4

NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Needs Assessment includes the processes used to analyze a current business problem or opportunity, analyze current and future states to determine an optimal solution that will provide value and address the business need, and assemble the results of the analysis to provide decision makers with relevant information for determining whether an investment in the proposed solution is viable.

The Needs Assessment processes are:

4.1 Identify Problem or Opportunity—The process of identifying the problem to be solved or the opportunity to be pursued.

4.2 Assess Current State—The process of examining the current environment under analysis to understand important factors that are internal or external to the organization, which may be the cause or reason for a problem or opportunity.

4.3 Determine Future State—The process of determining gaps in existing capabilities and a set of proposed changes necessary to attain a desired future state that addresses the problem or opportunity under analysis.

4.4 Determine Viable Options and Provide Recommendation—The process of applying various analysis techniques to examine possible solutions for meeting the business goals and objectives and to determine which of the options is considered the best possible one for the organization to pursue.

4.5 Facilitate Product Roadmap Development—The process of supporting the development of a product roadmap that outlines, at a high level, which aspects of a product that are planned for delivery over the course of a portfolio, program, or one or more project iterations or releases, and the potential sequence for the delivery of these aspects.

4.6 Assemble Business Case—The process of synthesizing well-researched and analyzed information to support the selection of the best portfolio components, programs, or projects to address the business goals and objectives.

4.7 Support Charter Development—The process of collaborating on charter development with the sponsoring entity and stakeholder resources using the business analysis knowledge, experience, and product information acquired during needs assessment and business case development efforts.

Figure 4-1 provides an overview of the Needs Assessment processes. The business analysis processes are presented as discrete processes with defined interfaces, although, in practice, they overlap and interact in ways that cannot be completely detailed in this guide.

KEY CONCEPTS FOR NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Needs Assessment processes guide the investment decisions made by organizations. During portfolio and program management, business analysis results are used to ensure that the performance of the portfolio or program continues to provide the expected business value; that new initiatives align with organizational strategy and portfolio and program objectives; that proposed portfolio components, programs, and projects are well vetted and scrutinized with accurate information; and that all aspects of a proposed solution are analyzed for value and risk. During project work, similar alignment activities occur to ensure that the initiative stays aligned to organizational strategies.

Needs Assessment activities are performed to assess the internal and external environments and current capabilities of the organization to determine a set of viable solution options, any one of which, if pursued, would help the organization address the business need. These activities provide information that decision makers can use when determining which strategic initiatives to pursue, which activities to perform, and which components of portfolios to implement or terminate. The results provide the contextual information used when initiating portfolio components, programs, or projects and establishing portfolio, program, or project and product scope.

Understanding the business problems and opportunities with stakeholders is important for all programs and projects; the degree to which a Needs Assessment is formally documented depends upon organizational, cultural, environmental, market, and possibly regulatory constraints.

4.1 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY

Identify Problem or Opportunity is the process of identifying the problem to be solved or the opportunity to be pursued. The key benefit of this process is the formation of a clear understanding of the situation that the organization is considering to address. If the problem or opportunity is not thoroughly understood, the organization may pursue a solution that does not address the business need. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 4-2. Figure 4-3 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Part of the work performed within Needs Assessment is to identify the problem being solved or the opportunity that needs to be addressed. To avoid focusing on the solution too soon, emphasis is placed on understanding the current environment and analyzing the information uncovered. Asking questions such as “What problem are we solving?” or “What opportunity might transform how we service our customers?” allows for exploring the situation with stakeholders without jumping directly into a solution.

Various types of elicitation are performed to draw out sufficient information to fully identify the problem or opportunity. Once there is a broad understanding of the situation, it is necessary to elicit relevant information to understand the magnitude of the problem or opportunity. Lack of data can result in proposing solutions that are either too small or too large compared to the problem at hand. This process occurs in conjunction with Section 6.3 on Conduct Elicitation, as much of the information needed to identify the problem or opportunity is obtained through effective elicitation.

Once the problem is understood, a situation statement is drafted by documenting the current problem that needs to be solved or the opportunity to be explored. Drafting a situation statement ensures a solid understanding of the problem or opportunity that the organization plans to address. The situation statement is reviewed and approved with key stakeholders to ensure that the solution team has correctly assessed the situation. If the situation statement is not properly understood, or if the stakeholders have a different idea of the situation, there is a risk that the wrong solution will be identified. The business problem or opportunity is defined in support of portfolio and program management activities and occurs pre-project, as it provides the basis from which a business case will be developed.

4.1.1 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY: INPUTS

4.1.1.1 ASSESSMENT OF BUSINESS VALUE

Described in Section 9.1.3.1. In business analysis, business value refers to the time, money, goods, or intangibles in return for something exchanged. Business analysis involves reviewing implemented or partially implemented solutions to assess whether the business value that the organization expected to provide is being delivered. When there is a significant variance between expected and actual value, Needs Assessment activities are performed to analyze the situation and uncover any resulting problems or opportunities. The assessment of business value, when negative, is used to determine whether a problem exists and to what severity. When the business value exceeds the value that was expected, the situation that is analyzed is considered an opportunity because the organization can pursue it to further enhance the positive results being received. Solution assessment activities need to be performed on an ongoing basis, because, over time, an organization may change its value expectations for a solution.

4.1.1.2 ELICITATION RESULTS (UNCONFIRMED/CONFIRMED)

Described in Sections 6.3.3.1 and 6.4.3.1. Elicitation results consist of the business analysis information obtained from elicitation activities. Results of prior discussions can take many forms, such as sketches, diagrams, models, and notes on flipcharts, sticky notes, or index cards. Past results of prior discussions and elicitation activities may be used as a starting point to learn enough about the situation to adequately understand the context of the problem or the opportunity being investigated. Through analysis and continued collaboration, the elicitation results used to identify the problem or opportunity may transition from unconfirmed to confirmed, demonstrating the iterative nature of elicitation and analysis within business analysis.

4.1.1.3 ENTERPRISE ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS (EEFs)

Described in Sections 2.2.1 and 2.2.2. EEFs are conditions, not under the immediate control of the team, that influence, constrain, or direct the portfolio, program, or project. While performing Needs Assessment activities, including researching an existing problem or opportunity, a variety of EEFs may be reviewed to better understand the situation being investigated. Some examples include:

- Contractual restrictions that can impose relationships with vendors or third-party suppliers that might be factors contributing to an existing problem;

- Legal and governing restrictions, such as federal, state, local, and international laws and industry standards, that can impose constraints or additional requirements;

- Marketplace conditions that may pose issues that impede the chance of success with a current product, such as shifting competitor attitudes or the image of the organization in the marketplace;

- Social and cultural influences that can impact customer buying habits, imposing positive or negative impacts on the products being offered; and

- Stakeholder expectations and risk appetite that may influence the solution options that the business is willing or able to accept.

4.1.2 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

4.1.2.1 BENCHMARKING

Benchmarking is a comparison of an organization's practices, processes, and measurements of results against established standards or against what is achieved by a “best in class” organization within its industry or across industries. The objective is to obtain insights into how successful organizations perform. Benchmarking results can be used to identify areas where organizational performance requires improvement. Benchmarking is not a technique unique to the business analysis profession, but it is one in which business analysis skills are used to analyze the results.

Once a broad understanding of the situation is obtained, it is necessary to gather relevant data to understand the magnitude of a problem or opportunity. The business analyst should attempt to measure the size of a problem or opportunity to help determine an appropriately sized solution. When data cannot be feasibly collected or insufficient information exists within an organization to understand a current state, benchmarking results may be used to provide information. Benchmarking is further discussed in Section 2.4.5.3 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.1.2.2 COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS

Competitive analysis is a technique for obtaining and analyzing information about an organization's external environment. Results of competitive analysis may identify competitor strengths that impose threats or may uncover an area of weakness an organization has in comparison to its competition. These gaps are important to recognize if an organization is to remain competitive. Discoveries may identify gaps where customer needs are not being met or are being completely overlooked, providing an opportunity to develop products to address the void or identify new markets for existing products. Competitive analysis is a component of market analysis. Competitive analysis is further discussed in Section 2.4.5.3 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide. For information on market analysis, see Section 4.1.2.5.

4.1.2.3 DOCUMENT ANALYSIS

Document analysis is an elicitation technique used to analyze existing documentation to identify information relevant to the requirements. While identifying problems or opportunities, this technique involves reviewing information relevant to the business need. For example, strategic goals and objectives, performance goals and results, customer survey results, documentation about current processes, and business rules might be analyzed. The objective is to identify and review the most relevant information to support analysis efforts when determining the problem or opportunity. For more information on document analysis, see Section 6.3.2.3.

4.1.2.4 INTERVIEWS

Interviews are a formal or informal approach to elicit information from individuals or groups of stakeholders by asking questions and documenting the responses provided by the interviewees. Interviews with key stakeholders can produce a wealth of information to support the identification of a problem or opportunity. Follow-up interviews can be performed to discover the finer details of the situation being examined. Interviews are one of several elicitation techniques that can be used to discover information needed to develop the situation statement. For more information on interviews, see Section 6.3.2.6.

4.1.2.5 MARKET ANALYSIS

Market analysis is a technique used to obtain and analyze market characteristics and conditions for the organization's market area and then overlay this information with the organization's plans and projections for growth. Information pertaining to any number of characteristics can be researched—for example, market size, trends, growth rates, customers, products, distribution channels, opportunities, threats, and many others. The information obtained is used by the organization in decision making, specifically to influence decisions regarding investments in future products. Market analysis results can be used to support strategic planning initiatives and provide context for future elicitation.

Analysis results may uncover threats such as shifting consumer preferences, new competitors entering the marketplace, new regulations, or downward trends in buying habits. A thorough market analysis includes information about the industry and market in which an organization operates, competitors, areas of risk and constraints, and projections such as expected sales growth or market share. This information is valuable when analyzing the business for problems or opportunities.

4.1.2.6 PROTOTYPING

Prototyping is a method of obtaining early feedback on requirements by providing a model of the expected solution before building it. When identifying problems or opportunities, this technique is useful to learn and discover what is valuable from the perspective of the customer. Low-fidelity prototyping, using models that provide a visual representation of what may eventually evolve into a product's design, may be particularly valuable for identifying problems and opportunities in projects using an adaptive approach to development. Low-fidelity prototyping may also be useful for any situation in which visual communication is more effective than verbal communication. For more information on prototyping, see Section 6.3.2.8.

4.1.3 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY: OUTPUTS

4.1.3.1 BUSINESS NEED

A business need is the impetus for a change in an organization, based on an existing problem or opportunity. It provides the rationale for why organizational changes are being proposed and why a new portfolio component, program, or project is being considered. Once clearly defined, it is used to provide context when discussing the future state, solution options, and business requirements.

4.1.3.2 SITUATION STATEMENT

In business analysis, a situation statement is an objective statement of a problem or opportunity that includes the statement itself, the situation's effect on the organization, and the resulting impact. The situation statement provides a concise format for presenting the problem or opportunity statement. Organizations may have other preferred formats. The important point is not so much the format but rather to ensure that the team discusses and agrees on the situation prior to discussing solutions. Refer to Section 2.3.4 in Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide for an example of how to document a situation statement.

4.1.4 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Identify Problem or Opportunity are described in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Identify Problem or Opportunity

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Identify Problem or Opportunity | |

| Approach | Performed prior to portfolio, program, or project initiation during an early planning iteration; the degree to which Needs Assessment is formally performed depends upon organizational, cultural, environmental, market, and/or regulatory constraints. | Performed prior to portfolio, program, or project initiation, Needs Assessment is performed as a more formal process where the situation statement is drafted, reviewed, and approved. |

| Deliverables | Adaptive projects often create a brief statement of project intent. In whatever format it takes, the statement of intent typically states the business objectives, value propositions, benefits, goals, milestones, customers and partners, etc., that were identified as part of a strategic planning effort and are part of the project. It may also include very high-level user epics that are later broken down into user stories when the story is selected as a feature of a release. Situations involving higher risk or in regulated industries may require a documented situation statement. |

Documented situation statement. Any models needed to assess the situation. |

4.1.5 IDENTIFY PROBLEM OR OPPORTUNITY: COLLABORATION POINT

All levels of management can serve as sources of information to provide the context and history behind a problem or opportunity. These managers can also remove barriers that stand in the way of gaining access to other key stakeholders who hold needed information. Sometimes the information these managers possess is difficult to obtain because of management availability and scheduling difficulties. When this occurs, business analysts may need to work with proxies who serve as alternates.

4.2 ASSESS CURRENT STATE

Assess Current State is the process of examining the current environment under analysis to understand important factors that are internal or external to the organization, which may be the cause or reason for a problem or opportunity. The key benefit of this process is that it provides a sufficient understanding of the existing state of the organization, providing context for determining which elements of the current state will remain unchanged and which changes are necessary to achieve the future state. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 4-4. Figure 4-5 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Assessing the current state involves researching and analyzing various aspects of the existing organizational environment to understand a situation of concern or interest to the business. The area of analysis may involve a portfolio, program, or project; a department or business unit within the organization; an aspect of the competitive environment; a particular product; or any number of other areas. Various factors can be analyzed, such as the organizational structure, current capabilities, culture, processes, policies, enterprise and business architectures, capacities such as human resources and capital, and external factors. It is common for the information obtained as part of this process to be more detailed than the information analyzed as part of defining the problem or opportunity, since ongoing elicitation activities have continued to cultivate the information. Assess Current State occurs in conjunction with Section 6.3 on Conduct Elicitation.

Evaluating the current capabilities of the organization is a significant focus during a current state assessment. A capability is a function, process, service, or other proficiency of an organization. Capabilities enable an organization to achieve its strategy. The analysis of a problem and its associated root causes allow an organization to identify the capabilities that will be needed or need to be matured to address the business need. Any limiting factors, along with the associated root causes for such factors, are captured and the capabilities or features required to address these duly noted.

Current state assessments are performed to learn enough about the problem or opportunity to adequately understand the situation without the need for conducting a full analysis of requirements. Information about the current state may be obtained through various elicitation methods such as document analysis, interviews, observation, and surveys.

Business analysis activities should be focused on analyzing the areas relevant for defining the situation statement and should be careful not to lead to analysis of areas that are out of scope or not helpful for the eventual definition of the future state. In situations where the current state has recently been assessed in sufficient detail, it is sometimes possible to use that knowledge as the basis for defining the future state without conducting yet another current state assessment. In some organizations, the analytical resources who conduct current state assessments may be a different team of analysts from the analytical resources who perform business analysis on the project if one is approved and initiated.

4.2.1 ASSESS CURRENT STATE: INPUTS

4.2.1.1 ENTERPRISE AND BUSINESS ARCHITECTURES

Described in Section 2.2.2. Enterprise architecture is a collection of business and technology components needed to operate an enterprise. Enterprise architecture is assembled in the form of a schematic or model. Models can be analyzed to understand the strategic and operational impacts that a change will have on various aspects of the enterprise. Business architecture is a subset of the enterprise architecture and contains components such as the business functions, organizational structures, locations, and processes of an organization, including documents and depictions of those elements.

Enterprise and business architectures are a fundamental input into the current state assessment because they visually and holistically depict different aspects of the enterprise and organizational structures that need to be understood for future business analysis work. These architectures provide the most value when they are current, but even outdated models can be leveraged and used as a starting point for conversation with business stakeholders. When architecture models do not exist, business analysis can be performed to begin to develop the aspects of the models most relevant to the situation being analyzed. Aside from architecture models, the actual systems or data supported by the systems can be reviewed from a high level to understand key data components, current relationships, and business rules. This work can be performed using the support of an enterprise or business architect.

4.2.1.2 ORGANIZATIONAL GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Organizational goals define the measurable targets that a business establishes in order to deliver on its strategy. Organizational objectives are the statements aimed at directing the actions of the organization to reach its goals. Goals are typically broad based and span one or more years. Objectives enable goals, are more specific, and tend to be of shorter term, often with durations of 1 year or less. Goals and objectives provide criteria that are used when making decisions regarding which programs or projects are best pursued.

Existing organizational goals and objectives may be reviewed as part of the current state analysis. Organizational goals and objectives are often revealed in internal corporate strategy documents and business plans. These documents and plans may be reviewed to acquire an understanding of the industry and its markets, the competition, products currently available, potential new products, and other factors used in developing organizational strategies. If corporate strategy documents and plans are not available for review, it may be necessary to interview stakeholders to determine this information. Organizational goals and objectives are further discussed in Section 2.4.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.2.1.3 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. The situation statement provides an objective statement about the problem or opportunity the business is looking to address, along with the effect and impact the situation has on the organization. The assessment of the current state is compared against the situation statement to determine the impact of a problem or opportunity on the existing organizational environment.

4.2.2 ASSESS CURRENT STATE: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

4.2.2.1 BUSINESS ARCHITECTURE TECHNIQUES

Business architecture techniques are organizational frameworks available to model business architecture, each providing different approaches for analyzing various aspects of the business. These models can serve as checklists, frameworks, or job aids for assessing the current state and can be used to guide strategy decisions within the organization, specifically at the portfolio and program levels.

4.2.2.2 BUSINESS CAPABILITY ANALYSIS

Business capability analysis is a technique used to analyze performance in terms of processes, people skills, and other resources used by an organization to perform its work. Historical data obtained from analyzing current capabilities are used to understand trends and determine what measures will be helpful guidelines for determining whether a capability is performing as it should be in the current state. The historical data are used to establish performance standards by which current and future performance is evaluated. In the current state, the objective is to determine a specification by which business capabilities can be assessed and performance measured and monitored on an ongoing basis. In the future state, this specification can be used to establish a benchmark for future performance.

4.2.2.3 CAPABILITY FRAMEWORK

A capability framework provides a set of descriptions about the key skills, knowledge, behaviors, abilities, systems, and overall competencies of value to an organization. The capabilities analyzed can be for people or products. Capability frameworks may include information about physical, financial, informational, or intellectual capabilities. Some capabilities are available because of the availability of assets that support them. A physical capability could be the usage of machinery for construction, which requires both the machinery itself and individuals with the capability to operate it, and an intellectual capability could be copyrights and intellectual property. Capabilities for people are typically listed by role or position. This information supports improved decision making with regard to training, hiring, or allocating people resources to processes or projects. Capability frameworks may contain information about the competencies that enable the organization to operate today and may be used as a starting point when performing a gap analysis to identify the capabilities needed to achieve the future state. There are many different formats for presenting capability information; Tables 4-2 and 4-3 show two ideas for people- and product-focused discussions. The rows and columns could be changed or switched in either table. Some organizations refer to these types of frameworks as maturity models.

4.2.2.4 CAPABILITY TABLE

Capability tables are used for analyzing capabilities in a current or future state. Within future-state analysis, the model can be used to display the capabilities needed to solve a problem or seize an opportunity. The technique can be applied to depict the relationship between a situation, its root causes, and the capabilities needed to address the situation. The model can provide an easy way to visualize current problems, the associated root causes, and the proposed new capabilities or features that if pursued, could address the problem. Today, different forms of capability tables exist. Table 4-4 shows a sample format of one possible way to structure a capability table. Capability tables are further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.4.5.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

Table 4-4. Capability Table Sample Format

| Problem/Current Limitations | Root Cause(s) | New Capability/Feature |

| Problem #1 | 1st root cause for problem #1 | • New capability • New capability |

| 2nd root cause for problem #1 | • New capability | |

| 3rd root cause for problem #1 | • New capability | |

| Problem #2 | 1st root cause for problem #2 | • New capability • New capability |

| 2nd root cause for problem #2 | • New capability |

4.2.2.5 ELICITATION TECHNIQUES

Elicitation techniques are used to draw information from various sources. Information about the current state may be obtained through various elicitation methods as described in Section 6.3 on Conduct Elicitation. A few common techniques that are effective during current state analysis are document analysis, interviews, observation, and questionnaires and surveys:

- Document analysis. An elicitation technique used to analyze existing documentation and identify relevant product information. Many documents found within an organization can provide relevant information about the current state, such as training materials, product literature, standard operating procedures, or deliverables from past projects. For more information on document analysis, see Section 6.3.2.3.

- Interviews. A formal or informal approach to elicit information from stakeholders. Interviews can be scheduled with various stakeholders who possess key information about the current state, such as the users of an existing solution or participants in existing processes where problems have been identified. For more information on interviews, see Section 6.3.2.6.

- Observation. An elicitation technique that provides a direct way of eliciting information about how a process is performed or a product is used, by viewing individuals in their own environment performing their jobs or tasks and performing processes. Through observation, the observer can experience the current state firsthand. For more information on observation, see Section 6.3.2.7.

- Questionnaires and surveys. Written sets of questions designed to quickly accumulate information from a large number of respondents. Surveys can be developed to elicit information about the current state—for example, areas where customers or business stakeholders may wish to see improvements or have concerns or existing problems. When confidentiality is made part of the process, participants may be more willing to provide information that they would not otherwise provide in a face-to-face forum like an interview. For more information on questionnaires and surveys, see Section 6.3.2.9.

For more information about elicitation techniques, see Section 6.3.2.

4.2.2.6 GLOSSARY

In business analysis, a glossary provides a list of definitions for terms and acronyms about a product. A glossary should be started as early as possible in portfolio, program, or project analysis to support common language; therefore, it is a technique that is commonly started with needs assessment activities. It may be possible to reuse a common glossary maintained as part of the organization's business architecture or from past project archives. For more information on glossaries, see Section 7.3.2.3.

4.2.2.7 PARETO DIAGRAMS

A Pareto diagram is a histogram that can be used to communicate the results of root cause analysis. Pareto diagrams are a special form of vertical bar chart used to emphasize the most significant factor among a set of data. The vertical axis can depict any category of information that is important to the product team, such as cost or frequency, or consequences such as time or money. The horizontal axis can display the categories of data being measured—for example, types of problems or cause categories. When analyzing problems, the vertical axis might depict the frequency at which different types of problems are occurring, how many times a cause category was identified, or the total cost associated with resolving different product issues. The data results are displayed in descending order, which easily draws attention to the problems, causes, or costs that have the greatest significance and thereby require the most attention. The format of a Pareto diagram helps demonstrate the 80/20 principle whereby 80% of problems can be related back to 20% of the causes. Pareto diagrams are also known as Pareto charts. The process of creating these visuals is called Pareto analysis. Figure 4-6 shows a sample format of a Pareto diagram.

4.2.2.8 PROCESS FLOWS

Process flows describe business processes and the ways stakeholders interact with those processes. Process flows can be used to document current as-is processes of the business. The diagrams provide visual context for discussions with stakeholders and the product team about how the existing environment performs its work. The models can also be used to analyze the ways in which a process contributes to a given problem. Value stream maps—a variation of process flows—can be used to identify process steps that add value (value stream) and those that do not add value (waste). The information can be used to identify areas where a process might be streamlined to eliminate inefficiencies. For more information on process flows, see Section 7.2.2.12.

4.2.2.9 ROOT CAUSE AND OPPORTUNITY ANALYSIS

Once a situation is discovered, documented, and agreed upon, it needs to be analyzed before being acted upon. After the problem to be solved or the opportunity to pursue has been agreed upon, the problem or opportunity can be broken down into either the root causes or opportunity contributors so that a viable and appropriate solution can be recommended. Two techniques commonly used to perform this analysis are the following:

- Root cause analysis. Techniques used to determine the basic underlying reason for a variance, defect, or risk. When applied to business problems, root cause analysis can be used to discover the underlying causes of a problem so that solutions can be devised to reduce or eliminate them.

- Opportunity analysis. Techniques used to study the major facets of a potential opportunity to determine the possible changes in products offered to enable its achievement. Opportunity analysis may require additional work to study the potential markets an organization may consider entering.

Several techniques can be used to analyze root causes and opportunities, including the following:

- Cause-and-effect diagrams:

- Fishbone diagram. A version of a cause-and-effect diagram used to depict a problem and its root causes in a visual manner. These diagrams are snapshots of the current situation and high-level causes of why a problem is occurring. They help trace the undesirable effects of issues back to their root causes. Use of this technique helps the product team avoid jumping to a solution without understanding the true causes of why an issue is occurring.

The fishbone diagram uses a fish image, where the problem (effect) is listed at the head and the causes and subcauses of the problem are placed on the bones of the fish. Causes are grouped into categories and each grouping branches off from the backbone of the fish. Category names are placed in rectangular boxes to easily identify the groupings. The structure of the fish provides a layout to visually assess the relationships between the causes and effects, and helps organize the ideas and connections. The model is often a good starting point when first analyzing root causes to problems; however, the technique will not be sufficient for understanding all root causes. Fishbone diagrams are commonly referred to as cause-and-effect or Ishikawa diagrams. Figure 4-7 shows a sample format for a fishbone diagram. The fishbone diagram is further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.4.4.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

- Interrelationship diagram. A special type of cause-and-effect diagram that depicts related causes and effects for a given situation. Interrelationship diagrams help uncover the most significant causes and effects involved in a situation. They are helpful for visualizing complex problems that have seemingly unwieldy relationships among multiple variables. In some cases, the cause of one problem may be the effect of another. An interrelationship diagram can help stakeholders understand the relationships between causes and effects and can identify which causes are the primary ones producing a problem. Interrelationship diagrams are most useful for identifying relationships among root causes, but like fishbone diagrams, they are not sufficient for understanding all root causes.

Constructing an interrelationship diagram helps participants isolate each dimension of a problem individually without using a strict linear process. Focusing on the individual dimension allows participants to concentrate on and analyze manageable pieces of a situation. When the analysis is complete, the diagram sheds considerable light on the problem, but only after the entire diagram has been assembled. Figure 4-8 shows an interrelationship diagram format. Interrelationship diagrams are further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.4.4.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

- Five-Whys. A technique that suggests anyone trying to understand a problem needs to ask why it is occurring up to five times in order to thoroughly understand the problem's causes. The technique does not advocate having a person literally ask the participant the question “Why?” five times; rather, it promotes ongoing questioning to engage the participant in deeper levels of discussion provoked by more targeted questioning. The facilitator or interviewer discusses a problem and continues to explore why the situation is occurring until the root cause becomes clearer, typically uncovering the root cause after five rounds of questioning. The Five-Whys technique is further discussed in Section 2.4.4.1 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.2.2.10 SWOT ANALYSIS

SWOT analysis is a technique for analyzing the strengths (S) and weaknesses (W) of an organization, project, or option, and the opportunities (O) and threats (T) that exist externally. This technique can be used to assess organizational strategy, goals, and objectives and to facilitate discussions with stakeholders when discussing high-level and important aspects of an organization, especially as they pertain to a specific situation. SWOT is a widely used tool to help understand high-level views surrounding a business need. SWOT can be used to create a structured framework for breaking down a situation into its root causes or contributors.

SWOT investigates the situation internally and externally as follows:

- Internally:

- Shows where the organization has current strengths to help solve a problem or take advantage of an opportunity.

- Reveals or acknowledges weaknesses that need to be alleviated to address a situation.

- Identifies potential opportunities in the external environment to mitigate a problem or seize an opportunity.

- Shows threats in the market or external environment that could impede success in addressing the business need.

Figure 4-9 shows a SWOT diagram format. SWOT diagrams are further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.4.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.2.3 ASSESS CURRENT STATE: OUTPUTS

4.2.3.1 CURRENT STATE ASSESSMENT

The current state assessment is an understanding of the current mode of operations, or the as-is state of the organization. It is a culmination of the analysis results obtained from examination of the existing organizational environment. Typical information captured during the analysis of the current state might be a high-level overview of the existing business context. Examples include models and textual descriptions about existing business processes, key stakeholders, enterprise and business architectures, existing products, and how these items are impacted by the problem or opportunity presented in the situation statement.

A current state assessment may be nothing more than an understanding of the current state and may not necessarily include formalized documentation. Based on the size of the problem, the type and complexity of the project and industry, and various other factors, it may not be necessary to document the results of the current state assessment. If the organization maintains thorough enterprise and business architectures, it may also be sufficient to leverage these organizational process assets in lieu of creating additional as-is documentation for the project.

4.2.4 ASSESS CURRENT STATE: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Assess Current State are described in Table 4-5.

Table 4-5. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Assess Current State

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Not necessarily a formally named process; performed as part of initial planning or iteration 0. | Assess Current State (or as-is analysis) |

| Approach | As-is analysis can be performed throughout the project, as each iteration may focus the as-is discussion on a slice of the overall context. The as-is environment will continue to change, and therefore, will need to be continually assessed to understand how changes in the current state might impact proposed work within the backlog. | As-is analysis is performed up front as a starting point to provide context for future business analysis work. If a recent current state assessment is available, it may be possible to leverage historical information and avoid conducting another current state assessment. |

| Deliverables | Just enough modeling in order to move forward on discussions regarding the future state. The scope of analysis and, hence, the deliverables are focused on the context necessary for the early iterations of development work or to provide context when developing a lightweight business case. | As-is models may be completed to a detailed level. Models constructed may cover the entire problem space up front before requirements elicitation begins. May include models produced in a process modeling tool. The information assembled from the current state assessment may be packaged into a current state assessment document leveraging a standardized template. |

4.2.5 ASSESS CURRENT STATE: COLLABORATION POINT

Business stakeholders contribute deep business knowledge and provide a holistic view of the current state, including historical information that the business analyst needs to start the current state assessment. Relationships with these stakeholders are some of the first ones a business analyst will establish. If a project is initiated, the business stakeholders and business analyst should maintain their collaboration across the entire product development life cycle.

4.3 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE

Determine Future State is the process of determining gaps in existing capabilities and a set of proposed changes necessary to attain a desired future state that addresses the problem or opportunity under analysis. The key benefit of this process is the resulting identification of a set of capabilities required for the organization to be able to transform from the current state to the desired future state and satisfy the business need. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 4-10. Figure 4-11 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Determining the future state involves conducting further elicitation and analysis to define the changes necessary to address the business need to determine which existing capabilities should remain or which new capabilities should be added. In some situations, it may only be necessary to recommend process changes without adding new capabilities or other resources. For more complex situations, like those that span various departments or divisions or involve a highly sophisticated product, the future state may involve adding a combination of new capabilities, including process changes, new machinery, highly skilled staff, physical plants or properties, new training initiatives, new or enhanced IT systems, or a completely redesigned product and determining how to integrate these new elements with existing capabilities.

The future state may involve:

- New work that the organization will take on;

- Outsourcing to acquire capabilities that the organization cannot obtain on its own;

- Applying existing resources in a different manner; or

- Combinations of enhanced, new, or acquired capabilities.

Business analysis is performed to determine which combination of capabilities will best address the stated problem or opportunity. The product team works through discussions using information obtained during the current state analysis about the situation and organizational capabilities. The team develops a clear definition of what the future state will look like, including identification of the capabilities and features required to enable the organization to transform from its current as-is state into this proposed to-be future. The required capabilities and features described here identify what is needed, but do not prescribe a recommended solution. Further analysis is required to evaluate how the capabilities and features will be delivered. Part of this analysis involves obtaining a thorough understanding about how users or customers define value.

Once an understanding about the future state is obtained, business goals and objectives are created to succinctly communicate what the business wants a portfolio, program, or project to deliver. The business goals and objectives here should not be confused with the organizational goals and objectives that were reviewed as part of analyzing the current state. Business goals and objectives align to the organizational goals and objectives, but they are at a lower level because they specify stated targets that the business is seeking to achieve. The term business is used here to represent the area of the organization experiencing the problem or desiring to achieve an opportunity, and represents the area of the organization that has an interest in and willingness to sponsor the need for the change.

4.3.1 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE: INPUTS

4.3.1.1 BUSINESS NEED

Described in Section 4.1.3.1. Business need is the impetus for the change an organization will undertake to address an existing problem or opportunity. The business need guides the business goals and objectives of the future state. It provides the rationale for why the organization desires the change. The business need provides relevant data needed to formulate the desired future state.

4.3.1.2 CURRENT STATE ASSESSMENT

Described in Section 4.2.3.1. Provides the foundational information about the current environment that becomes the starting point from which the future state is based. The current state assessment may include information regarding different aspects about the current environment that can be referenced when determining which changes will be necessary to address the problem or opportunity. Before recommending new capabilities, a review of the existing capabilities occurs to understand the starting point or baseline from which the product team is working.

4.3.1.3 ENTERPRISE AND BUSINESS ARCHITECTURES

Described in Section 4.2.1.1. Enterprise and business architectures comprise a collection of the business and technology components needed to operate an enterprise. Architecture frameworks provide information about the current state that can be used as a starting point for discussions about the future state. Enterprise and business architectures support the product team in understanding which capabilities are present today and help the team draw conclusions about which new or enhanced capabilities will be needed in the future state.

4.3.1.4 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. Provides a context for understanding the problem or opportunity that exists today. It is the starting point from which the future state can be built. The future state is designed to solve or address the problem/opportunity the organization is addressing.

4.3.2 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

4.3.2.1 AFFINITY DIAGRAM

As future state discussions begin, various capabilities might be proposed for addressing the problem or opportunity under analysis. Future state considerations begin at a broad level. Through ongoing exploration and communication, the product team sifts through different ideas and alternatives. These might be discovered through brainstorming, a companion technique to the affinity diagram. Brainstorming is described in Section 5.1.2.1.

Affinity diagrams display categories and subcategories of ideas that cluster or have an affinity to one another. When defining future state considerations, affinity diagrams are used to process a large set of information or ideas into a manageable set of data organized by categories. For problem solving, affinity diagrams help organize related causes of a problem or opportunity. The ability to group data by a common theme allows insights to be identified that might not be possible to uncover when considering the information separately. Figure 4-12 shows a sample format of an affinity diagram. Affinity diagrams are further discussed and an example is provided in Section 2.4.5.2 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.3.2.2 BENCHMARKING

Benchmarking is a comparison technique used to compare one set of practices, processes, and measurements of results against another. During future state analysis, this technique provides another way to determine new capabilities by conducting a comparison against benchmarking studies of external organizations that have solved similar problems or seized opportunities that the organization is considering pursuing. Benchmarking studies often guide final recommendations to address the situation as well as highlight which recommendations not to pursue. For more information on benchmarking, see Section 4.1.2.1.

4.3.2.3 CAPABILITY TABLE

Capability tables relate the identified problems within the current state to their associated root causes and the capabilities required to address the problem in the future state. This technique is a good choice for a model to relate the information obtained during the current state analysis with the information resulting from the future state discussions. The model depicts aspects of the current state alongside the features or capabilities required to address the problem and achieve the future state. For more information on capability tables, see Section 4.2.2.4.

4.3.2.4 ELICITATION TECHNIQUES

Elicitation techniques are used to draw information from different sources. Information about the future state may be obtained through various elicitation methods, as described in Section 6.3 on Conduct Elicitation. A few common techniques that are effective during future state analysis include brainstorming and facilitated workshops:

- Brainstorming. Used to identify a list of ideas within a short period of time. During future state analysis, the product team conducts conversations about potential capabilities that the organization might consider for addressing the situation. Brainstorming is a viable technique to help product teams create an initial list of capabilities. A companion technique is the affinity diagram described in Section 4.3.2.1. For more information on brainstorming, see Section 5.1.2.1.

- Facilitated workshops. Structured meetings led by a skilled, neutral facilitator and a carefully selected group of stakeholders to collaborate and work toward a stated objective. Because facilitated workshops support interactivity, collaboration, and improved communications among participants, the technique is a viable elicitation technique for a team to use when defining the future state. For more information on facilitated workshops, see Section 6.3.2.4.

For more information about elicitation techniques, see Section 6.3.2.

4.3.2.5 FEATURE MODEL

Feature models provide a visual representation of all the features of a solution arranged in a tree or hierarchical structure. The strength of the model is its ability to help visually and logically group feature sets. The model can be utilized to parse out groups of features or capabilities to help facilitate discussions about different future state options that the organization may wish to consider. Different versions of a feature model can be created, with each representing a possible future state alternative. For more information on feature models, see Section 7.2.2.8.

4.3.2.6 GAP ANALYSIS

Gap analysis is a technique for comparing two entities, usually the as-is and to-be state of a business. During Needs Assessment, gap analysis is performed by examining the differences between the current and future states. The current state assessment includes a thorough exploration of elements in the existing environment—for example, processes, systems, staff, and a variety of environmental factors necessary to understand how the organization operates today. The future state assessment includes an exploration of the capabilities required to address the problem or opportunity. Gap analysis is performed by comparing the required capabilities against the existing capabilities and identifying the difference, or “gap.” This gap refers to the missing capabilities that the organization needs to acquire to address the business need in the future state. Gap analysis is further discussed in Section 2.4.7 of Business Analysis for Practitioners: A Practice Guide.

4.3.2.7 KANO ANALYSIS

Kano analysis is a technique used to model and analyze product features by considering the features from the viewpoint of the customer. Kano analysis can be used to help a product team understand the level of importance of features being considered for the future state. During Kano analysis, product features are grouped into one of five categories and plotted on a grid. The vertical axis is used to measure the degree of customer satisfaction that the feature will provide, and the horizontal axis shows how well the product is expected to satisfy or deliver the feature. When placing product features into the Kano categories, the grouping is determined by considering the customer's viewpoint or perception of the feature. This categorization helps the product team understand how each feature is expected to contribute to the customer's satisfaction level. A Kano survey is used to collect the data necessary to plot on the grid. The discoveries made during Kano analysis provide good information that the team can consider when prioritizing customer needs. A Kano model can also be used to analyze products.

There are five product feature categories commonly used in a Kano model. Some organizations elect to use only the first three. A description of each is as follows:

- Basic. Features that provide little satisfaction to stakeholders, but, when missing from the end solution, cause extreme dissatisfaction. Stakeholders do not give a lot of thought to the features in this category because it is assumed that the final solution will include them.

- Performance. Features that stakeholders think about, desire, and use to consciously evaluate the final solution. These features can either satisfy or dissatisfy the stakeholder, depending on how well the solution addresses them.

- Delighters. Features that differentiate the product from competitors' products and are sometimes referred to as the “wow” factor. Delighters play off of emotion. When these features are present, they provide extreme satisfaction to the stakeholder. When they are not present, typically stakeholders are not even aware that the feature is possible and the stakeholder is not consciously dissatisfied.

- Indifferent. Features that neither satisfy nor dissatisfy a customer. The customer does not care whether these features are included or not. These features plot along the horizontal axis of the Kano model.

- Reverse. Features that decrease a stakeholder's satisfaction level when present and increase it when excluded from the final product.

Customer perceptions can change over time. A competitor may add a similar “wow” factor to their products or improve upon a “wow” factor, which in turn will decrease the uniqueness of the original product; features that once were delighters turn into performance features, or even basic features, as customer expectations evolve.

Figure 4-13 shows a sample format of a Kano model.

4.3.2.8 PROCESS FLOWS

Process flows are used to depict the business processes in the current state and used as a starting point for discussions concerning the changes desired and required for the future state. Process flow modeling is a good technique for performing what-if analysis to walk through various future state scenarios with key stakeholders. The diagrams and flows produced during process flow modeling can be modified to reflect and analyze various future states to support decision making. Various simulation packages exist where process flows are automated and proposed changes simulated to analyze various elements of the future state before solution options are developed and projects are initiated to implement the changes. For more information on process flows, see Section 7.2.2.12.

4.3.2.9 PURPOSE ALIGNMENT MODEL

The purpose alignment model is a technique that provides a framework to support strategic or product decision making. The framework is used to categorize options by aligning them with the business purpose they support. The model can become a basis for forming decisions about which options to pursue and how to pursue them.

The model helps a product team link business strategy to product strategy. For example, it can be used to work through features in a product backlog to determine the value a feature holds for the organization or a release. For future state analysis, understanding the alignment of product options with business purposes helps the product team consider different solution options and which features to address and when. For more information on product backlogs, see Section 7.3.2.4.

While this technique is typically used as a basis for making strategic or high-level product decisions, some organizations also use it to analyze and facilitate discussions about product requirements and features, including the value each provides. These discussions, in turn, can become an input into prioritization activities. The remainder of this section focuses on using a purpose alignment model to categorize product features.

At the project level, product features are placed on a quadrant matrix considering two factors: criticality and market differentiation. A product feature that is determined to be highly critical may be needed for the organization to stay in business or meet regulations. A product feature rated as a market differentiator may contribute to the organization's ability to gain market share, increase sales, or surpass competitor offerings. The discussions a product team works through when determining how best to position the feature on the grid promotes a shared understanding about value. The analysis provides information to help determine which features the organization should invest in. The four categories of purposes in the model and the actions that might be taken from a feature perspective are as follows:

- Differentiating. Features in this category are mission critical and provide high market differentiation. They can help the organization gain market share, improve its competitive advantage, and outrival its competitors. Organizations need to continually invest in this area to excel, provide uniqueness, and stay ahead of the competition. When they do, customers will consider the organization to be an innovator.

- Parity. Features here help the organization maintain its parity in the marketplace. Investments in parity features may be mission critical, but they do not provide the organization with a competitive advantage. Features in this category simply ensure that the business stays on par with competitor offerings.

- Partner. Features assigned here are not considered mission critical, but if provided, they would enable the organization to differentiate itself in the market. As a result, an organization will look externally for a partner company to provide these features but will not invest in these features itself. A viable partner would be an organization that today is differentiated by offering these features.

- Who cares. Features in this category are neither differentiating nor mission critical to the organization. Features that end up in this category are generally not built.

Figure 4-14 shows a sample format of a purpose alignment model.

4.3.2.10 SOLUTION CAPABILITY MATRIX

A solution capability matrix is a model that provides a simple visual way to examine capabilities and solution components in one view, identifying where capabilities will be addressed in the new solution. When timing information is added, the product team can use the model during planning discussions to understand when different solution components are expected to be delivered.

The matrix can be presented with capabilities listed down the left column and the components of the solution across the top. An X placed at the point of intersection between column and row indicates when the capability is covered by a component of the solution. Product teams can utilize a solution capability matrix to understand which capabilities are covered in the solution or a solution component. The Xs may be replaced with a version number or an iteration number if the team wishes to communicate when a capability will be addressed in the solution. Today, different forms of solution capability matrices exist. Table 4-6 shows a sample format for one possible way of structuring a solution capability matrix.

4.3.3 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE: OUTPUTS

4.3.3.1 BUSINESS GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Business goals and objectives identify what the business expects the portfolio, program, or project to deliver. Business goals and objectives align to the organizational goals and objectives, but are at a lower level because they specify stated targets that the business is seeking to achieve.

4.3.3.2 REQUIRED CAPABILITIES AND FEATURES

The required capabilities and features identify the list of net changes the organization needs to obtain in order to achieve the desired future state. The capabilities and features listed do not prescribe a solution. Additional analysis is still needed to determine how these capabilities and features will be delivered.

4.3.4 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE: TAILORING CONSIDERATIONS

Adaptive and predictive tailoring considerations for Determine Future State are described in Table 4-7.

Table 4-7. Adaptive and Predictive Tailoring for Determine Future State

| Aspects to Be Tailored | Typical Adaptive Considerations | Typical Predictive Considerations |

| Name | Not a formally named process and performed as part of backlog refinement, business modeling, initial planning, or iteration 0. | Determine Future State |

| Approach | Teams explore the future state in slices and discuss it in terms of themes, goals, and objectives. Some organizations may take a broader or organizational viewpoint to this work. Typically, some high-level information on the future state is formed at either project initiation or as part of iteration 0, but that information is constantly evolving as new information emerges. Future state information is reviewed prior to each iteration to ensure that the capabilities required for the future state are known and understood. | To-be analysis is performed up front prior to initiating a project to understand the business goals and objectives. Results from gap analysis are understood to define required capabilities. The to-be state is fully defined and understood before moving forward on proposing viable solution approaches. The future state definition is formally documented, reviewed, and approved with the business. |

| Deliverables | The future state definition may be represented in lightweight documentation. Models utilized to facilitate discussions involve a low level of formality and are often developed on whiteboards or flipcharts. The future state definition is captured and made available to the team on an ongoing basis. Other deliverables may include roadmaps, story maps, and product backlog. | A future state definition can be documented within a tool or within a formal document such as a business case. Models built to assist in defining the future state are often formalized, created with a modeling tool, and archived for future reference. |

4.3.5 DETERMINE FUTURE STATE: COLLABORATION POINT

In some organizations, the analytical resources involved in needs assessment activities may be a different team of analysts from the analytical resources who perform business analysis on the project if one is approved and initiated. Business analysts will often find themselves collaborating with peers who report into different organizational structures or who are supporting other programs and projects.

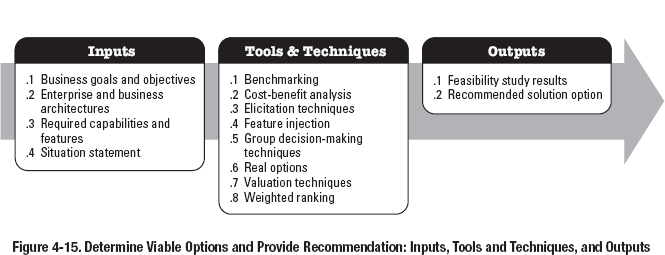

4.4 DETERMINE VIABLE OPTIONS AND PROVIDE RECOMMENDATION

Determine Viable Options and Provide Recommendation is the process of applying various analysis techniques to examine possible solutions for meeting the business goals and objectives and to determine which of the options is considered the best possible one for the organization to pursue. The key benefits of this process are that it validates the feasibility of proposed solutions and promotes the best course of action for executives and decision makers to meet the business goals and objectives. The inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of the process are depicted in Figure 4-15. Figure 4-16 depicts the data flow diagram for the process.

Determining viable options entails conducting discussions with stakeholders and product team members and performing further analysis to define a list of possible solution recommendations to address the business need. The product team considers the information from the current and future state analysis when formulating these options. The product team also determines the solution approach for each option. The solution approach is a high-level definition about the considerations and steps necessary to deliver the solution and thereby transition the business from the current to the future state.

Stakeholders often propose solutions without fully understanding the context around the situation. Presenting the results of needs analysis to key decision makers, including the rationalization why the viable options are being chosen, can reduce the likelihood that an unfit solution will be chosen.

Determining viable options and providing a recommendation entails the following activities:

- Identifying viable options. Using the results of the current and future state analysis to determine which solution options are best for the business to consider.

- Conducting feasibility analysis. Evaluating different factors to determine the feasibility of the options under consideration. Organizations may dictate that the results of the feasibility analysis be captured in a formal document using an approved template, but the level of formality followed depends on organizational standards. Common elements analyzed for each of the options under consideration include the following:

- Constraints. Any limitations that restrict the option under consideration. For more information on constraints, see Section 7.8.

- Assumptions. Any factors that are unknown and are assumed to be true, real, or certain for each option without actual proof or demonstration. For more information on assumptions, see Section 7.8.

- Product risks. Uncertain events or conditions that may have a positive or negative effect on the successful delivery of the solution. For more information on product risks, see Section 7.8.

- Dependencies. Any relationships upon which a solution depends for successful implementation. Dependencies introduce a level of risk; therefore, a solution option with several dependencies may be deemed riskier and determined to be less viable than an option with no dependencies. For more information on dependencies, see Section 7.8.

- Culture. An enterprise environmental factor that can impact both the success of the business analysis effort and the portfolio, program, or project. A lack of acceptance across the organization could potentially limit both the success and expected value of the final solution.

- Operational feasibility. The receptivity of the organization to the change and whether the change can be sustained after it is implemented.

- Technology feasibility. Refers to whether the necessary technology and technical skills exist or can be affordably obtained to adopt and support the solution option. It also includes whether the proposed change is compatible with other parts of the technical infrastructure.

- Supportability. A category of nonfunctional requirements used to evaluate the cost, level of effort, and ease with which each option can be maintained and managed by the organization over time.

- Cost-effectiveness feasibility. An initial, high-level estimate of costs and value of the benefits that the option is expected to deliver. During feasibility analysis, this estimate is not intended to be a complete cost-benefit analysis.

- Time feasibility. The assessment of whether the solution option can be delivered within the time constraints specified. Time constraints may be imposed by the organization, business, or external factors.

- Value. The business value that the solution option will provide to the organization. It includes a discussion of how value may change over time.

- Validation. Provides the assurance that the solution will meet the needs of the customer and other identified stakeholders. Each option will require a different approach and level of effort to validate its alignment to the business objectives. Some options may prove more difficult or costly to validate, which may be of significant interest to the organization when assessing the overall viability of an option.

Constraints, assumptions, product risks, and dependencies are analyzed as part of Section 7.8.

The feasibility analysis should provide sufficient information to compare the list of possible or viable options, and may result in the elimination of some options that are then considered infeasible. Typically, there is not just one factor, such as cost or time, that will determine whether an option is feasible, so the determination of feasibility is best analyzed when several of the factors mentioned above are considered.

- Defining preliminary product scope. Determining the high-level scope defined in terms of the capabilities that each option will provide. At this stage, what is known about the product scope remains at a high level.

- Defining high-level transition requirements. Identifying high-level transition considerations, such as data conversion or training requirements required to transition the organization to the specified solution. Attention should be given to draw out the significant differences in transition needs between each option.

- Recommending the most viable option. A recommendation put forth to identify the option considered the most viable, assuming that more than one option remains viable after the feasibility analysis is completed. The option that is selected is identified, along with the rationale explaining why that selection was made over the other options.

If only one option is judged to be feasible after the analysis is completed, that option, in most cases, will be recommended. When there are no viable options to address the business need, one option is to recommend that nothing be done. When faced with two or more feasible options, the remaining choices can be arranged in rank order, based on how well each one meets the business need. A technique such as weighted ranking is a good choice to perform this analysis.

4.4.1 DETERMINE VIABLE OPTIONS AND PROVIDE RECOMMENDATION: INPUTS

4.4.1.1 BUSINESS GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Described in Section 4.3.3.1. Business goals and objectives identify what the business is expecting the portfolio, program, or project to deliver. Each of the viable options under consideration will be assessed to determine how well it satisfies the stated business goals and objectives. Each option will satisfy the goals and objectives differently, and some options will satisfy them far better than others under consideration.

4.4.1.2 ENTERPRISE AND BUSINESS ARCHITECTURES

Described in Section 4.2.1.1. Enterprise and business architectures provide insights into the current state of the organization. When presenting viable options, each option can be analyzed and explained within the context of existing architectures. Doing this helps frame up the size and complexity of each option in terms that decision makers can more easily relate to and understand.

4.4.1.3 REQUIRED CAPABILITIES AND FEATURES

Described in Section 4.3.3.2. The required capabilities and features identify the list of net changes the organization is looking to obtain in order to achieve the desired future state. Each proposed option will address the capabilities and features differently. Which capabilities and features are covered determines the product scope for each option. Initially, discussions begin at a high level, but as options are formulated, discussed, and further refined, some capabilities may be determined to be more valuable than others and adjustments made to the solution approaches under consideration.

4.4.1.4 SITUATION STATEMENT

Described in Section 4.1.3.2. The situation statement is an objective statement of a problem or opportunity that includes the statement itself, the situation's effect on the organization, and the resulting impact. The situation statement provides context for discussions when identifying a list of viable options.

4.4.2 DETERMINE VIABLE OPTIONS AND PROVIDE RECOMMENDATION: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

4.4.2.1 BENCHMARKING

Benchmarking is a comparison of an organization's practices, processes, and measurements of results against established standards or against what is achieved by a “best in class” organization within its industry or across industries. Benchmarking results can help stimulate ideas for formulating a list of viable options. For more information on benchmarking, see Section 4.1.2.1.

4.4.2.2 COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

Cost-benefit analysis is a financial analysis tool used to compare the benefits provided by a portfolio component, program, or project against its costs. It is commonly used to identify the most viable option from a set of options. Cost-benefit analysis is often conducted prior to project initiation, as part of portfolio or program management activities. Completing a cost-benefit analysis requires an understanding of financial analysis, so business analysis resources may often seek out the support of a financial analyst within their organization to assist with this work. The results of the cost-benefit analysis are included in the business case to demonstrate why the solution option selected and proposed is considered the most viable choice. Organizations often have standards that dictate when and how to perform a cost-benefit analysis, including which financial valuation methods to employ. To perform a cost-benefit analysis, at least one valuation technique is applied to make the financial assessment. Valuation techniques are defined in Section 4.4.2.7.

4.4.2.3 ELICITATION TECHNIQUES

Elicitation techniques are used to draw information from different sources. The information required to formulate a list of viable options is obtained by applying various elicitation techniques, as described in Section 6.3. For example, prototyping can be used to determine whether an option is viable by developing a prototype model to assess stakeholder expectations against the model. Prototypes help eliminate uncertainties about options, thereby reducing product-related risks. For more information on prototyping, see Section 6.3.2.8. For more information about elicitation techniques, see Section 6.3.2.

4.4.2.4 FEATURE INJECTION

Feature injection is a framework and set of principles used to deliver successful outcomes by improving and expediting how a product team develops and analyzes product requirements. The framework is popular with teams that use adaptive development methods. The idea is to focus discussions and analysis on the features where there can be an immediate return of value. In predictive life cycle methods, stakeholders provide a vast amount of information up front, teams analyze the collective set of information, and a set of product requirements is developed from the entire collection of information. Feature injection challenges this traditional approach by guiding the team to analyze only those features that are deemed to be of the highest value. The objective is to reduce the amount of time that teams spend analyzing low-value requirements. Using feature injection, product teams work backwards, focusing on value first and then on features to attain the value. Feature injection follows a three-step approach:

- Step 1: Determine the business value. The team discusses the expected or required value that the business seeks to achieve (the outcome). A technique like the purpose alignment model may help guide these discussions, but other value models can be used as well. When the team reaches a common understanding about expected value, it moves on to Step 2.