8. Lighting on Location

ISO 200, 1/160 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

Photography is 1 percent talent and 99 percent moving furniture.

—Arnold Newman

If you’ve been shooting primarily in natural light, then you are no stranger to shooting on location. You know how to find the light and work it. But you may have been places where the light wasn’t good, you needed more light, or just wanted to shoot children in their home but the light wasn’t ideal. Perhaps you want to create a different look, something dramatic that will wow your clients and keep them coming back. All of these are good reasons to try using flash on location.

In this chapter you’ll learn the step-by-step technique I use to quickly determine the correct exposure for creating a blink of light, a mix of flash with the light in the location, or the surreal lighting that creates dramatic skies and saturated color in your image. By applying the skills you already have and combining them with these new tactics, you’ll be lighting with confidence at your next location shoot.

Location Flash Technique

The previous few chapters focused on how to use off-camera flash in the studio. But what about lighting on location? If you’re using off-camera flash as your only light source on location, the technique is no different than the studio lighting technique you learned in Chapter 5. Recall that in the studio my exposure settings were determined by only the light that I added to the scene.

Shooting on location presents creative opportunities to add environment and context to your image; it also presents some technical challenges when it comes to lighting the environment and your subject at the same time.

The main difference between lighting in the studio and lighting on location is the complexity of using the ambient light in the scene in addition to the off-camera flash you are using to light your subject.

Mixing Flash with Ambient Light

As you learned in Chapter 5, ambient light is also called available light. Ambient light usually refers to the natural light in a scene, but if you’re working indoors, the ambient light might be created by lamps or light fixtures in the home of your client. On location, your exposure-finding process is different than in studio because instead of just worrying about the flash you are lighting your subject with, you are mixing flash with the ambient light. The technique used to mix ambient light with flash is the same whether you are working with the sun as the ambient light outdoors or household electrical lights as ambient light indoors.

The two most important factors to remember when you’re mixing flash with ambient light are:

• Aperture controls the base exposure.

• Shutter speed controls the ambient light.

The Exposure Checklist

When I’m photographing on location and want to mix my flash with the ambient light, I use the Exposure Checklist in FIGURE 8.1 as a quick reminder to help me determine my base exposure for an image. This process is explained in detail below.

FIGURE 8.1 Lock down your aperture and ISO first, and then vary your shutter speed, depending on how much ambient light you want in the scene.

The images to illustrate the Exposure Checklist were shot on a 110-degree, sunny Arizona afternoon. At five o’clock the sun was still quite high in the sky and very bright. Notice my assistant Jeff wiping sweat out of his eyes in the setup shot in FIGURE 8.2. I was lying on the 150-degree sidewalk shooting this image. You can see that there is a lot of light in the scene. How do you wrangle all that light to get a shot that looks like the image in FIGURE 8.3? The Exposure Checklist tells you how:

1. ISO. I started with my camera set to its lowest native ISO (ISO 100 on the Nikon D4). Recall that low ISOs produce the cleanest files with the least digital noise. I start at 100 and increase my ISO only if I have to (see step 6 for exceptions).

2. Proximity. Because I want soft, flattering light, I always work with my light as close as possible to my subject (Figure 8.2).

ISO 100, 1/200sec., f/11, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.2 The behind-the-scenes shot for Figure 8.3. A big light, in close, and a patch of sky are all you need.

ISO 100, 1/250 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.3 The finished shot of Super Max. Being able to light kids anytime anywhere gives you superhero-like confidence.

3. Flash power. Unless I’m shooting in extremely low or extremely bright light, I’ll start with my flash set on half power. With the Profoto AcuteB strobe, half power is 300 watt seconds. I start in the middle because I find it’s faster to adjust up or down from the middle setting.

I focus on establishing the base exposure on my subject first before I consider anything else.

4. Shutter speed. I usually start with the shutter speed at my camera’s sync speed of 1/200th of a second. If you are shooting with a dedicated speedlight, you may be able to shoot with a sync speed of 1/250, which is helpful when you want to darken the ambient light even more. I started with my shutter at 1/200.

5. Aperture. Next, I figure out what I want my aperture to be by considering the depth of field I want. For example, if I’m photographing a single child and want a very short depth of field, I’ll dial in a wide-open aperture, like f/2.8. If I’m photographing more than one child, an aperture of f/8 or smaller allows for a longer depth of field, or more of the image in focus. In this instance, I wasn’t choosing aperture for creative reasons. I chose a relatively small aperture of f/11 due to how bright it was outside, and I knew that a wider aperture would likely overexpose my subject.

6. Take a test shot. Once I have the ISO set, the light positioned, flash power, and shutter speed and aperture set, I take a test shot and see what the light looks like on my camera’s LCD screen (that’s if I’m not using a flash meter). At this point, I’m not looking at the ambient light. I’m only looking at the light falling on my subject. Is it too bright? Too dark? This is the process of establishing my base exposure. In FIGURE 8.4 you can see that the boy’s face is overexposed. He doesn’t look too happy about it either.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/11, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.4 A test shot at f/11 shows the boy’s face is overexposed.

If the light is too bright and your flash isn’t powerful enough to overpower the sun, you can shoot earlier or later in the day, when the sun is less powerful. You can also place your subject in the shade (as we did in the Exposure Checklist example).

7. Adjust. Don’t worry if the first test shot is completely wrong; it’s no big deal. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad photographer. It’s just an experiment, and the test shot is the result of that experiment. Once you see the results of the test shot, you need to make adjustments. In this instance, the exposure on the subject was too bright, so I had to decide whether to close down my aperture or decrease the flash power. I chose to close down my aperture a full stop, to f/16, which resulted in a correct exposure on my subject (FIGURE 8.5). If the exposure on the subject had been too dark, I could have either opened up the aperture or increased the power output of the flash. I work with these two variables of aperture and flash power until I have a correct base exposure on the subject. If the flash power is maxed out, the aperture is as wide as I want it to go, and the exposure on my subject is still too dark, I’ll increase the ISO setting to make the camera sensor more sensitive to light. I adjust these variables until the base exposure on the subject is correct and only then consider the ambient light. It’s easy to get distracted with all of these settings to think about, so I focus on establishing the base exposure on my subject first before I consider anything else.

ISO 100, 1/250 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.5 Closing down my aperture to f/16 provides the correct base exposure.

8. Shutter speed to mix in ambient. With the base exposure on the subject established, it’s time to look at the ambient light and determine how much I want it to factor into the image. To allow in more ambient light, I can slow the shutter speed down to 1/200, as in FIGURE 8.6, or slower to 1/125, as in FIGURE 8.7, or even slower to 1/60, as in FIGURE 8.8. Notice how the base exposure on the boy doesn’t change, but each image looks different when the shutter speed is slowed down and more ambient light is allowed to register in the image. As I incrementally slow the shutter speed, the sky becomes brighter and brighter. Remember that changing the shutter speed controls only the ambient light; it doesn’t affect the base exposure on the subject. The base exposure on the subject is controlled by the aperture setting.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.6 Keeping my aperture the same at f/16 slows down my shutter to 1/200, allowing in more ambient light and resulting in a lighter sky.

ISO 100, 1/125 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.7 Slowing down the shutter to 1/125 creates an even lighter sky, but the base exposure on the boy remains the same.

ISO 100, 1/60 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.8 With a shutter speed of 1/60, the sky in the background is lighter still. The base exposure on the boy doesn’t change.

Location Lighting Styles

You can apply the aforementioned technique for mixing ambient light with flash on location in three distinct ways: using barely a blink of light to fill in shadows, mixing it up with indoor lighting, and adding the surreal look of dramatic skies in a landscape. The ability to mix ambient light with flash in each of these three ways is a significant skill set to add to your lighting toolbox.

Barely a Blink

Sometimes the light on location is just right, and all you need is a blink of light to clean up distracting shadows. In FIGURE 8.9, the sun was high at about 11 a.m. and was casting some harsh shadows on the boys’ faces. I thought I might be able to shoot with no flash and establish my base exposure at f/16 at 1/200. Placing a flash at three-quarter power (400 ws) camera left was just powerful enough to clean up the shadows (FIGURE 8.10) and even out the exposure. Notice that the exposure was the same in both images, with and without the light. The reason is that the main light was firing at the exact exposure of the sun. This is a subtle mix of ambient light and flash. Because the exposure of the sun and flash were equal, you almost can’t tell the flash is there. The resulting image looks like it was lit with natural light, but better.

ISO 200, 1/200 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens, No flash

FIGURE 8.9 The marine layer (slightly overcast) near the beach provided rich blue skies and saturated color in the scene. But at 11 a.m. the almost-overhead angle of the sun created harsh shadows on the boys, especially on the eyes of the boy wearing the hat.

ISO 200, 1/200 sec., f/16, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.10 The Photek Softlighter Umbrella positioned camera left created a big, diffused fill flash that complemented the good light already in the scene. I didn’t need to completely change the light in the setting; I just needed to correct the light by lifting the shadows on my subjects’ faces.

Mix It Up

Before I started using flash in my location work, I’d often arrive at a location and find a perfect room or setting, only to realize that there wasn’t enough light to create a decent image. Sure, I could have cranked my ISO through the ceiling, but the resulting image would be noisy and degraded. Bringing a lighting rig with me gives me the freedom to make any setting work.

The kids in FIGURE 8.11 had decided to put on a show using the kitchen counter as their stage. Their parents had recently built a beautiful home, and I wanted to show it off, but there wasn’t enough light in the kitchen to properly capture the kids’ antics. With the Photek Softlighter on a strobe head positioned camera right and my California Sunbounce 4–by-6-foot reflector camera left, I created a sandwich of light that allowed the kids to dance and sing and be well lit. After I established my base exposure at f/8, I dialed down my shutter speed to 1/125 to allow some of the ambient light from the kitchen light fixtures to bleed into the image. Slowing down my shutter even more would have allowed more of the room light to register, but these kids were really moving, and because I didn’t want any motion blur, I kept my shutter at 1/125.

ISO 100, 1/125 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.11 At an aperture of f/8, the background wasn’t thrown out of focus, which could have competed with my subjects. I dialed down my shutter speed just enough to let in a little light from the light fixtures, which kept the background darker and let the separately lit kids pop.

Surreal Skies

Annie Leibovitz popularized the Surreal Skies look when she shot the American Express campaign back in the 90s. She lit celebrities by flash and used deep and dramatic skies as background; there was no doubt that the lighting had been manipulated.

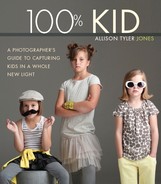

When shooting for a surrealistic look, I light the subject and the background separately for a dramatic effect. In FIGURE 8.12, the light in the form of flash is the primary illumination on the subjects; the ambient light, the sunset, provides the light for the background. The light in the scene has obviously been dramatically wrangled into submission, creating rich, saturated color and dramatic skies. This is my favorite use of location lighting, and it isn’t that difficult to achieve.

ISO 200, 1/160 sec., f/5.6, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.12 Two brothers ham it up on the beach in front of a surreal sunset. When shooting on a windy beach with a big light modifier, it is wise to have an assistant or parent hold the light.

Bringing a lighting rig with me gives me the freedom to make any setting work.

The Exposure Checklist provided earlier in this chapter outlines the step-by-step method for establishing a base exposure on your subject and creating darker or lighter skies in the background. The same method was used for the image in Figure 8.12. The sun was setting and the light was getting low, so I set my ISO at 200 and opened up my aperture to f/5.6. I then slowed down my shutter speed to 1/160 to allow more of the ambient light in the background to register in the scene. I love how the warm sunlight reflecting off the water and wet sand contrasts with the cool blue of the sky.

FIGURE 8.13 shows the same boys in the same setting lit only by natural light. This isn’t an either/or situation; it’s not that one image is bad or the other good. Both lighting techniques are simply options to choose from—tools you can use to create the look you’re after. Using the Exposure Checklist as your guide, try out this technique on your next location shoot. You, and your clients, will love the way it looks.

ISO 500, 1/160 sec., f/2.8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.13 Here is another shot of the same brothers on the same beach—this time using only natural light.

Studio or Location?

One of the first questions my clients ask when they call to book a session is, “Where should we do the session?” The consultation with the parents, mentioned in Chapter 2, is when we make the decision about where to shoot. During the consultation I make it a point to find out what types of images the clients already have of their children. If they have lots of location images hanging on their walls, I suggest that maybe a studio shoot would be a nice change. If they’ve had their children photographed mostly in studio, I suggest shooting on location.

If you shoot in the clients’ home, you can get a studio look and location setting all in the same shoot.

During the consultation I focus on the end product: What we are shooting for? What are their plans for what we’ll create with these images once they are captured? If we are creating an album with a clean, graphic design, I prefer to shoot in studio on seamless so I can easily extend backgrounds. On the other hand, if we are creating a Day in the Life album, which requires more of a storytelling approach showing the children engaged in their daily activities, shooting on location is the obvious choice. I alternate between studio and location shooting, depending on what the kids are doing and what stage they are at in their life.

If you don’t have a studio, don’t worry. When I refer to “in studio,” I’m simply referring to a studio lighting setup, which you can set up anywhere. If you shoot in the clients’ home, you can get a studio look and location setting all in the same shoot.

My favorite times to photograph kids on location are when they are newborns, when I’m shooting kids with their families, and when I’m creating images for a Day in the Life album. For all of these types of sessions I plan on shooting with natural light and flash lighting. The plan to shoot both ways gives me variety in my images and complete control over the lighting in the environment.

Tip

Shooting on location with lighting is a big job for one person to handle. Consider hiring an assistant. You will be more relaxed and able to concentrate on the client if you have some help.

Newborns at Home

My favorite place to photograph newborns is in their home, because new moms feel more comfortable. They have everything they need right there, and I like the idea of adding context to the images by using the family’s natural environment as background. Newborns alone are not that interesting to me; what is interesting is the change in the family structure brought about by the arrival of a new person.

Always keep your eyes open for areas of good light.

Because most families will move multiple times during a child’s life, it’s an important memory for them to have photographs of their baby in the home they lived in when the baby was born. It also gives you a chance to document all the hard work that went into that baby nursery.

Tip

Don’t overlook bathrooms for great lighting opportunities. Frosted or glass block windows combined with white, reflective tile surfaces create a white box that is an ideal spot to look for great light.

During a location newborn shoot, I’ll capture a variety of natural-light and flash-lighting images. Even if I’m using flash lighting, I still try to make it appear as though the image was lit with natural lighting, such as in the FIGURE 8.14 image of the twins on their parents’ bed. The room was very dark so I shot with a Photek Softlighter Umbrella from the side while I stood over the two swaddled babies. I shot the exposure in this image just like I would a studio image, not taking into account any ambient lighting and exposing only for the flash.

ISO 400, 1/200 sec., f/10, 24–70mm lens

FIGURE 8.14 As I stood on a bench at the foot of the parents’ bed to get up and over the babies, I shot this image using a strobe head inside a Photek Softlighter Umbrella positioned to one side.

The beauty of photographing newborns at home is that, because babies are small, you need to find only small areas of good light or interesting backgrounds. Big vistas of amazing-ness are not required for beautiful images. For example, the shot in FIGURE 8.15 was “discovered” as we were wrapping up a newborn shoot. As we were packing up to leave, I walked by a guest bathroom and saw beautiful light coming from the doorway with the cat asleep on the bathmat in front of a frosted French door to the backyard. We swaddled the baby again and placed her on the bathmat, bathing her in gorgeous, natural light that also helped show her reflection in the marble floor in front of her—pure location lighting luck.

ISO 200, 1/250 sec., f/2.8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.15 Always keep your eyes open for areas of good light. Here I exposed for the baby, allowing the highlight from the backlit door to overexpose, or “blow out.”

Family on Location

When I photograph kids with their family on location, I prefer that the location mean something to the family. The shoot might take place at their home, at a location that has some significance for them, somewhere they often spend time together, or a place that symbolizes something about their family, such as a lake setting for a family who enjoys water sports or a house of worship for a deeply religious family.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of the common photography spot. Some locations around my town have become notorious for their popularity with local photographers. In one large subdivision is an enormous rock waterfall. It seems like an ideal place to photograph a family until you get there and see ten photographers lined up with their clients waiting to be photographed in front of it. When any of my clients suggest this location to me, I gently steer them toward a location that has more integrity and meaning for their family.

Tip

If you need to “turn down the sun,” try using a variable neutral density (ND) filter on your lens. Variable ND filters act like a dimmer switch for your lens, allowing you to use a more powerful (bright) light source and still get a shallow depth of field on your subject. A good ND filter isn’t cheap, so buy one ND filter the size of your largest lens and then purchase step down rings to use it on your smaller lenses.

A favorite client of mine had a specific location in mind: A new LDS Temple was being built close to her home and she wanted a photo of her family in the field in front of it. I scouted out the requested location beforehand and confirmed that the alfalfa field across the street from the temple would provide an uninterrupted view of the temple behind the family. The temple was still under construction so I knew we’d be retouching out cranes and construction trailers. I shot some scouting images to determine the best angle to shoot from.

We lucked out on the day of the shoot. Gorgeous clouds filled the sky (a rare occurrence in the desert). A couple of shooting problems usually accompany beautiful, cloudy skies; one of which is wind. The combination of wind and clouds means that your exposure will constantly change as the clouds move across the sun. That and the fact that when you’re shooting with a large light modifier like the Photek Softlighter, it becomes a sail for your light. Therefore, it’s helpful to have an assistant hang on to the light and keep it where you want it.

An alternate way to determine your base exposure is to start by metering the sky with your in-camera meter. With the camera on Auto, fill the frame with the sky, press the shutter release halfway, and read the meter in your camera. Switch your camera to manual mode and dial in the metered exposure settings to lock in the exposure. For FIGURE 8.16 the meter reading for the sky was f/8. You can see from my test shot that without flash my subjects are backlit and dark.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.16 The before shot, where I metered for the background and used the kids as an outline.

I knew with the sky that bright that I’d need my flash to be close to full power to expose my subjects correctly. So I added a strobe flash with the Photek Softlighter camera left with the flash power set at three-quarter power (400 ws). FIGURE 8.17 shows the family exposed correctly with a dramatic sky as a background.

ISO 100, 1/200 sec., f/8, 70–200mm lens

FIGURE 8.17 The family photographed in a field in front of an LDS Temple.

As the sun set, the ambient light became darker, so I had to open up my shutter more to allow the decreasing ambient light to register in the image. The image in FIGURE 8.18 was shot after the sun had set, but some ambient light was still in the sky. I had to increase my ISO to 200 and open up my aperture to f/5.6; slowing my shutter speed to 1/125 allowed what little light was left in the sky to register in the image.

A Day in the Life

Children in the four-to-ten-year-old age range—preschoolers through school age—are my preferred candidates for a Day in the Life series that documents them in their home environment. The two brothers in FIGURE 8.19 are two of my favorite kids to photograph. They’ll do anything, and they do it with style. Here, they were trying out their latest tricks on their backyard half pipe. I had been shooting in natural light at f/4 at ISO 200 with a shutter speed of 1/125 of a second, but the sky was blown-out white and I just wasn’t getting the color saturation or drama I wanted in the shot.

ISO 200, 1/200 sec., f/8, 24–70mm lens

FIGURE 8.19 Natural light was just not cutting it for the energetic vibe I was getting from these two brothers. I turned their backs to the sun, leaving their faces in shadow, and lit them with the Photek Softlighter and Profoto Acute B strobe at full power (600 ws). The shutter at sync speed gave me the dark blue sky.

I had my assistant grab the light and climb up on the half pipe with me, and let the boys do their thing with minimal direction. It was late afternoon but still pretty bright because the sun was facing us directly. I powered the flash to max power (600 ws) and shot with my shutter at 1/200 of a second to get the sky as dark as possible and also to freeze the boys’ action. The resulting exposure was too bright on the boys so I closed down my aperture to f/8 for a correct base exposure. Once I liked how everything looked, I let the sun flare in the lower right of my lens, which added to the energy of the image (Figure 8.19).

Two sisters in princess dresses wanted a shot together in their newly decorated, shared room. Jumping on the bed developed into a pillow fight with the photographer. Notice that the lamp between the beds provides a nice warm glow in the background because my shutter was set at 1/100 of a second, which allowed the ambient light from the lamp to register in the image (FIGURE 8.20). The main light was provided by a strobe in a Photek Softlighter Umbrella at camera left.

ISO 200, 1/100 sec., f/5.6, 24–70mm lens

FIGURE 8.20 The two girls in their bedroom are engaged in a pillow fight with the photographer.

When you bring your light with you and know how to use it, the world becomes your studio.

Better in Studio

My preference is to photograph older babies and toddlers in the studio because it’s a more controlled environment. I like to focus intently on capturing every eyelash and chubby body. I don’t advise chasing toddlers around a park; there’s just too much for them to be distracted by. If you’re shooting outside, typically you’re trying to get that golden hour of light and young kids tend to be tired and irritable at that time of day. I used to call the hours between 5 p.m. and bedtime the “witching hour” at my house because my kids were cranky and unreasonable. It might be the golden hour for light, but there’s nothing golden about most kids’ behavior at this time of day; I’d rather photograph well-rested little ones in the morning in studio.

When you bring your light with you and know how to use it, the world becomes your studio. Regardless of where you’re shooting, a solid foundation of location lighting techniques will give you the confidence that you can make it happen.