock operations with a liberal regime to pursue a programme of food price stabilization. From an export-oriented growth perspective, exercising this right may be useful for improving the market competitiveness. Its ability to quench the hunger, however, is not yet clear. Suggestions, therefore, are that the country has to retain its right to levy an export duty on the commodities, in which it has a market power (competitiveness). This may facilitate the financing consumption subsidies that are essential to ensure food security to the poor. It may further help in aligning the tariffs that have been bound at very low levels. Synchronization of the market prices and the domestic food supplies, hence, remain as a grey area—yet to be worked out for solutions.

Another outlook from the market angle includes improving the nation’s access to cheap food, from competitively advantageous countries. It would be more efficient and cheaper, as compared to striving for the internal self-sufficiency. This argument holds the view that trying to produce all what the population needs, regardless of the cost and the natural resource endowments, may not be feasible and sustainable. What is required is a market for food materials, where it can be transacted transparently—a sound tariff and the market management system. The irony, however, is that even if the countries could benefit unilaterally, by opening up domestic markets, most of them believe that no country should disarm unless and otherwise other countries make matching concessions. It is, therefore, timely to evolve a suitable food security strategy for the national economy to move with the current economic and market trends, domestically and globally.

23.7 Market, Prices and Food Security

The mechanism to determine the price of food material in the domestic market is significant in determining the domestic food security or insecurity (accessibility criterion), in the south Asian region. Currently the international trade in food articles is administered (if not banned) in varying degrees in the individual countries of the region. This is in continuation of the post-World War II government policy, of stressing self-sufficiency in food grains. In the times of food scarcity and exigencies, the government agencies decide on the quantity of imports and adjust the exports accordingly. As the agreement on the market access, export competition and domestic agricultural supports have been reached; however, to determine the impact of prices of the major food grains is an issue to be addressed. Within the perceived definition of food security, the prices play a vital role in achieving the food accessibility component in the different countries of the sub-region. In a market-driven food supply system, the income and price elasticity of demand play a crucial role in fulfilling the role of markets in achieving food security. The income—price elasticity of demand, for the food material in the south Asian region, is discussed as follows.

Irrespective of the export and import regimes, generally, there have been two heterogeneous groups in each economy—the households that are net consumers of food and the households that are net producers of food. The relationship between the income and consumption expenditure, however, remains similar for both the categories (Broca, 2000).

(where w = wage, r = rent, a = income from agriculture or business and e = other exogenous income).

(where dY = change in income, c = consumable income, x = expenditure, dP = change in food price).

The simple conclusion in a closed economy framework, therefore, is that a price increase in the market (ceterus paribus) brings in a net consumer loss and a net producer gain. The size and proportion of the net consumer and producer gain, in a given economic set-up, further has the potential of determining the price effect (or real income effect) and hence on food security. Research from India (Broca, 2000) reveals substantive evidences to the effects mentioned above. For instance, almost all the consumers in the urban areas are net consumers of food. Among the rural population, almost 50 per cent are net consumers as they are landless or marginal landholders. It is estimated that if India were to harmonize its wheat prices, with the world’s market prices, the prices are likely to rise by Re1 a kilogram. Taking an average 400 kg consumption of wheat and flour by a poor Indian household, this translates to a money loss of Rs 400 per year for an individual household (Broca, 2000). With a constant real income, the implication of price increase on the food accessibility and food entitlements, therefore, will have its deleterious reflections on the national food security scenarios. Currently, the deleteriousness of these implications is not felt, perhaps because of the administered market prices of food materials or the real income compensating mechanisms existing. The economic counter-argument for a market-led food security, and thereby the consumer welfare, is yet to be confirmed. There are arguments from the theoretical perspective, however, that higher prices result in increased profitability, which in turn lead to higher productivity and wage. The rise in the real wage is hence likely to take care of the price effect (Stolper—Samuelson theorem). In the short run, however, this could bring in a negative impact on the real wages and hence individual food security.

Attempts are on, however, to explain the prospects of positive and negative implications on the food security, out of the higher market prices of the food material. The application of Ricardo-Viner model (Broca, 2000) with the two sectors, where each good is produced with labour and one sector specific factor of the production, reveal the following scenario. The equilibrium is derived at a point where the wages in each sectors are equalized. If the wage (w) initially is lower in either of the sector, the labour will flow to the other. As a result ‘w’ will reduce in the later sector and increase in the former, causing for the marginal physical product to go up, given a constant price. This equilibrium is achieved with Constant Returns to Scale (CRS) technology, used in the manufacturing sector and the diminishing returns to labour in each sector. The Haberler theory suggests that if the food prices increase in the domestic market, the food output would go up and the real wage falls in terms of food and rises in terms of other commodities (ceterus paribus). It is logical, therefore, that with a pool of unemployed or underemployed workers, the nominal and real wages may fall sharply in terms of food. The gainers in this trade-off would be the owners of the sector-specific factors in food industry, as each unit of this sector specific-factor has more labour to work with, for its marginal physical product to go up along with an increase in the food price. However, if there is a constant return to scale and the factors of production are paid by their Value Marginal Product (VMP), the Euler’s theory guarantees zero profits in food production.

The Hecksher-Ohlin—Samuelson theory treats both the factors mobile between the sectors. As a result when the food price rises, the food production becomes more profitable, the food output expands and the factors of production have to move from other sectors to the food industry. The food industry being labour intensive, comparatively, the price of labour has to be risen relative to the price of the capital. If the elasticity of substitution between labour and capital is high in the other sectors, as compared to the food sector, and if it is relatively easy to substitute the capital for labour in the opposite sector, the capital can substitute labour and output in the other industries need not be down as a result of the labour outflow from that sector,as a result of the increased food prices and the resultant wage increase to labour.

The crucial difference between the models (two sector-two commodity), explained above, has been in their treatment of the factor mobility across sectors and boarders. Also, it undermines the substitution of the factors of production. For example, land cannot be transformed into machinery, but can be sold, and the sales proceeds be used to buy machinery (technology). Therefore, full factor mobility and substitutability is appropriate in the long run. The treatment of the technological process in the post-Keynesian economics (Robinson, 1956), on the other hand, suggests that it is entirely endogenous. Technological change and innovation is seen as the result of entrepreneurial initiative, and the drive to search for cheaper and more efficient production methods. It is also argued (Kaldor, 1960; 1966) that technological progress is both the case and the result of growth in the specific economic sector.

On the demand side (Keynesian effective demand and Ricardian reciprocal demand), it can logically be derived that with a price increase in the food sector wages are unlikely to increase. To avert the higher labour cost, technology and capital (like GM seeds, etc.) may be tried to substitute the labour. There, however, is no problem of aggregate demand, since the investment adjusts the product market. The marginal propensity to save out of the wage being zero (Kaleckian assumption), the future reciprocal demand for the food material by the working class is not expected to grow. Therefore, the demand management arising from the international intervention, affecting the primary commodity prices, need clear theoretical understanding for the third-world countries to work towards their food security or insecurity from a global market, as it can have its ramifications on the overall economy and sectors. A beginning in this direction has already been made by Kalecki (1976), Thirwal (1980), Beckerman et al. (1986). The substitution of labour with the capital, in the food sector, has the following link effects in monetary terms:

This in turn can lead to

low interest rate → high investment → high level of non-farm activities → development/underdevelopment path. (4)

The estimate of these impacts, in terms of the real welfare effect in different regions of the world with the liberal trade in food material, is given in Table 23.8.

TABLE 23.8 Welfare and Supply Effects of Trade Liberalization on World Food Markets

* South Asia comprising India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Source: FAO, Food and Agriculture Statistics (Various Years).

23.8 Conclusion

Though agriculture remains the significant contributor to the GDP, and the sector absorbs a chunk of the labour force, India is still in the grip of food insecurity in varying degrees and in different locations. Definitional constraints more often strain the national government to establish a food security scenario, even with a comfortable national or regional food production (supply). The scope of the market forces, to establish the desired food security at a macro level, is not confirmed yet as the necessary economic equilibrium and the distributional efficiencies are not reached. Further in the absence of the effective and reciprocal demand, the substitutability of labour with capital or technology (the globalization effect) in the domestic farm sector of the Indian economy seems to be unviable. The sponsored PDS hence remains as the most reliable source to achieve a reasonable level of food distribution, while leaving the desired food security level a distant dream.

The scope of a multilateral trade-led food security in India may not be sustainable, till the establishment of the internal market mechanisms to stabilize the food prices. Technology being treated as an exogenous variable in the domestic food production, the scope of global food markets is doubted for its potential in mitigating the domestic food security concerns. Broadly, the major factors, which influence such a prospect are (1) the size and nature of the existing and emerging net trade, (2) WTO tariff and non-tariff commitments and (3) the progress in the implementation of these commitments. The trade forecasts (IFPRI) for 2020 suggest that the net trade in most of the food commodities in countries like India may be negative in the long run. This implies a reasonable dependence on the imports for the domestic food security. The threat of the market distortions, and its domestic political and economic implications, are foreseen as new issues (political) for the national economy to tackle. Keeping this in mind, one strategy may be to evolve a sustainable market-driven farming approach to prosper with the liberalization drive and the economic growth initiative with the food security. This becomes more sensible when the subsidies cannot sustain as a source of growth.

References

Anderson, K. (1992). Effects of environment and welfare of liberalising world trade: The case of coal and flood. In K. Anderson and Blackharst (Eds.), The Axing of World Trade, Harvester Wheatsheaf, New York.

Biles, J. J., and Pigozzi, B. W. (2000). The interaction of economic returns, social structure and agriculture in Mexico. Growth and Change, 31(1), Winter.

Broca, S. S. (2000). Country paper—India 1. In International trade andfoodsecurity in South Asia. Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organization.

Brown, L. A. (1998). ‘Reflections on third world development: ground level reality, exogenous forms and conventional paradigms. Economic Geography, 64.

Brown, L. A. (1991). Place, migration and development in the third world. London: Routledge.

Chakravarty, S. (1974). Reflections on the growth process in the Indian economy. Lecture at the Administrative Staff College of India, Hyderabad.

Chakravarty, S. (1987). Development planning: The Indian experience. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Choudhari, E. U., and Hakura, D. S. (2001). International trade and productivity growth: Exploring the sectoral effects for developing countries. IMF Staff Papers, 47(1).

Cox, A. M., Alwang, J., and Johnson, T. P. (2000). Local preferences for economic development outcomes: Analytical hierarchy procedure. Growth and Change, 31, Summer.

Dutt, A. K. (1991). Stagnation, income distribution and the agrarian constraint: A note. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 15.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Food and Agriculture Statistics (various issues) FAD, Rome, www.faostat.com.

Government of India, (1999 and 2003). Agricultural Statistics at a Glance. New Delhi: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture.

Jayasuriya, K., and Rosser, A. (2001) Economic orthodoxy and East Asian crisis. Third World Quarterly, 22(3), June.

Jenson, B., and Glasmeier, A. K. (2001). Restructuring Appalachian manufacturing in 1963–92: The role of branch plants. Growth and Change, 32, Spring.

Jha, S. C. (2000). Trade liberalization andfood security in Asia. Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organization.

Jorgenson, D. W. (1967). Surplus labour and development of a dual economy. Oxford Economic Papers, 19, November.

Kaldor, N. (1967). Strategic factors in economic development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kalecki, M. (1976). Essays on developing economies. Hassocks: The Harvester Press.

Krishnaji, N. (1988). Foodgrain stocks and prices in economy, society and polity: Essays in the political economy of Indian planning. A. K. Bagchi (Ed.), Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Kruger, A. (1978). Foreign trade regime and economic development: Liberalization attempts and consequences. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Kumar, A. K. (2001). The price of reforms. Frontline, 21 December.

Lavoie, M. (1995). The Kaleckien model of growth and distribution and its neo-Ricardian and neo-Marxian critiques. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19, 789–818.

Meller, J. W., and Lele, U. (1973). Growth linkages of the new food grain technologies. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 28.

Meenakshi, J. V. (2001). The public distribution system in the context of changing food consumption trends: A review of the evidence. Report prepared for the Planning Commission, Government of India.

Mitra, A. (1977). Terms of trade and class relations. An essay in political economy. London: Frank Cass.

Nair, K. N., and Sundaresan, C. S. (1997). Political economy of member control in cooperatives: A case study of dairy cooperatives in Kerala. In A. Dubey (Ed.), Democratic governance and Indian cooperatives. Delhi: Kalinga Publications.

Nayyar, D. (1978). Industrial development in India: Some reflections on growth and stagnation. Economic and Political Weekly, 13, 31–33, August.

Paarlberg, R. (2000). The global food fight. Foreign Affairs, 79(3).

Pender, J. (2001). From structural adjustment to comprehensive development framework: Conditionality transformed? Third World Quarterly, 22(3), June.

Planning Commission. (2001). Report of the Working Group on Public Distribution System and Food Security for the Tenth Five Year Plan, New Delhi, Government of India.

Pronk, J. P. (2001). Aid as a catalyst. Development and Change, 32(4).

Raghavan, M. (2003). Food stocks: Managing excess. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(9), March 1.

Raj, K. N. (1976). Growth and stagnation in industrial development. Economic and Political Weekly, 11.

Rajeev, P. V. (1997). Poverty and food security in India. Southern Economist, 15January.

Rao, J. M., and Caballero, J. M. (1990). Agricultural performance and development strategy: Retrospect and prospect. World Development, 18(6), June.

Robinson, J. (1956). “The accumulation of capital.” London: MacMillan.

Rosaiah, D. C. (2000). International trade and food security in Asia. India, Country paper no. 2, Asian Productivity Organization.

Rosengrant, M. W., Paisner, M. S., Meijer, S., and Witcover, J. (2001). Sustainable options for ending hunger and poverty: Global food projection to 2020. Emerging Trends and Alternative Futures. International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI, August.

Runge, F. C., and Senauer, B. (2000). A removable feast.’ Foreign Affairs, 79(3).

Sen, A. C. (1981). Poverty and famine: An essay on entitlements and deprivation. Oxrord: Calrendon Press.

Sen, A. (1991). Shocks and instabilities in an agriculture constrained economy: India 1964–85. In J. Breman and S. Mundle (Eds.), Rural Transformation in Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sundaresan, C. S. (2001). Impact of multilateral trade on dairy commodity markets in LDCS: Recent evidence from Delhi. Economic and Political Weekly, 36(34) 25 August.

Sundaresan, C.S. (2000). Economics of water markets: Towards a policy option. Productivity, 41(3), October—December.

United Nations. (2000). Human development in South Asia. Oxford University Press, New York.

Waqif, A. A. (2000). India’s role in economic development of SAARC countries. In A. N. Ram (Ed.), India’s pivotal role in South Asia: Optimizing benefits and minimizing apprehensions. New Delhi: Coalition for Action on South Asian Cooperation, India Chapter.

World Bank. (1990). World Development Report, Oxford. University Press, New York.

World Food Programme. (2001). Food insecurity atlas of rural India. M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai.