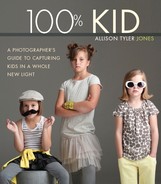

5. The Five M’s of Studio Lighting

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/9, 70–200mm lens

Before you can think out of the box, you have to start with a box.

—Twyla Tharp

Every photographic endeavor starts with a vision—a glimmer of what you want the end result to be. Then begins the selection process of lighting tools and techniques to bring that vision to life. Ironically, the very process of learning to use new tools and techniques can cloud your creative vision for a time until the skills become second nature.

When learning something new, I try to break the basic skills into bite-sized chunks that I can get my mind around quickly. In this chapter I outline the five steps I use to apply lighting theory in my work. I’ve reduced five basic lighting concepts—mood, main, modify, measure, and move—into a decision-making process; it’s a process that I use every time I shoot.

Mood

Before you set up any lights, first decide how you want the image to feel. In other words, establish the mood of the image you want to create. Do you envision a light and airy feel, a dark and dramatic mood, or something in between? Your approach for photographing a sweet, newborn baby might be different from how you would envision a portrait of a moody preteen. What mood do you want to bring to the portrait of this specific child? A good place to begin is with the key of light.

The Key of Light

The key a piece of music is composed in affects the overall tone and feel of the work; photography is no different. The key of lighting you select affects the overall tone and feel of the final image. When lighting an image, there are three basic keys of light that you can use to help convey mood in an image: high-key, mid-key, and low-key lighting. All the keys of light are intended to draw attention to your subject, but they do so in different ways.

High-key lighting

Light, bright, and energetic are words that describe the mood of a high-key portrait. High-key lighting, commonly used in advertising, is simple and clean, and highlights the subject with no distractions. My favorite high-key setup is a white, featureless background that is 1½ stops brighter than the light on the subject.

A high-key lighting setup typically uses three lights: one to light the subject and two (or more) to light the background. The high-key setup is versatile but can be tricky to get right, so I’ve devoted Chapter 7 to it.

I choose high-key lighting when I want to convey energy and motion, as shown in FIGURE 5.1. This setup creates a large area of light for kids to move around in, making it a good choice for capturing girls twirling in their dresses or boys showing off their karate moves. High-key lighting draws attention to the pose and shape of the subject, as in FIGURE 5.2.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/9, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.1 A high-key lighting setup provides a large area of light that allows plenty of room for kids to get their groove on and still be properly lit.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.2 The clean, simple nature of a high-key lighting setup draws the eye to the subject and emphasizes the pose and shape of your subject.

Mid-key lighting

The mid-key portrait is made up primarily of midtones; the only area of strong contrast is created by the light falling on the subject, which draws the viewer’s attention. More subtle and nuanced than high- or low-key lighting, a mid-key portrait can get boring in a hurry unless you carefully create depth and dimension with the light falling directly on your subject. My mid-key lighting setup consists of a single light source on the subject and sometimes a fill reflector opposite the main light (more on this later in this chapter).

Note

High-key lighting is also a good choice when you plan to use the final images in a custom album or card design, because a white background is perfect for use with graphic type treatments. It’s also easy to expand that white background in Photoshop if you want to change how the image is cropped.

Neither light nor dark, a plain, gray background gives a modern, almost commercial feel to a mid-key portrait. The gray background can be achieved by using a roll of gray seamless paper or by simply not lighting a white seamless background portrait, as in FIGURE 5.3.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.3 This mid-key gray background was created by simply not lighting the white wall behind the girl.

I love the look of mid-key lighting when I’m photographing in color, especially with naked babies. With this combination the image appears almost monochromatic, so the only color is the baby’s skin tone, hair, and eye color (FIGURE 5.4).

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.4 The neutral look of mid-key lighting highlights the subject’s skin tone, eye, and hair color.

Low-key lighting

“Moody” describes the feel of a low-key portrait. Composed of predominantly dark tones, the subject of a low-key portrait draws the viewer’s attention, as shown in the photo in FIGURE 5.5 by the appearance of two sisters emerging from shadow into the light.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.5 In this low-key lighting setup, these sisters seem to be emerging into the light from a darkened background.

This classic style references the techniques of old master painters, like Rembrandt and Vermeer, who painted their subjects in darkened environments by the light of a single window. The light on the subject is dramatic and dimensional, with little or no light on the background.

Low-key lighting has a classic, fine art feel to it and is the most emotional and dramatic of the three keys of light. Because it has a heavenly ray-of-light look to it, I use low-key lighting when I want to show off the texture of a child’s skin and focus on every eyelash, as shown in the close-up of the baby in FIGURE 5.6. For low-key lighting, I typically use one light, tightly controlled, to light my subject. There’s nothing like a low-key portrait in black and white. With no color to distract the eye, you see only line, shape, and texture.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/2.8, 60 mm Macro lens

FIGURE 5.6 A low-key setup is perfect for isolating features like eyelashes or skin texture.

Main

Once you’ve decided on the mood you want to convey, it’s time to create a lighting scheme to communicate that mood. Creating a lighting scheme is a process of addition: You start with a main light and then add in more as needed. Studio portrait photographers have a language all their own that refers to the various lights they use to create a lighting scheme. Even if you only ever use one light, it’s helpful to know what all the lights are called and what they are expected to do.

Main or Key Light

Also referred to as a key light, the main light is the primary source of illumination on your subject. The main light is usually the brightest light and determines the overall mood of the scene. It is also responsible for the look of the shadows falling on your subject, as in FIGURE 5.7.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.7 The subject is lit by a main light only and an Octabank is camera left.

Fill Light

A fill light (or a reflector used as fill) is added to a scene to lift or “fill” the shadows created by the main light (FIGURE 5.8). I prefer using a white reflector versus an actual fill light if I use any fill at all. Nothing kills drama in an image more than badly applied fill light, so use it sparingly.

Accent or Kicker Light

A kicker light is pointed at the subject either from the side or from a rear angle, giving definition to the subject and providing separation from the background. I rarely use kicker lights when photographing kids because they require the subject to be glued to a specific spot, and I like to let kids move. I might use a kicker light when photographing a family, where there is less movement going on, or for a particularly cooperative child, as in FIGURE 5.9.

FIGURE 5.9 The subject is lit by a main light, and a reflector fill and kicker light are camera right behind the subject. Notice how the kicker light also acts as a hair light.

Background Light

A background light is used to illuminate all or part of the background to provide separation of the subject from the background, as shown in FIGURE 5.10. I rarely use a background light unless I’m shooting a high-key setup. Then I use two lights to create a completely white background (more on this in Chapter 7).

FIGURE 5.10 The subject is lit by a main light, a reflector fill, a kicker, and one background light.

Hair Light

A hair light is an overhead light that illuminates the subject’s hair and provides separation from the background. I confess that I never use hair lights. A kicker light can double as a hair light (as in Figure 5.9) if I’m photographing a brunette child on a dark background. However, I just don’t like the look of adding in another light for hair. For me, the extra light starts to add too many accents and takes the eye away from the expression.

Less Is More

When it comes to photographing kids, using more than one or two lights to light my subject is too much. The image starts to look overlit, and the emphasis is taken away from the subject. Using accent lights also requires the exact placement of a child (i.e., the child has to be still), and that doesn’t usually happen in my world. My preference is to use lighting setups that allow kids to move a little and that give me the maximum possible margin of error. Most of the time that means using one light and a reflector to light my subject.

Modify

The third M refers to modifying the bare light source to achieve flattering, dimensional light on your subject.

When you’re first learning to use lighting in your work, it’s easy to get hung up on the quantity of light—how bright or dark your image is. As you learn to properly nail your exposure, you’ll understand that it’s actually the quality of light that will make or break the image. Ironically, the easiest way to see the quality of the light is to pay attention to the shadows.

From your experience shooting in natural light, you know that if you shoot in harsh, direct sunlight, the result will be harsh, hard-lined shadows on your subject. If you move your subject to a setting with open shade or light that is diffused in some way, you’ll see a softer gradation from light to shadow on your subject’s face. Studio lighting is no different. Harsh, direct light created by a bare flash bulb, as in FIGURE 5.11, creates harsh, hard-lined shadows. Placing a modifier between the light and your subject, like the Octabank in FIGURE 5.12, will change those shadows from hard to soft. The point at which the light on your subject changes from light to shadow is called shadow transfer. Placing something between the light source and your subject modifies the light and changes how the shadow transfer appears—in this case from hard to soft.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.11 A monolight used as a bare-bulb, direct light source creates cut-out shadows behind the subject.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.12 An Octabank modifier is placed on the monolight to diffuse the light on the subject. Notice how the shadows are either filled in or considerably softened by diffusing the light.

Light modifiers are to your lights as lenses are to your camera. Like lenses, light modifiers dramatically affect how the final image looks. Because modifiers come between the light and your subject, they directly affect the quality of the light falling on your subject. Some modifiers diffuse the light, whereas others increase contrast and concentrate the light. You use modifiers to shape and control the light in distinct ways—for example, by diffusing, reflecting, concentrating, or subtracting light from your subject.

Diffusers

As mentioned earlier, diffusers (e.g., an Octabank) soften light and can also enlarge the source by diffusing light over a larger area. Shooting with a strobe bulb that is 3 inches across into a 60-inch Octabank dramatically diffuses and enlarges the light source, and as you’ll soon learn, when it comes to flattering light, bigger is better. The most commonly used lighting diffusers in portraiture are umbrellas, softboxes, and Octabanks.

Ironically, the easiest way to see the quality of the light is to pay attention to the shadows.

Umbrellas

Umbrellas are the least expensive light modifiers on the market. They are available in black with white, silver, or gold interiors. It’s best to start with the convertible umbrella with a white interior. Use the convertible umbrella in reflective mode by shooting your flash into the umbrella, and the light will reflect onto your subject. Or, use it in shoot-through mode by removing the black fabric and shooting the flash through the umbrella toward your subject. In reflective mode, the light is more contrasty and specular. In shoot-through mode the light source becomes much larger and more diffused, but it can also be harder to control because a big, shoot-through umbrella scatters lots of light everywhere.

Softboxes

Softboxes, aka light banks, are collapsible fabric boxes manufactured to direct and diffuse light. Softboxes are black on the outside and have a front diffusion panel to diffuse the light. They come in all shapes and sizes from very small to enormous enough to light a car. A large softbox acts like a big, gorgeous window of light. Softboxes with recessed diffusion panels allow you to control the light spill better than softboxes with diffusion panels that are flush with the front of the box. A 4 x 6-foot softbox is big enough to produce the look of a very large window of soft light (FIGURE 5.13). A smaller softbox allows you concentrate soft light in a smaller area.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.13 The soft, dimensional light in this image was created by a light diffused with a 4 x 6-foot softbox to one side of the subjects.

Octabanks

All photographers have a favorite modifier that they wouldn’t be without, and for me that is my 60-inch Octabank. Octabanks are shallower than softboxes, allowing you to feather the light more easily across one or more subjects and sometimes eliminate the need for a fill light or reflector (more about feathering light in Chapter 6). Because they are not as deep and directional as softboxes, Octabanks create a huge, forgiving wall or ceiling of light. This makes lighting wiggly kids easier because it gives them more room to roam and still be in good light. When I’m photographing more than four kids or kids with their family, I’ll bust out the 7-foot Octabank to create an even larger light source, as shown in FIGURE 5.14.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.14 Using a large diffuser, like a 7-foot Octabank camera right, made it easy to get good light on five very wiggly kids.

Strip banks

Strip banks are softboxes that are twice as long as they are wide. They are used for accent lighting (e.g., as a kicker light or even a hair light for a group of people). Long and skinny, strip banks can provide head to toe rim lighting (light that highlights the edges of a subject) for a child, which can help separate the child from the background.

Photek Softlighter

If you’ve seen any of the YouTube behind-the-scenes videos of Annie Leibovitz’s photo shoots, you’ve seen the Photek Softlighter modifier in action. Part umbrella, part softbox, and part Octabank, the Photek 60-inch Softlighter is the perfect all-in-one modifier, especially if you’re just starting out. It is relatively cheap (around $100) and creates gorgeous light. The Softlighter can be used as a reflective or shoot-through umbrella, and with the diffuser sock attached to the front, it acts as a 60-inch Octabank. The shaft on the umbrella is removable, which allows you to position the light very close to your subject without the shaft appearing in the photo. I take the Photek Softlighter with me on every location shoot; it’s like a portable Octabank. If it’s good enough for Annie, it’s good enough for me.

Reflectors

You’ve probably used reflectors in your natural-light work when you needed to open up the shadows or reflect sunlight onto the shadow side of your subject. In the studio, reflectors are most commonly used opposite a main light to keep the shadow areas in an image from becoming too dark. In this way they can act as a fill light. However, I’d rather use a reflector than a fill light because reflectors are easier to control and faster to set up than an additional light.

V-flats

I love the look of a single light source, but sometimes you need a little reflection to act as a fill light. My hands-down, favorite reflector to use in the studio is the white side of a V-flat. V-flats are made by bookending two pieces of Z-board with gaffer tape (see the sidebar “The Beauty of V-flats,” later in this chapter). Z-board comes in 4 x 8-foot sheets, which are white on one side and black on the other. The board has a plastic finish to it with a foam center and is about 3/16 inch thick.

When I suspect the shadows are too dark and may need some fill, as in FIGURE 5.15, I’ll pop in a V-flat as a reflector by positioning it opposite my main light to catch some of that light and throw it back onto the shadow side of my subjects.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.15 I was going for a dark and moody look in this image but thought the shadows might be a bit too dark.

If the reflector is filling in my shadows too much, as in FIGURE 5.16, I’ll back it farther away or remove it altogether. The dull, white side of a V-flat provides just the right amount of reflection, so I rarely use reflectors with a metallic finish (such as silver) because the light is too specular for my taste.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.16 Adding a V-flat opposite the main light added too much fill, and I lost the drama I was originally looking for.

I’d rather use a reflector than a fill light because reflectors are easier to control and faster to set up.

V-flats don’t travel well, so when I’m shooting on location, I’ll take my two favorite reflectors with me—the Lastolite TriGrip and the California Sunbounce reflectors.

Lastolite TriGrip reflector

The TriGrip reflectors come in various sizes, but the one I use most is 48 inches, with white on one side and silver on the other. I like the TriGrips because of their sturdy handles, which allow you to use them without needing an assistant.

Note

When you’re investing in studio lights, stick with one brand of lights if you are adding lights over time. The reason is that each brand of lights has its own system of adapters (sometimes called speed rings) to attach the modifiers to your lights. Just like Canon lenses won’t work on Nikon cameras, a Profoto speed ring won’t attach to an AlienBees light. You can buy different adapters for your modifiers, but you’ll save money and prevent headaches later if you plan ahead and stick with one system from the beginning.

California Sunbounce reflector

The California Sunbounce reflector is huge when it’s set up (4 x 6 feet) but great on location when you need to either block the sun or reflect light onto a group of kids. It has a sturdy frame and is easy to attach to a light stand. Although the California Sunbounce reflector can be a pain to set up and break down, when you need a reflector that’s almost the size of a V-flat that can be packed in your car, this is the one to use. The one I use is white on one side and matte silver on the other.

Concentrating the Light

Light modifiers that concentrate light by either restricting or directing the light source are most often used as accent lights, but sometimes they can make for an interesting twist on your main light. These are the, not-necessary-but-nice-to-have kinds of modifiers that you’ll want to explore once you’ve established your foundation of lighting with the aforementioned modifiers.

Beauty Dish

Somewhere out there is a seasoned studio photographer reading this section and rolling his eyes at the mere mention of a Beauty Dish in a book about photographing children. The reason is that Beauty Dishes are notoriously difficult to use, because the placement of the light is critical, and lighting modifiers that require critical placement are not usually the type of modifiers you use when photographing children. So what? There’s something about the quality of light from a Beauty Dish that’s unlike any other modifier on the market. The concentrated light that bathes the face and creates dark (but not too dark) shadows beneath the chin is very appealing, and I love it. It’s not the easiest modifier to work with, but the image in FIGURE 5.18 reminds me that I never regret it when I take chances.

Grid spots

Grid spots are rigid, honeycombed discs that concentrate the light source to varying degrees. Grid spots focus and narrow your light to a tightly controlled beam that you can place wherever you want. I have a set of 7-inch round grids that come in 10, 20, 30, and 40 degrees. The smaller the number, the narrower the beam of light. The modeling light in studio strobes is invaluable when you’re using grid spots, because you can see where the light is falling. I don’t use grid spots very often with kids, but every now and then they come in handy, like when I want to create a spotlight effect. In FIGURE 5.19 you can see the effect of just a bare bulb flash with no grid spots. In FIGURE 5.20 I used a 30-degree honeycomb grid on the front of the light to concentrate the spotlight on this movie-star-in-training.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.19 A bare-bulb flash with no grid spot makes a spotlight but spills light more than I want it to.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.20 Adding a 30-degree grid spot to the front of the light narrows and concentrates the light right where I want it.

Soft honeycomb grids

Honeycomb grids (aka egg crates) are big, soft grids that you can use on big, diffused light modifiers like an Octabank or a softbox. At first, this may seem counterintuitive. Why would you use what is typically a hard-light modifier on a diffused light source? Remember that the primary use of grids is to concentrate and control the light. Used on an Octabank or softbox, the honeycomb grid actually does three things: It cuts the light by one stop, it increases the contrast, and it controls the spill of light. So, if you feel like the light from a softbox is losing its drama, just pop on a honeycomb grid; you’ll still have a big, soft light source but with an extra punch of contrast and total control of where you want the light to fall. This is especially important for me because my studio is a white box, and if I don’t control the light, it bounces everywhere, making it almost impossible to get a dark, moody look.

Subtractive Lighting

An often overlooked, yet valuable type of light modification is subtractive lighting. Subtractive lighting is somewhat of an oxymoron, but the term refers to methods used to reduce or eliminate light from reaching your subject. You can also use subtractive lighting to block light from spilling onto your background or to block light from hitting your lens if the light is aimed toward the camera.

V-flats

V-flats are also used for subtractive lighting, but in this situation the black side faces your subject. A black modifier actually reflects black onto your subject, intensifying the shadows and increasing the contrast in the image.

Gobos

Gobo (goes before/between optics) is a term used in the film industry that refers to anything used to control the shape of the light; gobos are also called flags or cutters. In the photography world, gobos are most often used for blocking a light source from striking your lens or to keep light from hitting your background. A V-flat can act as a gobo if you put it between a light and the camera. You’ll learn how to use V-flats as gobos in Chapter 7.

A Place to Start

The lighting setup I start with most of the time consists of one main light and a V-flat reflector as fill. I almost always light my background separately from my subject. Sometimes I light the background separately to create a high-key look, and other times I turn off the background lights. Either way, the setup in FIGURE 5.21 is my typical starting point. This setup creates a light sandwich with the kid as the meat in the middle. With the softbox on one side and the V-flat on the other you have a nice little pocket of light that feels like a fort to the kid being photographed. It creates a feeling of privacy and safety, in addition to reflecting the light the way I like it. I know I can get a good result from this setup, and then I can add or subtract light from there.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.21 My typical beginning setup for lighting my subjects creates a “fort” of light with a main light camera left and a V-flat camera right.

Measure

It’s been established that the quality of light is much more important than the quantity of light, but at some point you have to evaluate the results you’re getting. Is the image overexposed? Is it underexposed? You need to measure the light. Just like it took time to learn to see the light when you began photographing in natural light, it will take time to learn to see how a given studio lighting setup will look in the final image. Measuring the light with a meter can help you learn the results of a lighting setup faster. However, you first need to have a solid knowledge of some exposure basics.

When you’re shooting in natural light, you have only three exposure variables to be concerned with on your camera. The three are commonly known as the exposure triangle (FIGURE 5.22):

• ISO. Your camera sensor’s sensitivity to light

• Aperture or f-stop. How wide or small the opening in your lens is, creating depth of field

• Shutter speed. How fast or slow the shutter opens and closes, freezing or blurring action

FIGURE 5.22 The famous exposure triangle shows the relationship of ISO, aperture, and shutter speed.

Once you decide to incorporate flash into the mix, you add two additional variables to the exposure triangle, which are the two P’s of flash exposure (FIGURE 5.23):

• Power of flash. The amount of light being produced by the flash

• Proximity of flash. How close or far away your light is in relation to your subject

FIGURE 5.23 The not-so-famous exposure pentagon shows the relationship of ISO, aperture, and shutter speed plus power and proximity of flash.

Do these five variables now create an exposure pentagon? Just kidding. The easiest way for me to remember how to incorporate the two extra flash variables is to first break them down into two shooting scenarios:

• Shooting in studio. No ambient light

• Shooting on location. Using ambient light

Ambient light, also called available or existing light, is the light that exists in a scene but was not put there by the photographer. You can decide to use ambient light as part of your lighting or not. For now, let’s proceed as though you are shooting in a studio. You won’t consider the ambient light. For lighting setups that take ambient light into consideration, see Chapter 8, “Lighting on Location.”

Limit Your Variables

As mentioned earlier, when I’m photographing in the studio, the only light I want in the photo is light that I’ve put there. In other words, I don’t use any of the ambient lighting. My first task is to determine which of the five variables in the exposure pentagon (FIGURE 5.24) I can lock down immediately.

Initially, I dial in the settings that won’t change during the shoot:

1. ISO. I set the camera’s ISO to the lowest native ISO setting (usually 100 or 200 ISO) that will give me the cleanest file with the least digital noise possible.

2. Shutter speed (sync speed). I then set my shutter speed to my camera’s sync speed, which on a Nikon D4 is 1/200 of a second (sync speed was discussed in Chapter 4).

You can see by the shooting data on virtually every studio photo in this book that my ISO is at 100 and my shutter speed is 1/200 second. Two variables are locked down—check.

Now all I have to decide on is my aperture setting, or f-stop. Remember that the aperture setting will be determined by the main light’s power setting and the proximity to the subject.

Next, I shoot a picture and evaluate the exposure. If it’s not right, I’m back to just three variables to adjust:

1. Change my f-stop (wider or smaller).

2. Change the power of the light (brighter or dimmer).

3. Move the light closer or farther from the subject (brighter or dimmer).

This process is much easier to figure out in practice than it is in theory. So, go shoot something, measure the results, and then readjust your settings. That’s the only way you’ll learn how to measure your results and make good photos.

Move

The last variable to consider in the five M’s of lighting is the proximity of the light to your subject. In other words, if the light still doesn’t look the way you want it to, you may need to move it (or your subject). Where you move the light will affect the look of your image more than any other variable. You can measure and modify the light all you want, but if the light is in the wrong spot, your image still won’t look good.

The two most important factors to remember when you’re positioning a light to produce a soft, flattering look are:

• A bigger light source is better in relation to your subject.

• Move the light in close to your subject. Very, very close.

It’s All Relative

Close and far, big and small are all relative terms to describe where you place the light in relation to your subject.

As portrait photographers, you want soft, diffused light with a smooth shadow transfer. To get this look, it’s wise to use a big light source. But how big is big? Are you photographing a newborn or a 12-year-old? In relation to a newborn, a 24-inch softbox is big, but not so much for the 12-year-old. So you want a big light in relation to your subject.

Where you move the light will affect the look of your image more than any other variable.

Moving the light changes the size of the light in relation to your subject. The easiest way to make a light source bigger is to move it closer to your subject. Move the light out farther from your subject and it becomes smaller in relation to your subject.

A small 24-inch Beauty Dish can become a relatively large light source when you place it 6 inches from a toddler’s head, as in FIGURE 5.25. On the other hand, a big 60-inch Octabank can become a relatively small light source if you place it 15 feet across the room from your subject.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.25 A relatively small light source, a 24-inch Beauty Dish, becomes big when it’s brought in closer to the subject.

So when you hear that a bigger light source is best for portraits, that means a bigger light source in relation to your subject. All you need to do to make almost any light source bigger is just bring it closer to your subject, very close. At my studio we are constantly having to retouch the lights out of a shot because I work with the light in very close. In FIGURE 5.26 you can see that the Octabank is just inches from the little boy.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.26 A light source so close to the subject that the image will have to be recropped or retouched because the light was in the frame is just an occupational hazard.

If you are a natural-light shooter, the concept of bigger is better when it comes to lighting may not be foreign to you. But somehow when you make the leap into the world of flash, you might forget the lessons that your natural-light experience taught you. A common mistake when you start shooting with flash is that if the light from the flash is too bright, you think you should move the light farther away so it will be softer. But, actually, the opposite is true. The farther the light is from your subject, the smaller the light source becomes in relation to your subject, which makes the light harder. So, if the light is too bright, instead of moving it away, power down the light and keep it close to your subject.

If you power down the light as low as it will go and it’s still too bright, close down your aperture to cut the light or use a neutral density filter, but don’t move that light farther away from your subject!

When you’re considering how close or far the light should be from your subject, use this general rule of thumb: Keep the light closer than a distance of 2x the width of the modifier you are using. For example, if you are using a 60-inch Octabank, don’t place the light farther than 120 inches away from your subject. Once you approach a distance of about 2x the width of the modifier, the light looks harsh and unflattering.

Remember that closer equals softer light and farther away equals harder light. The easiest way to visualize this concept is to think of the light you’re using as a window.

Tip

If you’ve dialed your strobe light power down as it as low as it will go and it’s still putting out too much light for a wider aperture setting, try using a neutral density (ND) filter on your lens to cut the light. Variable ND filters are designed to cut the light in a scene, allowing you to shoot with wider apertures for shorter depth of field.

The Light as a Window

A vivid “aha” moment in my lighting education came at a workshop, watching the instructor set up a window-light portrait. I admired portraits lit using only the light from a window. The dimensional quality of window light seems to caress the skin of the subject. But somehow my window light portraits never looked like the shots I admired, and I couldn’t figure out why.

I watched as the instructor positioned the model with her shoulder right up against the window casing and her face just inches from the window, and there it was, the light I’d been searching for bathing her face. In an instant I saw that the closer the subject is to the light, the softer the light becomes. The reason I didn’t like my window-lit portraits was because I had been shooting with my subject too far from the actual window, which resulted in hard light. I also realized how my lighting results could differ dramatically just by changing where I placed my subjects in relation to the window—not just closer or farther from the window, but their angle in relation to the window. This made it easier to make the transition to shooting with studio flash.

In an instant I saw that the closer the subject is to the light, the softer the light becomes.

Once I made the jump to using studio flash, I incorporated my experience with window light and thought of my softboxes as windows, which made it easier to figure out where to move my lights in relation to my subject.

Imagine that an Octabank is your window. Where would you place your subject in relation to the window to get the best quality of light?

In FIGURE 5.27 I placed the boy on the back side of the light—the same place you would begin with a window light portrait. The light falling on him had some dimension; the shadow transfer was soft with no harsh shadows (FIGURE 5.28). For the next shot (FIGURE 5.29) I moved him closer to the middle of the light. Placing him at almost 90 degrees to the light created more drama with darker shadows, but the shadow transfer was still soft because he was still very close to the light. If he had turned more straight on to the camera, the effect would have shown more split light on his face, with one side in light and the other in shadow (FIGURE 5.30). When I moved him closer to the front side of the Octabank (FIGURE 5.31), I started to lose detail in the shadow side of his face because most of the light was now behind him (FIGURE 5.32).

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURES 5.27 AND 5.28 Using the Octabank like a window, I positioned my subject on the back side with most of the light in front of him. Positioning your subject on the back side of the light allows the Octabank to light the area in front, resulting in soft, flattering light.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURES 5.29 AND 5.30 By moving the boy to roughly 90 degrees to the light, most of the light is still in front of him, but he is closer to the center of the light. The 90-degree position creates more drama in the shadows, but the shadow transfer is still soft because he’s still very close to the light. This position creates a split light pattern (half in light, half in shadow) on his face.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURES 5.31 AND 5.32 Moving the boy closer to the front of the light results in most of the light being behind him. The closer the boy gets to the front of the light, the darker the shadows on his face become. The reason is that he has moved past the center of the light, and there is not enough light in front of him to illuminate his face.

Grip Equipment

Grip equipment consists of the all the gear that holds up your lights or allows you to move and keep the lights where you want them. Getting the light where you want it and keeping it there are critical. Here is a list of the essential equipment you’ll need:

• Light stands. Invest in light stands with wheels, especially for your main light (FIGURE 5.33). Movable stands allow you to move your lights quickly and easily. Light stands by companies like Avenger and Manfrotto are heavy duty, and you’ll get years of use from them. C-stands are heavy chrome stands that are great for a light that you don’t need to move. If you buy a C-stand, make sure you purchase the C-stand arm that clamps to the C-stand. This is helpful to clamp reflectors to and also allows you to use it as a short boom arm to position your light up and over your subject.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 5.33 Get a grip on your lights with the right stands and grip equipment.

• Boom arm. A boom arm mounts to your light stand and allows you to get your light up and over your subject. The bigger the modifier, the bigger the boom you’ll need. Chapter 6 discusses more about light placement.

• Sandbags. If you’re using a light on a stand, you need a sandbag to keep it from tipping over if it is bumped. You’re photographing kids and kids can get crazy, so take precautions.

• Gaffer tape. A cloth tape available in white, black, or gray, gaffer tape is like duct tape except it’s thinner and doesn’t leave a residue. And like duct tape, gaffer tape has a million uses. Use it for taping down cords to avoid tripping on them. It’s a must-have for creating V-flats. You can also use it for taping down the ends of your seamless background paper to the floor. I’ve used it for weird things too—to “hem” a child’s dress or pants, or to cover a power outlet in the floor or a light switch on a white wall, making them easier to remove later in Photoshop.

Use the five M’s the next time you have a shoot. Begin with the mood in mind, select the main light, modify the light, measure the exposure coming from the light, and then finesse and move the light until it looks the way you like it. Make it easy on yourself and start with just one light.